Reversing roller D

In the reverse roller D , also reversing roll Dora (abbreviation: FM D ), by the British onomatopoeic Uncle Dick ( German "Uncle Dick " called), is a special reversing roller in the roller set of Enigma , so the rotor cipher machine , with the the German military encrypted their radio messages during World War II . The VHF D is characterized by the fact that its wiring - in contrast to all other Enigma rollers - could be changed by the user depending on the key.

The reversing roller D was used by the German Air Force for the Enigma I from January 1, 1944 . Similar to the reversing rollers A, B and C known from the Army Enigma (see also: Enigma rollers ), it causes the letters to be interchanged after the flow from the entry roller has passed through the three rotating rollers of the roller set and guides the Current back through the roller set before it leaves it again through the entry roller. A major cryptographic weakness of all Enigma rollers, especially their reversing rollers (A, B and C), was that their wiring was fixed and could not be changed by the user. This weakness was overcome by the introduction of the UKW D and could have led to a significant strengthening of the cryptographic security of the Enigma if this cylinder had been used suddenly and across the board, which could no longer be realized due to the war.

function

As early as 1883, the Dutch cryptologist Auguste Kerckhoffs formulated his binding maxim for serious cryptography under the assumption that Shannon later (1946) explicitly stated "the enemy knows the system being used" (German: "The enemy knows the system being used").

- Kerckhoffs' principle : The security of a cryptosystem must not depend on the secrecy of the algorithm . Security is only based on keeping the key secret.

The cryptographic security of the Enigma depended - contrary to Kerckhoffs' maxim - essentially on the secrecy of its roller wiring. This could not be changed by the user, so it was part of the algorithm and not of the key. It is noteworthy that the reel wiring was never changed from its beginnings in the 1920s until 1945. Under the usual conditions of use of a key machine as widespread as the Enigma, one cannot assume that its algorithmic components can be kept secret in the long term, even if the Germans tried.

A first possibility to improve the Enigma would have been the annual complete replacement of the range of rollers (each with radically changed wiring), similar to what the Swiss did with their K model. Rollers whose internal wiring could be designed variably depending on the key would be even more effective. Interestingly, there was an approach to this, namely the reverse roller D (British nickname: "Uncle Dick"), which had exactly this property, but was only used late (Jan. 1944) and only occasionally. This "reversing roller Dora" (photo see Pröse p. 40), as it was called by the German side using the spelling alphabet used at the time, enabled freely selectable wiring between the contact pins and thus a variable connection between pairs of letters. For example, the letter A, which on the "old" VHF A, B and C was rigidly wired with the letters E, Y or F (see also: table in the chapter Structure of the Enigma overview article ), could be assigned to one (almost ) any letters can be repositioned. This also applies to the other letters, which could now be paired as desired, although there was a small exception due to the design. Due to the idiosyncratic labeling and the need to fix the cover cap, the letters J and Y, which were firmly connected as a pair of letters on the VHF D and therefore did not appear as plug contacts to the outside. (This is symbolized by dashes in the table below. For the British cryptanalysts in Bletchley Park (BP), who chose an opposing and offset counting method for the VHF contacts, this corresponded to the letters B and O).

UKW D A B C D E F G H I K L M - N O P Q R S T U V W X Z - B.P. A Z Y X W V U T S O R Q P N M L K J I H G F E D B C

The remaining 24 freely insertable letters expanded the key space of the Enigma when using the VHF D by a factor of 316.234.143.225 (more than 300 billion or a good 38 bits), as can be seen from the formula mentioned in the chapter key space (in the Enigma overview article) ( using 24! instead of 26! and n = 12) can easily be recalculated. The VHF D was therefore cryptographically much more effective than the rigidly wired VHF A, B and C, admittedly without avoiding the fundamental weakness of all VHF, namely involutorism . Nevertheless, due to the significant increase in the combinatorial complexity of the Enigma machine, it could have caused quite a headache on the Allied side if it had been introduced suddenly and across the board. This is confirmed by a quote from an American investigation report written shortly after the war:

“How close the Anglo-Americans came to losing out in their solution of the German Army Enigma is a matter to give cryptanalysts pause. British and American cryptanalysts recall with a shudder how drastic an increase in difficulty resulted from the introduction by the German Air Force of the pluggable reflector ('Umkehrwalze D', called 'Uncle Dick' by the British) in the Spring of 1945. It made Completely obsolete the 'bomb' machinery which had been designed and installed at so great an expense for standard, plugboard-Enigma solution. It necessitated the development by the US Navy of a new, more complex machine called the 'duenna,' and by the US Army of a radically new electrical solver called the 'autoscritcher.' Each of these had to make millions of tests to establish simultaneously the unknown (end-plate) plugboard and the unknown reflector plugging. Only a trickle of solutions would have resulted if the pluggable reflector had been adopted universally; and this trickle of solutions would not have contained enough intelligence to furnish the data for cribs needed in subsequent solutions. Thus even the trickle would have eventually vanished. "

“How close the Anglo-Americans were about to lose the ability to decipher the German Army Enigma is a matter that makes cryptanalysts breathless. British and American code breakers remember with a shudder what a drastically increased complication from the introduction of the plug-in reversing roller ('reversing roller D', called 'Uncle Dick' by the British) by the German Air Force in the spring of 1945 [actually: in the spring of 1944] resulted. This made the ' bomb fleet ' completely useless, which had been designed and built with so much effort to solve the normal plug board Enigma. Inevitably, the US Navy had to develop a new, much more complicated machine called the ' Duenna ', and the US Army had to develop a completely new electrical solution machine called the ' Autoscritcher '. Each of these machines had to carry out millions of tests in order to simultaneously fathom the unknown (front panel) connector board and the unknown wiring of the reversing roller [D]. There would only have been a trickle of solutions if the plug-in reversing roller had been used in general; and these droplets of solution would not have contained sufficient information to provide indications for cribs needed for further solutions. In the end, even the trickling would have dried up. "

In fact, the reversing roller D was not introduced suddenly and across the board, but, presumably due to production bottlenecks caused by the war and also, as has since been done by the German cryptologist Dr. Erich Hüttenhain known, because of its arduous and error-prone handling only occasionally and in a few key circles, for example by the Air Force in Norway, while mostly the well-known VHF B was still used - a fatal cryptographic error.

Even before the VHF D was used for the first time, the code breakers learned of its planned introduction on January 1, 1944, because five days before the turn of the year they intercepted a radio message in which a German radio operator asked his colleague unencrypted whether he was already doing it I have a new reversing roller Dora. The Germans made another mistake when on the first day of the new year one side was still using VHF B, while the remote station in Norway had already used VHF D. Since both radio operators used otherwise identical roller positions, ring positions and plug connections in accordance with the valid daily key , the British had already found out the current wiring from Uncle Dick on January 2nd . In the weeks and months that followed, the British stayed on the Germans' track and followed the wiring changes of the VHF D, which were made three to four times a month at intervals of about seven to twelve days. A key board of the Luftwaffe captured in July 1944 during " Operation Overlord " in Normandy with details of the VHF D (see also: Luftwaffe machine key under Web links ) was particularly helpful , which confirmed the British assumptions about the function and use of this VHF .

See also

- Enigma (review article)

- Enigma-G

- Enigma-M4

- Enigma watch

- Enigma rollers

- Enigma equation

literature

- Friedrich L. Bauer : Deciphered Secrets. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin a. a. 2000, ISBN 3-540-67931-6 .

- Philip Marks : Reversing roller D: Enigma's rewirable reflector - Part 1 . In: Cryptologia , 25: 2, 2001, pp. 101-141.

- Philip Marks: Reversing roller D: Enigma's rewirable reflector - Part 2 . In: Cryptologia , 25: 3, 2001, pp. 177-212.

- Philip Marks: Reversing roller D: Enigma's rewirable reflector - Part 3 . In: Cryptologia , 25: 4, 2001, pp. 296-310.

- Olaf Ostwald and Frode Weierud : History and Modern Cryptanalysis of Enigma's Pluggable Reflector. Cryptologia, 40: 1, 2016, pp. 70–91, doi: 10.1080 / 01611194.2015.1028682 cryptocellar.org (PDF; 4 MB)

- Michael Pröse: Encryption machines and deciphering devices in World War II - history of technology and aspects of IT history . Dissertation at Chemnitz University of Technology, Leipzig 2004. tu-chemnitz.de (PDF; 7.9 MB)

- Heinz Ulbricht: The Enigma cipher machine - deceptive security . A contribution to the history of the intelligence services. Dissertation Braunschweig 2005. tu-bs.de (PDF; 4.7 MB)

Web links

- Crypto Museum photos and detailed information on UKW D

- Photo of an Enigma machine on VHF D

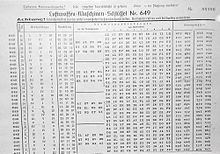

- Air Force machine key no. 619 (PDF; 309 kB) Authentic key board with information on the wiring of the VHF D

Individual evidence

- ^ Claude Shannon: Communication Theory of Secrecy Systems . In: Bell System Technical Journal , Vol 28, October 1949, p. 662, netlab.cs.ucla.edu (PDF; 0.6 MB), accessed March 26, 2008

- ↑ Auguste Kerckhoffs: La cryptographie militaire . In: Journal des sciences militaires , Volume 9, pp. 5–38 (Jan. 1883) and pp. 161–191 (Feb. 1883), petitcolas.net (PDF; 0.5 MB) accessed March 26, 2008

- ↑ David H. Hamer, Geoff Sullivan, Frode Weierud: Enigma Variations - An Extended Family of Machines . In: Cryptologia . Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 22.1998,1 (July), p. 11, ISSN 0161-1194 , cryptocellar.org (PDF; 0.1 MB) accessed November 11, 2016

- ↑ CHO'D. Alexander: Method for testing "Holmes Hypothesis" for UD Bletchley Park 1998, p. 14, cryptocellar.org (PDF; 0.1 MB) accessed November 11, 2016

- ↑ Friedrich L. Bauer : Deciphered secrets. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin a. a. 2000, p. 115.

- ↑ Michael Pröse: Encryption machines and deciphering devices in the Second World War - the history of technology and aspects of the history of IT . Dissertation Technische Universität Chemnitz, Leipzig 2004, p. 40, tu-chemnitz.de ( Memento of the original from September 4, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 7.9 MB) accessed March 26, 2008

- ↑ Heinz Ulbricht: The Enigma encryption machine - Deceptive security . A contribution to the history of the intelligence services. Dissertation Braunschweig 2005, p. 10, tu-bs.de (PDF; 4.7 MB) accessed March 26, 2008

- ^ Gordon Welchman: The Hut Six Story - Breaking the Enigma Codes . Allen Lane, London 1982; Cleobury Mortimer M&M, Baldwin Shropshire 2000, p. 11. ISBN 0-947712-34-8

- ↑ a b The US 6812 Bomb Report 1944 . 6812th Signal Security Detachment, APO 413, US Army. Tony Sale, Bletchley Park, 2002. p. 39, codesandciphers.org.uk (PDF; 1.3 MB) accessed March 16, 2010.

- ^ Army Security Agency: Notes on German High Level Cryptography and Cryptanalysis . European Axis Signal Intelligence in World War II, Vol 2, Washington (DC), 1946 (May), p. 13, nsa.gov ( Memento of the original from June 11, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 7.5 MB) accessed January 16, 2012.

- ^ Army Security Agency: Notes on German High Level Cryptography and Cryptanalysis . European Axis Signal Intelligence in World War II, Vol 2, Washington (DC), 1946 (May), p. 13, nsa.gov ( Memento of the original from June 11, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 7.5 MB) accessed November 22, 2010.

- ↑ Friedrich L. Bauer: Deciphered secrets. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin a. a. 2000, p. 118.