Temple Mount Sifting Project

The Temple Mount Sifting Project was an initiative that examined excavated soil from the Jerusalem Temple Mount for small finds it contained. The importance of this project arises from the fact that archaeological research is not possible on the Temple Mount.

The excavated soil, around 400 truckloads, was incurred during the construction of an access ramp to the underground Marwani Mosque and was piled up in the Kidron Valley. Zachi Dvira, then an archeology student, removed some ancient objects from the rubble and in this way made known what could possibly be found here. Gabriel Barkay , one of Dvira's lecturers at Bar Ilan University , got involved in the project. The two succeeded in relocating the excavated soil in 2004 from the landfill to the Emek-Zurim National Park in the Kidron Valley (which is practically identical to the facilities of the Temple Mount Sifting Project ) and began its investigation on a small scale.

Then the right-wing Elad Foundation , which also runs the City of David National Park , got involved, apparently because it fit their agenda. (This non-profit organization aims to establish a Jewish presence in the Palestinian town of Silwan . The name אלע"ד Elad is an acronym for Hebrew: אל עיר דוד El Ir David , "towards the city of David".) With Elad's funding won the Temple Mount Sifting Project added a new dimension.

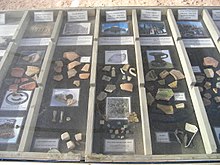

Since 2005, almost 200,000 volunteers have been busy sieving the material in a process similar to gold washing after a brief briefing. Since the finds were mixed with a lot of dust and ash, water was added during the sifting process after an initial check of the dry excavation. This made it easier to separate a small find from adhering soil. Findings were sorted into six categories: ceramics, glass, bones and shells, tesserae , metal, special stones and stucco. Special finds such as coins should be documented and taken into safekeeping immediately by employees. During their visits to the Emek-Zurim National Park, employees of the NGO Emek Shaveh observed that the excavated soil to be screened was definitely accessible if someone wanted to manipulate something, and that the (paying) volunteers were only accompanied by semi-skilled workers in their work. Professional archaeologists were not found.

As archaeologists, it was clear to Barkay and Dvira that by losing their context, the finds had lost most of their meaning that they could have had in a regular excavation. Barkay thought it possible to partially compensate for this by comparing the finds with similar objects, the context of which was known. Emek Shaveh commented critically that there was no guarantee that the rubble seized at the landfill came entirely from the construction work in the area of the Marwani Mosque or the Temple Mount. In addition, extensive renovations had taken place on the Temple Mount in the 20th century, during which shards and other small objects could first find their way onto the Temple Mount and then into the excavated earth investigated by the Temple Mount Sifting Project .

While sifting is part of the daily work of archaeologists, this is usually embedded in the context of the excavation and is carried out by the excavation participants themselves, so that no outsider can remove or add objects. As with the Temple Mount Sifting Project, earth is seldom sifted through without digging. An example of a parallel approach was the investigation of the rubble from the necropolis of Umm el-Qaab .

In 2017, after twelve years and after around 70% of the excavation had been examined, the Elad Foundation suddenly stopped supporting it. Since then, private donations have been used to finance a small group of researchers who want to evaluate and publish the material found so far.

In its criticism of the project, the NGO Emek Shaveh comes to the conclusion that the scientific value of the Temple Mount Sifting Project , which both the Israeli Antiquities Authority and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority emphasize, is low because archaeological standards are not maintained and it is little more than a leisure activity for volunteers. This ultimately supports the political agenda of the Elad Foundation. Even Catherine Galors opinion on the project falls negative: the finds missing its context, the rubble had been relocated twice, and the proceedings have no scientific value.

Web links

- Own homepage of the project

- Emek Shaveh (NGO): Archeology on a Slippery Slope: Elad's sifting project in Emek Tzurim National Park , September 13, 2013.

- Daniel K. Eisenbud: Rare 3,000-year-old King David Era Seal Discovered by Temple Mount Sifting Project . In: The Jerusalem Post, September 24, 2015.

- Danna Harman: Uncovering Jerusalem's History in the Rubble of Temple Mount . In: Haaretz, October 28, 2015.

- Carl Hoffman: Temple Mount Sifting Project at a Crossroad . In: The Jerusalem Post, July 20, 2017.