German occupation of France in World War II

The German occupation of France after the western campaign began with the armistice of June 22, 1940 . The Forces françaises libres and General de Gaulle continued the fight with the support of the Allies . In 1944 he finally formed the Provisional Government of the French Republic . The occupation ended with the surrender of the German troops on the occasion of the liberation of Paris on August 24, 1944.

The German conquest of Paris in France on June 16, 1940 resulted in the replacement of the Reynaud government by the Pétain government , which declared that a continuation of the Second World War was hopeless on the French side. She closed on 22 June 1940, Nazi Germany the Armistice of Compiègne . This divided the French territory into an occupied and an unoccupied zone. A German military administration under a military commander in France with headquarters in Paris , General Otto von Stülpnagel , was subordinate to northern and western France with the important industrial areas in the north as well as the entire canal and Atlantic coast up to the Spanish border. The northern departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais were subordinated to the German military commander , General Alexander von Falkenhausen , based in the Belgian capital, Brussels . The territory of the realm of Alsace-Lorraine , which Germany had to cede to France in the Peace Treaty of Versailles in 1919 , was subordinated to the Gauleiter of the Reichsgaue Baden and Saarpfalz as CdZ areas " Alsace " and " Lorraine ". In the unoccupied south of France, the seaside resort of Vichy in the Allier département was the seat of the new French government from July 1940 with the head of state and Prime Minister Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain. About 40 percent of the French national territory including the colonies as well as a 100,000-strong volunteer army, a significant part of the navy, which had withdrawn into the ports of the Mediterranean and the colonies, and a small air force were subject to the Vichy regime .

In addition to the military administrations, other organizations with special powers such as SS and police leaders were installed in the occupied part of France during the occupation .

The Vichy regime quickly developed a policy of collaboration with the Germans in the fight against the French resistance, the Resistance , and, like German authorities in the northern zone, also carried out a persecution of the Jewish population in the unoccupied southern zone. She was deported to Germany and Poland . This constellation was reinforced after the Allies landed in November 1942 in French North Africa ( Morocco and Algeria ). Because the French were reluctant to oppose this invasion, southern France was also occupied by the military. Officially, the Vichy government remained sovereign. However, the newly occupied area was placed under a German "Commander Heeresgebiet Südfrankreich" and the French army was disarmed.

Background of the partial cast

There were compelling reasons for the Nazi state to favor a remaining French state - the Vichy regime - which was not under its direct influence. In order to bring Great Britain to its knees as the only viable enemy by an invasion - the Sea Lion Company - or by cutting off the sea routes, the Channel and Atlantic coasts had to be occupied. An obstacle to the goals of German warfare and foreign policy were the Italian claims that Benito Mussolini tried to enforce. He viewed the Mediterranean as “mare nostro”, meaning sea of Italy, and insisted on keeping the western Mediterranean free from German troops. He wanted to annex Tunis . That would have sabotaged the German plan to win Philippe Pétain over to the Axis powers ; the new head of state was bitter about the British behavior during the western campaign , especially in the latter phase. Mussolini's plans would have favored Theodore Roosevelt junior's endeavors to keep France at war, with reference to the later entry of the USA to further resistance against Germany, and to realize the Franco-British union offered by Winston Churchill . An unoccupied territory, on the other hand, could further weaken the French propensity to get involved. Then there was Pétain's pride: the marshal refused to take his seat of government in an occupied part of France.

Italy's role in this situation is marked by Mussolini's behavior; He wanted to demonstrate his supremacy in the Mediterranean and invaded Greece from Albania in October 1940 without informing the German side. The "Duce" created a situation that threatened the Romanian oil region of Ploieşti for Germany and was therefore extremely dangerous: British troops that Athens had not yet allowed into the country landed on Greek territory. This in turn forced the German leadership to embark on the Balkan campaign (1941) , which threw all plans upside down and only came to a temporary end with the airborne battle over Crete . The start of the Barbarossa company was thus delayed by around four weeks.

Germany absolutely wanted to prevent the strong French Mediterranean fleet from joining the British naval forces after a German occupation of its European bases . Admiral François Darlan's plans for this case provided for the units lying in Toulon to move to French North Africa , then to split off the French colonies politically and to join the British. Only the British attack on the French fleet in Mers-el-Kébir, with many dead, made this German concern irrelevant. After the Allies landed in North Africa in autumn 1942, Germany and Italy moved into the unoccupied part of France; because now the European southern flank had to be protected, which Marshal Pétain neither could nor wanted.

Organization and objectives under German occupation

While in the occupied part of France the command staff in the military administration commanded the German occupation troops, the administrative staff controlled the French administration. The aim of the Germans was a form of occupation with a minimum of military and administrative effort, which required the willingness of the French administrative authorities and, last but not least, a large part of the French population to work smoothly with the German occupiers. In fact, a relatively small apparatus of 1,200 civil servants and officers was sufficient for the German military administration to govern the occupied part of France and to secure the industrial and agricultural supplies urgently needed by the German Empire for the conduct of the war. In the long term, a functioning French economy should be integrated into a large economic area that Germany is aiming for and dominating.

In order to relieve the German war economy , French companies were increasingly assigned orders from the German side during the Second World War , and France's economic power was almost completely adjusted to the needs of the German Empire. The cost of the occupation was claimed from France, which had to pay 20 million Reichsmarks daily. The occupation costs, which the Germans deliberately overestimated, made the greatest burden on the French state budget, which was not offset by corresponding tax revenue.

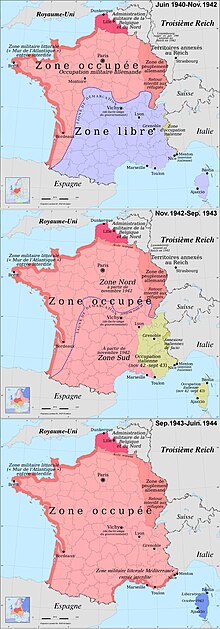

Demarcation Line and Zones in France (1940-1944)

The Franco-German armistice led to the separation of France into two main zones. The "occupied zone" comprised the areas occupied by the German Wehrmacht, as well as the "free zone", which was popularly known as the "nono zone" (nono for "non occupée" - not occupied). The approximately 1200 km long demarcation line began on the Spanish border near Arnéguy in the Basses-Pyrénées (Pyrénées-Atlantiques) department, then passed through Mont-de-Marsan , Libourne , Confolens and Loches and ran to the north of the Indre department, where it was branched off to the east and, after crossing Vierzon , Saint-Amand-Montrond , Moulins, Charolles and Dole, ended at Gex on the Swiss border.

Occupied Zone (North Zone)

This zone occupied by the Germans was under the command of the military governor of Paris, General Otto von Stülpnagel , and comprised approximately 55% of the territory. This was renamed the North Zone in November 1942, when the Germans also occupied the free zone.

Free zone (south zone)

On July 2, 1940, the French government established itself in the city of Vichy. This made Vichy, in a sense, the capital of the free zone. On July 10, 1940, Parliament transferred full powers to Marshal Pétain. This proclaimed the "French state" and a little later began a policy of collaboration with the German occupiers. After the German occupation of Vichy France in November 1942, the free zone was renamed "South Zone".

Other special zones

Reserved zone - from the Somme estuary to the Rhône

The French generally referred to the reserved zone as the “forbidden zone”, as they could only enter this area with considerable difficulty (increased controls, along the Channel coast and along the Franco-Swiss border).

Italian occupied zone - from Lake Geneva to the Mediterranean

This zone extended from Lake Geneva to the Mediterranean. It runs east of Chambéry , Grenoble and Gap up to and including Nice. However, the Italians actually only occupy a few points in this area.

Prohibited zone - the construction of the Atlantic Wall

In the autumn of 1941 a forbidden zone was created along the canal and Atlantic coast, a foretaste of the construction of the Atlantic Wall . Only people who had been resident in this area for at least three months, personnel who worked for the German army and railway personnel could enter and move around in this zone. In addition, it was forbidden to telegraph or make phone calls.

Administrative areas during the occupation

The occupied north was annexed to the military district of Belgium (seat of the military commander in Belgium), the occupied east was divided into five different administrative areas and incorporated into the German Reich, as well as a military administration (seat of the military commander in Paris).

- Paris (Greater Paris)

- District A ( Saint-Germain-en-Laye )

- District B ( Angers )

- District C ( Dijon )

- Bordeaux district

A field command and district command offices were installed in each administrative district.

Occupation troops, security police and SS

The occupation troops in France comprised around 50,000 men.

Feldgendarmerie and Geheime Feldpolizei (GFP) were stationed in police stations in the respective departments and had intelligence services in the district capitals.

As of June 1940, SS-Standartenführer Helmut Bone was delegated to France as the chief of the security police and the SD and remained so until September 1944. After the Night and Fog Decree , people suspected of the resistance were deported to Germany from December 1941 and sentenced there or taken to concentration camps. Together with his superior, the Higher SS and Police Leader Carl Oberg , and his deputy, KdS (Commander of the Security Police) Kurt Lischka , he enforced the deportations of French Jews and Jews of other nationalities to German extermination camps in Paris .

In view of the increasing resistance, the executive apparatus in France was reorganized in 1942. The secret field police (GFP), which had been subordinate to the military commander, was replaced and its tasks were transferred to the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA). Helmut Bone remained in command of the Security Police (BdS) for occupied France. The Higher SS and Police Leader (HSSPF), SS-Obergruppenführer Carl Oberg took over the management of Office VI of the Security Service (SD) in Paris on June 1, 1942.

From this point on, the Gestapo was ubiquitous in France. The so-called Jewish advisor Theodor Dannecker started the deportations.

Economic situation and imbalance

The line of demarcation created an imbalance between the north and south of the territory. By cutting up or restructuring French territory after the armistice, the German occupation secured the richest industrial areas and the entire Atlantic coast.

Due to a lack of raw materials , which were “confiscated” in favor of the German economy , industry and agriculture in the southern zone were severely hampered, if not completely paralyzed. The situation was particularly difficult in the border region, as businesses were cut off from their labor and farmers from their fields. Due to higher prices in the northern zone, smuggling and the black market developed despite all control measures introduced. Difficulties in supply increased the risk of famine.

Just like the movement of people, the movement of goods was subject to approval by the German authorities. In May 1941, there was some relief when Darlan, in exchange for consideration in Syria, succeeded in restoring the movement of goods and values, especially from the unoccupied to the occupied zone. Despite some shortages in energy, raw materials and labor, the economy slowly recovered, only to deteriorate again between 1942 and 1943 and collapse completely in 1944. In February 1943 the Germans lifted the demarcation line because they had been occupying all of French territory since November 1942.

However, this line did not disappear from the maps of the German General Staff, and some restrictions remained, especially in the movement of goods. Since the French threatened to reintroduce the demarcation line until the end of the war, it remained a means of pressure for the German occupiers until 1944.

Food shortages

Supply problems quickly affected daily life, and French shops soon ran out of goods. Faced with these problems, the government reacted by introducing food and meal stamps , with which one could get at least the most necessary food or products such as bread, meat, fish, sugar, fat and clothing.

Even tobacco and wine had to be rationed. Each Frenchman was categorized according to his personal energy needs, age, gender and occupation and was given the appropriate ration.

Long queues were a daily occurrence, especially in urban areas. Products like sugar or coffee have been replaced by substitutes. (Coffee with chicory and sugar with saccharin ). Merchants use this fact to their advantage and sell food on the black market without food and meal stamps at high prices.

Shortage of raw materials

In 1939, fuel consumption in France was around 3 million tons. After the armistice of June 22, 1940, France only had 200,000 tons of reserves. During the German occupation, among other things, the carburettors were set to be more economical, so that fuel consumption was around a quarter less than before the war.

Commitment payments

The Franco-German armistice agreement provided for the following provisions in Article 18: “The maintenance costs of the German occupation troops on French territory will be borne by the French government.” The daily commitment payments were set at 400 million francs . In January 1941 this payment obligation was reduced to 300 million francs, at the end of 1941 to 109 million francs.

In 1942, commitment payments totaling 285.5 billion francs were made to the German Reich. 109.5 billion for space costs, 6 billion for housing costs, 50 billion prepayment for cleaning and 120 billion other financial services expenses.

The continuation of the war

Despite the armistice, the war continued and the German Wehrmacht became an Allied target in France as well.

Allied bombing raids

Due to further bombing raids by the Allies after the armistice agreement of June 22, 1940, France was one of the hardest hit countries to mourn bomb victims. The bombing intensified during Operation Overlord in 1944 . In preparation for the planned invasion of Normandy on May 26, 1944, the Allied Air Force mainly attacked traffic routes in France. In the bombing of Lyon, Nice and Saint-Etienne, 3,760 people were killed in one day.

French bombing losses (1940-1945)

| year | dead | Injured | Destroyed buildings | Damaged buildings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | 3543 | 2649 | 25471 | 53465 |

| 1941 | 1357 | 1670 | 3265 | 9740 |

| 1942 | 2579 | 5822 | 2000 | 9300 |

| 1943 | 7446 | 13779 | 12050 | 23300 |

| 1944 | 37128 | 49007 | 42230 | 86498 |

| 1945 | 1548 | 692 | 300 | 800 |

Compulsory Labor Service (STO)

The compulsory labor service ( Service du travail obligatoire STO) was an organization for the recruitment of French skilled workers by the Vichy regime for use in the German war economy. The STO was founded in February 1943 after the previous organization Relève (French for replacement team, offspring) from 1942, which was also based on laws of the Vichy regime, had failed.

So were thousands z. B. employed at the Reichsbahn , which was one of the preferred targets of the tactical Allied bombing raids. Usually housed in barracks near repair works or railway junctions, numerous French workers also fell victim to the bombs when there was no space for them in the air raid shelters. For many young French people, the STO meant having to choose between forced labor in the German Reich and diving into the French underground, or even participating in the armed fighting in the Maquis. French forced laborers (like those of other nations) also took part in the active resistance against National Socialism. In France, the term has since been synonymous with the demand economy .

Collaboration and persecution of the Jews

The German authorities had three interfaces with their French employees:

- The military commander for occupied France (MBF) with his staff made up of Wehrmacht personnel and civilian experts resided in the Hotel Majestic in Paris . He was subordinate to the High Command of the Army (OKH) and, in addition to military and economic tasks, initially also had security-political tasks.

- Mainly political issues were dealt with by Ambassador Otto Abetz , who was subordinate to the German Foreign Office and thus Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop . He resided in the Palais Beauharnais .

- The third sphere of influence on the German side was under Heinrich Himmler : the members of the law enforcement and security police forces as well as the SD who were responsible for collecting news, for maintaining peace and order in cooperation with the French authorities, and for the registration and deportation of Jews and others undesirable ethnic groups were responsible.

A heavy burden for the regime is the partly voluntary willingness to cooperate with the German authorities in the registration, discrimination, arrest and deportation of Jews and other ethnic minorities persecuted by the Nazi regime to the extermination camps and the confiscation ( Aryanization ) of their property. So first in October 1940 and then in June 1941 “Statuts des juifs” (special laws for Jews) were introduced, even before the German authorities had even requested it.

Wearing the “Star of David” became compulsory in the occupied area. The Vichy regime did not protest against the introduction of the “yellow star” in the occupied zone and, for its part, had the Juif stamp stamped on identity papers. Between 1942 and 1944, 73,853 people declared to be Jewish (around a quarter of all Jews living in France) were deported to extermination camps; two thirds of them did not have French citizenship.

The French Resistance (The Résistance)

The Resistance in France came into being immediately after the German occupation and the armistice signed by Marshal Pétain with Germany on June 22, 1940. At first there were only a few thousand people who did not simply want to endure the German occupation. Their goal was the planned action against the occupiers. The Resistance was not organized and run uniformly, but pursued different goals in the interests of its sponsoring organizations. In the spring of 1943, Jean Moulin , an envoy from General de Gaulle, succeeded in defining the most important political groups, at least on general common goals, and in establishing a coordinating body. Against the swastika used by the Germans , the Lorraine cross was also adopted by the Resistance as a symbol of the French liberation struggle.

The activities of the Resistance included:

- Collection and transmission of information;

- Sabotage (railways, telephone lines, etc.);

- Killing of German officers and soldiers as well as employees;

- Logistic support for allied airmen and paratroopers;

- Organization of escape routes or border crossings (including the demarcation line);

- Production of forged documents.

The Resistance and its offshoots set up various organizations to help people cross the border into neutral countries or to hide in France or Benelux with false papers. Thousands of downed pilots were cared for and taken out of the country via networks like Komet . Jewish families and children were given shelter by French families, for example in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon . Young conscripts (so-called Malgré-nous ) from Alsace-Lorraine, who were considered to be Germans and who escaped forced German recruitment by fleeing to occupied or unoccupied France, and young French people who were threatened with deportation to forced labor or being obliged to do so, were supported partially recruited for active resistance.

See also

- Colonel-General Wilhelm Keitel - signatory of the armistice agreement for Germany

- General Charles Huntziger - Signatory of the Armistice Agreement for France

- Compiègne wagon - wagon No. 2419 in which France's capitulation to the German Empire was signed

- Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives “General Commissariat for Jewish Questions” - Authority of the Vichy regime

- Rafle du Vélodrome d'Hiver “Razzia of the Winter Velodrome” - Mass arrests in Paris carried out by French police on July 16 and 17, 1942

- Franco-German Relations - Reconciliation between Germany and France after the Second World War

literature

- Helga Bories-Sawala: French in the "imperial deployment". Deportation, forced labor, everyday life; Experiences and memories of prisoners of war and civilian workers. Lang, Frankfurt 1996, ISBN 3-631-50032-7 , (Dissertation University of Bremen, 3 volumes: 475, 696, 352 pages, 1995, 21cm).

- Helga Bories-Sawala, Rolf Sawala: “J'écris ton nom: Liberté!” La France occupée et la Résistance. Schöningh, Paderborn 2002, ISBN 3-506-45500-1 , (textbook).

- Harry R. Kedward: In Search of the Maquis. Rural Resistance in Southern France 1942–1944. 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1994, ISBN 0-19-820578-3 .

- Ludger Tewes : France during the occupation 1940–1943. The view of German eyewitnesses. Bouvier Verlag, Bonn 1998, ISBN 3-416-02726-4 .

- Ludger Tewes: Wehrmacht and Evangelical Church in Paris during the occupation 1940–1944. From: Theologie und Hochschule 5, Historia magistra 5. Ed. Jürgen Bärsch, Hermann-Josef Scheidgen , Gustav-Siewerth-Akademie, Cologne 2019, pp. 557–610, ISBN 978-3-945777-00-8 .

- Ernst Klee : The dictionary of persons on the Third Reich . Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-10-039309-0 .

- Walther Flekl: Resistance France Lexicon. Erich Schmidt, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-503-06184-3 , pp. 833-836.

- Eberhard Jäckel : France in Hitler's Europe. The German policy on France in World War II (= sources and representations on contemporary history, Volume 14). DVA , Stuttgart 1966, ISSN 0481-3545 (habilitation thesis 1966, 396 pages).

- Hermann Böhme: The Franco-German armistice in World War II. Origin and basis of the 1940 armistice . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1966.

- Andreas Stüdemann: The development of international mutual legal assistance in criminal matters in National Socialist Germany between 1933 and 1945. Lang , Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-631-59226-7 , p. 451.

- Julian Jackson: The Fall of France. The Nazi Invasion of 1940. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2003, ISBN 0-19-280300-X .

- Karl-Heinz Frieser : Blitzkrieg legend. The western campaign in 1940 (= operations of the Second World War. Volume 2). 3. Edition. R. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-56124-3 .

Web links

- Hitler Europe: France during the occupation , ahbon.free.fr, 9 November 2015 (newspaper clippings, French)

- Western campaign: How Hitler overran France 70 years ago. In: Welt online . May 10, 2010.

Individual evidence

- ^ German Historical Museum: The Second World War / Occupation Regime in France. dhm.de, November 5, 2015.

- ^ Serge Klarsfeld: Vichy - Auschwitz: The cooperation of the German and French authorities in the final solution of the Jewish question in France. Greno, Nördlingen 1989, ISBN 3-89190-958-6 .

- ↑ Philipp W. Fabry : Balkanwirren 1940/41. The diplomatic and military preparation of the German Danube crossing. Darmstadt 1966.

- ^ The Allied landing in North Africa ruined Vichy. In: The world. 2012.

- ^ Atlantic Wall in Southwest France: France under German occupation 1940–1944. Master's thesis . petergaida.de, November 5, 2015.

- ^ Arnulf Scriba: The German occupation regime in France. Lemo, accessed December 15, 2015.

- ^ Ludger Tewes: France in the Occupation 1940 to 1944: The View of German Eyewitnesses. Bouvier Verlag, Bonn 1998, ISBN 3-416-02726-4 .

- ↑ Peter Lieb : Conventional War or Nazi Worldview War - Warfare and Fight against Partisans in France 1943/44. Munich 2007, p. 63.

- ^ Bernhard Brunner: The France Complex. The National Socialist Crimes in France and the Justice of the Federal Republic of Germany . Wallstein, Göttingen 2004, p. 59.

- ^ Eberhard Jäckel : La France dans l'Europe de Hitler . Éditions Fayard, Paris 1968, p. 320 (German original edition: E. Jäckel: France in Hitler's Europe - German policy on France in World War II . Deutsche Verlag-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1966).

- ^ Andreas Nielen: Archives of the German military administration. The occupation of Belgium and France (1940–1944). ( Memento of September 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) ihtp.cnrs.fr, November 9, 2015.

- ^ Les Nithart: Rationing in France during the Second World War. Wars, economic crises and currencies . nithart.com (French), November 9, 2015.

- ^ German-French armistice agreement of June 22, 1940. (PDF; 1.2 MB) Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law 1940.

- ^ What was on May 26, 1944. Portal for the history of the 20th and 21st centuries, chroniknet.de, November 9, 2015.

- ↑ Richard Overy : The Bomb War. Europe 1939 to 1945. Rowohlt Verlag, 2014, ISBN 978-3-644-11751-8 .

- ↑ Ulrich Herbert : Best. Biographical studies on radicalism, worldview and reason. 1903-1989. 3. Edition. Dietz, Bonn 1996, pp. 254/232.

- ^ Bernhard Brunner: The France Complex: The National Socialist Crimes in France and the Justice in the Federal Republic of Germany . Frankfurt am Main 2008, p. 44.

- ↑ Katja Happe u. a. (Ed.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945. Volume 12: Western and Northern Europe, June 1942–1945. (Source collection), Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-486-71843-0 , p. 80.