Treaty of Sèvres (Ottoman Empire)

The Treaty of Sèvres (also Peace of Sèvres ; Turkish Sevr Antlaşması ) of August 10, 1920, between the British Empire , France , Italy , Japan , Armenia , Belgium , Greece , the Hejaz , Poland , Portugal , Romania , the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and Czechoslovakia as the victorious powers of the First World War and the Ottoman Empire was one of the Parisian suburban treaties that formally ended the war. It was a so-called dictation peace . The treaty was ratified due to the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the fall of the last sultan, Mehmed VI. no more. The Turkish Liberation War , which had already begun , continued unabated.

content

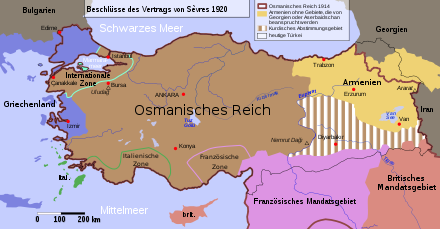

According to the Treaty of Sèvres, the Ottoman Empire should lose much of its territory. The Sublime Porte renounced their possessions in Syria and Mesopotamia (Section VII of the Treaty). League of Nations mandates should be established in these areas . At the same time, the Arabic-speaking provinces in the Middle East and North Africa were to be divided among France, Italy and Great Britain. In Palestine , with reference to the Balfour Declaration, a national home for the Jewish people was to be established. On the Arabian Peninsula , the Hejaz , conquered by the Najd Sultanate in 1925, was constituted as the new independent kingdom of Hejaz and the rights of the Ottoman Empire in this part of Arabia were transferred to it. The right of access to the holy sites of Medina and Mecca was regulated (Section VIII of the Treaty).

Eastern Thrace (with the exception of Constantinople and its immediate vicinity) was to be ceded to Greece. Bulgaria had already had to cede western Thrace to Greece in the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine . To this end, Greece concluded two further treaties with the other allies, one with regard to western Thrace and one for the protection of minorities . In the east, the pre-war border was restored, the Ottoman Empire lost the territorial gains achieved in the peace of Brest-Litovsk .

The annexation of Cyprus by Great Britain in 1914 was sanctioned, the British protectorate over Egypt proclaimed in 1914 was recognized and sovereign rights and tribute rights of the Ottoman Empire in its former vassal state were renounced. The agreements between Egypt and Great Britain over Sudan were also recognized by the Ottoman Empire (Section IX of the treaty).

The French protectorates over Morocco and Tunisia were recognized (Section IX); the reserve rights of the Sultan in Libya, which were reserved in the Treaty of Ouchy in 1912, were revoked and Italian rule over the islands of the Dodecanese , which had been occupied by Italy since 1912 , enlarged to include the island of Kastelorizo , were recognized and the sovereign rights were renounced in favor of Italy (Section X of the Treaty).

For the future, further assignments of territory were in prospect, which the Ottoman Empire had to agree to in advance.

With the nominal Ottoman sovereignty still in place, Smyrna and the surrounding area were administratively separated from the Ottoman state under a local parliament and placed under Greek administration and occupation . After a five-year transition period, the local parliament should decide, after an optional referendum, whether the area should be part of Greece.

The future border with Armenia should be determined by a decision of the American President, and Armenia should also be able to gain access to the Black Sea; This Wilson line was already obsolete at the time of its creation by the military events of the Turkish-Armenian War and the fact that the United States was not one of the signatory states of the Treaty of Sèvres.

Predominantly Kurdish areas east of the Euphrates and south of the Wilson Line were to be given autonomy in accordance with Article 62 , and Article 64 also promised possible state independence. To do this, the Kurds had to prove to the League of Nations within a year of the treaty's entry into force that the majority of the Kurds wanted independence from Turkey. Furthermore, the League of Nations would decide whether the Kurdish population was ripe for independence. In the event of independence, the Allies agreed to tolerate the voluntary annexation of the Kurdish parts of the former Vilayets Mosul to the Kurdish state.

In addition, the people of the Assyrians or Chaldeans , who have lived in this area for centuries, were given explicit minority protection. The claims of the Kurds and the Armenians on Anatolian soil overlapped several times. While Armenia sat at the negotiating table on an equal footing with European small states such as Belgium or Czechoslovakia , the Kurdish delegation led by the Ottoman-Kurdish diplomat Mehmet Serif Pascha was “not even given a table ”. Since the Kurds had no powerful advocates like the Armenians, their spokesman was content with an autonomous area that comprised only a third of the Ottoman Kurdish population. This mention by name was later omitted in the Treaty of Lausanne .

In the following articles, the treaty contained provisions on the regulation of citizenship, the protection of minorities, the prosecution of war crimes, the almost complete dissolution of the Ottoman armed forces except for an honor guard of the sultan and police forces, demilitarization and international control of the straits, prisoners of war and war graves, economic and financial provisions and in particular the waiver of all rights of any kind outside the new borders of the Ottoman state and outside Europe (Art. 132).

Happenings

The Treaty of Sèvres formed the final stage of several treaties, agreements and declarations by the Entente powers that had won the world war. The contract was signed by agents of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed VI. and signed by the Ottoman government under Grand Vizier Damad Ferid Pasha (but not by himself) amid violent protest. The ratification of the treaty by the Ottoman parliament never took place because the sultan had already dissolved the parliament in March 1920. The treaty was also rejected by the national movement under Mustafa Kemal in the rest of Turkey .

Articles 226 to 230 provided for the establishment of international military courts to prosecute war crimes committed by the Ottomans. Under pressure from the victorious powers of the First World War (especially the British), national military courts had been tried in the Ottoman Empire since the beginning of 1919 (unionist trials). Because, on the one hand, there was a lack of jurisprudence at international level according to which individuals could be convicted of complicity in collective crimes, and on the other hand, there were conflicting views and interests between the victorious powers, there was no international prosecution.

It remained with the national Turkish military courts in 1919/1920 . These in turn lost more and more importance over time due to the chaos prevailing in the country (occupation of Smyrna by the Greeks in 1919, the Turkish liberation movement under Mustafa Kemal, the interference of the British in the processes through arrests and extraditions to Malta) and finally became part of it of the Allied plan to partition the Ottoman Empire and banned one day after the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres on August 11, 1920 by the government in Ankara under Mustafa Kemal. With the abdication of the cabinet of the Istanbul Sultan's government under Grand Vizier Damat Ferid on October 17, 1920, the courts completely lost their importance. After the Allied occupation of Istanbul on March 16, 1920, efforts were made to found the Grand National Assembly in Ankara. After the establishment of the National Assembly in Ankara on April 23, 1920, there were two hostile governments in the country.

There were several reasons for the harsh terms of the Treaty of Sèvres. In addition, the genocide of the Armenians, the memory of the Allies of the loss-making battle of the Dardanelles in 1915, the efforts of the victorious powers to divide the Ottoman Empire (which had already been decided before and during the war in secret negotiations, such as the Agreement on Constantinople and the Straits ) was) and the centuries-long project to oust the Turks from Europe counted. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George said that the war and the defeat of the Turks had provided an opportunity to "solve this problem once and for all". On December 18, 1916, the Allies had announced to US President Wilson that they would "liberate the peoples who were subject to the bloody tyranny of the Turks".

The French Foreign Minister had declared on January 10, 1917: “The lofty goals of the war include the liberation of the peoples currently subject to the murderous tyranny of the Turks and the ousting from Europe of the Ottoman Empire, so completely alien to Western civilization ".

Other comments by important Allied statesmen on the Treaty of Sèvres were: “When the peace conditions are announced, it will be seen what harsh sentences the Turks are sentenced to for their madness, their blindness and their murders. [...] The punishments will be so terrible that even their worst enemies will be satisfied. ”(Lloyd George) Curzon described Turkey in a statement on July 4, 1919 as“ a criminal waiting to be tried ”. “What will happen to Mesopotamia has to be decided in the sessions of the Peace Congress, but one thing will never happen. It will never be left to the damned tyranny of the Turks again. ”(Lloyd George, December 20, 1917)

As League of Nations mandates , Mesopotamia ( Kingdom of Iraq ) and Palestine were given to Great Britain , Syria and Lebanon to France , Eastern Thrace and Smyrna came to Greece. The Bosphorus and the Sea of Marmara should be demilitarized and placed under international control.

consequences

With its extremely harsh conditions, the Treaty of Sèvres went far beyond the extent of the Treaty of Versailles . The Treaty of Versailles weakened the German Empire , but the Treaty of Sèvres questioned the very existence of an independent Turkish state.

At the time the contract was concluded, however, it was already becoming apparent that the prospects of enforcing the provisions of the contract were slim. The United States was already in the process of returning to isolationist policies; the American President Woodrow Wilson, whose term of office was coming to an end, was severely restricted in his ability to act as a result of a stroke. The United Kingdom and France were severely weakened by the loss of people and economic values in World War I, and were faced with local uprisings in the newly acquired areas of Syria and Mesopotamia. In addition, the main concern of the French government was to enforce the provisions of the Versailles Treaty against Germany. The Russian civil war after the October Revolution also claimed the attention of the Allies. At the time of the conclusion of the contract, the Red Army had already penetrated as far as Warsaw during the Polish-Soviet War and the collapse of Poland was feared. Italy had also claimed the Smyrna area assigned to Greece and, because this and other of its war aims were disappointed, began with a policy of obstruction.

On the other hand, before its overthrow and the armistice, the Young Turkish government had created the organizational and logistical prerequisites for resistance in Anatolia. The Young Turkish Movement was particularly well networked among the younger civil service and military leadership. If it was initially discredited by the lost war, it soon won back the support of the Muslim public thanks to its humiliating occupation policy. An increasingly Turkish nationalism gripped the entire Muslim population. Both the National Committee in Ankara, Anatolia, and the last Ottoman Parliament jointly developed their ideas for a post-war order in the Misak-ı Millî (National Pact ). The Allies were able to get their will against the Sultan's government in occupied Istanbul, but this only led to the Sultan's government being viewed as being prevented from carrying out its government activities and a national assembly being constituted in Ankara. The Turkish resistance in Anatolia had become so strong militarily that the Turkish Liberation War had already broken out in full. The Treaty of Alexandropol , which ended the Turkish-Armenian War on December 2, 1920 as a partial conflict of the Liberation War, reversed the provisions and intentions of the Treaty of Sèvres with regard to Armenia less than 5 months later.

Of all the states involved, only Greece under its Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos believed that it could break the Turkish resistance by force of arms. The crossing of the demarcation line of the Smyrna area by Greek troops triggered the Greco-Turkish War as a further partial conflict. The Treaty of Sèvres had no impact on these fighting during the Turkish Liberation War.

The signing of the Treaty of Sèvres by his plenipotentiaries led to a lasting shock to the reputation and authority of the sultan among the Turkish population and laid the foundation for the later abolition of the monarchy. The nationalists in Ankara rejected the treaty, declared themselves the legitimate government and resisted the Greek army in the Greco-Turkish war. As a result of the Turkish Liberation War, the Treaty of Sèvres was revised in the Treaty of Lausanne in favor of Turkey. The signatories of the Treaty of Sèvres were declared traitors to the fatherland by Ankara on August 19, 1920, on which the death penalty stood.

By the end of 1922, both the sultan's government in Istanbul and the resisting national government in Ankara existed. On November 1, 1922, the national government declared the sultanate abolished, on November 4, the last Ottoman government in Istanbul under Ahmed Tevfik Pasha resigned, and on November 6, the nationalists took Istanbul. Thus, the national government was only in power in the country shortly before the start of the Lausanne Peace Conference, to which both governments were invited.

The fear that exists in Turkey that the great powers would have wanted to split up Turkey is known as Sèvres syndrome after the place of the contract .

literature

- Roland Banken: The Treaties of Sèvres in 1920 and Lausanne in 1923. An international legal investigation into the end of the First World War and the resolution of the so-called "Oriental Question" through the peace treaties between the Allied powers and Turkey . Lit Verlag, Berlin 2014, ISBN 3643125410 .

- Paul C. Helmreich: From Paris to Sèvres. The Partition of the Ottoman Empire at the Peace Conference of 1919-1920 . Ohio State University Press, Columbus / OH 1974, ISBN 0814201709 .

- Jörn Leonhard : The overwhelmed peace. Versailles and the world 1918–1923. CH Beck, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3406725067 .

- Andrew Mango : From the Sultan to Ataturk. Turkey (= Makers of the Modern World. The Peace Conferences of 1919-23 and their Aftermath ). House Publishing, London 2009, ISBN 1905791658 .

Web links

- Text of the Treaty of Sèvres (English)

- Newspaper article about the Treaty of Sèvres in the press kit of the 20th century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

supporting documents

- ↑ Treaty of Sèvres, Article 62 ( online documentation ).

- ↑ Klaus Kreiser, Christoph K. Neumann: Small history of Turkey . Reclam, Stuttgart 2009, p. 379.

- ^ Statement by Lloyd George in Gotthard Jäschke : Mustafa Kemal and England in a new perspective. In: Die Welt des Islams, Volume 16 (1975), pp. 166–228, here p. 225.

- ^ Gotthard Jäschke: Kurtuluş Savaşı ile ilgili İngiliz Belgeleri ( English documents on the war of liberation ). Türk Tarih Kurumu, Ankara 1971, p. 54.

- ^ Harold WV Temperley: History of the Peace Conference of Paris . Vol. 6, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, London / New York / Toronto 1969, p. 23.

- ↑ Lloyd George: The Truth about the Peace Treaties , London 1938, Volume 2, p. 64.

- ↑ Tarık Zafer Tunaya: Türkiye'de Siyasi Partiler ( Political parties in Turkey ). Vol. 2, Hürriyet Vakfı Yayınları, Istanbul 1989, p. 27.

- ^ Ernest Llewellyn Woodward, Rohan Butler: Documents on British Foreign Policy 1919–1936 . First Series, Vol. 4. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1952, p. 661.

- ^ Richard G. Hovannisian: The Allies and Armenia, 1915-18 . In: Journal of Contemporary History , Volume 3 (1968), p. 148.

- ↑ Eugen Krieger: Turkey's candidate for Europe: the decision-making process of the European economic community during the association negotiations with Turkey 1959–1963 , Chronos, Zurich 2006, ISBN 3034007604 , page 27 in the Google book search.

- ↑ a b Ines Kallis: Greece's way to Europe: the struggle for democratic structures in the 20th century . Theophano-Verlag, Münster 1999, ISBN 3980621049 , p. 85 in the Google book search.

- ^ Isaiah Friedman: British Miscalculations. The Rise of Muslim Nationalism, 1918-1925. Transaction Publishers, London 2012, ISBN 1412847494 , p. 217.

- ^ Michael Mandelbaum: The Fate of Nations: The Search for National Security in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1988, ISBN 9780521357906 , p. 61 in Google Book Search (footnote 55).

- ↑ TBMM Zabıt Ceridesi ( Parliamentary Protocols of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey ), Volume 3, p. 299.