Seljuk architecture

The beginning of the Seljuk rule in the 11th century marks a historic turning point in Islamic civilization. Arab culture had shaped the Islamic world since the Islamic expansion . The Seljuks dynasty established the political and cultural domination of Turkic peoples . The architecture of the Greater Seljuk rulers in Persia and their vassals, the Sultans of Rum , shaped an epoch of Persian architecture as well as the Islamic architecture of Asia Minor. The Seljuk building design remained a stylistic model for early Ottoman architecture until the 15th century .

Historical background

As part of the tribal union of the Oghusen , the Seljuks belonged to the Turkic peoples who immigrated to Transoxania in the 8th century . Among their leaders Tughril and Tschaghri Beg the Seljuk Turks conquered 1,034 Khurasan and defeated in 1040 in the battle of dandanaqan the Ghaznavids . With the conquest of Baghdad in 1055, Tughrul ended the protective rule of the Bujids over the Abbasid caliphate . Tughrul Beg subjugated large parts of Persia and, in 1055, Iraq . He moved the capital of the Seljuk Empire to Rey near what is now Tehran .

After the victory over the Byzantine Empire in the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the Seljuk Sultan Alp Arslan extended his rule in the west. 1077/8 Sultan Malik Şah I. appointed Suleiman ibn Kutalmiş as governor of the new province of Anatolia. Their capital became Nikaia . After the conquest of Antioch in 1086, Suleiman declared himself independent, but was defeated and executed by Tutusch I , the brother of Malik Şah. In the course of the immigration of large numbers of nomadic Turkmens , independent emirates emerged in Anatolia, including the Danischmenden who ruled the region around Sivas , Kayseri and Malatya between approx. 1092 and 1178 , the Saltukids (1092–1202) around Erzurum , the Ortoqids (1098– 1234) to Dunaysir , Mardin and Diyarbakır , and the Mengücek (1118–1252) to Erzincan and Divriği . The emirates of the Danischmenden and Saltukids later merged into the Sultanate of the Rum Seljuks , the Ortoqid rule ended with the conquest by the Egyptian Ayyubids , the rule of the Mengücek only ended with the fall of the Seljuq rule in the Mongol storm .

In the Battle of the Köse Dağ, the Seljuks of Rum were defeated by the Mongols in 1243 and had to recognize the supremacy of the Ilkhan . At the end of the 13th century the governor of the Ilkhan in Anatolia, Sülemiş, revolted against Ghazan Ilkhan . The weakness of the Byzantine Empire in the west and the Ilkhanid Empire in the east offered the Turkic Beys the opportunity to establish their own smaller rulers. The Beyliks emerged , among which the Beyliks of Aydın (1313–1425) around Ephesus , Saruhan (1300–1410) around Manisa , and above all the Beyliks of Osman I , from which the Ottoman Empire should emerge from 1299 within a short time , achieved architectural historical importance.

Architecture of the Great Seljuks

Within two to three generations, the way of life of at least the Seljuk elite had changed radically: Originally, the nomadic steppe dwellers lived in yurts , the traditional Central Asian living tent. After the conquest of Iran and Mesopotamia, they took over the government and administrative structures of their predecessors. In the field of architecture, the Seljuk architects developed an independent design language: They succeeded in combining well-known building elements such as the central building with dome or ivane coherently and harmoniously.

role models

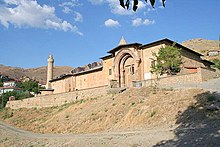

The architecture of the Seljuks takes on models from the architecture of the Karakhanids and Ghaznavids : Central buildings like the later Seljuk building types can already be found in Karakhanid architecture. The Deggaron Mosque from the 11th century in the small town of Chasar near Bukhara is made of clay and brick bricks. Its 6.5 m wide dome rests with four pointed arches on only 30 cm wide, low columns. There are smaller, 3.6 m diameter side domes above each corner of the hall. An important example of a domed central building is the Talchatan Baba Mosque, about 30 km from Merw . The building from the 11th or 12th century, made entirely of bricks, measures 18 x 10 m. It has a central dome; At the side the room is enlarged by smaller cross vaults. The facade is structured with niches, the facade is decorated with different types of bricks.

The Ghaznawid palace complex in Leşker-i Bāzār in southern Afghanistan was excavated by Schlumberger in 1948 . The south palace measures 164 x 92 m. The walls are made of mud bricks on brick foundations. It has a 63 x 45 m courtyard with four ivans. Other small side courtyards are also designed according to the four-iwan scheme. The foundations of a mosque were excavated on the south facade of the palace complex in 1951. This had two side halls with two rows of columns to the north and south of a central section, the massive rectangular brick pillars of which were very likely to have supported a dome. The front of the building was open.

Individual components

Seljuk architecture uses the same or similar structural elements for different buildings. Mosques, caravanserais, madrasas and tombs can be built as a hall or central building with or without a dome, courtyard, riwaq arcades, ivans or minarets. Viewed individually, the individual components are derived from, in some cases, much older models. The architectural-historical achievement of the Seljuk architects, who are nameless with a few exceptions, consists in the synthesis of these elements into uniform and architecturally coherent, style-typical buildings.

Dome and vault shapes

The system of corner trumpets was already known in Sassanid times , by means of which a round cupola can be placed on a rectangular base . The construction of bricks , which were laid in a relatively thick layer of mortar, allowed the dome to be built freely without the use of falsework . The spherical triangles of the trumpets were split up into further sub-units or into niche systems. This resulted in a complex interplay of supports and struts, ultimately an ornamental spatial pattern made up of small-scale elements that optically cancel out the heaviness of the building.

Typical of the Islamic East was the non-radial rib vault , a system of intersecting pairs of vaulted ribs covered by a crown dome. Starting from the Friday Mosque of Isfahan, this arch shape allows the ostislamischen architecture until the Safavid period based tracking of key buildings. The main features of this type of vault are:

- A type-defining square of intersecting vault ribs, sometimes formed into an octagonal star by doubling and twisting;

- the elimination of a transition zone between the vault and the support system;

- a crown dome or lantern riding on the rib structure .

In Seljuk architecture, the intersecting pairs of ribs still form the main element of the building decor.

Trumpet dome of the Suleymaniye Mosque, Alanya

Isfahan Friday Mosque , interior view of the north dome

Minarets

The Iranian Great Seljuks most often used the slim, cylindrical shape of the minaret . The oldest surviving manar from the Seljuk period is that of the Tārichāne mosque in Damghan from the time of Tughrul Beg (1058). It is also the first Seljuk construction to be known to use glazed bricks. The staggered arrangement of the bricks in the tower wall creates an impressive decorative effect. The similarly designed minaret of the Masjid-i Maidan in Saveh is dated by Aslanapa to the time of Alp Arslan (1061). Other Seljuk minarets can be found in the Friday mosques of Kashan and Barsiyan near Isfahan. For the first time, facades were also equipped with two uniform minarets.

Mosques

Major Seljuk mosques were built between around 1080 and 1160. The Seljuk architects developed a monumental type of building from the classical Islamic hall mosque, which consists of a hall with a wide dome arching over the mihrab niche . The classic design of the of Riwaq lined -Arkaden court ( Sahn ) was constructed by inserting four Iwanen expanded. In all buildings there is a domed hall with an ivan in the center. On the longitudinal and transverse axis of a cross-shaped floor plan, two ivans face each other in the middle of the rows of riwaqs on each side of the courtyard. The four-iwan plan has shaped the design of Iranian mosques and madrasas up to the modern age.

Isfahan Friday Mosque

The Friday Mosque of Isfahan is the oldest surviving mosque in the Seljuk period. The original building was built under the Abbasid caliph al-Mansūr (r. 754–775) as a classic courtyard mosque made of adobe bricks . Sultan Malik Şah I (ruled 1072-1092) had the building restored and expanded. According to the building inscriptions, the large mihrab dome and the smaller, also domed north hall were built under Malik Şah. The Seljuk Grand Vizier Nizam al-Mulk and his rival Taj al-Mulk erected two domed buildings along the longitudinal axis of the courtyard around 1080. The dome of Nizam rests on eight heavy, stucco-covered pillars, which probably come from an earlier construction phase, and opens on three sides with nine arches towards the prayer hall. A few decades later, the hall's beamed ceiling was replaced by hundreds of domes. In a third construction phase, four ivans were created in the center of the façade of the inner courtyard. In Seljuk and Timurid times, courtyard fronts and the inside of the ivans were covered with glazed tiles. The geometric , calligraphic and floral ornamentation disguises and hides the structural shape caused by the load distribution of the building. This established an architectural tradition that set the style for the buildings of the Islamic East of the subsequent period.

Great mosques of Qazvin and Zavareh

Later Seljuk mosques were built based on the model of Malik Şahs I in Isfahan. Here too, older hall mosques from the Abbasid period were often revised. The Friday Mosque of Qazvin (erected in 1113 or 1119) has a dome that rests on simple, but monumental-looking trumpets and strong brick walls. A calligraphic inscription in Naschī script running around the trumpet arches shows that the builder was Muhammad I. Tapar , the son of Malik Şah.

The Friday mosque of Zavareh in the province of Isfahan (1135) combines in its building design all innovations of Greater Seljuk architecture: It has a 7.5 m wide mihrab dome, four ivans and a minaret. Here the four-iwan plan is implemented for the first time in a Seljuk mosque. The staggered arrangement of the bricks creates geometric patterns in the area of the trumpets and in the dome itself.

Great Mosque of Ardestan

Following the example of the Friday mosque of Zavareh, numerous other Seljuk four-ivan mosques were built, including that of Ardestan (1158), only 15 km away from Zavareh. In this case, the upper part of the brick walls is again surrounded by a calligraphic inscription in Thuluth script . Above it are the trumpets and the 9.30 m diameter mihrab dome, which looks similar to that of Taj al-Mulk in the Friday mosque in Isfahan. The design of the trumpets, which lead from the square substructure to the dome, is one of the masterpieces of Seljuk dome construction. Here, too, staggered bricks form a pattern in the masonry. In contrast to other Seljuk buildings, the inner surfaces of the arches between the pillars are covered with stucco and decorated with calligraphic inscriptions and stucco ornaments. In contrast to the rich interior decor, the exterior walls form a system of massive brick cubes without any decoration. On a square base, slightly set off by an octagonal transition zone, the dome tapers towards the top. In this mosque, the northern ivan is much more monumental than the actually more important ivan in the qibla direction. This, on the other hand, is highlighted by two lower, two-story side cabins and two minarets.

Madrasas

Only a few examples of this important type of building are known and preserved from the Greater Seljuk period. In 1046, Tughrul Beg established a madrasa in Nishapur . From the time Malik SAHS I. originated Heydarieh-Madrasa in Qazvin . It has a domed hall with simple trumpets and strong brick walls. With wide arches, the upper sections of which are completely covered by a monumental Kufic inscription, it opens on three sides. The Seljuk vizier Nizām al-Mulk (1018-1092) had some important madrasas built, which are known as Nizāmīya (al-Madrasa al-Niẓāmīya ) to spread his Shafiite school of law ( madhhab ) : 1067 in Baghdad, further among others in Nishapur and Tūs in his place of birth . Only two Iranian Nizamiyye madrasas are known and have been archaeologically researched, in Chargird (1087) and in Rey . From the archaeological evidence, however, it only appears that the buildings could have owned Iwane.

Caravanserais

The caravan trade by land required safe accommodation for people, animals and goods every day. In the Karakhanid period (8th – 9th centuries ) the caravanserai developed from the type of Arab border fortress ( Ribat ) . In Ribat-i Sherif, a representative caravanserai in the north-eastern Iranian Khorasan , a narrow gate first leads into an arcade-lined entrance courtyard. This is separated from a second, longer inner courtyard by a continuous wall with a narrow passage. This has a central water basin and a richly ornamented, higher main divan. The inner facades of the courtyard are decorated with ornaments made of staggered brick. The courtyards are surrounded by individual rooms, each of which opens onto the inner courtyard. The main rooms, for example behind the north divan, are domed.

Grave structures

Seljuk tombs ( Turkish turbe or kumbet ) follow the building tradition of the Arab-Islamic, mostly free-standing tomb, the Qubba . Burial towers with domed or conical roofs ( Gonbad ) are also known in traditional Persian architecture . The Gonbad-e Qabus , built in the first years of the 11th century by the Ziyarid ruler Qabus (r. 978–981 and 987–1012) in the northern Iranian province of Golestan, can serve as a model .

The tower-like central structures of the grave architecture have a polygonal symmetrical base and a slim, semicircular , pyramidal or conical roof. The inner transition to the dome in the Seljuk tomb towers is made by rows of keel arches placed one on top of the other. The tombs of the founders of religious buildings were often integrated into their buildings. Well-known tombs of Great Seljuk architecture are the Charaghan tomb towers in the province of Qazvin between the northern Iranian cities of Qazvin and Hamadan , from the 11th century.

Architecture of the Anatolian Seljuks

The Seljuks were the first Islamic rulers in Asia Minor . They first introduced elements of Islamic architecture in Anatolia. They took over the construction method developed by the Great Seljuks in Iran, but did not use brick and mortar, but house stones . Only higher building components were built using brick. Significant Seljuk buildings are still preserved in the former capital Konya , as well as in the cities of Alanya , Erzurum , Kayseri and Sivas .

Deviating from the architecture of the Persian Great Seljuks, the Rum-Seljuk architecture in Anatolia has taken its own path in that it is more oriented towards Syrian architectural styles: Architecturally significant building elements such as the large portals are often built from alternating light and dark stone blocks. These as Ablaq ( Arabic أبلق, DMG ʿablaq ' multicolored, literally piebald') well-known wall type characterizes the Syrian architecture of the 12th century. In 1109, repair work was carried out on the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus using Ablaq-style masonry. Its dome was rebuilt at the end of the 11th century by Malik Şah I, who also redesigned the Great Mosque of Diyarbakır. According to Aslanapa, the name of one of the builders of the Alâeddin Mosque of Konya , Muḥammad Ḥawlan al-Dimishqī ("the Damascene"), mentioned in inscriptions , suggests that he might have brought this style from Syria, which was then ruled by the Zengids , to Konya. Syrian architect built for Kılıç Arslan II and Kai Kaus I. the fortifications of. Antalya , Alanya and Sinop , and the Sultanhanı - Caravanserai in Aksaray .

Epoch of the Seljuk Emirates

|

|

|

|

Left picture : Isabey Mosque in Selçuk , Izmir Province.

Right picture : Floor plan of the Isabey Mosque |

||

The first known Great Mosque , built in Anatolia, was the 1091 Seljuk Rum by Sultan Malik Shah built Great Mosque of Diyarbakir . Under the Seljuk sultans Kai Kaus I (1210 / 11–1219) and Kai Kobad I (1220–1237), Seljuk architecture in Anatolia reached its "classical period". Numerous religious foundations ( Waqf ) were set up to finance building complexes. These consisted mostly of a mosque or a madrasah , often connected to a bath ( hammam ), kitchens ( imaret ) or a hospital. The flourishing trade called for permanent and safe accommodation ( caravanserais ) along the trade routes.

Early mosque buildings

Great Seljuk architecture had developed a structure that was to set the style for later Ottoman architecture : the mosque with a main dome over the mihrab niche. One of the first mosques of this type was the Friday Mosque of Siirt , which was built in 1129 under Mughīth al-Dīn Mahmud , a sultan from the Great Seljuq dynasty . He ruled from 1119 to 1131 as a vassal of the supreme sultan Sanjar of Western Iran and Iraq . The Great Mosque of Siirt thus represents a link to the architecture of the Iranian Great Seljuks. The original building had a dome that rested on trumpets and was supported by four brick pillars. Later, secondary domes and an ivan with two vertical vaults were added on the east and west sides. The crooked minaret, now a symbol of the city, is reminiscent of the brick minaret of the Great Mosque of Mosul , although the minaret in Siirt is simpler and more archaic.

The Great Mosque of Dunaysir , today Kızıltepe in the province of Mardin in southeastern Anatolia , is a major work of Ortoqid architecture. Similar to Diyarbakır, two-story riwaqs once enclosed an inner courtyard (Sahn) on three sides. The facade of the prayer hall featured richly decorated portals and outer mihrab niches. The three naves of the prayer hall are vaulted with barrel vaults. A dome about 10 m in diameter rose above the inner mihrab niche and crossed two naves. The prayer niche is flanked by two pillars with muqarnas capitals. It has the shape of a shell under a seven-pass arch and is decorated with deeply carved reliefs. The construction plan of this mosque also follows that of the Umayyad mosque.

The Great Mosque of Harput , built by the ortoqid emir Fahrettin Karaslan between 1156 and 1157, has only a very small inner courtyard, which is three arches long and two arches wide. It is lined with two-aisled riwaqs and adjoins a three-aisled prayer hall. In the Koluk Mosque in Kayseri , one establishing the Danishmends from the second half of the 12th century, the Sahn is reduced to the width of a single sheet which is surmounted by a dome. Under this is a water basin.

Great Mosque of Divriği

Divriği, the capital of the Mengücek, is known for its Great Mosque and the adjoining hospital (darüşşifa) . The mosque was built by Ahmetschah in 1228, the hospital in the same year by Turan Melek Sultan, daughter of the ruler of Erzincan , Fahreddin Behramschah. The 63 x 32 m large rectangular building extends in a north-south direction. In the south, the hospital takes up about a third of the floor space, its only entrance is on the west side. The north wall of the hospital is also the qibla wall of the mosque. Its prayer hall is divided into five naves by four rows of pillars, with the central nave being significantly wider than the two aisles. From the main entrance in the north, the view falls through the middle row of pillars onto the central mihrab . The second entrance leads from the west wall into the space between the middle pair of pillars. The hospital, which is attached to the pillar hall of the mosque, is a closed domed building with four cross-shaped ivans around the central hall. The walls are made of stone blocks of the same size, about 40 cm high and 40–100 cm long. Both buildings are a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Turkey .

Madrasas of the Seljuk emirs

One of the oldest madrasas from the time of the Seljuk Emirates is the Yağıbasan madrasah in Tokat : built in 1151–57 by the Danish Menden emir Yağıbasan, it has two ivans on an asymmetrical floor plan that open onto an inner courtyard with a trumpet dome. The masonry consists of raw rubble stones and has no further decoration in its current state. The Masʿudiyya madrasah (1198–1223} on the north arcade of the Great Mosque of Diyarbakır was built by the architect Jafar Ibn Muhammad from Aleppo under the Ortuqid Emir Qutb ad-Din Sökmen (II.) Ibn Muhammad. Two-storey arcades on three sides of the courtyard form a cross-axis floor plan that is oriented towards the north portal. An example of a medrese / Darüşşifa with an open inner courtyard can be found in the single-storey foundation building of Kai Kaus I , the Şifaiye Medrese in Sivas (1217–18) The stone building has a rectangular courtyard lined only on the long sides by arcades with only one large ivan opposite the main portal. An axis of the cross is emphasized by further arcades. On the right side of the courtyard is the brick doorway of the Emir, who died in 1219.

Mosque construction of the Rum Seljuks

One of the oldest Seljuk mosques in Anatolia is the Alâeddin Mosque of Konya , begun around 1150 by Rukn ad-Dīn Mas'ūd and completed in 1219 by ʿAlāʾ ad-Dīn Kai-Qubād I. The architectural design is still based strongly on the Arab hall mosque , the central section of the prayer hall with a mihrab dome corresponds more to the Anatolian building tradition. The floor plan is irregular, two tombs in the inner courtyard have not yet been fully integrated into the building, as was customary later. The pillars of the prayer hall, which is flat with wooden beams, are ancient spoils. The courtyard is surrounded by walls that only have narrow, open pointed arches on rather clumsy pillars in the upper quarter of the representative north facade; There are wider pointed arch niches above the portals.

The last mosque built by the Rum Seljuks in Konya is the Sahip-Ata Mosque (1258). Its main portal (tac kapı) has a filigree muqarnas decor. The facade is decorated with staggered, partly blue glazed bricks, which reproduce the names of the caliphs Abū Bakr and ʿAlī in monumental square Kufi script.

The Eşrefoğlu Mosque in Beyşehir is a mosque built in the late period, and at the same time one of the few remaining mosques from the Seljuk period with wooden pillars and wooden roofs , the interior decoration of which with faience tiles is one of the masterpieces of the Seljuk style of Islamic ceramics .

Madrasah

The madrasas in Asia Minor from Rum-Seljuk times are mostly smaller than the Persian ones. Often the tomb of the builder is integrated into the complex. In addition to buildings with a central dome, there are also those with a rectangular inner courtyard ( avlu ) and a single large ivan opposite the entrance. The Seljuk madrasas were proposed for inclusion in the UNESCO World Heritage List on April 15, 2014.

Madrasa in Erzurum

Two important Seljuk madrasahs, the Çifte Minareli madrasah (around 1230–1270) and the Yakutiye madrasah (1310/11), are located in the city center of Erzurum. One of the original two typical Seljuk brick minarets is still preserved. Detailed building descriptions can be found in the article on the city of Erzurum .

Madrasas in Konya and Sivas

In the Sırçalı (“mosaic”) medrese in Konya from 1242, the roughly square iwan on the southern rear wall has a prayer niche and side domes. There is a water basin in the center of the courtyard. The small grave room of their founder Bedreddin Muslih is on the west side of the large entrance portal in the east.

In the Ince Minareli Medrese ("Medrese with the thin minaret"; 1260–65) in Konya , the entrance gate is so enlarged that it takes up almost the entire facade. Calligraphy in Thuluth script reproduces the first 13 verses of the 36th sura of the Koran , Ya-Sin , as well as the sura al-Fātiha . The inscription on the top rosette relief of the entrance gate also mentions the name of the architect in Kufic script: Kelük bin-Abdullah. The inner courtyard of the madrasah is domed, the inside of the dome is lined with dark purple and turquoise tiles. An inscription runs around the base of the dome: " Il-mülkü l'illah - God's property".

Like the Ince Minareli, the Gök (“Blue”) madrasah in Sivas is a foundation of the Rum-Seljuk Grand Vizier Sahip Ata (d. 1288/1289). Originally the building was laid out on two floors, only the lower floor has been preserved. The building complex ( külliye ) had a hammam and a kitchen ( İmaret ) . The 31.5 m wide building with a 24.3 x 14.4 m measuring inner courtyard in the classic four-ivan scheme has, like most of Sahip Ata's buildings, two minarets, here 25 m high, on both sides of the typically Seljuk entrance portal. Unusual for Seljuk architecture are the two unequally wide domes in the inner courtyard behind the entrance facade, which are not visible from the outside and covered with blue glazed tiles. The walls of the madrasah are made of limestone, the doors and minarets are made of bricks; the main portal is complete, individual details such as the capitals of the columns are made of marble. The smaller Buruciye Medrese in Sivas (1271) has a more symmetrical four-iwan construction plan than the Gök Medrese.

Caravanserais

At the moment about 200 Seljuk caravanserais are known, of which about 100 have been preserved in various states. In the architecture of the Anatolian Hans or caravanserais, three types can be distinguished: A simple walled courtyard, as in Evdir Han (1215), a simple columned hall as in Ciftlik Han, or a hall with an upstream courtyard, such as in Alayhan near Aksaray , im Kırkgöz Han (1237–1246) in Antalya , or in Sarıhan (1200–1250) in Avanos . In the latter, one long side of the courtyard is designed as an open arcade, the opposite side has closed rooms. A monumental main divan forms the entrance to the hall. In Tuzhisari Han in Kayseri (1202) there is a representative kiosk in the center of the inner courtyard, supported by four pillars on pointed arches. The passage under the pointed arch remains open in both main axes. The design of this kiosk with a prayer or lounge on the upper floor can also be found in the tombs. Steep stairs to the right and left of the arch in the main axis lead to a small mescite on the upper floor. These rooms were mostly domed. The domes are mostly no longer there today, and trumpets richly decorated with muqarnas ("stalactite vaults") can still be found frequently. The outer facade of the entrance portal is accentuated by a monumental iwan with a muqarnas niche and two massive bundled columns at the side.

The Agzikarahan (1231), approximately 15 km east of Aksaray also has a kiosk in the courtyard on. The courtyard does not have an ivan, instead the entrance portals are richly decorated and highlighted with ornaments and calligraphy. Here, too, there are closed rooms on one long side of the courtyard, while the other two sides have arcades open to the courtyard. Similar to the Tuzhisari Han in Kayseri, steep stairs to the right and left of the pointed arch lead up to the mescite on the upper floor. The undersides of the stairs are ornamented with muqarnas in the Ağzıkarahan. One of the largest Seljuk caravanserais is the Sultanhanı (1229) near Aksaray.

Tombs

The oldest known Seljuk tombs in Anatolia are the Halifet-Ghazi-Kumbet (1145–46), part of the Külliye of the Danish-Menden emir Halifet Alp ibn-Tuli in Amasya . The archaic-looking building once had a pyramid-shaped roof. The niche above the entrance is the oldest known stone muqarnas half-vault in the architecture of Asia Minor. The Sitte-Melik-Kumbet in Divriği , Sivas province, probably built in 1196 for the Mengücekid Emir Suleyman ibn Said al-Din Şahinschah (1162–1198), has a similar prismatic floor plan, but the ornaments of this building are much more elegant and designed more uniformly than that of the Halifet-Ghazi-Kumbed.

The mausoleum of Kılıç Arslan I (before 1192) in the courtyard of the Alâeddin Mosque in Konya has a twelve-sided floor plan . The tomb of İzzedin Kai Kaus in the darüşşifa of Sivas is decagonal. This monument was built by the architect Ahmad von Marand, whose name can be found in the monumental Kufic inscription made of turquoise, purple and white glazed mosaic on a red brick background above the main portal of the hospital. The octagonal doorway of the wife of Sultan Kai Kobad I , Hunat Hatun, in Kayseri has blind arches with richly decorated spandrels on each wall. The corners are adorned with small columns that rest on a muqarnas cornice and end in another cornice, which marks the transition to the pyramidal roof. Also in Kayseri is the doner kumbet, probably built around 1275 for the princess Shah Jihan Hatun. Its twelve sides are provided with blind pointed arches, over which a muqarnas ledge leads to the tent-like roof. Although made of stone, the roof panels are hewn in such a way that they look like sheets of lead. The construction of this kumbet is so similar to the architecture of the dome lanterns of Armenian churches of the 10th and 11th centuries that Hoag (2004) considers an Armenian influence to be likely.

See also

Web links

literature

- Oktay Aslanapa : Turkish art and architecture . Faber & Faber, London 1971, ISBN 978-0-571-08781-5 .

- Kurt Erdmann : The Anatolian Karavansaray of the 13th Century. Part 1 and 2: Berlin 1961; Parts 3 and 4 edited by Hanna Erdmann, Berlin 1976

- John D. Hoag: History of World Architecture: Islamic Architecture. Cape. 13: The classic Islamic architecture of Anatolia . Electa Architecture, 2004, ISBN 1-904313-29-9 , pp. 109-125 .

- Ayṣil Tükel Yavuz: The concepts that shape Anatolian Seljuq Caravansarais. Muqarnas Vol. 14 (1997), pp. 80-95 Online at Google Buch, accessed October 20, 2016

Individual evidence

- ^ Edmund Bosworth: The steppe peoples in the Islamic world. In: David O. Morgan, Arthur Reid (Eds.): New Cambridge History of Islam Vol. 2: The Eastern Islamic world - Eleventh to Eighteenth Centuries . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 2000, ISBN 978-0-521-83957-0 , pp. 37-53 .

- ↑ Peter Malcolm Holt, Ann Katharine Swynford Lambton, Bernard Lewis: The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol 1A . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 1977, ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4 , pp. 231 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ John D. Hoag: History of World Architecture: Islamic Architecture . Electa Architecture, 2004, ISBN 1-904313-29-9 , pp. 110 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Oktay Aslanapa : Turkish art and architecture . Faber & Faber, London 1971, ISBN 978-0-571-08781-5 , pp. 65-80 .

- ↑ Oktay Aslanapa: Turkish art and architecture . Faber & Faber, London 1971, ISBN 978-0-571-08781-5 , pp. 46-47 .

- ^ Daniel Schlumberger: Le palais ghaznévide de Lashkari Bazar. Syria 29 (3), 1952, pp. 251-270. Online at persee.fr , accessed October 25, 2016.

- ↑ Floor plan of the South Palace of Leşker-i Bāzār , accessed on October 23, 2016.

- ↑ Oktay Aslanapa: Turkish art and architecture . Faber & Faber, London 1971, ISBN 978-0-571-08781-5 , pp. 56-62 .

- ↑ Klaus Schippmann : The Iranian fire sanctuaries . W. de Gruyter, Berlin 1971, ISBN 3-11-001879-9 ( limited preview in the Google book search). (accessed on October 22, 2016)

- ↑ a b Stefano Bianca: courtyard house and paradise garden. Architecture and ways of life in the Islamic world . 2nd Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-48262-7 , p. 62-106 .

- ^ Francine Giese-Vögeli: The Islamic rib vault: origin - form - distribution . Gebr. Mann, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-7861-2550-1 , p. 66-88 .

- ↑ Fatema AlSulaiti: The style and regional differences of Seljuk minarets in Persia. In: Ancient History Encyclopedia. January 30, 2013, accessed October 23, 2013 .

- ↑ Oleg Grabar : Ivan. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam, p. 288

- ^ A b John D. Hoag: History of World Architecture: Islamic Architecture . Electa Architecture, 2004, ISBN 1-904313-29-9 , pp. 98 .

- ↑ Katharina Otto-Dorn: The Art of Islam . Holle Verlag, Baden-Baden 1982, ISBN 978-3-87355-128-2 , pp. 127 .

- ↑ André Godard : Gunbad-i-Qabus. In: Arthur Upham Pope, Phyllis Ackerman (Eds.): A Survey of Persian Art from Prehistoric Times to the Present . Oxford University Press, London / New York 1939–1958.

- ^ Sheila Blair, Jonathan Bloom: West Asia: 1000-1500. In: John Onians (ed.): Atlas of World Art . Laurence King Publishing, 2004, ISBN 978-1-85669-377-6 , pp. 130 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand: Islamic Art and Architecture . Thames & Hudson, 1999, ISBN 978-0-500-20305-7 , pp. 146 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Oktay Aslanapa: Turkish art and architecture . Faber & Faber, London Faber & Faber 1971, ISBN 978-0-571-08781-5 , pp. 93 .

- ↑ a b Oktay Aslanapa: Turkish art and architecture . Faber & Faber, London Faber & Faber 1971, ISBN 978-0-571-08781-5 , pp. 107-109 .

- ^ A b John D. Hoag: History of World Architecture: Islamic Architecture . Electa Architecture, 2004, ISBN 1-904313-29-9 , pp. 110-112 .

- ↑ Online, with illus. ( Memento of the original from June 17, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed October 25, 2016

- ^ A b c John D. Hoag: History of World Architecture: Islamic Architecture . Electa Architecture, 2004, ISBN 1-904313-29-9 , pp. 115-117 .

- ↑ Scott Redford: The Alaeddin Mosque in Konya reconsidered . Artibus Asiae Vol. 51, No. 1/2 (1991), pp. 54-74. JSTOR 3249676 , accessed October 30, 2016

- ↑ Oktay Aslanapa: Turkish art and architecture . Faber & Faber, London Faber & Faber 1971, ISBN 978-0-571-08781-5 , pp. 121-122 .

- ↑ UNESCO tentative list online , accessed October 24, 2016

- ↑ Ernst Kühnel : The Art of Islam . Kröner, Stuttgart 1962, p. 72 f .

- ↑ Ethel Sara Wolper: The Politics of Patronage: Political Change and the Construction of Dervish Lodges in Sivas. In: Muqarnas Volume XII: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture . EJ Brill, Leiden 1995, p. 39-47 . Online (PDF) , accessed on October 23, 2016.

- ^ John D. Hoag: History of World Architecture: Islamic Architecture . Electa Architecture, 2004, ISBN 1-904313-29-9 , pp. 117-119 .

- ↑ a b Ayṣil Tükel Yavuz: The concepts that shape Anatolian Seljuq Caravansarais. Muqarnas Vol. 14 (1997), pp. 80-95 Online at Google Buch, accessed October 20, 2016

- ↑ Kurt Erdmann : The Anatolian Karavansaray of the 13th Century Berlin 1961 and 1976

- ^ A b John D. Hoag: History of World Architecture: Islamic Architecture . Electa Architecture, 2004, ISBN 1-904313-29-9 , pp. 124 .