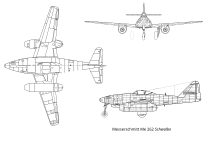

Messerschmitt Me 262

| Messerschmitt Me 262 | |

|---|---|

Replica of a Messerschmitt Me 262 in flight at the ILA 2006 |

|

| Type: | Jet-powered fighter-bomber |

| Design country: | |

| Manufacturer: | |

| First flight: |

July 18, 1942 |

| Commissioning: |

1944 |

| Production time: |

1943-1945 |

| Number of pieces: |

1433 |

The Messerschmitt Me 262 , a development by Messerschmitt AG , Augsburg , was the first jet aircraft to be built in series . 1433 copies of the twin-engine machine were built between 1943 and 1945, around 800 of which were delivered to the Wehrmacht's air force during the Second World War . Like the Me 163 and the Heinkel He 280, the aircraft was developed with medium to low priority from the beginning of 1939. At the same time, Messerschmitt AG distributed its development potential to types such as B. the Me 261 , the Me 210 , the Me 264 and the Me 309 . None of these aircraft reached series production.

history

development

The predecessor company of Messerschmitt AG, Bayerische Flugzeugwerke AG , received an order from the Reich Ministry of Aviation (RLM) in autumn 1938 to develop an air jet-powered fighter aircraft. The project was given the designation P 1065. The project manager was Woldemar Voigt . A wooden dummy was created by November / December 1939, which was positively assessed by employees of the RLM and in March 1940 led to the order for the construction of three prototypes .

prototype

In April 1941 the first test aircraft was completed. Around the same time issued the RLM the new model officially the number 262. Since the P-3302 jet engines of BMW (later BMW 003 called) was not available, was first to a centrally mounted in the bow Junkers Jumo 210 G piston engine resorted . A total of 47 test flights were carried out in this configuration, with problematic oscillations of the rudders at higher speeds. The first flight of the prototype Me 262 V1 in this configuration took place on April 18, 1941. The first flight with two BMW P 3302 test engines was completed on March 25, 1942.

First flight

On July 18, 1942 Messerschmitt chief pilot succeeded Fritz Wendel from the airport Leipheim with the Me 262 V3 the first flight with the planned for production models jet engines of the type Jumo 004 of Junkerswerke , the larger and heavier, but also considerably more powerful than the BMW engines were. Wendel was only able to start the machine , which at that time was still equipped with a tail wheel landing gear , by briefly pressing the brake at a roll speed of around 180 km / h in order to raise the tail of the aircraft and thus achieve a flow of air against the elevator, which was released from the wings when rolling was covered up and had no effect. These launch characteristics prompted the RLM to request a nose wheel landing gear for later series production. The rearward displacement of the main landing gear required for the conversion resulted in extensive changes to the wing structures; only the Me 262 V5 was equipped with such a landing gear. It turned out to be problematic that, due to the not yet fully developed regulation of the engines, when they were shut down into idle mode, excessive smoke was generated in the turbines and smoke and exhaust gases penetrated into the cabin.

Hitler's vision of a lightning bomber

On November 26, 1943, the Me 262 Adolf Hitler , equipped with a nose wheel from the V5 onwards, was presented. Allegedly Hitler asked the company boss Willy Messerschmitt whether the machine could be loaded with bombs, which he answered in the affirmative, as investigations had already been carried out in this regard. Hitler agreed to mass production on the condition that the aircraft should be used primarily as a bomber (so-called "lightning bomber"), which he urgently needed to ward off the expected Allied landing. This decision turned out to be a strategic mistake: The Me 262 was designed as an interceptor and, due to the pilot's limited field of vision on the ground, had a comparatively poor accuracy when dropping bombs.

The controversy over whether the Me 262 should be designed as a fighter-bomber or a fighter continued. All attempts to persuade Hitler to give priority to the hunter version failed. The dispute over the use of the Me 262 culminated in a rift between Hitler and the air force command. Field Marshal Erhard Milch allegedly countered Hitler's order to use the Me 262 as a fighter-bomber :

"My Führer, every child can see that this is not a bomber, but a fighter!"

Carrying external loads (usually two bombs weighing 250 kg each) meant that the Messerschmitt fell back into the speed range of the Allied fighters. The main reason for the delays until the Me 262 was ready for operation was the immense difficulties with the jet engines .

The Japanese military attaché in Germany witnessed several test flights of the Me 262 and sent reports about them to Japan in September 1944 . There it was decided to develop jet fighters as well - the Nakajima J9Y Kikka and the Nakajima Ki-201 .

Front use

The first missions at the front on a very small scale took place in the summer of 1944 by Erprobungskommando 262, the establishment of which had already started at the end of December 1943. From the spring of 1944, the Einsatzkommando Schenk tested the bombing of the Me 262 for the first time. The first attack with the Me 262 jet fighter succeeded Lieutenant Alfred Schreiber on July 26, 1944, when he shot at an unarmed Mosquito reconnaissance machine broke away from the plane, believed to have damaged and shot down the plane. The part was the outer exit hatch of the Mosquito, which the pilot then steered in clouds and, due to the damage, flew on to Italy to land. From August 1944, the first fighter-bomber missions over France were flown by the Schenk Command. In the summer of 1944 further combat, hunting, reconnaissance and night hunting units were set up. In the first month of operation, the Nowotny Command reported the shooting down of four enemy heavy bombers, twelve fighters and three reconnaissance aircraft. In 1945 the fighter-bomber units, which operated with moderate success, were increasingly used for hunting missions. The first concentrated attack by 26 Me 262s on an American bomber formation took place on March 3, 1945. On March 18, 1945, 37 Me 262 formations of 1221 bombers and 632 fighters attacked (each Me 262 was armed with 24 R4M air-to-air missiles). Thirteen bombers and six escort fighters were shot down with two losses of their own. 15 bombers were so badly damaged that it was no longer worth repairing. In another mission, 25 machines were shot down from a formation of 425 B-17s without losses of their own. The maximum number of flights of the Me 262 took place on April 10, 1945. Ten bombers were shot down in 55 missions of the Me 262, but this time its own losses amounted to 27 fighters.

One of the most successful pilots of the Me 262 was Kurt Welter .

Me-262 pilots claimed to have shot down a total of 542 Allied aircraft. Jet fighters of all kinds have achieved 745 victories. A Hawker Tempest was the first aircraft to shoot down a Me 262. In addition, the field airfields of the Me 262 were "shaded" in order to shoot down aircraft landing, which is why a unit of the Me 262 needed its own airspace protection around its base with propeller fighter planes.

production

A total of 1433 Me 262s were built, of which mostly no more than 100 machines were operational at the same time. The reasons for this were the massive bombing attacks by the Allies and the lack of fuel and spare parts, as well as the lack of trained pilots. Nevertheless, towards the end of the war, under the leadership of the SS-owned Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke GmbH (DEST), mass production of hulls began on a large scale in the then top-secret underground production complex B8 Bergkristall in St. Georgen an der Gusen . From May 1945 up to 1250 machines were to roll off the assembly line there every month. The wings were produced between April 1944 and April 1945 by prisoners of the Leonberg concentration camp in the tubes of the Engelberg tunnel. From January 1944 the hulls of the Me 262 were manufactured in the Obertraubling plant and assemblies from the summer of 1944 in the “Staufen” forest plant (near Obertraubling ). Other production sites in the final phase of the war were the Walpersberg near Kahla , Leipheim , Burgau and Horgau with a newly built satellite camp of the Dachau concentration camp, the Burgau concentration camp .

The final assembly took place at Messerschmitt in Augsburg (MttA), Leipheim (MttL), in the Obertraubling plant , in a camouflaged plant near the Schwäbisch Hall-Hessental air base and at the lightweight construction in Budweis (LBB). The series started in April 1944, the last aircraft were delivered in April 1945. There is evidence of 1369 aircraft up to April 10, 1945. Since Augsburg was not occupied until April 28, 1945, the above figure of 1433 aircraft can be correct. By November 30, 1944, 212 A-2 lightning bombers and 228 A-1 fighters had been produced. After that only the A-1 was produced. By the end of March 1945, 33 conversions to close-up reconnaissance aircraft and 26 conversions to B-1 training aircraft were made by Blohm & Voss / Hamburger Flugzeugbau (16 pieces) and Deutsche Lufthansa, Staaken (10 pieces). Four night fighters B-1 / U1 were manufactured from the B-1 by the DLH Staaken by April 10, 1945.

| month | MttA | MttL | LBB | div. | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 1944 | 16 | 16 | |||

| May 1944 | 7th | 7th | |||

| June 1944 | 28 | 28 | |||

| July 1944 | 59 | 59 | |||

| August 1944 | 20th | 20th | |||

| September 1944 | 91 | 91 | |||

| October 1944 | 117 | 117 | |||

| November 1944 | 20th | 81 | 101 | ||

| December 1944 | 102 | 23 | 125 | ||

| January 1945 | 43 | 117 | 6th | 166 | |

| February 1945 | 296 | 296 | |||

| March 1945 | 295 | 295 | |||

| until April 10, 1945 | 47 | 47 | |||

| total | 503 | 221 | 6th | 638 | 1368 |

By April 10, 1945, the Luftwaffe had been assigned a total of 1,039 aircraft. Over 200 aircraft were destroyed or damaged after their takeover. The units had suffered 727 losses, 232 of them due to enemy action. There were still 264 aircraft in the fleet, 134 of them at the enemy, i.e. in operational units. Due to the scarcity of light metal, the switch to wood was investigated. Several Me 262s received a tail unit made of wood, which was designed and built by Jacobs-Schweyer (company owner Hans Jacobs ) in Darmstadt. The completion of wooden hulls (from the pilot to the rear) was no longer possible; three wooden test hulls were built.

Aviation historical significance

Along with the Arado Ar 234 , the Heinkel He 162 and the Horten H IX , the Me 262 was the most technically advanced aircraft of its time. After the end of the Second World War, a number of complete Me-262 aircraft as well as components and construction plans fell into the hands of the Americans and the Soviet Union as looted goods . In this way, the Me 262 significantly influenced the further development of jet-powered fighter aircraft after the Second World War. The sweep of the wing, however, was a result of chance; the retraction of the outer wing is said to be due to a shift in the center of gravity either when the fuselage is redesigned or the engines are used; the wing should therefore simply compensate for the offset center of gravity.

Mission profile

The jet engines of the Me 262 delivered at low speed in comparison with propeller contrast -Antrieben relatively little, at high speed, comparatively large amount of thrust (in Me 262 around 5150 kW / 7000 PS); in addition, the machine was less maneuverable than the Allied fighters because of its high mass. Furthermore, the engines tended to partially flame out when the thrust was given quickly ; In addition, there was the disadvantage that turbines show a poorer part-load behavior than conventional piston engines and thus deliver significantly less thrust with only a slight reduction in power. Thus it was tactically unsuitable as an air superiority fighter and entirely geared towards its role as an interceptor. Due to its high speed, however, it had the advantage of tactical initiative, which was particularly useful against the majority of Allied hunters. The general of the fighter pilots, Adolf Galland , said that one Me-262 jet fighter was of greater value than five Messerschmitt Bf 109 propeller fighters . When he flew the Me 262 for the first time, he was so enthusiastic about the flight characteristics and the speed of the machine that after the flight he said: "It's like an angel pushing".

The large Allied bomber formations, which were protected on the one hand by strong defensive armament and on the other by long-range escort fighters, became a challenge that could no longer be overcome for conventional day hunting with propeller fighters approaching from the front. Due to the high speed of the Me 262 (speed difference to the bombers about 400 km / h, to the escort fighters more than 100 km / h) and the very strong armament (only a few well-placed hits by the four MK-108 -30-mm- On-board cannons from Rheinmetall were enough to destroy a heavy bomber), many pilots saw an opportunity to do their job again.

As the Reich Defense had increasing difficulties in training enough pilots for aerial battles against bombers and their escort fighters, the RLM developed the plan to fight the bomber fleets on their own bases. Colonel Steinhoff tried to change Hitler's mind on the occasion of the awarding of the swords to the Knight's Cross. The latter did not want to hear about it and issued an order from the Fiihrer: "With immediate effect, I hereby forbid talking about the Me 262 jet aircraft, except about the fastest or lightning bomber". So he allowed the construction exclusively as a high-speed bomber. However, this did not lead to any practical use, since the 262 was planned as a fighter: The acceptance of a bomb load of 1000 kg in front of the front center of gravity required the waiver of two of the four automatic cannons in the nose of the fuselage and the refueling of the front fuel tanks. In addition, the pilot first had to “fly off” fuel for at least 40 minutes in order to produce a trim position suitable for throwing. Nevertheless, the bombing remained critical: Immediately after the bomb locks were triggered, the machine became so tail-heavy that a sudden pitching moment around the transverse axis set in, which not infrequently led to structural damage to the wings in the area of the engine nacelles. Furthermore, due to the high speed of the launch, combined with the lack of aiming equipment, the probability of being hit was low; Messerschmitt's test pilot Fritz Wendel, who accompanied the jet fighters on these troop tests, noted this very clearly in his reports. Because of these problems, the maximum bomb load of 2 × 500 kg was not usually carried when bombing, but the far less problematic equipment of 2 × 250 kg, so that the machine was less tail-heavy. The amateurish “Führer's order” was all the more incomprehensible because the Arado Ar 234 was already a powerful tactical bomber that was able to perform these tasks much better. However, recent research shows that Willy Messerschmitt himself was the cause of this decision, which was apostrophized as the “tragedy of German air armament”, because he introduced Hitler to this idea in June and September 1943 for reasons of power politics.

During high-speed test flights, Messerschmitt found that the Me 262 became increasingly top- heavy at speeds above Mach 0.83 and Mach 0.86 was the upper limit for a dive in which interception was still possible. It is therefore extremely unlikely, as Hans Guido Mutke claims, that the Me 262 has actually ever reached supersonic speed . However, in many parts of the aircraft (for example the wings) the air is deflected and accelerated to such an extent that in some areas the air moves at supersonic speed relative to the aircraft. This can create a compression wave that gives the impression that the Me 262 is flying at Mach 1. However, their mach numbers were still higher than those of any allied hunter.

Since there was no air brake and neither propellers nor poor aerodynamics slowed the aircraft, the Me 262 could only be used poorly in a dive. In addition, due to the lack of braking, she had a long landing approach during which she was easy prey. Jet engines respond more slowly than piston engines. The Jumos tended to suffer a burst of flame when accelerating too abruptly , with the engine stalling and having to be restarted, which was problematic shortly before landing. The Mustangs , Tempests and Thunderbolts lurked at low altitudes near the Me-262 airfields to pounce on the then sluggish aircraft. Because of this, other hunting units with Fw-190 or Bf-109 piston fighters had to be parked specifically to protect these airfields. In addition, up to 500 anti-aircraft tubes were used around the airfields.

Noteworthy in connection with production streamlining, fuel and staff shortages is the fact that there were two-seater variants of the Me 262, but the sample training (familiarization with the new aircraft) rarely took place in the two-seater, but rather by "watching and imitating". The control room - even without flight experience - explained the systems and their handling to the pilots, and the pilots asked their comrades about approach heights and power settings. Against the background of completely new technology and the challenge that a jet aircraft poses to its pilot, this is a clear indication of the desperate situation of the air forces, shortly before the defeat and now without functional structures to maintain the fight.

Associations

- Trial Command 262 (Ekdo.-262) III./ZG 26

- Task Force Schenk (E-51) 3./KG 51 "Edelweiss"

-

Combat Squadron (Jagd) 51 - KG (J) 51

- I./KG(J) 51

- II./KG(J) 51

- IV./(Erg.) 51

- Command Nowotny III./JG 6

- Supplementary Fighter Squadron 2 - EJG 2

-

Combat Squadron (Jagd) 54 - KG (J) 54

- I./KG(J)54

- II./KG(J)54

- III./KG(J)54

- Command Welter 10./NJG 11

- Close reconnaissance group 6 - NAGr 6

-

Jagdgeschwader 7 - JG 7

- I./JG 7

- II./JG 7

- III./JG 7

- Jagdverband 44 - JV 44 (Galland's "Experts")

Versions and armament

Me 262 A-1a "Schwalbe" - interceptor

- Jumo 004 engines

- four automatic cannons MK 108 , caliber 30 mm, rigid in the fuselage bow

- the two top automatic cannons with 100 rounds each,

- the two lower automatic cannons with 80 rounds each.

Me 262 A-1b

- like A-1a, but with BMW-003 engines - only a few prototypes

Me 262 A-2 "Sturmvogel" - fighter-bomber

- two MK 108 with 100 rounds each

- Suspension devices for max. 1000 kg bombs

Me 262 A-5 or A-1a / U3 - reconnaissance aircraft

- like A-1a, but with photo equipment in the lower bow

Me 262 B-1a - two-seat school machine

- Armament like A-1a, but reduced internal fuel capacity, drop tanks to compensate

Me 262 B-1a / U1 - conversion of the school machines into night fighters

- like B-1a, but additionally:

Me 262 B-2 - final version of the night fighter

- like B-1a / U1, but slightly longer fuselage for greater internal fuel capacity, only a few prototypes

Me 262 C "Heimatschützer" - prototypes of fast rising interceptors

- Armament like A-1a

- the C-1a with Jumo 004B-2 and a Walter R.II-211/3 (HWK 509) rocket engine, test flights from February 1945

- the C-2b with BMW 003R (combination of a BMW 003A with one BMW 718 rocket engine each), test flights from March 1945

- the C-3 with an additional launchable rocket engine was no longer implemented

Me 262 Lorin - projected fast fighter

- in addition to the Jumo-004 engines, two light Lorin engines (which should only be switched on from a certain speed)

Me 262 HG I - (of high speed) projected fast fighter

- improved aerodynamics (revised tail unit and lower air resistance)

Me 262 HG II - (of high speed) projected fast fighter

- further improved aerodynamics (new wings, stronger sweep)

Me 262 HG III - (of high speed) projected fast fighter

- further improved aerodynamics (sweep 49 degrees)

- Engines in a streamlined transition between wings and fuselage

Experimental weapon installation

- two 30 mm cannons MK 108 and MK 103 and two 20 mm MG 151/20 in the bow (A-1a / U1)

- a machine gun BK5, 50 mm, a test copy (V083, serial number 130083)

- a machine cannon MK 214 , 50 mm, (Me 262 A-1a / U4 "bulk destroyer"). Two test copies (work nos. 111899 and 170083). Work no. 170083 was captured by the Americans at the end of the war and crashed during the transfer flight from Melun to Cherbourg on July 11, 1945.

Regularly used additional armament

- 24 × R4M rockets caliber 55 mm

In addition, there were plans towards the end of the war, among other things, for equipment with six cannons and the “Wabe” device (see Ba 349 “Natter” ) as additional armament. A number of different designs were created, but they were no longer realized:

- Me P.1099 A: Version with significantly enlarged hull

- Me P.1099B: heavily armed destroyer

- Me P.1100 / I: heavy fighter with engines on the wing approach

- Me P.1100 / II: Variant of the P.1100 with the wings of the Me 262 HGIII

The Me 262 A-1a was equipped with two self-sealing fuel tanks , each with a capacity of around 900 liters; there was also a rear tank with 600 liters and optionally a tank with 170 liters in the cockpit (possibly 200 liters). A tank consisted of three layers. The inner layer formed a coated fabric, the middle layer consisted of swellable natural rubber, the outer layer was made of swell-resistant synthetic rubber (Perbunan). When a bullet hit, the fuel spilled out caused the middle layer to swell and thus closed the leaks. One tank was installed in front of and two tanks behind the cockpit. The shape of the tanks was adapted to the triangular cross-section of the hull.

The scales and pointers of the instruments were provided with radioactive luminous paint so that they could be read without lighting during night use. For this reason, yellow adhesive tape with the black inscription “RADIOACTIVE” is affixed to the cockpit of the Me 262 (work number 500071) on display in the Deutsches Museum .

Testing by the Allies

The British tested the Me-262 in Farnborough and flew at a speed of Mach 0.84 in a stinging flight, which confirmed Messerschmitt's statements.

Operation Seahorse

Airworthy copies of the Me 262, Arado Ar 234, Heinkel He 219 and Horten IX were also transferred to the port of Cherbourg under the direction of Colonel Harold E. Watson. Lieutenant Colonel “Bud” Seashaw was in charge of loading the machines onto the British aircraft carrier HMS Reaper , so that the operation, derived from this, was quickly named “Seahorse”. The 40 or so planes were brought to Newark , New Jersey, and from there to Newark Army Airfield . The Me 262 intended for testing by the US Navy flew to NAS Patuxent River , those for the USAAF went to Wright Field and the attached Freeman Field in Indiana, where the Foreign Aircraft Evaluation Center was located. During a stopover for refueling at Pittsburgh Airport , hive number 666 burned after a brake failure.

After the flight tests were completed, the remaining specimens were handed over to the 803rd Special Depot, Orchard Place Airport , Park Ridge , Illinois. This inventory of foreign warplanes was later distributed to various aviation museums in the United States.

Czechoslovak post-war version

After the Second World War, ten Me 262s were assembled by the manufacturer Avia in Czechoslovakia from parts that were still there. The seven single-seaters were designated as S-92 and the three two-seat training aircraft as CS-92 in service with the Czechoslovak Air Force . The first machine flew on August 27, 1946. The model remained in service until the early 1950s and was then replaced by Jak-17 / Jak-23 and the license-built MiG-15 . The availability of the MiG-15 made plans by the Yugoslav Air Force redundant to procure S / CS-92 machines. In addition, the non-aligned Yugoslavia was later able to acquire US F-84 and F-86 .

Technical specifications

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| crew | 1 |

| length | 10.60 m |

| span | 12.65 m |

| Wing area | 21.70 m² |

| Wing extension | 7.4 |

| height | 3.84 m |

| Landing speed | 175 km / h |

| Top speed | 870 km / h at an altitude of 6000 m |

| Taxiway | 1300 m |

| Flight time at 9000 m | 13.2 min |

| Range | 1050 km |

| Service ceiling | 11,450 m |

| Total flight time | 50-90 min |

Preserved copies

Some Me 262s have been preserved and exhibited in museums, including:

- Me 262 A-1a in the Deutsches Museum in Munich , ( Germany ). This machine landed on April 25, 1945 in Dübendorf (Switzerland); The only remaining machine on the European mainland in the 1950s, it was handed over to the Deutsches Museum in 1957.

- Me 262 A-1a at the National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in Washington, DC , ( United States )

- Me 262 A-2a in the Royal Air Force Museum in London , ( United Kingdom )

- National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton , ( United States )

- Me 262 B-1a / U1 in the South African National Museum of Military History in Johannesburg , ( South Africa )

- Australian War Memorial in Canberra , ACT , ( Australia )

- Technical Museum in Sinsheim (replica)

- Avia S-92 (Me 262-A) and Avia CS-92 (Me 262 B-1a) in the Aviation Museum Kbely, Prague Post-war buildings as S-92 and CS-92

- National Museum of Naval Aviation, Pensacola ( United States )

New builds: Some replicas were completed in 2004/2005 in Everett, Washington State. One of these machines, which can be flown both as a single-seat and as a two-seat variant with little conversion effort, belongs to the Messerschmitt Foundation in Manching. It flew for the first time on April 25, 2006 with the registration D-IMTT. This machine was then flown for the first time in front of an audience at the International Aviation Exhibition in Berlin-Schönefeld from May 16 to 21, 2006.

In contrast to the original Me 262, the replicas are not powered by the original Jumo engine , but by more modern General Electric J85 / CJ-610 , which are used in jets such as the Gates Learjet , the Northrop F-5 Freedom Fighter or the Cessna A-37 Dragonfly can be used. This drive is readily available and also much safer to operate.

See also

literature

- Manfred Boehme: Jagdgeschwader 7 - The chronicle of a Me 262 squadron. 1944/45. Motorbuch-Verlag, Stuttgart 1977.

- Mano Ziegler : Turbinenjäger Me 262. The story of the world's first operational jet fighter. Motorbuch-Verlag, Stuttgart 1977, ISBN 3-87943-542-1 .

- Manfred Griehl: Me 262 - the multi-purpose aircraft. Podzun-Pallas Verlag, Friedberg 1984.

- Heinrich Hecht: The world's first turbine hunter - Messerschmitt Me 262. Podzun-Pallas Verlag, Friedberg 1979.

- Manfred Jurleit: Jet Fighter Me 262 - The History of Technology. Motorbuch-Verlag, Stuttgart 1995.

- Manfred Jurleit: Me 262 jet fighter - in action. Motorbuch-Verlag, Stuttgart 1995.

- Hugh Morgan: Me 262 Petrel / Swallow. Motorbuch-Verlag, Stuttgart 1996.

- Eric Melrose Brown : Famous Air Force Aircraft 1939–1945. Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-87943-846-3 . (Test report including the Me 262)

- Willy Radinger, Walter Schick: Me 262. Aviatic Verlag, [1] , ISBN 3-925505-21-0 .

- Lutz Budraß : Aircraft Industry and Air Armament in Germany 1918–1945. Düsseldorf 1997.

- J. Richard Smith, Eddie J. Creek: Me 262. Concepts and Development. HEEL-Verlag, Königswinter 1999, ISBN 3-89365-784-3 .

- J. Richard Smith, Eddie J. Creek: Me 262. Testing and Use. HEEL-Verlag, Königswinter 2001, ISBN 3-89880-016-4 .

- Alexander Kartschall: Messerschmitt Me 262 - Secret production facilities. , Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart 2020, ISBN 978-3-613-04258-2 .

Web links

- Luftarchiv.de: Me 262

- A secret matter of command: Me 262 performance improvement, historical source document, February 1945

- Christian Gödecke: Hitler's secret aircraft factories - jet fighters in the thicket. On one day - Spiegel-online from November 30th 2010 (with 14 partly historical photos from 1945),

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Aviation classics. December 14, 2018, accessed October 17, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Under the RADAR: Mosquito versus Me 262 , documentation of the RAF Museum

- ↑ Bernd Wagner [email protected]: The Messerschmitt Me 262. June 1, 2019, accessed on October 17, 2019 .

- ^ Dennis R. Jenkins: Me 262 Sturmvogel. Bechtermünz Verlag, ISBN 3-8289-5339-5 .

- ^ William Green: Warplanes of the Third Reich. Galahad Books, New York 1970, ISBN 978-0-88365-666-2 .

- ^ Hugh Morgan, John Weal: German Jet Aces of World War 2. (Osprey Aircraft of the Aces No 17), Osprey Publishing, London 1998, ISBN 978-1-85532-634-7 .

- ^ Rudolf A. Haunschmied , Jan-Ruth Mills, Siegi Witzany-Durda: St. Georgen-Gusen-Mauthausen - Concentration Camp Mauthausen Reconsidered. BoD, Norderstedt 2008, ISBN 978-3-8334-7440-8 .

- ^ Schmoll: The Messerschmitt works. 2004, pp. 135, 172.

- ↑ Compare C. Gödecke: Jet fighter in the thicket. November 2010.

- ^ BA / MA Freiburg, inventory RL 2III / 624 and RL 3, production planning.

- ^ BA / MA Freiburg, inventory RL 3, production programs.

- ↑ Jurleit: History of technology. Page 199 shows a slightly different table based on information from Messerschmitt employees during a survey by the USAAF in June 1945.

- ^ BA / MA Freiburg, inventory RL 2III / 624.

- ↑ Harold A. Skaarup: Rcaf War Prize Flights, German and Japanese Warbird Survivors , Verlag iUniverse, 2006, ISBN 978-0-595-84005-2 , p. 155

- ↑ (see Walter Schuck: Shooting. )

- ↑ Me P.1099A on Luft46.com .

- ↑ Me P.1099B on Luft46.com .

- ↑ Me P.1100 / I on Luft46.com

- ↑ Me P.1100 / II on Luft46.com

- ↑ Harold A. Skaarup: Rcaf War Prize Flights, German and Japanese Warbird Survivors , Verlag iUniverse, 2006, ISBN 978-0-595-84005-2 , p. 156

- ↑ Hugh Morgan, Isolde Baur: Watson's Whizzers. Part 1. In: Airplane Monthly. December 1994, p. 6.

- ↑ Hugh Morgan, Isolde Baur: Watson's Whizzers. Part 2. In Airplane Monthly. January 1995, p. 9.

- ^ Operation Seahorse: The Voyage Home. Retrieved October 17, 2019 .

- ^ Alfred Price: Messerschmitt Me 262. In: International Air Power Review. Vol. 23, 2007, p. 152.

- ↑ Deutsches Museum: Messerschmitt Me 262 A-1a .

- ↑ National Air and Space Museum: Messerschmitt Me 262A .

- ↑ Royal Air Force Museum: Messerschmitt Me 262A-2a ( Memento from September 5, 2008 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ National Museum of the United States Air Force: Messerschmitt Me 262 A ( memento of October 9, 2014 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ National Museum of Naval Aviation