Kingdom of Yugoslavia

| Kraljevstvo Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca (1918–1921) Kraljevina Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca (1921–1929) Kraljevina Jugoslavija (1929–1941) |

|||||

| Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes Kingdom of Yugoslavia |

|||||

| 1918-1941 / 45 | |||||

|

|||||

|

Motto : Jedan narod, jedan kralj, jedna država ( Serbo-Croat. For one people, one king, one state ) |

|||||

| Official language |

1918–1929: Serbo-Croato-Slovenian. 1929–1941: Yugoslavian |

||||

| Capital | Belgrade | ||||

| Head of state | King of Yugoslavia | ||||

| Head of government | Prime Minister of Yugoslavia | ||||

| surface | 247,542 km² | ||||

| population | 11,998,000 (1921) | ||||

| Population density | 54 inhabitants per km² | ||||

| currency | 1918–1920 Yugoslav crown from 1920 Yugoslav dinar |

||||

| National anthem | Medley by Bože Pravde , Lijepa naša domovino and Naprej zastava slave | ||||

| Time zone | UTC +1 | ||||

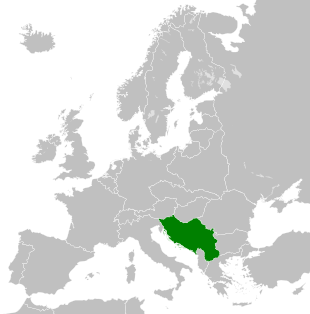

| Location of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in Europe | |||||

| Division of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia into banks | |||||

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( Serbo-Croatian and Slovenian Kraljevina Jugoslavija / Краљевина Југославија), also known as "first Yugoslavia " (South Slavia), was a monarchy from its founding in 1918 until it was occupied by the Axis powers in World War II in 1941 .

The multi-ethnic state in south-eastern Europe comprised the present-day states of Slovenia , Croatia , Bosnia and Herzegovina , Serbia , Montenegro , Kosovo and North Macedonia . The areas south-east of Trieste and Istria , today parts of Slovenia and Croatia, were, however, assigned to Italy . The northern border with Carinthia was not determined by a referendum until 1920 on the border that separates Carinthia and Slovenia today.

From October 29 to December 1, 1918, the state of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs existed for a short time (Serbo-Croatian: Država Slovenaca, Hrvata i Srba , Slovenian: Država Slovencev, Hrvatov in Srbov ). In the same year, through the merger with the Kingdom of Serbia, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (Serbo-Croatian: Kraljevina Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca , Serbian - Cyrillic Краљевина Срба, Хрвата и Словенаца , in Slovene: Kraljevalvina , Slovene: Kraljevalvina ) was created also called SHS Kingdom , State of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes or (like its predecessor) SHS State . After the coup of King Alexander I in 1929, he was given dictatorial powers and, as part of a constitutional reform, the official name of the state was changed to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia .

On March 25, 1941, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia joined the Tripartite Pact under intense pressure . Immediately afterwards a coup took place , which was in turn answered with the German invasion in April 1941. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was occupied by the Axis powers and de facto dissolved ( de jure there was a government in exile in London until 1945 ).

At the end of the Second World War , the "Democratic Federal Yugoslavia" was first founded on the territory of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia on the basis of the AVNOJ resolutions , which was later called the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia .

people

The official name of the South Slavic state was initially the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (1918–1921 Kraljevstvo Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca , since 1921 Kraljevina Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca ).

When the state was founded , people spoke of a nation made up of three peoples: Serbs , Croats and Slovenes . The governments, which were always dominated by Serbia, stuck to this construct, which did not coincide with the attitude towards life of most Croatians and Slovenes, because the state with the “Vidovdan Constitution” was constructed as a unitary state on this basis. Slavic Muslims and Macedonians were not mentioned as relevant parts of the common nation, but officially listed as Muslim Serbs or southern Serbs. Bosniaks were also claimed by the Croats as part of their nation.

In the German-speaking countries, the term South Slavia was also used .

Territorial division

When the state was founded , the national territory finally comprised the following territories:

- the Kingdom of Serbia (with today's North Macedonia and Kosovo )

- the Kingdom of Montenegro, which was recently united with Serbia

- the Austro-Hungarian occupation area of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- the Hungarian crown land Croatia-Slavonia

- the Hungarian Vojvodina

- the Austrian crown land of Dalmatia

- the Austrian crown land of Carniola

- Parts of the Austrian crown lands of Carinthia and Styria populated by southern Slavs

The kingdom was divided into:

- 1918–1921: 7 provinces ( pokrajine ) based on the original historical units

- 1921–1929: 33 areas ( oblasti )

- 1929–1939: 9 banks ( banovine )

- 1939–1941: 7 banks and the autonomous bank of Croatia ( Banovina Hrvatska )

Banks The banks of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and its capitals were in 1929–1941:

- Dravska banovina (Banschaft Drava): Ljubljana

-

Banovina Hrvatska (Banschaft Croatia): Zagreb (1939 amalgamation of two banks through the Cvetković - Maček contract ( Sporazum Cvetković – Maček, Serbian-Croatian settlement ))

- Savska banovina (Bank of Save): Zagreb

- Primorska banovina (Banschaft Coast): Split

- Vrbaska banovina (Banschaft Vrbas): Banja Luka

- Drinska banovina (Banschaft Drina): Sarajevo

- Zetska banovina (Banschaft Zeta): Cetinje

- Dunavska banovina (Danube Bank ): Novi Sad

- Moravska banovina (Banschaft Morava): Niš

- Vardarska banovina (Banschaft Vardar): Skopje

population

languages

According to the doctrine of the one Yugoslav nation, the government pursued a rigorous language policy aimed at aligning the other South Slav language variants with Serbian. It was easiest for the Slovenes to evade this requirement, since they had long had a written language that was clearly different from Serbo-Croatian . The Croatians had less good arguments, because apart from the different scripts that were both allowed, the Croatian differed little from the standard Serbian language. The arguments on detailed issues were all the harder. In Macedonia , where dialects similar to Bulgarian were spoken but no written language of their own existed, the authorities continued the Serbization that began in 1913.

Religions

The Serbs , Macedonians and Montenegrins were predominantly Orthodox (approx. 47%); the Croatians and Slovenes almost all belonged to the Roman Catholic Church (together with other nationalities approx. 39%). About 11 percent of the population ( Bosniaks , Albanians and Turks ) were Muslims . There were some Protestants (around two percent) among the German and Hungarian minorities . There was a Jewish minority (approx. 0.5%).

Of particular political importance was the relationship between the Serbian Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches and the state. In this respect, too, the SHS state assumed an extremely heterogeneous legacy when it was founded:

Apart from the largely marginalized Muslim minorities, Serbia and Montenegro were purely Orthodox countries and Orthodox Christianity was, as it were, the state religion there. In 1920 the Orthodox dioceses in central Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia, Slavonia, Dalmatia and Vojvodina united to form the Serbian Orthodox Church. At the same time, the Serbian patriarchate was renewed. In this regard, the Orthodox Church in Serbia had achieved its goals. However, through the merger of Serbia with large Roman Catholic areas, it lost the character of a state church . The unity of church and state, as practiced in the orthodox neighboring countries Greece and Bulgaria , was not possible in Yugoslavia and also not wanted by the government.

Religious pluralism prevailed in the Habsburg monarchy, but Roman Catholics were in the vast majority almost everywhere, including Croatia and Slovenia, and the Roman Catholic Church was a very influential force in society. The Catholicism had almost been regarded as one of the main pillars of the Habsburg Empire, although the relationship with the government had not always been untroubled and even priests and bishops had been involved in the national movement. In Slovenia, the Katoliška narodna stranka , in which Roman Catholic priests were also involved, was by far the strongest party until 1941. In Croatia, too, the church was firmly anchored in the Roman Catholic milieu, but it had less direct influence on the political parties. In any case, the Roman Catholic Church also had to adjust to a new situation. After 1918 it was only one of the two strong religious communities. The Croatian bishops only commented on nationally controversial politics after national parties, including those of the Croatians, had been banned.

There was hardly any contact between the two large churches. The state acted secularly and left the regulations on the state-church relationship largely untouched. This also applied to the Muslims in Bosnia. The Muslims in Yugoslavia initially had two higher authorities, one in Sarajevo and one in Skopje. That of Skopje was later subordinated to that of Sarajevo. The Muslims in southern Serbia (Kosovo and Macedonia) had no contracts with the state. Some of their foundations were expropriated in order to settle Serbian colonists in the countryside. Direct conflicts with the Christian churches were rare.

In accordance with the papal policy according to the Lateran Treaty , the Roman Catholic bishops endeavored in the 1930s to conclude a state church treaty and the Yugoslav government was also very interested in it for two reasons: On the one hand, it was hoped that the Croatian bishops would then express their opinion of their faithful to the government would positively influence, on the other hand, the contract with the Pope would have been a foreign policy success against Italy.

When the Concordat was signed in 1937, a storm of indignation broke out among the Orthodox Serbs. Under the leadership of the Ohrid Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović there were mass protests against the treaty with Rome. The Serbs accused the government of selling out Orthodox interests. For fear of increasing resistance, the government did not have the concordat ratified in parliament. That in turn snubbed the Roman Catholic Croats and Slovenes. As a result of the Concordat dispute, the previously very cool Orthodox-Catholic relationship in Yugoslavia was charged with national politics.

Position of the Serbs

The Serbs (including the Montenegrins) were the numerically largest group, with just over 40 percent of the total population of Yugoslavia. The Serbs were disproportionately represented in all parts of the state administration, as they had brought their own bureaucracy into the new state. In the southern Serbian areas of Kosovo and Macedonia, there was a narrow layer of Serbian civil servants who ruled over the non-speaking population, which was, not least, often hostile to the state apparatus. After the collapse of the Danube Monarchy, all non-Slavic civil servants in the areas that were now part of the SHS state lost their posts and many of them left the country. (These former k. U. K. Civil servants made up the majority of the non-Slavic emigrants. The German and Hungarian populations were not forced to emigrate.) The vacant positions in Bosnia, southern Dalmatia and parts of Slavonia were mainly filled with civil servants from central Serbia. The position of the Serbs in the military was particularly dominant, where they held three quarters of the officer positions.

Serbian-Croatian equalization

In 1939 the Croats got their own administrative unit, the Croatian Banschaft with extensive rights of self-determination in domestic political and economic competencies. Yugoslavia now consisted of seven Yugoslav and one Croatian banks.

The Serbian-Croatian settlement did not have the desired effect for either party. For many Croatians, the autonomy did not go far enough; In particular, they accused Maček of having betrayed Croatia's national cause by surrendering Bosnia, which for the most part did not belong to the Croatian bank. The centralist Serbs also accused the government of betraying their national interests. Due to the Second World War, many of the new regulations were practically no longer implemented.

education

Like the other development indicators, the educational level of the Yugoslavs also showed an extreme north-south divide.

In Serbia

In central Serbia there was a comprehensive network of primary schools, but there was a lack of secondary schools. In the areas added in 1912, the school system left most to be desired. There were not enough primary schools at all and the minority languages were not taken into account in the existing ones. Since the Muslim Albanians also had no religious schools, there were almost no Albanian-language educational institutions. Accordingly, the illiteracy rate was highest in the southern areas. Here about. two thirds of the population do not read or write. Vojvodina took a better place in the development of the school system. Here, in addition to the state, the churches (in addition to the Roman Catholic and Serbian Orthodox also the Protestant) maintained many schools. The minority languages German and Hungarian were only taught in private schools.

In Croatia

In Croatia, even more than in Slovenia, the school system was a church affair. Although the school network has also been consolidated here, the gap to Slovenia has not narrowed. In inland Croatia the illiteracy rate was over 15%, in parts of Dalmatia it was over 25%.

In Bosnia

In Bosnia the level of education differed extremely according to religious affiliation. It was highest among the Croatians, who had access to a school system developed by the Roman Catholic Church during the Austrian period, followed by the Serbs, while the Muslims brought up the rear, mainly because the vast majority of Muslim girls were not sent to school at all has been.

In Slovenia

Slovenia already had a well-developed school system in 1918. Over 90 percent of the children attended a state or church primary school. The illiteracy rate was below ten percent. After the war, middle school education (secondary schools and grammar schools) was improved for the Slovenes, on the one hand, because German-speaking schools in Carniola and Styria had switched to the Slovenian language of instruction, and on the other hand, there were also numerous start-ups, some of which were run by the Catholic Church were borne by the state.

Universities

In 1918 there were two universities in Yugoslavia: in Belgrade and in Zagreb. Immediately after the end of the war, the Slovenes founded the country's third university in Ljubljana in 1919. This made a long-cherished wish of Slovenian intellectuals come true. Under Austrian rule, they had been denied the opportunity to set up their own university for decades.

School funding

The Yugoslav state lacked both the financial means and the political will to raise the low level of education, especially in the southern regions. There was no interest at all in promoting the Albanians. These in turn stayed away from the existing Serbian schools because they were seen as an instrument of Serbization.

There was progress in the interwar period, especially in Croatia and Serbia. In Croatia, the Yugoslav state founded secular schools in order to somewhat diminish the dominance of the Roman Catholic Church in education. Overall, however, the state remained dependent on the cooperation of the churches. The SHS state has also not been able to decide to introduce compulsory schooling. This meant a step backwards for the formerly Austrian areas, because before 1918 there had been compulsory education there for eight years.

history

| Chronology 1917–1941 | |

|---|---|

| 07/20/1917 | Declaration of Corfu |

| December 01, 1918 | Proclamation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in the Krsmanović House |

| 11/12/1920 | Rapallo border treaty with Italy |

| 06/28/1921 | Adoption of the Vidovdan -Constitution |

| June 1928 | Stjepan Radić was assassinated in Skupština |

| 01/06/1929 | Establishment of the royal dictatorship |

| 10/03/1929 | Renaming of the SHS state to "Yugoslavia" |

| 09/03/1931 | new constitution issued by the king, continued centralized state structure and Serbian domination |

| 10/09/1934 | King Alexander is assassinated by an IMRO terrorist in Marseille |

| 1939 | Agreement between the Croatian Peasant Party and the government, partial autonomy of Croatia |

| 03/25/1941 | Prince Paul signed the accession to the Tripartite Pact , but the military successfully staged a coup on March 27. |

| 04/06/1941 | Germany invaded Yugoslavia |

| 04/17/1941 | Surrender of the Yugoslav army |

Founding of the state

The development of the common state of the Southern Slavs began with the end of the First World War and the break-up of Austria-Hungary . The South Slav peoples of the monarchy declared their independence. The first head of state was King Peter I , previously King of the Serbs.

The main representatives of the Croatians and Slovenes initially strove to form their own states. After the end of the war, the strong expansion of Italian imperialism (see Italian irredentism ) induced the representatives of both peoples to agree to the unification of all South Slav peoples under one roof. The Treaty of Trianon in 1920 sealed the secessions from the Kingdom of Hungary that took place in 1918/19 . Montenegro , which had been converted into a kingdom in 1910 , had already united with Serbia on November 29, 1918 after the deposition of King Nikola .

Border disputes

Since the borders of the territories of Austria-Hungary did not run along ethnic borders, the northern border of the new state in particular remained controversial. Gorizia, Istria and some coastal areas had already been promised to Italy as spoils of war or as a reward for changing sides in the Treaty of London and were definitely given in the Treaty of Saint-Germain . In November 1920, the SHS state accepted this limit in the Rapallo Border Treaty , a bilateral agreement.

The border between Austria and the SHS state became a bone of contention for the local population in Southern Carinthia and Lower Styria. Until the Treaty of Saint-Germain, the army of the SHS state tried to create a fait accompli by military occupation of the country. The German-speaking population, however, sought to stay with German-Austria , in the hope of the self-determination of the peoples announced by US President Woodrow Wilson . In Lower Styria there were attacks on the civilian population and isolated expulsions, for example on Blood Sunday in Marburg , but no organized military confrontation. It is different in Carinthia, where the Carinthian defensive battle was carried out in 1918/19 and the final border was only fixed by referendum in 1920.

Nationalist tensions

From the beginning, the political situation of the new state was shaped by the escalating conflict between the centralistically minded Serbian parties and the federalistically minded Croatian parties. While Croatian parties were striving for a dualistic state consisting of Serbia and Croatia, Serbian parties defended the unitary state, which they enforced with the Vidovdan constitution of June 28, 1921 despite boycotts by the Croatian and Slovenian delegations: a strongly centralized government, historical national borders repealed and the state divided into 33 areas.

While Croatian parties then usually boycotted or disrupted the parliamentary sessions, the Slovenes found themselves between the fronts because, on the one hand, they themselves strived for a federalist settlement and, on the other hand, could not find a settlement with the Croatian parties. A slogan that emerged in Slovenia at the time was: “The Serbs rule, the Croats argue, and we Slovenes pay extra.” After the establishment of the SHS state, Croatian national consciousness experienced a great boom and was directed against the new kingdom, or more precisely in other words, against the supremacy that the Serbs claimed for themselves.

Royal dictatorship from 1929

All of this paralyzed state affairs and led to permanent minority governments , all of which consisted of Serbian parties. The failure of a general settlement finally led to the state crisis of 1928/1929: After 40 short-lived governments in eleven months of 1927/28 (average term of office of the governments two weeks), and growing domestic political unrest, which resulted in the assassination of the leader of the most important Croatian party Stjepan Radić culminated, King Alexander Karađorđević decided on January 6, 1929 with the help of the army to take power. He suspended the constitution, dissolved parliament and took over the country's affairs of state.

This royal dictatorship , the first in Southeast Europe, was supposed to create peace and order. In the new constitution introduced on October 3, 1929, the state was renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( Kraljevina Jugoslavija ). A new administrative structure consisting of nine banks was introduced, the boundaries of which were deliberately drawn away from the historically grown units. The failed parliamentarism was abolished, the parliament dissolved, the parties banned. The king became the sole bearer of state power .

Alexander and the government established by him under General Petar Živković (1879–1953), previously commander of the royal palace guard, now tried other means to unite the state that was renamed "Yugoslavia". The administration was reformed. The borders of the banks were drawn in such a way that in six of the banks the Serbs had the majority of the population, while only two banks were predominantly Croatian. The Croatian opposition in particular interpreted the new administrative structure as a sign that the king, too, was betting on the unification of the country under Serbian leadership. But even the royal dictatorship was unable to solve the problems of Yugoslavia, which were exacerbated by the global economic crisis .

The next sensational murder occurred in February 1931: the Croatian scientist and parliamentarian Milan Šufflay was murdered on the street in Zagreb. Since the investigation was slow and the crime was ultimately not resolved (according to some opinions, the investigation was even hindered), the suspicion soon arose that the Yugoslav secret police were behind the attack.

Assassination attempt on the king

In 1931 government and parliamentary elections were reintroduced, but government and parliament were limited by the position of the monarch. Furthermore, national parties and symbols of the individual peoples were banned, only all-Yugoslav parties were allowed. While these measures resulted in permanent governments, these governments were not representative of the entire nation. Ideologically, these measures were attempted to consolidate the three-name nation theory (a Yugoslav nation under the three names of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, a Yugoslav people with the "tribes" of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, etc.), the Serbian and Croatian Language summarized to the Serbo-Croatian language. On the outside, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia seemed to be stabilizing, but on the inside the differences between the individual peoples increased. The Croatians in particular perceived the new political order as Serbian domination. While Croatian and Macedonian nationalists viewed Yugoslavia as a Greater Serbian hegemony and tried to fight it partly with terrorist means, the representatives of another Yugoslavia, the Yugoslav communists , spoke of a monarcho-fascist dictatorship .

King Alexander I fell victim to an attack planned by Croatian right-wing Ustashas and the Bulgarian IMRO (and possibly other secret services) in 1934 in Marseille . Because of consideration for fascist Italy , which supported the Ustasha, France showed itself to be uncooperative in the investigation of the attack. Numerous conspiracy theories about the attitude of France, up to then the closest ally of Yugoslavia, emerged. This led to a rapprochement between Yugoslavia and National Socialist Germany under Prince Regent Paul , a cousin of the murdered king.

Return to parliamentarism

The German economic policy, which tried to bind the Balkan and Danube countries (“supply area” of the “Greater German Reich”) by means of material and technical remuneration and aid, also had an effect in Yugoslavia. Over 50% of all imports and exports were made with Germany. Yugoslavia became more and more dependent on Germany. The Prime Minister Milan Stojadinović tried to loosen Yugoslavia's economic dependence on Germany without much success with the policy of rapprochement with Italy recommended by the French Prime Minister Pierre Laval .

At the end of the 1930s, Prime Minister Stojadinović recognized the difficult foreign policy situation in Yugoslavia and tried to overcome the country's isolation by moving closer to the Axis powers. His goal was neutrality in the expected next great war. Domestically, too, he orientated himself towards Germany and Italy. He let himself be called a leader and created a uniformed youth organization. In February 1939, however, Stojadinović was voted out of office as prime minister.

In 1939, with the mediation of Germany and Italy, the last constitutional amendment and thus reorganization of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia came about. The kingdom increasingly returned to the parliamentary form of government, but King Alexander's 1929 constitution remained in force. Prince Paul retained decisive influence.

Second World War

Under Stojadinović's successor, Dragiša Cvetković , an agreement between the Croatians and the government was reached. In the so-called Sporazum (German: Agreement ) of August 26, 1939, which Vladimir Maček had negotiated for the Peasant Party with Cvetković, the creation of a largely autonomous Banschaft Croatia was planned. Belgrade's approval of this treaty was largely due to the dangerous foreign policy situation. It was known that some Croatian politicians sought contact with the governments in Rome and Berlin in order to reinforce their demands. The invasion of the Wehrmacht into the rest of Czechoslovakia and the establishment of the Slovak Republic had also worried the Yugoslav government.

After Germany's victory over France, Yugoslavia came under increasing diplomatic pressure. Adolf Hitler demanded that the country join the Pact of the Axis Powers . On March 25, 1941, the Yugoslav government gave in and signed. In response, officers who wanted to get Yugoslavia on the side of the Allies carried out a successful coup in Belgrade. They declared the young Peter II reigning king and put General Dušan Simović at the head of the government. The enthusiasm for war, which briefly flared up in Belgrade, did not even last until the actual outbreak of war. The population quickly realized that the Yugoslav army had no chance against the German armed forces . Many Croatians, Slovenes and Muslims did not even obey the draft order.

The German invasion began on April 6, 1941 , and on April 17 the Yugoslavs signed the unconditional surrender. The king and government went into exile in England, from which they were not to return.

End of the kingdom

After the war, King Peter II issued the pro forma government mandate to Josip Broz Tito from exile . This was done under pressure from the Allies to give legitimacy to the new communist Yugoslavia . In November 1945 the young king finally abdicated and handed over the supreme power of the state to the imperial administrators Srđan Budisavljević , Ante Mandić and Dušan Sernec . As early as December 1945, the new communist ruler Tito had Yugoslavia proclaimed a Federal People's Republic .

politics

Domestic politics

The domestic political situation was essentially determined by the nationality conflicts. The conflict between the predominantly autonomist Croats and the centralist forces on the Serbs dominated. However, this was not the only source of conflict. Many Slovenes, some of the Bosnian Muslims as well as the Macedonian Slavs, were not satisfied with the Unitarian view of the one Yugoslav (South) Slavic nation. And finally, the members of the German and Hungarian minorities felt themselves to be second-class citizens. The Albanians in Kosovo were treated particularly badly by the government.

Constitution

The 1921 Vidovdan constitution provided for a bicameral parliament . In addition to the National Assembly , the Senate acted as the House of Lords. After the Vidovda Constitution was passed in 1921, the members of the Croatian Peasant Party stayed away from parliament for years and Nikola Pašić ruled the country at the head of changing coalitions. To maintain power, he also used the means of political trials. His fiercest political opponent Stjepan Radić was also briefly detained for activities that were dangerous to the state. Nevertheless, Radić joined Pašić's government in 1925 after a coalition with the Slovenes and Muslims had failed. In 1926 Pašić had to resign because of his son's corruption affair. After new elections, Svetozar Pribičević ( Democratic Party ) and Radićs Peasant Party formed a coalition in 1927. But that did not lead to more political stability either.

In June 1928, Puniša Račić , a Montenegrin member of the Radical Party, shot three Croatian MPs in the Belgrade Parliament, including Stjepan Radić, who died of his injuries on August 8, 1928 . After this act of violence, the political situation became completely chaotic, which ultimately led to the coup and the reorganization of the state under King Alexander I.

Party system

The party system of the first Yugoslavia was largely divided along ethnic and cultural lines. In Serbia, the conservative and centralist Serbian-oriented Radical People's Party ( Narodna radikalna stranka ) of long-time Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić dominated for a long time . The other major party was the socially and Yugoslav oriented Democratic Party ( Demokratska Stranka ). She was strong in Vojvodina and was chosen by non-Serbs in other parts of the country. The communists, who also appeared in all Yugoslavia, were banned in 1921. In Croatia, the federal-republican Croatian Farmers' Party Stjepan Radićs dominated . In addition, the Croatian Right Party ( Hrvatska stranka prava ) was important, from which the Ustasha movement later emerged. The Roman Catholic Slovenian People's Party under Anton Korošec was the leader among the Slovenes . Unlike the Croatian parties, the People's Party did not remain in fundamental opposition, but tried to enforce the interests of the Slovenes through parliamentary channels. Finally, the Yugoslav Muslim Organization (JMO) should be mentioned, which had the most supporters among the Slav Muslims in Bosnia and in Sandžak , but was also elected by Albanians.

The main political parties were:

- Agrarian Association

- Democratic Party

- German party

- Džemijet (Party of Muslims mainly in Kosovo and Macedonia)

- Yugoslav Muslim Organization (Jugoslovenska muslimanska organizacija, JMO)

- Communist Party

- Croatian Peasant Party

- Radical People's Party (Chairman: Nikola Pašić )

- Slovenian People's Party (Slovenska ljudska stranka, SLS)

- Social Democratic Party (Chairman: Živko Topalović )

Minority policy

According to Johann Böhm , there was no minority protection under the royal dictatorship of Yugoslavia, although at least the German ethnic group was loyal to the king. The minority protection treaty that Yugoslavia concluded with the Entente powers on December 5, 1919 with regard to the treatment of ethnic minorities contained a number of provisions which were expressly referred to as the Basic Law ("lois fondamentales") and which amounted to the protection of ethnic minorities to grant. However, Belgrade disregarded these provisions on the grounds that the protection of minorities would add confusion to state life. In September 1922, the magazine “Zastava” asked the question about minorities: “Citizens or troublemakers?” Belgrade saw the minority protection conventions as enforced provisions on the part of the authority of the peace conference. The right of assembly of the minorities was not respected, the school system of the national minorities should be destroyed by repeated ordinances of the Ministry of Education. The German and Hungarian minorities were excluded from the Yugoslav agrarian reform. The expropriated land was redistributed to Serbs from old Serbia, so-called "Dobrowolz".

The Albanians resolutely rejected the Yugoslav state. Serbian nationalists perceived their hostile attitude as a threat to the national project, especially since the Serbian colonization of Kosovo, which was aimed at after the First World War, had proven to be a failure. In 1937 Vaso Čubrilović worked out a plan for the resettlement and expulsion of the Albanians. The following year, an agreement was signed with Turkey that provided for the relocation of 40,000 Muslim families from Kosovo and Macedonia to Turkey. The outbreak of World War II and the break-up of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia pre- empted a possible implementation of this agreement.

Conflicts

The old big parties of the Slovenes, Croats and Muslims demanded the democratization and federalization of the state in programmatic resolutions of 1932/1933 (punctuations from Zagreb, Ljubljana and Sarajevo) . Thereupon the party leaderships were interned. At the same time, the Ustaše and IMRO are intensifying their terrorist actions aimed at breaking up the Yugoslav state. A Ustasha uprising in 1932 can easily be put down by the police due to the lack of participation. The joint terrorist attacks by IMRO and Ustasha reached their climax on October 9, 1934 with the murder of King Alexander in Marseille . But contrary to what Ante Pavelić thought, the government was able to cope with this crisis.

Prince Paul, the brother of the murdered king, took over the reign of his underage son Peter II. With the consent of the regent, a new pro-government unity party, the Jugoslavenska radikalna zejednica, was formed, which also won the elections in 1935 and was Prime Minister with Milan Stojadinović .

The attempt to implement an integral Yugoslavism from above was dashed by the tensions between the political representatives of the various national and religious groups. So the Yugoslav state remained a multi-ethnic state. In particular, the relationship between Serbs and Croats was full of conflict.

Foreign policy

Yugoslav foreign policy in the interwar period was characterized on the one hand by the endeavor to neutralize the revision efforts of the former war opponents Hungary and Bulgaria, on the other hand by the latent conflict with fascist Italy, which had appropriated Slovenian and Croatian populated areas in the former Austrian coastal region and in Dalmatia and continued to claim to Yugoslav Dalmatia and Albania ("the Adriatic as an Italian inland sea").

On the eve of World War II , Yugoslavia was isolated in terms of foreign policy. After the Western powers had already surrendered parts of Czechoslovakia to the German Reich and had not given Poland any effective support in 1939 , Yugoslavia was helplessly at the mercy of the Axis powers.

Allies

When the traditional main ally of Serbia, Russia, was canceled by the October Revolution , France took its place. In the interwar period, Yugoslavia was an important member of the alliance system in Eastern Europe, which was supported by France. From 1920 to 1939 the country was linked to Czechoslovakia and Romania in the Little Entente . This alliance was primarily directed against Hungary. When Germany expanded its influence to Central and Southeastern Europe, this union became obsolete. The break-up of Czechoslovakia deprived the Little Entente of its livelihood.

Bulgaria

Relations with neighboring Bulgaria were poor throughout the interwar period because of the Macedonia issue. Bulgaria did not recognize the rule of Yugoslavia over Vardar Macedonia . Just as Yugoslavia claimed the Slavic Macedonians for themselves as southern Serbs, Sofia saw them as oppressed Bulgarians and supported the terrorist organization IMRO , which was committed to the liberation of Macedonia. The Yugoslavs built extensive border protection systems on the Bulgarian border. Nevertheless, IMRO people repeatedly managed to break into Yugoslavia from their retreat areas in Bulgaria. In 1934 Yugoslavia concluded the Balkan Pact against Bulgaria with Greece and Turkey . Like the Little Entente, this alliance did not achieve any practical effect either.

Italy

Yugoslavia was also unable to achieve good neighborly relations with Italy . On November 12, 1920, the two powers signed the Rapallo Border Treaty , albeit without both sides giving up any further territorial claims. Italy was confirmed in possession of Istria and received some Dalmatian islands as well as Zadar (ital. Zara ) on the mainland, but waived the claims to Split (ital. Spalato ) and its surroundings. Rijeka (Italian: Fiume ) was declared the Free State of Fiume . This rule lasted less than four years. The Italian fascist Gabriele D'Annunzio took power in the city in 1924, triggering another crisis in Yugoslav-Italian relations. In the Treaty of Rome , the area of the Free City of Fiume was divided between the two powers. The closer cooperation between Yugoslavia and Italy, which was actually established in Rome, never materialized. The further relationship between the two states was marked by confrontation. So Benito Mussolini supported the fascist Ustasha from 1929 to 1934 in order to destabilize the enemy Yugoslavia in this way. The oppression of the Slavic minorities in the areas that fell to Italy led to many Slovenes and Croats in those regions joining the Tito partisans during the Second World War.

Albania

Because of the insecure situation in Kosovo - an uprising against the renewed Serbian rule broke out there after the First World War - Yugoslavia interfered in Albania , where Albanians in exile from Yugoslavia were represented in the government. In Tirana they demanded the military and political support of their compatriots, although the weak Albania was not in a position to do so. In addition, the Albanian government sought to align with Italy. In order to calm down on this border and prevent Italian influence in Albania, the Pašić government supported Ahmet Zogu with troops in 1924 . Zogu put himself to power in Tirana, but continued to orientate himself in foreign policy towards his most important trading partner Italy.

economy

After the borders of Yugoslavia were drawn in 1919/20, the country had to be united into an economic and currency area. In the former Habsburg areas the crown was valid, in Serbia the dinar . The government had to reduce the money supply to fight inflation caused by the war . The creation of the new single currency, also known as the dinar , took place in 1920. According to plans by the then President of the National Bank, the German Georg Weifert , the Serbian dinar was exchanged 1: 1, but the krona at a ratio of 4: 1. This caused great bitterness in Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Vojvodina, as the former Danube Monarchy Slavs lost 75% of their wealth and thus paid for the creation of the new currency, while the inhabitants of old Serbia did not have to contribute.

The SHS state in the interwar period was a poorly developed agricultural state. 75% of the working population practiced smallholder subsistence farming . There were productive medium-sized and large companies mainly in Vojvodina, in Slavonia and in the north of central Serbia. In Vojvodina in particular, many of these farms were owned by members of the German and Hungarian minorities. The Roman Catholic Church was one of the major landowners in the developed areas that had previously belonged to the Danube Monarchy. Slovenian agriculture was also comparatively well developed. The factories in the northern regions mentioned had sold their surpluses to the industrial regions of the Habsburg monarchy before the war. Some of it was previously processed in the local food industry (mills, sugar factories, etc.). Due to the new borders (tariffs) and the declining purchasing power in Austria, these markets were largely closed to the Yugoslav farmers in the interwar period. Since the mid-1930s, National Socialist Germany began importing food from Yugoslavia in the course of war preparations.

In the southern parts of the country (in Macedonia, in the south of central Serbia and in Kosovo, in Montenegro, Bosnia and Dalmatia) there were almost exclusively small-scale subsistence economies that had little development opportunities. The large landowners in these regions lacked the capital and technical means to modernize their businesses. Because of the abundance of cheap labor and the lack of market prospects, they had little interest in change.

There was notable commercial production in Slovenia, in the Belgrade region and increasingly in Zagreb. Industrial products (e.g. machines and locomotives) had to be imported for the most part, but there was a lack of capital for them. The country's infrastructure could hardly be further developed in the inter-war period. Only a few dozen kilometers of new railway lines were built, and the road network remained almost the same as it was before the First World War.

The extraction of raw materials was important. Various ores (iron, copper, etc.) and coal were mined in Serbia, Bosnia and Slovenia. But there was a lack of factories for further processing. The wood industry was also important. The latter was particularly well developed in Bosnia, where a relatively large amount of investment had been made before the First World War. The problem of bringing raw materials to the world market at competitive transport costs was partially resolved when a treaty was signed with Greece in 1929, which gave Yugoslavia a 70-year free port in Thessaloniki . Communist Yugoslavia later also used this treaty.

shipping

Since important port cities such as Trieste and Rijeka belonged to Italy, Yugoslavia built a new port and shipping location in Sušak , a little south of Rijeka. The shipping company Jadranska Plovidba was founded there. Several former Austro-Hungarian shipping companies joined her: the Dalmatia , the Ungaro-Croata , the Croatian steamship company , the Austro-Croata and several smaller shipping companies. In the years that followed, the fleet was expanded to around 60 ships with a total tonnage of 23,400 GRT - that is, smaller ships throughout, suitable for coastal shipping.

Dubrovačka Parobrodska , which was based in Dubrovnik , soon rose to become the second largest shipping company . This company had only 22 ships - but with a total tonnage of 75,000 GRT.

See also

literature

- Ljubodrag Dimić: Serbia and Yugoslavia (1918–1941) . In: Österreichische Osthefte, 2005, Volume 47, Issues 1–4, pp. 231–264.

- Alex N. Dragnich: Serbia, Nikola Pašić, and Yugoslavia. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick 1974, ISBN 978-0-8135-0773-6 .

- Alex N. Dragnich: The First Yugoslavia. Search for a Viable Political System. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford 1983, ISBN 978-0-8179-7841-9 .

- Jacob B. Hoptner: Yugoslavia in Crisis, 1934–1941. Columbia University Press, New York 1962.

- Sabrina P. Ramet: The Three Yugoslavias. State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2004. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Woodrow Wilson Center Press, Washington D. C. 2006, ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8 .

- Günter Reichert: The failure of the Little Entente. Fides, Munich 1971.

Web links

- Corfu declaration (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Marie-Janine Calic : History of Yugoslavia in the 20th century. C. H. Beck, Munich 2010, p. 87.

- ↑ Jessica von Felbert: Conflict Management in Southeast Europe. Münster 2011, p. 11 ( dissertation at the Westphalian Wilhelms University ).

- ↑ See Ramet: The Three Yugoslavias. (see above), p. 81 and map ibid. p. xxiii.

- ↑ a b c Detlef Brandes; Holm Sundhaussen; Stefan Troebst: Lexicon of expulsions: Deportation, forced resettlement and ethnic cleansing in Europe in the 20th century . Böhlau Verlag, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2010, ISBN 978-3-205-78407-4 , p. 320 f .

- ↑ Ivo Pilar : The South Slav Question and the World War . 1918.

- ^ Mirjana Gross: On the integration of the Croatian nation. A case study in nation-building. East European Quarterly, 15 (1981), No. 2 (June), pp. 209-225.

- ↑ See Holm Sundhaussen , Geschichte Yugoslaviens 1918–1980 , 1982, ISBN 3-17-007289-7 ; Article Stranke političke in: Enciklopedija Jugoslavije , 1st edition, vol. 8.

- ^ Johann Böhm, The German Ethnic Group in Yugoslavia 1918 - 1941 , Peter Lang GmbH Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften, ISBN 978-3-631-59557-2 , page 131ff.

- ↑ Luciano Monzali: La Jugoslavia e l'assetto dell'Europa centrale nella politica estera dell'Italia fascista (1922-1939) . In: Maddalena Guiotto, Wolfgang Wohnout (ed.): Italy and Austria in Central Europe of the Interwar Period / Italia e Austria nella Mitteleuropa tra le due guerre mondiali . Böhlau, Vienna 2018, ISBN 978-3-205-20269-1 , p. 147-159 .