Serbia in World War II

| Србија | |||||

|

Srbija |

|||||

| Serbia | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Official language | Serbian | ||||

| Capital | Belgrade | ||||

| Head of government |

Milan Aćimović (until August 1941) Milan Nedić (1941–1944) |

||||

| surface | 51,000 km² | ||||

| population | 3,810,000 (1941) | ||||

| currency | Serbian dinar | ||||

| founding | 1941 | ||||

| resolution | 1944 | ||||

| National anthem | Ој Србијо, мила мати / Oj Srbijo, mila mati | ||||

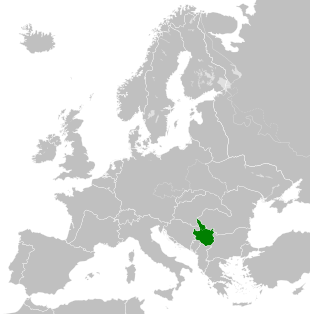

During the Second World War , Serbia was a vassal state of National Socialist Germany reduced to the so-called “ rest of Serbia ” and, as the “ territory of the military commander in Serbia ”, was under German military administration . It existed during World War II after the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was occupied and divided by the Balkans campaign (1941) . In Banat , a German civilian government was installed and around Kosovska Mitrovica an autonomous district formed.

The Serbian " Government of National Salvation " led by Prime Minister Milan Nedić , Cabinet Chief Nikola Kalabić and the secret police chief Dragomir Jovanović collaborated with the German occupying forces. The paramilitary associations of the Serbian State Guard and the fascist Serbian Volunteer Corps , which are directly subordinate to it, took part in the fight against the Yugoslav partisan movement and supported the occupiers in carrying out the Holocaust .

In October 1944, the Serbian capital, Belgrade , was captured by the Soviet Red Army and Tito's People 's Liberation Army (see: Belgrade Operation ). After the Second World War, Serbia became a republic of socialist Yugoslavia in 1945/1946 .

history

prehistory

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was neutral at the beginning of the Second World War . On March 25, 1941, the country joined the three-power pact , two days later the Yugoslav coup d'état of 1941 took place . Prime Minister Cvetković was overthrown by General Dušan Simović , and the young King Petar II took over in place of Prince Regent Paul . the governance. The new Yugoslav government tried to come to an understanding with the German Reich and concluded a friendship and non-aggression pact with Stalin on April 5, 1941. One day later, on April 6, 1941, the Axis powers began the Balkan campaign with an air raid on Belgrade . The Yugoslav government capitulated within eleven days.

After the quick victory over the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the country was divided into ten parts with different legal status. Serbia, consisting of old Serbia (the former territory of Serbia within the borders of 1912, excluding Macedonia ) and the West Banat , with a total of around 4.5 million inhabitants, was declared an exclusively German zone of influence due to its great economic importance and placed under military administration. The area covered more than a quarter of the total area of the former Yugoslavia. The raw and basic industries were particularly important for the German war economy, wheat and maize were also supplied to Germany . Of the areas that belonged to Serbia before 1941, Hungary occupied southern Baranja and Batschka , Bulgaria occupied most of Macedonia and Syrmia was added to the independent state of Croatia . Until the end of the war, the borders of Serbia between the Axis powers were shifted several times. The German Reich installed a collaboration government in Serbia .

German ethnic group

The Serbian Banat, with around 131,000 Serbian Germans and a Hungarian population, remained directly under German administration. From March 27, 1941, the sabotage department of the Abwehr Office, headed by Erwin von Lahousen, delivered large quantities of weapons to the German ethnic group . On April 6, 1941, ethnic group leader Sepp Janko placed the entire ethnic group under Lahousen's department in military terms. After the attack by the Axis Powers on Yugoslavia, the ethnic group's “self-protection commandos” attacked the Yugoslav army and expelled Yugoslav officials. Yugoslav Danube Swabians of military age also served in the Yugoslav army and fought against the German troops. Instead, many chose to flee to Styria , Hungary or Romania or hid until the German troops arrived. Janko received considerable autonomy powers in cultural and educational issues from the German occupying power , as well as jurisdiction over all ethnic Germans. This ethnic group, a National Socialist compulsory organization, was able to tax its members, call them up to serve in the police force and set up armed units that were exclusively subordinate to the ethnic group leader, such as the "local security" or the "Banat State Guard".

In the summer of 1944, after the coup in Romania on August 23, 1944, the coming military defeat became apparent. The evacuation plans of the German authorities initially encountered resistance from the leadership of the ethnic group and the SS leadership in Belgrade. When the Red Army advanced rapidly west in early October 1944, the evacuation was only partially successful. Large parts of the Danube Swabians did not want to leave their house and farm. Around half of the German population was evacuated from the Batschka , and only around 10 percent from the Banat .

German occupation and the insurgency movement

After the division of Yugoslavia, the German armed forces initially secured the remaining Serbian state with three divisions, the 704th, 714th and 717th infantry divisions. Security police and the security service operated in Serbia . The leadership of the police forces of the Serbian collaboration government and all SS forces was subordinate to the SS group leader August Meyszner . As commander of the Waffen-SS units, he was also responsible for setting up the 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division "Prinz Eugen" , whose teams were mainly recruited from the German minority in Serbia, especially from the Banat. Nevertheless, the Wehrmacht bore the main responsibility for the terrorist actions, including the Kraljevo and Kragujevac massacres ; she was responsible for "internal security". Predominantly Wehrmacht units carried out the terrorist policy, the SS and the police were subordinate to it de jure and, especially in large-scale operations, also tactically.

The uprisings in Serbia faced only insufficient German occupation troops . Hitler had determined that only two divisions should remain in Serbia , along with another division in the copper mining area between Morava and Danube . In order to win Serbian forces to fight the partisans , the "government" of General Milan Nedić was formed on August 29, 1941 . On September 1, 1941, Nedić proclaimed the state of Serbia. Nedić was defense minister in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, he was ideologically very close to fascism . Almost all parts of the old Serbian state apparatus were at his disposal.

The government of Nedić was supported militarily by Chetnik troops led by Dimitrije Ljotić . Milan Nedić also maintained close contacts with Colonel Dragoljub Draža Mihailović , who provided the Germans with valuable, and at times also armed, aid against the liberation movement. The Germans, however, were suspicious of his National Serbian movement; they were opposed to the “ Greater Serbian idea ”, especially since it also opposed the Ustasha regime. In addition, the National Serbian movement, protected by written agreements with the Germans, used the opportunity for further political expansion. Nevertheless, the OKW tried to make use of the Michailović-Četniks' associations for military purposes and in the summer of 1944 involved them in two major partisan operations. As a result, Nedić also unconditionally joined this anti-communist alliance. The Germans, however, continued to be suspicious of the alliance, but they still supplied it with weapons until the end of August 1944, albeit on a limited scale. When the Tito partisans massively attacked Serbia in September 1944 , they were able to break up the main units of the Michailović-Četniks, armed with German help. This made them militarily as well as politically meaningless.

The Nedić regime lasted until October 1944 when Soviet troops advanced across the Serbian borders. On October 20, 1944, Belgrade was liberated jointly by Tito's partisans and the Red Army .

Economic policy

As a result of partisan warfare and occupation, Serbia's economic production fell. As far as possible, his capacities were used for the occupying power, factories were given arms contracts. Serbia supplied a significant proportion of Germany's demand for copper and other raw materials. Large quantities of agricultural products, mainly maize, wheat and oil fruits , were brought to Germany, mainly from the Banat. In addition, the German and the state's own troops had to be fed. Hardly anything was made available to the civilian population. A large part of the equivalent of the goods delivered to Germany was paid in dinars , but Serbia could buy almost nothing for this currency in Germany. In addition, it had to bear the occupation costs. The result was an expansion of the money supply , which was offset by a shortage of goods, which led to inflation . The dinars in circulation rose almost tenfold from 1941 to 1944. Prices rose sharply, and the wage freeze to a large extent led to poverty and mass misery.

Forced labor and deportations

The copper mines of Bor was the largest industrial complex in Serbia for the German economy. It was headed by Siemens and the Todt Organization . In the autumn of 1942, around 30,000 Serbian workers were working in these mines and smelters to meet the needs of the German Reich for metals essential to the war effort. Only a third of them worked there voluntarily, the vast majority were forced laborers . Another 50,000 were "placed" as workers in the Reich. Although the Reich's need for slave labor increased sharply after the development on the German-Soviet front , the deportations from Serbia had to be stopped. Due to the influx of the liberation movement, which had increased after the suppression of the uprising in 1941/1942, there were not enough workers even for the production of the Wehrmacht. In July 1943, 6,000 Hungarian Jews were also employed as heavy laborers in the Bor mines , whose work was paid for with copper deliveries - the Yugoslav Jews had previously been murdered by the Germans. In addition, 4,000 Italian military internees were deployed.

Because of the labor shortage, Hitler finally ordered in the summer of 1943 that captured partisans should no longer be shot, but deported to work. According to the statistics of the Reich Labor Office, there were around 115,000 civilian workers from non-Croatian Yugoslavia in Germany in 1943, and around 100,000 in 1944. There were also around 100,000 prisoners of war from the old Yugoslav army.

The Hungarian Jews used as forced laborers were driven north on death marches in September 1944 . At least 700 of them were killed in an SS massacre near Crvenka . Some were able to flee to the partisans, the rest were taken to the Buchenwald , Flossenbürg and Sachsenhausen concentration camps , of which only a few survived.

Murder of Jews and Roma

In Serbia, the occupiers introduced racial laws , as a result of which Jews, Roma and opponents of the regime were systematically persecuted, brought to concentration camps and murdered. The two largest concentration camps on the territory of today's Serbia were the Sajmište concentration camp (at that time it belonged to the area of the city of Zemun and thus from 1941 to 1944 to the independent state of Croatia ) in which around 48,000 people were killed and the Banjica concentration camp , in which around 4,200 people were killed.

At the beginning of the German occupation, about 17,000 Jews lived in Serbia, which was under German military administration . Six weeks after the occupation began, Jews and Roma were registered, marked with yellow armbands, dismissed from offices and companies, deprived of their basic property, and forced to work. With the attack on the Soviet Union , Belgrade's Jewish community had to provide 40 men as hostages every day, who could be shot together with other “suspects” and arrested communists in response to partisan attacks. Although around 1,000 people had been hanged or shot as "expiatory measures" by the end of August 1941, this did not stop the partisan uprisings.

With the arrival of General Franz Böhme as Plenipotentiary Commanding General in September 1941, a targeted policy of extermination was adopted. Informed by the head of the military administration, Harald Turner , that the arrest of all Jews and Roma had been initiated, the occupation apparatus under Böhme decided not to deport the male Jews but to murder them on the spot. Prisoners were shot by the Wehrmacht in a ratio of 100 hostages for every fallen soldier and 50 hostages for every wounded soldier . In his first “atonement”, Böhme ordered 2100 prisoners from the concentration camps of Šabac and Belgrade to be shot. Among the first victims were more than a thousand Austrian Jews who were stranded in Yugoslavia while fleeing in late 1939.

In the winter of 1941/42, the remaining 7,000 Jewish women, children and old people as well as 500 Jewish men and 292 Roma women and children were imprisoned in the Sajmište concentration camp . Turner requested a gas truck for her murder at the turn of 1941/42 . Organized by the commander of the security police, Emanuel Schäfer and the concentration camp manager Herbert Andorfer , the Jewish camp inmates were murdered in this way from the beginning of March to the beginning of May 1942. Schäfer reported to the Reich Security Main Office : “Serbia is free of Jews !” In June 1943, the exploitation of the murdered people's assets began, primarily by selling them to the German ethnic group. As of November 1943, the bodies of the gassed victims were exhumed and cremated as part of the 1005 special campaign .

military

Serbian State Guard

The Serbian State Guard ( Serbian : Srpska državna straža , SDS for short) was founded on March 3, 1942 and served the police as support in the fight against the Tito partisans. The SDS was under the Serbian Interior Ministry. The head office was in Belgrade. When it was founded, the SDS comprised 17,000 soldiers and grew to almost 37,000 people by January 1943. Most of these were recruited from members of the Royal Yugoslav Army who were either not captured or had already been released.

Military collaboration

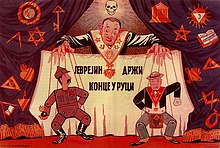

The Serbian government was supported in those years by Dimitrije Ljotić and the Chetniks of the fascist ZBOR movement. Before the war, the Zbor movement oriented itself towards Italian fascism. Similar to Ante Pavelić's Croatian Ustaša party, it showed a closeness to Christianity, but unlike the Roman Catholic-oriented Ustaša, it confessed to the Serbian Orthodox Church. The ZBOR movement called for the abolition of democracy and the establishment of an authoritarian corporate state. While it did not achieve a significant political majority in the Yugoslav parliament before the war, its influence increased considerably after the German occupation. She dedicated herself to the fight against Jews, Freemasonry, Communists and Western capitalism. Because of the extensive ideological affinity to National Socialism, Ljotić sided with the German occupiers from the start, who in turn accepted him as an unreservedly reliable ally. After the outbreak of the armed uprising in August 1941, the Zbor movement received the right to set up armed formations to fight the partisans. Due to their relatively small number, members of the movement mainly acted as translators, informants and advisers to the occupying power, and on several occasions as intermediaries between Mihailović and the occupiers. The ZBOR movement remained loyal to National Socialism beyond the end of the war and demanded the continuation of the struggle in the form of a guerrilla war.

The Serbian Volunteer Corps (Serbian: Srpski Dobrovoljački Korpus , SDK for short), in which the Ljotić units were organized in five battalions, was founded in September 1941. In February 1942 it had a strength of around 3,000 to 4,000 men and was commanded by General Kosta Mušicki , a former German-friendly officer in the Austro-Hungarian army.

At the end of December 1942, part of the SDK was transferred to the Waffen SS . This unit was named Serbian Volunteer Corps of the SS and, since October 1943, consisted of five regiments, which were initially formed from two and later three battalions. It was used on several fronts in the fight against the liberation movement. In December 1944 it was relocated to Istria, but fought there by the Ustaše . It was last stationed in Slovenia . Two of his regiments surrendered to British forces in Italy northwest of Trieste , the other three in the Drautal in Carinthia . These three regiments were handed over to Tito's partisans and murdered by them.

See also

literature

- Sabrina Ramet, Olga Listhaug (Ed.): Serbia and the Serbs in World War Two . Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, ISBN 978-0-230-34781-6 .

- Walter Manoschek : War crimes and the extermination of Jews in Serbia 1941–1942 . In: Wolfram Wette, Gerd R. Ueberschär (Ed.): War crimes in the 20th century . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2001, ISBN 3-89678-417-X , p. 123-136 .

- Martin Seckendorf, Günter Keber u. a .: The occupation policy of German fascism in Yugoslavia, Greece, Albania, Italy and Hungary (1941–1945) . Ed .: Bundesarchiv (= Europe under the swastika . Volume 6 ). Hüthig and RvDecker / CFMüller, Berlin / Heidelberg 1992, ISBN 3-8226-1892-6 ( ISBN 3-3260-0411-7 for the entire multi-volume document edition in the Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften).

- Walter Manoschek: Serbia is free of Jews. Military occupation policy and the extermination of Jews in Serbia 1941/42 (= series of publications by the Military History Research Office ). 2nd Edition. Munich 1995, ISBN 3-486-55974-5 .

- Karl-Heinz Schlarp: Economy and Occupation in Serbia 1941-1944. A contribution to the National Socialist economic policy in Southeast Europe . Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-515-04401-9 .

- Jewish Historical Museum Belgrade (ed.): We survived the Holocaust: Yugoslav Jews on the Holocaust. Federation of Jewish Communities in Serbia (or Yugoslavia), Aleksandar Gaon (compiler), Stephen Agnew & Jelena Babsek Labudović (transl.), Volume 1, Belgrade 2005, ISBN 86-903751-2-0 (40 contemporary witness reports) - Volume 2: 2006, ISBN 86-903751-4-7 (42 reports & several registers; English from Serbo-Croatian and others)

- Olivera Milosavljević: Potisnuta istina: Kolaboracija u Srbiji 1941–1944 [The suppressed truth: Collaboration in Serbia 1941–1944] . Ed .: Helsinški odbor za ljudska prava u Srbiji. Beograd 2006, ISBN 86-7208-129-3 ( org.rs [PDF]).

- Branko Petranović: Srbija u Drugom svetskom ratu 1939–1945 [Serbia in World War II 1939–1945] . Ed .: Vojnoizdavački i novinski centar. Beograd 1992 ( znaci.net ).

Web links

- Serbian Quisling government

- Notes on Serbian rights, Rosa Luxemburg Foundation (PDF; 72 kB)

- Myths for a New War. In: TAZ

- Detailed information about the Chetnik movement (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Daniela Mehler: Serbian coming to terms with the past: Change of norms and struggles for interpretation in dealing with war crimes 1991–2012 (= Global Studies ). transcript Verlag, 2015, ISBN 978-3-8394-2850-4 , pp. 63 .

- ↑ Federal Archives (ed.): Europe under the swastika, The occupation policy of German fascism in Yugoslavia, Greece, Albania, Italy and Hungary (1941-1945). Volume 8, Hüthig Verlagsgemeinschaft, ISBN 3-7785-2338-4 , pp. 275 f.

- ^ Johann Böhm : The German ethnic group in Yugoslavia 1918–1941 . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2009, p. 339 .

- ^ Immo Eberl , Konrad G. Gündisch, Ute Richter, Annemarie Röder, Harald Zimmermann : Die Donauschwaben. German settlement in Southeast Europe. Exhibition catalog (published by the Ministry of the Interior of Baden-Württemberg), Wiss. Management d. Exhibition Harald Zimmermann, Immo Eberl, employee. Paul Ginder, Sigmaringen 1987, ISBN 3-7995-4104-7 , p. 258.

- ^ Klaus Schmider : The Yugoslav theater of war. In: Karl-Heinz Frieser, Klaus Schmider, Klaus Schönherr , Gerhard Schreiber , Krisztián Ungváry , Bernd Wegner : The German Reich and the Second World War. Volume 8: The Eastern Front 1943/44 - The War in the East and on the Side Fronts. on behalf of the MGFA ed. by Karl-Heinz Frieser . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-421-06235-2 , p. 1043 ff.

- ↑ Mark Spoerer: Forced labor under the swastika. Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Stuttgart / Munich 2001, ISBN 3-421-05464-9 , p. 68.

- ↑ Walter Manoschek: “Are you going to shoot Jews?”. The extermination of the Jews in Serbia . In: Hannes Heer u. Klaus Naumann (Ed.): War of Extermination, Crimes of the Wehrmacht 1941–1944 . Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 1995, p. 39.

- ↑ Walter Manoschek: “Are you going to shoot Jews?”. The extermination of the Jews in Serbia . In: Hannes Heer u. Klaus Naumann (Ed.): War of Extermination, Crimes of the Wehrmacht 1941–1944 . Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 1995, pp. 39–42.

- ↑ Walter Manoschek: “Are you going to shoot Jews?”. The extermination of the Jews in Serbia . In: Hannes Heer u. Klaus Naumann (Ed.): War of Extermination, Crimes of the Wehrmacht 1941–1944 . Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 1995, p. 42.

- ↑ Walter Manoschek: “Are you going to shoot Jews?”. The extermination of the Jews in Serbia . In: Hannes Heer u. Klaus Naumann (Ed.): War of Extermination, Crimes of the Wehrmacht 1941–1944 . Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 1995, p. 44.

- ↑ Walter Manoschek: “Are you going to shoot Jews?”. The extermination of the Jews in Serbia . In: Hannes Heer u. Klaus Naumann (Ed.): War of Extermination, Crimes of the Wehrmacht 1941–1944 . Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 1995, p. 45 f.

- ↑ Walter Manoschek: “Are you going to shoot Jews?”. The extermination of the Jews in Serbia . In: Hannes Heer u. Klaus Naumann (Ed.): War of Extermination, Crimes of the Wehrmacht 1941–1944 . Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 1995, p. 51 f .; Walter Manoschek: "Serbia is free of Jews": Military occupation policy and the extermination of Jews in Serbia 1941/42 . 2nd ed., R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1995, pp. 171-182.

- ^ Walter Manoschek: "Serbia is free of Jews": Military occupation policy and the extermination of Jews in Serbia 1941/42 . 2nd edition, R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1995, p. 184.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Schlarp: Economy and Occupation in Serbia. 1941-1944. A contribution to the National Socialist economic policy in South Eastern Europe (= sources and studies on the history of Eastern Europe. 25). Steiner-Verlag-Wiesbaden, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-515-04401-9 , p. 320, here p. 301. (also: Hamburg, Univ., Habil.-Schr., 1983)

- ^ Walter Manoschek: "Serbia is free of Jews": Military occupation policy and the extermination of Jews in Serbia 1941/42 . 2nd edition, R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1995, p. 183.