Herodian temple

Herod the Great began in 21 BC. With a fundamental redesign of the Jerusalem temple , which also became his most demanding building project. The actual temple building was completed within just a year and a half and inaugurated with great splendor. The redesign of the entire Temple Mount complex, however, dragged on long after Herod's death and was only completed shortly before the outbreak of the Jewish War . It was destroyed by the Roman army in 70 AD .

Building description and cult operation

Every reconstruction of the Herodian Temple is a combination of the information in Flavius Josephus ( Jüdische Antiquities 15, 380-423; Jüdischer Krieg 5, 184-243) and in the Talmud (especially the Mishnah tract of Middot). "The differences in the sources can probably be traced back to the different building phases of the temple - before Herod, under Herod, after Herod, before the temple was destroyed."

Josephus was interested in the entire temple area including the forecourt of the heathen with circumferential porticos to the north, west and east and a basilica on the south side, while the Mishna was primarily interested in the area within the balustrade ( Hebrew סורג Soreg ) describes that only members of the Jewish religious community were allowed to enter in a state of cultic purity and that is shown on the following map.

Description of the temple building based on the ocher colored point .

This point stands for a sink in the so-called forecourt of the priests ( Hebrew עזרה Azara ). A viewer standing by the sink looked north at a wide staircase that led up to the temple house. Looking west , he saw the facade of the temple house; to the east he saw a wide ramp that led up to the great burnt offering altar.

The rectangular complex occupied the highest point of the Temple Mount and stood on a platform, partly made of natural rock and partly heaped up, which was about 3 to 4 meters higher than the forecourt of the heathen.

Pronaos

The width of the entrance area ( pronaos , Hebrew אולם Ulam ) compared to the sanctuary, according to Mishnah (Middot IV, 7), the building looked like a resting lion: broad in front, narrower in the back. The facade was extremely high, so that it had to be stabilized with beams, and the entrance portal was also very high; it represented the most important light source for the inner rooms. The sources give less information about the external appearance of the temple house and contradict each other, which can explain the different reconstructions by model makers. Josephus and Mishnah unanimously mention one detail: golden spikes on the roof, which the Mishnah calls them "warding off crows."

Naos

The sanctuary was entered through a double door. It had a front section ( Hebrew היכל Hechal ), where the menorah, the showbread table and the incense altar were (marked with small dots in the plan ), and a roughly square, empty room to the west : the Holy of Holies, divided by two overlapping curtains ( Hebrew דביר Debir ). Architecturally, Hechal and Debir formed a unit ( Naos ). They shared an upper floor, from where necessary repairs in the sanctuary could be carried out through openings in the floor so that the craftsmen had as little contact as possible with the sacred areas.

Once a year, on the Day of Atonement ( Hebrew יוֹם כִּפּוּר 'Day of Atonement' ), the high priest entered the holy of holies .

The daily priestly activities in the Hechal , namely operating the candlestick, placing the showbread on the showbread table and offering the incense, formed the first cultic focus of the Jerusalem temple and were not visible to normal temple visitors.

There were chambers around Hechal and Debir ( Hebrew תאים Ta'im ) on several floors, in which, among other things, the temple treasures were deposited.

Priest's Courtyard

Starting from the ocher-colored location again , a few meters to the east you could see the already mentioned wide ramp that led up to the altar of burnt offerings. This altar was a great podium.

To the north of the burnt offering altar were the slaughtering places for the sacrificial animals, arranged in rows.

A little further to the east one saw a barrier up to which Jewish men in a state of cultic purity were allowed to go to watch the acts of sacrifice. The narrow area in which they were allowed to stand was the so-called forecourt of the Israelites (Hebrew עזרת ישראל Ezrat Yisrael ).

The animal sacrifices in the priestly court formed the second cultic focal point of the Jerusalem temple. Although they were not accessible to laypeople, they were (to a limited extent) visible.

Women's atrium

To the east of the priest's forecourt with the temple house on it was connected to a large square forecourt. This so-called women's forecourt ( Hebrew עזרת נשים Ezrat Naschim ) was essentially the place where the crowd of Jewish pilgrims gathered. According to the sources, there was a kind of wraparound balcony on which only women were allowed to stay.

In the four corners there were divided, upwardly open areas, which are known as chambers or courtyards:

- Southeast: Contact point for people who had taken a Nazarite vow. Here they prepared the sacrifice prescribed for them.

- Northwest: Contact point for people who have been healed from leprosy . They found a mikveh here , in which they cleaned themselves.

- Northeast: Depot for wood.

- Southwest: depot for wine and oil.

The passage to the forecourt of the Israelites was highlighted architecturally. The entrance was a triple portal , the so-called Nikanortor , and was particularly valuable . The semicircular staircase that led up to him had fifteen steps on which the Levites played music. As these chants were seen by many temple visitors, they later became part of the synagogue liturgy. In contrast, it is largely unknown what was sung or recited during the cult activities in the temple itself.

destruction

During the Jewish-Roman war, the temple was held by the defenders until the end, and when it was captured by the Roman legionaries in August 70 AD, it was set on fire and looted. As a chronicler of these events, Flavius Josephus wants to absolve the Roman commander and later Emperor Titus of responsibility. In contrast to the First Temple, there are individual finds from the temple grounds as well as remains of the building fabric in and in front of the surrounding walls.

archeology

Temple grounds

Since archaeological research is not possible on the temple grounds, it is also not known whether there are any remains of the Herodian temple there. This is not ruled out, as early photographs presumably show ancient building fabric. But in the 20th century the Waqf authorities carried out larger, archaeologically unattended construction work on the area. DM Jacobson and Sh. Gibson identified on plans, engravings and photographs from 1833 to 1870 to the right of the staircase that leads up to the Dome of the Rock from the south, four steps of a Herodian staircase at least 34 meters wide, which today has disappeared or is covered by vegetation.

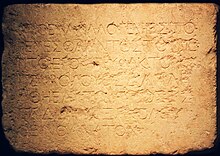

Two limestone blocks with Greek warning inscriptions , which were embedded in the balustrade (Soreg) around the inner temple area, were found as spoils north of the Temple Mount and near the Lion Gate.They are now in the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul and in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem .

A spoil found in a pool of water filled with rubble from the year 70 bears a fragmentary Greek foundation inscription for a floor covering from the 20th year of Herod (18/17 BC). This artifact is on display at the Hecht Museum in Haifa .

Architectural fragments and small finds that could be assigned to the Herodian basilica were found in the rubble below the southern wall. Among them are pieces of Corinthian capitals with remnants of gold leaf decoration, which correspond to the description of the building by Josephus.

The findings of the Temple Mount Sifting Project , the scientific value of which is controversial, included pieces of a very colorful pavement using the Opus-sectile technique, which was presented to the public on September 8, 2016. In Gabriel Barkay's opinion, this is how the floor in the temple courtyards was laid shortly before the Jewish War .

Enclosing walls

Beforeodian (Seleucid, Hasmonean) masonry is only recognizable in the eastern perimeter wall. In particular, the stone layers of the Herodian temple can be clearly seen within the surrounding walls. "The very well-crafted mirror cubes with hem are 1–1.2 m, in some cases even 1.9 m high and reach lengths of up to 11 m."

Particularly noteworthy is an inscribed stone with the dimensions 31 × 86 × 26 cm, which bears the Hebrew inscription "For the place of the trumpet signal". He was at the top of the wall at the south-west corner and, when the temple was destroyed, fell onto the paved road that ran beneath the wall. There it was discovered and published by Benjamin Mazar in 1970. "Since the priests may have known where the trumpet chime was, the purpose of this inscription is formal or ceremonial rather than practical." The find is on display at the Israel Museum today.

Accesses

Except in the north, large stairs and bridges were necessary to bring visitors from Jerusalem street level to the Herodian temple plateau. The two Hulda gates were on the south side. According to the Mishnah, there was the Shushan Gate on the east side, which may have been located on the site of today's Golden Gate. Four entrances are known on the west side, which are named after researchers of the 19th century. They are identical to those described by Josephus. From North to south:

- Warren Gate (after Charles Warren ). Only a part of the southern door post remains of the Herodian gate system.

- Wilson bow (after Charles William Wilson ). Herod already had a representative double gate built as the western entrance to the temple square when he was expanding his temple, where the two gates Bab as-Silsila and Bab as-Sakina are located. Flavius Josephus wrote that a bridge led from the Xystos (probably the name of a hypostyle hall) to the western hypostyle hall of the temple; the bridge was the Wilson Arch, built in Herodian times. Fighting took place several times during the Jewish War at this strategically important entrance to the temple area , and, as research has long assumed, the Wilson Arch was also destroyed. "Although the arch in its current form was only dated to early Islamic times (Bieberstein / Bloedhorn, 1994, III, 404-406; Bahat, 2013, 28.79-86), it can now be identified with Onn, Weksler-Bdolah and Bar-Nathan ( 2011) can already be convincingly attributed to the Herodian western expansion of the platform. 1991–1992 the uppermost steps of a monumental access staircase from the same time came to light on the square in front of Bāb es-Silsila and Bāb es-Sakīna (Kogan-Zehavi, 1997) finally that there were two phases of construction: the first at the time of Herod or shortly after his death and a second between the years 30 and 60 AD, when the entrance was widened to around 15 meters.

- Barclay Gate (after James Turner Barclay ). From the plaza of the Western Wall one half of the large Herodian lintel and the secondary stone filling of the gate opening are visible.

- Robinson bow (after Edward Robinson ). The wedge stones in the 11th layer of the Herodian surrounding wall have been preserved. These are fitted into the Herodian masonry on both sides without breaking. "The advancing stones below the arch base possibly served as supports for the scaffolding."

Web links

- Israel Museum: Public Buildings Built by Herod in Jerusalem . Video, close-up views of all Herodian buildings in the model.

- Markus Sasse: Jesus in Jerusalem. A search for clues. Online material RPH 2-2018 "The time and the world of Jesus" ( PDF 2.8 MB; 45 pages on bildungsnetz.bildung-rp.de)

literature

- Meir Ben-Dov: Herod's Mighty Temple Mount. In: Biblical Archeology Review 12, 6/1986; cojs.org

- Theodor A. Busink: The Temple of Jerusalem. From Solomon to Herod - an archaeological-historical study taking into account the Western Semitic temple construction. Volume 1, Leiden 1970; Volume 2, Leiden 1980.

- Hannah M. Cotton et al. (Ed.): Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae / Palaestinae . Volume 1: Jerusalem. Part 1. De Gruyter, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-022219-7 .

- Katharina Galor : To the glory of God and the King. The Temple of Jerusalem. In: World and Environment of the Bible 4/2013, pp. 58–61.

- Simon Goldhill : The Temple of Jerusalem. Harvard University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-674-01797-8 .

- Antonius HJ Gunneweg: History of Israel. From the beginning to Bar Kochba and from Theodor Herzl to the present. Kohlhammer, 6th edition, Stuttgart 1989. ISBN 3-17-010511-6 .

- Johannes Hahn: Destruction of the Jerusalem Temple: Events - Perception - Coping ( Scientific Investigations on the New Testament 147). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2002. ISBN 3-16-147719-7 .

- Max Küchler : Jerusalem. A handbook and study guide to the Holy City. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-50170-2 .

- Roger Liebi : The Messiah in the Temple. Symbolism and meaning of the Second Temple in the light of the New Testament. Christian literature distribution , Bielefeld 2003, ISBN 3-89397-641-8 bitimage.dyndns.org (PDF).

- Johann Maier : Between the wills. History and Religion in the Time of the Second Temple (The New Real Bible, Supplementary Volume 3 to the Old Testament). Echter, Würzburg 1990. ISBN 3-429-01292-9 .

- Ehud Netzer : The Architecture of Herod, the Great Builder. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2006, ISBN 978-0-8010-3612-5 .

- Helmut Schwier : Temple and Temple Destruction. Investigations into the theological and ideological factors in the first Jewish-Roman war (66–74 AD). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1989, ISBN 3-525-53912-6 .

- Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina: The Roman Policy towards the Jews from Vespasian to Hadrian . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2016. ISBN 978-3-647-20869-5 .

- Charles W. Wilson: Ordinance Survey of Jerusalem , 1886 ( templemount.org ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Katharina Galor: To the glory of God and the king . 2013, p. 59 .

- ↑ a b c Ehud Netzer: Architecture of Herod . 2006, p. 140 .

- ↑ a b Ehud Netzer: Architecture of Herod . S. 138 .

- ^ Ehud Netzer: Architecture of Herod . S. 142 .

- ^ Ehud Netzer: Architecture of Herod . S. 148 .

- ^ Ehud Netzer: Architecture of Herod . S. 152 .

- ↑ a b Ehud Netzer: Architecture of Herod . S. 149 .

- ^ Ehud Netzer: Architecture of Herod . S. 143 .

- ^ Ehud Netzer: Architecture of Herod . S. 146-147 .

- ↑ a b Johann Maier: Between the wills . S. 227 .

- ^ Ehud Netzer: Architecture of Herod . S. 154 .

- ↑ a b Ehud Netzer: Architecture of Herod . S. 160 .

- ↑ Johann Maier: Between the wills . S. 233-234 .

- ^ Antonius HJ Gunneweg: History of Israel . S. 190 .

- ^ Simon Goldhill: The Temple of Jerusalem . S. 17 .

- ↑ Johannes Hahn , Christian Ronning (Ed.): Destruction of the Jerusalem Temple. Events - perception - coping. Scientific research on the New Testament, Volume 147, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-16-147719-7 , (manuscript) stefanluecking.de (PDF).

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-50170-2 , pp. 307 .

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-50170-2 , pp. 236 .

- ^ Hannah M. Cotton: Corpus Inscriptionem Iudaeae / Palaestinae . S. 45-47 .

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-50170-2 , pp. 282-283 .

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-50170-2 , pp. 281 .

- ↑ Archeologists restore flooring from Second Temple courtyard in Jerusalem. In: Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. September 8, 2016, accessed May 6, 2018 .

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-50170-2 , pp. 152 .

- ↑ Monika Bernett: The imperial cult in Judea under the Herodians and Romans: Investigations into the political and religious history of Judea from 30 BC. to 66 AD Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2007, p. 156 .

- ^ Hannah M. Cotton: Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae / Palaestinae . S. 50 .

- ^ Ehud Netzer: Architecture of Herod . S. 173-174 .

- ^ Ehud Netzer: Architecture of Herod . 2006, p. 131 .

- ^ Ehud Netzer: Architecture of Herod . 2006, p. 172-173 .

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-50170-2 , pp. 166 .

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-50170-2 , pp. 160 (According to Flavius Josephus: πύλαι, "gates").

- ↑ Flavius Josephus: Jewish War . tape 2 , no. 344 .

- ↑ Alexander Onn, Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah, Rachel Bar-Nathan: Jerusalem, The Old City, Wilson's Arch and the Great Causeway (Preliminary Report). In: Hadashot Arkheologiyot. Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Israel Antiquities Authority, August 15, 2011, accessed October 21, 2018 .

- ↑ Johanna Regev, Joe Uziel, Tehillah Lieberman and others: Radiocarbon dating and microarchaeology untangle the history of Jerusalem's Temple Mount: A view from Wilson's Arch . In: PLOS ONE, June 3, 2020, accessed on June 5, 2020.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-50170-2 , pp. 173 .

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-50170-2 , pp. 296 .