Boris treasure

Boris Schatz (born December 23, 1866 in Varniai (now Telšiai Rajongemeinde , Lithuania ), Kovno Governorate , Russian Empire ; † March 23, 1932 in Denver , Colorado ) was a Jewish sculptor, painter and teacher and became the founder of the Bezalel Academy for arts and crafts in Jerusalem . As an artist he was not of outstanding importance, even when compared with contemporary Jewish artists; but it was very well received within the Zionist movement.

Life

Vilnius (1882-1887)

Zalman Dov Baruch (Boris) Schatz came from a poor Orthodox Jewish family. In 1882 he began studying the Talmud at a yeshiva in Vilna ; After a while he also started studying art there and ran both training courses in parallel. He broke off contact with his family. As a member of the Chovevei-Zion group , he came under the influence of the writer Peretz Smolenskin . Schatz made his living by taking drawing lessons; One of his students was a Russian general who gave him Russian lessons and in whose private library he had access to works on art and culture. In the summer of 1887 he met Mark Antokolski , who was favorable to Schatz's small sculptures, but advised against going to Paris; Instead, Schatz should attend a Russian art school. Schatz then went through a personal crisis in which he joined a socialist circle and completely ceased artistic activity.

Warsaw (1888–1889)

At the beginning of 1888 he moved to Warsaw and worked as an artist again. His first work was the sculpture of an old Jew dressed in rags whom he had seen there, the target of children's ridicule. Schatz described this work as a turning point in its development, it was his "first attempt at propaganda with the means of art"; the sculpture was shown at exhibitions and brought him a certain prominence. Schatz then developed the concept that art must have a “soul” as well as a social task (“propaganda”). This became fundamental to his future work. In an article for the magazine HaTsefira (1888) he laid down his conception of art, in which he criticized the fact that Jewish art had previously concentrated on religious objects and to that extent remained handicrafts; but it must devote itself to the education of the Jewish people and develop new topics, especially pictures of important Jewish personalities in history. The significance of this text for Schatz's work is that it is his only publication prior to the founding of Bezalel. With his conception of art he was close to the Peredwischniki .

Paris (1889-1894)

At the end of 1889 Boris Schatz moved to Paris with the plan to study painting with Fernand Cormon and sculpture with Alexandre Falguière ; with that he had chosen two extremely conservative teachers. He earned his living for himself, his wife and his father-in-law by working in a ceramic factory, among other things, which increased his sense of decorative elements. In addition, he was a student and assistant to Mark Antokolski during his time in Paris. A six-month study visit to Banyuls-sur-Mer impressed Schatz with its Mediterranean nature and colors. He developed utopian plans to emigrate from the urban context with an artist community and to create fundamental works in nature for a better future humanity. Immediately after returning from Banyuls-sur-Mer, he created his most famous sculpture, Mattathias .

Sofia (1895-1905)

In 1895 Boris Schatz accepted an invitation from Prince Ferdinand to Sofia to found the Bulgarian Academy of Arts there. He followed up on Bulgarian folk art (carpet weaving, wood carving). In addition, Schatz built a museum and established industrial carpet production. The time in Bulgaria brought Schatz international fame; his works were z. B. at the international art exhibition in Paris (1900) and at the world exhibition in St. Louis (1904).

In 1903 he met Theodor Herzl in Vienna and suggested that he found an art school in Palestine.

Jerusalem (from 1906)

At the Zionist Congress of 1905 Boris Schatz was commissioned to manage a projected art school for the Yishuv ; from 1906 he lived in Palestine, where he was able to found the Bezalel Academy that same year. This was an ambitious early Zionist project. Throughout its existence, the academy has been accompanied by controversies over the question of whether it trains artists or craftsmen, the creation of a Jewish artistic style, and the distribution of competencies between Boris Schatz in Jerusalem and the Bezalel Association Board in Berlin , headed by Otto Warburg . Parallel to the work of the Academy, Schatz built the Bezalel Museum, which formed the basis for the Israel Museum, in whose collection the holdings are now integrated.

As a staunch Zionist, Schatz oriented his personal art style to the Italian Renaissance as a time of national renewal. During the First World War he was interned by the Ottoman authorities in Safed and put down his utopian ideas in the work "The rebuilt Jerusalem - a daydream". The conception of this book shows familiarity with the work News from Nowhere (1891) by the English socialist and artist William Morris , whose work Schatz probably read in German translation.

The model of the Italian Renaissance becomes evident in the public buildings planned by Schatz in Jerusalem, which are based on Filippo Brunelleschi and take on features of Florentine palazzi, including the sculpture-adorned courtyard and facade decorations in the form of majolica plaques . Schatz's visions were realized by Tel Aviv architects in the 1920s. An example of this is the Katzmann House (architect: Yosef Minor), which is similar to Brunelleschi's Ospedale degli Innocenti in Florence; the facade medallions represent biblical figures.

With portraits and sculptures of Jewish national heroes , Schatz took up another tradition of the Italian Renaissance (the uomini faminosi ), which was new in Jewish art. This also meant that the Bezalel members represented each other in works of art and z. B. Shmuel Ben-David, who died young, was portrayed on the death bed and his death mask was removed. In one arrangement, Ben-David's last work, his tools, his death mask with olive branches were put up in public; with this honor of the dead, Schatz took up the Renaissance, but there is no point of reference for this in the Jewish tradition.

The memorial plaques, which Schatz created for Zionist personalities such as Eliezer Ben-Yehuda and Theodor Herzl as part of a further Renaissance tradition , often show the relief image of the deceased in the upper arch field and below in a rectangular field an inscription that pays tribute to his contribution to society . The inscription is purely secular, without religious references, but the memorial plaque for Theodor Herzl in particular takes up religious symbolism: the flanking columns Jachin and Boaz of the Jerusalem temple , and Moses , who sees the promised land . Schatz imagined that in a future Jewish state his plaques would be displayed in public spaces and viewed by passers-by.

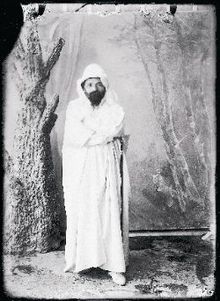

Boris Schatz walked through Jerusalem in Bedouin clothes; this shows his anti-modernist attitude and his identification with the neo-orientalism of Bezalel, which, coupled with elements of Art Nouveau, is typical for many works of the art school. Everything became an art for him, which initially promoted the academy (in 1911 there were 32 departments at the Bezalel art school), but the debts kept increasing. The Bezalel Academy had to be temporarily closed in 1927 and permanently in 1929. Boris Schatz then attempted to sell the academy's works of art at high prices abroad in order to enable Bezalel to reopen. He died on Purim in 1932 in Denver, Colorado while on a fundraising tour of the United States .

Works

His sculptural work includes busts of Antokolski , Herzl, Rubinstein and Pasteur as well as the sculptures Jeremia , Mosi's mother and Schofarbläser .

family

His children Bezalel (born 1911), Louise (born 1913) and Zoharah (born 1916) became well-known painters in Israel.

literature

- Inka Bertz: Trouble at the Bezalel: Conflicting Visions of Zionism and the Arts . In: Michael Berkowitz (Ed.): Nationalism, Zionism and ethnic mobilization of the Jews in 1900 and beyond . Conference proceedings of the Institute of Jewish Studies. Brill, Leiden / Boston 2004. ISBN 90-04-13184-1 ., Pp. 247-484.

- Ita Heinze-Greenberg: Europe in Palestine. The architects of the Zionist project 1902–1923. gta Verlag, Zurich 2012, ISBN 978-3-85676-230-8

- Dalia Manor: Art in Zion: The Genesis of Modern National Art in Jewish Palestine . Routledge, London 2005, ISBN 9780415318365

- Ori Z. Soltes: Bezalel. In: Dan Diner (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Jewish History and Culture (EJGK). Volume 1: A-Cl. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2011, ISBN 978-3-476-02501-2 , pp. 302-306.

- Armin A. Wallas (Ed.): Eugen Hoeflich . Diaries 1915 to 1927 . Vienna: Böhlau, 1999 ISBN 3-205-99137-0 , p. 269, p. 391f.

Individual evidence

- ^ The Library of Congress . Retrieved August 30, 2011

- ↑ a b c d Dalia Manor: Art in Zion: The Genesis of Modern National Art in Jewish Palestine , London 2005, p. 18.

- ↑ a b c d Ori Z. Soltes: Bezalel , Stuttgart / Weimar 2011, p. 302.

- ^ Dalia Manor: Art in Zion: The Genesis of Modern National Art in Jewish Palestine , London 2005, pp. 18-20.

- ^ Alec Mishory: Secularizing the Sacred: Aspects of Israeli Visual Culture . Brill, Leiden / Boston 2019, p. 51.

- ^ Inka Bertz: Trouble at the Bezalel: Conflicting Visions of Zionism and the Arts , Leiden / Boston 2004, p. 248 f.

- ^ Dalia Manor: Art in Zion: The Genesis of Modern National Art in Jewish Palestine , London 2005, pp. 18-20.

- ^ Inka Bertz: Trouble at the Bezalel: Conflicting Visions of Zionism and the Arts , Leiden / Boston 2004, p. 249.

- ^ Inka Bertz: Trouble at the Bezalel: Conflicting Visions of Zionism and the Arts , Leiden / Boston 2004, p. 247.

- ^ Dalia Manor: Art in Zion: The Genesis of Modern National Art in Jewish Palestine , London 2005, p. 9.

- ↑ ירושלים הבנויה: חלום בהקיץ (1918)

- ^ Alec Mishory: Secularizing the Sacred: Aspects of Israeli Visual Culture . Brill, Leiden / Boston 2019, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Alec Mishory: Secularizing the Sacred: Aspects of Israeli Visual Culture . Brill, Leiden / Boston 2019, p. 47f.

- ^ Alec Mishory: Secularizing the Sacred: Aspects of Israeli Visual Culture . Brill, Leiden / Boston 2019, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Alec Mishory: Secularizing the Sacred: Aspects of Israeli Visual Culture . Brill, Leiden / Boston 2019, pp. 54–57.

- ↑ Alexandra Nocke: The Place of the Mediterranean in Modern Israeli Identity . Brill, Leiden / Boston 2009, p. 90 f.

- ^ Inka Bertz: Trouble at the Bezalel: Conflicting Visions of Zionism and the Arts , Leiden / Boston 2004, p. 260.

- ^ Inka Bertz: Trouble at the Bezalel: Conflicting Visions of Zionism and the Arts , Leiden / Boston 2004, p. 248, note 4.

Web links

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Honey, Boris |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Honey, Zalman Dov Baruch |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Jewish sculptor, painter and teacher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 23, 1866 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Varniai , Kovno Governorate , Russian Empire , now Telšiai Rajongemeinde , Lithuania |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 23, 1932 |

| Place of death | Denver , Colorado , USA |