Enigma-M4

The Enigma-M4 (also called key M , more precisely key M form M4 ) is a rotor key machine that was used in the Second World War from February 1, 1942 in the German Navy 's message traffic for secret communication between the commander of the U‑boats (BdU) and the German submarines operating in the Atlantic .

In contrast to the previously used Enigma‑M3 and the Enigma I used by the army and air force and the Enigma‑G used by the German secret services , the Enigma‑M4 is characterized by four rollers (apart from the entry roller and the return roller ). This means that its encryption is cryptographically significantly stronger than that of the other Enigma variants with only three rotors and could therefore not be broken by the Allies for a long time .

The word “Enigma” ( Greek αἴνιγμα ) means “ enigma ”.

prehistory

All parts of the German Wehrmacht used the Enigma rotor cipher machine to encrypt their secret messages . However, different models were used. While the army and air force almost exclusively used the Enigma I, there were different model variants of the Enigma‑M for the navy , which they usually referred to as the “Key M”. The main difference was the use of more reels than the Enigma I, where three reels could be selected from an assortment of five. This resulted in 5 × 4 × 3 = 60 possible roll positions of the Enigma I.

The Enigma-M1 , on the other hand, had an assortment of six different cylinders (identified with the Roman numerals I through VI), three of which were fitted to the machine. This increased the combinatorial complexity to 6*5*4=120 possible roll positions. With the Enigma‑M2 , the range of rollers had been increased by one more, so that 7·6·5 = 210 roller positions were now possible. And the Enigma-M3 , used by the Navy early in the war, had eight reels, three of which were used. The M3 thus had 8 7 6 = 336 possible cylinder positions. While the M1 to M3 models only ever had three rollers in the machine, the M4 had four rollers side by side in the machine. This significantly increased the cryptographic security of the M4 compared to its predecessors.

In order to be able to communicate secretly, the key machine itself represents the one important component. In modern language, transferred to a computer system , it is called the hardware . For full functionality, this must be supplemented by another component, in the case of computers it is the software or the algorithms implemented by it . In principle, instructions for action can be freely agreed between the sender and recipient in the case of a key machine. In the case of military use of the Enigma, the procedures for using the machines were regulated by relevant service regulations of the Wehrmacht . In the Navy there was the Navy service regulation M.Dv.Nr. 32/1 entitled "The Key M - Procedure M General". The key procedure to be used with the Enigma‑M4 was precisely defined here.

A particularly important part of the key procedure, in addition to correct operation, was the agreement on a common cryptological key . As with all symmetrical cryptosystems , the sender and recipient of an encrypted secret message not only had to have the same machine in the Enigma, but also had to set it up identically to one another. For this purpose, top-secret key boards were distributed to all authorized participants in advance . To ensure security within such a large organization as the Kriegsmarine, as with the army and air force, there were many different key networks, e.g. Aegir for surface warships and auxiliary cruisers overseas, Hydra for warships near the coast, Medusa for submarines in the Mediterranean , Neptun for battleships and heavy cruisers and Triton for the Atlantic submarines. There were other key nets. The Kriegsmarine initially only used the Enigma‑M3 for all of them.

However, the need to form a separate, specially secured key network for the units operating on the high seas was soon recognized . In October 1941, in a letter from the High Command of the Kriegsmarine (OKM) to the commander of the battleships , the "Keyboard Neptun" was introduced as a new key and the use of the Enigma‑M4 was ordered for this purpose. This happened four months before the M4 entered service for submarines. The key net of Neptune was never broken.

"The need to send messages to and from naval forces that operate in the North Atlantic for several weeks away from closer home waters , e.g. operations of the battleships Gneisenau , Scharnhorst , Tirpitz , Prinz Eugen , Admiral Hipper , is even more acute than before from the offices at home keeping it secret gives reason to use a separate key for the key M for such operations.

For this purpose, the following key means are used:

a) The key M form M4, the delivery of which with OKM Skl /Chef MND 5489/41 dated 07/05/41 the Stat. Kdos. was ordered. On OKM Skl/Chef MND No. 7283/41 dated 25.8.41 (not to BdS and BdK) is pointed out.

b) The key panel 'Neptune', which is hereby introduced as a new key.

The key 'Neptune' is only applicable to the key M form M4 (from test number 2802 onwards).”

construction

The structure of the Enigma‑M4 has some special features compared to that of the Enigma I. The main difference is the use of four rollers (rotors) compared to only three in the other models. The four reels were chosen from a total of eight plus two reels. A distinction had to be made between the rollers I to V also used in the Enigma I and the rollers VI to VIII known from the Enigma‑M3 and the two rollers specially designed for the Enigma‑M4, which were thinner than the others and therefore referred to as "thin" rollers.

The technical reason for the production of thin cylinders was the Navy's desire to be able to continue using the same housing as the Enigma I and Enigma‑M3. To do this, the space previously occupied by a (thick) reversing roll now had to be used by a thin reversing roll and one of the newly added thin fourth rolls. Instead of Roman numerals , the thin reels were marked with Greek letters , namely "β" ( Beta ) and "γ" ( Gamma ). Although they could be rotated manually into one of 26 positions, in contrast to reels I to VIII, they did not continue to rotate during the encryption process.

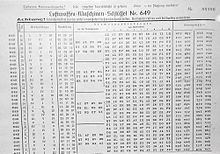

The table shows the top secret wiring diagram of the eight rotating rollers (I to VIII) available on the Enigma-M4, the two non-rotating thin rollers "Beta" and "Gamma" and the two also thin reversing rollers ( VHF) "Bruno" and "Caesar":

| A | B | C | D | E | f | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | u | V | W | X | Y | Z | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | E | K | M | f | L | G | D | Q | V | Z | N | T | O | W | Y | H | X | u | S | P | A | I | B | R | C | J |

| II | A | J | D | K | S | I | R | u | X | B | L | H | W | T | M | C | Q | G | Z | N | P | Y | f | V | O | E |

| III | B | D | f | H | J | L | C | P | R | T | X | V | Z | N | Y | E | I | W | G | A | K | M | u | S | Q | O |

| IV | E | S | O | V | P | Z | J | A | Y | Q | u | I | R | H | X | L | N | f | T | G | K | D | C | M | W | B |

| V | V | Z | B | R | G | I | T | Y | u | P | S | D | N | H | L | X | A | W | M | J | Q | O | f | E | C | K |

| VI | J | P | G | V | O | u | M | f | Y | Q | B | E | N | H | Z | R | D | K | A | S | X | L | I | C | T | W |

| vii | N | Z | J | H | G | R | C | X | M | Y | S | W | B | O | u | f | A | I | V | L | P | E | K | Q | D | T |

| viii | f | K | Q | H | T | L | X | O | C | B | J | S | P | D | Z | R | A | M | E | W | N | I | u | Y | G | V |

| beta | L | E | Y | J | V | C | N | I | X | W | P | B | Q | M | D | R | T | A | K | Z | G | f | u | H | O | S |

| gamma | f | S | O | K | A | N | u | E | R | H | M | B | T | I | Y | C | W | L | Q | P | Z | X | V | G | J | D |

| VHF Bruno | E | N | K | Q | A | u | Y | W | J | I | C | O | P | B | L | M | D | X | Z | V | f | T | H | R | G | S |

| VHF Caesar | R | D | O | B | J | N | T | K | V | E | H | M | L | f | C | W | Z | A | X | G | Y | I | P | S | u | Q |

The wiring of the two thin reels and the reversing reels was thought out in such a way that the combination of the reversing reel (UKW) with the "matching" reel (i.e. Bruno with beta or Caesar with gamma) results in exactly the same involutory character permutation as the reversing reels B and C (thick) the Enigma I and the Enigma‑M3 alone. This served to enable secret communication to other parts of the Wehrmacht that did not have the M4. The only requirement for this was that the U-boats chose the spelling code so that it began with "A". Then the left roller was in exactly the position in which it, together with the appropriate VHF, acted like the corresponding VHF of the other Enigma models.

service

As explained, the Enigma-M4 had eight different reels that were numbered with Roman numerals (I to VIII) and that could be used in any of the three right-hand positions in the reel set. The other two slightly thinner reels only found space on the leftmost position in the reel set. These reels, identified by the Greek letters "Beta" and "Gamma", were succinctly referred to as the "Greek reels" by submarine radio operators. Finally, there were the two reversing rollers, which also differed from the reversing rollers B and C used in the Enigma I by their smaller thickness and were referred to as reversing rollers "B thin" or "Bruno" or "C thin" or "Caesar".

To fully adjust the key, the Navy distinguished between "outer" and "inner" key parts. The inner key included the selection of the reels, the reel position and the ring position. The inner key settings could only be made by an officer, who unlocked the case, selected, set up and arranged the rollers accordingly. Then he closed the Enigma again and handed it over to the radio mate.

The radio operator's task was to make the external key settings, i.e. to insert the ten pairs of plugs into the plug board on the front panel of the M4 according to the key of the day , to close the front flap and then to turn the four rollers into the correct starting position. While the inner settings were only changed every two days, the outer ones had to be changed every day. The key change also happened on the high seas at 12:00 DGZ ("German legal time"), for example in the early morning on submarines that were currently operating off the American east coast.

The keys ordered were listed on “ key boards ”, which were top secret at the time . Here, too, a distinction was made between internal and external attitudes. The key panel intended for the officer with the interior settings looked something like this:

Schlüssel M " T r i t o n "

---------------------------

Monat: J u n i 1945 Prüfnummer: 123

------ ----------------

Geheime Kommandosache!

----------------------

Schlüsseltafel M-Allgemein

---------------------------

(Schl.T. M Allg.)

Innere Einstellung

------------------

Wechsel 1200 Uhr D.G.Z.

--------------------------

----------------------------------------------

|Monats- | |

| tag | Innere Einstellung |

----------------------------------------------

| 29. |B Beta VII IV V |

| | A G N O |

----------------------------------------------

| 27. |B Beta II I VIII |

| | A T Y F |

----------------------------------------------

| 25. |B Beta V VI I |

| | A M Q T |

----------------------------------------------

Only a few days of the month are shown above as an example, with the days being sorted in descending order, as was customary at the time. So you can easily cut off and destroy the "used" codes of the past few days. The other key board was similarly structured, listing the outer key parts.

Schlüssel M " T r i t o n "

---------------------------

Monat: J u n i 1945 Prüfnummer: 123

------ ----------------

Geheime Kommandosache!

----------------------

Schlüsseltafel M-Allgemein

---------------------------

(Schl.T. M Allg.)

Äußere Einstellung

------------------

Wechsel 1200 Uhr D.G.Z.

--------------------------

----------------------------------------------------------------------

| Mo- | | Grund- |

| nats-| S t e c k e r v e r b i n d u n g e n | stel- |

| tag | | lung |

----------------------------------------------------------------------

| 30. |18/26 17/4 21/6 3/16 19/14 22/7 8/1 12/25 5/9 10/15 |H F K D |

| 29. |20/13 2/3 10/4 21/24 12/1 6/5 16/18 15/8 7/11 23/26 |O M S R |

| 28. |9/14 4/5 18/24 3/16 20/26 23/21 12/19 13/2 22/6 1/8 |E Y D X |

| 27. |16/2 25/21 6/20 9/17 22/1 15/4 18/26 8/23 3/14 5/19 |T C X K |

| 26. |20/13 26/11 3/4 7/24 14/9 16/10 8/17 12/5 2/6 15/23 |Y S R B |

Example for the 27th of the month: Inner attitude "B Beta II I VIII" means that the officer had to choose the B (thin) cylinder as the reversing cylinder. The Greek roller Beta was to be used on the left (as a non-rotating roller), then roller II (as a slow rotor) and roller I and finally roller VIII on the right (as a fast rotor). The rings, which are attached to the outside of the roller body and determine the offset between the internal wiring of the rollers and the letter at which the transfer to the next roller takes place, were to be set to the letters A, T, Y and F. (The Greek cylinder was almost always operated with ring position "A".) The officer now handed the M4 over to the radio operator.

The radio operator had to connect the double-pole sockets on the front panel with the corresponding double-pole cables. As a rule, exactly ten cables were plugged in. Six letters remained "unplugged". In the Navy (in contrast to the other Wehrmacht parts), the plug connections were listed numerically and not alphabetically. In the associated secret marine service regulation M.Dv.Nr. 32/1 with the title "The key M - procedure M general" (see also: "The key M" under Weblinks ) a conversion table was given as an aid for the operator.

| A | B | C | D | E | f | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | u | V | W | X | Y | Z |

| 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

Now the encryptor still had to turn the four rollers into a defined starting position and the Enigma‑M4 was ready to encrypt or decrypt radio messages.

key room

The size of the key area of the Enigma‑M4 can be calculated from the four individual partial keys and the number of different possible key settings. The entire key space of the Enigma‑M4 results from the following four factors:

- a) the position of the rollers

- Three out of eight reels for the right three seats are chosen. In addition, one of two Greek rollers for the left seat and one of two reverse rollers on the far left. This results in 2 2 (8 7 6) = 1344 possible roll positions (corresponds to a “ key length ” of around 10 bits ).

- b) the ring position

- There are 26 different ring positions for each of the two reels on the right. The rings of the two left reels do not increase the key space, since the Greek reel is not advanced. A total of 26² = 676 ring positions (corresponds to about 9 bits) are relevant.

- c) the roller position

- There are 26 different reel positions for each of the four reels. (The reversing roller cannot be adjusted.) A total of 26 4 = 456,976 roller positions are available (corresponds to almost 19 bits). If one assumes the ring position to be known, then due to an unimportant anomaly of the stepping mechanism (see also: anomaly ) 26³ = 17,576 initial positions are to be eliminated as cryptographically redundant. 26*26*25*26 = 439,400 roller positions (also corresponds to about 19 bits) then remain relevant.

- d) the plug connections

- A maximum of 13 plug connections can be made between the 26 letters. Assuming the case of the empty patch panel (considered as number zero in the table below), for the first connection there are 26 choices for one connector end and then another 25 for the other end of the cable. There are thus different ways of plugging in the first cable 26*25. But since it doesn't matter in which order the two cable ends are plugged in, half of the options are eliminated. This leaves 26*25/2=325 possibilities for the first connection. For the second one obtains analogously 24*23/2=276 possibilities. In general, there are (26-2 n +2) (26-2 n +1)/2 possibilities for the nth plug connection (see also: Gaussian summation formula ).

connector number |

opportunities for | Possibilities for plug connection |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| first page | second page | ||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 26 | 25 | 325 |

| 2 | 24 | 23 | 276 |

| 3 | 22 | 21 | 231 |

| 4 | 20 | 19 | 190 |

| 5 | 18 | 17 | 153 |

| 6 | 16 | 15 | 120 |

| 7 | 14 | 13 | 91 |

| 8th | 12 | 11 | 66 |

| 9 | 10 | 9 | 45 |

| 10 | 8th | 7 | 28 |

| 11 | 6 | 5 | 15 |

| 12 | 4 | 3 | 6 |

| 13 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

The total number of possible plug combinations when using several plugs results from the product of the possibilities for the individual plug connections. However, since the order of execution does not play a role here either (it is cryptographically equivalent if, for example, A is plugged in first with X and then B with Y or vice versa, first B with Y and then A with X), the corresponding cases must not be used as key combinations are taken into account. With two plug connections, this is exactly half of the cases. The previously determined product must therefore be divided by 2. With three plug connections, there are 6 possible sequences for carrying out the plugging, all six of which are cryptographically equivalent. So the product has to be divided by 6. In the general case, with n plug connections, the product of the previously determined possibilities is divided by n ! ( factorial ) to divide. The number of possibilities for exactly n plug connections is given as

| plug | opportunities for | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| plug connection |

exactly n connectors |

up to n connectors |

|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 325 | 325 | 326 |

| 2 | 276 | 44850 | 45176 |

| 3 | 231 | 3453450 | 3498626 |

| 4 | 190 | 164038875 | 167537501 |

| 5 | 153 | 5019589575 | 5187127076 |

| 6 | 120 | 100391791500 | 105578918576 |

| 7 | 91 | 1305093289500 | 1410672208076 |

| 8th | 66 | 10767019638375 | 12177691846451 |

| 9 | 45 | 53835098191875 | 66012790038326 |

| 10 | 28 | 150738274937250 | 216751064975576 |

| 11 | 15 | 205552193096250 | 422303258071826 |

| 12 | 6 | 102776096548125 | 525079354619951 |

| 13 | 1 | 7905853580625 | 532985208200576 |

With the M4, exactly ten plug connections had to be made. According to the table above, there are 150,738,274,937,250 (more than 150 trillion) plug-in options (corresponds to about 47 bits).

The entire key space of an Enigma‑M4 with three rollers selected from a stock of eight, one of two Greek rollers and one of two reversing rollers and when using ten plugs can be calculated from the product of the 1344 roller layers determined in sections a) to d) above , 676 ring positions, 439,400 roller positions and 150,738,274,937,250 connector options. He is:

- 1344 * 676 * 439,400 * 150,738,274,937,250 = 60,176,864,903,260,346,841,600,000

That's more than 6*10 25 possibilities and corresponds to a key length of almost 86 bits .

The key room is huge. However , as explained in more detail in the main article on the Enigma , the size of the key space is only a necessary but not a sufficient condition for the security of a cryptographic method. Even a method as simple as a simple monoalphabetic substitution (using 26 letters like the M4) has a key space of 26! ( Factorial ), that's roughly 4·10 26 and corresponds to about 88 bits and is therefore even slightly larger than with the Enigma‑M4. Nevertheless, a monoalphabetic substitution is very uncertain and can easily be broken ( deciphered ).

decipherment

Based on the results obtained by Polish codebreakers before the Second World War, British cryptanalysts had been working on deciphering the Enigma since the outbreak of the war in Bletchley Park (BP) , about 70 km north-west of London . The most important tool was a special electromechanical "cracking machine" called the Turing bomb , which had been devised by the English mathematician Alan Turing and with which the valid day key could be determined. "Probable words" were required for this, i.e. text passages that appear in the plain text to be deciphered. The English technical term for it as used in BP is crib . The codebreakers benefited from the German thoroughness in the drafting of routine messages, such as weather reports, with recurring patterns that could be used for deciphering. Soon after the start of the war, the Turing bomb was used to decipher the radio messages encrypted by the Luftwaffe and later also by the army.

The Navy's encryption process, i.e. the "M key", proved to be significantly more resistant to deciphering attempts. Even the Enigma-M3, with its only three (and not yet four) cylinders, was more difficult to break than the Enigma I used by the Luftwaffe and Army. This was entirely due to the use of a larger assortment of cylinders (eight instead of just five to choose from). also essentially in a particularly ingenious procedure for spell key agreement , which the navy used. The British code crackers only succeeded in breaking into the M key in May 1941, after the British destroyer Bulldog (image) had captured the German submarine U 110 along with an intact M3 machine and all secret documents ( code books ) including the important double -letter exchange boards (image) on May 9, 1941. May 1941.

There was a particularly painful interruption ("black-out") for the British when, on February 1, 1942, the M3 (with three rollers) was replaced by the M4 in the submarines. This procedure, called "Triton key network" by the Germans and Shark by the English , could not be broken for ten months, a time that the U‑boat drivers called the " second happy time " in which the German submarine force was once again able to record great successes. The break-in into Shark only succeeded in December 1942, after the British destroyer Petard captured the German submarine U 559 in the Mediterranean on October 30, 1942 . A prize squad boarded the boat and captured important secret key documents such as short signal booklet and weather short key , with the help of which the code breakers in Bletchley Park managed to defeat the Enigma‑M4 and Triton as well. However, it took several days to decipher the messages, which reduced their value.

Now the Americans also came to their aid, who, under the leadership of Joseph Desch in the United States Naval Computing Machine Laboratory (NCML) , based in the National Cash Register Company (NCR) in Dayton ( Ohio ), from April 1943 produced more than 120 high-speed variants produced by the British bomb specifically aimed at the M4. American authorities, such as the Signal Security Agency (SSA) , the Communications Supplementary Activity (CSAW) , and the United States Coast Guard Unit 387 (USCG Unit 387) relieved the British of much of the time-consuming daily "crunchy work" and were able to quickly and easily control the Triton break routinely. The British now left deciphering the M4 to their American allies and their fast Desch bombs . From September 1943, deciphering M4 radio messages usually took less than 24 hours. However, it had to be noted that even if a radio message could be completely deciphered, not all parts were always understandable, because position information was " overcoded " using a special process and was therefore particularly protected. In November 1941, the Navy introduced the so-called address book procedure.

The hijacking of U 505 on June 4, 1944, the only German submarine that was captured by US ships and towed to a port during World War II, was of "inestimable value", and not only because an Enigma was captured , but important key documents such as short signal booklet, identification group booklet and above all the so-called address book . This was the much-needed secret procedure for encrypting U‑boat locations. According to the renowned naval historian Ralph Erskine , the address book was the most important secret document that fell into Allied hands ( English "... making the address book the most valuable item to be taken from U 505" ). The yield of secret material equaled or even exceeded that of U 110 and U 559.

During the entire war, approximately 1,120,000 (more than a million ) naval radio messages were deciphered in Hut Eight (Barrack 8) in BP . This covers the period from autumn 1941 to the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht in May 1945, whereby, with the exception of the "blackout" between February and December 1942, the important continuity (freedom from interruptions) of deciphering could be maintained during the entire time.

War history significance

The deciphering of M4 radio traffic was of enormous importance to Allied advances in anti-submarine warfare . The reports from the boats with precise position and course information provided the Allies with a complete strategic picture of the situation . The submarines gave themselves away by simply sending radio telegrams , which could be detected and localized by Allied warships using radio direction finding such as Huff-Duff . Another important tactical tool for submarine hunting was radar as a means of radio location at sea and ASDIC , an early form of sonar , for sound location under water . But all this did not allow such a complete picture of the situation as "reading" the radio messages provided.

The direct consequence of the American deciphering was the sinking of eleven of the eighteen German supply U‑boats (“milk cows”) within a few months in 1943. This led to a weakening of all Atlantic U‑boats, which are no longer supplied at sea but had to make the long and dangerous journey home through the Bay of Biscay to the submarine bases on the west coast of France.

In particular for the conduct of Operation Overlord , the planned invasion of Normandy, knowledge of a comprehensive, up-to-date and, of course, correct picture of the situation was of crucial importance for the Allied command. After the hijacking of U 505 immediately before the planned " D-Day ", which then took place two days later on June 6, they feared that the key German procedures could suddenly be changed as a result of the news of the hijacking of U 505. This might have prevented the breaking of the Enigma keys on the day of the invasion, with potentially fatal consequences for the invading troops. In fact, however, everything remained unchanged and so the key of the day could be broken in less than two hours after midnight according to the usual pattern using the crib "WEATHER FORECAST BISKAYA " , which the British cryptanalysts could easily guess and correctly guessed, and the invasion was successful.

Many German U‑boat drivers, above all the former chief of the B‑Dienst (observation service) of the Kriegsmarine, were still very sure long after the war that “their” four-barrel key machine was “uncrackable”. When British information became known in the early 1970s that clearly showed that the opposite was the case, it was a real shock to the survivors of the U‑boat war , because of the approximately 40,000 German U‑boat drivers about 30,000 had not returned home from the mission - the highest casualty rate of all German arms. The special wartime significance of the Enigma‑M4 and its deciphering is underscored by a statement by former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill : “The only thing that really frightened me during the war was the U‑boat peril.” I was really afraid of during the war was the submarine threat.")

security check

Due to various suspicious events, several investigations into the safety of their own machine were made on the German side. A significant example of the German considerations, procedures, conclusions and measures derived from them can be found in an English-language, then classified as TOP SECRET "ULTRA" , top -secret interrogation protocol that was released immediately after the war, on June 21, 1945, by the Allied (British- American) TICOM ( Target Intelligence Committee ) in the naval intelligence school in Flensburg-Mürwik . It records the statements of the German naval officer, Lt.zS Hans-Joachim Frowein, who from July to December 1944 was given the task of investigating the safety of the M4 in the OKM/4 Skl II (Detachment II of the Naval War Staff ). The leading German cryptanalyst Wilhelm Tranow , who was also interrogated in this context , explained the reason for this investigation as the extremely high loss rate from which the German submarine weapon had to suffer, particularly in 1943 and in the first half of 1944. The German naval command could not explain this, especially why submarines were sunk in very specific positions, and again asked themselves: "Is the machine safe?"

To clarify this question, Frowein was seconded from Skl III to Skl II for six months from July 1944 with the order to carry out a thorough investigation of the safety of the four-cylinder Enigma. Two more officers and ten men were assigned to him. They began their investigations with the assumption that the enemy knew the machine, including all the reels, and that they had an assumed plain text (crib) of 25 characters in length. The reason for choosing this relatively small crib length was their knowledge that submarine radio messages were often very short. The result of their investigation was: This is sufficient to open up the roller layer and connector.

Frowein was able to explain in detail to the British interrogators his thoughts and procedures for reconnaissance of his own machine. Although neither he nor any of his employees had previously gained experience in cryptanalysing key machines, such as the commercial Enigma , they had succeeded, at least in theory, in breaking the M4 within half a year. The methods developed bore a striking resemblance to the procedures actually used by the British in BP , which of course Frowein did not know. As he went on to explain, he had also recognized that his break-in method would be severely disrupted if the left or middle reel within the crib were to advance . Then case distinctions would have become necessary in the cryptanalysis, which would have increased the workload by a factor of 26, which was considered to be practically unacceptably high for a possible attacker.

After presenting the results, the Skl came to the conclusion that although the M3 and even the M4 could theoretically be attacked, this was no longer the case if care was taken to ensure that the roller advancement (the middle roller) happened sufficiently often. In December 1944 it was therefore ordered that from now on only cylinders with two transfer notches , i.e. one of cylinders VI, VII or VIII, could be used as the right-hand cylinder. This measure halved the number of possible roll positions (from 8*7*6=336 to 8*7*3=168), which meant a weakening of the combinatorial complexity , but at the same time the machine was strengthened against the identified weakness.

As his British interrogation officers already knew at the time, Frowein's investigation results and conclusions were absolutely correct and the Skl's derived measures for the cryptographic strengthening of the M4 were fundamentally correct. Nevertheless, the Germans underestimated the fact that the Allies had already fully penetrated the Enigma. For example, if at least five notches had been used instead of just two (as in the British Typex ) to make reel advancement much more frequent, and if all eight reels (instead of just three) had been so equipped, it probably would have helped. However, even such measures could not have prevented a burglary with certainty. It would have been much better if the rollers could be wired freely, similar to the Dora reversing roller occasionally used by the Luftwaffe from 1944 , and to limit the number of rollers in the Enigma not to just three or four, but, similarly to on the Enigma II (from 1929) to use eight reels side by side in the machine. The decisive cryptographic element of the key, for which there is no cryptanalytic abbreviation, namely the number of roller layers, would then have 8 interchangeable rollers! or 40,320 instead of the actually realized comparatively tiny 336 or only 168.

Above all, however, any strengthening implemented in December 1944 came at least five years too late to jeopardize or even prevent the Allied successes achieved up to that point. The Navy also sent the test results to the other parts of the Wehrmacht, which continued to use only the Enigma I, which was cryptographically weaker than the M4 and had only three cylinders and the resulting 60 cylinder layers. According to Frowein's statement in the TICOM report, the army command was "astonished at the Navy's view based on this investigation" (...the Army were astonished at the Navy's view based on this investigation) .

chronology

Some important points in the history of the Enigma‑M4 are listed below:

| 23 Feb 1918 | First patent for the Enigma |

| 26 Jul 1939 | Two-day secret Allied meeting at Pyry (handover of reels I to V) |

| 12 Feb 1940 | Capture of reels VI and VII from U 33 |

| Aug 1940 | Capture of reel VIII |

| May 1941 | Bletchley Park receives a copy of the Weather Shortcut Key captured by U 110 |

| 5 Oct 1941 | Introduction of the "Triton" key net for the submarines, initially with the M3 |

| 15 Oct 1941 | Introduction of the key network "Neptune" for the battleships already with the M4 |

| 1 Feb 1942 | Introduction of the M4 now also for the submarines (initially only Greek roller β ) |

| 30 Oct 1942 | HMS Petard captures second issue of U 559 's weather short key |

| 12 Dec 1942 | BP manages to break into Triton |

| March 10, 1943 | Third Edition of the Weather Shortcut Key |

| July 1, 1943 | Introduction of the Greek roller γ |

| year | J | f | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1939 | O | O | O | O | ||||||||

| 1940 | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 1941 | O | O | O | O | # | # | # | # | # | O | # | # |

| 1942 | # | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | # |

| 1943 | # | # | O | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| 1944 | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| 1945 | # | # | # | # | # |

Legend:

- o No deciphering possible

- # Deciphering succeeds

The three gaps (o) in the deciphering ability of the Allies are striking. The reasons for this are: In October 1941 " Triton " was formed as a separate key network only for the submarines (initially with the M3). In February 1942, the M4 was introduced, which could only be overcome ten months later in December. In March 1943 there was a new edition of the weather short key . From September 1943, the M4 radio messages were usually broken within 24 hours.

Authentic radio message

A message from Kapitänleutnant Hartwig Looks , commander of the German submarine U 264 , which was encrypted on November 19, 1942 with an Enigma‑M4, serves as an example. Before encryption, the radio operator converted the text into a short version, which he then encrypted letter by letter with the M4 and finally sent the ciphertext in Morse code. Since the Enigma can only encrypt capital letters, numbers were written out digit by digit, punctuation marks were replaced by "Y" for comma and "X" for period, proper names enclosed in "J" and important terms or letters were doubled or tripled to protect against misunderstandings caused by transmission errors. Also, it was common for the Navy to arrange the text in groups of four, while the Army and Air Force used groups of five. Short radio messages and the writing and transmission errors that are almost unavoidable in practice make deciphering based on statistical analyzes more difficult.

Detailed plain text :

- From U 264 Hartwig Looks - radio telegram 1132/19 - content:

- During a depth charge attack , we were pushed under water . The last enemy location we recorded was at 8:30 a.m. Marine Square AJ 9863, course 220 degrees, speed 8 nautical miles per hour . We follow up. Weather data: Air pressure falling by 1014 millibars . Wind from the north-northeast, force 4. Visibility 10 nautical miles .

Abbreviated plaintext:

- From Looks - FT 1132/19 - Contents:

- Pushed underwater when attacked, Wabos.

- Last opponent at 0830

- Mar.-Qu. AJ 9863, 220 degrees, 8 nm. push after

- 14mb, falls. NNE 4th view 10th

Transcribed plaintext in groups of four:

vonv onjl ooks jfff ttte inse insd reiz woyy eins neun inha ltxx beia ngri ffun terw asse rged ruec ktyw abos xlet zter gegn erst andn ulac htdr einu luhr marq uant onjo tane unac htse chsd reiy zwoz wonu lgra dyac htsm ysto ssen achx eins vier mbfa ellt ynnn nnno oovi erys icht eins null

Ciphertext (with spelling and transcription errors):

NCZW VUSX PNYM INHZ XMQX SFWX WLKJ AHSH NMCO CCAK UQPM KCSM HKSE INJU SBLK IOSX CKUB HMLL XCSJ USRR DVKO HULX WCCB GVLI YXEO AHXR HKKF VDRE WEZL XOBA FGYU JQUK GRTV UKAM EURB VEKS UHHV OYHA BCJW MAKL FKLM YFVN RIZR VVRT KOFD ANJM OLBG FFLE OPRG TFLV RHOW OPBE KVWM UQFM PWPA RMFH AGKX IIBG

The ciphertext could be deciphered on February 2, 2006 with the following key settings (see also "Modern decipherment of the M4" under Weblinks ):

Key:

- VHF: Bruno, reel position: Beta 2 4 1

- Ring position: AAAV

- Connector: AT BL DF GJ HM NW OP QY RZ VX

- Spell key: VJNA

Deciphered text (with spelling and transcription errors):

"von von j looks j hff ttt one one three two yy qnns nine content xx pressed when attacking under water y wabos x last standing nul eight three nul o'clock mar qu anton iota nine eight seyhs three y two two nul grad y eight sm y pushes after x ekns four mb falls y nnn nnn ooo four y sight one zero"

literature

- Arthur O. Bauer : Direction finding as an Allied weapon against German U‑boats 1939–1945 . Self-published, Diemen Netherlands 1997, ISBN 3-00-002142-6 .

- Friedrich L. Bauer : Secrets deciphered. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin et al. 2000, ISBN 3-540-67931-6 .

- Ralph Erskine , Frode Weierud : Naval Enigma - M4 and its Rotors. In: Cryptology . Vol. 11, No. 4, 1987, pp. 235-244, doi:10.1080/0161-118791862063 .

- Stephen Harper: Battle for Enigma. The Hunt for U‑559 . Mediator, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-8132-0737-4 .

- OKM : The key M – Procedure M General . Berlin 1940. cryptomuseum.com (PDF; 3.3 MB)

- Joachim Schröder: Momentous find - the "case" U 110 and the sensational capture of the "Enigma" . In: Clausewitz - The Magazine for Military History , Issue 1, 2015, pp. 56-61.

- Hugh Sebag-Montefiore : Enigma – The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, ISBN 0-304-36662-5 .

web links

details

- Enigma M4 at the Crypto Museum .

- Key M4 photo gallery and explanations of the M4 and accessories (English).

- The History of Hut Eight 1939-1945 by A.P. Mahon.

- The different types of submarine radio messages (PDF, 378 kB), excerpts from the book by Arthur O. Bauer.

- The pinch from U 559 , capture of the weather short key and the short signal booklet (English).

Documents

- The Key M (PDF; 3.3 MB), scan of the original 1940 regulation in the Crypto Museum .

- Double-letter exchange panels Password: "Source".

- Double letter exchange boards Password: "Sea".

- Double letter swap board B Password: "Fluss" (authentic spelling).

decipherments

- Breaking German Navy Ciphers , modern decipherment of the M4.

- M4 Message Breaking Project , modern decipherment of the M4 (English).

- Allied Breaking of Naval Enigma by Ralph Erskine.

exhibits

Photos, videos and audios

- Photo of a "Greek roller" Beta (β) in the Crypto Museum.

- Video interview with Hartwig Looks (2003) on a convoy attack on YouTube (4′15″).

replica projects

- Replica of an M4 .

- Replica of an M4 (English).

Simulations of the M4

- Windows , Enigma I, M3 and M4 realistically visualized (English).

- MAC OS (English).

- RISC OS (English).

itemizations

- ↑ Friedrich L. Bauer: Secrets deciphered. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin et al. 2000, p. 115.

- ↑ The key M - procedure M general . Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine, Berlin 1940, p. 26. cdvandt.org (PDF; 0.7 MB) accessed on December 29, 2020.

- ↑ Enigma M4 and Neptune at the Crypto Museum . Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ↑ Scan of a (then) secret letter from the OKM dated October 15, 1941 to the commander of the battleships with receipt stamp of October 23, 1941, retrieved from the Crypto Museum on December 21, 2020.

- ↑ Ralph Erskine, Frode Weierud: Naval Enigma - M4 and its Rotors. Cryptologia, 11:4, 1987, p. 237, doi:10.1080/0161-118791862063 .

- ↑ Friedrich L. Bauer: Secrets deciphered. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin et al. 2000, p. 119.

- ↑ The key M - procedure M general . Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine, Berlin 1940, p. 23. cdvandt.org (PDF; 0.7 MB) accessed April 15, 2008

- ↑ Arthur O. Bauer: Radio direction finding as an Allied weapon against German U‑boats 1939–1945 . Self-published, Diemen Netherlands 1997, pp. 31–48, ISBN 3-00-002142-6 .

- ↑ Dirk Rijmenants: Enigma Message Procedures Used by the Heer, Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine. Cryptologia, 2010, 34:4, pp. 329-339, doi:10.1080/01611194.2010.486257 .

- ↑ Authentic key panel key M Triton . PDF; 0.5 MB Retrieved April 4, 2021 at Frode Weierud's CryptoCellar .

- ↑ The key M - procedure M general . Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine, Berlin 1940, p. 26. cdvandt.org (PDF; 0.7 MB) retrieved: April 15, 2008

- ↑ Louis Kruh: How to use the German Enigma Cipher Machine - A Photographic Essay. Cryptologia, 1983, 7:4, pp. 291-296, doi:10.1080/0161-118391858026 .

- ↑ Arthur O. Bauer: Radio direction finding as an Allied weapon against German U‑boats 1939–1945 . Self-published, Diemen Netherlands 1997, ISBN 3-00-002142-6 , p. 33.

- ↑ Ralph Erskine , Frode Weierud : Naval Enigma - M4 and its Rotors. Cryptologia, 1987, 11:4, pp. 235-244, doi:10.1080/0161-118791862063 .

- ↑ John AN Lee, Colin Burke , Deborah Anderson: The US Bombes, NCR, Joseph Desch, and 600 WAVES - The first Reunion of the US Naval Computing Machine Laboratory . IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, 2000. p. 35. thecorememory.com (PDF; 0.5 MB) accessed 23 May 2018.

- ↑ Impact Of Bombe On The War Effort , accessed May 23, 2018.

- ↑ Gordon Welchman: The Hut Six Story - Breaking the Enigma Codes . Allen Lane, London 1982; Cleobury Mortimer M&M, Baldwin Shropshire 2000, p. 11. ISBN 0-947712-34-8

- ↑ Gordon Welchman: The Hut Six Story - Breaking the Enigma Codes . Allen Lane, London 1982; Cleobury Mortimer M&M, Baldwin Shropshire 2000, ISBN 0-947712-34-8 , p. 230.

- ↑ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, ISBN 0-304-36662-5 , pp. 149 ff.

- ↑ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, ISBN 0-304-36662-5 , p. 225.

- ↑ Rudolf Kippenhahn: Encrypted messages, secret writing, Enigma and chip card . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60807-3 , p. 247.

- ↑ Stephen Harper: Battle for Enigma - The Hunt for U‑559 . Mittler, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-8132-0737-4 , p. 50 ff.

- ↑ Stephen Harper: Battle for Enigma - The Hunt for U‑559 . Mittler, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-8132-0737-4 , p. 66 ff.

- ↑ Naval Enigma at macs.hw.ac.uk (English), accessed 30 December 2020.

- ↑ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, ISBN 0-304-36662-5 , p. 311.

- ↑ Jennifer Wilcox: Solving the Enigma - History of the Cryptanalytic Bombe . Center for Cryptologic History , NSA, Fort Meade 2001, p52. nsa.gov ( Memento of 19 July 2004 at the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 0.6 MB) retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ↑ Naval Enigma at macs.hw.ac.uk (English), accessed 30 December 2020.

- ^ Already on August 28, 1941, the British had captured U 570 , towed it to Iceland and commissioned the Royal Navy on September 19, 1941 as HMS Graph .

- ↑ Clay Blair: Submarine Warfare Vol. 2, p. 795.

- ↑ Ralph Erskine, Captured Kriegsmarine Enigma Documents at Bletchley Park , Cryptologia, 2008, 32:3, pp. 199-219, doi:10.1080/01611190802088318 .

- ↑ Ralph Erskine: The German Naval Grid in World War II. Cryptologia, 1992, 16:1, p. 47, doi:10.1080/0161-119291866757 .

- ↑ Clay Blair: Submarine Warfare Vol. 2, p. 798.

- ↑ The History of Hut Eight 1939 – 1945 by A.P. Mahon, p. 115. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ↑ Erich Gröner: The German warships 1815-1945; - Volume 3: U‑boats, auxiliary cruisers, mine ships, net layers, barrier breakers . Bernard & Graefe, Koblenz 1985, ISBN 3-7637-4802-4 , pp. 118f

-

↑ After Eberhard Rössler: History of German submarine construction. Volume 1. Bernard & Graefe, Bonn 1996, ISBN 3-86047-153-8 , pp. 248-251 the following boats of type XB (4 of 8) and type XIV (7 of 10) were lost from May to October 1943 :

- on May 15; however, according to Wikipedia on May 16, U 463 (type XIV),

- on June 12 U 118 (Type XB),

- on June 24 U 119 (Type XB),

- on July 13, U 487 (Type XIV),

- on July 24 U 459 (Type XIV),

- on July 30 U 461 (Type XIV),

- on July 30 U 462 (Type XIV),

- on Aug. 4 U 489 (Type XIV),

- on Aug. 07 U 117 (type XB),

- on Oct. 4 U 460 (Type XIV),

- on Oct. 28 U 220 (Type XB).

- ↑ Francis Harry Hinsley, Alan Stripp: Codebreakers - The inside story of Bletchley Park . Oxford University Press, Reading, Berkshire 1993, ISBN 0-19-280132-5 , p. 121.

- ↑ Friedrich L. Bauer: Secrets deciphered. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin et al. 2000, p. 221.

- ↑ Winston Churchill: The Second World War. 1948 to 1954, six volumes. (German: The Second World War. Scherz-Verlag, Bern/Munich/Vienna 1985, ISBN 3-502-16131-3 ), awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

- ↑ TICOM I-38: Report on Interrogation of Lt. Frowein of OKM/4 SKL III, on his work on the security on the German Naval Four-Wheel Enigma. Naval News School, Flensburg-Mürwik, June 1945. (English).

- ↑ Philip Marks : Reversing Roller D: Enigma's rewirable reflector – Part 1 . In: Cryptologia , 25:2, 2001, pp. 101-141.

- ↑ Philip Marks: Reversing Roller D: Enigma's rewirable reflector – Part 2 . In: Cryptologia , 25:3, 2001, pp. 177-212.

- ↑ Philip Marks: Reversing Roller D: Enigma's rewirable reflector – Part 3 . In: Cryptologia , 25:4, 2001, pp. 296-310.

- ↑ Louis Kruh, Cipher Deavours: The commercial Enigma – Beginnings of machine cryptography . Cryptologia, 26:1, pp. 1-16, doi:10.1080/0161-110291890731 .

- ↑ TICOM I-38: Report on Interrogation of Lt. Frowein of OKM/4 SKL III, on his work on the security on the German Naval Four-Wheel Enigma. Naval News School, Flensburg-Mürwik, June 1945, p. 5. (English).

- ↑ Ralph Erskine: The Poles Reveal their Secrets - Alastair Dennistons's Account of the July 1939 Meeting at Pyry . cryptology. Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 30.2006,4, p. 294

- ↑ David Kahn: An Enigma Chronology . cryptology. Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 17.1993.3, pp. 240, ISSN 0161-1194 .

- ↑ David Kahn: An Enigma Chronology . cryptology. Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 17.1993.3, pp. 239, ISSN 0161-1194 .

- ↑ Friedrich L. Bauer: Secrets deciphered. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin et al. 2000, p. 220.

- ↑ Allied breaking of Naval Enigma Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ↑ Looks Message , accessed December 28, 2020.

- ↑ Authentic radio message from U 264 and its deciphering , retrieved December 28, 2020.