Atlantic battle

| date | September 3, 1939 - May 7, 1945 |

|---|---|

| place | Atlantic , North Sea , Irish Sea , Labrador Sea , Gulf of Saint Lawrence , Caribbean , Gulf of Mexico , Outer Banks , Arctic Ocean |

| output | Allied victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

|

|

|

| losses | |

|

28,000 sailors |

30,264 seafarers (civil) |

Atlantic battle is a collective term for the fighting between the German navy and warships , convoys and naval aviation forces of the allies in the Atlantic during the entire duration of the Second World War .

After the last heavy German surface forces withdrew from the French Atlantic ports in February 1942 ( Cerberus company ), the German side led the Atlantic battle almost exclusively as a submarine war .

Background and preparation

As a result of the provisions of the Peace Treaty of Versailles after the loss of World War I , the German Reich was generally prohibited from owning submarines , as was the development and construction of aircraft carriers . Most of the political groups in the Weimar Republic supported a revision of this treaty. The NSDAP under Adolf Hitler , which came to power in 1933 , was no exception and ruthlessly went about its implementation. Massive rearmament began as early as 1933 . According to the fleet replacement plan adopted in 1934, the construction of an aircraft carrier and several large warships was commissioned, with an optimistic assessment of the diplomatic climate. Their size and number have been corrected upwards several times. The German-British fleet agreement of 1935 relaxed the restrictions of the Versailles Treaty and officially allowed Germany to build a submarine fleet.

The argument for the need to expand the fleet beyond the stipulations of the Versailles Treaty was the demand for a balance with the naval forces of France ( parity ). The conclusiveness of this demand was always controversial, because the likelihood of a sea war with France was only hypothetical due to the long common border that made land war possible. The urge to expand the fleet had its justification in the need of an aspiring great power to command a significant navy. The model for this was provided by Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz , who from around 1897, with the unrestricted support of Kaiser Wilhelm II, pushed for the establishment of a German deep-sea fleet . In contrast to the German Kaiser before the First World War, Hitler was reserved about this project. But Admiral Raeder, as Commander-in-Chief of the Navy, knew how to protect the interests of the Navy through regular visits to Hitler. As early as 1934, after a meeting with Hitler, Raeder made a note that England might be a future enemy. Until the spring of 1939 it was officially emphasized that the Royal Navy was out of the question as an opponent for the Navy due to its superiority.

| Great Britain | France | Germany | United States | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aircraft carrier | 8th | 2 | 0 | 6th |

| Battleships | 15th | 9 | 0 | 15th |

| Battle cruiser | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Armored ships | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Heavy cruisers | 15th | 7th | 2 | 18th |

| Light cruisers | 49 | 12 | 6th | 19th |

| destroyer | 201 | 71 | 22nd | k. A. |

| Submarines | 38 | 76 | 57 | 90 |

As a result of the naval agreement, armaments expenditures for the navy doubled in 1935, but their growth up to 1938 remained significantly behind those of the army and the air force . So it was not the armaments agreement, but rather the efficiency of German armaments and the distribution of raw materials to them that determined the strength of the German navy at the beginning of the war.

The Z-Plan fleet expansion plan , which provided for the construction of a large battle fleet and four aircraft carriers, did not receive Hitler's placet until January 1939. At the beginning of the war, the Navy had several larger surface warships and a submarine fleet (as well as sea rescue planes and sea scouts ); however, the implementation of the Z-Plan had only just begun. Only the keels of the additional battleships had been laid in the short time ; construction work on them was stopped immediately when the war broke out. Of the planned aircraft carriers, only one ( Graf Zeppelin ) was nearing completion, but this was repeatedly delayed in favor of submarine production due to the course of the war and ultimately never took place.

Except for the Royal Navy and the French Navy , the German Navy faced no equal opponents in Europe in 1939. Compared to the Kriegsmarine, the Royal Navy neglected the expansion of the submarine weapon. Instead, like the US Navy and the Japanese Navy , it pushed the use of aircraft carriers.

aims

The operations of the German navy in the Atlantic were initially characterized by individual operations on large surface warships and submarines. When companies Weserübung , the conquest of Denmark and Norway in the spring of 1940, almost all the forces of the German navy were involved. While the conquest was successful, the Navy was already having difficulty in meeting the Royal Navy.

From the western campaign in 1940 , the naval war focused on the supply routes of the British Isles . The only opponent left in the west was to be forced to surrender by cutting off vital supplies after the unsuccessful air battle for England and threat of invasion. Winston Churchill admitted he had doubts about England's survival in 1941.

Operations of German surface warships

Admiral Graf Spee's raid from September to December 1939

On August 21, 1939, the ironclad Admiral Graf Spee left Wilhelmshaven to take a waiting position in the Atlantic south of the equator. On September 26th, it was ordered to attack Allied merchant ships. From September 30th to December 7th, the ship sank a total of nine British merchant ships with a total of 50,089 gross tons in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

On December 13, 1939, the Admiral Graf Spee met an opposing ship formation in front of the mouth of the Río de la Plata , consisting of the British heavy cruiser HMS Exeter , the British light cruiser HMS Ajax and the New Zealand light cruiser HMNZS Achilles . In the course of the battle, HMS Exeter , which operated from the two light cruisers, was severely damaged (61 dead and 23 wounded) and put out of action. The two light cruisers, but also the Admiral Graf Spee , received damage and broke off the engagement to enter Montevideo . This naval battle also went down in Allied naval history as the Battle of Honor .

Due to political pressure on Uruguay from Great Britain, the ship had to sail again without the necessary repairs being carried out. To prevent the crew from making senseless sacrifices, the Admiral Graf Spee was sunk by its own crew on December 17th in the mouth of the Río de la Plata. The responsible sea captain Hans Langsdorff died shortly afterwards by suicide .

Operation Weser Exercise from April to June 1940

- Note : In some German-language publications, the Weser Exercise company is viewed as the dividing line between the First Atlantic Battle and the Second Atlantic Battle . In English-language publications, the term First Battle of the Atlantic (English. First battle of the atlantic ) related to naval warfare in World War I, the Second Battle of the Atlantic (English. Second battle of the Atlantic ) to naval warfare in World War II .

The naval war command had put together a total of eleven warship groups for the Weser Exercise company , the first five of which were intended for the conquest of Norway. The Warship Group 1 destined for Narvik consisted of ten destroyers. 200 mountain troops of the 38th Mountain Infantry Regiment were embarked on each of the destroyers . The Warship Group 2 destined for Trondheim was composed of the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper and four destroyers. The warship Groups 1 and 2 participated in the April 7, 1940 at 3:00 am under the protection of the battleships Gneisenau and Scharnhorst from the German Bight common drive north on. It was the largest naval unit that the Navy was able to assemble for an offensive operation in the course of the Second World War.

On the march north, the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper sank the British destroyer HMS Glowworm on the morning of April 8 .

The warship Group 1 reached on schedule Narvik . The coastal armored ships Eidsvold and Norge were torpedoed and sunk in front of and in the port basin of Narvik by the destroyers Z 21 Wilhelm Heidkamp and Z 11 Bernd von Arnim . The Scharnhorst and Gneisenau , heading northwards from the coast for remote security , met the British battle cruiser HMS Renown here . With only six heavy guns inferior in the rate of fire, Renown was able to keep the German ships at a distance thanks to the greater range of its 381 mm guns and escaped without being hit. The Gneisenau got a direct hit in the artillery control center on the Vormars platform. The German ships broke off the battle and returned to Wilhelmshaven a few days later .

After a battle broke out in the Ofotfjord on April 10 , in which the destroyers Z 21 Wilhelm Heidkamp and Z 22 Anton Schmitt sank and the British themselves had lost the destroyers HMS Hardy and HMS Hunter , the British returned three days later Reinforcement back. On April 13, 1940, there was a battle with a British naval formation, which consisted of the battleship HMS Warspite and nine destroyers. All eight German destroyers were lost. They had not been able to start the march back in time because the fuel takeover took too long. With no way of evading the attacks, they used all their ammunition and torpedoes and eventually had to be abandoned. Some British destroyers were damaged.

A Fairey Swordfish launched from the HMS Warspite catapult sank the German submarine U 64 . An attack by U 25 against the British unit on April 13, 1940 and another attack by U 25 and U 48 in Vestfjord against the battleship HMS Warspite on April 14, 1940 failed due to torpedo failures. On April 14, 1940, the heavy cruiser HMS Suffolk sank the German supply tanker Skagerrak (6,044 GRT) northwest of Bodo .

The warship group 3 consisting of the light cruisers Köln and Konigsberg and several smaller vessels could successfully in Bergen and Stavanger prevail. Likewise, the warship group 4 with the light cruiser Karlsruhe in Kristiansand .

The warship group 5 consisting of the heavy cruisers Blücher and Liitzow , the light cruiser Emden and several torpedo boats, during breakdown was due to the over 100 kilometer Oslofjord of coastal batteries fired. The Blücher received several gun and torpedo hits and sank east of the island of Askholmene. The Norwegian mine-layer Olav Tryggvason sank the German clearing boat R 17 . The Norwegian torpedo boat Aegir sank the German supply freighter Roda (6,780 GRT) and was sunk by an air raid.

On the morning of April 10th, the ships of the combat group entered the port of Oslo . It was not until June 10, 1940 that the Norwegian High Command signed the document of surrender, and some of the population switched to active and passive resistance to National Socialism .

Operation Juno in June 1940

On June 4, 1940, the battleships ran Scharnhorst and Gneisenau , the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper and the destroyers Hans Lody , Hermann Schoeman , Erich Steinbrinck and Karl Galster of Kiel from the operation Juno. The association, which thus consisted of practically all ships in the German fleet that were still operational, was supposed to relieve the hard-pressed German troops in Narvik by attacking troop convoys and the port of Harstad. On June 8th the ships were at the height of Harstad (Northern Norway). Here they met the retreat convoy of the remaining British troops from Norway. The Admiral Hipper sank with their destroyers the U-hunters Juniper , the large tanker Oil Pioneer and troop transport Orama . After that, the German association separated. The Admiral Hipper ran with the destroyers to Trondheim . Scharnhorst and Gneisenau stayed in said sea area, where they finally sank the aircraft carrier Glorious and its accompanying destroyers Acasta and Ardent . The Scharnhorst received a hit from a torpedo that had been shot down by the Acasta , which had already been badly hit . This hit the Scharnhorst in the area of the aft 28 cm turret , the mechanics of which was damaged, which meant that it was canceled for further operations.

On June 20, the Admiral Hipper and the Gneisenau were supposed to disrupt the British withdrawal movements. This mission ended at the fjord exit from Trondheim. Here the Gneisenau was torpedoed by the British submarine Clyde . Both ships returned to Trondheim. On July 25, the Admiral Hipper left for the trade war in the North Sea , while the Gneisenau returned to Kiel. A Finnish freighter was raised as a prize on August 1st. Over the next few days, the cruiser operated unsuccessfully in the Barents Sea . Eventually the Admiral Hipper was ordered back to Germany. On August 10, the ship went to the shipyard.

Admiral Scheer's cruiser war from October 1940 to April 1941

On October 23, 1940, the sister ship of the Admiral Graf Spee , the armored ship Admiral Scheer, left Gotenhafen and went to Brunsbüttel , which was the starting point for the upcoming long-distance operation. When she left there on October 27th, after a short stay in Stavanger, she managed to pass the Denmark Strait unnoticed and to reach the North Atlantic on November 1st.

There she came across the convoy HX 84 going from Halifax, Canada to England five days later and sank the freighters Trewellard (16 dead), Fresno City (1 dead), Kenbane Head (23 dead), Beaverford (77 dead) and Maiden from it (91 dead). It came to a battle with the auxiliary cruiser Jervis Bay , whose resistance enabled the majority of the convoy to escape, while he himself was defeated and perished in this unequal battle.

In mid-December, the Admiral Scheer was operating in the South Atlantic , and in February she advanced into the Indian Ocean as far as the Seychelles . Then she started the march back and entered Kiel on April 1, 1941. On this mission, the Admiral Scheer had covered around 46,000 nautical miles in 155 days. 17 ships with over 113,000 GRT were sunk. For the Allies it was the single operation with the highest losses by a German surface warship.

Enterprise Berlin from January to March 1941

Together with her sister ship Gneisenau , the Scharnhorst ran out of Gotenhafen (today: Gdingen) on January 22, 1941 for an Atlantic company. An attempt to break through the Faroe- Iceland Passage failed and the German ships withdrew to the east. After an oil takeover, it was possible to get into the Atlantic a few days later through the Denmark Strait.

The Scharnhorst was able to sink eight ships with around 50,000 GRT in the next few weeks ; the Gneisenau about 65,000 GRT. Convoys secured by British battleships were avoided as ordered. On March 22, 1941, both ships entered Brest .

Operation Rhine exercise in May 1941

To increase the pressure on the supplies to the British Isles and to support the submarine war, a squadron left Gotenhafen in May 1941 with the aim of the Atlantic. It consisted of the new battleship Bismarck , the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen and the destroyers Z 10 Hans Lody , Z 16 Friedrich Eckoldt and Z 23 , which stayed behind in Norway. The operation was given the code name Rhine Exercise . The Bismarck was also supposed to attack convoys that were secured by Allied battleships.

The squadron was sighted by the Swedish aircraft cruiser Gotland , which informed the British with a short radio message . The two capital ships were finally discovered in the Norwegian Krossfjord near Bergen by a reconnaissance aircraft of the type Supermarine Spitfire . The fleet chief on board the Bismarck , Admiral Günther Lütjens , intended to break through the Denmark Strait between Greenland and Iceland into the Atlantic. On May 24th, there was a battle with two British capital ships in the Denmark Strait. The battle cruiser Hood was hit several times, which then exploded and sank. 1,418 men died in the explosion, only three survived. The battleship Prince of Wales , which was also badly hit, withdrew.

Since the Bismarck was damaged and lost fuel, she should return to the port of St. Nazaire , which was occupied by the Navy, and have the damage repaired. The Prinz Eugen was at 18:34 command, independent trade war to lead and was discharged. The cruiser added fuel to the tanker Spichern in order to start the trade war on May 26, but had to refrain from further operations a short time later as damage to the propulsion system occurred. The ship then headed for the port of Brest, which it reached unmolested on June 1.

On May 27, 1941, the Bismarck was attacked again. A hit in the steering gear made it impossible to maneuver and sank - after being severely damaged in the ensuing battle - probably by self-detonation. 114 crew members of the Bismarck were rescued from British ships, and a further six of the total of 2,106 men were rescued by German submarines.

Operation Rainbow from December 1942 to January 1943

Together with the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper and several destroyers, the ironclad Lützow attacked the British Northern Sea Convoy Convoy JW 51B east of Bear Island. The Admiral Hipper was supposed to lure the escorts away from the convoy while the Lützow attacked and sank the defenseless merchant ships.

The project failed due to the extremely poor visibility. The Lützow drove past the convoy at a distance of two to three nautical miles, while Admiral Hipper was chasing the escort . The opening of fire on the convoy did not take place, however, because people on the Lützow believed they had their own ships in front of them. The destroyer Friedrich Eckoldt mistakenly headed for the cruiser Sheffield and was sunk by it. On the British side, the destroyer Achates and the minesweeper Bramble were sunk.

The importance of the allied aircraft carrier

A total of 32 escort aircraft carriers and 24 fleet aircraft carriers of the Royal Navy, and 121 escort aircraft carriers and 36 large aircraft carriers of the US Navy were deployed in various theaters of war . This strength of 213 aircraft carriers on the Allied side was due to the ability to increase production in the American arms industry. From 1935 to 1938, the armaments expenditures of the USA and Great Britain together corresponded to the equivalent of four billion US dollars, the armaments expenditures of the German Reich amounted to the equivalent of 12 billion US dollars, three times as much. In 1941, the two allies invested 13 billion US dollars in the armaments industry, more than twice as much as the German Reich with the equivalent of 6 billion US dollars.

The carriers in the Atlantic had the greatest importance in the area of submarine warfare. No large German surface warship was sunk by aircraft from an aircraft carrier. The great challenge for the Allied naval forces was securing convoy trains. This included the formation of Hunter Killer Groups , an association consisting of an escort aircraft carrier and several destroyers. These associations could also track a submarine beyond the immediate vicinity of a convoy and fight it from the air and water until it was destroyed.

31 submarines were sunk by carrier-based aircraft of the Royal Navy, which were grouped under the Fleet Air Arm (FAA), and 83 of the 250 submarines destroyed by aircraft were by US Navy aircraft. Admiral Dönitz noted in a memorandum of June 8, 1943: “The enemy's successes increased so much that the enemy aircraft is the most dangerous enemy of our submarines. The crisis in the submarine war (note: 38 submarines lost in the previous month) is therefore a consequence of hostile air domination in the Atlantic. "

Submarine war

Initially, submarines could cause heavy losses to the convoys and the Royal Navy. In the course of the war the situation of the navy became hopeless due to the development of radar and other technical innovations for submarine location - not least due to the deciphering of maritime radio traffic by British cryptanalysts . While the losses measured by the sunk gross registered tons of Allied merchant ships of 5.7 million GRT were still considerable, the losses fell to 1.6 million GRT in 1943, and in 1944 175,013 sunk GRT were still to be complained about.

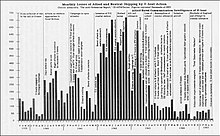

In relation to the losses of Allied ships per month, June 1942 represents the high point with 124 merchant ships with over 600,000 gross tons. While half a million GRT were sunk in March 1943, the turn in favor of the Allies took place by May 1943. By the end of the year, 150 Navy submarines had been sunk.

Factors of battle

Lending and Lease Act

On February 18, 1941, the United States Congress passed the Lending and Lease Act , which allowed the United States to provide Great Britain with armaments such as urgently needed destroyers and escort aircraft carriers for fighting submarines without paying cash. From the US entry into the war in December 1941, US Navy units under the command of Admiral Ernest J. King actively participated in the escort in the Atlantic. The war against the German Empire was given precedence over the war against Japan as it was viewed as the more dangerous opponent.

Deciphering the marine code

Even before the attack on Poland , Polish cryptanalysts handed over two copies of the Enigma key machine to the astonished British secret service at the legendary Pyry meeting . As a result, the encrypted radio messages between the control centers of the air and naval forces were intercepted. Although the encryption methods were changed several times during the war, the British secret service succeeded time and again in closing these loopholes and deciphering the German radio messages . In May 1941, for example, an Enigma M3 machine with the associated code tables was salvaged from the sinking submarine U 110 by the British destroyer HMS Bulldog . The commander of the submarines , Admiral Karl Dönitz , stated that despite suspicions he only learned of this fact after the war. This fact was not officially confirmed by the Allies until the 1970s.

The position information of the submarines obtained under the code name Ultra contributed significantly to their successful combat. The Kriegsmarine only operated between February and December 1942 under a procedure of the newly introduced version Enigma-M4 that was not broken by the Allies . Pinch of keys and code books ( weather code and short signal booklet ) from U 559 by Tony Fasson , Colin Grazier and Tommy Brown from HMS Petard on October 30, 1942.

Maritime reconnaissance flights

Both the Allied Air Force and the Navy carried out reconnaissance flights with various sea reconnaissance planes wherever possible. The main task of the airplanes of the Kriegsmarine was to track down convoys and then bring in submarines or land-based bombers . Some aircraft were even equipped with a small bomb load and could attack individual ships or poorly protected convoys independently. With the increased use of Allied escort aircraft carriers, the losses from Allied fighters increased dramatically.

In particular, the operations with armed long-range reconnaissance aircraft of the type Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor caused losses to the convoys, which is why Churchill described them as the "scourge of the Atlantic". Until March 1941, the ratio of the sunk tonnage between submarines and long-range combat aircraft was ten to one (2,720,157 GRT by submarines, 272,485 GRT by airplanes). From April 1941 to December 1941 this ratio worsened to 20: 1 (1,582,389 GRT by submarines, 79,677 GRT by airplanes).

The Allied planes had the task of finding enemy units - especially submarines - and disrupting their activities. The bombers used could also attack larger formations, with single-engine torpedo planes also being used from aircraft carriers during the fight against the Bismarck . The British Coastal Command began to equip aircraft with depth charges for anti-submarine warfare in 1940 , later on-board radars were added. The US Navy was supported by USAAF long-range land-based bombers . From 1939 to 1940 only two submarines were lost to air raids. By the end of the war, more than 250 German submarines had been sunk by Coastal Command, USAAF and other allied air forces, including the carrier-supported units of the US Navy and the FAA.

Detection methods

The most common method of detecting submarines at the beginning of the war was the use of sonar (sound navigation and ranging), which the Royal Navy called ASDIC (Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee, founded in 1917 for the research and testing of sonar).

In addition, both German research and the Allies had extensive theoretical knowledge of the possible uses of electromagnetic waves. As early as 1939, the Kriegsmarine used a fire control system in the weaponry version that worked with radio measurement technology (code name Seetakt ). The armored ship Admiral Graf Spee , equipped with sea clock , was sunk itself not least to prevent this technology from falling into the hands of the enemy.

On the Allied side, technology was increasingly directed towards the location of aircraft and submarines.

A related method did not work actively (i.e. it did not emit its own beams), but rather passively by locating radio sources, the Royal Navy using the expression Huff-Duff (from: HF / DF, High Frequency Direction Finding , German: Kurzwellenpichtung) has been. A large number of German submarines, which radioed their location reports to the headquarters in France, unintentionally revealed themselves to their pursuers.

From 1942 onwards, MAD (Magnetic Anomaly Detection) was a new type of procedure that measures and interprets changes in the earth's magnetic field for hunting submarines from airplanes.

Combined use forms such as the use of a particularly efficient headlamp ( Leigh Light ) and radar from aircraft or the sonar controlled water bomb thrower brought further improvements. With the noise-sensitive Mark 24 mine ("wandering Annie"), a target-seeking torpedo was used from May 1943, with the help of which 38 submarines were sunk by the end of the war.

The ultimate success in the submarine hunt brought the cooperation of several units, each of which compared their measurements with each other. By converting large warships and merchant ships into special escort aircraft carriers, Hunter-Killer-Groups (German: Jäger-Destörer-Gruppen) were able to operate extremely effectively in the vicinity of convoy trains. With this technology, the freedom of movement of the slow submarines was so restricted by May 1943 that Dönitz ordered them back to their bases. From then on, there were mainly little promising individual actions.

Aftermath and outcome

Between 1939 and 1945, 36,000 sailors from the merchant and navy were victims of the war on the Allied side. Over 5,000 Allied ships were sunk, 175 of them were warships (20.3 million gross tons, of which 14.3 million GRT by submarines).

In contrast, the German navy lost over 30,000 sailors, 783 submarines and almost all larger surface warships, even if most of them were withdrawn from the Atlantic theater of war and sunk elsewhere from 1941 onwards. Of the 40,000 trained German submarine crews, 27,000 perished. The German navy was closest to its primary goal - the isolation of England - in 1941 before the USA entered the war.

The economic efficiency of the German Reich was totally overwhelmed with the waging of a six-year sea war. The Commander-in-Chief of the Navy, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, who was responsible at the beginning of the war , knew this and commented on the strength of the fleet that the Navy could only "die with decency" in the fight against England. Raeder, insulted in his honor after the failures of the surface warships by Hitler, was replaced by Dönitz as Commander-in-Chief of the Navy at his own request in January 1943.

The Royal Navy also saw a change in leadership in 1943 when the First Sea Lord Sir Dudley Pound was replaced by Andrew Cunningham on account of illness in September of that year . Pound died in October 1943.

As the war progressed, the ruthlessness of waging war on all sides increased. While singled to prize regulations was fought, soon broke unrestricted naval warfare. An order from Admiral Dönitz not to help the castaways of the attacked ships ( Laconia order ) led to treatment at the Nuremberg Trials in 1946. Dönitz was exonerated on this point by Admiral of the US Navy Chester Nimitz , who made it clear that the Allies were Submarines had operated in the Pacific under similar instructions.

Feature films

- Wolfgang Petersen : The Boat (1981)

- Jonathan Mostow : U-571 (2000)

- Uwe Janson : Laconia (2011)

- Aaron Schneider : Greyhound - Battle of the Atlantic (2020)

literature

- Lothar-Günther Buchheim : U-boat war. Piper, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-492-02216-2 .

- Jochen Brennecke: hunters - hunted. German submarines 1939–1945. Heyne, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-453-02356-0 .

- John Costello, Terry Hughes: Battle of the Atlantic. Bastei Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1995, ISBN 3-404-65038-7 .

- Michael Hadley: The Myth of the German Submarine Gun. Mittler & Sohn, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-8132-0771-4 .

- Stephen Harper: The Battle for Enigma - The Hunt for U-559 . Mittler, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-8132-0737-4 .

- David Miller: German U-Boats up to 1945. Motor book, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-7276-7134-3 .

- VE Tarrant: West course. Motorbuch, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-613-01542-0 .

- Dan van der Vat: Battlefield Atlantic. Heyne, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-453-04230-1 .

- Jürgen Rohwer : The war at sea. Flechsig, Würzburg 2004, ISBN 3-88189-504-3 .

- Percy E. Schramm (ed.): War diary of the OKW. 8 halves. Weltbild, Augsburg 2005, ISBN 3-8289-0525-0 .

- Richard Overy: War and Economy in the Third Reich. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1995, ISBN 0-19-820599-6 .

- Guido Knopp: The War of the Century. Ullstein, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-548-36459-4 .

Web links

- Atlantic Battle ( Memento from February 5, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) in ZDF Zeitgeschichte

- uboat.net (English)

- Chronicle of the Naval War 1939–1945 - detailed chronology, compiled by Jürgen Rohwer (military historian)

Individual evidence

- ^ Chaz Bowyer: History of the RAF. Hamlyn, London 1977, OCLC 04034840 , p. 158.

- ↑ Not to be confused with this operation with the codeword rainbow . When issued at the end of the Second World War, the code word rainbow was intended to trigger an order for the German submarine weapon. This order was aimed at the submarines being scuttled by their crews.

- ^ David Kennedy: Freedom from Fear - The American People in Depression and War. Oxford 1999, pp. 571, 589.