Ghazan Ilkhan

Inscription on the front: Arabic لا إله إلا الله محمد رسول الله صلى الله عليه وسلم ضرب تبريز في سنة ..., DMG lā ilāh illā 'llāh Muḥammad rasūl Allāh ṣallā' llāh ʿalaihi

wa-sallam ḍuriba Tabrīz fī sana…

“There is no god but God and Mohammed is his prophet; struck in Tabriz in the year… ”

Inscription on the reverse in Uighur and Arabic: Tengri-yin Küchündür. Ghazan Maḥmūd. Ghasanu Deledkegülügsen “By the power of Tengri . Ghazan Mahmud. This coin was minted for Ghazan. "

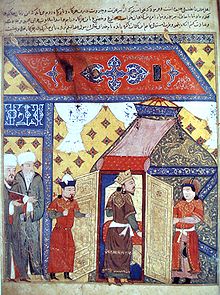

Mahmud Ghazan I. ( Mongolian ᠭᠠᠽᠠᠨ ᠬᠠᠭᠠᠨ Gasan Chaan , Persian محمود غازان, DMG Maḥmūd Ghazan ; * November 5, 1271 ; † 11. May 1304 ), in Western Europe as Casanus known was a Mongolian Ilkhan . He converted to Islam in 1292 , came to power in an overturn in 1295 and ruled Persia until his death . He raised the also converted Jew Raschid ad-Din to the position of vizier.

Life

Ghazan was the son of the Ilkhan Arghun and the Buluqhan-Chatun. He was the nephew of the former Ilkhan ruler Gaichatu and a cousin of his predecessor Baidu , whom he overthrew from the throne.

Ghazan was baptized as a child and raised a Christian . During his youth, he also studied Buddhism. Ghazan's wife was called Kökechin and came from China. Kublai Khan , the then ruler of China and also a descendant of Genghis Khan , commissioned (allegedly) Marco Polo to lead Kökechin.

Ghazan was an educated person who could speak several languages such as Chinese, Arabic and Franconian, which probably means Latin. Numerous Europeans were in the service of Ghazan and that also in high positions, for example the Italians Isol le Pisan or Buscarello de Ghizolfi .

Ghazan was the reformer among the Ilkhan people. He fought corruption (numerous executions of dignitaries), protected the farmers from attacks by the nomads and reduced their tax burden. He let the farmer z. B. allocate tax-free undeveloped land and cut taxes in stone or wooden steles to protect against arbitrary increases.

Behind his despotic reform frenzy, however, were tangible political problems. The Ilkhan commanded the army and paid for it with the income of the ingü , the great state domain, in money or in kind . The Ilkhan's problem here was the diminishing income from agriculture, so with the unsuccessful introduction of paper money (1293) he began to pay his troops by assigning state domains. This and the financial weakness resulting from the immense corruption of the time made reforms inevitable - if the state were not to dissolve prematurely.

Ghazan's conversion to Islam was essential for the dynasty's retention of power. In 1297 Ghazan put down an outbreak of Islamic fanaticism, which had been fueled by his brother-in-law, the Oiraten prince Nauruz (Nawrūz) and had him executed. Under Ghazan's brother and successor Öldscheitü (reigned 1304-1316) the time of religious tolerance that shaped Mongol rule ended. And Ghazan's reforms were sustained only to a limited extent.

Military campaigns

Although Ghazan later converted to Islam, he tried several times to conquer Muslim Syria . He also entered into alliances with Christian states, for example with Henry II of Cyprus , the titular king of Jerusalem . The Christian kingdom of Lesser Armenia and Georgians also fought with Ghazan. After Ghazan defeated the Muslims in Syria, he would hand over Jerusalem to the Christians.

After Ghazan, reacting to the rebellion of a vassal, put an end to the rule of the last atabeg of Yazd in 1297 and thus brought the central Iranian city under his direct control, he undertook several campaigns against Syria and the Mamluks in the winters of 1299 to 1303 :

Campaign of winter 1299/1300

In the summer of 1299, King Hathoum II of Lesser Armenia sent Ghazan a letter to get his support. Ghazan marched against Syria and wrote letters asking for the support of the Christians of Cyprus. The first letter was sent on October 21st and the second in November. There is no record of any response to Ghazan's letters.

Ghazan could take the city of Aleppo . King Hathoum II joined him there. The Mamluks were defeated in the battle of Wadi al-Khazandar on December 23 or 24. Part of the Mongolian army then chased the Mamluks all the way down to Gaza . The majority of the army marched against Damascus and was able to force the city to surrender between December 30, 1299 and January 6, 1300, although the city's citadel held. In February Ghazan withdrew most of his army to Persia but promised to return the next winter to attack Egypt.

In the meantime 10,000 Mongolian horsemen under General Mulay held the position in Syria. They went on forays to Jerusalem and Gaza. But the Mameluks were able to drive the Mongols out of Syria in May 1300.

Campaign of winter 1300/01

In February 1301 Ghazan invaded Syria again with about 60,000 men. But he couldn't do more than a few forays. This time Kutluschah (Cotelesse in Frankish sources) was supposed to protect Damascus with 20,000 riders. But again the Mongols had to withdraw.

Sources and literature

- Ghazan Ilkhan . In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica (English, including references)

- Adh-Dhababi: Record of the destruction of Damascus by the Mongols in 1299–1301 , translated by Joseph Somogyi. From: Ignace Goldziher Memorial Volume, Part 1, Online (English translation).

- Jean de Joinville : The Memories of the Lord of Joinville , translated by Ethel Wedgwood. Online (English translation).

- Le Templier de Tyr (circa 1300). Chronicles of the Templier de Tyr , online (French).

- Hetoum of Korykos (1307). Flowers of the History of the East , Online (English translation).

- William of Tire (circa 1300): History of the Crusader States , online (French).

- Kirakos (circa 1300): History of the Armenians , Online , (English translation).

- The story and life of Rabban Bar Sauma , ( online )

- Alain Demurger: Jacques de Molay (French). Editions Payot & Rivages, 2007, ISBN 2-228-90235-7

- Sylvia Schein: Gesta Dei per Mongolos 1300. The Genesis of a Non-Event Published in The English Historical Review . 94 (373), pp. 805-819, October 1979

- Sylvia Schein: Fideles Crucis: The Papacy, the West, and the Recovery of the Holy Land. Clarendon Verlag 1991, ISBN 0-19-822165-7

- Sylvia Schein: Gateway to the Heavenly City: crusader Jerusalem and the Catholic West . Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005, ISBN 0-7546-0649-X .

Individual evidence

- ↑ For more numismatic information: Coins of Ghazan ( Memento of the original from February 1, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Ilkhanid coin reading ( Memento of the original from February 1, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ "Ghazan had been baptized and raised a Christian," Richard Foltz , Religion of the Silk Road S. 128

- ↑ Ghazan was a man of high culture. Besides his mother tongue, he more or less spoke Arabic, Persian, 'Indian', Tibetan, Chinese, and 'Frank', probably Latin. In: Jean-Paul Roux: Histoire de l'Empire Mongol. P. 432.

- ↑ Roux, p. 410.

- ↑ Malcolm Barber: The Trial of the Templars. 2nd edition, p. 22: “The aim was to ally with Ghazan, the Mongolian Ilkhan of Persia, who had invited the Cypriots to participate in an enterprise against the Mamluks.” (“The aim was to link up with Ghazan, the Mongol Il-Khan of Persia, who had invited the Cypriots to participate in joint operations against the Mamluks. ")

- ↑ Demurger, p. 143

- ↑ Demurger, p. 142 (French) “He was soon joined by King Hethum, whose forces seem to have included Hospitallers and Templars from the kingdom of Armenia, who participated to the rest of the campaign.”

- ↑ Demurger, p. 142 “The Mongols pursued the retreating troops towards the south, but stopped at the level of Gaza”

- ↑ Demurger, p. 142

- ^ Runciman, p. 439

- ↑ Demurger, p. 146

- ^ Demurger (p. 146, French edition): "After the Mamluk forces retreated south to Egypt, the main Mongol forces retreated north in February, Ghazan leaving his general Mulay to rule in Syria".

- ^ "Meanwhile the Mongol and Armenian troops raided the country as far south as Gaza." Schein, 1979, p. 810.

- ↑ “He pursued the Saracens as far as Gaza and then returned to Damascus, conquering and destroying the Saracens. Original "Il chevaucha apres les Sarazins jusques a Guadres et puis se mist vers Domas concuillant et destruyant les Sarazins." Le Templier de Tyr, # 609

- ^ Jean Richard, p. 481

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Baidu |

Ilkhan of Persia 1295-1304 |

Öldscheitü |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ghazan Ilkhan |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Ghazan, Mahmud; Mahmud Ghazan I. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Mongolian Ilkhan of Persia |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 5, 1271 |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 11, 1304 |