Islamic ceramics

The term Islamic Ceramics is a collective term for from clay made use and ceremonial goods from areas with a predominantly Muslim population. While the processing and artistic design of ceramics was often seen as a minor trade in Europe, it is considered one of the most important handicrafts in Islamic art . It was strongly stylistically influenced by Chinese porcelain , which has been imported since the 8th century.

The history of the development of decorative processing of ceramics in Islamic culture often ran stylistically parallel to that of glass and metal goods . Ceramic art reached its first heyday under the rule of the Abbasids ; later the Seljuk kashan in Persia and, in the 15th century, the Ottoman İznik in western Anatolia became the most important center for the production of glazed Islamic ceramics.

Research on ceramics in the Islamic world

Despite the complexity of the subject, Islamic ceramics have been relatively well researched, which is made possible primarily by the scientific investigation of the materials used and laboratory analyzes for the reconstruction of the objects. In addition, the production process was rarely described in medieval Arabic and Persian scripts, often in the form of scattered anecdotes apart from the actual subject matter of the texts. In some cases, however, the topic is dealt with in more detail: Above all, the Kitab al-Jamahir fi ma'rifat al-Jawahir , a book on mineralogy by the Khorezmian universal scholar al-Biruni from the year 1035, which contains some recipes for enamels are listed, as well as the treatise of a Persian potter named Abū'l-Qāsim from the year 1301 with detailed information on the manufacturing process and the materials to be used.

Since ceramics is a collective handicraft and the objects are usually not signed, the names of the potters and decorators are only known in rare cases. Some workshops, which gained a particularly high reputation due to the first-class quality of their work, have been handed down by name. Due to the supra-regional trade in ceramic works of art, the production sites are also often unknown. Archaeological excavations , in which ovens, tools and ceramics that were discarded due to defects and disposed of on site, can often provide information here.

Forms of Islamic Pottery

The collective term for Islamic ceramics includes objects of daily use and art from very different epochs and areas, which are sometimes only comparable to a limited extent, including earthenware from the early Abbasid period , lusterware from Andalusian Spain and chips from Iran of the Great Seljuks . A more detailed description of manufacturing and design techniques is therefore only possible for a limited time and region.

Islamic ceramics can also be roughly divided into two main forms: tiles, which were mainly used as wall coverings, and vessels and figurative artefacts, which were used as household goods or for decoration. However, both branches of the craft are closely linked due to similar production techniques, the motifs and the performing artist. The very variable quality of the vessels suggests that ceramics were not only valued at court, but were also accessible to lower-ranking groups of people as consumer goods. However, finer and high-quality handicrafts were without a doubt valued luxury goods and as such were reserved exclusively for the social elite.

historical development

Umayyad period (8th century)

From the Umayyad period, only simple pottery has survived, which in terms of technology, decoration and shape still fully corresponds to the legacy of previous cultures, in particular that of the Parthians , Sassanids and Byzantines . This poses some problems for dating, for example in the case of the ceramic finds from the ancient Persian city of Susa . The unglazed finds of different quality and uses often cannot be clearly assigned to a specific time due to the cultural continuity. Some Umayyad objects such as a green and yellow colored clay jar from Basra have already been glazed . However, it was only from the beginning of the 9th century that it was possible to speak of a distinctly Islamic ceramic with its own technique and original style.

Abbasid period (9th and 10th centuries)

Even though unglazed ceramics were still in use and made up the largest proportion of pottery in terms of quantity, the most significant developments in ceramic art since the Abbasid period in the field of glaze took place. The addition of quartz to the clay resulted in chips that could be fired at significantly higher temperatures and thus into finer, semi-transparent shards. The earliest Islamic alkali glazes were based predominantly on lead oxide , which was mainly used in the manufacture of open tableware.

The 9th century saw two major and enduring innovations: faience and luster . The increasing import of Chinese ceramics, especially porcelain, which served as a model for the potters, is often considered to be the decisive factor for these developments; however, some of the Islamic achievements precede the influence from China or are to be regarded as independent of it. However, the lack of suitable clay and the technical possibility of reaching correspondingly high temperatures during the firing process meant that the potters were denied the technical ability to produce real porcelain based on the Chinese model.

According to al-Ya Keramikqūbī , the centers of Abbasid ceramic production were in Kufa , Basra and Samarra . Even Baghdad and Susa are likely many famous potters hosts.

The first faiences

Faience was mainly used for the production of blue and white colored decorations, as they were popular and widespread in China and, much later, also in Europe; Examples of turquoise, green, brown or aubergine-colored faiences, on the other hand, are much rarer. Instead of lead oxide, tin frits were used, which made the glaze shimmer white and semi-transparent and colored more easily. The white engobe was then applied to the porous, reddish shards of the earthenware. The oldest products of this technique, which date from the 9th century, were found in the palace ruins of Samarra; probably they originally came from the Basra pottery.

Faience was mainly used for open tableware and for vegetable, geometric and calligraphic motifs. The blue coloration typical of many ceramics was achieved through the use of cobalt pigments , a technique that was originally developed in Basra and which quickly spread to Syria and Egypt. The faiences from the Abbasid heartland were also copied in Persia and the Maghreb, but greenish colors were preferred here. It is not uncommon for ceramic works of art from the provinces to surpass their models from Mesopotamia: The decorations made under Samanid and Tahirid rule in Afrasiab and Nischapur , for example, were created on the basis of careful planning with the help of paper drafts, which makes the calligraphic inscriptions on the pottery much more elegant and stylish could be executed.

Luster

While faience initially only appeared in the form of vessels, lustered ceramics is documented in the form of wall tiles as early as the ninth century through the decor of the mihrāb of the great mosque of Kairouan , which consists of 139 chandelier tiles. According to written evidence, the tiles were originally supplied by a master from Basra around 862, but the design of the motif also shows clear East Islamic influences. Other early examples of luster ceramics were found in Samarra . The technology was probably originally developed by the glass manufacturers - the oldest object is probably a lustful glass beaker, which can very probably be dated to the year 773. The production of luster ceramics was extremely complex and expensive: the already glazed and fired pottery was coated with a layer of sulfur, silver and copper oxide as well as acidified ocher, which was fixed to the ceramic by reduction firing and thus a thin, metallic film left on the objects.

The Islamic luster ceramics can be divided into a polychrome and a monochrome phase. Initially, the potters used a rich palette of colors, but towards the end of the ninth century only a few shades in which the motifs were designed prevailed. The polychrome luster ceramic differs from the later monochrome not only in the variable and rich color scheme, but also in style and iconography. Characteristic is the lack of figurative representations, which cannot be explained by the avoidance of images in Islamic art , as they were quite widespread in other areas of applied and decorative art of the time. Instead, vegetable and geometric motifs were used, which covered the entire surface of the vessels. Symmetrically stylized bouquets of flowers were particularly popular as a decoration. With monochrome luster ceramics, which quickly replaced the polychrome style, figural iconography found its way back into ceramic art, and monochrome outlines of animals and people now adorned the objects.

11th to 14th centuries

From the end of the 10th century, the center of ceramic production, especially the manufacture of chandelier goods, began to increasingly shift towards the west, first to Fatimid Egypt, later to Muslim Spain and from there to other European countries. In Fustat pottery between the tenth and eleventh centuries developed a new type of ceramic, at Jasperware reminiscent stoneware , which probably goes back to Chinese influences, and in particular the three-color ceramic ( Sancai ) of the Tang Dynasty . Ibn Battūta reported about ceramic production in Spain around 1350 that “wonderful gilded pottery” was produced in Málaga , which was exported to distant countries and was ultimately intended to inspire Italian majolica . In Syria, Raqqa became the most important center of chandelier production.

Pottery under the Seljuks

In Persia and Asia Minor, when the Seljuks came to power, ceramic production began to flourish again, but due to the lively construction activity of the patrons, the production of tiles was in the foreground; Tableware and figurative ceramics only played a minor role. Here, too, numerous new techniques for manufacturing and glazing the goods were developed. The Amol or Garrus ware is named after its place of discovery in Āmol , made using the sgraffito or pit melting process ( Champlevé ). The decor of these goods, which are also produced in northern Afghanistan, was partially scraped off so that the dark red shards underneath become visible and a pattern is created.

Building on this manufacturing process, the Minai technique ( Persian “ enamel ” or “ enamel color”) , also known as Haftrang (“seven colors”), developed in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries . First, the color was applied to the clay, then alkaline glazing and fixed and finally fired repeatedly at a very high temperature of sometimes over 1000 ° C. The process enabled an improved delimitation of the colors and was used to produce very detailed and colorful, miniature-like representations of caravans and courtiers, for example, or of literary scenes, especially from the Shāhnāme and the works of Nezāmi . Particularly sophisticated pieces combined the Minai process with the luster.

The centers of Persian pottery production at that time were the cities of Kāschān and Rey , and probably also Golestan and Saveh . The production of Minai goods came to an early end due to the Mongolian devastation from 1221 onwards. The later Lajvardina goods (Persian ' lapis lazuli '), which were still very similar in the production of Minai ceramics, are more abstract and have a much more measured color.

Late period

Among the Ilkhan people , the unglazed, but double- poured Sultanabad ware gained in importance, the design being based on the Chinese celadon ware, but still lagging behind its model; It was not until much later that a comparable product developed in the 18th century with the Gombroon goods. Dotted mammals and birds on a leaf base are a common motif of Sultanabad goods. Ceramic mosaics first developed significantly further under the Rum Seljuks and later under the Timurids .

Due to the Mongol invasion, however, the Chinese influence on Islamic ceramics increased again significantly; Since the fifteenth century, the blue and white porcelain of the Ming dynasty , which in turn was based on the knowledge of the Abbasid potters about blue coloring with cobalt, was imported in large quantities. While the import of this porcelain in the Persian Safavid Empire brought local ceramic production to a virtual standstill, in the Ottoman Empire it had a major impact on the design development of İznik ceramics.

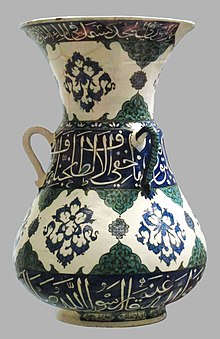

İznik ceramics

The first known products of ceramic manufacture in İznik date from the end of the 15th century and show simple blue underglaze paintings on a white background. In the two hundred years in which ceramic art continued to flourish there, however, numerous other colors were gradually added to the palette: The strong red of the so-called Rhodes goods is also characteristic. The style, which was initially strongly based on Timurid ceramics, soon became much more naturalistic. Especially for the ambitious building projects of Suleyman the Magnificent , including the extensive restoration work carried out on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem around the middle of the 16th century , large quantities of tiles were required, most of which were produced in Iznik. At the beginning of the 18th century, the decline of quality Ottoman ceramics began, which was probably due, among other things, to the change in taste in art and thus the loss of patronage by the mansion: instead of ceramic wall paneling, decorative wood paneling similar to that of the Aleppo room became increasingly fashionable.

Collections of Islamic Ceramics in Europe

The French expedition to Egypt , the British colonial rule in India as well as the increasing processing of the Moorish history of Spain and the romantic rediscovery of the Alhambra as a source of artistic and literary inspiration brought Islamic ceramics increasingly into the European focus in the 19th century. In particular, the high quality İznik ceramics became a coveted collector's item.

The Frenchman Auguste Salzmann and the British Frederick DuCane Godman and George Salting in particular acquired countless ceramic objects that were later exhibited in public museums such as the Musée national de la Renaissance in Écouen Castle and the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London . In Germany, in addition to the collection of the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin , that of the Baden State Museum is of great importance. In addition to historical exhibits, it also contains ceramics by contemporary Muslim artists.

See also

literature

- Anne-Marie Keblow Bernsted: Early Islamic Pottery: Materials and Techniques . Archetype, London 2003, ISBN 978-1-873132-98-2 .

- Richard Ettinghausen , Oleg Grabar , Marilyn Jenkins-Madina: Islamic Art and Architecture, 652–1250 . Yale University Press, London 2001, ISBN 978-0-300-08869-4 .

- Arthur Lane : Early Islamic Pottery: Mesopotamia, Egypt and Persia . Faber and Faber, London 1947.

- Arthur Lane: Later Islamic Pottery: Persia, Syria, Egypt, Turkey . Faber and Faber, London 1971.

- Schoole Mostafawy: Islamic ceramics: from the collection of the Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe . Badisches Landesmuseum, Karlsruhe 2007, ISBN 978-3-88190-437-7 .

- Yves Porter: Le Prince, l'artiste et l'alchimiste - La céramique dans le monde iranien Xe-XVIIe siècles . Hermann, Paris 2011, ISBN 978-2-7056-6624-8 .

- Jean Soustiel: La céramique islamique . Office du livre, Freiburg im Üechtland 1985, ISBN 978-2-7191-0213-8 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ The relative rarity of such descriptions is probably explained by the fact that the workshops tried to protect the secrets of their manufacturing processes from their competitors. See Y. Porter: "Les sources écrites sur les techniques de la céramique dans le monde musulman", in: Jeanne Mouliérac: Céramiques islamiques du monde musulman . Paris: Institut du monde arabe, 1999.

- ↑ The treatise has come down to us in two manuscripts. First publication of the Persian text with German translation in Hellmut Ritter, Julius Ruska, Friedrich Sarre and R. Winderlich, Orientalische Steinbücher und Persische Faience Technique , Istanbuler Mitteilungen 3, 1935. English translation with critical commentary by James W. Allan, “Abū'l-Qāsim's Treatise on Ceramics ", Iran 11 (1973), pp. 111-120.

- ↑ Venitia Porter: Islamic tiles . London: The British Museum Press, 1995, p. 8.

- ↑ Guillermina Joel, Audrey Peli and Sophie Makariou (eds.): Suse, terres cuites islamiques , Paris: Snoeck, 2005.

- ^ Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar and Marilyn Jenkins-Madina, Islamic Art and Architecture, 652–1250 , London: Yale University Press, 2001, p. 62.

- ↑ The technique of glaze had been known since the Sassanid period; see. Jean Soustiel, La céramique islamique , Freiburg im Üechtland: Office du livre, 1985, p. 24.

- ↑ Oliver Watson: Ceramics from Islamic Lands , Thames and Hudson, New York, 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Reflets d'or. D'Orient en Occident, la céramique lustrée, IXe – XVe siècles . Catalog of the exhibition in the Musée national du Moyen Âge , April 9 - September 1, 2008, Paris: RMN, 2008, p. 15.

- ^ John Carswell: Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain and its Impact on the Western World , Chicago, 1985

- ^ Alan Caiger-Smith: Tin-Glaze Pottery in Europe and the Islamic World: The Tradition of 1000 Years in Maiolica, Faience and Delftware . Faber and Faber, London 1973.

- ^ Robert B. Mason, Shine Like the Sun: Luster-Painted and Associated Pottery from the Medieval Middle East , Mazda Publishers, Costa Mesa, 2004, pp. 24-44.

- ^ Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar, Marilyn Jenkins-Madina: Islamic Art and Architecture, 652–1250 , p. 68.

- ↑ Schoole Mostafawy: Islamic Ceramics: from the collection of the National Museum Badischen Karlsruhe , p. 17

- ↑ See for example Christian Ewert : The decorative elements of the chandelier tiles on the mihrab of the main mosque of Qairawan (Tunisia) . In: Madrider Mitteilungen , Vol. 42, 2001, pp. 243-431.

- ↑ The object bears the name of a man who was governor in Egypt for barely a month in 773. However, the dating is not without controversy. See Ralph Pinder-Wilson, George Scanlon: Glass finds from Fustat: 1964-71. In: Journal of Glass Studies , 15, 1973, pp. 12-30.

- ↑ Reflets d'or , pp. 18-19.

- ^ Robert Irwin : Islamic Art . DuMont, Cologne 1998, ISBN 3-7701-4484-8 , p. 178 .

- ↑ Schoole Mostafawy, Islamic Ceramics , pp. 6-7.