Italo-Turkish War

| date | September 29, 1911 to October 18, 1912 |

|---|---|

| place | Tripolitania , Cyrenaica , Aegean Sea , Eastern Mediterranean , Red Sea , Tihama of Yemen |

| output | Italian victory |

| Territorial changes | Tripolitania (including Fezzan ) and Cyrenaica become Italian protectorates, the Dodecanese are occupied by Italy, and Sollum is occupied by Egypt |

| consequences | Resistance of the Libyan population against the Italian occupation (until 1918 with Ottoman support) |

| Peace treaty | Peace of Ouchy |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Imamat Asir ( Idrisiden ) |

|

| Commander | |

|

|

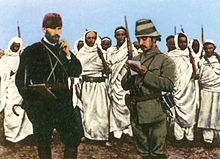

Tripoli: Colonel Neschat Bey (Commander) Major Ali Fethi Bey Talaat Bey Major Nasmi Bey Major Mehmed Musa Bey Halil Bey Lieutenant Colonel Muheddin Bey Major Mehmed Schefik Bey Cyrenaica: Major Enver Bey (Commander) Major Aziz Ali Bey al-Misri Major Abd el-Kader Bey Major General Edhem Pasha Major Mustafa Kemal Bey Shakir Bey

|

Tripoli - Mechiya Oasis - Al-Hani - Preveza - Kuwayfia - Tobruk - Ain Zara - Al-Qunfudha - Beirut - Al-Fwaihat - Derna - Rhodes - Zanzur - Misrata - Sidi Bilal

The Italian-Turkish War , Ottoman-Italian war or Tripolitan ( Italian Guerra di Libia , Libya war '; Turkish Trablusgarp Savaşı , Tripolitanienkrieg') was a military conflict between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire , which especially in the Mediterranean and North Africa held has been. It began with the Italian declaration of war on September 29, 1911 and ended with the Peace of Ouchy on October 18, 1912. In it, the Ottoman Empire Tripolitania , Cyrenaica and the Dodecanese ceded to Italy.

prehistory

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Kingdom of Italy was a country with many economic and social problems. The industrial development could not keep up with that of the western states; the population was largely poor and the state budget unbalanced; Protest movements were suppressed by the government in some cases with violence, while the current census system excluded large sections of the population from political life. As a direct consequence of this, between 1901 and 1911 alone, around 1.6 million Italians chose to emigrate to South America and the United States .

Against this background, the idea propagated by the nationalist-intellectual Associazione Nazionalista Italiana emerged to solve the country's social problems through colonial expansion. The major daily newspapers took up the suggestion and declared that the provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica , which were part of the Ottoman Empire , were cheap and close alternatives to the American continent for Italian emigrants, because there was enough fertile land there. However, this did not correspond to the facts, since only the densely populated coastal regions offered fertile soil at all.

The Italian government under Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti took up these popular ideas in late summer 1911, while parliament was still in the summer recess. The war against the Ottoman Empire was intended to divert attention from domestic political problems and increase the government's popularity. In terms of foreign policy, the approach seemed favorable at this point in time. While Italy's partners in the Triple Alliance , that Austria-Hungary and the German Reich refused an Italian aggression in North Africa - Berlin disliked the idea of a clash of his partner Italy with his friend, the Ottoman Empire, in Vienna warned Foreign Minister Aehrenthal from unwanted consequences on the Balkans - encouraged in particular Russia and the British Foreign Minister Edward Gray included the Italians in their plans. They saw in it both a weakening of the Ottoman influence and an expression of the Italian discontinuity within the Triple Alliance. The concerns of Berlin and Vienna did not impress the Italian government, but the signals from London and Saint Petersburg reinforced it. The Ottoman Empire was generally considered weak and it seemed unlikely to the Italian government that it would be able to offer any significant resistance. On September 26, 1911 , she presented the Sublime Porte with an ultimatum demanding the immediate cession of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. When Sultan Mehmed V (1844-1918) rejected the demands, the Italian government officially declared war on September 29.

Course of war

Battles and atrocities

First, the Italian Navy tried to secure naval supremacy in the Adriatic and Ionian Seas . On September 29 and 30, 1911, three Ottoman torpedo boats were sunk off the Albanian coast, whereupon the Italian ships were able to patrol the Ottoman coast almost unhindered. The Ottoman government was thus deprived of the ability to bring reinforcements to North Africa by sea.

The Italians then turned against Tripolitania with an expeditionary army of around 40,000 men, where they began shelling the city of Tripoli on October 3rd . The following day, Italian troops landed under General Carlo Caneva (1845-1922) and took the city. Also on October 4th, the poorly defended Tobruk fell into Italian hands. By October 14th, Derna and all the other important coastal towns in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, such as Homs and Benghazi , were also taken.

Contrary to what was expected, the local population, who lived relatively independently under Ottoman rule, greeted the Italians not as liberators but as hostile invaders. The influential Sanussiya Order, which had previously competed with the Ottoman administration, also took part in the fight against the invaders. The local tribes of Arabs and Berbers , along with the few Ottoman troops, withdrew inland. After a bloody skirmish near Sciara Sciat (near Tripoli) on October 23, 1911, the Italian occupation forces launched a pogrom against the Arab population, which they accused of treason. Thousands of Arabs were shot indiscriminately within five days , their huts burned and their cattle confiscated. In the weeks that followed, the occupying power carried out mass executions in public places and deported around 4,000 Arabs to penal islands such as Tremiti and Ponza . Nevertheless, the Italian advances did not get beyond the coastal oases in the months that followed. Instead, the troop strength had to be increased to 100,000 men.

Since Italy was now in a stalemate in the North African provinces, which it had formally annexed on November 5, 1911 , it tried with the help of the navy to force the Ottoman Empire to conclude peace. On January 7, 1912, the Italian units attacked the port city of Hodeida in the Red Sea and destroyed seven obsolete Ottoman gunboats in its port. On February 24, there was a minor skirmish off Beirut , in which the Italian armored cruisers Varese , Garibaldi and Ferruccio sank the old Ottoman coastal armored ship Avn-i-Illah and a torpedo boat. But even after that, the Ottoman government refused to accept the Italian demands. The Italian naval command therefore decided to attack the Ottoman coastal waters themselves. On April 18, 1912, they shelled the coastal forts at the entrance to the Dardanelles and in May they conquered the island of Rhodes and the surrounding smaller islands (= Dodecanese ) against little resistance .

For the first time in history, aerial bombs were also used as part of the fighting .

War in yemen

At the beginning of the 20th century, Muhammad bin Ali al-Idrisi gained religious influence in Sabya and the surrounding area. He pacified the feuding tribes there and ensured their obedience. Muhammad al-Idrisi rose to become the de facto ruler in this region, which was formally part of the Ottoman Vilayet Yemen , but initially remained loyal to the Ottoman Empire . After new taxes were levied in 1908, Muhammad al-Idrisi called for an uprising, which some surrounding tribes joined. This was the beginning of a ten-year conflict between the Idrisids , who were followers of Muhammad, and the Ottomans, which only ended with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

With the help of the Emir of Mecca, Hussein bin Ali , the Idrisids were defeated in July 1911 and driven out of Abha . In order to finally put down the uprising, the Ottomans prepared another campaign in September 1911, but this could not be carried out because of the Italian declaration of war. Italian warships were already active on the Red Sea in the first days of the Ottoman-Italian War . On October 2, 1911, the gunboats Arethusa and Vulturno bombed the coastal city of Hudaida , which led to the Zaidites entering the war on the part of the Ottoman Empire. However, some Zaidi tribes defected to the Idrisids, because a few months earlier the Zaidi had revolted against the Ottomans.

In the face of a common enemy, there was military cooperation between Italy and the Idrisids. At the beginning of October 1911 the Ottoman commander Muhammad Ali Pasha withdrew from the city of Jazan because he feared a joint operation by the Italians and the Idrisids against his troops. Thereupon the city was taken by the Idrisiden without a fight. The Italian fleet focused on bombing and blocking enemy ports on the coast of Yemen for the next few months . In February 1912 the Idrisiden received seven pieces of artillery, 3,000 out of date rifles, money and food from the Italians. With artillery support from Italian warships, Maidi was captured on February 29th . A fleet of eleven ships was assembled and armed there, which was able to drive the Ottomans from the Farasan Islands in June . After defeating Faisal bin Hussein's troops , the Idrisids captured Muhail in June . However, the attack on Qunfuda could be repulsed and further penetration into the area of the emirate of Mecca was prevented.

After the end of the Ottoman-Italian War, both the Ottomans and the Idrisids were not interested in further military action. With the peace agreement between the Ottoman Empire and Italy on October 18, 1912, the Idrisids lost their only source of supplies and their only (informal) allies. The Ottomans, on the other hand, were militarily bound by the Balkan War , so that no forces could be raised for a campaign against the insurgents. Both parties entered into negotiations, which failed in May 1913 due to excessive demands on the part of Muhammad bin Ali al-Idrisis, whereupon the revolt of the Idrisids continued.

Balance sheet

Even contemporary publications assumed that the Italian casualties from October 3, 1911 to March 2, 1912 amounted to 536 fallen officers and soldiers and 324 missing persons. By the end of the state of war with the Ottoman Empire on October 18, 1912, the total losses amounted to 1,432 fallen Italian soldiers.

The losses of the Ottoman Arab troops and population can only be estimated. According to official Italian figures, they lost 4,300 men in the first three weeks of the war, compared to 118 Italians. The Soviet historian Boris Zesarewitsch Urlanis later pointed out, however, that the battle losses of the Arabs were on average always about three times higher than those of the Italian troops. The total losses of the Ottoman-Arab troops would therefore be estimated at around 4,500 men. In addition, there was the number of killed Arab civilians, which is even more difficult to estimate, but was already taken as very high by contemporaries. Lenin (1870–1924) therefore called the whole war "a perfected, civilized massacre, a slaughter of the Arabs with the most modern weapons" and named a number of 14,800 Arabs killed.

During the war there was both the first reconnaissance flight and the first air raid in history with Blériot XI aircraft . On October 23, Captain Carlo Piazza explored an Ottoman position near Benghazi from the air. On November 1, 1911, Lieutenant Giulio Cavotti dropped the first two-kilogram bombs on living targets over two oases near Tripoli. The attack served no military purpose, but took place as part of the "retaliatory actions" against the Arab population after the battle at Sciara Sciat. In March 1912, Piazza returned with the first photographs on the occasion of a reconnaissance flight.

Peace treaty and consequences

The war against Italy revealed the weakness of the Ottoman Empire. As a direct consequence of this, in the spring of 1912 the countries of Serbia, Bulgaria, Montenegro and Greece allied themselves in the Balkan Alliance against the High Porte and attacked in October of the same year, the First Balkan War broke out. This threat to the northern border posed a greater and more massive threat to the Ottoman government than Italian colonialism aimed at remote provinces. She therefore found herself ready to negotiate peace in the autumn. On October 18, 1912 were in the district of Ouchy in Lausanne peace terms agreed. In the so-called Peace of Ouchy , the Ottoman Empire had to cede Tripolitania and Cyrenaica to Italy, which also held the Dodecanese.

After the conclusion of the peace treaty, the Italian army focused on the systematic submission of the new colonies of Italian Libya and Italian Dodecanese . Even after the peace was concluded, the Ottoman Empire secretly supported the local Arab resistance movement in North Africa, which was mainly supported by the Sufi Order of Sanussiya . Its leader Ahmad al-Sharif used his high spiritual reputation to call for a jihad against the foreign invaders, not only in Libya, but in the entire Muslim world. Due to the tough resistance, the Italian colonial troops had only brought a third of today's Libyan territory under control at the beginning of the First World War . When numerous troops then had to be shipped to Europe, the Italian armed forces fell heavily on the defensive. In the summer of 1915 only Tripoli and Homs were under Italian rule.

From 1922 onwards, under Benito Mussolini , Italy again focused on conquering colonies. In order to legitimize them, the Italian fascists cited that "an overpopulated nation without natural resources has a natural right to seek compensation overseas" . The Roman Empire served as a model . What was new about the conception was that it aimed not only at subjugating the tribes, but also at driving them out of the fertile coastal regions in order to make room for Italian colonists. Expropriations and expulsions were therefore the order of the day, while the occupying power, equipped with modern military equipment, acted with extreme severity against guerrillas and insurgents. From 1928 poison gas was also used . In order to rob the resistance movement of its base, around 100,000 Arab semi-nomads were deported in the summer of 1930 and interned in 15 concentration camps in the desert. Almost half of the inmates died there by the summer of 1933. In January 1932 Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were finally considered "pacified". But already in 1943, after the defeat of the Axis Powers in North Africa during the Second World War , both areas were placed under Franco-British administration and finally granted independence as Libya in 1951 .

literature

- Ahmed M. Ashiurakis: A concise history of the Libyan struggle for freedom , General Publications Distributing and Advertising Co., Tripoli 1976.

- William Clarence Askew: Europe and Italy's acquisition of Libya 1911–1912 , Duke University Press, Durham / North Carolina 1942.

- Hermann von dem Borne: The Italo-Turkish War (2 vols.), Stalling Verlag, Oldenburg 1913.

- Robert Hoppeler: The Italian-Turkish War , Verlag beer in Komm., Zurich 1911.

- Orhan Kologlu: The Islamic public opinion during the Libyan war 1911–1912 , Libyan Studies Center, Tripoli 1988.

- William K. MacClure: Italy in North Africa - An account of the Tripoli enterprise , Darf Publications, London 1986. ISBN 1-85077-092-1 .

- Ferenc Majoros , Bernd Rill : The Ottoman Empire 1300-1922 , Bechtermünz Verlag, Augsburg 2002. ISBN 3-8289-0336-3 .

- Aram Mattioli: Libya, Promised Land - Genocide in the desert sands . In: Die Zeit , No. 21, May 15, 2003 (online, zeit.de).

- Adolf Sommerfeld: The Italo-Turkish War and its Consequences , Continent Verlag, Berlin 1912.

- Charles Stephenson: A Box of Sand: The Italo-Ottoman War . Tattered Flag Press, Ticehurst 2014. ISBN 0-9576892-2-5 .

- Luca Micheletta / Andrea Ungari (eds.): The Libyan War 1911-1912 . Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013, ISBN 978-1-4438-4837-4 .

- Felix A. Theilhaber: At the red crescent moon in front of Tripoli - travel experiences from a trip to the Turkish-Italian war zone , Verlag Schaffstein, Cöln am Rhein 1915.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Aram Mattioli: Libya, promised land , in: DIE ZEIT, No. 21 (2003)

- ↑ Christopher Clark : The Sleepwalkers. As Europe moved into the First World War . From the English by Norbert Juraschitz, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 11th edition, Munich 2013, pp. 322–324, ISBN 978-3-421-04359-7 .

- ↑ a b Helmut Pemsel : Seeherrschaft - A maritime world history from steam navigation to the present , Vol. 2, Koblenz 1994, p. 464.

- ↑ a b c d e Aram Mattioli: Libya, promised land , in: DIE ZEIT, No. 21 (2003)

- ↑ a b c Ferenc Majoros / Bernd Rill: Das Ottmanische Reich 1300–1922 , Augsburg 2002, p. 353f

- ↑ a b Helmut Pemsel: Seeherrschaft - A maritime world history from steam navigation to the present , Vol. 2, Koblenz 1994, p. 465.

- ^ Jean-Claude Gerber: 20 minutes , Zurich 13./14. May 2011: The very first bomb fell on Libya - Italy recently decided to participate in NATO air strikes against Libya. It was there 100 years ago. With a remarkable premiere.

- ↑ War reports and loss statistics, in: International Review of the Entire Armies and Fleets , May 1912, p. 183.

- ^ William Clarence Askew: Europe and Italy's acquisition of Libya 1911-1912 , Durham (North Carolina) 1942, p. 249.

- ↑ Boris Zesarewitsch Urlanis: Balance of the Wars , Berlin 1965, p. 123.

- ^ WI Lenin : The end of the war between Italy and Turkey , in: WI Lenin: Werke , Vol. 18, Berlin 1962, p. 329.

- ↑ Archive link ( Memento from October 9, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Claudia Anna Gazzini: Jihad in Exile: Ahmad al-Sharif as-Sanusi 1918–1933 ( Memento of January 31, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1 MB), pp. 19–25.

- ↑ Aram Mattioli: Libya, promised land , in: DIE ZEIT, No. 21 (2003)

- ↑ Aram Mattioli: Libya, promised land , in: DIE ZEIT, No. 21 (2003)