Tel Aviv-Jaffa

| Tel Aviv-Jaffa | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| Basic data | |||

| hebrew : | תל אביב-יפו | ||

| State : |

|

||

| District : | Tel Aviv | ||

| Founded : | 1909 | ||

| Coordinates : | 32 ° 5 ' N , 34 ° 48' E | ||

| Area : | 51.830 km² | ||

| Residents : | 451,523 (as of 2018) | ||

| Population density : | 8,712 inhabitants per km² | ||

| - Metropolitan area : | 3,850,100 (2017) | ||

| Community code : | 5000 | ||

| Time zone : | UTC + 2 | ||

| Telephone code : | (+972) 3 | ||

| Postal code : | 61000-61999 | ||

| Community type: | Big city | ||

| Mayor : | Ron Huldai | ||

| Website : | |||

|

|

|||

Tel Aviv-Jaffa ( Hebrew תֵּל־אָבִיב – יָפוֹ Tel Avīv-Jafō , Tel-Aviv means spring hill , a historical name of Jaffa is Joppe ), often just Tel Aviv , is a large city in Israel .

Tel Aviv, founded in 1909, was originally a suburb of the port city of Jaffa, which has existed since ancient times . In 1950 both cities were united to what is now Tel Aviv-Jaffa . The metropolitan area of the city, the Gush Dan , has a total of about 254 parishes and more than 3 million inhabitants, which corresponds to around a third of the total Israeli population. Today the city is considered the economic and social center of the country, was initially the de facto seat of government after the founding of the state of Israel and today still counts almost all foreign embassy seats. The city is also home to the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange and Tel Aviv University .

Tel Aviv is one of the largest economic centers in the Middle East. The White City , which was largely built in the Bauhaus style and the world's largest center of buildings in the international style , has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2003 .

The name "Tel Aviv"

The name "Tel Aviv" is borrowed from a poetic translation of the title of the utopian novel Altneuland by Theodor Herzl . In it, “ Tel ” (multi-layered settlement hill) stands for “old” and “Aviv” (spring) for “new”. The name already occurs in the biblical prophet Ezekiel , where it denotes another place. For more information and to choose the name, see below .

The name "Tel Aviv" is often used as a placeholder for Jerusalem in political science literature and reports from international organizations . This is to express the view that Jerusalem is not the capital of Israel, or to avoid that the controversy over the capital question distracts from the real concern of publication.

The former official Arabic name of Tel Aviv-Jaffa is Arabic تل أبيب يافا Tall Abīb Yāfā . Officially, it is only used in a few areas today, such as traffic signs. The downgrading of Arabic to a minority language is related to the demand of a democratic majority in the country to anchor the Jewish nature of Israel more firmly in the state. Official bilingualism has long been considered an important expression of the democratic and secular state system, especially externally, but it was also a domestic political demand, for example by Vladimir Zeev Jabotinsky , a right-wing pioneer.

Importance of the city

In 2018, the city had 451,523 inhabitants, making it the second largest city in Israel after the capital Jerusalem. Greater Tel Aviv called Gush Dan covers a densely populated area with the neighboring cities of Ramat Gan , Giw'atajim , Cholon , Bat Jam and Bnei Brak , which are up to 14 km from the Mediterranean coast, and is around 3.8 million Inhabitants of the largest metropolitan area in the country. After the establishment of the state of Israel , most countries set up their embassies in Tel Aviv, as the status of Jerusalem was considered unclear according to the partition decisions of the UN .

After Israel 1980 East Jerusalem annexed and the Jerusalem Law , the "complete and united Jerusalem" had declared the capital of Israel, who urged the UN Security Council in its Resolution 478 on all states which had their embassies in Jerusalem, in addition to withdrawing them. That is why today almost all diplomatic missions are in and around Tel Aviv. The Tel Aviv Stock Exchange , the country's most important stock exchange, and the Israeli intelligence service Mossad are also headquartered here.

history

History of Jaffa

Archaeological excavations show that the coastal plain in the Yarkon estuary was roamed by hunters and gatherers of the Natufian culture as early as 9000 BC . They settled down and developed archetypes of agriculture. According to excavation findings, settlement continuity has existed since the Middle Bronze Age . Jaffa is mentioned on Egyptian inscriptions around 2000 BCE under the name Ipu , was by troops of Pharaoh Thutmose III. conquered, then formed the dominion of Pu-Baʿlu and was inhabited from around the 12th century BC by the so-called sea peoples, the Philistines and Canaanites , while the Israelites mainly settled inland. It is believed that it was a place of worship for the deity Derketo . In ancient times the port was mostly in the hands of the Phoenicians , whose deliveries of cedar wood for the construction of the first and second Jerusalem temples were transported to Jerusalem via Jaffa . From 587–539 BCE, Jaffa was under the control of the Babylonians , from 539–332 BCE under that of the Persians , and from 332–142 BCE under that of Hellenism .

In the Bible , Joppa is mentioned as the port of the Tarshish ships in the Book of Jonah ; likewise in the meeting of the Jewish Christian and apostle Peter with the Roman officer Cornelius (Acts 10). In Joppa the apostle Peter awoke the Tabita and lived for some time in the house of Simon the tanner ( Acts 9, 36-43). The Greek mythology locates the fate of Andromeda in Jaffa.

The Maccabees or Hasmoneans conquered the place during their revolt in the years 167–161 BCE. The Romans then took the place. With the suppression of the Zealot uprising of 66-70, Jaffa was destroyed under Titus Flavius Vespasian . From 132-135 the area was shaken by the Jewish Bar Kochba uprising against the Romans. Jaffa was under the Roman procurator of the province of Judea . Under Constantine the Great , the city became a bishopric. The rule of the Roman Empire ended around the year 330 and was replaced by Byzantium , who ruled Palestine until 636. This Greco-Roman phase was generally characterized by cultural syncretism that affected the Jews and the, in some cases, heavily Aramaic and polytheistic Arabs . The Arab Callinikos of Petra even became a teacher of rhetoric in Athens. Ancient authors often only used the term Arab generically for nomads . The emerging Christian communities belonged predominantly to the Monophysite tendencies , which is why the Byzantine state church regarded them as heretics .

In the year 622, with the Hijra of Muhammad, the Islamic calendar began and with it the spread of Islam , soon also in the southern Levant , as a result, Arabic was soon largely synonymous with Islamic from the outside world . In 636, after the battle of Yarmuk , warriors of the caliph ʿUmar ibn al-Chattāb conquered the place. The area was under the control of the Umayyads from 661 to 750, followed by the Abbasids from 750 to 972 , and the Fatimids from 972 to 1071 . The Turkic-speaking Seljuks defeated them in 1071 and also made Jaffa their own.

In 1099, Godfrey of Bouillon took the city as part of the First Crusade . In the Middle Ages, Jaffa was very important both militarily and for trade. For the Crusaders, Jaffa was of particular strategic value as the closest natural port to Jerusalem. Not far from Jaffa in the north was the fortress of Arsuf . Jaffa was fortified by Godfrey of Bouillon with the help of the Venetians in 1100 and formed the center of a county. Venice received a quarter of all newly conquered cities in exchange for military service. In 1102 an Egyptian army of almost 20,000 men moved to the gates of Jaffa, but had to withdraw again without a siege. Dagobert of Pisa , the first Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem , had unsuccessfully claimed the city for himself. When the Count of Jaffa Hugo II von Le Puiset rebelled against King Fulk in 1134 , the county was divided into a number of smaller units, Jaffa itself became a crown property.

In 1187, after the defeat of the Crusaders in the Battle of Hattin , near the Sea of Galilee , the Ayyubid Sultan Saladin conquered Jaffa. On September 10, 1191, the army of the Third Crusade under Richard the Lionheart occupied the ruins of the city without a fight, after it had been razed on Saladin's orders before the battle of Arsuf in the autumn of 1190. At the end of July and August 1192, Saladin took advantage of a departure from Richard and some of his followers to Acre to seize the city in the siege and battle of Jaffa , but was ultimately repulsed. On September 3, 1192, Saladin assured the Crusaders possession of Jaffa in an armistice agreement. As part of the Fifth Crusade , the Peace of Jaffa between Emperor Frederick II and Sultan al-Kamil was concluded here in 1229 , after which the Christians, among other things, got Jerusalem back without a fight.

In the Kingdom of Jerusalem , the heir to the throne usually bore the title " Count of Jaffa and Askalon ". Henry of Champagne left Jaffa to his daughters. After the death of Alice of Champagne , Jaffa fell to her daughter Maria of Champagne, who was married to Walter IV of Brienne . After Walter's death in 1246, Jaffa fell to Mary's brother, King Henry I of Lusignan . Between 1246 and 1247 enfeoffed Henry I. John of Ibelin with Jaffa. In 1260 the Mamluks advancing north from Egypt under Sultan Baibars I conquered the city in a half-day siege, ended the rule of the Crusaders and overcame the foreign rule of the Franks , which the Muslims, and also many Christians who did not practice according to the Roman rite , experienced as a traumatic foreign rule or Latins . One reason for the almost exclusively military character of their presence was their very high child mortality .

The title of Baron of Jaffa was carried on by nobles in the Kingdom of Cyprus after the city was evacuated . In addition to new crops, crusaders also brought carrier pigeon breeding to Europe. Similar to al-Andaluz , times of war were followed by times of relative calm, which allowed the Franks to gain knowledge of Arabic medicine . The crusaders also hoped for help in an emergency from an alliance with the Mongolian Golden Horde that Philippe de Toucy had sought. The Mamluks left Jaffa largely destroyed and depopulated.

In 1516 the city fell to the Ottoman Empire and was able to regain its old economic importance. The increasing demand for grain in the Italian states, as a result of Sweden's entry into the war in the Thirty Years' War , made Jaffa a destination for English, Dutch and Hanseatic merchant ships from the 1610s . Cotton also increasingly became an important commodity . With the surrender of the Ottoman Empire in 1535, French, Venetian and Genoese trading establishments were given generous tax privileges by the Ottomans and were given internal autonomy. Administrators and consuls conducted the internal affairs of the offices assigned to the foreign traders.

Increasingly, Jaffa was also a pilgrimage port on the way to Jerusalem and to other Loca Sancta , which remind Christians of the earthly life of Jesus , and which have been accessible for pilgrimages since the 4th century . The costly but safe sea voyage on Venetian galleys lasted 30 to 40 days. For example, the Benedictine monk Dom Loupvent (approx. 1490–1550) from Lorraine made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1531: For the outward journey (June 22nd – August 4th) and the return journey (August 27th – November 20th) with all stays, as well as the way from Jaffa to Jerusalem and back (August 4-27) took him 245 days. Stops on his journey were Venice, Rovinj (Rovigno), Otrante , Iraklio (Candie) on the Venetian possession of Crete , Limassol on the also Venetian Cyprus , Jaffa, Jerusalem, then again Jaffa, a place called Salins on the south coast of Cyprus, then a stopover in a bay on the south coast of the Peloponnese , the Greek islands of Zakynthos (Zante) and Corfu , Rovinj and finally Venice again. Amazed, he reported about the common prayers of Christians and Muslims at the tomb of Lazarus .

The Christian and Jewish populations had the legal status of dhimmi as holders of divine revelations and “people of the scriptures”, who admittedly were accused of falsifying the scriptures (Arabic: Tahrīf ) , but they also paid the jizya poll tax , but were also entitled to them to protection from arbitrariness, extensive occupational freedom and freedom to practice one's religion. Around 1665, the appearance of the alleged messiah Shabbtai Zvi and his " prophet " Nathan of Gaza caused a stir in the Jewish community. The Jewish hope from Smyrna moved freely in the eastern Mediterranean, because the Ottomans offered their subjects freedom of movement.

In 1775, Jaffa was besieged and captured by Mamluks under Muhammad Bey Abu Dahab, and he massacred the entire population. Coming from Gaza , which his troops had taken on February 25th, 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte besieged Jaffa during his Egyptian expedition from March 4th to 7th, 1799. The French officer who was to lead the negotiations about a non-fighting surrender of the city was Ottoman fighters had their heads cut off and shown to the French from the city wall, impaled on a stake. This was followed by a six-hour artillery bombardment of the city and, after the capture, the looting and execution of Commander Abu-Saab and nearly 3,000 prisoners. The bloodbath was justified by the lack of water and food for prisoners of war. At the same time, the plague had broken out in Jaffa and there were numerous cases of sexual violence against women. Napoleon then gave his military doctor René-Nicolas Dufriche Desgenettes the order to poison the sick French soldiers. Favored by poor hygienic conditions, plague and cholera returned repeatedly in the decades that followed. In 1806 the traveler François-René de Chateaubriand lamented the miserable state of the city in Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem .

Modern armed Egyptian troops of Muhammad Ali Pasha moved into Jaffa to conquer Syria and south-east Anatolia in 1832, which, however, was ruled again by the Ottoman Empire from 1841 after the military intervention of the major European powers in 1839. Muhammad Ali received the Ottoman recognition of his dynasty over Egypt and Sudan. Little Jaffa was thus subject to the Sanjak of Jerusalem, on whose northern border it was. This sanjak, in turn, was part of the Damascus province. From 1840 on, the reform of the economic system called Tanzimat gave the building industry a boost in development. After 1841, with the pacification of the area and the end of the fighting, soldiers of Ibrahim Pasha's armed forces and their families were resettled in Palestine. The majority of these were Egyptian farmers and Fellachians , but there were also Maghrebians , Circassians and Bosniaks among them . In addition, the Arab slave trade , which also ran on the Jeddah - Tabuk - Amman route , brought a smaller number of people from central and eastern Africa to Jaffa.

About 200 Jews lived in Jaffa around 1840. From the 1820s onwards, the Ottomans favored the settlement of Maghrebian Jews, as they saw in them a counterweight to the rebellious Arabs and hoped for good tax returns from them. Jews and Christians often paid substantial taxes and duties for so-called property rights, which included the possibility for Jews to pray at the Kotel in Jerusalem. Since the post of governor or tax leaseholder ( mültezim ) of the Sublime Porte could be bought, incumbents tried to take in as much as possible in order to make their purchase of office appear profitable. Therefore, after the Crimean War, more and more Christian subjects of the Russian Empire pushed into Palestine and tried to dispute France 's status as the protective power of Arab Christians . Russia made such claims since 1774 at the latest. They also settled near Jaffa. In addition, there were other foreigners and locals who enjoyed consular protection . After the Young Turk genocide of the Armenians , an Armenian Orthodox community was later formed in Jaffa.

From the 1860s there were scheduled steamboat connections from Marseille and Trieste that brought pilgrims and tourists into the country. The Park Hotel of the von Ustinov family was established in 1884 . On March 31, 1890, a French company began building the Jaffa – Jerusalem railway , which went into operation on September 26, 1892. The elite was subject to a westernization , which was also influenced by French, British and American clinics, mission schools and universities. These were mostly in the Arab metropolises of Beirut , Damascus and Cairo , where wealthy families from Jaffa often spent most of the year. Further studies then took her sons to Europe. The al-Taji al-Faruqi family from Jaffa owned 50,000 dunams of land at the end of the 19th century . The land ownership of wealthy families had been rounded off with the Ottoman legislation from 1858 , as farmers had unwittingly recorded their land rights in order to avoid taxation. Some of the aristocrats , who were often heavily in debt , were now selling land they had already leased to the new immigrants. For this reason, too, in the Ottoman Empire, which was marked by economic collapse, many peasants were forced to flee the countryside and wage labor in the cities, which, however, was withheld from them by the increasingly socialist-minded Zionists, as they did not want to "exploit" Arab wage laborers, but rather to rebuild a purely Jewish economy.

The policy of the Jewish pioneers followed the principle of “Jewish work”, which was also known as self-reliance . The Jews should receive a normal social structure of “peasants and workers”. The other part of the same conception of society was "Jewish self-defense". Both of these gave rise to the accusation that Zionism was an imperialist plot and that the Jews were segregating to the detriment of the Arab population. Unlike the elite, many uprooted peasants sought support from traditional Islamic values. The movement of the “ Islamic Awakening ” emerged from its lower middle class , and newspapers such as Filastin , which was printed in Jaffa from 1911 onwards , provided impulses for growing Arab national consciousness . The frequent reference to the old traumas of the Crusades served as a means of political mobilization.

During the First World War, the Ottoman administration of Palestine forced the Jews living in Jaffa to leave the city because they were considered hostile citizens because of their Romanian or Russian origins. On November 16, 1917, Jaffa surrendered to the superiority of British troops under the command of Edmund Allenby , which ended the Ottoman rule in the following year. The expelled Jewish population had previously returned to the city through the mediation of the German Empire , which was allied with the Turks . In 1915 the British had promised Arab politicians an area from Adana (now Turkey ) to Aqaba (now Jordan ), including Jaffa. In May 1916, Jaffa was in the area that, according to the plans of the Triple Entente, should have been under joint British, French and Russian protectorate . Meanwhile, Arab promises were not fulfilled either, because the extensive desertion of Arab soldiers from Ottoman units did not materialize.

After the end of the First World War on the Palestine front, Islamic-Christian committees were formed which, from January 27 to February 9, 1919 , drafted a program against the settlement of Jews in "southern Syria" at the pan - Arab All - Syrian Congress in Jerusalem. However, among the Arab activists, who were in complete agreement with one another in their rejection of Zionism, there was disagreement about the desired alternatives, while Muslims were in favor of Palestine as an "inseparable part of Syria", while Greek Orthodox residents of Jaffa also agreed with British Protectorate; Catholic Arabs advocated a French protectorate. In addition, the Arab population was divided into supporters of the old political dynasties of the Husseini and Nashashibi. Pan-Arabism , Lebanonism and Greater Syrianism also competed among the elites across the region . There was no homogeneous Arabism or even a unified and political Arab-Palestinian identity.

In 1920 tensions erupted as a result of the political developments in Syria and because of the division of mandate areas at the Sanremo Conference . The secret Sykes-Picot Agreement of May 1916 - a British-French balance of interests - was implemented contrary to promises to the contrary and against the will of the majority population. Initially peaceful protests quickly turned into rioting. In May 1921 they peaked in the Jaffa suburb of Neve Shalom. To defuse the situation, the divide and rule ruling British mandate power banned several immigration ships from landing in Palestine.

According to the 1931 census, the Jaffa Territory had 30,877 inhabitants, around 70% of whom were Muslim. At this point the Arab population was already heavily proletarianized and repeatedly vented their frustration with strikes . After fighting with the British police, in which a policeman and 22 demonstrators died in Jaffa in October 1933 and the politician Musa Kazim al-Husaini was seriously injured, to which he later succumbed, the movement radicalized. Isolated neo-Salafi groups formed among Jaffa's Muslims , and Izz ad-Din al-Qassam was soon considered to be their most influential spokesman in Palestine. His short-lived organization Black Hand , however, broke due to the crackdown on the part of the British and their minimal mobilization power. As part of the “Operation Anker” carried out by the British Mandate Government to combat the Great Arab Uprising , large parts of Jaffa's old town were destroyed in 1936. Passers-by were shot at from the minaret of the Hassan Bek Mosque . The plan of the Peel Commission , which provided that Jaffa would continue to be part of a British zone, while Tel Aviv was to be added to a zone under Jewish administration, should remedy this . On August 26, 1938, twenty-four visitors to an Arab market in Jaffa were killed by a bomb in a sequence of violence and counter-violence. The British, tired of both Arab and Jewish demands, published the White Paper in 1939, putting an end to their policy of kindly tolerating Jewish immigration. These statements by the British government were an affront to the Zionists. David Ben-Gurion , who was recruiting Jewish volunteers for the British , announced at a Zionist congress in New York in 1942 : “We are waging war on England's side as if there were no White Paper, and we fight the White Paper as if there was no war. "

In 1938 the modern port of Tel Aviv opened , which meant the loss of their jobs for many workers in the port of Jaffa. Jaffa had previously found it difficult to hold its own against the competition from the pilgrim ports of Alexandria and Beirut . In 1945 Jaffa had 101,580 inhabitants, of whom 53,930 were Muslim , 30,820 Jewish and 16,800 Christian . While neighboring Tel Aviv, with a Jewish majority , was added to the Jewish state in the UN partition plan , Jaffa was originally intended as an enclave of the Arab state. As early as the day after the UN resolution of November 29, 1947 and before the outbreak of the violent conflict, the majority of Jaffa's Arab elite - officials, doctors, lawyers, business people and their families - went into exile, often with people living in nearby countries Relatives.

On May 14, 1948, Jaffa was taken by militias of the Hagana and Irgun during the Palestinian War ; the British had since retreated. Reports of a massacre in the village of Deir Yasin , near Jerusalem, and targeted but partly false rumors about further attacks on the Arab civilian population, as well as threats, triggered a second, now significantly larger wave of refugees, with the Arab residents of Jaffa mainly on the And were resettled in the Gaza Strip , particularly in the al-Shati camp. Many expected to return to their homes soon. As a result of these events, which the Palestinians referred to as Nakba , the flight or expulsion of a large part of the Arab population, their population in the city decreased by around 65,000 to just under 5,000 and was around 20,000 in 2017. The term nakba is rejected by the majority of the Israeli population, the subject is largely a taboo .

The so-called Old Jaffa is now mainly used for tourism and is home to numerous souvenir shops and private galleries. The consumption-oriented upgrading of Jaffa to a tourist attraction only took place in the 1990s, whereby a significant part of the historical building fabric was removed. This procedure was justified in part with the archaeological excavations carried out. The subsequent directly to the Old Town district of Ajami previously considered "problem area" and drug transshipment point, a subject that in the film Ajami of Scandar Copti is treated. Since then, part of Jaffa has been converted into a connected nightlife area for wealthy nightlife visitors . To this day, there are also institutions and churches of Arab Christians in Jaffa , as well as embassies, including the French. Jaffa, like other parts of the city, is subject to gentrification .

History of Tel Aviv

The first places in the area of today's Tel Aviv emerged in the south near Jaffa: From 1881 Yemeni Jews built the agricultural hamlet Kerem HaTeimanim (German vineyard of the Yemenis ) here. Yemenis also devoted themselves to their traditional craft as silversmiths, in 1900 they made up around 10% of the Jewish population of Palestine. Even before this first Jewish immigration, around 20,000 Jews from the Old Yishuv lived in Palestine. In 1887 the Sephardi Aharon Chelouche , Chaim Amzalak and Joseph Moyal founded a settlement outside the city gates with the ambitious name of Neve Tsedek (English: Oasis of Justice ), based on a verse in the Book of Jeremiah . Neve Shalom was created in 1890. In 1904 Abraham Isaak Kook became chief rabbi of the Ashkenazi community. He created the ideological basis for the later religious Zionism of Gush Emunim , at that time still the view of a small minority, whose dissolution some expected. As early as 1871, Pietist Württemberg Protestants , the Templars , were working in the hamlet of Sarona (1947 in Tel Aviv) to develop modern agriculture in Palestine. In Jaffa's suburbs, Valhalla and the American-German Settlement in the immediate vicinity of Tel Aviv (1948 with Jaffa to Tel Aviv), Templars pushed the commercial and industrial modernization of Palestine forward.

Tel Aviv's real history began in 1909 with the land society Achusat Bajit ( Hebrew אחזת בית Achusat Bajit ). The family of the later Prime Minister Moshe Scharett also belonged to the founding families . Achusat Bajit later merged with two other new neighborhoods - Nachalat Binjamin and Geʾula. The new district was named "Tel Aviv" after the title of the Hebrew translation of the utopian novel Altneuland by Theodor Herzl made by Nachum Sokolow after a general meeting of Achusat Bajit's residents decided on the new name on May 21, 1910. Among the proposals were: New Jaffa - Jefefija ("The Most Beautiful") - Neweh Jafo ("Aue Jaffas") - ʾAvivah ("The Spring One ") - ʿIvrija ("The Hebrew") and finally Tel Aviv ("Spring Hill "). Tel Aviv prevailed. In Sokolov's poetic translation, Tel (ancient settlement hill) stands for "old" and Aviv (spring) for "new". Tel Aviv soon became the refuge for many long-established Jaffa Jews.

Sokolow took the name from the book of Ezekiel , in which the name designates a place on the river Kebar in Babylonia , where the prophet receives his revelations : "This is how I came to the abducted people who lived in Tel-Aviv" ( Ez 3:15 a EU ). These revelations say, among other things, that "one day all the scattered people of Israel will be returned to Eretz Israel ". The underlying motivation of the Zionists, however, was primarily political and hardly religious. This Zionism, which was oriented towards the founding of the Jewish state, formed the main direction of the movement, but competed e.g. B. with national-cultural Zionism, which made demands on life in the diaspora . As an alternative to Zionism, the Algemeyner Yidisher Arbeter-Bund arose in Lite, Poyln un Rusland (Bundisten) . The Alliance Israélite Universelle , which was also active in Jaffa from 1870, offered Sephardic Jews an identity mainly focused on France; even Italian imperialism tried to bind Sephardic Jews to Italy , for example in the Dodecanese . Political Zionism took a different direction: At the 7th Zionist Congress in 1905 in Basel , the final decision was made in favor of the Zionist conquest of Palestine; a Jewish settlement colony in Uganda proposed in 1903 had been rejected.

On April 11, 1909, the plots in Achusat-Bajit, which had been parceled out beforehand, were raffled by en: Akiva Aryeh Weiss in the presence of the founders of the district, who had acquired shares in the Achusat Bajit company, and their families: collected on 60 on the same morning on the beach He wrote the names of the members of the society in black ink and the parcel numbers on another 60 mussels. During the lottery procedure , a boy and a girl each drew a shell with a number or name at the same time, so it was decided who was given which property. This day is considered the founding day of Tel Aviv. The first urban complexes based on plans by Boris Schatz , initially emerged in an eclectic style based on Art Nouveau , which is why architecture critics soon referred to Tel Aviv as a provincial "Little Odessa ". Around 200,000 Jews lived in this pogrom- shaken metropolis on the Black Sea , many of them in dire poverty , which increased their will to emigrate. Theodor Herzl's book The Jewish State often met with their approval. In the Holy Land, the Jews should finally be farmers again, so the demand, and some newcomers were accordingly critical of this urban lifestyle. Jaffa gained international fame during this time with the export of the Jaffa orange . Between 1880 and 1914, the focus of Jewish agricultural settlement was to the south and south-east of Jaffa, and another focus was in northern Palestine, west of the Sea of Galilee. On November 2, 1917, the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Arthur James Balfour , made a vague promise for the first time in favor of "the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine" . The Balfour Declaration asserted that "civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities" must not be affected.

The coat of arms and the flag of the city contain two words from the biblical book of Jeremiah under the red Star of David : "I (God) will build you up, and you shall be built" (Jer 31: 4)

On May 11, 1921, the connection with Jaffa was loosened, and Tel Aviv received its own municipal administration as a semi-autonomous township within Jaffa through the High Commissioner Sir Herbert Samuel . This was the British reaction to the unrest in Jaffa of 1921. In June 1923, the Mandate Government determined which districts of Jaffa belonged to Tel Aviv Township, in addition to Tel Aviv proper, Jaffa's older north-eastern suburbs with predominantly Jewish residents, such as Neve Tsedek (1887 founded), Neve Shalom (1897), Machaneh Jehudah (1896), Jefeh Nof (1897), Achawah (1899), Battej Feingold (1904), Battej Warschah, Battej Schmerling, Battej Joseph (1904), Kerem HaTeimanim (1905) and Ohel Moscheh (1906). In the spring of 1923, Tel Aviv's first power station went into operation, soon ending the age of kerosene lamps and generators. The leading entrepreneur was Pinchas Ruthenberg , founder of the Anglo-Palestine Electricity Company . Much to the displeasure of the left-wing Zionist pioneers, whose ideal was nothing less than the “New Jew”, Jewish immigration from 1925 onwards consisted of bourgeois and “capitalist” former small and micro-entrepreneurs with a growing proportion . There were internal Jewish labor struggles , often with the solidarity of Arab workers. The Histadrut promoted the emergence of Arab trade unions. Around 25,000 Jews left Palestine after a short time in the wake of the global economic crisis and headed for European colonies overseas; most of them were completely alien to the Zionist ideology.

In the dispute over the enforcement of even the observance of Yom Kippur religious parent Shabbat rest in the extended Tel Aviv, threatened the representatives Neve Tsedeks and Neve Shalom in 1923 in case the future common Township would not commit to the Shabbat currency, the reincorporation of their neighborhood to aspire to Jaffa. So those responsible for the whole of Tel Aviv agreed to officially stand up for the keeping of the Sabbath, but without the claim to be able to determine its observance in private. The Ashkenazi Great Synagogue was completed in 1926, followed by the construction of the Sephardic Great Synagogue Stiftszelt from 1925 to 1931 . Numerous smaller minjanim and prayer rooms were built in the districts.

On January 20, 1924, the residents of the expanded Tel Aviv elected their township council for the first time, which appointed Meir Dizengoff as mayor from among them on the 31st of the month . In July 1926, the Tel Aviv Homeowners' Association filed a declaratory action before the Palestinian Higher Court in Jerusalem to determine who was entitled to elect the Township Council in Tel Aviv, as the statutes were not clear about this. The High Court made a ruling that only taxpayers would be eligible to vote, excluding many previously eligible voters from future elections. In December 1926, the city of Jaffa excluded the residents of Tel Aviv from taking part in the city council elections, but after protests the Tel Avivis were able to re-elect their representatives on May 27, 1927, the seats went to Dizengoff and Chaim Mutro.

The city commissioned the Scot Patrick Geddes to develop a master plan for Tel Aviv, which he did in 1927–1929. Tel Aviv was to be designed as a garden city with mostly free-standing buildings according to the principles of hygiene and modern urban planning . The city should be by the sea, because it should - comparable to New York and Buenos Aires - become the gateway to a new home. And the city, which Theodor Herzl imagined to be visually similar to Vienna , should have healthy sea air, because the Zionists saw how in the consumption- plagued Central European metropolises thousands of Jews lived in stuffy aisle kitchens. The Geddes Plan was only partially implemented , however, as private investors often obeyed their own financial interests, which exposed them to severe public criticism. Therefore only half of the 60 planned parks could actually be created. From 1927, the densely built-up workers and industrial district of Florentin was built for Jews from Thessaloniki . The Shapira neighborhood to the east was built by Uzbek immigrants. Thus was formed a prosperity gap between the of left ideals or from the Haskalah influenced members of the elite residential districts in the north and the economically weaker Mizrahi south of the city who felt socially disadvantaged and usually were, barely as it capital and western education possessed. They were often met with suspicion and had to prove their Jewish-Israeli identity . This problem intensified especially after the founding of the state, with the strong influx of culturally Arabized Jews .

Full independence from Jaffa Tel Aviv received on 12 May 1934 but that the self-designation since March 1921 'Ir used (city) than the Palestinian according to municipal code ( English Municipal Corporations Ordinance , = local authority regulation ' was raised) for the independent city. With the rise of National Socialism in Germany, the need for housing grew; therefore, contrary to the original intention, construction now had to be carried out quickly, functionally and inexpensively, by architects such as Richard Kauffmann , Wilhelm Haller , Erich Mendelsohn , Lotte Cohn , Leo Adler , Arieh Sharon , Genia Awerbuch , Dov Karmi , or Yehuda Magidovitch , all of them architects who felt committed to the principles of the Bauhaus and the International Style . With Zeev Rechter , a student of the Berlin architect Erich Mendelsohn also came to Tel Aviv; Shmuel Barkai had studied at the international style-building Le Corbusier in Paris. However, they made numerous functional concessions to the conditions of the Levant and adapted their plans accordingly, because the climate of Palestine was already rich in contrasts: "Brutal hot days are followed by frosty nights, wild downpours are followed by cloudless drought, and icy northern storms are followed by scorching south winds" , Egon Friedell described it in 1936. The architects also created the modernist designs for the pavilions of the Levante Fair in what is now the Old North . The Weißenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart, insulted by the Nazis as "Jewish-Bolshevik", also served as a model .

The Haʿavara Agreement made it possible for refugees from Germany to import German building materials and other goods, such as machines that seemed useful for a new beginning, to Palestine, which they paid for with their assets in Germany. From December 1931 , the Reichsfluchtsteuer imposed taxes on direct cross-border financial transactions, the rates of which were repeatedly raised by the Nazis in order to deter holders of assets in Germany, regardless of religion or nationality, from exporting their bank balances through high taxation, or to withhold these balances for tax purposes , as a result of which refugees had to leave penniless. Among the new olim were many members of the assimilated educated middle class , for which there is not always a suitable work, also-stretched the Jeckes as German and Austrians were called mockingly, with its formality on. The word got around that one had to go to construction sites with “Here you go, Doctor! - Thank you, Doctor! ” Bricks handed. The jackets didn't want to part with their jacket in the heat either. They lived in the social canton of Ivrit ("no tone Ivrit "). This led some Zionist politicians to encourage the immigration of more easily integrated immigrants from Poland. On June 16, 1933, the Berlin-trained economist and left-wing Zionist Chaim Arlosoroff was found murdered on the beach in Tel Aviv.

The Arab population in nearby Jaffa not only remained unmolested by any displacement, but continued to grow, but the German immigrants brought in their intellectual baggage, in addition to the promise attributed to Israel Zangwill “A land without a people for a people without a land”, also other views with who did not even show interest in their new Arab neighbors. In his book Kulturgeschichte in 1935 , Alfred Weber classified Islam as a “secondary culture of the second level” , and the Islamic scholar and Prussian minister of culture, Carl Heinrich Becker, specified: “[Islam] is nothing other than living on, but always persists more Asiatic Hellenism . ” From 1925 to 1933 the Brit Schalom group nevertheless undertook isolated initiatives for an understanding with the Arab population . To deal with the Arabs became the task of selected Arab Jews and Mista'aravim and remained a purely secret service activity. The majority consciously suppressed this part of reality.

From February 1939, the Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration promoted the emigration of around 30,000 Jews. 66,848 people fled Austria in this way by October 1941. The 5th Aliyah brought a total of 197,235 refugees into the country. In July 1941, non-Jewish Palestinian Germans living in the Sarona district were disembarked for internment in Australia. Your German school in Sarona initially became the quarters of the Notrim Jewish auxiliary police . The city police also dealt with Jewish delinquents who, to the great satisfaction of the future Israeli national poet Chaim Nachman Bialik, had been around for a long time. When a certain Renzel, the first thief arrested in Tel Aviv, was caught in the 1920s, he said: “We will only be a normal people when there are finally Jewish police officers, Jewish prostitutes and Jewish bandits on our streets . "

In 1939, 90% of the Jewish population lived in the cities, because the area comprising around 20% of the agricultural land at the beginning of the 1940s, which the Jewish National Fund in particular had bought from Arab latifundia owners, could no longer accept people. However, rural life in the kibbutz and moshav determined the image that Zionism spread of itself. In contrast to neighboring Jaffa, Tel Aviv was from the beginning a Jewish settlement with a corresponding majority of the population. According to the UN partition plan for Palestine , Tel Aviv was therefore intended as part of the Jewish state. The city grew rapidly because, along with Haifa , it became the most important port of arrival for Jewish immigrants to Palestine. In 1926 Tel Aviv had 40,000 inhabitants, in 1936 there were already 150,000 inhabitants.

During the Second World War , Tel Aviv was bombed by Italian planes on September 9, 1940, serious damage was caused and over 200 people lost their lives. Another air raid followed in June 1941. The fear that Axis troops would advance through North Africa to Palestine spread in the Yishuv when Italian and German units were just outside the gates of Cairo in 1942 and King Faruk I , who was inclined to Italian fascism , spread . had spoken out in favor of the neutrality of his country, which is why part of the Zionist leadership was evacuated to Great Britain. Tel Aviv became the point of contact for Allied troops on transit or on vacation, including New Zealanders and Australians, as well as for Polish armed forces of the Soviet Union , which a Polish cemetery in Jaffa still reminds us of today. Members of the Army of Free France and Greek armed forces also waited here to be deployed. At El-Alamein , these British-commanded units were able to stop the German advance. Despite the fact that the armed Jewish movements Haganah and Irgun had ostensibly remained silent towards the British mandate troops, the Lechi group, which initially had 200 to 400 members , launched attacks against their security organs, as the British were pursuing a restrictive immigration policy even after the first reports about the Holocaust became known detained for Jews to Palestine. Members of the Lechi planted a bomb that killed three police officers in Tel Aviv on January 20, 1942. On November 6, 1944, the British Colonial Minister Lord Moyne died in an assassination attempt by the Lechi in Cairo.

The British, who prevented ships such as the Struma or Exodus from landing in Palestine and justified this with the protection of the interests of the local Arab population, feared “another Ireland ” and the drifting of the Arabs into the camp of the Axis powers. Confirmed news about mass murders of Jews in Europe led to large demonstrations in Tel Aviv. However, the British only allowed the Youth Aliyah . The rest of the Jewish immigration was mostly illegal until the end of the mandate, 50,000 passengers of intercepted ships were interned in Cyprus . In 1947, before the outbreak of the Palestinian War , Tel Aviv already had 230,000 inhabitants.

Survivors of the National Socialist genocide , the displaced persons , were able to travel to Eretz Israel after the end of the British mandate, often after staying in German DP camps for several years , but the fate of the survivors, who were often physically and mentally broken, only played a very small part public discourse in the new state, rather the ideal of the defensive, capable and optimistic pioneer or Tzabar dominated . Even David Ben-Gurion , Mapai politician and executive head of the Jewish Agency for Palestine , was critical of the survivors' ability to integrate into the country. In keeping with the prevailing attitude in the Yishuv , the head of the German Templar Society and Nazi propagandist Gotthilf Wagner was tracked down and killed in Tel Aviv on March 22, 1946 . The act was one of the first so-called Targeted killings in Israel. In June 1948 there was an outbreak of violence between Jewish associations during the unloading of arms deliveries from the freighter Altalena , which was sunk off Tel Aviv. France had delivered weapons to the value of 153 million francs on the ship and thus secured political influence and further export deals. The USA and the USSR were also among the first supporters of the newly emerging state of Israel.

After independence

The State of Israel was established with the Israeli Declaration of Independence , passed on May 14, 1948 in Independence Hall on Rothschild Boulevard . The Egyptian Air Force bombed Tel Aviv. Between 1948 and 1951, Yemeni, Iraqi and Egyptian Jews came to Israel in large numbers. On April 24, 1950, Jaffa was administratively connected to the former suburb of Tel Aviv, which is also known as annexation . The name of the united city was initially Tel Aviv . On August 19, 1950, it was renamed Tel Aviv-Jafo to get the historical name Jaffa . With funds from the controversial Luxembourg Agreement - the so-called reparation agreement with the Federal Republic of Germany - the infrastructure was further expanded from 1952.

The years 1955–1957 and 1961–1964 brought renewed waves of immigration from Arabic-speaking countries . The official introduction of the Semitic language Ivrit , communicated in the Ulpan , and the displacement of Yiddish from urban life, facilitated their linguistic integration. The school career of children from Mizrachim families was, however, often rocky. The Jewish Swiss writer Salcia Landmann believed she had to report in 1967: "Teachers and educators in Israel generally complain about the sometimes weak talent and the low eagerness to learn of the children of immigrants from Arab countries." About this paternalism, which is openly displayed, the majority It also belonged to the left-wing Ashkenazi elite that they, as Salcia Landmann does in the supplement to this quote, generally advocated “mixed marriages” between the Ashkenazim and the politically mostly right-wing Sephardic Mizrahim. However, in 1967 there were only 15% mixed marriages in Israel for the time being.

Yiddish was considered the " jargon of the cowardly Diaspora Jews ", and family names were Hebrew to break with the past. It was not until the politically backed Eichmann trial in Jerusalem that the diaspora was reassessed in the 1960s. When it was broadcast on the radio, the survivors were really listened to for the first time. David Ben-Gurion, who had initiated the process, initially only tried to include the Holocaust in the continuity of anti-Semitic pogroms . Under the governments of Golda Meir and Menachem Begin , however, the crime of humanity was subsequently reinterpreted as the central cornerstone of Israel's right to exist . In the 1970s, a new interest in the culture of the diaspora arose, which for example founded the success of the singer Chava Alberstein . The Jewish-Spanish Ladino was also revived in Tel Aviv. In 1984 an exhibition in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art brought the re-evaluation of the architectural heritage and the previously unknown name White City ; various authors have argued that this urban planning is based on identity-political motives.

The city became the center of urban life in Israel and continued to grow: After a settlement area along the sea had been built up until 1936 with the immigration of Jews expelled from Germany - the so-called Jeckes - between 1950 and 1960 new districts were built in the east where there were later, mainly in 1984 and 1991, the often less affluent Ethiopian Jews settled, while from 1975 wealthier families moved to Ramat Aviv in the north and to the eastern and southern environs. In the process, buildings with a lot of exposed concrete that were less suitable for social cohesion were also created, for example in the style of brutalism . City districts built hastily and under pressure to save from mostly state-subsidized apartments - known as Shikunim - developed the problems of a metropolitan banlieue . The population pressure, which is often associated with stress , further densification and redensification and a growing number of high-rise buildings have again greatly changed the cityscape since the 1990s and with it the social structure , due to the associated gentrification . However, the dark-skinned Ethiopian Jews are hardly visible in the life of the inner city. For their part, they, who often feel excluded and discriminated against , keep their distance from the White City. In 2015, police attacks on Ethiopian Jews led to ongoing protests in Tel Aviv.

The conversion of Tel Aviv into a high-rise city began in 1962, when the trade union federation Histadrut had the architecturally valuable Herzlia-Gymnasium demolished to make way for the Schalom-Meir-Tower . The loss of this cultural heritage led to the city's first monument protection initiative . The Dizengoff Center was the first shopping center . In 2006 Tel Aviv-Jaffa had 385,000 inhabitants, in 2015 there were around 433,000 inhabitants. The Israeli state is making efforts to distribute the population in the country and cities such as Ashdod and Beersheba in the south of Israel are constantly being expanded. While school and military service lead to rapid adaptation in the children of new immigrants, the idealized ideas of Israel that their parents have about Israel usually cannot stand up to reality ; Israelis are often experienced by them as rough and indifferent. The attitude of those already living in the country is often ambivalent , as every new aliyah is offered better starting conditions. At the same time, there was always a slight emigration of Jews from Israel.

Through the consolidation of the political right, which was laid out in Israel from the beginning with liberal-conservatives like Chaim Weizmann or revisionism , which first took shape with the election of Menachem Begin in 1977 and determined the political discourse in the era of Benjamin Netanyahu , a noticeable one has emerged Alienation between Israel and the predominantly left and liberally oriented Jews in the western diaspora set. For example, the New Israel Fund supports projects that seek a balance with the Palestinians . Nevertheless, for them, as well as for economically liberal to neoconservative -minded Jews, mainly in the United States , Tel Aviv continues to be an important point of reference. The latter have repeatedly campaigned for the privatization of state and trade union companies of the Histadrut . Since these people usually only stay temporarily in Tel Aviv, this increases the leisure time orientation of the people in the city, whose working hours, especially in highly qualified areas, are often based on the office hours of San Francisco or Los Angeles . A well-known dictum therefore says "Jerusalem prays, Haifa works - and Tel Aviv celebrates". This hedonism is often blamed for the restless non-stop city of Tel Aviv in Israel and in the diaspora. The emotional affiliation with Israel, known as Ahavat Israel , is often also associated with criticism , and with the question of how and by whom this criticism may be expressed. For example, the so-called BDS campaign is accused of having unfair motives.

The very high cost of living, even by Israeli standards , and the increased social inequality caused by the dismantling of the welfare state led to the protests of 2011/2012 . The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel recently worsened the often precarious income situation . Tel Aviv, however, also officially cultivates its image as an international party metropolis with tolerance for homosexuals and the Tel Aviv Pride event . The organization Agudah for Gays, Lesbians, Bisexuals, and Transgender in Israel represents her interests . Today, many non-Jewish labor immigrants from Eastern Europe and from South and East Asia also live in the city. In addition, post-Soviet immigration in particular brought many people into the country who, according to the Halachian view, are not considered Jews, which regularly leads to debates on the question who is a Jew? leads. In 2019, around 300,000 people were affected in Israel. In the case of marriages that can only be carried out under the supervision of the Orthodox rabbinate , they are under pressure to legitimize themselves, which is why many prefer to marry abroad. Soviet Jews were 90.5% Russian-speaking in 1989 , which is still noticeable in everyday life today. The Russian government tries to maintain its solidarity.

Another group of the population are so-called New Jews , which include different groups of people who are newly recognized as Jews. The non-Jewish refugees living in Tel Aviv have mainly come from countries south of the Sahara since 1990 . 140,000 people were expelled in 2000, some of the refugees remain in the country. Your residence status is often uncertain. Many refugees hope to use Israel as a transit country . After the waves of immigration from the post-Soviet Aliyah largely subsided, French Jews in particular have recently settled in Tel Aviv-Jaffa because of the increasing threat of anti-Semitism in France . Israel offers them a kind of "security guarantee", many bought apartments in Tel Aviv-Jaffa as a precaution.

In Tel Aviv , Prime Minister Yitzchak Rabin was the victim of a political murder at a peace rally by Shalom Achshaw , with more than 100,000 participants, which took place on November 4, 1995 on the Square of the Kings of Israel (now Rabin Square) . The population of Tel Aviv was shocked to learn that the perpetrator was Jewish. This trauma broke the belief in the "innocence" of Israel for many. The city is the stronghold of the secular Jews in Israel, in which, contrary to developments in the rest of the country and especially in Jerusalem, the social democratic party Avoda and the likewise secular parties Jesch Atid and Meretz continue to determine local politics largely alone. In contrast, Bnei Berak has established itself as an orthodox or “ ultra-orthodox ” place in the greater Tel Aviv-Jaffa area. Some of the city's secular residents are now acquiring religious knowledge again in the so-called secular yeshivot . However, Liberal Judaism and Conservative Judaism in Israel in general have a difficult time. In addition, Christian free churches , such as Messianic Jews , also make religious offers.

The population of Tel Aviv, disaffected by the failed efforts to find a peace solution, is increasingly apolitical under the protection of the so-called Iron Dome, according to popular opinion . This resignation results, among other things, from the feeling, even among many left-wing voters, that Israel has “no partner for peace” on the Palestinian side. This also increases the pressure on the Israeli Arabs in Jaffa. In 2014, the Jisra'el Beitenu party called for the "voluntary resettlement" of the Arabs from "Jaffa or Acre" . It sounds similar on the part of the Tkuma party . The particularly loyal Druze also feel marginalized: 50,000 Druze and just as many Jews demonstrated in Tel Aviv on August 4, 2018 against the new nation-state law . The toughest opponents of "foreign policy" concessions in the sense of the demand "Land for Peace" made by the Israeli left are the national religious, while in Tel Aviv there is open discussion about post-ideological approaches. The political left - which built up Israel and waged several wars - is regularly referred to as “left cowards” or “traitors”; right-wing counter-demonstrators such as La Familia threaten demonstrations critical of the government in Tel Aviv. Meanwhile, a significant part of the urban population is turning away from ideological premises . Ironically alienated set pieces of Zionism and the likeness of Theodor Herzl become postmodern icons in Tel Aviv's streets .

terrorist attacks

- On October 19, 1994 (21 dead) and July 1995, public facilities in Tel Aviv were the target of terrorist attacks. Further attacks in the city followed in the spring of 1996. These attacks accompanied and undermined the peace process at that time .

- On June 1, 2000, 21 youths were murdered and dozens more seriously injured on Tel Aviv Beach when a suicide bomber blew himself up with a metal bomb.

- On January 23, 2001, the two owners of the Yuppies sushi place on Sheinkin Street in Tel Aviv, Motti Dayan (27) and Etgar Zeitouny (34), were kidnapped and murdered by Palestinians. The years 2000 to 2005 were the years of the Second Intifada .

- On February 14, 2001, a Palestinian raced into a crowd on a bus near Tel Aviv, killing eight people.

- On June 1, 2001, a 22-year-old Palestinian blew himself up in front of the Dolphinarium discotheque in Tel Aviv. 21 people were killed and over 100 injured in the suicide attack.

- On March 5, 2002, a Palestinian bomber killed three Israelis and injured more than 30 in two restaurants in central Tel Aviv. The victims were Israeli policeman Salim Barakat, 52-year-old Yosef Haybi and 53-year-old Eli Dahan.

- On March 30, 2002, a suicide bomber blew himself up in the Cafe Bialik at the intersection of Allenbystraße / King George- and Tschermichowskystraße. More than 30 people were injured, some seriously.

- On January 5, 2003, two assassins in the south of Tel Aviv blew themselves up almost simultaneously and only a few hundred meters apart. They killed 23 people and injured 100 others, and several buildings were damaged. The Islamic Jihad in Palestine and the Al Aqsa Brigades confessed to the attacks .

- On November 1, 2004, a suicide bomber set off a bomb in the Carmel market , killing three people and injuring around 30. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine took action.

- On November 10, 2014, a 20-year-old soldier was seriously injured with a knife at HaHagana train station by a perpetrator from Nablus who was allegedly acting for “nationalist motives” .

- On January 21, 2015, several people were injured in an attack on a city transport bus, five of them moderate to serious. The assassin who attacked the passengers with a knife was a 23-year-old Palestinian from Tulkarem who did not have a permit to stay in Israel. He was shot and arrested near the crime scene.

- On November 19, 2015, a Palestinian assassin stabbed two people and injured another person in an office building in southern Tel Aviv.

- On January 1, 2016, a Palestinian shot and killed two people and injured seven others in the Simta bar in central Tel Aviv . On June 8, 2016, two Palestinian bombers shot dead four people and seven others were seriously injured. The attack took place in the Sarona district in the city center.

- On February 9, 2017, in the suburb of Petach Tikwa, a 19-year-old Palestinian opened fire on visitors to a market and stabbed them with a knife. Six people were slightly injured.

climate

| Tel Aviv | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Average monthly temperatures and rainfall for Tel Aviv

Source: Israel Meteorological Service

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

mayor

Mayors of Tel-Aviv-Jaffa (until 1950 Tel Aviv) are:

| Surname | Term of office | Political party | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Meir Dizengoff | 1920-1925 | General Zionists |

| 2 | David Bloch-Blumenfeld | 1925-1928 | Achdut haAwoda |

| 3 | Meir Dizengoff | 1928-1936 | General Zionists |

| 4th | Chelouche Mosque | 1936-1936 | independently |

| 5 | Jisra'el Rokach | 1936-1953 | General Zionists |

| 6th | Chaim Levanon | 1953-1959 | General Zionists |

| 7th | Mordechai Namir | 1959-1969 | Mapai |

| 8th | Yehoshua Rabinowitz | 1969-1974 | Avoda |

| 9 | Schlomo Lahat | 1974-1993 | Likud |

| 10 | Roni Milo | 1993-1998 | Likud |

| 11 | Ron Huldai | since 1998 | Avoda |

Town twinning

The city of Tel Aviv has signed a partnership agreement with the following cities in the world (in chronological order):

|

|

Culture and sights

Tel Aviv

Architecturally, Tel Aviv offers a heterogeneous picture, the so-called White City ( Hebrew העיר הלבנה, ha-ʿir ha-lewana ), an inventory of over 4,000 buildings in Tel Aviv, most of which were built in the Bauhaus and International styles . These were built from the 1930s by numerous architects who after studying in Dessau and Berlin or Rome and Paris before the Nazis had fled. The buildings are concentrated in the districts of Kerem HaTeimanim and Merkaz Hair and have been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2003 , as they meet two of the ten possible UNESCO selection criteria. In the Dizengoff Street is the new Bauhaus Center . Guided tours to Bauhaus buildings begin here. The Beit Liebling Museum (built in 1936/1937), co-financed by the Federal Republic of Germany, and the Bauhaus Foundation Tel Aviv also deal with the Bauhaus. A few meters away are the residential museums via Chaim Nachman Bialik and Reuven Rubin , as well as the Felicja Blumental Music Center and Library in memory of Felicja Blumental and the former town hall of the city, the Beit Skora , now also a museum. The Scholem Alejchem Museum provides information about the life and work of Scholem Alejchem , an important writer of Yiddish literature . The works of his professional colleague Achad Ha'am , however, appeared in Hebrew.

Also worth seeing is the historical district of Neve Tsedek , which lies further south , on August 22, 1914, Tel Aviv's first cinema, the Eden, opened here . Four years later, the dancer Baruch Agadati gave his triumphant performance here. In the traffic-calmed district, which is now characterized by boutiques and trendy cafés, there is the museum about the painter Nahum Gutman , the Suzanne Dellal Center for Dance and Theater , the local history museum Beit Rokach , and the cultural center Neve Schechter in the Lorenz House (built in 1886) a synagogue of the Masorti movement . Not far from there is the long-neglected district of Florentin , founded by the Greek entrepreneur David Florentin. The district was a refugee camp for 53,000 displaced Jews from Thessaloniki until 1933 . At the end of the 1990s, young creative people began to convert garages and abandoned buildings into bars and studios. Alternative culture and gentrification are now increasingly displacing low-income earners and traditional furniture stores. The district is known for its street art , including the melancholy works of the Tel Aviv-born artist Know Hope, who was born in 1981 . The gallery scene is expanding into the Kiryat Hamelacha industrial area to the south of Florentin.

Independence Hall (Bet ha-ʿAzmaʾut) is located on Rothschild Boulevard . On May 14, 1948, David Ben Gurion proclaimed the State of Israel at the site of today's museum. In front of the museum there is a memorial stone for the construction of Tel Aviv with a biblical quote from the book Jeremiah ( Jer 31.4 EU ). The Tel Aviv Museum of Art shows classical and contemporary art. The Eretz Israel Museum documents history and archeology. The Beit Hatefutsot Museum documents the history of the Jews in the Diaspora . The Ben-Gurion Museum is located at the former second home of the politician . The Hagana Museum is a museum of the history of the underground Jewish organization , forerunner of the IDF Israeli army . The Palmach Museum in Ramat Aviv is dedicated to a special unit of the Hagana. It's at the Eretz Israel Museum in the north. The person Yitzhak Rabin dedicated to the Yitzhak Rabin Center . It lies between the Eretz Israel Museum and the Palmach Museum, which Rabin belonged to when he was young. A memorial by the sculptor Yael Artsi commemorates his murder on Rabin Square.

Also worth seeing is the Lutheran Immanuel Church in the American Colony founded in 1867 (המושבה האמריקאית ha-moschawa ha-Amerikait ). The Charles Bronfman Auditorium is home to the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra and, with 2,482 seats, is the largest concert hall in the city. Adjacent is the building of the Israeli National Theater Habimah, founded in Moscow in 1931 . One of his dramaturges was Max Brod , who was one of the few Jewish members of the literary intelligentsia in German-speaking countries to choose exile in Israel. While Franz Kafka , whose manuscripts Brod brought with him to Tel Aviv, learned Ivrit with a wavering resolve , an alija was not an option for Franz Werfel , who was close to them, and his escape took him via Portugal to the USA. The attitude of the Dresden professor Victor Klemperer was even more negative. He wrote: “[I] can only present intellectual history, and only in the German language and in a completely German sense. I have to live here and die here. ” Accordingly, the development of cultural life took place in an often militant demarcation from the diaspora, for example at the Tmu-na Theater, which has existed since 1944, and at the Cameri Theater . The Yiddishpiel Theater , however, has been cultivating the tradition of Yiddish theater since 1988 . From May 14th to 18th, 2019 Tel Aviv was the venue for the 64th Eurovision Song Contest , as Netta won the 2018 competition in Lisbon with her song toy . The current main direction of Israeli pop music is the Greek-Arabic influenced Mizrahi music .

Jaffa

The sights of Old Jaffa and South Jaffa include the clock tower (built in 1906), the Kikar Kedumim archaeological site , the Al-Saraya al-'Atika Palace ( Governor's New Palace ), the Jaffa Light from 1865 (Hebrew: מגדלור יפו) , the Muhamidiya Mosque , the Khan Zunana Libyan Synagogue , the Andromeda Rock, the Jaffa Museum of Antiquities , the house of the former Palestine Office at Rechov Resi'el 17, the Ilana Goor Museum , the Green House in the style of Arabic eclecticism (built 1934) and the catholic church building Sankt Peter . The Peres Center for Peace and Innovation is located on Jaffa Beach . Other sights, most of which are not open to the public, are in Jaffa's Ajami district. These include the Collège des Frères, which was founded by Lasallien monks in 1882 , the Maronite Terra Santa High School and the Catholic Saint Antony's Church, built in 1932. In the south of Jaffa the cemeteries of the Muslims and of four Christian communities are close together.

Sports

Tel Aviv is home to Israel's largest sports club, Maccabi Tel Aviv . The Maccabi basketball team has been one of the best in the European league for decades. The club's football division is the oldest and most successful in the country. Other larger sports clubs from Tel Aviv are Hapoel Tel Aviv and Bnei Yehuda Tel Aviv . In 2009 the Tel Aviv Marathon was revived after a 15-year break and has been held annually since then. The Sylvan Adams Velodrome was inaugurated in May 2018 .

economy

Tel Aviv-Jaffa is largely determined by the service sector. Another important area is diamond processing , mainly in the suburb of Ramat Gan . The city is the seat of the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange and several large banks such as Bank Leumi and Bank Hapoalim . Israeli spending on research and development is high, and much is invested in start-ups in the area between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, the country's Silicon Wadi . In 2013 the city had over 700 start-ups and was rated by the Wall Street Journal as the second most innovative city in the world after Medellin and ahead of New York City. In 2018, Tel Aviv was ranked 34th in a ranking of the world's most important financial centers. As an expression of this political and economic self-image, the term start-up nation Israel , a term coined by the book authors Dan Senor and Saul Singer 2009 was coined for the economy of Israel .

In the 2000s, the economic activities of the core city of Tel Aviv achieved shares in the region of 17% of the national gross domestic product . While the unemployment rate was 4.4% in 2011, it rose to a temporary 21% by July 2020 in connection with the global COVID-19 pandemic .

traffic

air traffic

In the surrounding area of the city is located in Lod with the Ben Gurion Airport is the largest airport in the country, which counted more than 20 million passengers a year 2017th The Sde-Dov airport, which is close to the city , has ceased operations.

Road traffic

Motorized individual traffic on the access roads is a major problem. Traffic jams are the order of the day, many access roads are chronically congested. Several motorways converge in the city area. On the highest Jewish holiday, Yom Kippur , there is no car traffic, apart from a few emergency services, from sunset to sunset for 25 hours, as a custom that even less strict believers adhere to, and without a state law, so that children and adults can walk and ride bicycles occupy the empty space of the largest multi-lane city streets at this time. In May 2020, eleven street sections in the city center were closed to car traffic and converted into pedestrian and cyclist zones. E-scooters are enjoying growing popularity.

The public transport in the Tel Aviv-Jaffa area is operated by the bus company Dan with 192 lines. In the greater Tel Aviv area, around 700,000 people use Dan's buses every day . The offer is supplemented by a close-knit network of shared taxis known as Scherut . The city is the central hub for the bus connections of the bus company Egged . The bus station Tel Aviv Central Bus Station has long been the largest in the world.

Rail transport

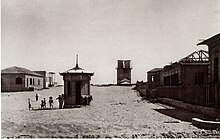

One of the terminus of the first railway line on what is now Israeli territory was located in the Jaffa district: the Jaffa – Jerusalem railway was put into operation in 1891/1892 . The station building and the surrounding buildings of Jaffa Station have been preserved as museums.

Israel Railways

Increasing individual traffic is one of the main reasons why regional rail traffic has been significantly improved and expanded by Israel Railways in recent years . Tel Aviv is on the country's main railway line, the Nahariya – Be'er Sheva line . The other routes lead to Hod Hasharon , Modi'in via Ben Gurion Airport and to Ashkelon .

Light rail

A light rail system (Tel Aviv LRT), some of which is to be run in a tunnel, has been in planning for many years with several routes. Most recently, the construction was commissioned to a Chinese consortium. The construction work on the first line ( red line ) with a length of 23 km began in August 2015. The line is to lead from the main train station in Petach Tikwa to Bat Yam . Commissioning is scheduled for 2021. In February 2017, the first preparatory work began on Ibn Gavirol Street for the construction of the Green Line , which will connect Tel Aviv to the north with Ramat Aviv and Herzelia. At the stations of the Red Line , construction is already underway across Tel Aviv, Ramat Gan and Petach Tikwa (as of February 2017). The most problematic are the costs: on the one hand, considerable cost overruns were foreseeable recently on the red line , on the other hand, the plans for the other lines are now designed for insufficient capacity due to the enormous growth in traffic in Tel Aviv.

port

Until 1965 the place was a port city (see: Port of Tel Aviv ).

education

The Tel Aviv University , the largest university in Israel, located in the district of Ramat Aviv north of the city, where previously the village of al-Sheikh Muwannis was. The second university in the metropolitan area is Bar Ilan University in Ramat Gan . Together they have more than 50,000 students. To the south of the city, in Rechovot , there is also the Weizmann Institute for Science , which in turn has more than 1000 students, mainly at doctoral level. The German Research Foundation Helmholtz Association opened its fourth international office in Tel Aviv on October 22, 2018. The aim is to further strengthen cooperation with Israeli partners. The International Union of Microbiological Societies and the Stephen Roth Institute are also based in Tel Aviv-Jaffa.

Tel Aviv also has the country's first Hebrew-language grammar school, which was named the Hebrew Herzliya grammar school in 1905 on Herzl Street in the city center in honor of Theodor Herzl . There is also the Buchmann Mehta Music School .

Personalities

Famous personalities from Tel Aviv-Jaffa include the former Israeli President Ezer Weizman , the actress Ayelet Zurer , the model Esti Ginzburg , the singers Ofra Haza and Arik Einstein , the actor Chaim Topol , the astronaut Ilan Ramon , the stage magician Uri Geller as well former Israeli Foreign and Justice Minister Tzipi Livni .

literature

Non-fiction

- Maoz Azaryahu: Tel Aviv. Mythography of a City . Syracuse University Press, Syracuse NY 2006, ISBN 0-8156-3129-4 .

- Georg Beer : Joppe . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume IX, 2, Stuttgart 1916, column 1901 f.

- Barbara E. Mann: A Place in History. Modernism, Tel Aviv, and the Creation of Jewish Urban Space . Stanford University Press, Stanford CA 2006, ISBN 0-8047-5018-1 , (Stanford Studies in Jewish History & Culture).

- Mark LeVine: Overthrowing Geography. Jaffa, Tel Aviv, and the Struggle for Palestine, 1880-1948 . University of California Press, Berkeley CA 2005, ISBN 0-520-24371-4 .

- Martin Peilstöcker, Jürgen Schefzyk, Aaron A. Burke (eds.): Jaffa - Gate to the Holy Land . Nünnerich-Asmus, Mainz 2013, ISBN 978-3-943904-13-0 .

- Stefan Boness: Tel Aviv The White City. , Ed. Jochen Visscher, JOVIS-Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-939633-75-4 .

- 100th anniversary of Tel Aviv . (PDF; 5.4 MB) PARDeS. Journal of the Association for Jewish Studies, 2009, issue 15.

Fiction

- Michael Guggenheimer : Tel Aviv. A touch of Gadol and waiting in Mersand . Edition Clandestin, Biel / Bienne 2013, ISBN 978-3-905297-42-3 .

- Etgar Keret , Assaf Gavron (eds.): With contributions by Etgar Keret, Gadi Taub , Lavie Tidhar, Deakla Keydar, Matan Hermoni, Julia Fermentto, Gon Ben Ari, Shimon Adaf , Alex Epstein , Antonio Ungar , Gai Ad, Assaf Gavron, Silje Bekeng, Yoav Katz: Tel Aviv Noir , translated by Yardenne Greenspan, Akashic Books, New York 2014, ISBN 978-1-61775-154-7 .

- Yaakov Shabtai: Memories of Goldmann . Dvorah-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1990.

Web links

- Official site of Tel-Aviv (English)

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

- Norman Ali Bassam Khalaf: Jaffa City: History and Social Situation ( Memento of February 3, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (English).

- Historical representation of old Jaffa

- Association for the promotion of the city partnership Cologne-Tel Aviv-Yafo e. V.

Individual evidence

- ↑ אוכלוסייה ביישובים 2018 (population of the settlements 2018). (XLSX; 0.13 MB) Israel Central Bureau of Statistics , August 25, 2019, accessed May 11, 2020 .

- ↑ fr: Jean-Claude Margueron , Luc Pfirsch: Le Proche-Orient et l'Égypte antiques . In: Michel Balard (ed.): Série Histoire de l'Humanité . 3. Edition. Hachette Supérieur (Hachette Livre), Paris 2005, ISBN 978-2-01-145679-3 , pp. 19 .

- ↑ Localities, Population and Density per Sq. Km., By Metropolitan Area and Selected Localities. (PDF) (No longer available online.) Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, archived from the original on April 15, 2016 ; Retrieved January 31, 2018 (English, Hebrew).

- ^ Moshe Gilad: Homes fit for a prime minister: From Ben Gurion's shack to Netanyahu's compound. In: Haaretz . May 15, 2012, accessed on August 20, 2020 .

- ^ Knesset website : The Need to Construct a Permanent Building for the Knesset, 1949-1955. Retrieved August 20, 2020 .

- ^ Basic Law of Israel . (English, wikisource.org [accessed August 20, 2020]).

- ^ Alan Berube, Jesus Leal Trujillo, Tao Ran, and Joseph Parilla: Global Metro Monitor . In: Brookings . January 22, 2015 ( online [accessed November 17, 2017]).

- ^ White City of Tel-Aviv - the Modern Movement. UNESCO World Heritage Center, accessed November 17, 2017 .

- ^ Shlomo Avineri : Zionism According to Theodor Herzl . In: Haaretz , December 20, 2002. Quotation: “'Altneuland' is […] a utopian novel written by […] Theodor Herzl, in 1902; [...] The year it was published, the novel was translated into Hebrew by Nahum Sokolow, who gave it the poetic name 'Tel Aviv' (which combines the archaeological term 'tel' and the word for the season of spring). ” In German: "Altneuland" is [...] a utopian novel, written by [...] Theodor Herzl in 1902; […] In the same year, Nachum Sokolow translated the novel into Hebrew, giving it the poetic title “Tel Aviv”, in which the archaeological term “Tel (l)” and the word for the spring season were combined.

- ↑ In Arabic one does not usually use both names together: one speaks of eitherيافا Yāfā or fromتل أبيب Tall Abīb .

- ↑ Abraham B. Yehoshua : The Struggle for the Soul of the Israeli Nation - Should the Torah or the Idea of the State Define the Jewish State? In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . No. 36 . Zurich February 13, 2012, p. 31 (translated by Ruth Achlama ).

- ^ Bernard-Henri Lévy : L'esprit du judaïsme . No. 34427 . Éditions Grasset & Fasquelle, Paris 2016, ISBN 978-2-253-18633-5 , pp. 74-83 .

- ^ Moshe Arens : One state - two languages . In: Yves Kugelmann (Ed.): Tachles - The Jewish weekly magazine . No. 37/14 . JM Jüdische Medien, Zurich, September 19, 2014, p. 10 .

- ↑ a b fr: Jean-Paul Demoule : Mais où sont passés les Indo-Européens? - Le mythe d'origine de l'Occident . In: Maurice Olender (Ed.): Points Histoire . 2nd Edition. No. 525 . Éditions du Seuil, Paris 2014, ISBN 978-2-7578-6591-0 , pp. 367 f., 405, 409 f . (édition revue et augmentée).

- ↑ a b fr: Josette Elayi : Histoire de la Phénicie . In: Marguerite de Marcillac, Mary Leroy (eds.): Tempus . Éditions Perrin, Paris 2018, ISBN 978-2-262-07446-3 , pp. 31 .

- ^ A b Damien Agut, Juan Carlos Moreno García: L'Égypte des Pharaons - De Narmer à Dioclétien, 3150 av. J.-C. – 284 apr. J.-C. In: Joël Cornette (Ed.): Collection Mondes anciens . Éditions Belin / Cente national du livre, Paris 2016, ISBN 978-2-7011-6491-5 , pp. 352 f., 365 f .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Gudrun Krämer : History of Palestine - From the Ottoman conquest to the establishment of the State of Israel . In: Beck's series . No. 1461 . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-47601-5 , p. 15, 88 f., 97 f., 149, 221, 230 f., 319, 368 (there were also outbreaks of plague in Jaffa in 1834 and 1838).