Turkic peoples

Turkic peoples denotes a group of around 40 ethnic groups in Central and West Asia as well as in Siberia and Eastern Europe , whose languages belong to the Turkic language family . This includes the Turkish language and around 40 relatively closely related languages with a total of around 180 to 200 million speakers.

The science of the languages, history and cultures of the Turkic peoples is Turkology . Pan-Turkism describes the political and cultural movement that emerged in the 19th century, which aims at the community of the Turkic peoples. The cultures, traditional economic forms and ways of life of the individual Turkic peoples are diverse, their history is complex (see also the list of Turkic peoples ).

Other names

The Turkic peoples are sometimes incorrectly referred to as “Turkic peoples”, “Turkish peoples” or “Turks”. In order to avoid confusion with the living in Turkey today ethnic groups, which are referred there by law officially called "Turks" with the rest of a Turkic-speaking nations, it is in Europe become common, this generally as "Turkic" ( English Turkic people ). “Turk” is used there without exception to the citizen of the Republic of Turkey or, in the narrower sense, to the speaker of Turkey-Turkish . The practice of distinguishing between the actual Turks and other Turkic-speaking ethnic groups had its origins in 19th century Russia .

In contrast, in Turkic Turkology, it is common practice to speak of the “Turkish peoples” ( Turkish: Türk halkları ) or simply generally of “Turks” ( Turkic ).

Some researchers have disregarded a previously suspected Ural-Altaic language family or a linguistic union with the Altaic languages , which also includes the Mongolian language and the Tungusian language, and therefore the direct connection between the Turkic and the Tungus is valid among these researchers Altaic languages as controversial.

Origin of name

The name "Turk" is derived from the name of a nomadic tribal federation of the 6th century who called themselves Turk or Türük and were led by the Ashina clans . The exact origin of the word is unknown or its origin is disputed.

The term “Turk” first appeared in AD 552, when the “Türük” tribe founded their tribal federation, which is known today as the “Empire of the Gök Turks” (sometimes also spelled “Empire of the Kök Turks”). Gök Türük or kök Türük means celestial or blue turks. This martial tribal federation was referred to by the Han Chinese as 突厥 Tūjué, older transcriptions are T'u-chüeh, Tu-küe or Tür-küt . This designation is obviously derived from the name Türk .

The etymology of the words gök / kök (meaning: blue or sky) and turük is unclear and controversial. Influence from the various Iranian- speaking peoples of Central Asia ( Scythians ) is often suspected, however, since almost all titles can apparently be derived from Iranian languages. The name of the leading clan ( Aschina ) was probably borrowed from Saki and meant blue (cf. Old Turkish gök = "blue"). The names of the founders of the empire, Bumın Kagan and Iştemi, are also of non-Turkish origin. But it also seems that other concepts of rule such as Kaġan , Şad, Tegin or Yabgu can be derived from other languages.

Some suspect that the word Türk or Türük has a Tibeto-Burmese origin . Türk or Türük probably meant “origin” or “born” in Old Turkish. In Tibetan there is the word duruk or dürgü which also means “origin” or “we”. Even today, the self-designation of some Tibetan Burman peoples is Druk .

According to Josef Matuz , the original home of the Turkic peoples reached in the north beyond Lake Baikal into today's Siberia, in the west it was bordered by the Altai and Sajan Mountains , in the east by the Tian Shan mountains and in the south by the Altunebirge in today's Xinjiang . Michael Weiers assumes that at the end of the 3rd century various tribes appeared in what is now northern China, which he referred to as "ancient Turks". Several other tribes clustered around this core. According to Greek, Persian and Chinese sources, the following important tribal associations were staying there: Xiongnu-Hu (so-called Eastern "Huns"), the Tab'a , the Hunnic Xia and the Turkish and proto-Mongolian Rouran .

Origin and Organization of the Early Turkic Peoples

The origin of today's Turkic peoples is disputed. It is believed to be a region between Central Asia and Manchuria in northeastern China . The early Turks were genetically and culturally closely related to Mongols and Han Chinese . Some researchers see the Xinglongwa culture along the Liao He as the origin of the early Turks.

They became historically tangible from the 6th century BC. Thus, among others, the Turk are associated with the Xiongnu , whose vassals and armourers they were. In 177 BC The Chanyu of the Xiongnu Mao-tun drove out the competing Yuezhi and established its tribal federation as the most important power in what is now Mongolia and East Turkestan . The Xiongnu are often considered to be the ancestors of today's Turkic peoples and the Mongols . But this thesis is considered controversial and could not be clearly proven. However, it is undisputed that the Xiongnu partly used the forerunners of today's Turkic languages or that at least the ruling class in this federation was Turkic and another part used Old Mongolian and Tungusic languages. So they are mainly described and referred to as "Turkic-Mongolian".

Not much is known about the Xiongnu language. There are only a few personal names and words from warfare and everyday life. Although the few known words indicate a close connection to the Turkic languages, they do not prove that the Xiongnu were exclusively Turkic-speaking. Josef Matuz expressly points out the difficulty in assigning the Huns (whereby the Huns in the west are to be separated from the Xiongnu and the Iranian Huns ) to the Turkic peoples:

“Hypotheses according to which the European or Asian Huns, the latter mentioned in the Chinese annals under the name Hiung-nu , were Turks cannot be proven due to a lack of tradition. The same applies to the Juan-Juan [Rouran], the Asian and also to the European Avars . "

This problem is generally recognized.

After the collapse of the Xiongnu Empire, the Turk belonged to the Rouran Empire , which was also organized nomadically. Here, too, the Turk were initially only vassals and arms manufacturers of the new ruling class.

The tribal federation of the Turk was divided into individual sub-tribes ( old Turkish bodun ). The Turk ruled a territory ( El ) and had facilities ( törö ). The sub-tribes often named themselves after one of their founders.

history

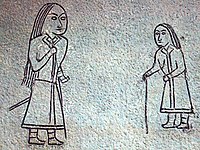

prehistory

The tribal federation of the Turk were at first just an amalgamation of different nomadic tribes, basically just a community of interests that advocated the expansion of their pastures and the control of the few oasis towns . But before this tribal federation itself became a Central Asian power factor, it performed vassal services for other nomadically organized tribal associations, such as the Xiongnu and the Rouran.

The kingdoms of the Gök Turks

Due to the refusal of the last Rouran -Fürsten, the Khan of the door, Bumin give a princess for a wife, this assumed the supremacy of the former Chinese empire and smashed in the year 552, the steppe kingdom of Rouran. The first Türk Kaganat comprised the area between the Chinese border, today's Mongolia , the Xinjiang and the Caspian Sea . His sphere of influence extended from Lake Baikal in the north over today's Kazak steppes to the Black Sea .

Initially, the name Türk was reserved for the nobility only and over time it became a purely tribal name. The founder of the empire Bumın (552) died early and the empire was divided: The western empire was ruled by Iştemi (Bumın's brother), the more important eastern empire with Ötükän (today's Changai Mountains ) , which is sacred to all steppe nomads, by Bumın’s son Muhan. The history of the empire was recorded for posterity under a later ruler in stone stelae inscribed with Orkhon runes . The Turks were first mentioned in western sources by the late antique historian Theophanes of Byzantium (late 6th century).

The Eastern Empire sank into a Chinese province from 580, since from that point on it was without exception under the suzerainty of the Chinese emperor. The western empire was able to hold out longer: it concluded an alliance against the Hephthalites with the Iranian Sassanids around 560 . After their joint victory, however, they fell out, partly due to trade interests. The Turks then turned on the advice of the influential Sogdier Maniakh (the Sogdians played a leading economic role in late ancient Central Asia and also served in the administration) to the Byzantine Empire .

Under their ruler Tardu (ruled from 575/76 to 603), the successor of Iştemis (see Sizabulos ) and possibly a brother of Turxanthos , the western empire broke away from the eastern empire in 584 and began its own with the consent of the Sui dynasty then ruling in China Expand sphere of influence. Here appeared Tardu officially an ally of the Chinese emperor. In this way, the western empire managed to expand its territory and Tardu also entered into diplomatic relations with Byzantium in his war against the rival Avars. However, when the Byzantines allied themselves with them, there were armed conflicts between the Turkish Western Empire and the Byzantine Empire.

In the years 588 and 589, the Turks of the Western Empire, who now called themselves On-Ok (People of the Ten Tribes), went to war several times against the Sassanids and reached Herat .

After Tardu's death, a few insignificant khagans followed, of which only the Chinese names are known. Under Khagan Tong Yehu, the western empire was able to conquer some parts of the eastern empire, so that it reached from the Altai to the Caspian Sea. After Tong's death, the Turkish western empire was gradually converted into Chinese protectorates from 657 onwards and finally incorporated into the entire Chinese state in 659.

After the incorporation of the Western Empire, the first uprisings of the early Turkic peoples against the Chinese began in 679. So who made his 683 ashina - Prince Kutlug on to unite the various Turkish tribes under his leadership. As Elteriş ( imperial collector ) he became the new ruler of the Turks, founded the Second Turk Kaganat and began targeted raids into Chinese territory. This time is in the resulting stone pillars 727 on Orchon described whose construction the former Minister Tonyukuk is attributed.

The heirs of the Gökturk empires

With the end of the Second Turk Kaganat , further Turkic nomadic states emerged. These were once vassals of the western Turkish empire and were able to go their own way after its fall. Between the 6th and 11th centuries , the Khazars established another Turkish empire in what is now southern Russia , the upper class of which was derived from the Turk and their tribes from an Ogur people. In contrast to most of the other Turkic peoples, the Khazars adopted Judaism as the state religion.

Around 744 or 745 the Uighurs rose against the rule of the Turk . They killed the last reigning khagan of the Turk, Ozmış, smashed their nomadic state and established the Uyghur Kaganat , a separate rule in the area inhabited by Turkic peoples. The Uighurs knew how to break away from the nomadic traditions of their predecessors and to build very good relationships with their Chinese neighbors. The Iranian- speaking Sogdians held an important position in the Uighur empire , because their ruler Bögü made contact with the Sogdian Manicheans as early as the late 750s. In the course of these relationships, the Uyghurs converted to Manichaeism in 762 , which replaced the old religion of Tengrism . As a result, the Uighurs were also the first Turkic people to adopt a recognized high religion.

Around 840 the Kyrgyz who settled on the Yenisei rose against the Uyghur supremacy and in a short war they smashed the Uyghur empire. The Kyrgyz took the place of a new ruling class and established the Kyrgyz Empire , but this new Turkish Empire was already characterized by nomads again. The Yenisei-Kyrgyz of that time are described by Chinese historians predominantly as blond to red-haired and with blue and green eyes and are considered the descendants of the Dingling and K'ien-K'un. Undoubtedly, the Kyrgyz have borrowed from them the myths in which the mythical wolf is replaced as the husband of young girls by a red dog. Many Turkic peoples believed that they descended from or were closely related to wolves.

The surviving Uyghurs eventually migrated to the south and southwest, where they founded two new Uyghur empires. Of these, the West Uyghur Empire of Qoço existed the longest, as it voluntarily submitted to the Mongol rule of Genghis Khan in 1209 and remained under Chinese rule until the end of the Yuan dynasty . The Uyghur empire in the Tarim Basin was already wiped out in 1028 by a people of Tibetan origin , the Tanguts .

In 1090 and 1091 the Turkic Pechenegs reached the walls of Constantinople , where Emperor Alexios I, with the help of the Kipchaks, destroyed their army. From the 9th century, the Pechenegs began a difficult relationship with the Kievan Rus . In 914 Igor of Kiev succeeded in subjugating the Pechenegs and making them subject to tribute. In 920 the climax of the fighting took place. In 943 there were also temporary military alliances between Pechenegs and Byzantines . In 968 the Pechenegs besieged the city of Kiev . In the following years, part of the Pechenegs made an alliance with Igor's son Svyatoslav I , the new prince of Kiev. In the years 970–971 they started campaigns against the Byzantines together. In 972 Svyatoslav I died in an ambush by the Pechenegs. The Pechenegs were eventually ousted by the Kipchaks. In what is now Tatarstan , an ethnic synthesis between the Kipchak and the Oghur branches of the Turkic peoples developed. This ethnic synthesis formed the core population of the khanates of Kazan , Astrakhan , Kasimov and Sibir (see Golden Horde ).

Introduction of Islam and the rise of Turkish military slaves

When the Arabs invaded Central Asia in the 8th century, this had two effects on the Turkic tribes: On the one hand, many Turkic peoples were converted to Islam . The Turkic dynasty of Qarakhanid was 999 the first converted. Islam was established as the only religion in their area; the Qarakhanids conquered Bukhara and overthrew the Persian Samanids . The jihad of the Samanids against the Central Asian nomads played a central role in the conflict between the two dynasties , but it was essentially politically motivated and only served to expand their own army. In the 12th century the Karakhanid Empire was subjugated by the Mongolian Kara Kitai .

Above all, however, the Turks served as military slaves ( Mamluks ) since the Abbasid rule, as they soon became a central power factor, de facto ruling large parts of the Islamic world and establishing their own dynasties and empires. The first great empire founded by a Muslim Turk was that of the Sultans of Ghazna . In 961 Alp-Tigin , a former Mamluk in the service of the Samanids, came to power and replaced the late ruler Abd al-Malik in Balch in the Persian Khorasan as regional prince. In Zabul he established a small principality which later expanded under his successor. However, his son Mahmud (989-1030) is considered to be the actual founder of the dynasty. Although the Ghaznavids were ethnic Turks, historical documents and biographies cast strong doubt that they saw themselves as such. As a Persian-speaking family that had also been culturally assimilated by the native population of Khorasan, the Ghaznavids were the beginning of a cultural phenomenon within Muslim society that only ended with the triumph of the later Ottomans (see below): descendants of nomadic Turkic tribes became the Converted to Islam, adopted the Persian or Arabic language and spread this culture to other regions ( India , China , Anatolia ).

From the Seljuks to the Ottoman Empire

The greatest adversary of the Ghaznavids was again a Turkish dynasty, the Seljuks . This Oghuz clan first settled on the shores of the Aral Sea before they established a great empire in the 11th century and even brought the caliphate under their control. Pressing the Byzantine Empire, the Seljuks also advanced to Anatolia and founded several dynasties there. One of them was the Ottoman , founded in 1299 , which was derived from a Seljuk petty prince named Osman . The Ottomans were originally a small Turkmen tribe to whom the Sultan of the Rum Seljuks left a small principality ( Beylik ) on the border with the Byzantine Empire. Most of the Turks in Turkey see themselves as descendants of the Ottoman Turks. These, in turn, were members of the so-called "Western Ooghuz". The origin of these tribes, known as Oghusen , is in what is now Mongolia.

religion

Today most of the Turkic people are Muslims , the majority of them Sunnis , Shiites and Alevis . There are also members of other religions such as Tengrists , Buddhists , Jews (especially Karaites or Crimchaks ) and Christians .

The Urum , Gagauz or Tschuwaschen have professed Orthodox Christianity for centuries. In the Siberian Turkic peoples is partly shaman belief still practiced, especially by the Khakas or Altaians (see Altai shear shamanism ). Some Siberian Turkic peoples have adopted the Orthodox faith or practice it syncretically with shamanism. The Tuvins are predominantly Buddhist- Lamaist .

Writing and language

The Proto Turkish , so the language of origin of all living Turkic languages, has not yet reconstructed. However, attempts to do this have already been made.

In the early Middle Ages, the Turkic peoples used a rune-like writing system that science now calls Runic Turkish . This writing system was later replaced by a Semitic writing system called the Syro-Uighur alphabet, which is the basis of today's Mongolian alphabet . After the adoption of Islam, the Arabic alphabet prevailed among the Turkic peoples .

In the 1920s, the Arabic writing systems began to be replaced by Latin ones (see Turkish Latin alphabets ). But as early as the 1930s, most of them were converted to a Cyrillic alphabet . Today's Turkey alone has only used the Latin alphabet since 1928, while the Turkic-speaking minorities in the Arab states, Iran and Afghanistan continue to work with the Arabic writing systems.

With the collapse of the former Soviet Union (from 1989), most of the Turkic peoples decided to carry out a new Latinization in the area of the former USSR. With the exception of the states of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan , this has now been carried out there. In Kazakhstan, the conversion to the Latin alphabet should be completed by 2025. Kyrgyzstan justifies keeping the Cyrillic alphabet - like Kazakhstan before - with the Russian minority in the country.

The Turkic languages form one of the larger language families in the world. They are scattered from the Eastern European Balkans through Turkey and the Caucasus to the Central Asian and Siberian settlement areas. Nevertheless, they are still very closely related to one another, both in terms of their grammatical structure and basic vocabulary . Because of this close linguistic relationship, there is an oral intelligibility between them, but sometimes with difficulties. A suspected language family or a linguistic union with the Altaic languages , which also includes the Mongolian language and the Tungusian language , is disputed by some researchers today.

The Turkic languages are divided into four groups:

- Southwestern group (Oghusian group)

- Northwestern Group (Kyptchak Group)

- Southeastern group (Turkish or Uighur group)

- Northeast Group (Siberian Group)

The current classification of the Turkic languages is given in the article there.

Gallery: The current distribution of the Turkic peoples

See also

- List of Turkic peoples and tribes

- Turkic States ( Turkic Republics)

- Economic Cooperation Organization (regional economic alliance that includes the Turkic states)

- Turkestan (old Persian name)

- Old Turkish language (earliest written Turkic language)

- Tengrism (religion of the sky god Tengri)

literature

- K. Heinrich Menges: The Turkic Language and People. Wiesbaden 1968 (English).

- Colin Renfrew: Archeology and Language. The Puzzle of Indoeuropean Origins. Jonathan Cape, London 1987, pp. 131-133 (English).

- Wolfgang-Ekkehard Scharlipp : The early Turks in Central Asia. An introduction to their history and culture. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1992, ISBN 3-534-11689-5 .

- Peter Benjamin Golden : An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples. Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1992, ISBN 3-447-03274-X (English).

- Colin Renfrew : World Linguistic Diversity. In: Scientific American. Volume 270, No. 1, 1994, p. 118 (English).

- Jalal Mamadov, Vougar Aslanov: Turan. Mysterious empire of the Turkic peoples. In: Vostok . Information from the east for the west. Issue 2. Berlin 2003, ISSN 0942-1262 , pp. 75-77.

- Carter Vaughn Findley: The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press, New York 2005, ISBN 0-19-517726-6 (English).

- Bert G. Fragner, Andreas Kappeler (Ed.): Central Asia. 13th to 20th century. History and Society (= Edition Weltregionen. Volume 13). Promedia, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-85371-255-X .

- Ergun Çağatay, Doğan Kuban (Ed.): The Turkic Speaking Peoples. 2,000 Years of Art and Culture from Inner Asia to the Balkans. Prestel Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-7913-3515-4 .

- Udo Steinbach : History of Turkey. 4th edition, revised and updated. Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-44743-3 .

Multi-volume work:

- Jean Deny et al. a. (Ed.): Philologiae Turcicae Fundamenta. Volume 1: Languages of the Turkic Peoples. Wiesbaden 1959.

- Louis Bazin et al. a. (Ed.): Philologiae Turcicae Fundamenta. Volume 2: Literatures of the Turkic Peoples. Wiesbaden 1964.

- Hans Robert Roemer (Ed.): Philologiae Turcicae Fundamenta. Volume 3: History of the Turkic Peoples. Schwarz, Berlin 2000; English: Wolfgang-Ekkehard Scharlipp (Hrsg.): History of the Turkic Peoples in the Pre-Islamic Period. Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-87997-283-4 .

Web links

- Entry: Turks [X: 686b]. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition . Archived from the original on December 16, 2005 (English, possibly with display problems; extensive treatise on the history, languages, literature, music and folklore of the Turkic peoples).

Individual evidence

- ^ Peter Benjamin Golden : An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples. Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1992, ISBN 3-447-03274-X , p. 1.

- ↑ Carter Vaughn Findley: The Turks in World History. P. 6.

- ↑ Carter Vaughn Findley: The Turks in World History. P. 38.

- ↑ Golden, Peter B. "Some Thoughts on the Origins of the Turks and the Shaping of the Turkic Peoples". (2006) In: Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World. Ed. Victor H. Mair. University of Hawai'i Press. p. 143

- ↑ Wolfgang-Ekkehart Scharlipp: The early Turks. P. 14.

- ↑ Cf. M. Weiers: Kök-Türken. (PDF; 141 kB) 1998.

- ↑ Wolfgang-Ekkehard Scharlipp: “[…] Much has been puzzled over the ethnogenesis of this tribe. It is noticeable that many key terms are of Iranian origin. This affects almost all titles. Some scholars want to trace the self-term turk back to an Iranian origin and to associate it with the word Turan, the Persian name for the land beyond the Oxus. ”In: The early Turks in Central Asia. P. 18.

- ↑ Carter Vaughn Findley: “The linguistically non-Turkic name A-shih-na probably comes from of the Iranian languages of Central Asia and means blue […].” In: The Turks in World History. P. 39.

- ↑ Carter Vaughn Findley: “[…] The founders of the Turk Empire, Istemi and Bumin, both had non-Turkish names […]. Far from leading to a pure national essence, the search for Turkic origins leads to a multiethnic and multilingual steppe milieu. " In: The Turks in World History. P. 19.

- ↑ a b c d e Peter Zieme: The Old Turkish Empires in Mongolia. In: Genghis Khan and his heirs. The Mongol Empire. Special volume for the exhibition 2005/2006, p. 64.

- ↑ Hayrettin İhsan Erkoç: Elements of Turkic Mythology in the Tibetan Document PT 1283 . In: Central Asiatic Journal . tape 61 , no. 2 , 2018, ISSN 0008-9192 , p. 297-311 , doi : 10.13173 / centasiaj.61.2.0297 .

- ↑ Josef Matuz: The Ottoman Empire. Baseline of its history. 5th edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2008, pp. 9 and 323.

- ↑ Cf. M. Weiers: Turks, Proto-Mongols and Proto-Tibetans in the East. (PDF; 21 kB) 1998.

- ↑ Bayazit Yunusbayev, Mait Metspalu, Ene Metspalu, Albert Valeev, Sergei Litvinov: The genetic legacy of the expansion of Turkic-speaking nomads across Eurasia . In: PLoS genetics . tape 11 , no. 4 , April 2015, ISSN 1553-7404 , p. e1005068 , doi : 10.1371 / journal.pgen.1005068 , PMID 25898006 , PMC 4405460 (free full text): "The origin and early dispersal history of the Turkic peoples is disputed, with candidates for their ancient homeland ranging from the Transcaspian steppe to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. "

- ↑ (PDF) Transeurasian ancestry: A case of farming / language dispersal. Retrieved September 6, 2019 .

- ^ Wolfgang-Ekkard Scharlipp: The early Turks. P. 9.

- ↑ Klaus Kreiser: Brief history of Turkey. Stuttgart 2003, p. 20.

- ↑ Carter Vaughn Findley: The Turks in World History. P. 28.

- ^ Wolfgang-Ekkehard Scharlipp: The early Turks. P. 2.

- ↑ Josef Matuz: The Ottoman Empire. Baseline of its history. 6th edition. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-89678-703-3 , p. 9.

- ↑ Carter Vaughn Findley: “[…] The Xiongnu were a confederation of tribal peoples. As usual in tribal societies, their confederation and even the member tribes were probably polyethnic in origin. [...] It has been widely held that the Xiongnu, or at least their ruling clans, had or were acquiring a Turkic identity, or at least an Altaic one. [...]. " In: The Turks in World History. P. 28 f.

- ↑ a b c d e Peter Zieme: The Old Turkish Empires in Mongolia. In: Genghis Khan and his heirs. The Mongol Empire. Special volume for the exhibition 2005/2006, p. 65.

- ↑ a b c d e cf. Josef Matuz: Das Ottmanische Reich. Baseline of its history. 6th edition. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-89678-703-3 , p. 10 ff.

- ↑ Ulla Ehrensvärd, Gunnar Jarring (ed.): Turcica et orientalia (= Svenska Forskningsinstitutet [ed.]: Transactions. No. 1). Stockholm 1988, ISBN 91-86884-02-6 , p. 54.

- ^ Werner Leimbach: Geography of Tuwa. The area of the Yenisei upper reaches (= A. Petermann's communications from Justus Perthes' Geographischer Anstalt. Supplementary booklet No. 222). J. Perthes, Gotha 1936, p. 98 (Zugl .: Erw. Königsberg, Phil. Diss.).

- ^ Jean-Paul Roux: The old Turkish mythology. The wolf. In: Käthe Uray-Kőhalmi, Jean-Paul Roux, Pertev N. Boratav, Edith Vertes: Gods and Myths in Central Asia and Northern Eurasia (= Egidius Schmalzriedt , Hans Wilhelm Haussig [Ed.]: Dictionary of Mythology. Volume 7.1). Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-12-909870-4 , p. 204.

- ↑ Peter Zieme: The Old Turkic Empires in Mongolia. In: Genghis Khan and his heirs. The Mongol Empire. Special volume for the exhibition 2005/2006, p. 67.

- ↑ Steven Lowe, Dmitriy V. Ryaboy: The Pechenegs ( Memento of October 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive ). In: geocities.com .

- ↑ a b Compare the special exhibition Linden Museum Stuttgart : The Long Way of the Turks. ( Memento from December 11, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) September 13, 2003 to April 18, 2004.

- ↑ See Ghaznavids. In: Encyclopaedia Iranica ( iranica.com [online version]).

- ^ Compare Richard Hooker: The Ottomans: Origins. ( Memento of May 14, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) In: World Civilizations. 1996 (English).

- ^ Gerhard Doerfer Proto-Turkic: Reconstruction Problems. In: Belleten. 1975/1976.

- ^ Brigitte Moser, Michael Wilhelm Weithmann: Regional studies of Turkey: history, society and culture. Buske Verlag, 2008, p. 173.

- ↑ German Orient Institute: Orient. Volume 41. Alfred Röper, 2000, p. 611.

- ^ Heinz F. Wendt: Fischer Lexicon Languages. Chapter Turkic languages, p. 317.

- ↑ See Turkology ( Memento from June 15, 2006 in the Internet Archive ). In: orientalistik.uni-mainz.de. Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz , accessed on September 5, 2019.