Temple mount

| Temple Mount / al-Haram al-Sharif | ||

|---|---|---|

| height | 743 m | |

| location | Jerusalem | |

| Coordinates | 31 ° 46 ′ 35 " N , 35 ° 14 ′ 12" E | |

|

|

||

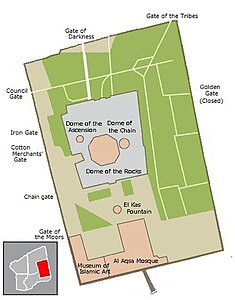

The Temple Mount ( Hebrew הר הבית har habait 'mountain of the house [of God]', Arabic الحرم الشريف al-haram ash-sharif , DMG al-ḥaram aš-šarīf 'the noble sanctuary') is a hill in the southeast of the UNESCO World Heritage Old City of Jerusalem , above the Kidron valley . At its summit is an artificial plateau about 14 hectares in size, in the middle of whichstoodthe Herodian Temple , a successor to the post-exilic Jewish temple, which in turn was built on the foundations of the Solomonic Temple . The Dome of the Rock has stood here since the 7th century AD. On the southern side of the esplanade is the al-Aqsā mosque . The Temple Mount is one of the most controversial sacred places in the world.

Names

Biblical Temple Mount

There are several names in the Hebrew Bible that tradition has equated with the Temple Mount:

- Mount of the House (of God) , Hebrew הר הבית har habait , is the Hebrew name that is translated as "Temple Mount". Within the Hebrew Bible, the formulation occurs in Mi 3.12 EU as the short form of “Mountain of the House of YHWH” in Mi 4.1 EU .

- Arauna's threshing floor ( 2 Sam 24.18-25 EU ). Tennines were in an elevated position and therefore offered themselves as places of worship. The emphasis is on the fact that David determined a previously profane area for the YHWH cult; the older research assumed that this was historically incorrect and that David, on the contrary, found the city temple of the Jebusites and rededicated it.

- Mount Zion . Originally the name of the southeast hill (= City of David ), Zion became partly the name for the northeast hill (= Temple Mount), partly for the city of Jerusalem as a whole and is the theologically filled name of the Temple Mount within the Hebrew Bible (e.g. Joel 4:17 EU ). The name Zion migrated to the southwest hill in Byzantine times.

- Morija (also known in the English spelling: Moriah ): a) The "Land of Morija" ( Hebrew אֶרֶץ הַמֹּרִיָּה æræṣ hammorijjāh ) is the scene of the story of Isaac's bond ( Gen 22.2 EU ); b) the "Mount Morija" ( Hebrew הַר הַמּוֹרִיָּה har hammôrijjāh ) place of the Solomonic temple building ( 2 Chr 3,1 EU ). It is interesting here that the ancient Jewish translators into Greek ( Septuagint ) treated both passages differently: Gen 22.2 "the high country" and 2 Chr 3.1 "Mountain of Amoria." In contrast, Flavius Josephus transcribed the name as ancient Greek Μωριων Mōriōn . The relationship between the two Morija texts in the Book of Genesis and in the Chronicle is unclear; some exegetes (e.g. Hermann Gunkel , Claus Westermann ) suspected that Morija was inserted secondarily into the text of Gen 22 in order to relate the story of Isaac's bond with the Jerusalem Temple Mount. Detlef Jericke sums up the view of today's historical-critical biblical studies: “It cannot be proven that Morija was a place or terrain name in Old Testament times. Rather, it can be assumed that it is a matter of literary education. ”Morija's identification with the Temple Mount has been established since early Jewish times (see: Josephus) and is also assumed by the Midrashim and Targumim .

As Yaron Eliav and Rachel Elior have pointed out, the term Temple Mount did not become common until after the temple was destroyed by Roman soldiers in AD 70.

Temple Mount in Islamic Reception

The following are the names of the platform or esplanade , which was created by Herod's construction work and which is identical to the Haram:

- Maqdi's "sanctuary" was the entire esplanade in early Islamic times, as well as Bait al-Maqdis , a loan from the Aramaic Bet Maqdescha , "house of the sanctuary", and Masjid Bait al-Maqdis, "mosque of the house of the sanctuary."

- al-Masjid al-Aqsa "the distant place of worship" is the destination of the nightly heavenly journey of the Prophet Mohammed in the Koran . This designation has been the common name for the temple square since the time of the Omayyads and is currently gaining popularity. So defined e.g. B. the Jordanian-Palestinian agreement for the joint defense of al-Masjid al-Aqsa (March 31, 2103) this as an area of 144 dunams (14.4 ha), "including the Qibli mosque of al-Aqsa, the mosque of the Dome of the Rock and all associated mosques, buildings, walls, courtyards, associated areas above and below the ground and the Waqf properties associated with al-Masjid al-Aqsa , with their surroundings or with their pilgrims. "

- al-Haram al-Sharif , the “raised, demarcated sacred area” is a comparatively more recent name. It came up after the conquest of Jerusalem by the Crusaders in the 13th century and was used almost officially for the Esplanade with its Muslim buildings in the Peace of Jaffa in 1229. In the 19th and 20th centuries, this was the predominant Arabic term in the language used by the Jerusalem population, by the Ottoman authorities and, consequently, also in the specialist literature emerging during this period. In terms of religious law, however, it is questionable whether the Jerusalem holy place is a haram . Ibn Taimiya turned against this usage as early as the 14th century .

Political explosiveness of the name

The terms Temple Mount and al-Haram al-Sharif are not neutral; they already express a certain valuation of the holy place. Many commentators criticized the fact that a UNESCO resolution introduced by Arab states in October 2016 dealt with the endangerment of the historical building fabric of the holy place and consistently used the name Al-Aqṣa Mosque / Al-Ḥaram Al-Sharif . "Temple denial is worse than Holocaust denial," said archaeologist Gabriel Barkay , who was involved in the Temple Mount Sifting Project at the time. "According to Israeli government circles, Unesco has thus denied the historical connection between Judaism and the Temple Mount," remarked Carlo Strenger in an article for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung .

Since there is no neutral name for the site, the double designation “Temple Mount / al-Haram al-Sharif” ( Temple Mount / Al-Haram al-Sharif, TM / HS ) is used in scientific literature .

Religious meaning

In Judaism

The Deuteronomy emphasizes that there can be only one legitimate place of worship for Israel; the Samuel and Kings books specify that this place of worship is the temple in Jerusalem. That the temple is on a holy mountain does not appear in this conception, but it does in the psalms and the books of the prophets.

In 2 Sam 7 King David expresses the wish, now that he himself lives in a palace, to build a “house” for the ark of YHWH . The prophet Natan then announced the divine answer that, conversely, YHWH would build a “house” for David, namely a permanent royal dynasty. Not David, but only his son ( Solomon ) will build the temple.

The history of how the chronicler ( 2 Chr 3,1 EU ) linked different strands of tradition became significant :

Solomon builds the temple

- in Jerusalem, on Mount Moriah (geographical definition connected with the story of the binding of Isaac , Gen. 22);

- where YHWH appeared to his father David ( theophany );

- at the place that David had designated (Solomon follows orders from his royal father to build the temple);

- on the threshing floor of the Jebusite Arauna (connected with the cult legend that an epidemic ended when David built an altar here, 2 Sam 24).

Scriptures from the Second Temple period described more precisely that the temple house was in the middle of an architectural complex; there was a graduated system of religious significance for these courtyards and galleries. At the same time, the entire architectural complex could also be called a “temple”. The 1st Book of Maccabees has a special position , which repeatedly emphasizes the temple mountain as a religiously significant place ( 1 Makk 4.46 EU ). In Flavius Josephus first met the idea that the environment of the temple complex as Temenos have a kind of holiness. This conception is fully developed in the Mishnah : according to Mishnah Middot I, 1–3, the Temple Mount had five gates that were guarded by Levites and a “man over the Temple Mount” who controlled them. Mishnah Bikkurim III, 4 describes the procession with the first fruits to the temple; the Temple Mount is one stop here before the pageant reaches the temple forecourt. Special rules apply to entering the Temple Mount: “Do not approach the Temple Mount with your staff, with your shoes, your money belt or with dust on your feet. And don't make it a shortcut, and even less should you spit it out. ”All of these details give the impression of being memories of the Second Temple; according to Yaron Z. Eliav, however, the concept of “Temple Mount” comes from the world of rabbis.

The destruction of both temples 655 years apart, both of which took place on Av . 9 after the Mishnah , are central events in Jewish history . The rebuilding of the temple in Jerusalem is the concern of the eighteen petitioner .

After the destruction of the year 70 and after attempts to rebuild the temple failed, Jews visited the Temple Mount even though they were not allowed to live in Aelia Capitolina . There were apparently liturgies for these visits, although the details are no longer known. Within the rubble landscape, a towering piece of natural rock gained special significance. This is the cornerstone of creation, on which the ark of the covenant stood in the holy of holies ( Hebrew אבן השתייה 'ævæn ha-štijjā ). "After the continuation of the ark, a stone remained there since the days of the first prophets, and it was called the foundation (cf. Zech 9,3), its height above the earth was three fingers ..." The parallel in the Tosefta interprets this rock as Navel of the world . According to Eliav, a process becomes visible here that religiously upgraded the temple mountain and the sacred rock, regardless of the destroyed temple buildings. According to later Talmudic legend, God took the earth from which he formed Adam at this point . Here were Adam, later Cain , Abel , Melchizedek and Noah their sacrifices offered.

The western wall or wailing wall is part of the western perimeter wall of the Herodian esplanade. Many Jews pray there. It is common to leave prayer slips / petitions in the cracks in the wall.

The Liberal Judaism modernized the traditional services, including by removing items from it, the symbolic representation of the sacrifices should be replaced in the temple ( Musaf -Gebet). Because a new building of the Jerusalem temple and a resumption of animal sacrifices was not a goal for reformers like Abraham Geiger . When the first US reform congregation was founded in Charleston in 1825, this new direction was formulated as follows: “This country is our Palestine, this city is our Jerusalem, this place of worship is our temple.” That is why synagogues are called temples in liberal Judaism.

Orthodox and conservative Jews, on the other hand, cling to the importance of the Temple Mount. Samson Raphael Hirsch wrote: “Even if the temple lies in ruins and the Zijaunsberg , which God has chosen to be a sanctuary, is desolate , its meaning for us remains eternal, and our duty is eternal: to preserve respectful respect for it. Even today you are not allowed to step carelessly to that holy place, not with stick and shoes and covered with dust, ... even today only step there to step on the ground of the divine sanctuary and to give space to your feelings. ”In the present one is only allowed go to the wall ("bis ans חיל"). Hirsch formulated these principles in 1889, at a time when the Haram al-Sharif could only be entered by non-Muslims in exceptional cases.

For centuries, the question of whether a new temple should be built and the sacrificial service resumed had at most been a theoretical question in Judaism, and Zwi Hirsch Kalischer (1796–1874) first suggested sacrificing a Passover lamb within the framework of such mental games . The Chafetz Chaiim recommended that his followers study the Mishnah (Seder Kodaschim) sacrificial laws in order to be prepared for the onset of salvation. In 1921 Rabbi Zwi Jehuda Kook founded the Torat-Kohanim-Yeshiva ( Yeshiva for the study of the priestly laws) in the old city of Jerusalem.

Lechi , a Jewish nationalist, secular underground movement, brought in a new aspect , which in its manifesto “Principles of Renewal” (1940/41) formulated the last of its goals: “Construction of the Third Temple as a symbol of the new era of total redemption.”

In Christianity

In the Jesus tradition there are various positive references by Jesus to the temple and its holiness, e.g. B. Jesus sent a person he had healed to the temple so that a priest could perform the cleansing ritual there with him (Mk 1.40-44).

- In the temple word (Mk 14,58, Joh 2,19), which probably goes back to the historical Jesus of Nazareth, he announces that he wants to tear down the temple and replace it with an eschatological temple that was not made by hand. So Jesus was interested in the temple and cared about it.

- The temple action ("temple cleansing") was a spectacular call to repentance. Jesus brought the sacrificial cult to a standstill for a short time and pointed to a new service in the “House of Prayer”. This action is widely believed to be a historic event in the life of Jesus, but it is unclear on the one hand what extent the action was - in view of the known strict guarding of the esplanade by the temple police - and on the other hand what interpretation Jesus himself gave of this action.

Among the authors of the New Testament, it was especially the author of the Lukan double works ( Gospel of Luke and Acts of the Apostles ) who emphasized the temple visits by Jesus, his family and his disciples. The apostles continued to meet in the courtyards of the temple after Easter ( Acts 5:12 EU ). Paul of Tarsus was captured here because other temple goers claimed that he had brought a gentile into the inner area of the temple, which was only reserved for Jews ( Acts 21: 27–30 EU ). Luke emphasized that the accusation that Christians are hostile to the temple is unfounded.

The crucifixion of Jesus and the destruction of the temple - two historical events that are around 40 years apart - were causally linked by authors of the early church and on the subject of Christian theology of history: the rejection of Jesus by the majority of the Jewish people brought about the end of the temple cult ; the church is now the new people of God ( substitution theology ). These considerations have starting points in the New Testament, especially in the Gospel according to Matthew ; the difference lies in the fact that for the evangelist the Jewish war, his own present and the expected end of the world in the near future coincided and the question of the further development of Judaism and the temple cult therefore did not arise. That was different for the theologians of the early church: when Emperor Julian allowed the rebuilding of the Jerusalem temple in 363, this project put the Christian self-image into question, just as Christian observers felt confirmed by the failure of these plans. Behind the theological interpretations of the Christian authors who report on it ( Gregor von Nazianz , Ephraim von Nisibis ), the historical processes are hardly recognizable. John Chrysostom put it in a nutshell: “Christ founded the Church and no one is able to destroy it; he destroyed the temple and nobody can rebuild it. "

Christianity does not expect a new temple to be built, because Jesus Christ has become the place of reconciliation (Rev 21:22). But it can affirm Jewish temple hopes in an eschatological context.

In Islam

Islam sees itself in continuity with the older religions Judaism and Christianity. Thus wrote the Jerusalem Qadi and historian Mujir ad-Din al-ʿUlaymi (مجير الدين العليمي) in the 15th century with reference to older tradition: “After David had built many cities and the situation of the children of Israel had improved, he wished to build Bajt al-Maqdis (the house of the sanctuary) and a dome over the one sanctified by God To erect rocks in Aelia , "and:" Solomon built Masjid Bajt al-Maqdis on behalf of his father David. "

Jerusalem was the first direction of prayer of the Muslims and, according to the Koran, the destination of the heavenly journey of the Prophet Muhammad: “Praise be to him who with his servant (i.e. Mohammed) at night from the holy place of worship (in Mecca) to the distant place of worship (in Jerusalem), whose surroundings we have blessed traveled to let him see some of our signs (w. so that we let him see some of our signs)! He (ie God) is the one who hears and sees (everything). ”(Sura 17,1) Mujīr al-Dīn interpreted this Quranic verse in such a way that God had transferred the Prophet Mohammed from Mecca to Jerusalem. In agreement with other commentators, he saw Jerusalem doubly blessed:

- in the past, as the place of activity of earlier prophets,

- in the future, as a place where people gather on Judgment Day .

Mujir ad-Din evaluated several sources for his theology of the shrine of Jerusalem, which he related to each other. So a picture of the past emerged that made David and Solomon appear less as temple founders than as temple renovators: For the first temple was built by angels, this was renewed by Adam , then by Shem, the son of Noah, then by the patriarch Jacob . Thereafter, Mujir ad-Din classified David and Solomon.

Since heaven and earth are particularly close in Masjid Bait al-Maqdis and angels ascended and descended here, prayers are particularly effective in this place. One prayer in Jerusalem, the prophet is quoted, outweighs a thousand prayers elsewhere. Whoever prayed in Jerusalem would be forgiven of all sins and return to the state of innocence. It is particularly advisable to start the pilgrimage to Mecca in Jerusalem.

The Muslim tradition that the angels and then Adam built a temple on the Temple Mount plays a role in the current political conflict. The Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Muhammad Ahmad Hussein , interpreted it in 2015 to mean that there has been a mosque here since the creation of the world - and not a Jewish temple.

history

First and Second Jewish Temples

According to Biblical tradition, the First Temple was built under King Solomon . Even if the hypothesis of a great Davidic-Solomonic empire is no longer shared by many experts and a Solomon who ruled only a small, sparsely populated and economically weak state did not have the means to build a magnificent temple complex: No later Jerusalem king wrote this up Build too. According to Israel Finkelstein, this suggests that the temple goes back to Solomon and was expanded by later kings of his dynasty, so that the structure described in 1 Kings 6-7 was created.

This temple was built in 586 BC. Destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar II and the Babylonians . From 521 BC. BC - after the end of the Babylonian captivity - the temple was built with Persian help and 516 BC. Completed. Jewish tradition calls this the "Second Temple". There is "absolutely nothing left of both temples and their sacred implements."

New Herodian temple

The Second Temple had become dilapidated over time. Herod , the Jewish client king of Judea under Roman rule, therefore planned a new temple, which next to the port of Caesarea was his most ambitious building project. Basically, this building could be called the “Third Temple”, as it was by no means just repair work on the Second Temple. However, it is customary to also address the Herodian Temple as the Second Temple and therefore to let the "period of the Second Temple" (a standard epoch designation used by Israeli historians) end in the year 70 AD.

Completion dragged on beyond the reign of Herod until almost the beginning of the Jewish War . According to the literary descriptions ( Josephus , Mishna Middot ), the actual temple house was a conservative building that probably looked relatively similar to the previous building erected in Persian times. The interior of the temple was divided into three parts; A vestibule was followed by the room in which the most important cult utensils ( menorah , showbread table ) were set up, and behind it the Holy of Holies, a completely empty room that was hidden from view and the high priest was only allowed to enter once a year. This central temple area was surrounded by adjoining rooms on three sides and had an upper floor above the vestibule, saints and holy of holies, from where craftsmen could be roped down into the temple rooms through holes in the floor in order to do the necessary work.

The temple house was surrounded by a series of courtyards, the so-called forecourt of the women was de facto the place to which Jewish pilgrims came on their temple visits and from where they could observe the temple cult of the priests. The outer temple forecourt is one of the largest temple areas in the ancient world; it was roughly trapezoidal and had an area of over 14 ha. The external dimensions were:

- West side: 485 m;

- East side: 470 m;

- North side: 315 m;

- South side: 280 m.

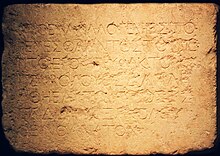

The courtyard was bordered on three sides by colonnades, and in the south there was a stoa basilica. A balustrade (soreg) was drawn around the central area with the temple house and courtyards, marking the boundary up to which non-Jews could stay on the Temple Mount. Two Greek warning signs from this balustrade have been preserved in the original and represent the most important material remains of the Herodian temple itself (the wailing wall is part of the surrounding wall). With the large esplanade, its enclosing walls and its buildings, Herod created a new, artificial topography that made a great impression on his contemporaries: it dominated the cityscape of Jerusalem (as you can see on the Holyland model, see photo), and the esplanade remained existed as a type of man-made mountain when the temple burned down in 70.

During the Jewish War , the temple and its surroundings were fiercely fought over. According to Josephus, there was a council of war in the Roman camp before the city was captured to discuss the fate of the temple. Some commanders were of the opinion that, since the temple was being defended by insurgents, it should be treated as a fortress and destroyed; Titus, on the other hand, wanted, according to Josephus, to keep this “magnificent building”. The arson of a single soldier led to the destruction of the temple. With this version, however, it is inexplicable how the Romans were able to steal golden utensils and easily combustible textiles from the temple - which Josephus also reports. In any case, Titus then ordered the razing of the city and the temple. On the triumphal procession in Rome temple devices were shown as well as display scaffolds with pictures of the temple fire.

Use of the Temple Mount in Roman and Byzantine times

The Münzkabinett of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin owns a bronze coin minted in Aelia Capitolina between 130 and 138 AD, which shows a tank bust of the Emperor Hadrian on the obverse , but a two-pillar temple front with the Capitoline triad : Iupiter sitting, after turned left and framed by the two standing goddesses Minerva and Iuno . It is generally assumed that this coin depicts a temple of Hadrian in the colonial city he founded, which is also mentioned by Cassius Dio .

However, there is no consensus of research on the question of where this temple was, whether on the temple grounds or in the area of the forum of the newly created city. Since archaeological excavations on the Temple Mount are permanently not possible, one tries to clarify with the help of historical sources how this area was built in Roman and Byzantine times:

The formulation in Cassius Dio, ancient Greek καὶ ἐς τὸν τοῦ ναοῦ τοῦ θεοῦ τόπον kaì es tòn toũ naoũ toũ theoũ tópon , allows two interpretations, which can be reproduced well in German:

- "... and in the place of the temple of God he (Hadrian) built a new temple for Jupiter";

- "... and instead of the temple of God he built a new temple for Jupiter".

The first understanding of the text was almost universally represented in older research and is still in support today. It implies that the Temple Mount was central to the city of Aelia.

The second understanding of the text means that Cassius Dio cannot find any information about the location of the temple. It may have been anywhere in the city. The follow-up question is: what function did the Temple Square have for the Hadrianic city in this case? Yoram Tsafrir e.g. B. assumed that the Temple Mount was an open area used by the pagan cult without any actual temple construction.

The assessment is made even more difficult by the fact that the text by Cassius Dio is only available as an excerpt by John Xiphilinos (11th century), so that the formulation contains his view of what happened; but this Christian monk shows in his adaptation of Cassius Dio the anti-Jewish tendency to stylize the Bar Kochba uprising as a struggle between Hadrian and the Jewish religion.

In the Itinerarium Burdigalense (333 AD) there is a note that there was a sanctuary ( aedes ) and two statues of Hadrian on the Temple Mount . With aedes while also still remaining of the destroyed Jewish temple can be meant.

Two church writers , Sozomenus and Theodoret , write that Emperor Julian allowed the Jews to rebuild their temple and, as a first measure, the Jews removed the foundations of the temple. It is often assumed that these were the remaining ruins of the Jewish temple that were to be replaced by a new building. Michael Avi-Yonah assumed that the Temple of Jupiter on the Temple Mount had fallen into ruin since Constantinian times, which had been cleared away by the Jews. However, it contradicts Julian's religious policy to agree to the destruction of a pagan temple, and therefore his surrender of the Temple Mount for the Jewish cult can also be interpreted as meaning that there was no Roman temple there.

Jerome saw a statue of Jupiter and an equestrian statue of Hadrian on the Temple Mount in the late 4th / early 5th century. Max Küchler interprets the statues mentioned by several ancient authors as follows: Aelia's religious center was located in the area of the forum. “The two imperial statues, on the other hand, signaled the location of the destroyed Jewish. At the center, the imperial power of Rome. ”When Jerusalem rose to become a Christian pilgrimage destination in the post-Constantine period, the Temple Mount was deliberately left as a ruin (various sources mention stone robbery and agriculture here), because it was possible to visibly demonstrate the destruction of Jewish hopes and also believed the end times will only come when “no stone stands on top of another” from the Jewish temple (cf. Mk 13,5) - until then, as the ruins show, there was still a time limit.

New arguments were made in the 1990s for a temple of Jupiter on the Temple Mount: Two 7th century Christian authors who lived in Jerusalem casually referred to the Temple Mount (possibly taking up the everyday language of the Jerusalem population) as the Capitolium . On the other hand, it can be objected that all older Christian sources do not know these designations and that Capitolium can be an attribution from Byzantine and early Islamic times.

Conclusion: As of 2019 there is no evidence of a temple of the Capitoline Triassic on the Temple Mount, but there is a probability that emperor and Jupiter statues were erected there and ritual acts took place there.

Islamic development: al-Masjid al-Aqsa

The entire esplanade is considered a mosque in the Islamic understanding. The rocky dome in the middle of the square, venerated by Jews, was only built over by an octagon with a golden dome (“ Dome of the Rock ”) under Caliph Abd al-Malik . Originally decorated with mosaics, floral motifs on a gold background and not with blue tiles, this sanctuary is the oldest building in the Islamic world. Started in 684/689, completed in 691/692, the construction did not experience any major damage or alterations.

Architecturally, the Dome of the Rock follows the tradition of Christian central buildings, including the Kathisma Church between Jerusalem and Bethlehem, the Theotokos Church on Mount Garizim , the Cathedral of Bosra and the Church of St. George in Ezra. The dome of the Dome of the Rock (diameter 20.44 m) and the dome of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (20.46 m) correspond in a striking way, so that the Church of the Holy Sepulcher was probably a model and model in this regard. Overall, the Dome of the Rock, so the thesis of Shlomo Dov Goitein , can be seen as the “answer of early Islam. Congregation on their christ. Environment and its church landscape ”.

Various sources indicate that Jews saw the heir to the Temple of Solomon in the Dome of the Rock, if not the hoped-for reconstruction, and took an active part in the construction work. Later Jews were employed in the maintenance of the sanctuary, that is, they cleaned the building, made glass lamps and lit them. “Open construction took place… the construction of the Dome of the Rock under the auspices of a narrow Jewish-Islam. Symbiosis, the early Islam. The congregation sought its own identity in line with biblical traditions, and it is therefore not surprising if ... also the sacristan services in the Dome of the Rock ... in Jewish. With the Abbassid control of Jerusalem (middle of the 8th century), this tolerant time ended and Jews were no longer given access to the haram.

Templum Domini of the Crusaders

After they had conquered Jerusalem in the summer of 1099, the Crusaders claimed the Dome of the Rock under the name Templum Domini , "Temple of the Lord" for the Christian cult. It was even upgraded to the second most important pilgrimage site in Christianity (after the Church of the Holy Sepulcher ).

This was a new development because the Christian pilgrimage literature of the 7th to 11th centuries had ignored the Muslim construction work on the Haram. All that was said in general was that the remains of the destroyed Jewish temple could be seen there. According to Sylvia Schein, the Christian use of the haram building as a church and palace had pragmatic reasons: after the conquest there was no money for large building projects, and so the conquered, very representative Muslim buildings were used for their own purposes. According to Heribert Busse , on the other hand, it was a memory of Mary on the haram ( Miḥrab Maryam / Mahd ʿĪsa ), which the Crusaders picked up and which became a point of reference for their own devotion to Mary.

Godfrey of Bouillon installed secular canons on the Dome of the Rock ; later (before 1136) it became a collegiate monastery of regulated Augustinian canons . Her prior Achard d'Arrouaise wrote a poem with the title Tractatus super Templum Domini , in which he gave the official interpretation of the Christian used Dome of the Rock: he reported the history of the Jewish temple from Solomon to the destruction by Titus according to the Bible and after Flavius Josephus . According to this, a Christian ruler ( Constantine , Helena , Justinian or Herakleios ) built the Dome of the Rock, which is therefore a Christian cult building that the Saracens used for other purposes. Now the Dome of the Rock attracted Old and New Testament traditions; In some cases, these were substances that had already been commemorated by Muslims in the haram: Adam's tomb, the navel of the world , Abraham's sacrifice, Jacob's dream in Bet-El, David's repentance, the proclamation to Zacharias, the childhood of Mary and the cleansing of the temple of Jesus.

The construction work remained limited due to the lack of European lands for the monastery. The sacred rock was covered with marble slabs to prevent pilgrims from taking chunks of rock with them. A high altar was built over it. In 1141 Alberich von Ostia consecrated the building as St. Mary's Church. A wrought-iron lattice and a candelabra have been preserved, both of which are now in the Haram Museum.

When Godfrey of Bouillon became the governor of the Holy Sepulcher , he designated the al-Aqsa mosque (referred to as the palace or temple of Solomon, Palatium / Templum Salomonis ) as the palace of his dynasty. In 1118/19 Hugues de Payns founded the Knights Templar in a side wing ; In 1120, the order took over the entire building as the royal family moved to the citadel. During the Muslim reconquest in 1187, Saladin had the alterations made during the crusader era on the haram largely removed.

Haram al-Sharif in the 19th and early 20th centuries

Until the end of the Ottoman Empire, the Temple Mount was a purely Muslim site. Jews were not only prohibited from entering the haram, they were also temporarily not allowed to stay near it or look at it up close.

As far as is known, the architect Frederick Catherwood was the first European to make drawings of the Haram and Dome of the Rock in 1833. Between 1865 and 1869, Charles Wilson and Charles Warren conducted a survey that documented many details of the enclosing walls and underground structures. It was not until 1885 that some high-ranking non-Muslim guests were allowed to visit the haram: the Crown Prince of Belgium (later Leopold II ), the Austrian Emperor, the British heir to the throne and Sir Moses Montefiore . Knowledge of the Islamic architecture of the Haram was promoted in the last years of the Ottoman Empire by Keppel Archibald Cameron Creswell (Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa) and Max van Berchem (Arabic inscriptions).

The British Mandate Government made no changes to the Muslim control of the Temple Mount, but in 1917 non-Muslims were allowed access, but only during certain opening times and against payment of an entrance fee. After the unrest of 1929, Jews were no longer allowed to enter the haram.

During renovation work between 1923 and 1942, the al-Aqsa mosque was completely restored in the neo-Abbasid style, around two thirds of the historical building fabric was lost as a result. As part of the renovation of al-Aqsa after the earthquake of 1927, Robert Hamilton, as director of the antiquities administration of the British Mandate Government, examined the area in detail and created several sections. In doing so, he came across mosaic floors that possibly dated to the Byzantine period and that could speak for the existence of a church on the Temple Mount that has not been documented in literature or that belonged to early Islamic buildings. However, Hamilton did not document these findings more precisely, and so one of the rare opportunities for archaeological exploration of the Temple Mount was wasted.

During the Palestine War (1948) the buildings on the Temple Mount were partially destroyed by shells and rebuilt in the following years with technical and financial help from Jordan , Saudi Arabia and Egypt . Under Jordanian administration, Jews were denied access to East Jerusalem, including the Temple Mount (with regard to the Temple Mount, Jordan continued the practice of the British Mandate Government), but Christians had the opportunity to tour the Esplanade.

Six Day War

Shortly after the beginning of the Six Day War , Israeli troops took over the old city of Jerusalem. On June 7, 1967, Mordechai Gur, the commander of a paratrooper unit, reported: “The Temple Mount is in our hands!” Jordanian snipers had taken up position on the minaret of the al-Aqsa mosque; apart from this minaret, there was hardly any damage on the Temple Mount. (Anwar al-Khatib, the highest Jordanian government representative in Jerusalem, had tried unsuccessfully to prevent the military from using the minaret.) Uzi Narkiss, as the commander of the Israeli armed forces, forbade soldiers from entering the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque and had guards stationed there. His order was apparently disregarded. The chief military rabbi Schlomo Goren accompanied the paratrooper unit that took the Temple Mount and entered the Dome of the Rock to blow the shofar . There he met Uzi Narkiss. As he reported in retrospect, Goren spoke to him at the time and suggested that he take the opportunity and blow up the Dome of the Rock. Narkiss then threatened him with arrest. Well-known personalities visited the shrines and the Israeli flag was briefly hoisted on the Dome of the Rock. Moshe Dajan had the flag removed immediately, ordered the military to withdraw from the Temple Mount and declared that all holy sites in Jerusalem could be visited immediately by members of all religions. The Israeli military then set up a checkpoint at the southwest entrance to Temple Square. On June 17, 1967, Dayan met with the religious authorities of the Jerusalem Muslims in the al-Aqsa mosque and announced the regulations of the status quo (see below).

Goren now assumed a leading role among the rabbis, who (in contrast to the chief rabbinate) spoke out in favor of prayers on the Temple Mount and identified areas there that were outside the former temple house and the inner temple courtyards and which therefore it is not taboo to enter. In this context, Rabbi Zerach Warhaftig , the minister for religious affairs, stated that the whole Temple Mount was "Jewish property" because King David had bought it.

The State of Israel redesigned the immediate vicinity of the Temple Mount after 1967, first by demolishing the Mughrabi district, creating the new Western Wall Plaza, and then through extensive archaeological work along the southern and western perimeter walls. The Jewish-Israeli public was invited to use these rooms close to the Temple Mount: culturally by viewing archaeological findings, and religiously by praying at the Western Wall (the Western Wall Plaza is also the site of state memorials and military ceremonies).

Todays situation

status quo

The status quo refers to the following regulations that apply after Israel gained control of the Old City of Jerusalem and the Temple Mount in the Six Day War:

- Israel controls access to the Temple Mount.

- The Jerusalem Waqf Authority manages the area and the holy places. In 1984 the Israeli government withdrew the Western Wall (which actually belonged to the Temple Mount as part of the outer wall) from the administration of the Waqf and declared it state property.

- Jordan is funding this Waqf agency; The Hashemite royal family feels it is their responsibility to represent compliance with the status quo vis-à-vis the Israeli government.

- Defense Minister Moshe Dayan ordered that Jews enter the Temple Mount but not pray there; the chief rabbinate supported this regulation, which in 1967 was supposed to prevent the Middle East conflict from developing into a religious conflict.

"This status quo from 1967 was also expressed in the Israeli-Jordanian peace treaty of 1994 and is still used today as a reference when it comes to changes - e.g. responsibilities or visiting rights - on the Temple Mount."

The Israeli government refrains from consistently enforcing Israeli law on the Temple Mount (which it claims together with East Jerusalem as Israeli state territory, but this is not recognized internationally). In the case of the Temple Mount, two Israeli laws are particularly relevant:

- Holy Places Conservation Act (1967),

- Antiquities Act (1978); Since 1967 the Temple Mount has also had the status of an archaeological site.

The administrators of the site after 1967 were moderate, Jordan-appointed Palestinians who generally kept to agreements with the Israeli police. The passive acceptance of some of the regulations by these Palestinians and Jordanians enabled Israel to create the impression that the Temple Mount is under its state sovereignty:

- Expropriation of the al-Madrasa al-Tankiziyya building where the police station is located;

- Claiming the keys and thus control of the Mughrabi gate;

- Sole responsibility for security and order on the site;

- Access restrictions for security reasons;

- Coordination of admission modalities, opening times and visits by VIPs;

- Prosecuting crimes committed on the Temple Mount under Israeli law;

- Partial enforcement of Israeli building codes.

In the course of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the Waqf came increasingly under the influence of the Islamic movement in Israel. He sees himself less as a religious service provider waiting for a holy place, but more as a political actor.

From a Palestinian point of view, there is an Israeli agenda to divide the holy place between Jews and Muslims along the lines of Hebron; In 2001, Israel announced that the open spaces and green spaces on the Haram were to become the Israeli National Park in future, which would limit the control of the Waqf authority to the buildings.

Access and access restrictions

Access to the Temple Mount is possible for Muslims via eight gates on the north and west sides of the complex. All gates are monitored by Israeli police officers and Waqf employees. People of different faiths are only allowed to enter via the Mughrabi Bridge and the Moroccan Gate at the Western Wall . Entry is only possible after security checks outside of prayer times and only from Saturday to Thursday.

Situation of the Muslims

After the First Intifada , Israeli police imposed access restrictions on Muslims who did not live in Jerusalem.

Access restrictions have been in force since 2003 when the security situation is tense and according to information from the Israeli secret service. The usual entry criterion is the age of men (over 40 or 45 years); there are usually no restrictions for women.

Situation of the non-Muslims

Until the Second Intifada , tourists were allowed to visit the al-Aqsa Mosque, the Dome of the Rock and the Islamic Museum for a fee. Between 2000 and 2003, the Waqf categorically denied non-Muslims access to the haram. Since 2003 it has been allowed to visit the haram again, but not to enter the building. It is prohibited to bring religious books and cult objects of any kind (such as Torah scrolls) and to hold prayers from other religions. For security reasons, Jews are only allowed in in small groups and often with supervision. In view of these restrictions, the organization HALIBA advocates free access for Jews to the Temple Mount.

The Israeli chief rabbinate issued a ban on entering the Temple Mount in 1967 because the required state of ritual purity can no longer be achieved in the present. Now part of the Herodian temple forecourt (up to the balustrade) was also accessible to non-Jews. So it seemed possible to show a course on the Temple Mount on which Jewish visitors could move without entering the areas where the temple house and the inner courtyards were once located. Schlomo Goren in particular dealt intensively with this topic and in 1992 drafted a plan of the Temple Mount that identified a 110 m wide strip in the south of the Esplanade as a "safe" zone in which Jews could stay, pray and build a synagogue. Goren did not mention that the al-Aqsa mosque is currently located in this strip.

What was practiced by only a small minority of religious Jews in the 1990s has since gained popularity in the national religious spectrum of the Israeli population. This development is accompanied by a discussion process within the rabbinate, where several rabbis of different origins are now speaking out in favor of Jews visiting the Temple Mount. Religious significance is ascribed to the tour of the esplanade (and not to standing, touching or prostrating). As Sarina Chen explains, Hasidism has the idea that wandering can have a redeeming effect; This traditional concept was combined with the modern concept of the protest march among the Temple Mount activists. In 2014, the Sephardic Chief Rabbi Yitzchak Josef reaffirmed the religious ban on entering the Temple Mount: “Jews are not allowed to go to the Temple Mount and provoke the Arab terrorists. This must stop ... only in this way will the blood of the people of Israel be stopped. "

Modifications and repairs

The enforcement of Israeli building law on the Temple Mount is not done consistently but selectively. The Waqf authority (successfully) applied for exemption from the import tax for building materials and carpets that it obtained from abroad, on the other hand the Waqf authority also carried out renovation measures without having these approved. The Temple Mount Faithful sued these arrangements in the Supreme Court in the 1980s.

During archaeological excavations at the Warren Gate, one of the ancient entrances to the Herodian Temple, Rabbi Jehuda Getz, responsible for the Western Wall, cleared the entrance to the tunnel that leads to the Sabil Qaitbai well (Cistern 21) on the Temple Mount in 1981. This fountain is only 80 meters from the Dome of the Rock. A scuffle broke out between the workers overseen by Getz and Waqf employees. The Israeli government had this underground access to the haram sealed.

An arrangement that failed shortly before the goal was the agreement in 1996 that the Waqf authorities would accept the opening of the Western Wall tunnel and in exchange for it would be allowed to prepare Solomon's stables as a mosque ( Marwani Mosque ). The Israeli side finally decided against it, arguing that the tunnel was not part of the Temple Mount, and therefore the Waqf authority had no say there: the opening of the tunnel was simply communicated to the Waqf authority.

In 1998, the Waqf had started restoration work in Solomon's stables. One of the motives was to forestall a synagogue in the south of the Temple Mount; The experience of the Western Wall Tunnel had shown that an underground room would be suitable for this.

The peculiarity of this 6500 square meter room is that it is located in the southeast corner of the Haram and could in principle also be accessed from the outside through two locked gates in the city wall, but could only be entered from the esplanade through a narrow, 1 meter wide entrance .

Without archaeological supervision, a new wide ramp was created as access for the Marwani Mosque and the excavation was tipped into the Kidron Valley by truck. In particular, the archaeologist Gabriel Barkay , Bar-Ilan University , advocated retrospectively examining the excavated soil and thus limiting the damage. From 2004 to 2017 the Temple Mount Sifting Project dealt with the investigation of the excavation, whereby interesting small finds were repeatedly presented in the media. However, many archaeologists expressed their skepticism: "Because the finds do not come from their correct archaeological context and the excavation has been relocated at least twice since the mosque was renovated, the process lacks scientific value." ( Katharina Galor )

Israeli archaeologists also feared that work on the Marwani Mosque would destabilize the Temple Mount and the Western Wall. In the fall of 2002 a bump of about 70 cm was found on the south wall. It was feared that the deformed part of the wall would collapse. Since the Waqf did not allow a detailed Israeli inspection, an agreement was reached between Israel and the Waqf authorities to have the wall examined by a group of Jordanian engineers (October 2012). According to their report, the necessary repairs were carried out in mid-2013.

On October 10, 2019, Israeli police cleared a makeshift mosque in the Golden Gate . They removed and confiscated prayer rugs, cabinets with religious books, and a wooden prayer niche. The gate is a building with a hall and courtyards. According to the Israeli authorities, the Muslims set up a mosque there in the weeks before the eviction, thereby violating the status quo. This means that, according to Israeli information, in the reference year 1967 the Golden Gate was not a prayer room but a storage room; the use of the gatehouse as a mosque has been documented in the sources since the 11th century.

Groups aiming to build the Third Temple

According to a 2012 poll, only 17 percent of Israel's Jewish population would like the Third Temple to be built. But 52 percent want Jews to be able to offer prayers on the Temple Mount (43 percent of secular and 92 percent of religious Jewish Israelis).

- Rabbi Yisrael Ariel and the Temple Institute he founded . Among other things, the institute is dedicated to the training of Jewish priests ( Kohanim ) in questions of the sacrificial cult and has carried out a reenactment of the Passover sacrifice as part of this educational work since the 2000s . The request to conduct this re-enactment close to the Temple Mount has been regularly rejected by Israeli courts. In April 2017, however, it was approved to hold this event on the square in front of the Hurva Synagogue , in the middle of the Jewish Quarter of the old town . In March 2018, the Jerusalem Administrative Court approved such an event at the Davidson Center, just below the Temple Mount. Sheikh Ekrima Sabri , the imam of the Al-Aqsa Mosque , described the project as a provocation of the Muslim believers.

- Jehuda Etzion and the Chai wekajam movement ("Alive and Existing"). Etzion was part of a terrorist network of Gush Emunim activists. He was sentenced to several years in prison, among other things, for planning to blow up the Dome of the Rock (1984). During his trial in 1985 he wrote “The Temple Mount”, in which he explained his ideology: The construction of the Third Temple was not the first goal, rather the Temple Mount was to be “cleansed” of the Muslim buildings. After his release from prison in 1989, he founded the Chai wekajam movement. Since then, this group has repeatedly drawn attention to itself by attempting to enter the temple area with prayer shawls ( tallitot ) , often accompanied by representatives of the press , which the Israeli police prevent them from doing so in a predictable manner. Arrests and lawsuits are accepted. With their actions, Etzion and his followers try to bring the subject of Jewish prayer on the Temple Mount to the Israeli public. Etzion challenged the Orthodox rabbinical establishment with further provocative actions. For several years in a row, on the day before the Passover festival in Abu Tor, across from the Temple Mount, a billy goat was slaughtered and roasted as a model of the Passover sacrifice.

- Gershon Solomon and the Temple Mount Faithful organization he founded. Solomon, who like many members of the group is personally not a practicing Jew, originally had a Zionist agenda: the Temple Mount was important to him as a symbol of the nation; In the early years, the building of the Third Temple was given less importance than the political control of the place. The Temple Mount Faithful created a high profile through advertising campaigns, demonstrations and trials. Their demonstrations typically ended outside the temple area, where they were stopped by a large police force, with the singing of the HaTikwa . Then Solomon came into contact with Christian fundamentalists, whereby his group took on apocalyptic-messianic traits. Solomon now expected an eschatological battle ( Gog and Magog ), whereupon the God of Israel would be crowned king on the Temple Mount. Because of their secular-nationalist origins and because of the networking in the Christian-fundamentalist milieu, the Temple Mount Faithful have a special position among the activists for a third temple; they are not involved in joint activities. In contrast to Chai wekajam , the Temple Mount Faithful adhere strictly to agreements with government agencies, which have enabled them to achieve some successes, e.g. B. the right to pray at the Mughrabi Gate.

- Jan Willem van der Hoeven and the International Christian Embassy Jerusalem (ICEJ). Van der Hoeven was the official spokesman for the ICEJ until his retirement in 1998. He promoted temple construction in the early 1980s. In 1984 the ICEJ planned a march to the Temple Mount on the occasion of the Sukkot festival , which Mayor Teddy Kollek prevented. After the plans of members of the Lifta Gang and the Jewish Underground to destroy the Dome of the Rock were uncovered in the spring of 1984, Kollek feared that a Temple Mount march by thousands of Evangelicals in the autumn of the same year could have unforeseeable consequences.

- Rabbi Josef Elboim, a Belzer Hasid , and the Temple Building Movement. In 1987 this ultra-Orthodox group split off from the Temple Mount Faithful. Elboim's group avoids any public attention, which is why their activities are little known. Members of the movement visit the Temple Mount as part of the increasingly popular tours and offer prayers - so inconspicuously that, unlike the activists of Chai wekajam, they are seldom stopped by the Israeli police. Because of their non-confrontational nature, Elboim's group succeeded in performing the water ritual (a ritual of the Jewish temple cult) on the haram. Elboim wants to influence the ultra-orthodox community and change the traditionally passive attitude towards the construction of the Third Temple. In doing so, he met resistance from other ultra-orthodox rabbis. Posters were posted in ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods declaring him excluded. On the other hand, Elboim is supported by religious Zionist rabbis.

- Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh and the students of the Od-Yosef-Chai-Yeshiva ("Josef-lives-still-Yeshiva"). Ginzburg is attributed to the Chabad movement, which also means that he is convinced that he is living in the messianic time. Ginzburg's group of students founded a center for temple studies ( El Har Hamor, "Towards the Incense Hill"; Incense Hill is a poetic name for the Temple Mount), whose projects included the revival of the ancient temple guard (Mischmar haMikdasch) . It is a uniformed, paramilitary group that began its activity in 2000 - with no authorization from anyone - to prevent Jews from entering the temple grounds in a state of ritual uncleanliness or with leather shoes.

- Once a month, an umbrella organization of Temple Mount activists organizes a march with thousands of young people along the gates of the Haram ( Sivuv Sheʿarim ), in which the so-called Temple Guard takes part. These parades around the Temple Mount, which have been taking place since 2000, are presented by the organizers as an old Jewish ritual that goes back to the early Middle Ages and is mentioned in texts of the Cairo Geniza . Men are in the front part of the procession, women in the back, and a symbolic mechiza is carried in between to separate them. In other respects the tour is not based on traditional patterns; the liturgy combines Sephardic and Ashkenazi elements. Portable amplifier systems play an important role: at the gates they broadcast the cantillation of psalms, with religious pop music playing in between. Police cordon off the alleys through which the march moves, which is intended to increase the Jewish presence in Palestinian parts of the old town (also acoustically).

- Chozrim laHar , “those who return to the [temple] mountain”, is (2015) the most extreme group of temple activists. Since 2014, members have been trying to bring live goats to the Temple Mount before the festival of Passover, which they want to sacrifice for the festival. The police intervened partly to disrupt public order and partly to violate animal welfare laws. In March 2018, Arab posters were posted asking Muslims to vacate the Temple Mount before the Passover festival. In April 2020, the group called on Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to facilitate Passover offerings on the Temple Mount; then, as in the time of King David, the epidemic (in this case COVID-19 ) will end.

Chronology of the Temple Mount Crises

The most serious attacks on the Temple Mount were the arson attack on the al-Aqsa mosque in 1969 and the shooting on the Dome of the Rock in 1982. The Israeli security authorities and the Waqf staff, however, succeeded in foiling a number of other and potentially devastating attacks.

August 21, 1969

The Australian Denis Michael Rohan carried out an arson attack on the al-Aqsa mosque, which destroyed the wooden pulpit, which dates from the Ayyubid period. Rohan, a member of the Worldwide Church of God , had previously worked as a volunteer in a kibbutz. Sixteen trains of the Jerusalem fire brigade fought the flames for hours, hampered by angry Palestinians, who suspected they were not putting out the fire but adding kerosene. In the afternoon, Prime Minister Golda Meir and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan visited the burnt-out mosque.

At the trial that took place in Jerusalem in the fall of 1969, Rohan made a full confession. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in a mental institution, most of which he spent in Australia. The statements by the Muslim guards that no Israelis were involved in the attack had a de-escalating effect. The horror of the act was great among the Muslim public worldwide; King Faisal had the Saudi Arabian troops prepared for a jihad .

April 11, 1982

Alan Harry Goodman from Baltimore , a mentally unstable Israeli soldier, entered Temple Square in uniform and armed with an assault rifle ( M16 ). He shot and killed one of the Dome of the Rock's guards, gaining entry and shooting a Waqf employee who tried to close the doors. He then holed up in the Dome of the Rock for 45 minutes and shot Muslims out of doors and windows until he ran out of ammunition. In court, Goodman testified that he acted alone and wanted to "redeem" the Temple Mount. Investigators found Kahanist writings in his apartment, and Meir Kahane hired Goodman's attorney. An Israeli court sentenced Goodman to life in prison plus 40 years. His sentences were later reduced several times, eventually he was released and transferred to the United States on October 26, 1997.

Violent Palestinian demonstrations that lasted for weeks resulted from the attack. Yasser Arafat called on the Palestinians to shed their blood in a holy war. Strikes and demonstrations took place in Muslim countries around the world; the UN Security Council condemned the desecration of the Haram and criticized Israel and the Israeli military for the killing and wounding of Muslims on the Temple Mount.

January 26, 1984

Waqf guards prevented an explosives attack on the Temple Mount. The assassins, referred to in the Israeli media as Lifta Gang , were a religious commune led by Shimon Barda, a petty criminal and ex-prisoner who lived in the former Palestinian village of Lifta and who had set up an arms warehouse that included M72 LAW and a crowd of TNT . The ideology of this group was a mix of Hasidism and Christian fundamentalist end-time expectation.

The high potential for destruction that the attack on Barda and his accomplices would have had received relatively little attention in the media, as the Shin Bet uncovered the “Jewish underground” network in the spring of 1984, which included people with military training. This terror group around Michael Livny , Yehoshua Ben-Shoshan and Yehuda Etzion also had avowed intention to destroy the Islamic buildings on the Temple Mount.

October 1990

Temple Mount Faithful's plan to lay the foundation stone of the Third Temple on the Temple Mount on the Jewish high holiday of Sukkot resulted in violent demonstrations by Palestinians. In fact, the group had only received approval from the Supreme Court to perform a water ritual (part of the temple cult) at the Gihon Spring. But rumors spread among the Muslim community that the laying of the foundation stone for the Jewish temple was also planned. Young Muslims were called upon to defend their holy place. Hundreds of Muslims flocked to the Temple Mount while thousands of Jewish worshipers gathered below in front of the Western Wall to receive the priestly blessing ( Birkat kohanim ). When a member of the border police dropped a tear gas canister, the situation got out of hand. From their haram, Muslims pelted the crowded crowd at the Western Wall with stones. The Israeli police stormed the Temple Mount and opened fire on the Muslims; Seventeen people died in an action that severely damaged relations between Palestinians and Israelis.

December 1997

Israeli security forces thwarted a plan by a group around Avigdor Eskin to throw a pig's head with a Koran in its mouth at the haram during Friday prayer in Ramadan. This provocation was intended to lead to violent Palestinian excesses and prevent the Israeli government from implementing the partial withdrawal from the West Bank that it had announced. Eskin was tried and found guilty of placing a pig's head in an old Muslim cemetery and of planning an arson attack on a Dor Shalem Doresh Shalom facility ; the plans regarding the haram could not be proven in court.

July 14, 2014

Two members of the Israeli border police were shot dead with weapons that were brought to the Temple Mount by assassins in front of an entrance to the Temple Mount. The perpetrators and victims were Israeli citizens and belong to the Arab minority.

The three assassins Muhammad Ahmed Muhammad Jabarin, Muhammad Hamad Abdel Latif Jabarin and Muhammad Ahmed Mafdal Jabarin, all from Umm al-Fahm , entered the temple square on July 14th at 3 p.m. with firearms hidden under their clothes (a pistol and two Carlo- Submachine guns ) and a knife. They stayed on the premises for hours and left the haram at 7 p.m. for the Muslim old town . They met the two policemen Kamil Schnaʾan and Haiel Sitawe and shot them down. Other police chased the assassins who fled to the Haram grounds and shot them there. The two dead police officers came from Druze communities in northern Israel; Kamil Shnaan was a son of the former Knesset MP Shachiv Schnaʾan. Government members Naftali Bennett and Moshe Kachlon condoned the families and emphasized the loyalty of the Druze minority to the State of Israel.

Israel then closed the Temple Mount for police investigations for 24 hours, so that the Friday prayer could not take place there for the first time since 1969. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu also ordered metal detectors to be set up in front of the entrances for security reasons. Some Muslims then refused to go through the locks. They saw this as a violation of the status quo and an attempt by Israel to withhold the Temple Mount from the Muslims. As a result, violent clashes with fatalities broke out again.

Eventually the Israeli security cabinet decided to remove the metal detectors. They are to be replaced by “safety inspections based on sophisticated technologies and other means”. Israel thus prevented a diplomatic crisis with Jordan: at the same time there was an incident on the Israeli embassy site in Amman in which two Jordanians died. Jordan then asked to interrogate an Israeli security officer. The agreement found between the two states was that Israel dismantled the metal detectors on the Temple Mount and Jordan allowed the security officer to leave.

A few days after the attack, Amjad Jabarin, also an Arab Israeli from Umm al-Fahm, was arrested for alleging that he had trained the attackers. He was sentenced in October 2019 by a court in Haifa to 16 years in prison for aiding and abetting, as well as a cash payment to the survivors of the victims.

panorama

In the wall, to the right of the Dome of the Rock, the Golden Gate. You can also see the gilded domes of the Maria Magdalena Church on the right and the Dormition Church on the horizon on the left.

In the enlargement you can also see the dome of the Holy Sepulcher immediately to the right of the dome of the rock dome.

literature

- German

- Heribert Busse , Georg Kretschmar : Jerusalem sanctuary traditions. Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1987, ISBN 3-447-02694-4 .

- Werner Caskel : The Dome of the Rock and the pilgrimage to Jerusalem. West German Publishing House, Cologne 1963.

- Meik Gerhards: Again: holy rock and temple. Rostock 2013.

- Max Küchler : Jerusalem. A handbook and study guide to the Holy City . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-50170-2 .

- Benjamin Mazar : Archeology in the footsteps of Christianity. New excavations in Jerusalem. Pawlak, Herrsching 1988, ISBN 3-88199-383-5 .

- English

- Sarina Chen: Visiting the Temple Mount - Taboo or Mitzvah? In: Modern Judaism 34, 1/2014, pp. 27–41.

- Yoel Cohen: The Political Role of the Israeli Chief Rabbinate in the Temple Mount Question . In: Jewish Political Studies Review 11, Spring 1999, pp. 101–126.

- Yaron Z. Eliav: God's Mountain: The Temple Mount in Time, Place, and Memory . Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2005.

- Yaron Z. Eliav: The Temple Mount in Jewish and Early Christian Traditions: A New Look . In: Tamar Mayer, Suleiman Ali Mourad (eds.): Jerusalem: Idea and Reality . Routledge, London / New York 2008. ISBN 978-0-415-42128-7 , pp. 47-66. ( PDF )

- Katharina Galor : Finding Jerusalem: Archeology between Science and Ideology . University of California Press, Oakland 2017. ISBN 9780520295254 . Pp. 146-162.

- Rivka Gonen: Contested Holiness. KTAV Publishing House, Jersey City 2003, ISBN 0-88125-799-0 .

- Oleg Grabar , Benjamin Z. Ḳedar : Where Heaven and Earth Meet: Jerusalem's Sacred Esplanade (= Jamal and Rania Daniel Series in Contemporary History, Politics, Culture, and Religion of the Levant ). University of Texas Press, Austin 2009. ISBN 978-0-292-72272-9 .

- Ron E. Hassner: War on Sacred Grounds. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York 2009, ISBN 978-0-8014-4806-5 .

- Motti Inbari: Jewish Fundamentalism and the Temple Mount: Who Will Build the Third Temple? State University of New York Press, New York 2009. ISBN 978-1-4384-2623-5 .

- Yuval Jobani, Nahshon Perez: Governing the Sacred: Political Toleration in Five Contested Sacred Sites . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2020. ISBN 9780190932381 .

- Nazmi Jubeh: Jerusalem's Haram al-Sharif: Crucible of Conflict and Control . In: Journal of Palestine Studies 45, Winter 2016, pp. 23–37.

- Isaac Kalimi: The Land of Moriah, Mount Moriah, and the Site of Solomon's Temple in Biblical Historiography . In: Harvard Theological Review 83, 4/1990, pp. 345-362.

- John Lundquist: The Temple of Jerusalem. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007, ISBN 0-275-98339-0 .

- Julian Raby, Jeremy Johns (ed.): ʿAbd al-Malik's Jerusalem (= Bayt al-Maqdis . Part 1). Oxford 1992, ISBN 978-0197280171 .

- Julian Raby, Jeremy Johns (ed.): Jerusalem and early Islam (= Bayt al-Maqdis . Part 1). Oxford 1999, ISBN 0-19-728018-8 .

- Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah: Aelia Capitolina - Jerusalem in the Roman Period: In Light of Archaeological Research . Brill, Leiden 2019, ISBN 978-90-04-40733-6 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Yaron Z. Eliav: The Temple Mount in Jewish and Early Christian Traditions: A New Look , London / New York 2008, p. 50.

- ↑ Konrad Rupprecht: The Temple of Jerusalem: Founding of Solomon or Jebusite inheritance? (= Supplements to the journal for Old Testament science . Volume 144) Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1976, p. 15. The discussion of this question is based on the prerequisite that texts of the Samuel Book were written in the Davidic-Solomonic empire and z. B. 2 Sam 12.20 EU contains a reminder of a YHWH temple that already existed at the time of David (apparently the rededicated Jebusite temple, cf. Konrad Rupprecht: The Temple of Jerusalem: Foundation of Solomos or Jebusite Heritage?, Berlin / New York 1976 , P. 102). If, on the other hand, the Book of Samuel was written later, 2 Sam 12:20 does not have such a high source value.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem. A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 603.

- ↑ Wolfgang Kraus , Martin Karrer (Ed.): Septuaginta German. The Greek Old Testament in German translation . German Bible Society, Stuttgart 2009, p. 22.520.

- ↑ Flavius Josephus: Jewish antiquities 1,224.

- ↑ Detlef Jericke: Art. Morija . In: The location information in the book of Genesis: A historical-topographical and literary-topographical commentary . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2013, pp. 153f.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem. A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 126.

- ^ Sarina Chen: Visiting the Temple Mount - Taboo or Mitzvah? , 2014, p. 28.

- ↑ Klaus Bieberstein: The buildings on the Haram - The biblical Temple Mount in its Islamic reception . In: Max Küchler: Jerusalem. A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, pp. 220–277, here pp. 220f.

- ^ Royal Hashemite Court: Jordanian-Palestinian Agreement to Jointly Defend al-Masjid al-Aqsa .

- ↑ UNESDOC Digital Library: Occupied Palestine . Draft decision, submitted by: Algeria, Egypt, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Qatar and Sudan

- ↑ Qantara.de : How political is history? Israel, Unesco and the Temple Mount , October 26, 2016.

- ^ Carlo Strenger: Unesco makes itself impossible. Neue Zürcher Zeitung , October 19, 2016, accessed on June 6, 2019 .

- ^ Yitzhak Reiter: Contested Holy Places in Israel-Palestine: Sharing and Conflict Resolution . Routledge, London / New York 2017, p. Xix. Likewise z. B. Yuval Jobani, Nahshon Perez: Governing the Sacred: Political Toleration in Five Contested Sacred Sites , Oxford 2020.

- ^ Yaron Z. Eliav: The Temple Mount in Jewish and Early Christian Traditions: A New Look , London / New York 2008, p. 49.

- ↑ Thilo Alexander Rudnig: King without a temple. 2 Samuel 7 in tradition and editing . In: Vetus Testamentum 61, 372011, 426-446.

- ^ Sara Japhet : I and II Chronicles: A Commentary . Westminster John Knox press, Louisville / London 1993, p. 551. Nota bene, only the chronicler identifies the Araunas threshing floor with the site of the temple: According to the original story ... the precise location of of Araunah's threshing floor, although certainly in Jerusalem ... is not known, nor is there any indication that this was to be the site of the future temple; correspondingly, I Kings 6.1 does not does not position the Temple on 'the threshing floor of Araunah'. The whole context in fact views the 'threshing floor' as unrelated to other 'holy sites'.

- ^ Yaron Z. Eliav: The Temple Mount in Jewish and Early Christian Traditions: A New Look , London / New York 2008, pp. 54f.

- ^ Yaron Z. Eliav: The Temple Mount in Jewish and Early Christian Traditions: A New Look , London / New York 2008, pp. 55f.

- ^ Yaron Z. Eliav: The Temple Mount in Jewish and Early Christian Traditions: A New Look , London / New York 2008, pp. 59f.

- ↑ Mischna Berakot IX 5 , translation: Dietrich Correns, Marix, Wiesbaden 2005, p. 14.

- ^ Yaron Z. Eliav: The Temple Mount in Jewish and Early Christian Traditions: A New Look , London / New York 2008, p. 62.

- ↑ On 9th Av "it was decided through our fathers that they are not allowed to move into the country ( Num . 14, 28ff. EU ), the temple was destroyed for the first and second time, Better [the last Jewish fortress in Bar-Kochba - Uprising ] was taken and the city [Jerusalem] was plowed up ... "(Mishnah Taanit IV 6, translation by Dietrich Correns, Wiesbaden 2005, p. 269.)

- ↑ Klaus Bieberstein: The buildings on the Haram - The biblical Temple Mount in its Islamic reception . In: Max Küchler: Jerusalem. A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, pp. 220–277, here pp. 244f.

- ^ Mischna Joma V 2 , translation: Dietrich Correns, Marix, Wiesbaden 2005, p. 227.

- ^ Yaron Z. Eliav: The Temple Mount in Jewish and Early Christian Traditions: A New Look , London / New York 2008, p. 63. Contemporary Christians worshiped a corresponding stone in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher; the Muslims adopted the Jewish tradition of the sacred rock.

- ↑ Annette Böckler : Jewish worship, essence and structure . Jewish Publishing House, Berlin 2002, p. 180.

- ^ Eugene B. Borowitz, Naomi Patz: Explaining Reform Judaism . Behrman House 1985, p. 23.

- ↑ Samson Raphael Hirsch: חורב: Attempts on Jissroé̤l's duties in the diversion, first for Jissroé̤l's thinking youths and virgins . Kauffmann, 2nd edition Frankfurt am Main 1889, § 704, p. 550.

- ↑ Motti Inbari: Jewish Fundamentalism and the Temple Mount: Who Will Build the Third Temple? , New York 2009, pp. 4-5.

- ↑ Motti Inbari: Jewish Fundamentalism and the Temple Mount: Who Will Build the Third Temple? , New York 2009, p. 5.

- ↑ Jostein Ådna: Jesus' position on the temple: the temple action and the temple word as an expression of his messianic mission . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2000, p. 434f.

- ↑ Jostein Ådna: Jesus' position on the temple: the temple action and the temple word as an expression of his messianic mission . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2000, p. 128.130.

- ↑ Jostein Ådna: Jesus' position on the temple: the temple action and the temple word as an expression of his messianic mission . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2000, p. 440.

- ↑ Christina Metzdorf: The temple action of Jesus: patristic and historical-critical exegesis in comparison . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2003, p. 2.

- ↑ Martin Vahrenhorst: Cult. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- ↑ Johannes Hahn: Emperor Julian and a third temple? Idea, reality and impact of a failed project . In the S. (Ed.): Destruction of the Jerusalem Temple: Events - Perception - Coping . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2002, pp. 237-262, here pp. 241f.

- ↑ Patrologia Graeca 48, 835, quoted here. after: Johannes Hahn: Emperor Julian and a third temple? Idea, reality and effect of a failed project , Tübingen 2002, p. 242.

- ^ Clemens Thoma : Temple IV. History of Theology . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 9 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2000, Sp. 1327-1329 .

- ^ Yitzhak Reiter: Contested Holy Places in Israel-Palestine: Sharing and Conflict Resolution . Routledge, London / New York 2017, p. 22.

- ^ Corpus Coranicum: Sura 17.1 .

- ^ A b Donald P. Little: Mujīr al-Dīn al-ʿUlaymī's Vision of Jerusalem in the Ninth / Fifteenth Century . In: Journal of the American Oriental Society 115, April-June 1995, pp. 237-247, here p. 240.

- ↑ Donald P. Little: Mujīr al-Dīn al-ʿUlaymī's Vision of Jerusalem in the Ninth / Fifteenth Century . In: Journal of the American Oriental Society 115, April-June 1995, pp. 237-247, here pp. 241f.

- ↑ Ilan Ben Zion: Jerusalem mufti: Temple Mount never housed Jewish Temple . In: The Times of Israel, October 25, 2015.

- ↑ Israel Finkelstein , Neil Asher Silberman : David and Solomon. Archaeologists decipher a myth . (Original: David and Solomon, In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition .) CH Beck, Munich 2006, pp. 154f.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem. A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 127.

- ^ Ehud Netzer : The Architecture of Herod, the Great Builder . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2006, pp. 143-150.

- ^ Ehud Netzer: The Architecture of Herod, the Great Builder . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2006, pp. 160f.

- ^ Ehud Netzer: The Architecture of Herod, the Great Builder . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2006, p. 161, cf. Middot II, 3rd

- ^ Yaron Z. Eliav: The Temple Mount in Jewish and Early Christian Traditions: A New Look , London / New York 2008, pp. 57f.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina. The Roman policy towards the Jews from Vespasian to Hadrian (= Hypomnemata . Volume 200). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2016, pp. 83–85.

- ↑ Münzkabinett Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, interactive catalog: Aelia Capitolina 130-138 AD.

- ↑ Andrew Burnett, Michel Amandry, Jerome Mairat: Roman Provincial Coinage . Volume III: Nerva, Trajan and Hadrian (AD 96-138) , 2015, No. 3963 .

- Jump up ↑ Leo Kadman: The Coins of Aelia Capitolina (= Corpus Nummorum Palaestinensium , Volume 1), Israel Numismatic Society , Jerusalem 1956, No. 3, Plate 1.

- ↑ a b c d Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah: Aelia Capitolina - Jerusalem in the Roman Period: In Light of Archaeological Research , Leiden 2019, pp. 117–119.

- ^ Cassius Dio: Roman History , 69.12.1.

- ↑ a b Yoram Tsafrir: The Temple-less Mountain. In: Oleg Grabar, Benjamin Z. Kedar: Where Heaven and Earth Meet: Jerusalem's Sacred Esplanade , Austin 2009, pp. 72–99.

- ^ Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt. The Bar Kokhba War , 132-136 CE. Brill, Leiden 2016, pp. 125f.

- ↑ Hieronymus: Commentarius in Isa. 9.2 .; only equestrian statue: Commentarius in Matthew 24.15.

- ↑ a b Max Küchler: Jerusalem. A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 144.

- ↑ Bernard Flusin: L'Esplanade du Temple à l'arrivée of Arabes d'après deux récits Byzantins . In: Julian Raby, Jeremy Johns (eds.): `Abd al-Malik's Jerusalem , Oxford 1992, pp. 17-31.

- ↑ Klaus Bieberstein: The buildings on the Haram - The biblical Temple Mount in its Islamic reception . In: Max Küchler: Jerusalem. A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, pp. 220–277, here p. 236.241.

- ↑ Klaus Bieberstein: The buildings on the Haram - The biblical Temple Mount in its Islamic reception . In: Max Küchler: Jerusalem. A handbook and study guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, pp. 220–277, here pp. 246–248.

- ↑ Klaus Bieberstein: The buildings on the Haram - The biblical Temple Mount in its Islamic reception . In: Max Küchler: Jerusalem. A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, pp. 220–277, here pp. 238f.

- ↑ Yuval Jobani, Nahshon Perez: Governing the Sacred: Political Toleration in Five Contested Sacred Sites , Oxford 2020, pp. 141f.

- ↑ Klaus Bieberstein: The buildings on the Haram - The biblical Temple Mount in its Islamic reception . In: Max Küchler: Jerusalem. A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, pp. 220–277, here p. 234.

- ↑ a b c d Yuval Jobani, Nahshon Perez: Governing the Sacred: Political Toleration in Five Contested Sacred Sites , Oxford 2020, p. 142.

- ↑ See Sylvia Schein: Between Mount Moriah and the Holy Sepulcher: The Changing Traditions of the Temple Mount in the Central Middle Ages . In: Traditio 40 (1985), pp. 82-92; Heribert Busse: From the Dome of the Rock to the Templum Domini . In: Wolfdietrich Fischer , Jürgen Schneider (Hrsg.): The Holy Land in the Middle Ages: Meeting place between Orient and Occident . Degener, Neustadt / Aisch 1982, pp. 19–31.

- ↑ Michelina Di Cesare: The “Qubbat al-Ṣaḫrah” in the 12th Century . In: Oriente Moderno , Neue Serie, vol. 95, 1/2 (2015), pp. 233-254, here pp. 240–242.