Sarona

Sarona ( Hebrew שָׂרוֹנָה Sarōnah ; between 1948 and 2013 circumscribed the name haQiryah [also haKirya; Hebrew הקריה HaQirjah ] spatially the same quarter) is a restaurant and nightlife district in Tel Aviv-Jaffa , Israel , framed by new multi-storey office and residential buildings. The loosened up buildings and trees in Sarona's center go back to its origin as a colony of supporters of the temple society (so-called Templars), who were mostly Germans abroad , but also Swiss and Danes abroad . The military security area, which was closed in 1940, has been successively renovated since 2006 and is open to the general public again.

history

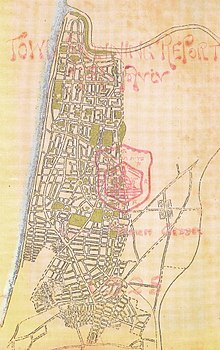

Sarona was one of the first modern villages in Palestine . Four kilometers northeast of Jaffa , at the southern end of the S (ch) aron plain , Sarona was laid out in 1871 according to floor plans and street plans by Theodor Sandels . The colonists came from the 1869 Templars purchased, previously founded three years American settlement called American Colony ( Arabic امليكان, DMG Amelīkān , English Adams City , Hebrew המושבה האמריקאית-גרמנית ביפו, transliterated: haMoschavah haAmeriqa'it-Germanit beJafo , d. H. the American-German colony in Jaffa), which is located on the northeastern edge of Jaffa. Since the Templars there was unaffordable agricultural land, they founded their third colony further northeast, Sarona, to which eighty of the 200 Templars from Jaffa moved.

When Sarona was founded, a Templar cemetery was also laid out. The site of the former Templar cemetery has been an open area east of the southern end of the Rechov Saʿadiah Ga'on since the relocation of the dead in 1952 . The Templars from Jaffa, who died before 1870, were initially buried in the cemetery of Mount Hope , a Sabbatian settlement founded in 1852 by Clorinda Minor from Philadelphia and Bergische settlers around Friedrich Großsteinbeck (1821-1858) and Johann Großsteinbeck .

Sarona's soils and climate proved to be particularly favorable for viticulture, "in autumn 1892 about 3000 hectoliters were pressed in the central cellar to Sarona ." Well-known wines were Sarona red , pearl of Jericho and Jaffa gold .

On his journey through the Holy Land , Wilhelm II reached Sarona with Entourage on October 27, 1898. The German Vice Consul in Jaffa Edmund Schmidt (1855-1916) received the emperor and greeted him warmly on behalf of the entire colony. In Sarona the emperor expressed his hope that his friendly policy towards the Ottoman Empire would help German settlements in the Levant to develop well. Vice-consul Schmidt, led by Sarona, continued the imperial couple to the (American-) German colony off Jaffa, where the couple stayed in Plato from Ustinov's Hôtel du Parc .

On November 17, 1917, British forces captured Sarona, and most of the men of German or other enemy nationality were interned in Wilhelma as enemy foreigners . In 1918 the internees were taken to a camp south of Ghaza , while the remaining inhabitants of Sarona, mostly women and children and only a few men, were placed under strict police supervision. Indian soldiers killed in the Allied conquest in 1917 found a resting place at the new Sarona military cemetery, not far from the Templar cemetery. The site of the former military cemetery has been an open space on the western side of the road in the middle section of Rechov Esriel Carlebach since the dead were reburied in 1952 .

In August 1918 the internees were transferred from Gaza to Sidi Bishr and Helwan near Alexandria . With the Treaty of Versailles , which came into force on January 10, 1920, the Egyptian camps were dissolved, and Eitel-Friedrich von Rabenau became the liquidation officer for the camp inmates. Most internees returned to the Holy Land, with the exception of those who were blacklisted by the British armed forces as undesirable.

The Occupied Enemy Territory Administration South (OETA South) confiscated all property of residents of German and other hostile nationalities. With the establishment of a regular British official apparatus in 1918, Edward Keith-Roach took over the management of the confiscated property as Public Custodian of Enemy Property and rented it out until the buildings were finally restituted to the actual owners in 1925. The Treaty of Versailles, which was signed on June 28, 1919 and entered into force on January 10, 1920 after universal ratification , legalized the existing British custody of property of Germans abroad in the Holy Land.

At the Sanremo Conference in April 1920, the Allies agreed to give Palestine into British custody, whereupon the British civil administration officially replaced the OETA on July 1, 1920. From then on, Keith-Roach transferred the rental income earned for real estate to the actual owners in his custody. The League of Nations legitimized the Allied San Remo Convention by granting Great Britain the mandate for Palestine in 1922 . The Turkey , the legal successor of the Ottoman Empire, finally legalized the British mandate by the Treaty of Lausanne , signed on 24 July 1923 and entered into force after the ratification on 5 August 1925th

This ended the custody of former enemy assets in the same year, and Keith-Roach returned it to the previous owners as legally protected property. The Templar community buried in Mount Hope, as well as some of the Templars buried in the cemetery of the Model Farm founded by Alfred Isaacs near the city's first power station, were reburied in the Templar cemetery after the residents of Sarona returned. Around 1930 the German-speaking inhabitants of the Holy Land formed a minority, within whose Jews made up the largest group, followed by around 1,300 Templars and 400 other German-speakers - with the exception of a few Catholics (mostly clergy) and even fewer non-denominationalists - predominantly Protestants.

Tel Aviv, founded in 1909, quickly grew up next to Sarona, so that the village soon became the subject of plans to expand the city. In 1931 the new German school abroad opened in Sarona . During the time of National Socialism , many residents of Sarona, like other non-Jewish Germans in the Holy Land, sympathized with the Nazi regime in Germany . In 1928 Christian Kübler opened a beer garden with wheat beer for day trippers from Jaffa or Tel Aviv. In 2014 a wheat beer bar was opened again. Sarona also had a tennis court and a bowling alley, which have also been reconstructed. The members of the NSDAP / AO based in Palestine exerted pressure on non-Jewish German owners who were willing to sell not to sell their land to Jews.

The Second World War began with the German invasion of western Poland on September 1 and the Soviet invasion of eastern Poland on September 17, 1939 , whereupon the British Mandate Government saw most of Sarona's men, insofar as they were German or other hostile nationalities, as enemy foreigners interned. The British Mandate Authorities again confiscated all property of enemy aliens and returned it to Keith-Roach as Public Custodian of Enemy Property .

In May 1940, the Mandate Government had all remaining hostile foreigners (above all non-Jewish German women and children as well as Italians and Hungarians) from Jaffa , Bir Salem , Sarona and Tel Aviv interned in Wilhelma . With the internment of the residents who initially remained in their houses in Sarona in 1940, the mandate government cleared their houses and put them to other uses. The British military built up the whole of Sarona as a secure base, and settled there. On February 21, 1946, the Haganah carried out an attack on the British military base, killing four of their men.

Many non-Jewish Germans were able to leave Wilhelma for Germany in 1941 as part of family reunification . Others moved to Australia in 1943. Interned Italians and Hungarians were released after the Peace of Paris in 1947. The former owners of Saronas, interned for a long time or in Australia or Germany, decided to sell the 1,692,102 metric Dunam Saronas. To do this, they approached the neighboring cities, which had long been interested. A trade agreement was reached and in 1947 the British mandate administration finally handled the sale of the Sarona, which had been confiscated as enemy property, to the cities of Bnei Braq , Givʿatayim , Ramat Gan and Tel Aviv in favor of the interned or emigrated former owners there . The price was paid in installments.

The British handed Sarona over to the acquiring cities in 1947. Sarona remained a military base, now the Haganah , whose Qiryati Brigade ( Hebrew חטיבת קרייתי Chaṭīvat Qirjatī ) took over the base. In the wine cellars of the Great Winery, members of the Haganah assembled 15 military aircraft from smuggled individual parts. “They were the beginnings of the Israeli Air Force .” In the Palestinian civil war , which had simmered since November 1947 , the British transferred the security of Tel Aviv against Arab raids on units of the Jewish Self defense. The remaining non-Jewish Germans in Palestine remained interned (in Wilhelma, Bethlehem in Galilee and Waldheim ) and the British evacuated them to Cyprus in April 1948 .

formerly the Aberle house

↓ Ben-Gurion's First Cabinet meets on May 1, 1949 in the Office of the Prime Minister

As haQiryah from 1948

After Sarona became part of the State of Israel, its government took over the confiscated property. "In 1948 the newly created State of Israel made the colony the seat of its government offices." The Sarona military base became the headquarters of ZaHa "L, with the seat of the Ministry of Defense and henceforth ha-Qiryah ( Hebrew הקריה HaQirjah “the campus”, “the complex”). The name is said to go back to David Ben-Gurion .

Various offices were spread across the many individual buildings. The Prime Minister of Israel also initially had his official seat ( Hebrew משרד ראש הממשלה Misrad Roš haMemšalah , German 'Office of the Head of Government' ) in one of the buildings in haQiryah, in the Wilhelm Aberles house, where the government met. From February 1949, most government agencies, except the Ministry of Defense, moved their headquarters to Jerusalem . Then in 1950 the Israeli government expropriated all confiscated German property without compensation in anticipation of a settlement of Israeli claims against Germany. Since the installments for Sarona had not yet been paid in full, Sarona also fell to the Israeli state.

The two cemeteries, located close to each other in the southwestern municipality of Saronas, were closed in 1952 and the dead reburied. The mortal remains of the dead were reburied from there, including tombstones, to the Templar cemetery in Jerusalem's Emeq Repha'im 39. Charles Lutz had represented the interests of the relatives. The Indian dead in the Sarona War Cemetery were reburied in the Commonwealth War Cemetery on Mount Scopus in Jerusalem.

The Israeli demands related to the integration of an estimated 70,000 refugees and 430,000 survivors of the Nazi persecution of Jews in Germany and Europe. The Federal Government represented the not yet fully fulfilled demands of the former owners Sarona. In 1952, on the fringes of the German-Israeli Luxembourg Agreement, both sides agreed on a procedure for recognizing and settling mutual claims.

The concrete agreement dragged on until 1962, after which the former owners of Sarona received £ 1,763,000 from its sale to the neighboring cities alone , which the British Crown Agents for the Colonies at the Anglo-Palestine Bank in favor of the former owners of Sarona who had no longer had control over it. Britain had ceded this credit, as well as a further £ 346,000, a credit of the Public Custodian of Enemy Property from renting and leasing of seized enemy property of Germans, to Israel in 1950 in return for payment. The undeveloped peripheral areas of Sarona have been developed over the years. At Rechov Kaplan, west of the village center, the Bnej-Brith-Haus, the administration of Sochnuth , the press club Beith Sokolov , the writer's house were built, while in the northwestern part of Sarona Tel Aviv's cultural forum with Hejchal HaTharbuth was built.

Sarona as a district for leisure and relaxation

As a military security area, Ha-Qiryah, the name Sarona was largely out of use for a long time, was only accessible to employees and invited visitors. Only the traffic intersected on the Rechov Eliʿeser Kaplan ( Hebrew רחוב אליעזר קפלן Rəẖōv Elīʿeser Kaplan , German ‚Eliʿeser-Kaplan-Straße ' ), an important east-west connection, haQiryah. From 2006 this traffic artery was widened, for which a Dutch company hydraulically relocated five Templar buildings, including the new Templar parish hall built in 1911 , in order to gain the necessary space.

The military treasury has sold the part of Sarona south of the street to building developers who renovated 37 historic buildings for € 120 million, redesigned the surrounding area and opened the site to the public in 2013. The developers built 17 high-rise buildings with apartments, offices and hotels around the historic core.

At the same time, to the north of the thoroughfare, new high-rise buildings created space for the military facilities, so that the Templar buildings there, too, can slowly be freed and put to new use. The Templar buildings are under monument protection and their facades may not be changed in their external appearance. The former distillery and so-called small winery now houses a restaurant run by the star chef Ran Schmu'eli .

literature

- Eduard Schmidt-Weißenfels : The Swabian colonies in Palestine . In: The Gazebo . Issue 23, 1893, pp. 379–382 and 385 ( full text [ Wikisource ]). With drawings by G. Bauernfeind .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Marina Choikhet: A piece of Germany: City history - The Templar settlement Sarona in Tel Aviv is being renovated . In: Jüdische Allgemeine , August 9, 2012, p. 5.

- ^ Ejal Jakob Eisler: The German contribution to the rise of Jaffa 1850-1914: On the history of Palestine in the 19th century . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1997, ISBN 3-447-03928-0 , footnote 378 on p. 95 (= treatises of the German Palestine Association, volume 22).

- ↑ The Templars bought some houses directly from American colonists, others from missionary Peter Metzler , who had already acquired them in the meantime. See Ejal Jakob Eisler (איל יעקב איזלר): Peter Martin Metzler (1824–1907): A Christian missionary in the Holy Land [פטר מרטין מצלר(1907-1824): סיפורו של מיסיונר נוצרי בארץ-ישראל;German]. אוניברסיטת חיפה / המכון ע"ש גוטליב שומכר לחקר פעילות העולם הנוצרי בארץ-ישראל במאה ה -19 פרסומי המכון ע"ש-גוטליב שו-. Haifa 1999, ISBN 965-7109-03-5 , p. 46 andלו (Treatises by the Gottlieb Schumacher Institute for Research into the Christian Contribution to the Reconstruction of Palestine in the 19th Century, Volume 2)

- ↑ a b c d e Avraham Lewensohn: Travel Guide Israel with street maps and city maps [Israel Tourguide, 1979; German]. Miriam Magal (ex.). Tourguide, Tel Aviv / Yapho 1982, p. 376.

- ↑ George Jones Adams and Abraham McKenzie and other colonists from Maine had reached Jaffa on September 22, 1866 and founded the American Colony in the same year . The settlement, including Tel Aviv's Lutheran Church, the Immanuelkirche , is located between today's streets Rechov Eilat (רחוב אילת) and Rechov haRabbi mi- Bacharach ( Hebrew רחוב הרבי מבכרך) in Tel Aviv-Jaffa.

- ^ A b Eduard Schmidt-Weißenfels : The Swabian colonies in Palestine . In: The Gazebo . Issue 23, 1893, pp. 380 ( full text [ Wikisource ]). With drawings by G. Bauernfeind , pp. 379–382 and 385.

- ↑ a b Vic Bentleigh: To those who have gone before us, commemorating: German cemeteries Haifa and Jerusalem / In memory of Those who have gone before us: German cemeteries in Haifa and Jerusalem . Temple Society, 1974, p. 47.

- ↑ Both were great uncle and father of John Steinbeck . Ejal Jakob Eisler (איל יעקב איזלר): The German contribution to the rise of Jaffa 1850–1914: On the history of Palestine in the 19th century . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1997, ISBN 3-447-03928-0 , p. 54 f. and footnote 203 on p. 50 (= Treatises of the German Palestine Association, Volume 22).

- ↑ The settlement of Mount Hope at Rechov haMasger 7 is now occupied by the Schevach-Moffet School, including an old plane tree from the founding time, including the former cemetery of Mount Hope. Avraham Lewensohn: Travel Guide Israel with street maps and city maps [Israel Tourguide, 1979; German]. Miriam Magal (ex.). Tourguide, Tel Aviv / Yapho 1982, p. 375.

- ^ Eduard Schmidt-Weißenfels : The Swabian colonies in Palestine . In: The Gazebo . Issue 23, 1893, pp. 381 ( full text [ Wikisource ]). With drawings by G. Bauernfeind , pp. 379–382 and 385.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Hans-Christian Rößler: A German village in Tel Aviv . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , December 23, 2014, p. 7.

- ↑ Alex Carmel (אלכס כרמל): The settlements of the Württemberg Templars in Palestine (1868–1918) 1st edition. 1973, [התיישבות הגרמניםבארץ ישראל בשלהי השלטון הטורקי: בעיותיה המדיניות, המקומיות והבינלאומיות, ירושלים: חמו"ל, תש"ל; German]. 3. Edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-17-016788-X , p. 161 (= publications of the commission for historical regional studies in Baden-Württemberg: series B, research, volume 77).

- ^ Frank Foerster: Mission in the Holy Land: The Jerusalem Association in Berlin 1852-1945 . Mohn, Gütersloh 1991, ISBN 3-579-00245-7 , pp. 134 and 136 (= missiological research; [NS], 25).

- ^ Frank Foerster: Mission in the Holy Land: The Jerusalem Association in Berlin 1852-1945 . Mohn, Gütersloh 1991, ISBN 3-579-00245-7 , p. 137 (= missiological research; [NS], 25).

- ↑ Roland Löffler: The congregations of the Jerusalem Association in Palestine in the context of current ecclesiastical and political events during the mandate . In: See, we are going up to Jerusalem! Festschrift for the 150th anniversary of Talitha Kumi and the Jerusalem Association , Almut Nothnagle (ed.) On behalf of the 'Jerusalem Association' in the Berlin Mission. Evangelische Verlags-Anstalt, Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-374-01863-7 , pp. 185–212, here p. 193. Frank Foerster: Mission in the Holy Land: The Jerusalem Association of Berlin 1852–1945 . Mohn, Gütersloh 1991, ISBN 3-579-00245-7 , p. 137 (= missiological research; [NS], 25).

- ^ A b c Frank Foerster: Mission in the Holy Land: The Jerusalem Association in Berlin 1852-1945 . Mohn, Gütersloh 1991, ISBN 3-579-00245-7 , p. 143 (= missiological research; [NS], 25).

- ↑ Roland Löffler: The congregations of the Jerusalem Association in Palestine in the context of current ecclesiastical and political events during the mandate . In: See, we are going up to Jerusalem! Festschrift for the 150th anniversary of Talitha Kumi and the Jerusalem Association , Almut Nothnagle (ed.) On behalf of the 'Jerusalem Association' in the Berlin Mission. Evangelische Verlags-Anstalt, Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-374-01863-7 , pp. 185–212, here p. 196.

- ^ Frank Foerster: Mission in the Holy Land: The Jerusalem Association in Berlin 1852-1945 . Mohn, Gütersloh 1991, ISBN 3-579-00245-7 , p. 138 (= missiological research; [NS], 25).

- ^ Frank Foerster: Mission in the Holy Land: The Jerusalem Association in Berlin 1852-1945 . Mohn, Gütersloh 1991, ISBN 3-579-00245-7 , p. 142 (= missiological research; [NS], 25).

- ↑ Roland Löffler: The congregations of the Jerusalem Association in Palestine in the context of current ecclesiastical and political events during the mandate . In: See, we are going up to Jerusalem! Festschrift for the 150th anniversary of Talitha Kumi and the Jerusalem Association , Almut Nothnagle (ed.) On behalf of the 'Jerusalem Association' in the Berlin Mission. Evangelische Verlags-Anstalt, Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-374-01863-7 , pp. 185–212, here p. 189. Frank Foerster: Mission in the Holy Land: The Jerusalem Association of Berlin 1852–1945 . Mohn, Gütersloh 1991, ISBN 3-579-00245-7 , p. 150 (= missiological research; [NS], 25).

- ^ Frank Foerster: Mission in the Holy Land: The Jerusalem Association in Berlin 1852-1945 . Mohn, Gütersloh 1991, ISBN 3-579-00245-7 , pp. 17 and 150 (= missiological research; [NS], 25).

- ↑ The power plant was located in the block between Rechov haScharon , Rechov haGalil , Rechov Salomon and Rechov haSchomron streets . Avraham Lewensohn: Travel Guide Israel with street maps and city maps [Israel Tourguide, 1979; German]. Miriam Magal (ex.). Tourguide, Tel Aviv / Yapho 1982, p. 378.

- ↑ In addition to clergy, three German Catholic families lived in Jerusalem in 1900, two in Tabgha , one in Jaffa and some in Haifa. ʿAbd-ar-Raʿūf Sinnū (Abdel-Raouf Sinno,عبد الرؤوف سنّو): German interests in Syria and Palestine, 1841–1898: Activities of religious institutions, economic and political influences . Baalbek, Berlin 1982, ISBN 3-922876-32-3 , p. 222 (= Studies on the Modern Islamic Orient, Volume 3).

- ↑ Lissy Kaufmann: Swabia in Israel: Create, create, build houses . In: Der Tagesspiegel , April 12, 2015.

- ^ Ralf Balke: Swastika in the Holy Land: the NSDAP regional group Palestine . Sutton, Erfurt 2001, ISBN 3-89702-304-0 , p. 67 f.

- ^ A b c Frank Foerster: Mission in the Holy Land: The Jerusalem Association in Berlin 1852-1945 . Mohn, Gütersloh 1991, ISBN 3-579-00245-7 , p. 184 (= missiological research; [NS], 25).

- ↑ Paul Sauer: From the land around the Asperg in the name of God to Palestine and Australia: The checkered history of the temple society . Verlag der Tempelgesellschaft, Stuttgart 1995, p. 22 (= Writings of the Tempelgesellschaft, issue 1)

- ↑ Cf. Article 7, sentence 2 in the contract between the Australian Federation and the Federal Republic of Germany on the distribution of the compensation paid by the government of the State of Israel for German secular property in Israel between Australia and Germany of April 21, 1965, in: Bundesgesetzblatt 1965 / II 1305 as well as in: United Nations Treaties Series , Volume 448, p. 227 ff.

- ↑ Avraham Lewensohn: Guide Israel with maps and city maps [Israel Tour Guide, 1979; German]. Miriam Magal (ex.). Tourguide, Tel Aviv / Yapho 1982, p. 383.

- ↑ Jewish Germans who lived in Palestine had usually either given up their German citizenship by then or had been expatriated through various Nazi measures . Even if they still had citizenship, the British did not see Jewish Germans as potential supporters of the Nazi regime. Through the Eleventh Ordinance to the Reich Citizenship Law of November 25, 1941 ( RGBl. I, p. 722), all Jewish Germans who left the country, were deported there or were already staying there were automatically expatriated.

- ↑ a b Avraham Lewensohn: Guide Israel with maps and city maps [Israel Tour Guide, 1979; German]. Miriam Magal (ex.). Tourguide, Tel Aviv / Yapho 1982, p. 384.

- ↑ a b Vic Bentleigh: To those who have gone before us, commemorating: German cemeteries Haifa and Jerusalem / In memory of Those who have gone before us: German cemeteries in Haifa and Jerusalem . Temple Society, 1974, p. 44.

- ↑ He was a diplomat from Switzerland, who took on the Germans there on behalf of Germany from the beginning of the war and sent him to Jaffa as consul from 1935 to 1940, where he was responsible for this task until he was called up in 1940 in Bern. See Rolf Stücheli: Lutz, Carl. In: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz ., Accessed on April 11, 2017.

- ↑ Vic Bentleigh: To those who have gone before us, commemorating: German cemeteries Haifa and Jerusalem / In memory of Those who have gone before us: German cemeteries in Haifa and Jerusalem . Temple Society, 1974, p. 1 f.

- ↑ On the numbers: Niels Hansen : From the shadow of the catastrophe: The German-Israeli relations in the era of Konrad Adenauer and David Ben Gurion. A documented report with a preface by Shimon Peres . Droste, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-7700-1886-9 , p. 186 (= research and sources on contemporary history, volume 38).

- ^ Agreement between the Government of the State of Israel and the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany of September 10, 1952 . In: Bundesanzeiger , No. 70/53 and in: United Nations Treaties Series . Volume 345, p. 91 ff.

- ↑ Niels Hansen: From the shadow of the catastrophe: The German-Israeli relations in the era of Konrad Adenauer and David Ben Gurion. A documented report with a preface by Shimon Peres . Droste, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-7700-1886-9 , p. 267 (= research and sources on contemporary history, volume 38).

- ^ Agreement on German secular property in Israel of June 1, 1962, in force from August 13, 1962, announced on September 13, 1962 in the Federal Gazette , No. 195/62, which stipulates Israeli payments totaling 54 million DM . The distribution of the Israeli compensation payments between the former owners in Germany and Australia is regulated by the agreement between the Australian Confederation and the Federal Republic of Germany on the distribution of the compensation paid by the government of the State of Israel for German secular property in Israel between Australia and Germany from 21. April 1965. In: Bundesgesetzblatt , 1965 / II 1305 and in: United Nations Treaties Series , Volume 448, p. 227 ff.

- ↑ After conversion this was DM 5,691,664 in 1965; see. Article 3, sentence 2 (b) in the contract between the Australian Confederation and the Federal Republic of Germany on the apportionment of the compensation paid by the government of the State of Israel for German secular property in Israel between Australia and Germany of April 21, 1965. In: Bundesgesetzblatt , 1965 / II 1305 and in: United Nations Treaties Series , Volume 448, p. 227 ff.

- ↑ See Article 6, Clause 2 in the Treaty between the Australian Federation and the Federal Republic of Germany on the distribution of the compensation paid by the government of the State of Israel for German secular property in Israel between Australia and Germany of April 21, 1965. In: Bundesgesetzblatt , 1965 / II 1305 and in: United Nations Treaties Series , Volume 448, p. 227 ff.

- ↑ a b See Article 5, sentence (e) in the Agreement for the settlement of financial matters outstanding as a result of the termination of the Mandate for Palestine of March 30, 1950. In: United Nations Treaties Series , Volume 86, p. 231–265, here p. 239 ff.

- ↑ The former owners affected by British confiscation received the latter amount in Israel as compensation for lost use of their property located in places other than Sarona. After conversion, that was 1,098,336 DM in 1965; see. Article 7, sentence 1 in the contract between the Australian Federation and the Federal Republic of Germany on the distribution of the compensation paid by the government of the State of Israel for German secular property in Israel between Australia and Germany of April 21, 1965. In: Bundesgesetzblatt , 1965 / II 1305 and in: United Nations Treaties Series , Volume 448, p. 227 ff.

- ↑ Avraham Lewensohn: Guide Israel with maps and city maps [Israel Tour Guide, 1979; German]. Miriam Magal (ex.). Tourguide, Tel Aviv / Yapho 1982, p. 385.

Coordinates: 32 ° 4 ′ N , 34 ° 47 ′ E