Versailles Peace Treaty

The Treaty of Versailles (also Versailles Treaty, Peace of Versailles ) was negotiated at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 in the Palace of Versailles by the powers of the Triple Entente and their allies until May 1919. With the signing of the peace treaty , the First World War ended in terms of international law . It was also the founding act of the League of Nations .

As early as November 11, 1918, the Compiègne armistice had ended the fighting of the First World War, but not the state of war . The German delegation was not allowed to take part in the negotiations, but was only able to effect a few amendments to the content of the contract by means of written submissions. The treaty established the sole responsibility of Germany and its allies for the outbreak of the world war and obliged it to cede territories, disarm and pay reparations to the victorious powers . At the ultimate request, Germany signed the treaty on June 28, 1919 in protest in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles . After ratification and the exchange of the documents, it came into force on January 10, 1920. Because of its seemingly harsh conditions and the way in which it came about, the majority of Germans perceived the treaty as an illegitimate and humiliating dictate .

In addition to Germany, the signatories included the United States (USA), the United Kingdom , France , Italy , Japan , Belgium , Bolivia , Brazil , Cuba , Ecuador , Greece , Guatemala , Haiti , Hejaz , Honduras , Liberia , Nicaragua , Panama , Peru , Poland , Portugal , Romania , the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes , Siam , Czechoslovakia and Uruguay .

China , which had been at war with Germany since 1917, did not sign the treaty.

The United States Congress refused the Treaty of Versailles in 1920, the ratification . The United States did not join the League of Nations and concluded a separate peace with Germany in 1921 , the Berlin Treaty .

As further Paris suburban contracts with the losers followed on September 10, 1919 the Treaty of Saint-Germain with German Austria , on November 27, 1919 the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine with Bulgaria , on June 4, 1920 the Treaty of Trianon with Hungary as well on August 10, 1920 the Treaty of Sèvres with the Ottoman Empire .

Origin and Ratification

The treaty was the result of the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 , which met in the Palace of Versailles from January 18, 1919 to January 21, 1920. The place and the opening date were not chosen by chance: in 1871, during the siege of Paris , German dignitaries made the imperial proclamation in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles . This reinforced (among many other factors, for example France's high reparations to Germany) the Franco-German hereditary enmity and French revanchism (“ Toujours y penser, jamais en parler ”). France's Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau hoped that the location would heal a national trauma.

This was preceded by US President Woodrow Wilson's 14-point program on January 8, 1918 , which, from a German perspective, formed the basis for the Compiègne armistice on November 11, 1918, which was initially limited to 36 days .

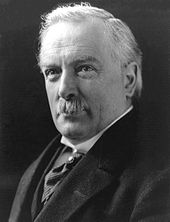

A select committee of the Congress, the so-called Council of Four , which included US President Woodrow Wilson, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau , British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and Italian Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando met beforehand. The Council defined the main points of the treaty. Only the victorious powers took part in the oral negotiations ; only memoranda were exchanged with the German delegation . The result of the negotiations was finally presented to the German delegation as a draft contract on May 7, 1919 - not by chance on the anniversary of the sinking of the RMS Lusitania . The German delegation - which also included Professors Max Weber , Albrecht Mendelssohn Bartholdy , Walther Schücking and Hans Delbrück, as well as General Max Graf Montgelas - refused to sign and urged that the provisions be mitigated, whereby the German delegation was not allowed to take part in the oral proceedings has been; instead, notes were exchanged. The referendum in Upper Silesia was one of the few amendments to the mantle note presented by the Allies on June 16 . The victorious powers did not allow further improvements and ultimately demanded the signature. Otherwise they would send their troops to Germany. The Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Forces, Marshal Ferdinand Foch , had worked out a plan for this: From the already occupied Rhineland, the troops of the Entente were to advance along the Main to the east, in order to reach the Czech border by the shortest possible route and thus to separate northern and southern Germany separate. In circles around the Upper President of East Prussia, Adolf von Batocki , the Social Democrats August Winnig and General Otto von Below , plans were developed to flatly reject the peace conditions and leave West Germany to the advancing troops of the victorious powers without a fight. In the Prussian eastern provinces, where the Reichswehr was still relatively strong, an eastern state was to be founded as a center of resistance against the Entente. Prime Minister Philipp Scheidemann resigned on June 20, 1919 . On May 12, 1919, he had already expressed his position in the Weimar National Assembly with the question that has become a household word :

"Which hand should not wither that put itself and us in such chains?"

Under the pressure of the impending invasion and the continued British naval blockade despite the armistice , which raised fears of a dramatic deterioration in the food situation, the National Assembly voted on June 22, 1919 with 237 votes to 138 for the acceptance of the treaty. Scheidemann's party friend and successor Gustav Bauer exclaimed at the meeting:

“We stand here out of a sense of duty, knowing that it is our damned duty to seek to save what can be saved [...]. If the government [...] signs with reservations, it emphasizes that it is giving way to violence, resolving to start a new war for the unspeakably suffering German people, the disruption of their national unity through further occupation of German territory, appalling famine for women and children and to spare relentless prolonged restraint by prisoners of war. "

Foreign Minister Hermann Müller ( SPD ) and Transport Minister Johannes Bell ( Zentrum ) therefore signed the contract on June 28, 1919, in protest.

The representatives of the USA, the most important signatory power alongside Great Britain and France, were the first to sign the treaty after the two German delegates, but the American Congress did not ratify the treaty. On November 19, 1919 and again on March 19, 1920, the treaty and membership of the United States in the League of Nations were rejected. The USA therefore signed the Berlin Treaty of August 25, 1921 with Germany .

Starting conditions

Two of the most important powers from the beginning of the war no longer existed:

- As a result of the October Revolution , made possible by the infiltration of Lenin by the German Reich, Soviet Russia had now emerged on the soil of the Russian Empire . The capitalist states now feared that the Soviet state, committed to the world revolution , would threaten the internal political stability of all other states.

- The Austro-Hungarian Danube Monarchy fell apart at the armistice .

Both warring parties had taken advantage of nationality problems in opposing states: The Central Powers had founded Regency Poland on the territory of the Tsarist Empire and tolerated the founding of Lithuania benevolently. The Allies and the Slavic minorities of the Danube Monarchy had supported each other and were now committed to each other.

A general return to the pre-war borders was impossible and the reorganization was burdened with the problems that the demarcation of borders between nation-states inevitably brings with it.

By far the heaviest war damage to civilian infrastructure was recorded in France and Belgium, which was attacked by Germany .

Goals of the victorious powers

The goals of France, Great Britain, and the United States differed considerably; the French were often at odds with those of the two Anglo-Saxon powers.

France

Clemenceau's colleague André Tardieu summed up France's goals at the Versailles Peace Conference as follows:

“Creating security was the first duty. Organizing the reconstruction was the second. "

During the Franco-Prussian War and the First World War , large swathes of France had become a theater of war . Therefore, it was Clemenceau's primary goal, in addition to the return of Alsace-Lorraine , which was taken for granted, in a next war with Germany, to make a new invasion of German armed forces impossible from the outset. To this end, he strove for the Rhine border and the greatest possible weakening of Germany. This went hand in hand with its second goal: to compensate for the destruction caused by the war and to cover the inter-allied debts that France owed mainly to the United States. Complete coverage of all the expenses that the war had brought seemed entirely suitable to weaken the dangerous neighbor in the long term.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom had suffered far less from the war than France, but it had also borrowed heavily from the United States to finance its participation in the war . In view of developments in Russia , the British government wanted to avoid a power vacuum in Central Europe and therefore not to weaken Germany too much in the sense of the classic balance of power strategy. The British government wanted to permanently weaken the German position overseas after the German Empire had upgraded its fleet and had intensified its colonial policy from around 1890 . The British position becomes clear in a memorandum from Prime Minister Lloyd George of March 1919:

“One may rob Germany of its colonies, reduce its armament to a mere police force and its fleet to the strength of a power of the fifth rank. Nevertheless, if Germany feels that it was treated unfairly in the peace of 1919, Germany will ultimately find means of forcing its overcomers to return. […] To obtain remuneration, our conditions may be strict, they may be harsh and even ruthless, but at the same time they can be so just that the country we impose them on feels within itself that it has no right to complain . But injustice and presumption, displayed in the hour of triumph, will never be forgotten or forgiven. [...] I can think of no stronger reason for a future war than that the German people, who have certainly proven to be one of the most powerful and powerful tribes in the world, would be surrounded by a number of smaller states, some of which never were before was able to set up a stable government for itself, but each of which contained large numbers of Germans who wanted reunification with their homeland. "

Lloyd George's financial claims were originally intended to cover only British war costs. Public opinion in Great Britain was strongly angry against Germany as a result of the war, which was shown not least in the so-called khaki elections , the general election of December 14, 1918 . Under strong domestic political pressure, Lloyd George had agreed that the reparations imposed on Germany should also include the value of all pensions for invalids and war survivors, which increased the amount of reparation claims enormously.

Italy

The Kingdom of Italy was very hesitant and only entered the war on the side of the Triple Entente as a result of the secret London treaty of 1915 and the prospect of territorial gains in it , but took the chance to win the last " Irredenta " areas of Trentino and Trentino Adding Trieste to Italian territory , gaining an easily defensible northern border on the Brenner and a colony ( Dodecanese ). Italian claims were therefore essentially included in the treaty texts of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and Sèvres .

United States

American war aims were the lifting of all trade restrictions and the freedom of shipping, the violation of which by Germany's unrestricted submarine warfare had prompted the United States to enter the war. In addition, President Wilson sought a just peace order that would make another world war impossible. In January 1918 he published a draft of such a peace order, which also contained the other American war aims, with his fourteen-point program . It postulated, among other things, the prohibition of any secret diplomacy , the right of peoples to self-determination , extensive disarmament , a League of Nations , the withdrawal of the Central Powers from all occupied territories and the restoration of Poland , which was to have access to the sea. Some of these demands were not compatible; At that time there was nowhere a Polish majority on the Baltic coast, which is why the Polish corridor to the Baltic Sea , which was later created in the Versailles Treaty, violated the peoples' right of self-determination. On the basis of these demands, Wilson sought a mutual agreement without a winner and a defeated, but moved away from it after the German “dictation peace” of Brest-Litovsk .

In addition, Wilson advocated self-determination as an indispensable principle for action.

content

Territorial Regulations

The empire had to cede numerous areas: Northern Schleswig to Denmark , most of the provinces of West Prussia and Posen as well as the Upper Silesian coal mining area and smaller border areas of Silesia and East Prussia to the new Polish state, the Second Republic . In addition, the Hultschiner Ländchen fell to the newly formed Czechoslovakia. In the west, the territory of the realm of Alsace-Lorraine went to France, and Belgium received the Eupen - Malmedy area, which also had a predominantly German-speaking population. Overall, the empire lost 13% of its previous area and 10% of the population. In addition, the entire imperial German colonial possessions were placed under the League of Nations, which handed them over to interested victorious powers as mandate areas . The German Reich had to recognize Austria's sovereignty. The merger with the German Reich sought by German Austria was prohibited in Article 80 of the Versailles Treaty. This connection ban was also found in Article 88 of the Treaty of Saint-Germain.

German territorial losses due to the Versailles Treaty

Immediately ceded areas (without referendum)

- Alsace-Lorraine to France

- Almost all of West Prussia ( 10th century to 1308 and 1466 to 1772 as a Prussian royal share belonging to the Kingdom of Poland ) to Poland, but without Danzig , the Marienwerder voting area , the part of the city and district of Elbing east of the Nogat , the Deutsch Krone districts , Flatow (remaining circle) and Schlochau

- Province of Poznan ( 9th century to 1793 and 1807 to 1815 as historical landscape Greater Poland Polish) to Poland, but without two smaller German-speaking peripheral areas in the west

- the southern half of the East Prussian district of Neidenburg

- the Reichthaler Ländchen to Poland

- small border strips between Lower Silesia and Poland

- the Hultschiner Ländchen to Czechoslovakia

- New Cameroon , which had only become part of the German colony of Cameroon through an exchange in 1911 , was returned to France

- the lease area Kiautschou in China under a Japanese mandate (this decision, which ignored the Chinese demand for the return of the colony, triggered the May 4th Movement in China and resulted in the conclusion of a separate peace with Germany on May 20, 1921)

- the archipelagos of the Mariana Islands (Spanish since 1556) and the Carolines acquired by Spain in 1899 , both under a Japanese mandate

Released after referendums in the wake of the Versailles Treaty

Reich border from 1918 and Upper Silesian districts Lower Silesian Districts

- North Schleswig voted for Denmark with a three-quarters majority ; the southern part of Schleswig's voting area remained with Germany with a majority of 80 percent.

- During the referendum on March 20, 1921 , Upper Silesia was occupied by Allied troops to prevent German authorities from exerting pressure to the detriment of the Polish option. 60 percent of those entitled to vote voted to remain with the German Reich. After a violent Polish uprising had failed due to the resistance of German Freikorps , the Supreme Council of the Allies decided in October 1921 to divide the voting area, a possibility that the Versailles Treaty explicitly provided for. On June 20, 1922 , an area of about a third of the area in Eastern Upper Silesia , where Poland had a majority of the votes, was given to Poland. So far, almost a quarter of German hard coal had been mined in the ceded part . The separation made many Germans bitter because the division was only decided after the vote and the greater part of the industrially valuable Upper Silesian industrial area went to Poland. Due to the spatial heterogeneity of the majority of votes, several places fell to Poland, contrary to the respective majority of votes. The artificiality of the demarcation in this metropolitan area, partly through industrial companies and mines, fed the bitterness.

- Eupen-Malmedy and the previous Neutral Moresnet to Belgium ; originally without a vote, a later vote confirmed belonging to Belgium. Whether the vote was correct or not was presented contradictingly by both sides. The ceded area included communities with French-speaking ( Malmedy , Weismes ) as well as with German-speaking population groups ( Eupen , Sankt Vith and others). The latter form the German-speaking Community of Belgium today .

Remained with the German Reich after referendums in the wake of the Versailles Treaty

- South Schleswig

- the western part of Upper Silesia including the part of the Lower Silesian district of Namslau that is included in the voting area (two thirds of the voting area)

- after the referendums in East and West Prussia on June 11, 1920 parts of four districts of West Prussia east of the new Polish "corridor" (→ West Prussia ) and the southern part of East Prussia (without Soldau , Neidenburg district )

Subordinated to the League of Nations

- The Saar area , whose coal production (see mining in Saarland ) fell to France, was placed under the League of Nations. After 15 years there was to be a vote on state membership , which on January 13, 1935, resulted in a large majority in favor of Germany.

- Danzig and its surroundings were declared a Free City under the control of the League of Nations, included in the Polish customs area and represented by Poland in foreign policy.

- The Memel country was placed under control of the League its own State with a French prefect and on 10 January 1923 by Lithuania occupied. In 1924 it was placed under Lithuanian sovereignty as an autonomous region in the Memel Convention of the League of Nations.

- the German colonies

Temporary occupied by the victorious powers

- The Rhineland ; the evacuation should take place by 1935 at the latest. This limitation of the Allied occupation of the Rhineland was difficult for the Anglo-Saxons to wrest from the French, whose original aim had been to separate the Rhineland from the Reich. In order to guarantee France's security against Germany even without such a massive violation of the peoples' right to self-determination, the USA and Great Britain concluded a guarantee agreement with the French Republic that declared every new German attack on France to be a casus belli . This guarantee agreement, like the entire treaty, was not ratified by the American Congress, which is why the British refrained from doing so.

Effect of territorial losses on citizenship

According to Article 91 of the Versailles Treaty, in principle all German Reich citizens who had their place of residence in the areas that were finally recognized as part of the re-established Polish state acquired Polish citizenship by law , losing their German citizenship . Two years after the entry into force of the Treaty here resident over 18 years old were German nationals entitled to opt for German nationality. Poles of German nationality over the age of 18 who were resident in Germany were entitled to opt for Polish nationality. All persons who made use of the option right were free to move within twelve months to the state for which they had opted. They were allowed to take all their movable goods with them duty-free. They were free to keep any real estate they owned in the territory of the other state in which they lived prior to the option.

In the first few years after the transformation into domestic law, these provisions created a not inconsiderable migration movement between the German Reich and Poland. Many Germans who did not want to lose their German Reich and citizenship and had opted accordingly, saw themselves forced to leave their ancestral homeland and also to sell their property in order to rebuild an existence in the Reich. Poland viewed those who had temporarily emigrated in the post-war confusion as tacit optants, even if these Germans had not yet decided for or against German citizenship. The resulting increased supply on the Polish real estate market led to falling prices for the real estate and property losses among sellers.

As a result of the Vienna Agreement , around 26,000 Germans emigrated from the new Polish state between 1924 and the summer of 1926, partly voluntarily and partly by force. The German Reich was ill-prepared to accept these people. Most of them were initially caught in a camp near Schneidemühl .

Military Regulations

In the preamble to the fifth part of the treaty, the "Provisions on Land Army, Maritime Power and Aviation" (Articles 159 to 213), it was declared that Germany "in order to allow the beginning of a general restriction on the armaments of all nations" to be precise Obligation to comply with the following provisions on land, sea and air forces.

- Professional army with a maximum of 100,000 men including a maximum of 4,000 officers

- no general conscription

- Dissolution of the Great General Staff

- Restriction to a single service period of twelve years without the possibility of re-engagement, a maximum of 5% of the teams are allowed to retire early each year (this should prevent clandestine military service)

- Ban on military associations, military missions and mobilization measures

- Navy with 15,000 men , six armored ships, six cruisers , 12 destroyers and 12 torpedo boats

- no heavy weapons like submarines , tanks , battleships

- Ban on chemical warfare agents

- Limitation of weapons stocks (102,000 rifles, 40.8 million rifle cartridges)

- Ban on the reconstruction of air forces

- Demilitarization of the Rhineland and a 50 kilometer wide strip east of the Rhine

- Prohibition of the construction of fortresses along the German border

- Ban on fortifications and artillery between the Baltic and North Sea

- Furthermore, any measures that were considered suitable for preparing for war were banned. Among other things, this had an impact on the German Red Cross , which subsequently had to put its original task in the background.

Article 177 of the treaty required the surrender or notification of all military weapons in civilian possession. The German Reichstag subsequently passed the majority of the Disarmament Act on August 5, 1920 (at that time the Fehrenbach cabinet ruled ).

In Section IV., Articles 203 to 210 laid down the establishment and functioning of "Interallied Monitoring Committees" for the purpose of monitoring compliance with these provisions.

Criminal provisions

The seventh part of the treaty provided for criminal provisions for German war criminals . In particular, the former Kaiser Wilhelm von Hohenzollern was to be tried “for the most serious violation of international morality and the sanctity of the treaties” before a specially established court of the victorious powers. Germany had to agree to extradite anyone charged with war crimes.

War Guilt Article (Article 231) as the basis for reparation claims

Article 231 says:

“The Allied and Associated Governments declare, and Germany recognizes, that Germany and its allies are responsible as originators for all losses and damages suffered by the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals as a result of the war suffered by the attack by Germany and its allies was forced to have suffered. "

The treaty assigned Germany and its allies alone the role of aggressor in World War I. It meant an initial isolation of Germany, which saw itself as a scapegoat for the mistakes of the other European states before the world war.

The unilateral assignment of guilt to Germany triggered the war guilt debate there . The signatures by Hermann Müller and Johannes Bell, who had taken office through the Weimar National Assembly in 1919, nourished the stab-in-the-back legend propagated primarily by Paul von Hindenburg and Ludendorff and later by Adolf Hitler .

Historians today judge the causes of the First World War in a more nuanced manner than is expressed in the treaty. Article 231 was not intended to evaluate historical events, but to legally and morally legitimize the unfavorable peace conditions for the German Reich. In addition, the German Reich was to be made financially responsible for the damage to land and people that the imperial troops had caused, especially in France. The Treaty of Versailles therefore laid the groundwork for the reparations claims against the German Reich, the amount of which was not initially determined. The representatives of the German Reich protested against Article 231 not only for reasons of self-justification, but with the aim of undermining the moral basis of the opposing demands as a whole. The German reparations after the First World War weighed on the new republican state; they were one of several causes of inflation in the following years up to 1923.

Economic provisions and reparations

The German Reich was obliged to make reparations through payments in cash and in kind in the amount still to be determined by the Reparations Commission . An initial installment of 20 billion gold marks was payable by April 1921. In addition, a reduction in the size of the Imperial German merchant fleet was stipulated. The major German shipping routes, namely the Elbe , Oder , Danube and Memel , were declared international. For five years, the German Reich had to unilaterally grant the victorious powers most-favored nation treatment . In the so-called champagne paragraph 274, it was stipulated that product names, which were originally designations of origin from the countries of the victorious powers, could only be used if the so-called products actually came from the region mentioned: Since then, brandy is no longer allowed in Germany as cognac and sparkling wine are no longer sold as champagne - names that were quite common in German countries until then. Luxembourg had to give up the previously existing customs union with the German Empire.

League of Nations

The treaty also provided for the creation of the League of Nations , one of President Wilson's stated goals. The League of Nations was the forerunner organization of today's United Nations , which was founded after the Second World War . Germany was not a member until 1926.

International labor organization

The International Labor Organization (ILO) was also brought into being through the Versailles Treaty (Chapter XIII) , which is still in existence today. The regulations on this organization are also contained in all Paris suburb contracts and for the first time raise problems in the world of work to the level of the international legal system. The Versailles Treaty thus goes beyond the rules of traditional peace treaties.

Guarantee terms

As a guarantee for the implementation of the remaining provisions of the treaty, an allied occupation of the area on the left bank of the Rhine and additional bridgeheads at Cologne , Koblenz and Mainz were agreed. This should be repealed in stages 5, 10 and 15 years after the ratification date (Articles 428-430).

consequences

The contract was largely implemented. Exceptions were the penal provisions and the reparation claims: Instead of covering the entire war costs of the victorious powers including widow's and orphan's pensions as well as inter-allied war debts, the German Reich officially paid a total of only 21.8 billion gold marks. The suspected war criminals were almost completely punished. The Netherlands granted the former emperor asylum and refused to extradite him. The other alleged war criminals were included on a list of the victorious powers, which included 895 people, including such prominent as the former Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg , the former Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia , Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz , Hindenburg and Ludendorff. In 1920, however, they waived their transfer against the assurance of the Reich that war criminals would be tried before the Reichsgericht . The Leipzig trials , which were carried out in 1921, remained mere show trials; they did not represent a serious attempt to punish war crimes.

The economic power of the German Reich was considerably weakened by the territorial cessions. Large parts of its heavy industry were hit. It lost 80% of its iron ore deposits , 63% of its zinc ore deposits, 28% of its coal production and 40% of its blast furnaces . The loss of Poznan and West Prussia reduced the arable land by 15%, the grain harvest by 17% and the livestock by 12%. German agriculture was initially unable to compensate for this loss. Germany's population decreased by seven million people (11%), of which about one million poured into the empire in the following years, mainly from Alsace-Lorraine and the areas ceded to Poland. German foreign trade was severely affected by the loss of 90% of the merchant fleet and all of the foreign assets.

Since the German Reich had to reduce its army to 115,000 soldiers (100,000 armies and 15,000 navies) according to Art. 159 ff. Versailles Treaty, it was not able to militarily prevent a possible Allied invasion. As early as 1921, the victor states threatened in the London ultimatum with an occupation of the Ruhr area; In 1923 it was actually occupied by Franco-Belgian troops (→ occupation of the Ruhr ).

Various historians described it as a basic problem of the Versailles Treaty that it tried to achieve two goals at the same time: on the one hand, the ideals of the self-determination of peoples and territorial agreement between people and state, represented by Wilson, and, on the other hand, the intentions of the victorious powers, especially France, to weaken the German Reich decisively.

Sebastian Haffner wrote after the Second World War that the German Reich was still the strongest and geographically located in the middle, that is, European power that was indispensable for the stability of the continent was "neither permanently disempowered nor permanently integrated".

The Treaty of Versailles - sometimes called the " Carthaginian Peace " - was too harsh for Germany to be accepted by a German Empire that would continue to exist as a political unit and economic great power. Nonetheless, he left it powerful enough that less than 20 years later a German government could translate ideas of revenge into politics, thereby plunging Europe into the catastrophe of World War II. Marshal Foch said at the time the treaty was signed: “This is no peace. This is a twenty-year armistice. ”- Foch had advocated the smashing of the German Reich.

John Maynard Keynes , the Treasury representative of the UK delegation at the treaty negotiations, resigned from his post on the delegation before the negotiations were concluded, protesting the terms of the treaty that were to be imposed on Germany. On the advice of the South African conference participant Jan Christiaan Smuts , he wrote a book on the economic consequences of the peace treaty , in which he stated that the payment obligations imposed on Germany would both destabilize international economic relations and result in greater social explosives for Germany.

The peace conditions in Germany were perceived as surprising and extremely tough. For a long time, the German public had believed that they could achieve a mild peace on the basis of Wilson's Fourteen Points, which would essentially restore the status quo ante . The cultural philosopher Ernst Troeltsch wrote that Germany had found itself in the "dream land of the armistice period", from which it had been brutally awakened with the publication of the peace conditions. In addition, there was the fact that the victorious powers had excluded the German Reich from the negotiations and only allowed it to make written submissions at the end : the catchphrase of the “ Versailles dictate ” made the rounds. These two factors contributed to the fact that the resistance of the Reich government to the treaty, as historian Hans-Ulrich Wehler writes, “was borne by an almost complete consensus throughout the country”. In the following years, the revisionism of this treaty was a declared goal of German foreign policy: Neither the legitimacy of the peace nor the fact that Germany had lost the war militarily (→ stab in the back legend ) was accepted. All the governments of the Weimar Republic tried in different ways to “throw off the shackles of Versailles”, which is why one can speak of a veritable “Weimar revision syndrome”. In addition to the way in which it came about and the content of the treaty - especially the assignment of territory with German population groups - this revision syndrome permanently damaged the reputation of the democratic western powers and trust in the new democracy in Germany. Some historians see the treaty as an important cause of the rise of National Socialism . As expressed Theodor Heuss , then liberal member of parliament in 1932 in his book Hitler's way : "The starting point of the Nazi movement is not Munich, but Versailles."

The German government attempted to react to the high reparation claims and the industrial dismantling in the Ruhr area with a general strike, which was to be supported with constantly printed money. This fueled inflation to a hyperinflation that plunged large parts of the population into hardship and misery. It was mainly due to the fact that the war bonds, with which the German Empire had previously financed the war, were not matched by real assets due to the military defeat. During and after inflation, the empire became increasingly dependent on foreign credit, particularly US credit. The global economic crisis emanating from the USA hit the German Reich extremely hard, as its economy was more closely interwoven with the US economy than others.

In the Treaty of Rapallo , Walther Rathenau tried to defuse the significant economic consequences caused by the Versailles Treaty and the foreign policy isolation of the German Reich . In it the relationship with the Soviet Union was normalized and mutual claims were waived.

In the first few years of his reign, Hitler was able to reap great domestic political prestige by removing the last constraints of the Versailles Treaty, including military rearmament and reoccupation of the Rhineland . The USA immediately withdrew from European politics; France and Great Britain opted for a policy of appeasement .

The Little Treaty of Versailles

In addition to the Versailles peace treaty explained here, there is another less well-known suburban Paris treaty of the same name. The Polish minority treaty of June 28, 1919 is known as “the little Treaty of Versailles”. This is the first international law treaty with specifically developed protective rights provisions for national minorities .

Text output

- The Versailles Peace Treaty along with the final protocol and the Rhineland Statute as well as the mantle note and German implementing provisions . With a table of contents and subject index, along with an overview map of Germany's current political borders. New revised edition as revised by the London Protocol of August 30, 1924 . Hobbing. Berlin 1925. Digitized version of the University and City Library of Cologne . Public domain.

literature

- Manfred F. Boemeke, Gerald D. Feldman , Elisabeth Glaser (eds.): The Treaty of Versailles. A reassessment after 75 years . Cambridge University Press, New York 1998, ISBN 0-521-62132-1 .

- Eckart Conze : The great illusion. Versailles 1919 and the reorganization of the world. Siedler Verlag, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-8275-0055-7 .

- Wolfgang Elz: Versailles and Weimar. In: APuZ . 50-51 / 2008, pp. 31-38.

- Sebastian Haffner , Gregory Bateson : The Treaty of Versailles . Ullstein Verlag, Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-548-33090-8 (contains the full text of the Versailles Treaty).

- Bruce Kent: The Spoils of War. The Politics, Economics and Diplomacy of Reparations 1918–1932 . Clarendon, Oxford 1989, ISBN 0-19-822738-8 .

- Eberhard Kolb : The Peace of Versailles . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-50875-8 (brief overview).

- Hans-Christof Kraus : Versailles and the consequences. Foreign policy between revisionism and understanding 1919–1933 . be.bra Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-89809-404-7 .

- Gerd Krumeich : The unresolved defeat. The trauma of the First World War and the Weimar Republic. Herder Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 2018, ISBN 978-3-451-39970-1 .

- Gerd Krumeich (Ed.): Versailles 1919. Aims - Effect - Perception . Klartext Verlag, Essen 2001, ISBN 3-88474-945-5 .

- Peter Krüger : Versailles - German foreign policy between revisionism and peacekeeping . Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-423-04513-2 .

- Jörn Leonhard : The overwhelmed peace. Versailles and the world 1918–1923. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-406-72506-7 .

- Margaret MacMillan : The Peace Makers. How the Versailles Treaty changed the world . Propylaea, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-549-07459-6 .

- Marcus M. Payk : The original. On the original document of the Versailles Treaty of 1919 , in: Zeithistorische Forschungen 16 (2019), pp. 342–353.

Web links

- Page on the Treaty of Versailles at the LeMO with many graphics

- Complete text of the contract

- Information on the Versailles Treaty especially for schools on the SwissEduc education server

- SPIEGEL special 1/2004: The unrest of Versailles

- End and beginning of a disaster - The Versailles Treaty - audio feature on Bayern2Radio, radioWissen

Individual evidence

- ^ The Senate and the League of Nations. In: mtholyoke.edu . Retrieved November 13, 2018 (English): "Reservations with Regard to the Treaty" .

- ↑ 100 Years Peace Treaty - The Burden of Versailles. Accessed June 28, 2019 (German).

- ^ Martin Schramm: The picture of Germany in the British press 1912-1919. Berlin 2007, p. 509.

- ↑ Cf. Ulf Morgenstern: “Oh that's nice here!” Walter Schücking's private letters from the Versailles peace delegation in 1919. In: Yearbook for Liberalism Research 30 (2018), pp. 299–335.

- ^ Henning Köhler: November Revolution and France. The French policy on Germany 1918–1919. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1980, p. 310 f.

- ↑ Hagen Schulze : The Eastern State Plan 1919. In: Quarterly books for contemporary history. 18 (1970), pp. 123-163 ( PDF ).

- ^ Christian Gellinek: Philipp Scheidemann. Memory and memory. Waxmann, Münster 2006, ISBN 3-8309-1695-7 , p. 44.

- ^ Michael Kotulla : German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934). Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 584.

- ^ Justus H. Ulbricht (Ed.): Weimar 1919. Chances of a Republic. Böhlau, Köln / Weimar 2009, ISBN 978-3-412-20359-7 , p. 86.

- ^ Stephan G. Bierling: History of American Foreign Policy. From 1917 to the present. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49428-5 , p. 75.

- ^ André Tardieu: La Paix. Paris 1921, p. 308.

- ^ Henning Köhler: November Revolution and France. The French policy on Germany 1918–1919. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1980, pp. 26–31.

- ↑ Klaus Schwabe (Ed.): Sources on the Treaty of Versailles . Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1997, ISBN 3-534-04822-9 , p. 156 f.

- ↑ Bruce Kent: The Spoils of War. The Politics, Economics, and Diplomacy of Reparations 1918–1932. Clarendon, Oxford 1989, pp. 36-40.

- ^ Georg Grote , Hannes Obermair : A Land on the Threshold. South Tyrolean Transformations, 1915-2015 . Peter Lang , Oxford-Bern-New York et al. 2017, ISBN 978-3-0343-2240-9 , pp. XVII-XX .

- ↑ Stefan Reinecke: Essay Consequences of the First World War: One hundred years after Versailles . In: The daily newspaper: taz . May 6, 2019, ISSN 0931-9085 ( taz.de [accessed May 7, 2019]).

- ↑ a b Werner Conze: The Weimar Republic. In: Peter Rassow (ed.): German history at a glance. Stuttgart 1973, ISBN 3-476-00258-6 , p. 645.

- ^ Peter Krüger: The foreign policy of the republic of Weimar. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1985, p. 134 f.

- ^ Helmut Lippelt: On German policy towards Poland 1925/26. In: Hans Rothfeld, Theodor Eschenburg (Hrsg.): Quarterly books for contemporary history . 19th year 1971 / 4th issue / October, Institute for Contemporary History, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart, p. 331 ( PDF; 6 MB ).

- ↑ See the German-Polish Agreement on Citizenship and Option Issues of August 30, 1924 - Vienna Agreement - ( RGBl. 1925 II, p. 33 f.) And the minority protection treaty between the main allied and associated powers and Poland of June 28 1919 ( text on Clio-online / European history portal , accessed on September 8, 2012).

- ^ Helmut Lippelt: On German policy towards Poland 1925/26. In: Hans Rothfeld, Theodor Eschenburg (Hrsg.): Quarterly books for contemporary history . 19th year 1971 / 4th issue / October, Institute for Contemporary History, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart, p. 326 ( PDF; 6 MB ).

- ^ Jens Boysen: The Polish Optanten. An example of the connection between war and the reorganization of international law. In: Bruno Thoss , Hans-Erich Volkmann (ed.): First World War - Second World War. A comparison. War, war experience, war experience in Germany. Schöningh, Paderborn / Wien 2002, ISBN 3-506-79161-3 , pp. 593–614, here: pp. 593, 604–607.

- ↑ Peace Treaty of Versailles, Part V: Provisions on Land Army, Sea Power and Aviation, Chapter III: Army Supplement and Military Training, Articles 173 and 174

- ^ Dan van der Vat: Battlefield Atlantic. ISBN 3-453-04230-1 , p. 82.

- ↑ Articles 42 to 42

- ^ Deutsches Historisches Museum: 1920 , accessed on August 4, 2009.

- ↑ Reich Disarmament Act of August 7, 1920.

- ↑ Disarmament Act in: bundesarchiv.de

- ↑ Gerhard Werle : Völkerstrafrecht , Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2007, p. 4 f., Rn. 5 ff.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German history of society. Volume 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949. 2., through Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 245.

- ↑ Bruce Kent: The Spoils of War. The Politics, Economics and Diplomacy of Reparations 1918–1932 . Clarendon, Oxford 1989, p. 72 f.

- ↑ Peace Treaty of Versailles. June 28, 1919. Chapter III. Article 331

- ↑ Eberhard Kolb : The Peace of Versailles. Beck, Munich 2005, p. 100.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler : Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. CH Beck, Munich 1998, p. 158.

- ^ Gerhard Werle: International Criminal Law . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2007, p. 6 f., Rn. 8–11 ff.

- ^ Christian Hillgruber : How did the Versailles Peace Treaty fail? FRY 2015, pp. 6–12.

- ↑ Bruce Kent: The Spoils of War. The Politics, Economics, and Diplomacy of Reparations 1918–1932. Clarendon, Oxford 1989, p. 79 fuö.

- ↑ Quoted from Henning Köhler : Germany on the way to itself. A story of the century . Hohenheim-Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, p. 161.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society. Volume 4, CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 408.

- ^ Oskar Stillich : The Peace Treaty of Versailles in the mirror of German war aims. Verlag O. Wachsen, Berlin 1921 (a sociological consideration of: methods of combating it, its opponents, its legal character, its material feasibility, its influence on the redesign of the world).

- ^ Michael Salewski : The Weimar revision syndrome. In: From Politics and Contemporary History . 2 (1980), pp. 14-25.

- ↑ It's father's fault . In: Der Spiegel . No. 21/1959 ( online [accessed June 23, 2014]).

- ↑ The Old Testament scholar Otto Procksch said in a speech at the University of Greifswald on January 18, 1924 (“King and Prophet in Israel”) something typical of the mood among the professors at the time: the name Versailles, over which an imperial crown once floated, leaves nothing to be desired clot the blood today. Because from Versailles we only brought the fool's cap home; and we are helpless, defenseless, dishonorable. France itself broke the treaty a year ago, but we are fulfilling, fulfilling, fulfilling. If the German way of life and Christian faith are combined, then we are saved, then we want to work with our hands and wait the day until the German hero comes, he comes as a prophet or king. ( Greifswald University Speeches , Volume 10, p. 22 f.)