Enigma key procedure

The key procedures (also called: encryption regulations, encryption rules or key instructions) for the Enigma key machine were guidelines drawn up by the German armed forces for the correct use of the machine. They served, the sender and authorized receiver of a secret - message to enable to set their machines key identical to each other. Just so the recipient could one by the sender encrypted radio message that his Enigma decrypt and the original plain text read.

principle

It is fundamentally important not to encrypt all messages (radio messages) in a key network with identical keys . This would be a fundamental error , in cryptology as " plain text plaintext compromise " ( English Depth ) announced the unauthorized deciphering So, the " break would greatly facilitate" of Proverbs. In this regard, the cryptographically most secure solution would be to use completely different, i.e. individual, keys, similar to a one-time password . However, this would have the serious disadvantage that the key generation as well as the administration, distribution and use of such “one-time keys” would be extremely time-consuming and actually “not suitable for the field”.

The Wehrmacht therefore looked for a compromise between keys that were as uniform as possible and therefore easily distributable (within a key network) and a procedure to design them in a certain way "individual" so that they were - at least partially - different. The basic problem arises of how to communicate the individual information required to decrypt a radio message to the authorized recipient without it being compromised and then used to break the message unauthorized.

Regulations

The various parts of the Wehrmacht ( army , air force and navy ) developed different key procedures for this. The elaborated encryption rules have been modified several times and in some cases considerably. The respectively valid key procedure was described in detail as operating instructions for the user, known as the “ keyer ”, in the service regulations that were secret at the time. Examples are the secret army service regulation H.Dv.g. 14 with the title "Key Instructions for the Enigma Key Machine" and the Marine Service Regulations M.Dv.Nr. 32/1 “The key M - Procedure M general” (Fig . ) .

Daily key

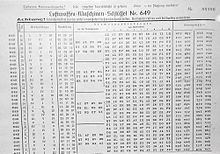

A distinction was made between two partial keys for setting the machine keys. Part of the key remained constant for a certain period of time (usually one or two days) and was the same for all machines in a key network (see for example: Triton key network ). This partial key was called the “ day key ” and also referred to as the “basic key ” or “basic setting”. In the navy, the basic setting was further subdivided into the "inner settings" (also: "inner key") and the "outer settings" (also: "outer key"). For more information, see key procedure in the Kriegsmarine (further down in the article). The daily key could be distributed in advance, mostly for one to three months, to all participants in a key network, which was done with the help of top secret (“ Secret commando! ”) Key boards (picture) .

Spell key

The other part of the key was chosen individually for each individual radio message and consequently referred to as the “message key ”. In contrast to the daily key, which was the same for all participants and was known from the key board, the (individual) message key was transmitted to the authorized recipient together with each individual radio message using a suitable method. This had to be done in such a way that no unauthorized person could infer the key from the information transmitted for this purpose. The procedure used for this was referred to as “spell key encryption”. This procedure in particular changed from time to time and was solved completely differently in the navy than in the two other parts of the armed forces (army and air force).

Army and Air Force

As described in the main article on the Enigma under Operation , the day key of the Enigma I consisted of four components , namely

- Roll position, for example B123,

- Ring position, for example 16 26 08,

- Plug connections, for example AD CN ET FL GI JV,

- and roller position, for example RDK.

Until 1938

In the early years of the Enigma, around 1930, well before the Second World War , until September 14, 1938, all four of the above components of the key were specified. The user had to set up the Enigma accordingly, whereby the roller position prescribed in the key board was interpreted as the "basic position". The key operator now had to think of a three-letter "key phrase" that was as arbitrary as possible, for example WIK. He now had to encrypt this with the previously set Enigma and the basic setting (here RDK) (picture) . In order to prevent conceivable transmission errors during the subsequent radio transmission , it was mandatory to encrypt the message key (here WIK) not just once, but twice in a row. This is called the " key duplication ".

The encryptor enters WIKWIK via the Enigma's keyboard and observes which lamps light up. In this example it is KEBNBH. This is the "encrypted saying key".

In saying head (preamble) of the to-ending radio message these six letters are as important information the actual ciphertext prefixed. They are used by the recipient to determine the spell key (here WIK). In order to determine this after receiving the message, the recipient, who also knows the daily key and has thus set his Enigma to be identical to that of the sender, enters the encrypted message key received from him (here KEBNBH) and in turn observes which lamps light up. Due to the involvement of the Enigma (encrypt = decrypt) it receives the six letters WIKWIK. From the repetition of the letter pattern , he recognizes that the transmission was error-free and that he received the spell key unmutilated . He can now set the Enigma's rollers to the correct starting position WIK and thus decode the ciphertext. As a result, he receives the original plain text.

From 1938 to 1940

The method described above is anything but cryptographically secure. On the contrary, the duplication of the slogan key represents a cardinal error which the German cipher unit responsible for it made . Although those responsible had no idea what gross mistake had happened to them and what fatal consequences this had already had for them (see cyclometer ), certain weaknesses of the procedure were probably recognized and therefore changed in September 1938.

From September 15, 1938, a new regulation on key encryption came into force. The basic position, which is uniformly prescribed as part of the daily key, has been abolished. From now on, the daily key consisted of only three components, namely

- Roll position, for example B123,

- Ring position, for example 16 26 08,

- and plug connections, for example AD CN ET FL GI JV.

The key operator's new task was to come up with an arbitrary basic position made up of three letters (for example, here again RDK for easier illustration). Then - as before - he had to create an arbitrary spell key, again from three letters, and - also as before - to encrypt it twice in a row with the Enigma set to the basic key. The headline originally consisting of six letters has been expanded to nine letters, in the example RDK KEBNBH.

An important cryptographic improvement through this new procedure was that in this way the basic settings for a day within a key network were no longer identical, but became individual and different. Although this strengthened the method, it still did not make it safe enough (see Bomba ), which the Wehrmacht High Command (OKW) had no idea.

From 1940

On May 1, 1940 (nine days before the start of the western campaign ) the key procedure was radically changed again in the army and air force. The (cryptographically fatal) key duplication had turned out to be operationally unnecessary, since radio transmission disruptions occurred far less frequently than feared. The duplication of spell keys has been abolished. The daily key still consisted of only three components, as before

- Roll position, for example B123,

- Ring position, for example 16 26 08,

- and plug connections, for example AD CN ET FL GI JV.

As before, the operator has to come up with an arbitrary basic position (here for the sake of simplicity again RDK) and any desired key (here for example again WIK). He sets the Enigma to the basic key (here RDK) and encrypts the saying key (here WIK), but now only once . As a result, he receives the encrypted spell key consisting of only three letters, here KEB. He communicates this to the recipient together with the basic position he has chosen as part of the message head, i.e. here RDK KEB.

The recipient interprets this information as follows: Set the Enigma (already preset according to the daily key) to the basic position (here RDK) and then enter the three letters (here KEB). He then sees three lamps light up one after the other (here WIK). This is the correct slogan key needed to decrypt the message. He adjusts his Enigma accordingly, can now decrypt the ciphertext and receives the plaintext.

From 1944

While the procedure described above was essentially retained in most units of the army and air force until the end of the war , some units of the air force, for example in Norway , started using the reversing roller D (UKW D) from January 1, 1944 . It was a major cryptographic innovation. This special VHF was distinguished - in contrast to all other Enigma rollers - in that its wiring could be changed "in the field" by the user depending on the key. The key regulation and also the key and the key table (picture above) have been expanded accordingly .

From July 10, 1944, the Luftwaffe introduced another cryptographic complication in the form of the " Enigma clock " for some units . It was an additional device that was connected to the plug board of the Enigma and, selectable via a rotary switch, caused forty (00 to 39) mostly non-invulatory letters to be swapped. (In contrast to this, the swaps caused by the Enigma plug board are always involutorial.) The respective position of the rotary switch was communicated to the authorized recipient of the encrypted radio message separately from the daily key. This was done in the first few weeks of using the clock by specifying the number expressed in words that described the position of the rotary switch, i.e. an entry between ZERO (00) and DREINEUN (39). From November 2, 1944, the position of the rotary switch was coded in the form of four letters. Two alphabets were used here, which were indicated on a plaque (picture) inside the case cover (see also Use of the Enigma watch ).

Navy

In contrast to the Enigma I used by the Army and Air Force, the Enigma-M3 (picture) used by the Navy had a range of eight (and not just five) rollers, three of which had to be selected and inserted into the machine according to the daily key . The inner key was the selection of the rollers, the roller position and the ring position. The internal key settings were only allowed to be made by an officer who unlocked the Enigma housing, selected, set up and arranged the rollers accordingly. Then he closed the Enigma again and handed it over to the radio mate. Its task was to make the external key settings, i.e. to insert the ten pairs of plugs according to the daily key into the connector board on the front panel of the machine, to close the front flap and then to turn the rollers to the correct starting position.

While the internal settings were only changed every two days, the external ones had to be changed every day. The key change also happened on the high seas at 12:00 DGZ (“German legal time”), for example in the early morning for submarines that were currently operating off the American east coast.

One of the main strengths of the key procedure used by the Kriegsmarine was based on the ingenious procedure for the key agreement agreement , which was cryptographically much more "watertight" than the (above) comparatively simple and faulty methods of the other Wehrmacht parts. Characteristic for the procedure of the Kriegsmarine were a separate identification group book ( code book ) as well as various double-letter exchange tables that were used to " encode " the slogan key (see also: The identification group book of the Kriegsmarine ).

U-boats until 1942

Until 1942, the submarines used the same machine (M3) and also the same procedures as the other units of the Navy that had a machine key, even if the submarines already had separate key networks at that time, for example "Native waters" (later called: "Hydra") decreed. (Smaller naval units, such as harbor ships that did not have a machine key , used simpler manual key procedures such as the shipyard key .) On October 5, 1941, the Triton key network was introduced as a new, separate key network exclusively for the Atlantic submarines. Here, too, the M3 and the usual procedures were initially used.

Submarines from 1942

This changed abruptly on February 1, 1942, when the M3 (with three rollers) in the Triton key network was replaced by the new Enigma-M4 (photo) with four rollers. In addition to the eight available rollers of the M3, three of which were used, there was a new roller for the M4, which was always on the far left of the roller set, and enlarged it from three to four rollers. The new roller was designed to be narrower than the others for reasons of space and was marked with the Greek letter “β” ( beta ). The submariners called it the "Greek roller". Although this roller could be turned manually to one of 26 rotational positions, in contrast to rollers I to VIII, it did not continue to rotate during the encryption process. Nevertheless, this measure has significantly improved the cryptographic security of the Enigma.

On July 1, 1943, the Navy introduced an alternative Greek cylinder "γ" ( Gamma ), which could be used instead of the "β". The changes called had the consequence that at the submarine-key panels to the existing parameters, also, that in addition the "thin" to be selected Greeks roller and to be inserted FM "Bruno" (B) or "Caesar" (C) to perform was.

literature

- Friedrich L. Bauer : Deciphered Secrets. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin a. a. 2000, ISBN 3-540-67931-6 .

- Marian Rejewski : An Application of the Theory of Permutations in Breaking the Enigma Cipher . Applicationes Mathematicae, 16 (4), 1980, pp. 543-559. PDF; 1.6 MB. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- Marian Rejewski: How Polish Mathematicians Deciphered the Enigma . Annals of the History of Computing, 3 (3), July 1981, pp. 213-234.

- Dirk Rijmenants: Enigma Message Procedures Used by the Heer, Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine . Cryptologia , 34: 4, 2010, pp. 329-339.

Web links

- Enigma Message Procedures at Dirk Rijmenants (English) with authentic German keyboards, accessed on December 6, 2018.

- OKM: The key M. Scan of the original regulation from 1940 PDF; 3.3 MB. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- OKW : Key instructions for the Enigma key machine . H.Dv. G. 14, Reichsdruckerei , Berlin 1940. (Copy of the original manual with a few small typing errors.) Accessed December 6, 2018. PDF; 0.1 MB ( memento from September 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dirk Rijmenants: Enigma Message Procedures Used by the Heer, Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine . Cryptologia , 34: 4, 2010, p. 329 ff.

- ↑ OKW : Key instructions for the Enigma key machine . H.Dv. G. 14, Reichsdruckerei , Berlin 1940, p. 7. (Copy of the original manual with a few small typing errors.) Accessed December 6, 2018. PDF; 0.1 MB ( memento from September 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ OKW : Key instructions for the Enigma key machine . H.Dv. G. 14, Reichsdruckerei , Berlin 1940. (Copy of the original manual with a few small typing errors.) Accessed December 6, 2018. PDF; 0.1 MB ( memento from September 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ The key M - Procedure M General. OKM , M.Dv.Nr. 32/1, Berlin 1940, p. 13. PDF; 3.2 MB

- ^ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, p. 355. ISBN 0-304-36662-5 .

- ↑ Dirk Rijmenants: Enigma Message Procedures Used by the Heer, Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine . Cryptologia, 34: 4, 2010, p. 331.

- ^ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, p. 355. ISBN 0-304-36662-5 .

- ↑ Friedrich L. Bauer: Deciphered secrets. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin a. a. 2000, pp. 411-417.

- ^ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, p. 357. ISBN 0-304-36662-5 .

- ^ Friedrich L. Bauer: Decrypted Secrets, Methods and Maxims of Cryptology . Springer, Berlin 2007 (4th edition), p. 123, ISBN 3-540-24502-2 .

- ↑ Friedrich L. Bauer: Deciphered secrets. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin a. a. 2000, pp. 417-420.

- ↑ Philip Marks : Umkehrwalze D: Enigma's rewirable reflector - Part 1 . Cryptologia , Volume XXV, Number 2, April 2001, p. 107.

- ↑ Michael Pröse: Encryption machines and deciphering devices in the Second World War - the history of technology and aspects of the history of IT . Dissertation at Chemnitz University of Technology, Leipzig 2004, p. 40.

- ^ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, p. 214. ISBN 0-304-36662-5 .

- ↑ Ralph Erskine and Frode Weierud: Naval Enigma - M4 and its Rotors. Cryptologia, 11: 4, 1987, p. 236

- ^ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, ISBN 0-304-36662-5 , p. 225.

- ↑ Friedrich L. Bauer: Deciphered secrets. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin et al. 2000, p. 220.