Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem

The Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem ( Hebrew הַרֹבַע הַיְהוּדִי haRovaʿ haJehudi , Arabic حارة اليهود, DMG Ḥārat al-Yahūd ) is one of the four traditional neighborhoods in the southeast of Jerusalem's old town . It is located in East Jerusalem and comprises 133 dunams (= 133,000 m²). The present area was created by the Israeli government after the capture of the old town in the Six Day War ; she was referring to the (smaller) Jewish quarter as it had existed before the Palestine War in 1948. This war and the subsequent Jordanian administration had caused severe damage to the structure of the district, so that a comprehensive reconstruction of the district was necessary, which took more than 15 years. On this occasion, extensive archaeological excavations took place, the results of which are partly visible as archaeological zones in the cityscape, partly in museums under the new buildings. The new construction of the quarter was carried out with the integration of older buildings uniformly in a neo-oriental style. Since the 1990s, the Jewish Quarter has been one of the Jerusalem districts with a predominantly ultra-Orthodox population. Numerous Talmud universities have settled near the Western Wall, and their students live in the district.

geography

Since the Jewish Quarter is located within the historic old town wall, access is through the gates of this wall ring. Two gates in the south wall are the direct route into the quarter:

- Dung Gate : Access to the Western Wall Plaza in front of the Western Wall , expanded in 1985 for the passage of buses.

- Zion Gate : The two parking lots of the Jewish Quarter are accessible via the street of the Armenian Patriarchate; It is also of great importance for emergency vehicles and deliveries of goods.

In addition, the Jaffator in the west and the Damascus Gate in the north are important for the residents of Jerusalem's New City, because from there you can walk to the Jewish Quarter on the main axes of the old town. This is especially true for the valley road ( Tariq Al Wad / Rechov haGai), the shortest route from the districts of the Charedim in the north-west (e.g. Meʾa Sheʿarim ) to the Western Wall.

History until 1967

Ancient Jewish metropolis

On the area of the Jewish Quarter was the new town ( haMischne ) of the Iron Age Jerusalem, which was developed as a living area at the time of King Hezekiah and secured with a city wall (floor monument "Wide Wall"). This city expansion is considered to be a consequence of the fall of the northern Reich of Israel (722/720 BC), because refugees from the north streamed into the southern Reich of Judah, so that the population of Jerusalem increased.

In the Hellenistic period and until the Jewish War , the area of today's Jewish Quarter with the upper town and the lower town of ancient Jerusalem was built on. Numerous public buildings are known from literature: a gymnasium with ephebie and ring school , the palace of the Hasmonean kings , a town hall, a theater and a hippodrome . Under Herod the “transformation to Jewish. Metropolis and at the same time a bright Roman. Royal city "; the temple platform was enlarged to today's dimensions and the temple with its courtyards and portico was built on it. Large staircases and bridges brought the pilgrims from street level to the height of the temple grounds. To the west and south of the temple, according to archaeological findings, were the villas of the priestly aristocracy, while industrial zones shaped the lower part of the ancient city.

Late antique and Byzantine city

With the Roman occupation in AD 70 , Jerusalem was completely destroyed, and the re-establishment of Aelia Capitolina in the reign of Emperor Hadrian was a pagan city that Jews were forbidden to enter. This ban also applied to Byzantine Jerusalem, which has been upgraded to a Christian pilgrimage destination since Emperor Constantine .

The center of the unfortified civil city of late antiquity was on the area that is now part of the Christian and Muslim quarter of the old town. The Cardo secundus crossed the area of today's Jewish Quarter in a north-south direction; to the west of this road was the legionary camp. During the Byzantine period, the Tenth Legion was relocated, allowing the civil city to expand south. This new town now also comprised the area of today's Jewish Quarter. On the extended Cardo Maximus, the Nea Maria Church with outbuildings (hospice, hospital, library; floor monument) was built, which was larger than the Constantinian Church of the Holy Sepulcher .

Early Islamic, Crusader and Mameluke city

History of the Jewish Community of Jerusalem

Only in early Islamic times was a Jewish community able to re-establish itself in Jerusalem; From now on one can speak of a "Jewish quarter" in the city, although its location has changed over the centuries:

- In the 11th century, the district was southwest of the Haram with a "cave synagogue" in the wailing wall, which is documented several times in the texts from the Cairo Geniza . This “cave” suffered severe damage in an earthquake in 1033 and was repaired by the Jewish community. It is tentatively identified (e.g. by Dan Barag) with the Warren Gate and its entrance hall.

- The Zion Gate was described by the chronicler Mujir ad-Din (1496) as the “Gate of the Jewish Quarter”, which apparently alludes to the location of this oldest Jewish quarter. When the Crusaders captured Jerusalem in 1099, they murdered Muslim and Jewish residents; for the following period, the sources only report on individual Jewish families.

- Since the north-eastern part of Jerusalem is sometimes referred to as Judaria or Juvrie in sources from the time of the Crusaders , it seems that around 1050 to 1099 there was also a Jewish population in this area who was murdered when the city was conquered.

- When Nachmanides visited Jerusalem in 1267, he found only two Jewish families. He converted a ruin into a house synagogue and founded a small community on today's Zionsberg . After the Franciscans obtained the right to settle here from the Mameluk rulers in 1333 , the Jewish community had to give way.

- As a result, the Jewish Jerusalemites moved within the city and settled near the Western Wall. This is where the Mameluk Jewish Quarter was built - i.e. in the area of today's Jewish Old Town. Ruth Kark and Michal Oren-Nordheim believe that the location of this quarter reflects the subordinate social position of the residents. Because the socially dominant groups of Muslims and Christians were able to secure the more attractive areas of the old town as living space, and the Jewish residents settled in the part of the city that was topographically lowest. The municipal sewer that left the old town at the Dung Gate ran here .

- The community grew through Sephardic Jews who came here after the expulsion from Spain (1492). Its center was the Ramban Synagogue until 1586 . This oldest synagogue in Jerusalem, which has been attested since around 1400, was created by converting a basilical room (perhaps the abandoned Crusader Church of St. Martin). In 1586, the governor of Jerusalem, Abu Seifin, forced its closure and profanation.

- In addition, there was a Karaite congregation in Jerusalem with the center of the Anan ben David synagogue since the 15th century .

Other buildings in the (today's) Jewish Quarter

In early Islamic times, not only the ruins of the Jewish temple, which was destroyed in 70 AD, were reinterpreted with Islamic buildings. The southern wall of the city was given its current course, and four large caliph's palaces were built in the area between the southern wall and Cardo secundus, as Jerusalem was temporarily the residential city in this phase.

The building complex St. Maria Alemannorum (church, hospice and hospital; ground monument) and the market hall at Cardo maximus offer Christian traces of the crusader era. Smaller churches in this part of town were St. Martin and St. Peter ad Vincula.

The minaret of the Sidna Umar Mosque dates from the Mamluk period and was built in 1473.

The Maghrebian Quarter ( Harat al-Maghariba ), which was on the site of the Western Wall Plaza until 1967 , was a religious foundation (Waqf) established by al-Malik al-Afdal in 1193 for the benefit of Muslim pilgrims and scholars from North Africa. After the certificate issued about it was lost, the foundation text was written down again in 1595. The Maghreb district was defined as the area that was in the south of the city wall, in the east of the wall of the Haram (= Western Wall), in the north of the so-called arcades of the Umm al-Banat and in the west of the official seat of the Qadi of Jerusalem and two residential buildings was delimited. The administration of this entire area was the responsibility of the respective sheik of the Magrebiner district.

Ottoman city

In the 16th century, the Ottoman authorities followed the principle that Jewish and Christian places of worship should be preserved if they had existed before the Muslim conquest, but not if they were built afterwards. This put the synagogues in constant danger of closure if they turned out to be less old than the Jewish community claimed. For this reason, a synagogue in Jerusalem was closed in 1588. In response, Jewish communities set up rooms in private homes; an example from Jerusalem is known in which Sultan Murad III. In 1581 ordered the Qadi of Jerusalem to punish Muslims who threatened and molested those who worshiped in such a private synagogue.

In Mameluke Jerusalem the street level was on a level with the Herodian temple platform or the Islamic haram. Only at the beginning of the Ottoman period, legendarily associated with Sultan Suleyman I , was a piece of the ancient western wall exposed and made available to the Jewish community as a wailing wall for their rituals. The first description was given by an anonymous Jewish author in 1522: “The western wall that survives is not the entire west side, but only part of it, between 40 and 50 cubits long. Half of its height is from Solomon's time, as the big old stones show. ”In the 16th century, the 22 m long, 3 m wide corridor was laid in front of the wall, which was used for Jewish worship until the Western Wall Plaza was exposed in 1967 Was available.

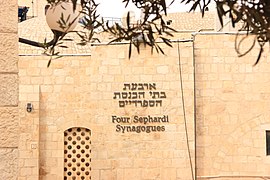

At the end of the 17th century, an epidemic raged in Jerusalem that claimed many lives among the Jewish population. The settlement attempt of an Ashkenazi community in 1699 was canceled after twenty years. Since the 1740s, wealthy Sephardic families have settled in Jerusalem, whose parish life developed around the four Sephardic synagogues . This small eighteenth-century community was a kind of daughter community of the Constantinople Jewish community and was administered by them.

The severe earthquake of 1837 destroyed Jewish settlements in Safed and the surrounding area. Many of the survivors moved to Jerusalem, increasing the city's Jewish population to 3,000–3200. Ira Sharkansky gives the number of Jewish Jerusalemites at the end of the 1860s as 11,000, for 1910 as 45,000.

The population of the individual quarters was not religiously homogeneous in Ottoman times; rather, Muslim families lived in the Jewish quarter, and Jewish families lived in the Muslim quarter adjacent to the north. Muslim foundations ( Auqaf ) owned numerous houses in the Jewish Quarter. Jews seldom acquired real estate in Jerusalem until the late 19th century, with the exception of the Jewish exclaves in the Muslim Quarter. As foreign nationals, it was hardly possible for the Perushim, who came from Eastern Europe, to purchase land , and the few private Jewish homeowners in the Jewish Quarter were long-established Sephardic families. A common arrangement was that the development around an inner courtyard belonged to a Muslim family. Members of this family lived in a caretaker's apartment on the ground floor. The rented apartments were given to Jewish households with whom there was close social contact, as the caretaker did their work on the Sabbath and public holidays.

A new Ottoman law in 1909 allowed communities to be registered as owners of public buildings (such as synagogues). Previously, there was only a customary law for the numerous buildings used for religious purposes in Jerusalem, or a fictitious private person officially acted as the owner.

The individual goods were assigned to certain religious communities in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Sephardic Jews were mainly active in the textile business. Ashkenazi Jews traded in wine and had their center in the Suq Chan ez period . A peculiarity of Jerusalem was that markets were hardly located within the neighborhoods, but on the streets that delimited the neighborhoods and therefore formed a contact zone between the respective residents and the numerous pilgrims and travelers. For the Jewish Quarter these were:

- al-Maidan Street as the border with the Christian quarter;

- Tariq Bab as-Silsila as the border to the Muslim quarter.

A striking difference between the various quarters was that there were many gable roofs in the Christian and Armenian quarters , while the houses in the Muslim and Jewish quarters had domed roofs , some also had flat roofs. The building fabric of the old city of Jerusalem is generally described as poor for the middle of the 19th century. The buildings were mostly made of stone (including spolia ), but occasionally also made of adobe. Since it was mostly not residential property, the residents invested little in the renovation and simply gave up a collapsed room or converted it into a garbage dump. In the Jewish Quarter in particular, with its mostly poor population, the sanitary conditions were difficult, which led to epidemics several times in the middle of the 19th century.

In the second half of the century, these problems were addressed and south of the traditional Jewish quarter, the Batei Machse housing complex (בתי מחסה “Houses of Refuge”) was built, which improved the housing situation of the Jewish population of Jerusalem. The initiative came from the Anschei Hod, a subgroup of the Peruschim from Holland and Germany; the project was supported by the Austrian consulate and realized with donations from Europe. Around 190 apartments and two synagogues were built between 1861 and 1890. The apartments (two rooms and a kitchen each, shared courtyard with cistern) were raffled among the needy families in a lottery.

Most of the public buildings in the Jewish Old Town were built at the same time: the Misgav laDach Hospital (משׂגב לדך “Protection of the Oppressed”), schools and two representative synagogues (Churva Synagogue and Tifferet Jisraʾel Synagogue), whose domes show the image of the area shaped. The construction of the Churva Synagogue was preceded by lengthy negotiations with the Ottoman authorities in order to obtain a building permit at all and to be able to erect a representative building. The Turkish architect Asad Effendi had also made plans for several large mosques in Istanbul. The Churva Synagogue therefore resembled Ottoman mosques from the 16th to 19th centuries: a building on a square base, vaulted by a large dome, including a series of surrounding windows, and large arched windows on the outer walls that give light to the central prayer room . It had been Jerusalem's main synagogue since 1864 and also the central assembly room for Jewish Jerusalemites until the 1930s. Theodor Herzl visited it in 1898. Zeʾev Jabotinsky recruited volunteers for the Jewish Legion here, and it was here that the Jewish Legion's flag was handed over in 1917 after the British capture of Jerusalem.

20th century

The Ottoman census of 1905 gives the number of families by neighborhood and religious affiliation for the (approximate) area of today's Jewish Quarter as follows:

| neighborhood | location | Jews | Muslims | Christians |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ḥārat aš-Šāraf | To the west of today's Rechov Bet ChaBaD street (the entire current Armenian Quarter belonged to this neighborhood) | 127 | 40 | 215 |

| Ḥārat Bāb as-Silsila | East of the street Rechov Bet ChaBaD | 711 | 548 | - |

| Ḥārat Nabī Dāwūd | Northeast of the Zion Gate | - | 85 | - |

Foreign nationals are not included in this census.

Since 1870, many residents of the densely populated Jewish Quarter moved to the newly emerging districts of the Neustadt, which offered a higher quality of living. What remained was a very poor and particularly religious section of the population. This trend continued during the British mandate: Modern infrastructure developed in the New Town, the population increased there, and in 1946 only about 2% of Jewish Jerusalemites lived in the Old City. During the mandate there was increased tension between Jewish and Arab Jerusalemites, and this prompted Jewish families to move from other old town quarters to the Jewish quarter, where living space was available as a result of the migration to the new town. In the run-up to the Palestine War, ethnic segregation according to neighborhoods took place.

Wailing Wall at Yom Kippur (1920)

Jordanian troops besieged the Jewish quarter during the Palestine War . The ideological contradictions between the Zionist defenders and the strictly religious and therefore anti-Zionist-oriented resident population became clear. For many fighters, the uncooperative behavior of the people they wanted to protect was incomprehensible. Zionist historians rather emphasized the solidarity of fighters and residents and their creativity (supply by an improvised cable car): "This made the Jewish quarter, which for a long time only stood for religiosity and poor living conditions and was discursively devalued, part of Zionist historiography," said Johannes Becker.

After the Jordanian conquest of the old town , all Jewish residents, around 1500 people, were expelled. Here cared Paul Ruegger from the International Committee of the Red Cross personally for safe passage into Israeli-held western Jerusalem. The new Jordanian state concentrated on expanding its capital, Amman, and the surrounding area; the West Bank and the Old City of Jerusalem were neglected under the Jordanian government. To make matters worse, the old town was cut off from the infrastructure that was in the new town, now Israeli territory. Jordan invested in Christian and Muslim pilgrimage tourism to Jerusalem in the 1960s. The decaying Jewish Quarter was excluded, and Jewish religious sites were deliberately profaned. The Jordanian administration blew up the two great Ashkenazi synagogues because of their military importance. It redefined the Western Wall as a purely Islamic holy place dedicated to Muhammad's magical mare al-Buraq . According to Israeli sources, shortly before the Six Day War, an American construction company was commissioned to completely demolish the Jewish quarter and create a public park on the site. Some Palestinian refugees who had moved into the vacant houses in the interwar period were evacuated and settled in a camp near Shu'afat.

The quarter since the reconstruction in 1967

Shortly after Jordan's entry into the Six Day War on June 5, 1967, Israeli troops captured the poorly defended Old City of Jerusalem on June 7. The Israeli government then evacuated the Arab residents of the Jewish Quarter. She set a one-year deadline for an inventory of the district and development of an urban planning concept. 29 acres, mostly Jewish real estate prior to 1948, were expropriated by the government, including the area in front of the Western Wall (not the wall itself). But the building ensembles Ja'ouni, Bashiti and Anabousi in the Armenian Quarter were also assigned to the Jewish Quarter in 1967. The expansion to the west can be seen on the adjacent map. The Old Yishuv Court Museum , which opened in 1976, is located in this area traditionally assigned to Armenian, today the Jewish Quarter . It deals with the everyday life of the Jewish inhabitants of Jerusalem before 1948 and thus has a significantly different emphasis than the archaeological museums shown as sights in the adjacent map.

A committee led by Prime Minister Levi Eschkol was tasked with planning the reconstruction. The chief architect was Shalom Gardi. A state housing association was founded in 1969 ( Company for the Reconstruction and Development of the Jewish Quarter , CRDJQ). The Israel Land Authority transferred the area of the Jewish Quarter to the CRDCJ in a long-term lease. The housing association built around 500 residential units and 100 commercial premises, which they sublet to the residents of the district, as well as public buildings. It does not report to the mayor of Jerusalem, but to the Israeli Ministry of Housing.

In 1978 the East Jerusalem resident Muhammad Said Burqan, whose family had owned residential property in the Jewish Quarter since the 1930s, sued the Supreme Court because he was not allowed to buy an apartment in the renovated old town. The court dismissed Burqan's complaint. The judge Meʾir Shamgar justified the decision by stating that there were four ethnically and religiously homogeneous old town quarters, and that this had been the developed infrastructure of Jerusalem since the 11th century at the latest. In this view, the Israeli government continued a centuries-old tradition by making the new apartments exclusively available to Jews, so this was not an act of discrimination. Citing this ruling, the state housing association attempted to remove a tenant from the Jewish Quarter in 2011 because he was an Evangelical Christian (he was involved in promoting cooperation between Evangelical and Israeli right-wing organizations).

Urban planning concept

The development concept designed by Ehud Netzer , Joe Savitzky and Arie Sonino envisaged a residential area, an area for Jewish religious and public buildings and a central, touristic area. The team of architects was disbanded after the work was completed in 1980, but there were also construction projects in the district afterwards.

The aim was to create an old town quarter that was attractive as a place to live for Jewish Israelis of various religious and cultural backgrounds. The pedestrian-only road network was given new, Hebrew names. The renaming was not here, as elsewhere, at the expense of old Arabic names, but rather old Jewish names; it followed a twofold logic: to reduce the religious component and to give the entire area of the district a uniform appearance, enlarged by additional living areas. The architects decided to keep the historic road network with minor modifications. The resulting, angled development creates changing light-shadow contrasts on the facades and thus contributes to the tourist attraction. Three parallel streets open up the quarter in a north-south direction: Rechov Bet ChaBa "D , Rechov haJehudim and Rechov Misgav Ladach. The residential units are accessed via small access roads, which wanted to protect the privacy of the residents away from the tourist and business traffic Today there are many ultra-Orthodox families living in the Jewish Quarter, this separation has a positive effect and prevents tension between the religious lifestyle of the residents and the mostly secular tourists. In order to create public spaces for visitors to the city, the city planners saved areas for The central market square was planned to the east of the ruins of the Churva Synagogue. The concept was in many ways linked to the historical development, for example through the clusters of residential units, the numerous access roads and the limitation of the building height.

Simone Ricca advocates the thesis that no reconstruction of the district in the state before 1948 was planned, but a selective reconstruction that was supposed to recreate a “mythical”, ancient Jewish Jerusalem. There were e.g. For example, there was no static analysis of the existing structure, but the buildings, which were generally referred to as “ruins”, were cleared with heavy equipment in order to build something new in their place. Shalom Gardi described the task as follows: “The entire Jewish Quarter was a poor residential area that had been built with poor materials and techniques. There were no monuments in this area that made a complete reconstruction necessary. ”He compared it with the old town of Acre , which requires a more complex restoration due to its more valuable building structure. Meʾir Ben-Dov, who was involved as an archaeologist in the investigation of the quarter before the reconstruction, estimated that around 20% of the historical building fabric was preserved and around a third was completely rebuilt. According to Matti Friedman, the planning of the reconstruction had a twofold objective: on the one hand, an old town quarter inhabited by Jewish Israelis was to be created here, on the other hand, "a symbolic landscape and an ideological Mecca" that supported the historical claim of Judaism to the city of Jerusalem.

After the Maghreb district was torn down, the city planners created a spacious plaza in front of the Western Wall, which visibly expressed the symbolic significance of the Western Wall for the State of Israel and the Jewish diaspora . This square is divided into two parts: the religious area in front of the wall, designed according to rabbinical guidelines, and the area that is used for military parades, swearing-in ceremonies, commemorations for fallen soldiers, events for Jerusalem Day , etc. (Israel's civil religion ).

Residential development

In the architectural history of Israel, the reconstruction or new construction of the Jewish Quarter was a turning point. On Bauhaus architecture followed after the founding of standardized mass housing to supply the many immigrants quickly with living room. In the late 1960s the trend was towards regionalism and postmodernism . The Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem conceived in this phase, built in a kind of neo-orientalism, was later considered a model of traditional Jewish architecture by Israeli architects. David Kroyanker writes: “What emerged here was a new architectural vocabulary based on old tradition.” Specifically: Oriental arches, vaults, domes, protruding consoles and arcades were combined with “Mediterranean” -type houses in a seemingly random arrangement. The buildings are clad with Meleke and thus have a uniform appearance, but they were built in the manner customary in Israeli housing construction at the time and not with traditional construction techniques. According to Rehav Rubin and Doron Bar, the result of the rebuilding is a new landscape whose connection to the pre-1948 neighborhood is extremely vague. In order to meet the requirements with regard to the number of residential units, the houses were given more floors than in the previous development before 1948.

The layout of the residential units was based (still in the spirit of the Zionist pioneering days) from an “egalitarian” population and roughly followed the official requirements for the French Hill residential area . According to Uri Ponger, the expectation was that wealthy residents would move in and upgrade the houses on their own. The kitchens and sanitary facilities in the residential units met the needs of strictly religious households. In the first few years, the Jewish Quarter was dominated by upper-middle-class Israelis, who accepted restrictions in order to live in a particularly historic location. These residents were integrated into a dense social network and were also in close contact with the architects, which led to some technical improvements. In this socially homogeneous quarter there were two private apartments that had a special position: the house of the state auditor Jitzchak Nebenzahl (Ahrens, Burton & Koralek, 1971–1973), which is considered the most architecturally interesting residential building in the quarter, and the house of the Deputy Prime Minister Jigal Allon (Elieser Frenkel, 1968).

The historical Batei Machse building complex, an ensemble of apartments and religious institutions built around 1860 to 1890, was still preserved to the extent that it could be renovated. Three architects who had experience in the renovation of the old town of Jaffa were commissioned to do this: Elieser Frenkel, Jaʿakov Jaʿar and Saʾadja Mendel. Here too, however, a profound change took place. Frenkel's “arcade house” placed modern residential units on the restored old building fabric. The representative Rothschild house in the Batei Machse building complex suffered comparatively little war damage. After the reconstruction of the housing association, it served as a quarter and is one of the most striking buildings in the quarter.

Public buildings

The Jewish Quarter community center is located at 20. Misgav-Ladach-Strasse. It offers events and courses for all generations, as well as information events on community issues. In the immediate vicinity there are two libraries for the residents of the neighborhood: the municipal district library and the Torani library with a range of books selected by the Torah culture department of the Jerusalem city administration (Torani libraries are also available in other religiously influenced libraries Jerusalem neighborhoods).

Educational institutions

There are several schools and kindergartens under state supervision in the Jewish Quarter, but no secular schools. The only co-educational national religious elementary school is located at 16 Batei-Machse-Strasse; it has 226 students who come not only from the neighborhood but also from other parts of Jerusalem. The school is attractive to families who have immigrated to Israel from English-speaking countries. There are also the national religious Moria schools for boys (179 pupils) and for girls (200 pupils). The other five state schools, including two junior high schools, are ultra-Orthodox. In addition, there are several private ultra-Orthodox schools in the neighborhood, where the state does not oversee the curriculum ( exempte schools ). In the 1990s, a local rabbi ruled that a 19th-century ban on teaching English after 4th grade continued in the neighborhood's schools. This was interpreted as a shift in emphasis from the modern-Orthodox to the ultra-Orthodox orientation in the education system.

The Jewish Quarter is known for its numerous yeshivot, most of which are located near the Temple Mount or the Western Wall Plaza. Large institutions in this area are:

| image | Surname | Number of students | founding year | description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Porat Josef ( Hebrew פורת יוסף) | 250 | 1923, new building after being destroyed in 1948 | Modernist building (architect Mosche Safdie), an exception to the uniform neo-orientalist style of the district. Leading Sephardic ultra-orthodox yeshiva. The majority of the faculty and students come from communities in the Judaism tradition of Baghdad and Aleppo. |

|

Yeshivat haKotel ( Hebrew ישיבת הכותל) | 340 | after 1967 | Leading Hesder Yeshiva founded by Rabbi ʾArje Bina. The building (Wohl Torah Center) was built over the archaeological site of the Herodian Quarter according to plans by Eliezer Franco. The building complex includes a Bet Midrash for up to 500 people, a cafeteria, an event hall, a lecture hall, classrooms, a synagogue and offices; In addition to the dormitory for up to 350 people, this yeshiva has 14 apartments for married students and their families. The yeshiva uses an area of 10,000 square meters within the quarter for boarding school and student apartments. |

|

ʾEsch haTora ( Hebrew אש התורה) | 215 | 1974 | Headquarters of a worldwide organization founded by Rabbi Noach Weinberg |

|

Netiv ʾArje ( Hebrew נתיב אריה) | about 170 | 2003 | Main building (since 2003) particularly close to Tempelplatz, student apartments on the neighboring Misgav Ladach street. Netiv Arje is a foundation of the Jeschiva haKotel. |

|

Chaje ʿOlam ( Hebrew חיי עולם) | Founded in 1886 as Hasidic Jeshiva, the second largest Ashkenazi Jeshiva in Jerusalem, 1933 relocation of the facility to Meʾa Sheʿarim. Today the complex in the Jewish Quarter is used by Hasidim in Brazław and by Jews who have newly found a religious way of life ( Baʿal Teschuva movement ). | ||

| Midreschet haRova ( Hebrew מדרשת הרובע) | 1990 | Offers one-year, nationally religious-oriented study programs for Jewish women of the diaspora. The complex includes a dormitory, a cafeteria and several apartments in the old town. |

Bet haSofer , the "writer's house", was founded by the Hebrew Writers' Association in 1970 in the Jewish Quarter with the aim of making Hebrew literature known to the population. The purely secular program included workshops, lectures and educational offers. Bet haSofer was not financed by donations, but by funds from the Jerusalem city administration. The facility soon ran into financial difficulties and moved from the three-story building in the Jewish Quarter to West Jerusalem.

The Sapir Jewish Heritage Center was an educational and cultural institution in the neighborhood of the Churva Synagogue. Founded in 1974, the Heritage Center has a basic Zionist orientation and advocates tolerance, pluralism and the dismantling of prejudices. In 2014 the educational offers were restricted for financial reasons, in 2016 the property was sold to the Ministry of Defense ; After renovation, the center has been used as a seminar for commanders of the Israel Defense Forces since 2018 .

Population development

The population in the rebuilt neighborhood initially had a larger secular segment. It was a clear announcement that Jigal Allon, a prominent former Palmach commander and secular Israeli, was moving to the Jewish Quarter.

From the beginning, the quarter lacked a secular infrastructure (kindergartens, schools, social facilities), a disadvantage in the eyes of intellectuals and artists, who were originally planned as residents of the quarter alongside public figures. National religious Israelis increasingly settled in the neighborhood, and the growing presence of yeshivot in the neighborhood further contributed to secular Israelis moving away. The Jewish Quarter of the Old City developed into an ultra-Orthodox residential area, a trend that can also be seen in other historic Jerusalem districts. In 1983 40% of the population were secular and 60% religious, in 2006 5% were secular, 25% national-religious and 70% ultra-Orthodox.

| year | population |

|---|---|

| 1977 | 720 |

| 1981 | 1600 |

| 1988 | 2200 |

| 2011 | 3329 |

| 2012 | 3350 |

| 2013 | 2820 |

| 2014 | 2900 |

| 2015 | 2960 |

| 2016 | 3020 |

| 2017 | 3130 |

elections

In the parliamentary elections in Israel in 2013 , 1,347 people were eligible to vote in the Jewish Quarter, 66.6% voted. The distribution of votes was as follows (only parties over 2%):

| Political party | Share of votes (in%) | Comparison of share of votes nationwide (in%) |

|---|---|---|

| United Torah Judaism | 31.8 | 5.16 |

| HaBajit haJehudi | 30.3 | 9.12 |

| Schas | 11.4 | 8.75 |

| Likud - Israel Beitenu | 9.3 | 23.34 |

| Otzma leJisraʾel | 9.2 | 1.76 |

In the 2015 parliamentary elections in Israel, 1,255 people were eligible to vote in the Jewish Quarter, 67.8% voted. The distribution of votes was as follows (only parties over 2%):

| Political party | Share of votes (in%) | Comparison of share of votes nationwide (in%) |

|---|---|---|

| United Torah Judaism | 31.1 | 4.99 |

| HaBajit haJehudi | 19.8 | 9.12 |

| Likud - Israel Beitenu | 17.6 | 23.40 |

| Jachad - Otzma Jehudit | 17.3 | 2.97 |

| Schas | 8.0 | 5.74 |

| Avoda | 2.1 | 11.39 |

tourism

The Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem's Old City is one of Israel's main tourist attractions. The Israeli Ministry of Tourism gave the following figures for 2014: Israel was the destination of 3.3 million tourists, of whom 82% visited Jerusalem. Here the Western Wall was the main tourist destination (74% of all Israel tourists), followed by the Jewish Quarter (68%). In 2014 it attracted more tourists than Christian pilgrimage sites such as the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (59%), the Via Dolorosa (53%) and the Mount of Olives (52%).

Attractions

Historical synagogues

The four Sephardic synagogues suffered relatively little damage to the structure under Jordanian administration, but all of their interior furnishings were destroyed. After the restoration by Dan Tanai, the rededication of the churches took place in 1973, an event that was honored with special postage stamps. The Karaean Anan ben David Synagogue , a building from the Mameluke period, was also restored after being severely damaged in the Palestine War.

The Ramban Synagogue , profaned as early as 1587 , was virtually rediscovered by Israeli archaeologists in a building with a medieval structure that had been a small dairy under Jordanian administration . According to plans by Dan Tanai, the building was restored after 1967 and in the following years developed into the central synagogue of the district, which is used for worship by believers of various liturgical traditions. Right next to it is a former mosque, built in 1397 ( Jami al-Kabir / Sidna Omar ).

The two Ashkenazi synagogues of the 19th century with their domed roofs that characterize the cityscape were badly damaged in the Palestine War and were blown up under the subsequent Jordanian administration. They were left as ruins and memorials when the district was rebuilt. In particular, the ruins of the Churva Synagogue with their striking arch, restored in 1977, shaped the image of the district. The Churva Synagogue was rebuilt in historical form following a Knesset resolution in 2002 and inaugurated in 2010. In 2014, the Knesset also decided to rebuild the Tifferet Jisraʾel Synagogue. An archaeological investigation of the site followed, which lasted until 2020. When it is completed in historical form, the Tifferet Jisraʾel Synagogue will be the tallest building in Jerusalem's Old City.

The Elijahu Synagogue, also known as Tzemach Tzedek ChaBaD , was founded in 1858 by Lubavitcher Hasidim. It was closed during the First World War, then looted. After 1948 the building remained undamaged because a Palestinian set up a weaving mill here. After 1967 the Hasidim returned; In 1971 the synagogue and Kollel were formally inaugurated.

Archaeological zones and museums

The reconstruction was preceded by the archaeological exploration of the quarter. The Upper City of Jerusalem was located on the area of the Jewish Quarter at the time of the Second Temple . The first excavation began in 1969 under the direction of Nahman Avigad ( Hebrew University of Jerusalem ), and in three campaigns by 1971 nine areas, about 20% of the Jewish Quarter in total, were excavated. There were spectacular finds of the ancient Jewish city in an area that was already assigned to the Yeschivat haKotel (Wohl Torah Center). As a compromise, an underground museum of the excavation findings was created and above it, supported by concrete pillars, the new building of the yeshiva. According to Ricca, archeology had a legitimizing function for the redevelopment of the Jewish Quarter, because it made it possible, far in the past, to connect to a Jerusalem that was clearly Jewish, far behind a neglected and Arab-looking building. It is therefore also made visible in the cityscape, e.g. B. the wide wall excavated by Avigad from the Iron Age or the time of the southern kingdom of Judah . In order to present a 40 m long, approximately 7 m wide segment of this ground monument, which is important for Israel's history, existing development plans were revised. The underground museums Herodian Quarter and House of the Qathros Family bring visitors to the Jewish Quarter closer to the Roman conquest of Jerusalem in AD 70.

In the excavation area of the Cardo, the boulevard of Byzantine Jerusalem dominates the picture; But there are also remains of walls and gates of the Iron Age and Hellenistic city as well as a shopping street from the time of the Crusaders.

The archaeological area of the Crusader Church of St. Maria Alemannorum was designed as a garden after the excavations were completed and opened to the public in 1975.

In the south-west corner of the Jewish Quarter, the archaeological findings were in a park ( Hebrew גן התקומה Gan haTekuma , “Garden of Reconstruction”). Earlier archaeologists had already worked here, and their findings were rediscovered as part of the old town excavations. Essentially, it is the Byzantine Nea church with outbuildings. The huge cistern was incorporated into a bathhouse from the crusader era; there are also remains of a Fatimid crusader period city wall and an Ayjubid gate tower. After years of neglect, the ruins of the Nea Church are no longer open to the public.

In the course of the demographic changes towards an ultra-Orthodox residential area, there was also a shift in emphasis in the presentation of the archaeological finds in the district: the archaeological zone of the Crusader Church was given the supervision of the EschhaTora yeshiva, who installed a mezuzah at the entrance and provided information about it removed that it was a former church. In the area of the Cardo, a monumental replica of the menorah of the Herodian Temple was erected, which has no connection with the Cardo as the boulevard of the Byzantine and Crusader-era city.

Outside the southern old town wall is the Archaeological Park with the Davidson Center, which in a broader sense can also be viewed as part of the Jewish Quarter. This park was opened to the public in 1982 under the name Yitzhak Ben Youssef Levy Garden - The Ophel and in 1999 it was incorporated into the larger Ophel Archaeological Park .

Other museums and memorials

- The Isaac Kaplan Old Yishuv Court Museum , Rechov Or Hachaim 6: Shows the continuity of Jewish life in the old city of Jerusalem over 500 years until the Jordanian conquest in 1948 with historical home furnishings and everyday objects.

- Ariel - Center for Jerusalem in the First Temple Period , Rechov Bonei Hachoma 7: Small interactive museum showing a model of Jerusalem at the time of the First Temple (before 587/86 BC) and exhibits (replicas) related to this period. It is directed by Jad Ben Zvi , an educational institution for Land Israel Studies under the supervision of the Ministry of Education.

- Temple Institute ( The Mikdash Educational Center of Machon HaMikdash ), Rechov Misgav Ladach 40: Visitor center with replicas of cult implements and priestly robes from the Jewish temple; Study facility (Kollel) that researches the temple cult; Academy for Jewish Priests .

- The Chain of Generations Center : Access is from Western Wall Plaza, for groups only. Multimedia, experience-oriented communication of 3000 years of history of the Jewish people and their connection with Jerusalem. Eight underground themed rooms with modern installations; In one room, archaeological finds from the time of the First Temple can be viewed through the glass floor. The museum is run by the Western Wall Heritage Foundation .

- Plugat HaKotel Museum (new since May 2018): Dedicated to a group of 24 Betar activists who moved into a house in the Jewish Quarter during the British Mandate to protect Jews from Arab attacks and to undermine measures by the British Mandate Government, such as the ban to blow the shofar on the western wall.

- Jewish Quarter Defender's Memorial : Photo exhibition with historical photos of the fight for Jerusalem during the Palestine War. The memorial is located on the site of a mass grave for 37 fighters and 30 residents who were buried near the Batei-Machse building complex in 1948, but exhumed in 1967 and buried with a military ceremony at the Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives .

literature

- Doron Bar, Rehav Rubin: The Jewish Quarter after 1967: A Case Study on the Creation of an Ideological-Cultural Landscape in Jerusalem's Old City . In: Journal of Urban History 37 5/2011, pp. 775-792. ( PDF )

- Johannes Becker: Locations in the old city of Jerusalem: life stories and everyday life in a narrow urban space . transcript, Bielefeld 2017.

- Michael Dumper: Jerusalem Unbound: Geography, History, and the Future of the Holy City . Columbia University Press, New York 2014.

- Matti Friedman: From blank slate to theme park, Jerusalem's Jewish Quarter still seeks an identity . In: The Times of Israel , May 18, 2012.

- Nir Hasson: Jerusalem Old City's Jewish Quarter Almost Entirely Haredi, Study Finds . In: Haaretz , June 10, 2011.

- Susan Hattis Rolef: The Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem . In: architecture of israel quarterly, No. 39 (autumn 1999).

- Ruth Kark, Michal Oren-Nordheim: Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948 . Magnes Press, Jerusalem 2001.

- Max Küchler : Jerusalem: A Handbook and Study Guide to the Holy City . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, pp. 552–601.

- Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 . Tauris, New York 2007.

- Alexander Schölch : Jerusalem in the 19th century (1831–1917 AD) . In: Kamil Jamil Asali (ed.): Jerusalem in history . Olive Branch Press, New York 1990, pp. 228-248.

Web links

- The Company for the Reconstruction and Development of the Jewish Quarter in the Old City of Jerusalem Ltd .: own website

Individual evidence

- ^ The Company for the Development and the Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter in the Old City of Jerusalem Ltd .: Company Profile - General Overview .

- ↑ Heddy Breuer Abramowitz: Jewish, Armenian Old City neighbors unite to contest renovation plans . In: The Jerusalem Post , September 9, 2019.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 552 f.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A Handbook and Study Travel Guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 1110.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, pp. 553–559.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, pp. 559-561.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, pp. 1117–1119.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, pp. 561-563.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 157 f.

- ^ Katharina Galor , Hanswulf Bloedhorn: The Archeology of Jerusalem: From the Origins to the Ottomans . Yale University Press, New Haven / London 2013, p. 180 f.

- ↑ Ruth Kark, Michal Oren-Nordheim: Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948 , Jerusalem 2001, pp. 44 f.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 593 f.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, pp. 1121–1123.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, pp. 589-592. 1127.

- ↑ Terrestrial Jerusalem: Sidna Umar Mosque מסגד סידנא עומר, مسجد سيدنا عمر .

- ^ Francis Edward Peters : Jerusalem: The Holy City in the Eyes of Chroniclers, Visitors, Pilgrims, and Prophets from the Days of Abraham to the Beginnings of Modern Times . Princeton University Press, Princeton 1985, pp. 357-359.

- ^ Dotan Arad: When the Home Becomes a Shrine: Public Prayers in Private Houses among the Ottoman Jews . In: Marco Faini, Alessia Meneghin (Ed.): Domestic Devotions in the Early Modern World . Brill, Leiden et al. 2019, pp. 55–68, here p. 59.

- ^ Dotan Arad: When the Home Becomes a Shrine: Public Prayers in Private Houses among the Ottoman Jews . In: Marco Faini, Alessia Meneghin (Ed.): Domestic Devotions in the Early Modern World . Brill, Leiden et al. 2019, pp. 55–68, here p. 62.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 168 f.

- ↑ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 18 f.

- ↑ Ira Sharkansky: Governing Jerusalem: Again on the World's Agenda . Wayne State University Press, Detroit 1996, p. 69.

- ↑ Ruth Kark, Michal Oren-Nordheim: Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948 , Jerusalem 2001, p. 55.

- ↑ Ruth Kark, Michal Oren-Nordheim: Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948 , Jerusalem 2001, p. 66.

- ↑ a b Ruth Kark, Michal Oren-Nordheim: Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948 , Jerusalem 2001, p. 68.

- ^ Yair Wallach: Jewish nationalism: On the (im) possibility of Muslim Jews . In: Josef Meri (ed.): The Routledge Handbook of Muslim-Jewish Relations , New York 2016, pp. 331-350, here pp. 336 f.

- ↑ Ruth Kark, Michal Oren-Nordheim: Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948 , Jerusalem 2001, pp. 68 f.

- ↑ Ruth Kark, Michal Oren-Nordheim: Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948 , Jerusalem 2001, p. 65.

- ↑ Ruth Kark, Michal Oren-Nordheim: Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948 , Jerusalem 2001, pp. 60 f.

- ↑ Ruth Kark, Michal Oren-Nordheim: Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948 , Jerusalem 2001, p. 70.

- ↑ Ruth Kark, Michal Oren-Nordheim: Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948 , Jerusalem 2001, p. 69.

- ^ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 20.

- ↑ a b Terrestrial Jerusalem: "Batei Machse" בתי מחסה, باتى محسى

- ^ Reuven Gafni: Jewish Sacred Architecture in the Ottoman Empire . In: Steven Fine (Ed.): Jewish Religious Architecture: From Biblical Israel to Modern Judaism . Brill, Leiden / Boston 2020, pp. 238–257, here p. 245.

- ↑ Nadav Shragai: Out of the ruins. After nearly 40 years of architectural discussions, the famous Hurva Synagogue in Jerusalem's Old City is to be rebuilt . In: Haaretz, December 20, 2005.

- ↑ Johannes Becker: Locations in the Jerusalem old town: life stories and everyday life in a narrow urban space , Bielefeld 2017, p. 118.

- ↑ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, pp. 20 f. Johannes Becker: Locations in the Old City of Jerusalem: Life stories and everyday life in a narrow urban space , Bielefeld 2017, p. 266 f.

- ↑ a b c d e f Matti Friedman: From blank slate to theme park, Jerusalem's Jewish Quarter still seeks an identity . In: The Times of Israel , May 18, 2012.

- ↑ a b c Johannes Becker: Locations in the Jerusalem old town: life stories and everyday life in a narrow urban space , Bielefeld 2017, p. 266 f.

- ↑ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 37 f.

- ^ Jean-François Pitteloud: Ruegger, Paul. In: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz ., Accessed on April 11, 2017.

- ↑ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, pp. 20-22.52. Johannes Becker: Locations in the Old City of Jerusalem: Life stories and everyday life in a narrow urban space , Bielefeld 2017, p. 86.

- ↑ How much pressure was exerted is shown differently in the literature, depending on the political orientation. Cf. Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 52 f.

- ^ A b Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 49.

- ↑ Tamar Katriel: Performing the Past: A Study of Israeli Settlement Museum . Routledge, New York 2009, p. 153.

- ^ Yair Wallach: Jewish nationalism: On the (im) possibility of Muslim Jews . In: Josef Meri (Ed.): The Routledge Handbook of Muslim-Jewish Relations , New York 2016, pp. 331-350, here pp. 333 f.

- ^ Nir Hasson: State Company Trying to Evict Evangelical Christian From Jerusalem's Jewish Quarter . In: Haaretz, May 9, 2011.

- ^ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 48.

- ↑ Later the architects Nechemia Bikson and Yoel Bar-Dor joined the management team, twelve other architects worked on the reconstruction of the Jewish quarter, including Ronit Soan, Noga Landver, Uri Ponger, Yoel Shoham, Max Loterman, Jonathan Shiloni, Claude Rosenkovitch and David Bar. Safdie, Yaar, Frankel, Tanai, Schoenberg, Kalman Katz, Marco, Best and Tamir planned the reconstruction of individual buildings as architects. See Susan Hattis Rolef: The Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem , Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, pp. 75 f.

- ↑ Kobi Cohen-Hattab, Noam Shoval: Tourism, Religion and Pilgrimage in Jerusalem . Routledge, London / New York 2015, p. 139.

- ↑ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 39.

- ^ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 83.

- ^ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 84.

- ↑ Kobi Cohen-Hattab, Noam Shoval: Tourism, Religion and Pilgrimage in Jerusalem . Routledge, London / New York 2015, p. 139 f.

- ↑ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 6.

- ^ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 81.

- ↑ a b Susan Hattis Rolef: The Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem . In: architecture of israel quarterly, No. 39 (autumn 1999).

- ↑ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 42.44.

- ↑ Quoted from: Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 77.

- ↑ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, pp. 60 f.

- ^ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 79.

- ↑ Eyal Weizman: Hollow Land: Israel's Architecture of Occupation . Verso, London / New York 2007, p. 44.

- ↑ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, pp. 84-86.

- ↑ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 86 f.

- ↑ Terrestrial Jerusalem: The Jewish Quarter Community Center מתנ"ס הרובע היהודי, مركز اجتماعي- الحي اليهودي .

- ↑ Terrestrial Jerusalem: Library- Jewish Quarter ספריית הרובע היהודי, مكتبه- الحي اليهودي .

- ^ Terrestrial Jerusalem: Educational institutions - Jewish quarter .

- ^ Jerusalem Foundation, Projects: Jewish Quarter Elementary School .

- ↑ a b Terrestrial Jerusalem: Porat Yosef Yeshiva ישיבת פורת יוסף, المدرسة الدينية بورات يوسف (يشيفا )

- ↑ a b Yeshiva University: Guide to Israel Schools - HaKotel

- ↑ Terrestrial Jerusalem: Hakotel Yeshiva ישיבת הכותל, هكوتىل يشيفا ; Dormitory and Residential Complex for Scholars מתחם מגורי אברכים ופנימייה .

- ^ Yeshiva University: Guide to Israel Schools - Gesher Aish HaTorah

- ↑ Aish HaTorah: Our Story

- ^ Yeshiva University: Guide to Israel Schools - Netiv Aryeh

- ↑ YNA: About

- ↑ Terrestrial Jerusalem: Hayei Olam Yeshiva ישיבת חיי עולם, يشيفا الحياة اولم

- ↑ Midreshet HaRova: Our Campus

- ↑ Doron Bar, Rehav Rubin: The Jewish Quarter after 1967: A Case Study on the Creation of an Ideological-Cultural Landscape in Jerusalem's Old City , 2011 S. 783rd

- ↑ Terrestrial Jerusalem: Sapir Jewish Heritage Center מרכז ספיר, مركز سابير- مدرسة عسكرية

- ^ Nir Hasson: Jerusalem Old City's Jewish Quarter Almost Entirely Haredi, Study Finds . In: Haaretz , June 10, 2011.

- ↑ Uzi Benziman: Ticking Time Bomb in Jewish Quarter . In: Haaretz, May 24, 2006.

- ↑ a b c Ira Sharkansky: Governing Jerusalem: Again on the World's Agenda . Wayne State University Press, Detroit 1996, p. 80.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research: Jerusalem Statistical Yearbook

- ↑ XVI / 21 Electoral Results for the 19th Knesset in Jerusalem, by Quarter and Sub-Quarter, January 2013

- ^ Electoral Results for the 20th Knesset in Jerusalem, by Quarter and Sub-Quarter, March 2015

- ↑ Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Press Release 2015: 3.3 million visitors to Israel in 2014 .

- ^ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 88.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A Handbook and Study Travel Guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 597.

- ↑ Doron Bar, Rehav Rubin: The Jewish Quarter after 1967: A Case Study on the Creation of an Ideological-Cultural Landscape in Jerusalem's Old City , 2011 S. 781st

- ↑ Terrestrial Jerusalem: The Ramban Synagogue - Nahmanides בית כנסת הרמב"ן, كنيس هرامبان .

- ↑ Prime Minister's Office, Press release: Cabinet Makes Series of Decisions to Strengthen Jerusalem and Assist in its Economic, Tourist, Cultural and Social Development , May 28, 2014.

- ↑ This Week in Jerusalem: Even at Safra Square . In: The Jerusalem Post, March 19, 2020.

- ↑ Terrestrial Jerusalem: Eliyahu (Chabad) Synagogue בית כנסת אליהו מנחם - חב"ד, كنيس إلياهو حباد .

- ↑ Kobi Cohen-Hattab, Noam Shoval: Tourism, Religion and Pilgrimage in Jerusalem . Routledge, London / New York 2015, pp. 140 f.

- ^ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 36.

- ↑ Simone Ricca: Reinventing Jerusalem: Israel's Reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967 , New York 2007, p. 72. Cf. Max Küchler: Jerusalem: Ein Handbuch und Studienreisführer zur Heiligen Stadt , Göttingen 2007, p. 574: “Der archäol. Digging shows only the Israelite. Time ... because all later layers have been cleared away or built over. "

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, pp. 522-526.

- ^ The Jerusalem Foundation, Projects: St. Mary's of the German Knights .

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, pp. 526-534.

- ^ Matti Friedman: From blank slate to theme park, Jerusalem's Jewish Quarter still seeks an identity . In: The Times of Israel , May 18, 2012.

- ↑ Doron Bar, Rehav Rubin: The Jewish Quarter after 1967: A Case Study on the Creation of an Ideological-Cultural Landscape in Jerusalem's Old City , 2011 S. 788th

- ↑ The Jerusalem Foundation, Projects: Ophel Archeological Park (Yitzhak Ben Youssef Levy Garden-The Ophel)

- ^ The Isaac Kaplan Old Yishuv Court Museum: The Museum .

- ^ The Jerusalem Foundation, Projects: Ari'el Center for Jerusalem in the First Temple Period .

- ↑ Terrestrial Jerusalem: Ariel Center מרכז אריאל, مركز ارييل

- ↑ Terrestrial Jerusalem: The Temple Institute in Jerusalem מכון המקדש

- ↑ Wendy Pullan, Maximilian Sternberg, Lefkos Kyriacou, Craig Larkin, Michael Dumper: The Struggle for Jerusalem''s Holy Places . Routledge, London / New York 2013, p. 38 f.

Coordinates: 31 ° 47 ' N , 35 ° 14' E