Submarine war

As submarine warfare (also called "submarine warfare") are fighting for the lake refer to operations where submarines are used to hostile war and cargo ships to sink. The term unrestricted submarine warfare is used when vessels are attacked without warning.

The use of submarines changed over the course of time from a tactical blockade breaker to a strategic means of blocking in the context of a trade war . After the Second World War , the basic operational doctrine changed with the development of missile-carrying nuclear submarines , which, as carriers of nuclear weapons, represent a permanent threat beyond the maritime domain. In contrast to the First and Second World Wars, there was no further development under international law on the use of submarines.

The term is particularly related to the First and Second World Wars. The framework conditions under international law are also important here.

Beginnings

Several hand-propelled submarines were built during the American Civil War in 1864. On February 17, 1864, the CSSHL Hunley of the Confederate States Navy (Southern States) sank the warship USS Housatonic of the Northern States by means of an explosive charge . There were 5 dead on the sunk ship. The Hunley is therefore the first submarine in the world to be destroyed by another ship. However, the submarine was badly damaged by the detonation in the attack on the Housatonic and sank, killing its eight-man crew. The Hunley's mission was to break the blockade of the southern port of Charleston by the northern states.

First World War

The technical development of submarines up to the beginning of the First World War describes a boat that was powered by steam , gasoline, diesel or petroleum machines over water and by battery-powered electric motors under water. The international law doctrines of the cruiser war forced the submarine to conduct surface warfare . As a result, the typical submarine now got guns , torpedoes and an open bridge to observe the sea area. The underwater properties receded, so that a submersible was established that could only move slowly under water due to small battery capacities, but with powerful internal combustion engines quickly over water in order to be able to follow, overtake or overtake fast surface forces and merchant ships.

Due to the doctrines of the cruiser war and the ensuing developments in battleships , the submarine was initially given little importance. It was not until the German Imperial Navy came to the conclusion that the submarine should be used as a trade disruptor. Great Britain with its empire , at that time the leading sea power , wanted to protect its sea routes from submarines. For this purpose, Q-Ships were used, which operated as submarine traps .

Naval warfare

In order to compensate for the unfavorable German-British balance of forces of the naval forces (1: 1.8), the German warfare decided, contrary to the view of Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz , to engage in guerrilla warfare through mines and submarines against Great Britain. A first spectacular success came in the U 9 in the naval battle on September 22, 1914 three British with the sinking battleship of Cressy class within just one hour. In response to the British remote blockade (Shetlands - Norway line), which declared the North Sea a war zone on November 2, 1914, Germany declared the waters around Great Britain a war zone on February 4, 1915.

On February 22, 1915, the German Reich government ordered unrestricted submarine warfare against merchant ships of warring and neutral states within these waters.

On May 13, 1915, the submarine war was restricted after U 20 sank the British passenger steamer RMS Lusitania, which was loaded with 10 tons of weapons . Since 114 to 128 US citizens had died, the United States protested against the blockade in Great Britain and threatened Germany with entering the war after further sharp protest notes.

On February 29, 1916, the German Admiralty intensified the submarine war by sinking armed merchant ships without warning. Tirpitz and Falkenhayn were unable to assert themselves with their demand for an unrestricted submarine war against Bethmann-Hollweg and the Kaiser . Relentlessly, he urged that his positions be implemented. Thereupon Tirpitz was forced to resign as State Secretary of the Reichsmarinamt, which he did with his move on March 17, 1916.

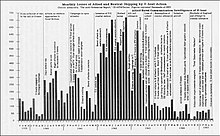

After the Skagerrak battle , which Germany had won tactically but lost strategically, the German admiralty believed that it could defeat Great Britain within six months through unrestricted submarine warfare. Against the opinion of the political leadership, which feared that the USA would enter the war, Germany declared unrestricted submarine war again on February 1, 1917. By December 31, 1917, 6.141 million GRT of allied shipping space and 1.127 million GRT of neutral shipping space had been sunk. Unrestricted submarine warfare was used by the United States to enter the war on April 6, 1917. In spite of the ongoing sinking of 600,000 GRT per month, the supply from the USA to Great Britain could no longer be permanently disrupted.

The "unrestricted submarine war" was discontinued in the course of the exchange of notes with President Woodrow Wilson on the basis of his 14-point speech on October 21, 1918.

Submarine use

The importance of the weapon became generally apparent when U 9 sank the British armored cruisers Aboukir , Cressy and Hogue on September 22, 1914 . 1,467 men died, 837 survived.

At the beginning of the war there was no targeted deployment doctrine for submarines. Both sides used them for patrols in the enemy-controlled sea area to fight enemy warships. Various encounters of the surface forces quickly led the German Admiralty to the idea of using the submarines as trade disruptors against Great Britain.

In a trade war under price law , the German submarines risked being sunk by armed freighters or British submarine traps , as the price order stipulated that merchant ships should not be sunk without warning. The ships were to be stopped by signals, if necessary by a shot in front of the bow . After reviewing the freight documents and, if the charge by a set about boarding party was then to decide whether in fact a pinch existed or trading rider clear ahead was granted. In the event of a sinking, the castaways had to be picked up and taken care of. These regulations originated historically from wars with ships of the line and cruisers. They couldn't match warfare with small, vulnerable submarines.

Although Great Britain went to great lengths to combat the submarines, including with Q-ships (merchant ships with hidden armaments, sometimes even sailing under a neutral flag), ship losses rose steadily. Only in 1918 did the introduction of the convoy system mean that the individually operating submarines were only successful against the merchant ships escorted by numerous escort ships in an underwater attack, which, due to the submarine's low underwater speed, only had a chance of success if the convoy was on a favorable course.

The main weapon of the submarines in the First World War were the deck guns , which were used in the war to stop the ships according to the price order, which, if they were allowed to be sunk, were sunk by explosive charges or by floods. They used torpedoes almost exclusively for surprise attacks, during which the boat remained submerged. In addition, the German submarines laid thousands of mines , especially from bases in occupied Flanders. The submarines were so successful in the Canal that the Royal Navy had to use strong forces, including monitors , to bombard the submarine bases on the Belgian coast. Despite numerous attacks, such as the attack on Zeebrugge and Ostend on 22./23. April 1918, it was not possible to block these bases until the end of the war.

The greatest successes with minimal losses achieved German submarines in the Mediterranean , against both war and merchant ships. Although the price order was mostly used there, the sinking results, based on the number of submarines used, were greater than in World War II . Several hundred ships were sunk in these waters alone by U 34 , U 35 , U 38 and U 39 . The most successful commanders ( de la Perière , Forstmann , Valentiner , Steinbrinck ) sank considerably more tonnage than their successors in the Kriegsmarine , which can be attributed to the considerably improved techniques of anti-submarine combat in World War II. The last commander of the German submarines in the Mediterranean was Kurt Graßhoff .

The Austrian Navy also owned and used submarines. After three prototypes, the decision was made to build submarines to protect the war ports and the Adriatic.

On the German side, 3274 missions of 320 boats were carried out, during which they sank 6394 civilian ships with a total of 11,948,792 GRT (plus 100 warships with 366,249 ts). According to Admiral Jellicoe , in November 1917 the 178 submarines that were active at the time were used:

- 277 destroyers

- 30 gunboats

- 44 P boats

- 338 motor boats

- 65 submarines

- 68 coasters

- 49 steam yachts

- 849 fish steamer

- 687 Drifter (net fisherman)

- 24 minesweepers

- 50 airships

- 194 aircraft

- 77 submarine traps

In the submarine war, 5,132 men with submarine weapons died on the German side, 200 submarines sank or are considered missing.

As a result of the provisions of the armistice of November 11, 1918 , all 170 submarines of the German Imperial Navy were delivered to Great Britain and occasionally to other Entente states in the following weeks . The majority of these boats were scrapped. There were no self-sinkings like the deep sea fleet in Scapa Flow in 1919 or like many submarines after the Second World War , but a number of boats sank on the transfer trips for unknown reasons.

Between the wars 1918–1939

Effects of the Versailles Treaty

Articles 181 and 190 of the Versailles Treaty stipulated strict conditions and restrictions for Germany's navy:

"After a period of two months from the entry into force of the present contract, the German naval forces in service may not exceed: 6 battleships of the Germany or Lorraine class, 6 small cruisers, 12 destroyers, 12 torpedo boats or an equal number of Ships built to replace them, as provided for in Article 190. Submarines may not be included. All other warships must be decommissioned or used for commercial purposes unless the present treaty provides otherwise. "

"It is forbidden for Germany to build or acquire any warships, except to replace the units in service in accordance with Article 181 of the present Treaty [...]."

As early as 1922, the Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw, an engineering office for shipbuilding under German control, was opened in The Hague in the Netherlands in order to undermine the provisions of the contract. The reintroduction was achieved through the construction and testing of submarines that were officially built on behalf of other countries - for example the Finnish submarine Vesikko , which was the forerunner of the Type II submarine of the Kriegsmarine - and the exchange of members of the Navy with other navies the submarine weapon being prepared in Germany.

With the establishment of the League of Nations in 1920, which Germany joined in 1926, and the ratification of the London Agreement by Germany in 1935, international legal provisions for conducting a submarine war were again defined, which essentially corresponded to the conditions before the First World War, as Great Britain after the experience of First World War had recognized that sea connections to be protected were endangered by a massive use of submarines. Consequently, a submarine war had to be prevented politically and militarily. The above-mentioned convoy concept together with ASDIC led to the opinion in many navies that the submarine was outdated as a weapon and consequently led to the Z-Plan in Germany in the update of the battleship concepts of the First World War. A few naval soldiers, however, took a different view and developed strategies and concepts for the use of submarines ( Nimitz , Dönitz ).

From the naval agreement with Great Britain to the outbreak of war

The German-British naval agreement of 1935 allowed the navy to own 45% of the British navy's submarines (max. 72 boats). In the same year the first submarines of the Kriegsmarine were put into service and used in the Spanish Civil War the following year . During this mission, the German submarine U 34 sank the republican submarine C-3 .

In January 1939, the FdU Dönitz wrote a memorandum to the Naval War Command in which it demanded 300 submarines in order to be able to do "decisive things against England". With this he entered forbidden territory, because England as an opponent of the war was politically not expected by the German leadership after Chamberlain's policy of appeasement. Accordingly, everything that described a war with Great Britain was ignored.

Second World War

At the beginning of the Second World War , the Navy had 57 submarines (also known as "Gray Wolves"), but only 39 of them were suitable for use in the Atlantic. According to the rule of thirds (one third in combat, one third on the march in and out, one third in overhaul and equipment), only about 20 boats were in use around Great Britain.

The leader of the submarines , Dönitz, hoped that the pack tactics, together with radio methods that were not available during the First World War, would create a new type and form of submarine warfare, which was to be conducted primarily against convoy trains. The basic concept was to use an equally massed pack of submarines on gatherings of ships with numerous, concentrated security ( convoy ) . A submarine standing in the front should not attack immediately if it encountered a convoy, but rather wait until boats standing nearby had been brought up by the central command (Dönitz), which the boat in contact with the Sending of direction finders has been made easier. When a large pack had formed, the central command released the attack on the convoy. For this he called for the 'Atlantic boat' with long ranges. The Type VII fulfilled these expectations and became the “workhorse” of the German submarine war.

The United States followed a similar concept. Without central guidance, the American boats operated in small groups with mostly three boats, which were called "Wolfpacks".

Submarines proved to be an effective weapon in all theaters of war in the world. Both the Kriegsmarine and later the US Navy used submarines primarily in the trade war to bring the opponent's logistics to a standstill. After the USA entered the war, the German submarine command changed the war objective away from the blockade of Great Britain towards a strategy of sinking more shipping space than the enemy could produce. So the locations were of secondary importance and German submarines fought in all the world's oceans, only limited by technical and supply options. Due to technical advances made by the Allies such as radar, HF / DF radio direction finding , the deciphering of the Enigma encryption, the formation of escort groups (convoy) and material superiority while at the same time overstressing the resources of the Axis powers, the German submarine war from May 1943 onwards became a historical one To see sight as lost. When allied developments became known, the Axis Powers began to develop a boost that came too late to turn the war, but led to strategic changes in all navies, air forces and armies.

The beginning of the war and the prize order

When the war began, the belligerent powers Great Britain, France and Germany began where they had left off in World War I. The German submarines had orders to adhere to the price order in the trade war , according to which only merchant ships of warring nations or with cargo from or for warring nations were allowed to be sunk and only if the safety of the crew of the merchant ship was ensured. Exceptions were made for armed merchant ships and those escorted by warships. In particular, this order was intended to avoid going to war with the United States, which had happened in World War I through unrestricted submarine warfare. Nevertheless, the Athenia, which left during peacetime, was probably the first ship to be sunk by mistake. For fear of a reaction from the United States, the log of the sinking U-30 was forged and Nazi propaganda tried to portray the sinking as a provocation from Great Britain. The Allied powers began to arm their merchant ships and organize convoys.

On September 14, 1939, U 39 (Kptlt. Glattes) attacked the Ark Royal ; the torpedo detonated prematurely, although the attack was only 800 m away (for the technical problems of the torpedo see torpedo crisis ). U 39 was then sunk by the British security destroyers Faulknor , Firedrake and Foxhound - the first German submarine loss in World War II and at the same time the first successful use of the British SONAR underwater location device ( ASDIC ).

When used against warships, the submarines were not restricted by orders. Günther Prien penetrated the British Scapa Flow base with U 47 in October 1939 and sank the battleship Royal Oak there . The British aircraft carrier Courageous was sunk by U 29 in September 1939. These successes against British capital ships in the early days of the Second World War also convinced the skeptics in the leadership of the Navy of the military value of the submarines. As a result, the Z-Plan was revised in favor of a submarine construction program, but with construction times of twenty-one months and a rate of twenty to twenty-five boats per month from August 1941.

April to June 1940 - Battle for Norway

At the beginning of 1940 it became apparent, among other things through the Altmark incident , that the neutrality of Norway was not respected by Great Britain. The OKM therefore ordered Dönitz , the leader of the submarines, to order all available boats, even the school boats of the training flotillas, to protect the flanks of the German fleet associations of the Weser Exercise company and to set them on the approach routes of the British fleet between Scotland and Norway. At the same time, the Royal Navy ordered their submarines off the Norwegian coast to intercept the German units between their bases and Norway. While the Weser Exercise enterprise was a German success as a result, as Norway was conquered and remained occupied until the end of the war, the result at sea was more advantageous for the Allies. In addition to the loss of the heavy cruiser Blücher by Norwegian coastal batteries, the light cruiser Königsberg by British aircraft and ten destroyers in Narvik by the British fleet, the Navy also suffered losses from Allied submarines. The cruisers Lützow and Karlsruhe were badly damaged by torpedoes from the British submarines Spearfish and Truant , and the artillery training ship Brummer sunk by the Sterlet . In addition, several supply freighters were destroyed.

During the same period, the German submarines had optimal shooting positions against British ships on numerous occasions, but could hardly achieve any success. On three occasions U 48 alone came into the best position for torpedo attacks against British warships without causing damage with the torpedoes that were shot. One of the many causes of these failures was an incorrect depth control of the torpedoes by creeping air (increase in the pressure in the torpedoes during the diving phases), which meant that the magnetos of the torpedoes no longer triggered safely ( torpedo crisis ). After switching to impact fuses, they also proved to be unreliable. Despite the massing of enemy ships and good shooting positions, no effective torpedo hits could be achieved in Norwegian waters with one exception.

The battle in the Atlantic

First phase: June 1940 to December 1940

After the successful campaign in the west , in 1940, temporary submarine bases were built in Brest and on the Biscay coast in Lorient , Saint-Nazaire and La Rochelle ( submarine repair yard Brest , submarine bunker in Lorient , in St-Nazaire and in La Rochelle ). With the help of forced labor , these facilities were expanded, bunkers were to be built for several submarines each, which could also withstand air attacks.

Thanks to these new ports on the Bay of Biscay, the submarines were able to reach the operational areas on the western access routes to the British Isles much faster . The Allied convoys were poorly secured due to a lack of escort ships , which were in the repair yards due to the failed British invasion of Norway. This period was described by the Navy as the "first happy time" of the submarines, in which numerous Allied ships could be sunk with relatively few losses of their own. The most successful were the commanders Otto Kretschmer ( U 99 ), Günther Prien ( U 47 ) and Joachim Schepke ( U 100 ), who were celebrated as heroes by German propaganda.

On August 17, 1940, Germany responded to the British blockade by declaring the counter-blockade. The blockade area coincided almost exactly with the zone which US President Roosevelt had banned American ships from entering since November 4, 1939. The submarines were thus given the right to sink within this area without warning, with the exception of hospital ships and neutrals who had to use certain contractually agreed routes such as the " Schwedenweg ".

During this time around 4.5 million GRT of Allied shipping space were sunk.

Second phase: January 1941 to December 1941

In the winter of 1940/41, bad weather made surface attacks by the submarines difficult. The British began to use radars and shortwave direction finding on their escort ships and the number of available escorts had risen sharply due to an increased construction program.

In March 1941, the Navy lost three "aces" in just one attack, namely Günther Prien and Joachim Schepke through death and Otto Kretschmer through capture. From the summer of 1941, the pack tactics were increasingly used , with submarines as "wolf packs" locating convoys and attacking them in a coordinated manner. The escorts, often outnumbered, usually tried to force the first submarine they detected, giving the remaining pack members the opportunity to attack the merchant ships.

Against the will of the commander of the submarines Karl Dönitz , submarines were also sent to the Mediterranean to interrupt the Allied supplies to North Africa (where the Africa campaign took place from September 1940 to May 1943 ).

On June 20, 1941, U 203 under commandant Rolf Mützelburg reported the sighting of the US battleship USS Texas in the blockade area. In this situation, the German command issued the order to the submarines not to attack security vehicles any more. In July, the US President Roosevelt gave the US Navy the order to attack German submarines and repeated this order in September 1941. On September 4, 1941, U 652 (Commander: Fraatz) was 180 nautical miles southwest of Reykjavík from the US destroyer USS Greer attacked with depth charges and shot two torpedoes in defense. The defensive measure was expressly approved by the German leadership. Similar attacks were repeated increasingly. The United States went into open hostilities against German U-boats without a declared state of war.

During this time, the submarines sank around 3 million GRT of the opposing shipping space.

Advances in anti-submarine defense

The deciphering of the naval codes by British code breakers (including Alan Turing in the lead ) brought about a turning point in the Atlantic War. As early as 1934, Polish mathematicians had achieved partial results by interconnecting six Enigma encryption machines, which were later made available to the British radio intelligence agency in Bletchley Park (Government Code and Cypher School, GC&CS). Under the guidance of Turing, an electromechanical deciphering machine, the Turing bomb , was built. The German naval key was finally deciphered in May 1941. This was made possible by the fact that the Enigma machine cylinders and code books needed for deciphering the naval key could be obtained.

The greatest progress for the GC&CS was brought about by the capture of U 110 on May 9, 1941 by the British destroyer HMS Bulldog . The British Admiralty lost the entire " M key " including the two rollers "VI" and "VII" used only by the Navy, the "manual for radio in domestic waters", the crucial " double-letter exchange tables ", the special key for officers, key documents for the reserve manual procedure (RHV) and the map with the marine squares for the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean in your hands. From now on, the British could read the entire radio traffic between Dönitz and the submarines. However, a time of 40 hours was still required to decipher the radio messages. From November 1941 the British read the radio traffic every day.

A shorter interruption of just under a month occurred when the High Command of the Navy introduced a new key network called “Triton” only for the Atlantic submarines on October 5, 1941 . A longer and more painful for the British interruption (blackout) of more than ten months there was then, as the Enigma to a fourth roller to the February 1, 1942 Enigma M4 has been expanded. It was not until December 12, 1942, that Triton could finally be deciphered again after the British sailors Tony Fasson , Colin Grazier and Tommy Brown from HMS Petard had managed to board U 559 on October 30, 1942 , and top secret code books such as Short signal booklet and weather short key to retrieve from the sinking submarine. By deciphering the German radio traffic, it was possible to divert convoy trains around the positions of German submarines and to search sea areas specifically for submarines by hunter killer groups (task forces of destroyers and escort aircraft carriers ).

From 1943 onwards, the Allies also had shortwave direction finding devices known as “ HF / DF ”, which for the first time enabled radio-controlled submarines to be located from a single ship. Hunter killer groups then headed for the boat under surveillance, attempted to destroy it with depth charges or to force it to surface due to lack of oxygen or exhausted batteries, so that it could be destroyed on the surface.

Another defensive measure against submarines was the use of escort aircraft carriers as escorts for merchant ship convoys. Initially, rather provisional measures were taken in the form of CAM (ships with aircraft catapults) and MAC ships (merchant ships with a makeshift flight deck over the loading areas), before the American Bogue class launched smaller aircraft carriers specifically for submarine hunts in 1942 were built. The aircraft operating from the escort aircraft carriers were used by the convoy commodores for reconnaissance as well as for combating sighted submarines. Aircraft had air-surface radar from 1940, which was continuously improved in the course of the war.

From mid-1942, Allied aircraft had powerful headlights (" Leigh light ") for night attacks , which enabled effective night attacks on submarines, which until then had been safe from air raids at night. A submarine spotted by radar and illuminated by a Leigh Light usually had no time to dive before the attack. As a further means of location, Allied aircraft for fighting submarines from the middle of the war had magnetic anomaly detectors (MAD), which made it possible to locate submerged submarines, but were still often faulty. As an improvement, sonar buoys were developed, which reduced the error rate of MAD locations. MAD and sonar buoys are still used today in an improved form in anti-submarine combat. Due to the increased danger to the submarines from the air, the anti-aircraft armament of the boats was reinforced and radar detectors such as the Metox device were retrofitted, although their development could not keep up with the improvements of the Allied radar. When the Western Allied bombers H2S - centimeter waves - radars were, the Germans developed the radar detector Naxos . The acoustic target-seeking torpedo “Wren” developed by the German Navy was unreliable and could easily be deflected with the “Foxer” jamming system that the Allies had developed as a result.

Third phase: January 1942 to December 1942

On December 11, 1941, four days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor , Hitler declared war on the United States. Thereupon Admiral Dönitz changed his war goal: no longer the blockade of England, but the sinking of enemy ship space (tonnage war) and the place with the greatest chances of sinking were given priority. Long-range Type IX submarines were set off for Operation Paukenschlag in America, where they arrived in the first days of January 1942. The initially poorly organized US coastal defense faced the attacks on merchant shipping helplessly (“second happy time”). During this time, more ships were sunk with the submarine cannons than ever before. When the defense was strengthened in the spring, the German submarines expanded their operational area into the Caribbean and the South Atlantic. The shorter-reaching Type VII boats were operating in packs in the North Atlantic at the same time and were thus able to maintain the pressure on the convoys. There were several large convoy battles during the year.

Through the use of supply submarines (so-called milk cows ), which supplied fuel oil and other operating materials, the smaller Type VII boats were soon able to operate off the American coast.

The number of operational German submarines had now risen further, at the end of 1942 it was about 210. In total, over 8 million GRT of ship space was sunk in 1942, making this year the most successful in the tonnage war of submarines.

Fourth phase: January to May 1943

The year 1943 was the turning point in the submarine war. At the beginning of the year, the German submarines achieved their last major success when, in mid-March 1943, three wolf packs with a total of 43 submarines south of Greenland sank 22 ships with 142,000 tons from the convoys SC 122 and HX 229 and another 9 ships with 45,000 Tons torpedoed. They also benefited from the fact that there was still a gap in Allied aerial surveillance in the area.

After the Allies closed the gap south of Greenland in the air surveillance of the Atlantic by stationing long-range bombers on Greenland and Iceland , the entire North Atlantic was under Allied air sovereignty . Added to this was the increased security of the convoys. The British commander in chief of the so-called Western Approaches , Admiral Max Horton , who had been in office since November 1942 and was himself a successful submarine commander in World War I, introduced a series of tactical changes in the security of the convoy, which meant that German submarines were increasingly being hunted from hunters to hunted did. In May 1943 alone, 43 German submarines were sunk. Dönitz then temporarily stopped the submarine warfare against convoys and had most of the submarines recalled from the pack operations.

Fifth phase: June 1943 to May 1945

Despite the realization that the submarine war in the Atlantic offered little chance of success for the German submarines, more boats were sent out until the end of the war to take large numbers of ships, aircraft and soldiers of the Allies to combat submarines to tie. When the bases in France were lost after the invasion of northern France, the submarines were relocated to Norway. The Navy reacted to the improved hunting techniques of the Allies with its own technical improvements:

The snorkel , a pre-war Dutch development that initially did not convince the navy, was retrofitted on numerous boats or installed before the boat was completed. In the types XXI and XXIII it was integrated into the tower as a retractable telescopic mast . On the older guys, the snorkeling mast was on the starboard side of the tower and was laid down on the deck when not in use. It made it possible to ventilate the boat while underwater and / or drive the diesel engines. The batteries could be charged or you could do without using the charged batteries and still drive.

Other German innovations were target-seeking torpedoes (see Zaunkönig (torpedo) ), sonar disruptors that could be ejected from the torpedo tubes ( bold ), sonar-absorbing hull and snorkel coatings, active and passive underwater and surface detection devices (called radio measuring devices at that time ). The development of new types of boats (e.g. Type XXI and Type XXIII ) was also pushed. Type XXI could be built faster thanks to the sectional construction. Alternative drive concepts were tested ( Type XVII with Walter turbine ). Of these newly developed boat classes, however, only a few Type XXIII boats were successful; most of the new boats were still in training at the end of the war.

The tonnage war , however, was decided in retrospect: in 1943 a total of 287 German submarines were lost, almost twice as many as added together in the previous three years, while the sunk tonnage decreased: in 1943 only 3.5 million GRT were sunk, far less when the Allies put them back into service through building programs for standardized ships ( Liberty freighters ). This development continued until the end of the war: in 1944 and 1945 only 1.5 million GRT were sunk. In contrast, there were 241 submarines lost in 1944 and a further 153 submarines from January to May 1945.

Submarines of other nations in the Atlantic

Italian submarines in the Atlantic

In June 1940 the Italian Navy had one of the largest submarine fleets in the world with over 100 submarines. Because of some technical deficiencies, a number of boats in the Mediterranean were only used for reconnaissance and transport purposes, while others were sent to the heavily secured convoys of Malta. Shortly after the Italian entry into the war, a more promising deployment in the Atlantic was planned for the large Italian long-range submarines. As early as the summer of 1940, the first Italian submarines were operating in the Atlantic, but always had to risk the risky breakthrough through the Strait of Gibraltar . Shortly afterwards, the Italian Atlantic boats were stationed in a newly established Italian submarine base with the code name BETASOM in occupied Bordeaux . Up to 1941, up to 32 Italian boats were operating in the North Atlantic, but sunk about 70% fewer than their German counterparts during this time. Due to coordination problems, the focus of the Italian submarines was relocated to the Central and South Atlantic, some boats also operated in the Indian Ocean. From 1941 to 1943 a total of 32 Italian submarines were used in the Atlantic. 16 of them were lost to sinking and 6 to surrender. In total, they sank 106 ships with 564,472 GRT, of which the Da Vinci alone sank 17 ships with 120,243 GRT.

Submarines in the service of the Allies

In contrast to the German submarines, which had been developed for use in the trade war on the high seas, most of the Allied submarines had only a short range. They were mainly used to monitor ports and naval bases under German control. In addition to the British submarines, this task was also taken over by French boats like the Doris , Dutch boats like the O 21 and even Polish boats like ORP Wilk , which had withdrawn to English bases after the occupations of their home countries. In the later course of the war, British submarines were also given to allied navies, so that Norwegian submarine crews also intervened in the war.

The militarily most important action by Allied submarines in the Atlantic were the measures taken during the occupation of Norway . Allied submarines inflicted heavy losses on the surface units of the Kriegsmarine and sank the light cruiser Karlsruhe , the artillery training ship Brummer and a number of merchant ships and damaged the ironclad Germany .

Allied submarines were also used as escorts and to lay sea mines . The most successful allied submarine of the Second World War was the French mine-laying submarine Rubis , which was mainly used off the Norwegian coast.

After the French surrender, the submarines of Great Britain and France also fought against each other for a time. Above all with the boats left by the Germany-friendly Vichy government , there were repeated battles, while other naval units united under the flag of Free France or joined the Royal Navy. The naval battle of September 20-25, 1940, known as the ' Dakar Affair ', is symptomatic of the relationship between the Vichy regime and Great Britain .

In this operation, known as Operation Menace , British ships shelled the port of Dakar . The background to this operation was that the French armed forces in West Africa had sided with the Vichy government. The warships lying in Dakar thus posed a threat to the Allied lines of communication in the Atlantic, so that the Allies decided to launch a preventive strike. In the course of the fighting, the Bévéziers submarine torpedoed the battleship HMS Resolution . The French submarine Ajax was sunk by the destroyer HMS Fortune .

The submarines in the Mediterranean

Against Dönitz's opinion, the naval leadership succeeded in moving submarines from the tonnage war in the Atlantic to the Mediterranean in autumn 1941 at Hitler's request. The background to this was the campaign in Africa , in which German troops had been involved since the beginning of 1941, whose supplies across the Mediterranean were in danger. Although Italy had considerably more submarines than Germany at the start of the war, the Regia Marina (= Royal Navy) was not able to achieve naval supremacy in the Mediterranean.

In the Mediterranean there were fewer targets for the German submarines, apart from the British convoys to supply Malta ; In terms of marine strategy, the relocation of the submarines made little sense. Although some warships, including the aircraft carriers HMS Ark Royal and HMS Eagle as well as the battleship HMS Barham , were sunk for propaganda purposes , the number of submarines sunk during operations in the Mediterranean Sea or when trying to break through the Strait of Gibraltar were sunk , was out of proportion to the sinking of merchant space. On the one hand, the German submarines sank around 40 warships and 140 civilian ships in the Mediterranean. On the other hand, around 65 German submarines were lost in the Mediterranean. The entire crew fell on 24 submarines.

In contrast, British submarines operated successfully from their bases in Malta, Gibraltar and Alexandria against the ships of the Axis powers that were supposed to transport supplies to the North African theater of war. A large part of the supplies for the German-Italian Africa Army was sunk thanks to information from the British Ultra Secret . This is believed to be one of the causes of the Allied victory in North Africa.

Submarine war in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea was the scene of submarine warfare only at the beginning and end of the war, as Allied naval forces would only have been able to access the Baltic Sea through the Skagerrak and Kattegat , which were under German control after the occupation of Denmark and Norway. The sea war in the heavily mined Baltic Sea was therefore only fought between neighboring countries .

German submarines were involved in the attack on Poland in 1939 and participated in the blockade of the ports. They did not achieve any sinking. Of the five Polish submarines, three escaped to neutral Sweden, where they were interned for the remainder of the war. Wilk managed to evacuate to England, Orzel was first interned in Reval , but then broke out for fear of being captured by a Soviet occupation of neutral Estonia after all and made his way to England without nautical charts.

Since the entire Baltic coast with the exception of the enclosed Leningrad and neutral Sweden was occupied by the Axis powers Germany and Finland by the end of 1941 , there were hardly any major fighting in the Baltic Sea between 1941 and 1944. The main activities of German and Finnish submarines were limited to training trips and the laying of mine barriers in the Gulf of Finland or off Leningrad and Kronstadt , as the naval command feared an attempt by the Baltic fleet to break out of Leningrad.

Only when further Baltic ports became free again towards the end of the war and the mine barriers could be bypassed did Soviet submarines intervene in the war, where they threatened German shipments to and from the East Prussian basin. In doing so, they caused three of the most devastating shipping disasters of all time: On January 30, 1945, the S-13 (С-13) sank the Wilhelm Gustloff , killing more than 9,000 people. On February 10, S-13 sank the Steuben , killing 3,600 people. On April 16, the Goya fell victim to the Soviet submarine L-3 (Л-3) . This sinking cost over 6,000 lives.

Submarines in the Black Sea

After Romania entered the war on the Axis Powers' side, six German submarines ( U 9 , U 18 , U 19 , U 20 , U 23 and U 24 ) of type II B became the 30th submarine flotilla to Constanța on the Black Sea relocated to aid German attack on Crimea . From their previous locations as school boats in the Baltic Sea, the boats first made their way to the Black Sea on the Elbe to Dresden and then on land, mostly on the Reichsautobahn to the Danube near Ingolstadt . They then continued on the Danube to the Black Sea. For this purpose, the submarines were partly dismantled and tilted on their side in order to be able to pass low bridges. For the river transport the lying boats were dragged surrounded by floating bodies. After reaching the Danube, the reconstruction began in Vienna. The final equipment was then carried out in the Black Sea.

In the Black Sea, the boats attacked the Soviet army's supply lines across the sea. According to official information, a total of 26 ships with 45,426 gross tons were sunk. The use of German submarines in the Black Sea ended on September 10, 1944, when the last three boats sank near the Turkish coast after the loss of the base in Constan selbsta. The U 18 and U 24 had previously been sunk in August 1944 due to wear and tear and damage, and the U 9 was destroyed by Russian aerial bombs in the same month.

In addition to the German submarines, the three submarines of the Romanian fleet ( Delfinul , Marsuinul and Rechinul ) also operated in the Black Sea, but with less success. Small submarines made in Italy were also used, under both Italian and Romanian leadership. The Italian small weapons mostly operated together with speedboats.

The submarines of the Soviet Black Sea Fleet operated against the shipping traffic of the Axis powers. The most famous event of the submarine war in the Black Sea was the sinking of the Panamanian flagged Bulgarian steamer Struma on February 24, 1942 by the Russian submarine Scht-213 (Щ-213) , in which 768 Jewish refugees died came.

The monsoon boats

The monsoon boats (East Asia boats ) were German long-range submarines, mostly of the type IX D2, which from 1943 operated from a base in Penang in what is now Malaysia , mainly in the Indian Ocean , but also in the Pacific. The reason for this was the wish of the Japanese allies to be able to study German submarine technology. In addition, Doenitz hoped to tie up further Allied warships through successes against the still unsecured merchant shipping in these waters. A final factor was that the submarines were able to carry rare raw materials, technologies and passengers on the transfer to and from the Far East. However, this transfer exceeded the maximum range of the submarines, so that complicated preparations had to be made in order to be able to supply the boats with supplies from other submarines or tankers on the way.

The first boat to reach Penang was the U 511 , called Marco Polo I , which was handed over to Japan and re-entered service in the Imperial Japanese Navy as the RO-500 . The crew of U 511 formed the staff of the base in Penang and served as replacement personnel for the later monsoon boats. For reasons of secrecy, the German navy personnel in Penang did not wear uniforms, but were given civilian clothes. They wore black-white-red cockades on their collars to make them clear to the Japanese authorities. Of the original eleven monsoon boats that left Europe in the first week of July, five reached the Indian Ocean in September 1943, right after the annual monsoon rains . The relocation was made much more difficult because the supply submarines called “ dairy cows ”, which were supposed to take over the supply, were sunk by the Allies or had to return to the port, so that two of the originally eleven boats of the first wave take on the role of supply boats had to. Four other boats have already been sunk in the Atlantic. The five boats that eventually reached the Indian Ocean sank several Allied merchant ships there.

Of the second wave, which included four boats, only U 510 reached the Far East. The three remaining boats have already been sunk in the South Atlantic as the Allies had reacted to the increased threat. This boat also achieved success in the Indian Ocean. Due to a lack of torpedo it was then decided to order three of the boats of the first wave back to France. Two of these reached the bases in France again. The third boat had to return to Penang as it had to deliver fuel to one of the other boats due to the sinking of a supply tanker.

Despite the losses, the use of the boats seemed to outweigh the Far East, so more boats were sent to this area. These included two of the Type VII F torpedo transporters, one of which reached Penang, boats that had been converted into pure transport boats, as well as other boats for war patrols. The activity of the German submarines in the Pacific reached its peak in July and August 1944. However, very few of the boats reached bases in France again. From Penang some enemy voyages were also undertaken, which ended again in Penang. The most striking is the patrol of U 862 , which was the only German submarine to penetrate the Pacific and sink an American merchant ship off the east coast of Australia.

One of these later monsoon boats was also U 852 , whose captain, Kapitänleutnant Heinz-Wilhelm Eck , tried to sink the freighter's life rafts with machine gun fire and hand grenades after the sinking of the Greek freighter Peleus , killing several survivors of the sinking. Eck and two fellow officers were convicted as war criminals and executed for this act after the war . See also: Peleus incident

Another focus of the mission of the Monsun group was the transport of goods such as important raw materials, e.g. B. tin or tungsten, but also quinine and opium, as basic materials for drugs. For this purpose, Italian submarines were converted into transport submarines in the so-called “Aquila” program. The transport of material between Germany and Japan was so important that in April 1945 U 234 left a base in Norway for Japan with a cargo of uranium oxide , a dismantled aircraft ( Me 262 ), German technicians and two Japanese officers. The boat surrendered in an American port after the end of the war. Two German submarines with a total of 272 t of goods from Penang reached German ports in the first half of 1945, four more arrived after the end of the war.

A total of 41 Navy boats operated in East Asian waters from 1943 onwards.

After the surrender

On May 4, 1945 Dönitz ordered the boats at sea to stop fighting. Due to the rainbow order that had already existed, but was canceled by Dönitz on the evening of May 4th, 216 (other source: 232) of the 376 remaining boats sank themselves. The Allies captured 154 boats, some of which they used for research purposes or as Compensation for losses assumed. 115 were sunk in the Atlantic as part of Operation Deadlight . The remaining so-called monsoon boats were taken over by Japanese crews.

The commanders of two submarines, U 530 and U 977 , decided to capitulate in neutral Argentina . Most of them crossed the Atlantic by diving and entered the Río de la Plata on July 10, 1945 (U 530) and August 17, 1945 (U 977) .

losses

In the U-boat war of the Kriegsmarine, a total of 863 of the 1,162 boats built were used in combat. 784 boats were lost. Over 30,000 of the over 40,000 submarine drivers died. More than 30,000 people died on board the 2,882 merchant ships and 175 warships sunk by German submarines.

Lothar-Günther Buchheim , who himself participated in enemy voyages as a war correspondent on board U 96 , later commented on the losses:

“The submarines were called 'iron coffins'. What was called the 'blood toll' at the time, i.e. the loss rate, was higher among the submarine men than with any other weapon. Of the 40,000 submarine men, 30,000 remained in the Atlantic. Many of them weren't even men - in reality they were half children: the entire submarine orlog was a giant children's crusade. We had 16-year-olds on board, towards the end of the war there were 19-year-old chief engineers and 20-year-old commanders, prepared in a kind of rapid incubation process to be promoted from life to death in one of the most terrible ways. I have always resisted the death reports of submariners saying they had fallen. They have flooded, drowned like excess cats in a poke. "

The Battle of the Pacific

During the Pacific War , both Japan and the United States had significant submarine fleets, as well as a number of British and Dutch submarines.

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Japanese submarines were characterized by a large variety of types, but were not particularly modern, as the Japanese Navy placed more emphasis on surface ships. In addition to micro-submarines that were carried by other submarines close to a target, and submarine aircraft carriers, the Japanese Navy had both fleet and transport submarines. Japanese submarines were used, true to Japanese operational doctrine, mainly against warships and therefore did not achieve high sinking rates.

The special naming and categorization of submarines of different sizes is fundamentally striking. Large Fleet submarines were given a term with I began. Medium types were marked with Ro . Finally, there were also small submarines for special operations, which were given an identification with Ha and in some cases could be transported by large I-boats. In addition, the early efforts of the Japanese Navy to build special submarines for the transport of seaplanes are noteworthy . Most recently, the Japanese navy and thus also the submarines with the Type 95 had the most advanced torpedo in the world at the time.

One of the first submarine operations of the war was an attempt to support the attack on Pearl Harbor with small submarines. However, all boats were lost. Subsequently, submarines supported the Japanese invasions on numerous islands in the Pacific and in the Malay archipelago by attacking transport ships used for evacuation, laying mine barriers and reconnaissance trips, sometimes using seaplanes.

Japanese submarines hardly played a role in the great sea and air battles of the Pacific War. Submarines were hardly involved in the Battle of Midway ; only the already damaged aircraft carrier USS Yorktown could be sunk together with a destroyer lying lengthways to help. In the vicinity of the Battle of Guadalcanal , the submarines sank the aircraft carrier USS Wasp , the destroyer USS O'Brien and the battleship USS North Carolina was damaged . Such incidents remained the exception; more often the submarines carried out trade wars, special operations, reconnaissance and transport trips. The area of operation covers the entire Indian Ocean and the Pacific from Australia to the Aleutian Islands . Individual Japanese submarines broke through into the Atlantic and operated from the German bases in western France. Notable but ultimately unsuccessful special operations include attacks on the ports of Sydney in Australia and Diego Suarez in Madagascar in the summer of 1942.

As on the German side, the number of sunk Japanese submarines rose sharply from 1943 onwards, as the same new technologies and tactics of submarine hunting were used there as in the Atlantic. The success of an American submarine group around the destroyer escort USS England , which killed six Japanese submarines within thirteen days in May 1944, is indicative of the defeat of the Japanese submarine fleet . Instead of constant new developments, the Navy initially pushed the development of the Kaiten called Kamikaze torpedoes. It was not until the last year of the war that new types of submarines such as the Sen-Taka class were developed, which was similar in concept to the German submarine class XXI . However, this type was no longer used. At the end of the war, the Navy had lost a total of 127 submarines.

The sinking of the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis on July 30, 1945 by I-58 became known . The Indianapolis was on the way back from Tinian , where it had brought the atomic explosive device for the atomic bomb " Little Boy " intended for later dropping over the Japanese city of Hiroshima .

At the time the USA entered the war, the submarines of the US Navy stationed in the Pacific were assigned to the Asian fleet, which was stationed in Cavite , and to the Pacific fleet, which was based in Pearl Harbor . In December 1941, a total of 114 US submarines were in service and 79 more were under construction. Most of these were stationed in the Pacific. Together with the boats of the Dutch Navy stationed in Indonesia , the Allies had just as many submarines in the Pacific as the Imperial Japanese Navy .

In addition to fighting the ships of the Japanese war and merchant navy, the submarines of the US Navy fulfilled transport tasks, for example for underground fighters or special forces, reconnaissance or were used to rescue their own aircraft crews from distress at sea. They operated in groups of two or three boats called " Wolfpack ", which, unlike the German wolf packs, stayed together during the entire patrol. The US Navy submarines achieved great successes both against Japanese warships, such as the sinking of the Shinano , and against Japanese merchant shipping. The success in the fight against merchant shipping was also helped by the view of the Japanese naval leadership that fighting other warships is "more honorable" for warships than protecting merchant ships. Therefore, there was hardly any organized convoy security comparable to the efforts of the Allies .

The bottlenecks in Japanese military supplies and raw material supplies for the motherland due to losses in merchant shipping contributed significantly to the Allied victory in the Pacific. 2% of the American naval personnel were ultimately responsible for 55% of the total destroyed tonnage of Japanese merchant shipping. The US Navy lost 52 submarines, killing over 3500 crew members - at 22%, this is the highest rate of casualties of any branch of the US armed forces in World War II. Nevertheless, in contrast to the defeats of the German navy in both world wars, the war in the Pacific is the only example of a successfully waged submarine war.

After the Second World War

In the Nuremberg war crimes trials, submarine warfare was newly regulated under international law through recognition of German naval warfare. As a result, the Soviet Union built up a very large submarine fleet that could threaten NATO's sea connections . In contrast, NATO developed its strategies for fighting submarines ( SOSUS , hunting submarines , aerial surveillance).

The operational doctrine of both power blocs envisaged threatening the enemy space by stationing missile submarines, eliminating them in turn with hunting submarines and, moreover, returning to combat enemy warships, infiltrating enemy waters for the purpose of espionage, or smuggling combat swimmers . Smaller, conventionally powered submarines should perform comparable tasks in the defense of their own waters by repelling invasion forces.

Conflict India - Pakistan

The first fighting with submarines after the Second World War was strategically and tactically more in the tradition of the fighting of the two world wars. Submarines were not used in combat until 1971 in the Bangladesh war . With India's brief intervention in the fighting over Bangladesh in December of that year, rivalries between India and its neighboring country Pakistan began at sea . In the course of the fighting, the Pakistani submarine PNS Hangor , a boat of the French Daphné class , sank the Indian frigate INS Khukri on December 9, 1971 . In return, the PNS Ghazi had already been lost under unexplained circumstances , whereupon the Indian Navy claimed the sinking of the submarine, but Pakistan spoke of an accident while laying a mine.

Falklands War

In the Falklands War , however, the paradigm shift described above became apparent : the British submarine HMS Conqueror was the first British unit in the Falkland Islands and gained information for the first landings by troops of the SAS and SBS . Later it was used to secure the fleet and sank the Argentine cruiser General Belgrano on May 2, 1982 . Argentina also used submarines in the Falklands War, but without success. Of the four boats in the fleet, two, the Santiago del Estero (ex- Chivo ) and the Salta , were out of action with engine damage. The third boat, the former Catfish now known as Santa Fe , was hit with anti-tank weapons from helicopters on April 25 and damaged so badly that it was thrown onto the beach in South Georgia . The San Luis, on the other hand, a class 209 boat built in Germany , was in service throughout the war without being discovered by British units. However, the attacks she led against British frigates and destroyers took place at too great a distance, so that all torpedoes fired had used up their battery supply before reaching the targets.

Processing

The submarine war, especially that of World War II, has become a central theme in numerous books, films and, more recently, computer games.

First World War

As early as the First World War, Edgar von Spiegel von und zu Peckelsheim processed his experiences from the submarine war in literary terms . In 1930 he translated Lowell Thomas' non-fiction book Raiders of the Deep as Knight of the Deep (first edition Bertelsmann , Gütersloh ) into German, which had eight editions between 1930 and 1942.

In the US film Q-Ships from 1928, the system of the submarine trap was staged for the first time. Numerous feature films and documentaries use the source material of the 1917 documentary The Magic Belt , which was shown again from 1921 under the title Auf Feindfahrt mit U 35 . In 1920 a French and an English version appeared.

The topic of the submarine trap in Q-Ships was taken up in the German film Morgenrot from 1933. Up to this point it was one of the most lavishly produced submarine films of all.

Second World War

literature

As a member of the propaganda company , the so-called "PK-Mann", Wolfgang Frank Dönitz's staff was assigned and had already published propaganda publications during the war. The doctor of law wrote articles for the propaganda magazine "Die Kriegsmarine", which served to attract young talent, but was also represented with articles in the official organ of the Kriegsmarine, the Nauticus . His literary treatment of the overall theme, The Wolves and the Admiral. Triumph und Tragik der U-Boats was published in 1953, was translated into English and French over the next few years and became an international bestseller, which to this day has several thousand editions by various publishers and with subtitles adapted to the zeitgeist - most recently in 2011 in Weltbild as Die Wölfe und der Admiral: U-Boats in action - appeared. With the novel Sharks and Small Fish , published three years later , the author Wolfgang Ott presented the most complete literary adaptation of the naval war to date, in which not only, as previously and subsequently, the fate and work of the officers' ranks was examined. In his work, which has been translated into seven languages, Wolfgang Ott describes the life of a young naval officer as lost and betrayed by the perverted politics of National Socialism. Hans Herlin chose a journalistic approach in his 1959 work Verdammter Atlantik . In five short reports, Herlin traces episodes in which the submarine commanders Prien , Lüth , Henke , Eck and Zschech , who are to be regarded as atypical , get entangled in their fate, the “damned Atlantic”, in the manner of the classic tragedy, and finally go under - just one of them, literally. The equation of submarine drivers with the suffering heroes of the Greek tragedy was taken up again by the author Lothar-Günther Buchheim in his book Das Boot in the early 1970s . Like Frank, Buchheim was deployed in the war as a PK man with the submarine weapon and had produced propaganda material, but drew different conclusions than this one. Like Ott, he also wrote a novel, but, according to the introductory text, saw it “not as fiction”. Buchheim's Das Boot was published in 1973 by Piper-Verlag and goes almost beyond the possibilities of literary form in that it can be read not only as a fateful tragedy, but as a non-fiction book about the submarine war from the perspective of the crews. Buchheim's novel sparked controversy and prompted protagonists of the submarine war, such as Eberhard Godt , on behalf of the former commanders and Adalbert Schnee , in his function as President of the Association of German U-Boat Drivers , to distance themselves and to make devastating judgments. To this day, Das Boot is considered the best novel of the genre.

Movies

One of the first feature films to deal with the submarine war in World War II was the US production Mystery Sea Raider from 1940. The German propaganda film U-Boats westward! produced by Günther Rittau , in which Karl Dönitz appeared by assembling documentary film material. One of the most popular submarine films of the 1950s was Duel in the Atlantic (1957) with Robert Mitchum as the destroyer captain and Curd Jürgens as the submarine commander. In contrast, life on board a submarine and its maintenance problems towards the end of World War II are portrayed in a very humorous way in the 1959 military clothing company Petticoat , with Cary Grant as its commander and Tony Curtis as its procurement officer. The 1957 cinematic processing of Ott's novel based on his screenplay under the title Sharks and Small Fish deals with the topic of war a lot more realistically. In the following year, U 47 - Kapitänleutnant Prien appeared, a very free interpretation of the posture, actions and fate of the eponymous Günther Prien , who is reinterpreted as an internal resister. In contrast, the film adaptation of Buchheim's novel is considered very realistic. After four years of shooting with the help of the author, the film was released in 1981 under the title Das Boot . The film is considered a turning point in the artistic treatment of the submarine war. Buchheim, however, was dissatisfied with the work of director Wolfgang Petersen in several ways. In his illustrated book documenting the shooting, which appeared at the same time as the movie, he criticized the fact that the film was too action-heavy, that it would have been made better than a black-and-white film in the manner of a television play and that the setting, equipment and behavior of the actors were historically incorrect . The six-part television series that was shot at the same time was based on Buchheim's own script, which was originally rejected by Bavaria .

Cold War

Modern nuclear submarines of the Cold War , on the other hand, are thematized by u. a. the thriller Hunt for Red October from 1990, Crimson Tide from 1995 or K-19 - Showdown in the Depth from 2002.

Computer games

Silent Service and Aces of the Deep were early computer game implementations by submarines from World War II . The games in the Silent Hunter series are also well-known , the most recent of which was released in March 2010. The submarine simulator Das Boot placed particular emphasis on realism; different torpedoes and rudimentary radar devices could be used. The game Wolfpack offered the opportunity to control surface vehicles in addition to submarines and thus enabled an interesting insight into the ASW warfare, also from the perspective of the security vehicles in the era of the Second World War.

A submarine simulation is also available as open source software under the name Danger from the Deep . Computer game implementations of modern submarines were the game Red Storm Rising from 1989 by the company MicroProse and the series of submarine simulations by the manufacturer Electronic Arts, which began with 688 Attack Sub . This series took place in modern times with 688 (i) Hunter Killer , Sub Command (2001) and Dangerous Waters (2005) by the manufacturer Sonalysts Inc. continued.

See also

literature

- Clay Blair : Silent Victory. The US Submarine War Against Japan. Lippincott, Philadelphia PA et al. 1975, ISBN 0-397-00753-1 .

- Clay Blair: The Submarine War. 2 volumes. Bechtermünz, Augsburg 2001;

- Volume 1: The Hunters 1939–1942. ISBN 3-8289-0512-9 ;

- Volume 2: The Hunted 1942–1945. ISBN 3-8289-0512-9 .

- Jochen Brennecke : hunters - hunted. German submarines. 1939–1945 (= Heyne books. 1, Heyne general series. No. 6753). Approved, unabridged paperback edition, 4th edition. Heyne, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-453-02356-0 .

- John Costello, Terry Hughes: Atlantic battle (= Bastei-Lübbe-Taschenbuch. Vol. 65038). 4th edition. Bastei Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1992, ISBN 3-404-65038-7 .

- Marc Debus, Alfred Nell: The last escort. From the outpost boat to the submarine fleet. Verlags-Haus Monsenstein and Vannerdat, Münster 2008, ISBN 978-3-86582-677-0 .

- Michael L. Hadley: The Myth of the German Submarine Gun. Mittler & Sohn Verlag, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-8132-0771-4 .

- Lars Hellwinkel: Hitler's Gate to the Atlantic. The German naval bases in France 1940–1945. Ch.links, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86153-672-7 .

- Gaylord TM Kelshall: Submarine War in the Caribbean 1942–1945. Translated and revised by Hans-Jürgen Steffen. Mittler & Sohn, Hamburg et al. 1999, ISBN 3-8132-0547-9 .

- Franz Kurowski : war under water. Submarines on the Seven Seas 1939–1945. Econ-Verlag, Düsseldorf et al. 1979, ISBN 3-430-15832-X .

- David Miller: German U-Boats up to 1945. A comprehensive overview. Motorbuch-Verlag et al., Stuttgart et al. 2000, ISBN 3-7276-7134-3 .

- Frank Nägler : Concepts of submarine warfare before the First World War. In: Stephan Huck (Ed.): 100 years of submarines in German navies. Events - technology - mentalities - reception (= small series of publications on military and naval history. Vol. 18). With the collaboration of Cord Eberspächer, Hajo Neumann and Gerhard Wiechmann. With contributions by Torsten Diedrich , Peter Hauschildt, Linda Maria Koldau , Klaus Mattes, Karl Nägler, Hajo Neumann, Kathrin Orth, Michael Ozegowski, Werner Rahn , René Schilling, Heinrich Walle and Raimund Wallner. Dr. Dieter Winkler, Bochum 2011, ISBN 978-3-89911-115-6 , pp. 15-26.

- Léonce Peillard : History of the Submarine War. 1939-1945 (= Heyne-Bücher. 5060, ZDB -ID 2080203-1 ). 17th edition. Heyne, Munich 1997.

- Werner Rahn: German submarines in the First and Second World War: missions, experiences and development of new submarine types. In: Stephan Huck (Ed.): 100 years of submarines in German navies. Events - technology - mentalities - reception (= small series of publications on military and naval history. Vol. 18). With the collaboration of Cord Eberspächer, Hajo Neumann and Gerhard Wiechmann. With contributions by Torsten Diedrich, Peter Hauschildt, Linda Maria Koldau, Klaus Mattes, Karl Nägler, Hajo Neumann, Kathrin Orth, Michael Ozegowski, Werner Rahn, René Schilling, Heinrich Walle and Raimund Wallner. Dr. Dieter Winkler, Bochum 2011, ISBN 978-3-89911-115-6 , pp. 27-68.

- Joachim Schröder: The emperor's submarines. The history of the German submarine war against Great Britain in World War I (= Subsidia Academica. Series A: Newer and Recent History. Vol. 3). Bernard and Graefe, Bonn 2003, ISBN 3-7637-6235-3 (also: Dortmund, Universität, Dissertation, 1999).

- VE Tarrant: West course. The German submarine offensives 1914–1945. 3. Edition. Motorbuch-Verlag, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-613-01542-0 .

- Tomas Termote: Underwater War. Submarine Flotilla Flanders 1915-1918 , Hamburg (Mittler) 2015. ISBN 978-3-8132-0959-4 .

- Daniel Uziel: "Gray Wolves - Knights of the Deep". Nazi propaganda as the leitmotif of today's depiction of the submarine war , in: Jens Westemeier (ed.): "That was how the German soldier ...". The popular picture of the Wehrmacht , pp. 227-245, Paderborn (Ferdinand Schöningh) 2019. ISBN 3-506-78770-5 .

- Dan van der Vat: Battlefield Atlantic. The German-British naval war. 1939–1945 (= Heyne books. 8112). Heyne, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-453-04230-1 .

Web links

- The unrestricted submarine war 1914–1918 at the DHM

- The Submarine War 1914–1918

- Submarine War 1914–1918 Ships sunk and damaged by submarines 1914–1918 (English)

- Submarine War 1939–1945 Ships sunk and damaged by submarines 1939–1945 (English)

- German submarines, u. a. with crew lists and war diaries (German and English)

- Duikboot: Operations and fate of German submarines 1936 to 1945 database (Dutch, partly German, English)

- Submarine successes of the Axis powers 1939–1945 Database (German, English)

- Allied submarine attacks 1939–1945 in Europe database

- Antisubmarine Warfare in World War II Detailed report on the use and defense of German submarines in World War II

- Historical footage of submarines from the First World War , European Film Gateway (EFG)

Remarks

- ↑ A view that is no longer unreservedly shared today. Cf. for example Clay Blair Der U-Boot-Krieg 1939–1945 , 2 vols., Augsburg 1998, p. 615: “Nevertheless, the myth of the heroism of the submarine drivers and the invincibility of their boats appeared for the second time in this one Century established in public opinion. […] For this reason [actual sinking numbers] […] it remains a mystery to this day why Churchill assured after the war that only the submarine danger really worried him during the war. "

Individual evidence

-

↑ The information in the sources is different:

114-128: Walter A. Hazen: Everyday Life: World War I: with Cross-curricular Activities in Each Chapter . Good Year Books, 2006, ISBN 1-59647-074-7 , p. 52.

123: Sally Dumaux: King Baggot: A Biography and Filmography of the First King of the Movies . McFarland, 2002, ISBN 0-7864-1350-6 , p. 100.

128: Charles Harrell, Rhonda S. Harrell: History's Moments Revealed: American Historical Tableaus Teacher's Edition . iUniverse, 2006, ISBN 0-595-40026-4 , p. 152. - ↑ Andreas Michelsen: The U-Boat War 1914-1918 . by Hase & Koehler Verlag, Leipzig 1925, p. 139.

- ^ Documentary film with Goebbels' original voice about Athenia, minute 7:20 ( memento from November 14, 2013 in the Internet Archive ). In: YouTube .

- ↑ Jürgen Rohwer , Gerhard Hümmelchen : Chronicle of the Naval War 1939 August / September . In: Württemberg State Library . 2007.

- ^ A b Clay Blair: Der U-Boot-Krieg, Die Jäger 1939–1942 , Wilhelm Heyne Verlag, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-453-12345-X , pp. 849–850.

- ↑ Karl Alman: Gray Wolves in a Blue Sea - The Use of German U-Boats in the Mediterranean . Heyne Verlag , Munich 1995, ISBN 3-453-01193-7 , p. 301 .

- ^ Hans Michael Kloth: U-Boats on the Autobahn . In: one day . February 4, 2008, accessed November 21, 2016.

- ^ Gerd Enders: German U-Boats in the Black Sea: 1942–1944 . ES Mittler & Sohn , Hamburg, Berlin, Bonn 1997, ISBN 978-3-8132-0761-3 , pp. 136 .

- ↑ Shadows aft . In: Der Spiegel . No. 20 , 1965 ( online ).

- ↑ a b Jürgen Gebauer, Egon Krenz: Marine Encyclopedia . Brandenburg. V., Bln, 1999, ISBN 3-89488-078-3 , p. 463 .

- ↑ After handing over their boat to the Japanese, they drove with the blockade breaker Osorno to Singapore , where they arrived on October 10, 1943, and then on to Penang. ( http://www.u-boot-archiv.de/dieboote/u0511.php )

- ↑ Eberhard Rössler : History of the German submarine building . Bernard & Graefe, Augsburg 1996, Volume 2, p. 314. ISBN 978-3-76375-800-5 .

- ↑ Lothar-Günther Buchheim : The truth stayed on the diving station . In: Geo . No. 10 , 1981, ISSN 0342-8311 ( uni-marburg.de ).

- ^ Antony Preston: Flotten des 2. Weltkrieges , Verlag Gerhard Stalling, Oldenburg and Hamburg 1976, (English: "An illustrated History of the Navies of World War II", Hamlyn Publishing Group ltd.), P. 133.

- ^ Antony Preston: Flotten des 2. Weltkrieges , Verlag Gerhard Stalling, Oldenburg and Hamburg 1976, (English: "An illustrated History of the Navies of World War II", Hamlyn Publishing Group ltd.), P. 202.

- ^ A b Working Group for Defense Research (ed.): Elmar B. Potter, Chester W. Nimitz : Seemacht Seekriegsgeschichte From Antiquity to the Present , translated by Jürgen Rohwer , Manfred Pawlak Verlag, Herrsching 1982, ISBN 3-88199-082-8 , P. 866.

- ↑ Jürgen Schlemm: The U-Boat War 1939-1945 in the literature An annotated bibliography . Elbe-Spree-Verlag 2000, p. 170. (entry)

- ↑ Michael Hadley: The myth of the German submarine weapon . 2001, p. 104.

- ^ Jürgen Schlemm: The submarine war 1939-1945 in literature. An annotated bibliography. Elbe-Spree-Verlag 2000, p. 94.

- ↑ Michael Hadley: Der Mythos der Deutschen U-Bootwaffe , 2001, p. 157.

- ↑ Michael Hadley: Der Mythos der Deutschen U-Bootwaffe , 2001, p. 109.

- ↑ Dieter Hartwig: Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz Legend and Reality . 2010, p. 267.

- ↑ Michael Salewski: On the Reality of War . 1976, p. 53 f. ISBN 978-3-42301-213-3 .

- ↑ Michael Hadley: The myth of the German submarine weapon . 2001, p. 124. ISBN 978-3-81320-771-2 .

- ↑ Michael Hadley: Der Mythos der Deutschen U-Bootwaffe , 2001, p. 129.

- ^ Lothar-Günther Buchheim: The film: The boat . Goldmann, Munich, 1981, ISBN 3-442-10-196-4 .

- ↑ Michael Hadley: Der Mythos der Deutschen U-Bootwaffe , 2001, p. 132.