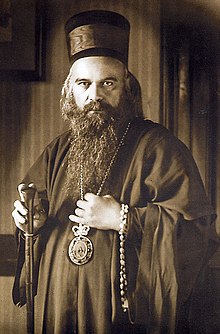

Nikolaj Velimirović

Nikolaj ( Serbian - Cyrillic Николај , civic Nikola Velimirović / Никола Велимировић * December 23, 1880 . Jul / 4. January 1881 greg. In Lelić in Valjevo , Principality of Serbia , Ottoman Empire , † 18 March 1956 in South Canaan , Pennsylvania , United States ) was the Serbian Orthodox Bishop of Žiča (1919-1921 and again from 1934) and also Ohrid (1921-1934). The controversial clergyman was canonized on May 19, 2003 by the Serbian Orthodox Church .

Nikolaj is considered to be one of the founders of the political ideology of the Serbian “ nationalism of St. Sava ”. Velimirović praised Adolf Hitler in his pamphlet of the same name (1935) , compared him with Saint Sava in terms of its importance and praised his efforts to create a “ German national church ”. Velimirović is considered to be one of the inspirers of the Serbian fascist Zbor party , which collaborated with Nazi Germany in Serbia during World War II , and was a personal friend of party leader and fascist leader Dimitrije Ljotić . Nikolaj is often criticized for his anti-Semitic positions.

One of the central points in Nikolaj's world of thought is the criticism of humanism , European civilization, the materialistic spirit and the like. in Europe , which he described as a great evil. He was deeply impressed by Serbia's medieval history at the time of the Nemanjid dynasty, which he believed would become the paradigm of the Serbian present.

Life

Nikolaj was born as Nikola Velimirović in the small Serbian village of Lelić near Valjevo in 1881. He grew up in a devout family. Velimirović participated in church life at an early age and allegedly decided to become a monk at the age of eleven. He attended the priestly school in Belgrade , where he was noticed even then for his eloquence. Until 1908 he studied at the Old Catholic Faculty of the University of Bern , where he obtained a doctorate in philosophy . Velimirović then studied at Oxford and obtained another doctorate. In England he developed a deep friendship with the Anglican Church , which he would later cultivate. Velimirović was also the first non- Anglican to preach in St Paul's Cathedral . In 1909 he returned to Belgrade and became a monk.

In order to curb the strong non-Orthodox influence on Velimirović, the then Archbishop of Belgrade and later Patriarch Dimitrije Pavlović sent him to study at the Orthodox Faculty of the University of Saint Petersburg in Russia . In 1911 Velimirović was appointed as a supplent (assistant teacher) at the Theological Seminary School in Belgrade. During the two Balkan wars 1912-13 he worked as a pastor and helped the sick, poor and suffering.

For diplomatic reasons, the Serbian government then sent him to the USA in 1915 , where he defended the Serbian and Yugoslav cause together with Nikola Tesla and Mihajlo Pupin during the First World War . In 1919 Nikolaj Velimirović was finally appointed Orthodox bishop. In the same year he created the “ Bogomoljci ” (praying mantis) movement, a spiritual movement of pious lay people from the common people. In the 1930s, at the height of his preaching career, Velimirović emerged as the main character and voice of Orthodoxy in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia .

Velimirović was an advocate of a society that should be based on Christian Orthodox traditions and a monarchy . In response to the increasing spread of fascist and right-wing national ideas in Europe in the interwar period, Nikolaj Velimirović founded what is known as “ Christian nationalism ”, which he wanted to oppose to “ethnic nationalism”. In his Christian nationalism, Velimirović called for a return to Christian values, which he regarded as the national and cultural foundation of the Serbs in particular . With this kind of patriotism, Velimirović tried to go beyond national differences. The focus was on the commitment to the monarchy as a God-pleasing political order. Velimirović denounced fascism , communism and right- wing nationalism as well as the uncritical adoption of foreign fads as secular nonsense.

Nikolaj Velimirović and the Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church Gavrilo Dožić, who were considered to be the most influential representatives of Serbian Orthodoxy in those times, were arrested by the occupiers in July 1941 because of their relationships with resistance fighters and interned in various monasteries. On September 14, 1944, they were transferred to the Dachau concentration camp , according to the statements of the priest monk and later bishop Atanasije Jevtić, because both refused to condemn the Communist Party on behalf of the Serbian Orthodox Church. In April 1945, Nikolaj Velimirović was released from the Dachau concentration camp to bless the Yugoslav national army and serve as a religious leader. The Yugoslav national army, Ljotić supporters who fled to Istria , Chetniks of the “Vojvoden” Đujić (who later emigrated to the USA) and the “General” Damnjanović who had fallen away from Mihailović, as well as the Slovenian Domobranci , had made the fight against the communist partisans their task. She tried to establish contacts with the western allies and called on the Yugoslav King Peter II , who was in exile in London, to come to Slovenia. Dimitrije Ljotić had a fatal accident in a car accident in Slovenia in April 1945, and Nikolaj Velimirović was returned to the Dachau concentration camp, where he and the Serbian patriarch were transferred to Kitzbühel and liberated by the 36th US Division on May 8, 1945.

Unlike the Patriarch, Nikolaj Velimirović did not return to the now communist Yugoslavia, but emigrated to the USA in 1946 after a short stay in Europe. In the USA, Velimirović became the mouthpiece of the Serbian emigrants who clung to the monarchy and rejected communist Yugoslavia.

Nikolaj Velimirović died in the USA on March 18, 1956 and was buried in a Serbian Orthodox monastery near Libertyville ( Illinois ). On May 3, 1991 , his remains were transferred from the United States to his birthplace in Lelić, Serbia, according to his legacy that his remains should be buried in his homeland.

Appreciation in Serbia

Although Velimirović spent a considerable part of his life in Western countries, his life and work, including his literary work, are little known, especially in non-Orthodox circles. Bishop Nikolaj is one of the most influential personalities in recent Serbian history. His ideas are still considered to be very influential within the Serbian Orthodox Church and Serbian politics. Velimirović enjoys the greatest recognition within Serbia and is considered one of the most important religious figures since the Middle Ages. His books are widely available in Serbian bookstores and have sold over a million copies in the last ten years alone. In the first half of the 20th century, Nikolaj Velimirović, Bishop of Ohrid and Žiča , one of the most respected Serbian clergymen, was famous for his charisma, expressiveness and talent. He often referred to himself as a "narodni radnik", a worker for the people.

Many Orthodox Serbs have long venerated Nikolaj Velimirović as a saint. The official canonization by the Orthodox Church took place only in 2003 under the patronage of the ecumenical patriarch Bartholomäus . The days of remembrance for the saint are March 18 (the day of his death) and May 3 (translation) in the calendar of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

Controversy

Velimirović is politically very controversial today, as his opponents accuse him of having represented anti-Semitic theses in his writings as early as the 1930s . In 1985, Serbian immigrant circles in Linz published a book that he is said to have written during the war years while he was being held in Dachau, under the title Srbima kroz tamnički prozor (Words to the Serbian People through a Dungeon Window), in which he blamed himself attributed to the war to the various "anti-Christian" ideologies in Europe and to the turning away of peoples from Christianity. Behind world views such as democracy, socialism, pacifism, capitalism or communism, Velimirović or the author saw the work of the Jews who are in the service of the devil . Today there is a strong discussion about the authenticity of the book in Serbian church circles and beyond, as the proponents of the authenticity of the book mostly take radical political or anti-church positions, while the opponents point out that there is no original of the book and that they believe the legend about the origin of the book is not credible (the book is said to have been written on toilet paper in the Dachau concentration camp and dragged along by Velimirović for decades), nor does the content correspond to the well-known political stance of Velimirović, who was known as an Anglophile throughout his life , while in the book England, which is "in the clutches of the Jews", is regarded as the root of all evil in the world.

Those who struggle with alleged anti-Semitism by Velimirović also point to the case of Ela Trifunović, née. Neuhaus, a Jew who was kept hidden with her mother by Velimirović for 18 months in the Ljubostinja monastery . Ela Trifunović wrote a letter to the Serbian public in 2001, in which she countered allegations of anti-Semitism against Velimirović at the time.

Fonts (selection)

- Belief in the resurrection of Christ. theol. Dissertation, Bern 1908.

- Franco-Slavic fighting in the Bocca di Cattaro 1806-1814. PhD thesis, Bern 1910.

- Religija Njegoševa. Belgrade 1911.

- Iznad greha i smrti. Besede i misli. Belgrade 1914.

- Serbia's place in human history. London 1915 (English).

- Serbia in light and darkness. London 1916 (English).

- Molitve na jezeru . Belgrade 1922 (In German translation under the title Gebete am See. 2004).

- Ohridske prolog . Niš 1928 (In German translation under the title Der Prolog von Ochrid. Verlag Johannes A. Wolf, Apelern 2009, ISBN 978-3-937912-04-2 ).

- Thoughts about good and bad (aphorisms) . Zurich 1932.

- Nacionalizam Svetog Save [The Nationalism of Saint Sava] . In: San o Slovenskoj Religiji [The dream of a Slavic religion] . Belgrade 1935 (new edition Belgrade 2001).

- Čiji si ti malo narode srpski? [Where do you belong, little Serbian people?] Belgrade 1939 (new edition Belgrade 2001).

- Vojna i Biblija. Novi Sad 1940.

- Tri molitve u sevici nemačkih bajoneta. Vienna 1945.

- Emanuil: s name bowed. Eboli 1947.

- Pobedioici smrti: pravoslavna čitanja za svaki dan godine. Hanover 1949.

- Zemlja nedođija: jedna moderna bajka. 1950.

- Pesme molitvene. Munich 1952.

- Kasijana. Nauka o hriščanskom pojmanju ljubavi. Munich 1952.

- Divan: nauka o čudesima. Munich 1953.

- Vera svetih. Katihizis Istočne pravoslavne crkve [The Faith of Saints: Catechism of the Orthodox Church] . Belgrade 1968 (In German translation under the title The faith of the orthodox Christians. 2008).

- Sabrana dela. 12 volumes, Düsseldorf 1976 ff.

- Izabrana dela. 10 volumes, Valjevo 1997 ff.

In 1960, the Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church German (1899–1991) supported the decision of the Synod to reissue Velimirović's Ohridske prolog (The Prologue of Ochrid) from 1928. After two printing houses rejected the order, the book could only be published after the entire text was looked through, ambiguous passages and Velimirović's name were deleted and the title was changed to Žitije Svetih (The Life of Saints).

After the end of the communist regime, numerous writings by Velimirović appeared in Yugoslavia. There are now some translations in German, such as The Prologue of Ochrid or the prayers at the lake .

In his novel "U Zemlji Negođiji" (free translation: In the Land of Unmute) , which he wrote after the Second World War , his political position is expressed once again, where the main hero in the ranks of Draža Mihailović fights against the fascist occupiers and to God for them Salvation of Serbs from the wicked prays.

literature

- Jovan Byford: Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović: 'Lackey of the Germans' or a 'Victim of Fascism'? In: Sabrina Ramet, Olga Listhaug (Ed.): Serbia and the Serbs in World War Two . Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, ISBN 978-0-230-34781-6 , pp. 128-152 .

- Jovan Byford: From “traitor” to “saint”. Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović in Serbian public memory [From traitor to saint: Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović in Serbian public memory] . Ed .: Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of Antisemitism (= Volume 22 of Analysis of current trends in antisemitism ). 2004 ( sicsa.huji.ac.il [PDF]).

- Milan Ristović: Velimirović, Nikolaj . In: Center for Antisemitism Research [Berlin], Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus. Hostility to Jews in the past and present . tape 2 . Saur, 2009, ISBN 978-3-598-24072-0 , pp. 850 f . ( books.google.de - short biography).

- Ljuba Ranković (ed.): O vladici Nikolaju [About Bishop Nikolaj] . Valjevo 2000.

- Rudolf Chrysostomus Grill: Serbian Messianism and Europe with Bishop Velimirović († 1956) . St. Ottilien 1998.

Web links

- Literature by and about Nikolaj Velimirović in the catalog of the German National Library

- Bratislav Božovic: A new saint of the Serbian Church: Bishop Nikolaj (Velimirovic). On the official website of the Commission of the Orthodox Church in Germany. Retrieved June 11, 2014 .

- The faith of God-loving people. Reflections on the Confession of the Orthodox Faith . 2010, translation into German: Johannes A. Wolf, PDF

swell

- ↑ Holm Sundhaussen : Bogomoljci . In: Conrad Clewing, Holm Sundhaussen (Hrsg.): Lexicon for the history of Southeast Europe . Böhlau Verlag, Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-205-78667-2 , p. 175 .

- ↑ a b Slobodan Kostić: Sporno slovo u crkvenom kalendaru. Retrieved June 12, 2014 .

- ↑ Nebojsa Popov: Srpski populizam. Od marginalne do dominantne pojave . Vreme, Beograd 1993.

- ↑ Klaus Buchenau: Orthodoxy and Catholicism in Yugoslavia 1945–1991. A Serbian-Croatian comparison (= Volume 40 of Balkanological Publications Eastern Europe Institute of the Free University of Berlin ). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2004, ISBN 978-3-447-04847-7 , p. 75 .

- ↑ Naličje kulta

- ^ Nikolaj Velimirović. A controversial life. (PDF) (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on September 21, 2013 ; Retrieved June 12, 2014 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Nikolaj Velimirović apostol nacionalizma

- ↑ a b Zvezdan Folić: Kosovski with u projekcijama srpske pravoslavne crkve. Retrieved June 12, 2014 .

- ↑ Klaus Buchenau: Orthodoxy and Catholicism in Yugoslavia 1945–1991. A Serbian-Croatian comparison (= Volume 40 of Balkanological Publications Eastern Europe Institute of the Free University of Berlin ). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2004, ISBN 978-3-447-04847-7 , p. 261 .

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Petar Rosic |

Archbishop of Ohrid 1920-1936 |

Plato |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Velimirović, Nikolaj |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Велимировић, Николај |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | orthodox bishop |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 4, 1881 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Lelić near Valjevo , Serbia |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 18, 1956 |

| Place of death | South Canaan , Pennsylvania, USA |