Bomba

The Bomba (plural: Bomby , Polish for “bomb”), more precisely Bomba kryptologiczna (Polish for “cryptological bomb”), was an electromechanically operated cryptanalytic machine, which was devised in 1938 by the Polish mathematician and cryptanalyst Marian Rejewski around the to decipher encrypted communications of the German military with the rotor key machine Enigma . The prerequisite for their functioning was the German procedural error of the duplication of the slogan key , which the Polish code breakers were able to exploit with their Bomby to unlock the roll position and the slogan key of the Enigma.

background

After the invention of the Enigma by Arthur Scherbius in 1918, the Reichswehr of the Weimar Republic began using this innovative type of machine encryption on an experimental basis from the mid-1920s , and then increasingly regularly from 1930. Germany's neighbors, above all France, Great Britain and Poland, followed this with suspicion, especially when the National Socialist rule began in 1933 and this key machine established itself as a standard procedure in the course of the armament of the Wehrmacht . While it failed French and the British, in the encryption break and they classified the Enigma as "unbreakable," the 27-year-old Polish mathematicians succeeded Marian Rejewski in his work in the charge of Germany Unit BS4 of Biuro Szyfrów (German: "Cipher Bureau" ), the first break-in in 1932 (see also: Deciphering the Enigma ). To do this, he and his colleagues Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski exploited a serious procedural error that the Germans had made.

Saying key duplication

In order to be able to communicate secretly with the help of the Enigma key machine, four partial keys , namely the roller position, the ring position , the connector and the roller position on the transmitter and receiver had to be set identically (see also: Operation of the Enigma ). For this purpose (at that time) highly secret keyboards with information that changed daily, called “ daily keys ” , were used by both communication partners. In order to ensure that not all radio messages of a key network are encrypted with identical keys, which would make the texts vulnerable, it was prescribed to set an individual starting position of the three reels for each message, which was referred to as the " saying key ".

The cryptographic problem that was seen by the German side was to give the authorized recipient of the message the message key without exposing it to an unauthorized decipherer. For this reason, the spell key was transmitted in encrypted form (spell key encryption). From the beginning of the 1930s until September 1938, the procedural regulation was to set up the Enigma according to the daily key, i.e. in particular to turn the three rollers by hand to the basic position specified there. The encryptor then had to choose any roller start position as arbitrarily as possible for each of the three rollers, for example "WIK". To ensure that the recipient received the message key without errors despite possible signal mutilation, the message key was placed twice in a row to be on the safe side, ie doubled in the example for "WIKWIK". This duplicated spell key obtained in this way was then encrypted. To do this, the six letters had to be entered one after the other using the Enigma's keyboard and the lights that lit up had to be read, for example "BPLBKM". This was the duplicated and encrypted spell key.

Instead of first doubling the slogan key and then encrypting it, the German cryptographers in the cipher station of the Reichswehr Ministry could have considered simply sending the encrypted slogan key two times in direct succession, i.e. "BPLBPL", or at a distance (for example once at the beginning "BPL" and then again at the end of the radio message "BPL"). The redundancy required for the desired error detection could also have been achieved in this way. However, this would have had the obvious disadvantage that the attention of an unauthorized attacker would have been drawn to this point by the conspicuous repetition and he would have concentrated his attack on it. In order to prevent this, and in the futile effort to achieve perfect security, the supposedly good idea was to first double the spell key and then encrypt it, since at first glance no repetition could be seen. In reality, however, this method chosen represented a serious cryptographic error.

It was flawed to stipulate that the operator himself could “choose as desired” a key. People, especially in stressful situations, tend to find simple solutions. (This is still true today, as you can see from the sometimes carelessly chosen passwords .) Instead of the "random" key required by the regulation, it was not uncommon for very simple patterns such as "AAA", "ABC" or " ASD ”(adjacent letters on the keyboard) were used, which the code breakers could easily guess. It was also disadvantageous to encrypt the slogan key with the Enigma yourself, because this exposed the selected setting of the machine. If, on the other hand, an independent procedure had been used, similar, for example, to the double-letter exchange tables used by the Navy , then a cryptanalysis of the spell key would not have allowed any conclusions to be drawn about the Enigma. A simple repetition of the motto key, as the Navy did during World War II, would have been the cryptographically more secure variant. As it turned out, the duplication of the key was not necessary, on the contrary, firstly, it was superfluous and, secondly, it was more of a hindrance than useful for operational purposes. Because when the doubling of the army and air force was finally abolished in 1940 , operations continued without any problems. In fact, the Germans didn't have to encrypt the spell key at all. It could have simply been transmitted as plain text. It would have made no difference whether it had been transferred simply, doubled or even tripled. (In the latter case, not only an error detection, but even an error correction would have been made possible.) Because of the unknown ring position, the knowledge of the roll start position alone is of no use to the attacker. Instead, the flawed method of duplicating the slogan key created the serious cryptographic weakness of the Enigma, which in the 1930s proved to be a decisive Achilles' heel , and which made it possible for the Polish cryptanalysts in the Biuro Szyfrów to break in and allow them to access the chosen slogan key.

Cyclometer as a forerunner

→ Main article: cyclometer

In addition to duplicating the slogan key, the Germans made another serious cryptographic error in the early 1930s. A basic position was specified in the keyboards for the encryption of the key, which was to be used uniformly by all encryptors as the initial position of the cylinder for encrypting the (freely chosen) key. This meant that the Poles had dozens, if not hundreds, of Enigma radio messages every day, all of which had been encrypted with the same basic position of the machine. All the motto keys of one day were encrypted with completely identical keys and thus cryptanalytically vulnerable. Taking advantage of both procedural errors made by the Germans (uniform basic position and duplication of slogans), the Polish cryptanalysts constructed a special cryptanalytic device, called a cyclometer , which embodied two Enigma machines connected in series and offset by three rotary positions.

With the help of the cyclometer, the code breakers were able to determine for each of the six possible roller positions which characteristic permutations occurred in the respective possible 26³ = 17,576 different roller positions. The cyclometer helped to systematically record the very laborious and time-consuming work of recording the specific properties of the letter permutation caused by the Enigma roller set for all 6 · 17,576 = 105,456 possible cases. The characteristics determined in this way were then sorted and collected in a catalog. The work on this catalog was completed by the Poles in 1937. They had thus created ideal conditions for deciphering the German Enigma radio messages. The creation of this catalog of characteristics , Rejewski said, "was laborious and took more than a year, but after it was finished [...] day keys could [be] determined within about 15 minutes".

After the Germans replaced the Enigma's reverse cylinder (VHF) on November 1, 1937 - the VHF A was replaced by the new VHF B - the Polish code breakers were forced to start the laborious catalog creation from scratch a second time. Even before they could finish this work, the Germans changed their process engineering on September 15, 1938. The uniform basic position was abolished and a new indicator procedure was introduced instead, with the basic position for the key encryption now also being "arbitrary". Suddenly this made the catalog of characteristics and the cyclometer useless and the Biuro Szyfrów was forced to come up with new methods of attack. This led to the invention of the punch card method by Henryk Zygalski and to the construction of the bomba by Marian Rejewski.

Name origin

The origin of the name Bomba (German: "Bombe") is not clear. After the war, even Marian Rejewski could not remember how this name came about. The anecdote handed down by Tadeusz Lisicki is gladly told, according to which Rejewski and his colleagues Różycki and Zygalski had just eaten an ice bomb in a café while he was formulating the idea for the machine. Then Jerzy Różycki suggested this name. Another hypothesis is that the machine dropped a weight, similar to the way an airplane drops a bomb, and so clearly audibly signaled that a possible roller position had been found. A third variant assumes the operating noise of the machine, which is said to have resembled the ticking of a time bomb, as the reason for the name. The appearance of the machine, which is said to have resembled the typical hemispherical shape of an ice bomb, is also given as the origin of the name. Unfortunately, no bombs have survived, making it difficult to verify the various hypotheses of the name. Rejewski himself stated quite soberly that the name came about because they “couldn't think of anything better” (English: “For lack of a better name we called them bombs.” ).

functionality

With the change in the German procedural regulations and the introduction of the freely selectable basic position for the spell key encryption on September 15, 1938, as explained, the cyclometer and the catalog of characteristics suddenly became useless. Thanks to the remaining weakness of the spell key doubling, however, which the Polish cryptanalysts were able to continue to exploit, it took only a few weeks in the autumn of 1938 until Rejewski found and was able to implement a suitable method to break the spell key again.

The idea behind the bomba is based solely on the procedural weakness of the key doubling described. The Poles knew neither the roller position nor the ring position nor the connector used by the Germans. In addition, the basic position was no longer chosen uniformly, but set individually and arbitrarily by each encryptor. Nevertheless, it was still clear that the spell key was first doubled and then encrypted. From this, the Polish cryptanalysts were able to further deduce that the first and fourth, second and fifth as well as the third and sixth ciphertext letters of the encrypted proverb key were each assigned to the same plain text letter. This important finding enabled them to search for a pattern using the letter pattern “123123”.

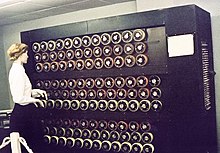

The technical implementation of this cryptanalytical attack method consisted in the construction of an electromechanically operated machine, which contained six complete Enigma roller sets and thus embodied two Enigma machines connected three times in a row and each offset by three rotary positions. The Poles succeeded not only in developing the concept of the bomba and constructing the machine very quickly , but also in October 1938 , with the help of the telecommunications company AVA ( AVA Wytwórnia Radiotechniczna ), located at Warsaw's 25 Stepinska Street, to manufacture and successfully operate machines . Since there were (at that time) six different possible roller layers of the Enigma, six bombies were built, one for each roller layer. Driven by an electric motor, a bomba exhaustively (completely) ran through all 17,576 different roller positions (from “AAA” to “ZZZ”) within a time of about 110 minutes.

The cryptanalytic attack consisted of finding positions in which, when a certain check letter was entered, an arbitrary initial letter resulted, which was repeated identically when the roller position was rotated three further. This identity check did not have to be carried out one after the other, but could be carried out simultaneously, as each Bomba had six complete Enigma roller sets (each correctly wired rollers I, II and III in different positions plus the reversing roller B, but without ring positions and without a connector board ) decreed. These were interconnected to form three pairs of rollers, each pair being responsible for a different one of the three letters of the secret key. Positions were sought in which all three pairs of rollers simultaneously signaled identity.

This coincidence happened very rarely and was therefore a strong characteristic for a hit , that is, the correctly determined roller position and roller position of the Enigma. But you also had to reckon with false hits, i.e. positions in which three pairs of identical initial letters "happened" without the correct key being found. On average, there was around one miss per roll layer. The Polish cryptanalysts use specially reproduced Enigma machines to detect missed hits and find the correct key. These were set accordingly using the key candidates for roller position and basic position determined by the bomby .

Finally, the intercepted ciphertext was entered on a trial basis. If German-language clear text fragments then appeared, which the Polish cryptanalysts, who spoke fluent German, could easily recognize, then it was clearly a real hit and the correct roller position, roller position, ring position and at least some of the connectors had been found. Finally, it was comparatively easy for the code breakers to open up the remaining correct connector pairs and, if necessary, to fine-tune the rings. This revealed the complete key, determined the plain text and completed the deciphering.

example

The concrete execution of the cryptanalytic attack method implemented by the bomba can be illustrated using an example. The key procedure is the procedure as it was used in the period from September 15, 1938 (freely selectable basic position for the slogan key encryption and use of five to eight plugs) and before January 1, 1939 (conversion to up to ten plugs) . For example, the roller position “B123”, ring position “abc” and a plug board with five plugs “DE”, “FG”, “HI”, “JK” and “LM” are assumed to be the secret daily key , which the Polish cryptanalysts did not know, of course . The encryptor arbitrarily selected any basic position, for example "BVH", as well as the secret saying key, for example "WIK". As explained, the saying key was doubled and encrypted with the Enigma set to the day key and the selected basic position. As a result (which can be reproduced with the help of freely available simulation programs, see also: Web links in the Enigma overview article ) he receives the encrypted slogan key, which he puts in front of the actual ciphertext together with the unencrypted basic position as an indicator: "BVH BPLBKM".

For the cryptanalysts it was first necessary to intercept and collect as many Enigma radio messages as possible one day and to view the indicators used in each case. The aim was to find three encrypted spell keys, in which the first and fourth, then the second and fifth and finally the third and sixth letters were identical. In the above example, this is already the case for the first and fourth letters of the encrypted key phrase “BPLBKM”, both of which are “B” here. Now two more matching indicators had to be found in which the second and fifth letters or the third and sixth letters were also a "B".

In principle, it would also have been possible to check for three different fixed points instead of three identical fixed points (as one can denote the letters that appear in pairs in the duplicated and encrypted spell key, here "B"). This would have simplified the search for three suitable indicators, since indicators with any identical letter pairs occur more frequently and are easier to find than a trio with three identical letter pairs. However, due to the plug board, which swapped letter pairs before and after passing through the set of rollers in a way unknown to the Poles, it was necessary, with luck, to catch a letter (here "B") that was not plugged in (English: self-plugged ). If you caught a plugged in , deciphering failed. If only five to eight plugs were used, as was still common in 1938, the probability of this was around 50%. If, on the other hand, one had checked for three different fixed points instead of three identical ones, the probability of catching an unplaced letter three times would have fallen to around 12.5%. The efficiency of the procedure would have suffered accordingly. For this reason, the Polish cryptanalysts opted for the more difficult to find but much more effective combination of three identical fixed points.

A drawing of the bomba can be found in the publication "Secret Operation Wicher", which is listed under web links . In the right part of the picture a mounted roller set (1) and five still empty spindles for the other roller sets can be seen above, as well as the electric motor (2) below, which drives all six roller sets synchronously via the central gear. In addition to the power switch on the front, three alphabet columns (3) can be seen in the left part. This indicates that it was also possible to enter three different check letters.

Assuming that after viewing many German officials, in addition to the indicator “BVH BPLBKM” (from above), “DCM WBVHBM” and “EJX NVBUUB” were found. This gives a desired set of three suitable indicators:

1) BVH BPLBKM 2) DCM WBVHBM 3) EJX NVBUUB

For a further understanding, the concept of the difference between roller positions (also: distance between roller positions) is important. It is known that there are 26³ = 17,576 different roller positions per roller layer. Starting for example with “AAA” and the number 1, “AAB” as number 2 and so on up to “ZZZ” with the number 17,576, these could be numbered consecutively. It is not known whether and which numbering was used by the Poles for the 17,576 cylinder positions. In any case, the British Codebreakers used the following convention at their headquarters, Bletchley Park (BP), about 70 km north-west of London : Starting with “ZZZ” and the number 0, they counted “ZZA” as number 1, “ZZB” as number 2 and so on until the end “YYY” as number 17,575. This way of counting, which at first glance is a bit confusing, has the practical advantage that it is particularly easy to calculate differences between two roller positions, similar to the more common calculation in the widespread hexadecimal system , with the difference that here, not base 16, but base 26 was used. The letter “Z” in the British 26 system corresponds to the number “0” in the hexadecimal system and the highest number (“F” in the hexadecimal system with the decimal value 15) was the “Y” with the decimal value 25 in the British 26 system "YYY" symbolizes the numerical value 25 · 26² + 25 · 26 + 25 = 17,575 in the 26 system. The associated differences (distances) for the basic positions specified above are therefore "AGE" as the difference between the first basic position "BVH" and the second basic position "DCM" and "AGK" as the distance from the second basic position "DCM" to the third basic position "EJX" .

To break the key, the Polish cryptanalysts set their six bombies as follows: Each one was set up on a different one of the six possible roller positions, one of them consequently on the correct roller position "B123". The roller sets of each bomba were set to different basic positions according to the differences found above. The six individual roller sets of a bomba each formed three pairs. Within each pair, the distance between the roller positions was exactly three, the distance between the pairs corresponded to the differences determined above. Then the electric motor was switched on and the six roller sets ran through all 17,576 possible positions within two hours at constant intervals, synchronized via a gearbox, at a frequency of almost three positions per second.

The aim was to find those positions in which each of the three pairs of rollers on the bomba produced an identical initial letter at the same time. This coincidence event was technically determined using a simple relay circuit. In the above example and the roller position B123, this is the case with the test letter "B" for only two positions. The first of these is a miss. The second results in the position "BUF" for the first roller set and correspondingly offset positions for the other five roller sets, from which the three basic positions "BUF", "DBK" and "EIV" (normalized to the ring positions "aaa") result as Derive solution candidates.

The Polish code breakers received the basic positions openly communicated in the respective headline, ie, “BVH”, “DCM” and “EJX” through a simple comparison, i.e. difference formation, of the three normalized basic positions “BUF”, “DBK” and “EIV” found in this way directly to the secret ring positions of the German daily key. In all three cases, the difference is “abc”.

After unmasking the roller position and ring positions, a replica Enigma (with an empty connector board) could be set accordingly (roller position "B123", ring positions "abc" and basic positions "BVH", "DCM" or "EJX") and after entering the encrypted one on a trial basis Spell Keys lit the following lamps:

1) BVH BPLBKM → WHHWSF 2) DCM WBVHBM → HPDIPZ 3) EJX NVBUUB → EHAEHA

The expected pattern “123123” of the doubled spell key already appears in the third case, even if not yet (as it turns out later) with consistently correct letters. (While “E” and “A” are already correct, the “H” is still wrong.) In the first two cases, only one pair of letters is identical (marked green and underlined above). The reason for the discrepancies observed is the completely unplugged (empty) plug board. The last task that the Poles around Marian Rejewski had to solve was to find the five to eight plugs that the Germans had used. There was no set procedure for this. Rather, they had to use the “ trial and error ” method to plug individual “promising” plug candidates into a replicated Enigma and then work through subsequent sample decryption to obtain the “123123” pattern for all three keys at the same time. It made sense to do this work in parallel with three Enigma replicas that were set to the three different basic positions ("BVH", "DCM" or "EJX"), i.e. to try the same candidate connector on all three machines at the same time.

Intuition, experience, accuracy and perseverance were required for this work, qualities that the Polish experts undoubtedly possessed. A good way of proceeding is often to try to plug in a pair of letters that are not yet identical, such as "H" and "I" in the second case. If you do this, the slogan key candidate improves from "HPDIPZ" to "IPDIPZ". An identical pair became two. This is a strong indication of a correctly found connector. Another promising attempt is to insert the corresponding ciphertext letters instead of the plaintext letters that are not yet identical. As is known, the plug board is run through twice, once on the plain text page and once on the ciphertext page. For example, in the first case, the third (“H”) and sixth letters (“F”) of the key candidate “WHHWSF” are not identical. The trial plug "FH" brings no improvement here. Alternatively, you can also put the corresponding third (“L”) and the sixth ciphertext letter (“M”) of the present encrypted slogan key together and you will immediately be rewarded with the result “WHJWSJ”. Again, an identical pair of letters turned into two identical pairs of letters, and another correct plug was found. If you add this newly found connector "LM" for the second case, for which "HI" has already been unmasked, the key candidate from "IPDIPZ" improves further in "IPDIPD", which thus already shows the expected pattern "123123". Conversely, if you add “HI” in the first case, you get “BPLBKM → WIJWSJ” as an interim solution. If you still find “JK” as a plug, which can be guessed from the letters appearing here, then the expected pattern and the cracked saying “WIKWIK” also result for the first case.

If you bring this arduous work to the end and discover the two remaining plugs “DE” and “FG”, whereby sample decryption of the intercepted ciphertext using the determined phrase key “WIK” is helpful, then all three phrase keys are clearly available and with the Now fully cracked day key, all German radio messages of the day, as well as by the authorized recipient, could ultimately be easily decrypted and read.

End of the bomba

The six bombs helped the Poles in autumn 1938 to maintain the continuity of deciphering ability, which was important for the continued cryptanalysis of the Enigma, which threatened to be lost after the introduction of the freely selectable basic position for the spell key encryption on September 15, 1938. On December 15, 1938, however, came the next severe blow. The Germans put two new rollers (IV and V) into operation. This increased the number of possible roller layers from six (= 3 · 2 · 1) to sixty (= 5 · 4 · 3). Instead of 6 · 17,576 = 105,456 possible positions there were suddenly ten times as many, namely 60 · 17,576 = 1,054,560 (more than a million) cases to be examined. Suddenly 60 bombs were required, which exceeded the Polish production capacities.

Only two weeks later, at the turn of the year 1938/39, there was another, even more serious, complication. This not only caused quantitative problems for the Poles, it also posed considerable qualitative difficulties. Instead of plugging in between five and eight connecting cables (ie swapping “only” 10 to 16 letters using the plug board), seven to ten plugs were used from January 1, 1939 (corresponds to 14 to 20 permuted letters). Suddenly only six to a maximum of twelve of the 26 letters of the Enigma were unplugged. Taking into account the fact that the plug board is run through twice during encryption (see also: Structure of the Enigma ), the probability of catching an unplugged letter (twice) dropped dramatically. Correspondingly, the effectiveness of the Polish machine decreased considerably. From the beginning of 1939, the existing bombs could hardly help to determine the German keys. Ultimately, with the dropping of the spell key duplication on May 1, 1940, the Polish concept of the bomba became completely useless.

At this point in time, however , the bomby no longer existed, because in September 1939, after the German attack on their country , the Polish cryptanalysts had to flee Warsaw and destroyed the cryptanalytical machines they had carried while they were fleeing from the advancing armed forces and shortly afterwards , on September 17th, the Red Army crossing the Polish eastern border .

Turing bomb as successor

For the British Codebreakers , the wide range of assistance and the boost they received from their Polish allies were undoubtedly extremely valuable, possibly even decisive, in order to “get off the starting blocks” in the first place. The secret Pyry meeting of French, British and Polish code breakers held on July 26th and 27th, 1939 in the Kabaty Forest of Pyry about 20 km south of Warsaw was almost legendary . In doing so, the Poles confronted their British and French allies with the astonishing fact that for more than six years they had succeeded in what the Allies had tried in vain to do and which they now considered impossible, namely to crack the Enigma. The Poles not only gave the astonished British and French the construction drawings of the bomba and revealed their methodologies, but also made all their knowledge of the functionality, weaknesses and cryptanalysis of the German machine, as well as its successes in deciphering, available. In addition, they also handed over two copies of their Enigma replicas. In particular, the knowledge of the wiring of the Enigma rollers and the functionality and structure of the Bomba was extremely important and helpful for the British. The English mathematician and cryptanalyst Gordon Welchman , who was one of the leading minds of the British code breakers in Bletchley Park, expressly praised the Polish contributions and assistance by writing: “... had they not done so, British breaking of the Enigma might well have failed to get off the ground. " (German:" ... had they [the Poles] not acted like this, the British break of the Enigma might not have gotten off the starting blocks at all. ")

Shortly after the Pyry meeting, also in 1939, and undoubtedly inspired by the extremely valuable Polish information, the English mathematician and cryptanalyst Alan Turing invented the Turing bomb named after him . Shortly afterwards, this was improved significantly by his compatriot and colleague Welchman through the invention of the diagonal board (German: "Diagonal board "). Both the Polish word "bomba" and the French word "bombe" used by the British mean the same thing in English, namely "bomb" (German: "bomb"). However, it would be wrong to conclude from the similarity of names of the two cryptanalytic machines and the close technical and chronological connection that the Turing bomb was little more than a slightly modified British replica of the Polish bomba . On the contrary, the cryptanalytic concept of the British bomb differs significantly from that of the Bomba and goes far beyond that. Apart from the name and the same target as well as the technical commonality of using several Enigma roller sets within the machine and running them through all 17,576 possible roller positions, there are hardly any similarities between the Polish and the British machine.

The decisive disadvantages of the Bomba , which Turing deliberately avoided during its development, were its dependence on the German procedural error of the duplication of the slogan key and on as many unplugged letters as possible. After the Germans fixed these errors, the bomba was useless. The British bomb, on the other hand, did not depend on the duplication of the spell key and could therefore continue to be used without restriction until the end of the war, even after Turing had foreseen the dropping of the spell key duplication. In addition, a decisive advantage of the British concept and another important difference to the Polish approach was the ability of the bomb to completely effect the plug board by linking several (usually twelve) Enigma roller sets in a ring and with the help of cribs ( probable words assumed in the text ) to be able to shed. In contrast to the bomba , which became less and less effective as the number of plugs increased, the British bomb would still have been able to identify keys if the Germans - which they erroneously did not do - had inserted all 26 letters (with the help of 13 double connector cords) and not a single letter would have been left unplugged.

Both machines, bomba and bomb , were and are not in competition with each other. Each of them represents the outstanding intellectual achievements of their creators, who thus created the prerequisites for achieving the war-essential deciphering of the German Enigma machine. Without these, the Second World War would have taken a different course and the world would look different today.

chronology

Some important points in the history of the bomba are listed below:

| Jun 1, 1930 | Commissioning of the Enigma I (six plugs and quarterly changing roller positions) | |

| 1934 | Development and completion of the cyclometer | |

| Jan. 1, 1936 | Monthly change of the roller position | |

| Oct. 1, 1936 | Daily change of the roller position and instead of six now five to eight plugs | |

| Nov 2, 1937 | Replacement of VHF A by VHF B | |

| Sep 15 1938 | New indicator procedure (freely selectable basic position for the key encryption) | |

| Sep./Oct. 1938 | Design and manufacture of six bombies | |

| Dec 15, 1938 | Commissioning of rolls IV and V | |

| Jan. 1, 1939 | Seven to ten plugs | |

| Jul 26, 1939 | Two days allied meeting at Pyry | |

| Aug 19, 1939 | Ten plugs | |

| 8 Sep 1939 | Dissolution of Biuro Szyfrów in Warsaw and destruction of the Bomby while fleeing to Romania | |

| May 1, 1940 | Dropping the spell key duplication |

See also

- Enigma (review article)

- Enigma-G

- Enigma-M4

- Enigma watch

- Enigma rollers

- Enigma patents

- Enigma equation

- Polish Enigma replica

- Turing bomb

- Cyclometer (cryptology)

literature

- Friedrich L. Bauer : Deciphered Secrets. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin et al. 2000, ISBN 3-540-67931-6 .

- Chris Christensen: Review of IEEE Milestone Award to the Polish Cipher Bureau for `` The First Breaking of Enigma Code '' . Cryptologia . Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 39.2015,2, pp. 178-193. ISSN 0161-1194 .

- Rudolf Kippenhahn : Encrypted messages, secret writing, Enigma and chip card . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60807-3

- Władysław Kozaczuk : Enigma - How the German Machine Cipher Was Broken, and How It Was Read by the Allies in World War Two . Frederick, MD, University Publications of America, 1984, ISBN 0-89093-547-5

- Władysław Kozaczuk: Secret Operation Wicher . Bernard et al. Graefe, Koblenz 1989, Karl Müller, Erlangen 1999, ISBN 3-7637-5868-2 , ISBN 3-86070-803-1

- David Link: Resurrecting Bomba Kryptologiczna - Archeology of Algorithmic Artefacts, I. , Cryptologia , 33: 2, 2009, pp. 166-182. doi : 10.1080 / 01611190802562809

- Tadeusz Lisicki : The performance of the Polish deciphering service in solving the method of the German "Enigma" radio key machine in J. Rohwer and E. Jäkel: The radio clearing up and its role in the Second World War , Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart, 1979, pp. 66-81 . PDF; 1.7 MB . Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- Hugh Sebag-Montefiore : Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, ISBN 0-304-36662-5

- Gordon Welchman : From Polish Bomba to British Bombe: The Birth of Ultra . Intelligence and National Security, 1986.

- Gordon Welchman: The Hut Six Story - Breaking the Enigma Codes . Allen Lane, London 1982; Cleobury Mortimer M&M, Baldwin Shropshire 2000, ISBN 0-947712-34-8

Web links

- Artist's impression of the Bomba. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- Secret operation Wicher of the Polish secret service

Individual evidence

- ↑ Simon Singh: Secret Messages . Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2000, p. 199. ISBN 3-446-19873-3

- ^ Marian Rejewski: An Application of the Theory of Permutations in Breaking the Enigma Cipher . Applicationes Mathematicae, 16 (4), 1980, pp. 543-559. Accessed: January 7, 2014. PDF; 1.6 MB

- ↑ Friedrich L. Bauer: Deciphered secrets. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin a. a. 2000, p. 412.

- ↑ Friedrich L. Bauer: Deciphered secrets. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin et al. 2000, p. 412.

- ^ Kris Gaj, Arkadiusz Orłowski: Facts and myths of Enigma: breaking stereotypes. Eurocrypt, 2003, p. 4.

- ^ A b c Gordon Welchman: The Hut Six Story - Breaking the Enigma Codes . Allen Lane, London 1982; Cleobury Mortimer M&M, Baldwin Shropshire 2000, p. 213. ISBN 0-947712-34-8

- ^ Rudolf Kippenhahn: Encrypted messages, secret writing, Enigma and chip card . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, p. 226. ISBN 3-499-60807-3

- ^ Gordon Welchman: The Hut Six Story - Breaking the Enigma Codes . Allen Lane, London 1982; Cleobury Mortimer M&M, Baldwin Shropshire 2000, p. 207. ISBN 0-947712-34-8

- ^ A b c Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, p. 355. ISBN 0-304-36662-5

- ^ A b Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, p. 46. ISBN 0-304-36662-5

- ↑ Simon Singh: Secret Messages . Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2000, p. 194. ISBN 0-89006-161-0

- ↑ a b c d Friedrich L. Bauer: Deciphered secrets. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin et al. 2000, p. 419.

- ^ Marian Rejewski: How Polish Mathematicians Deciphered the Enigma . Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 3, No. 3, July 1981, p. 226.

- ^ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, p. 434. ISBN 0-304-36662-5

- ^ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, p. 422. ISBN 0-304-36662-5

- ^ Gordon Welchman: The Hut Six Story - Breaking the Enigma Codes . Allen Lane, London 1982; Cleobury Mortimer M&M, Baldwin Shropshire 2000, p. 11. ISBN 0-947712-34-8

- ^ Gordon Welchman: The Hut Six Story - Breaking the Enigma Codes . Allen Lane, London 1982; Cleobury Mortimer M&M, Baldwin Shropshire 2000, p. 16. ISBN 0-947712-34-8

- ^ A b Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, p. 357. ISBN 0-304-36662-5 .

- ^ A b Friedrich L. Bauer: Decrypted Secrets, Methods and Maxims of Cryptology . Springer, Berlin 2007 (4th edition), p. 123, ISBN 3-540-24502-2 .

- ↑ a b Rudolf Kippenhahn: Encrypted messages, secret writing, Enigma and chip card . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, p. 227. ISBN 3-499-60807-3

- ↑ a b Ralph Erskine: The Poles Reveal their Secrets - Alastair Dennistons's Account of the July 1939 Meeting at Pyry . Cryptologia. Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 30.2006,4, p. 294

- ^ Kris Gaj, Arkadiusz Orłowski: Facts and myths of Enigma: breaking stereotypes. Eurocrypt, 2003, p. 9.

- ^ Gordon Welchman: The Hut Six Story - Breaking the Enigma Codes . Allen Lane, London 1982; Cleobury Mortimer M&M, Baldwin Shropshire 2000, p. 219. ISBN 0-947712-34-8

- ^ Kris Gaj, Arkadiusz Orłowski: Facts and myths of Enigma: breaking stereotypes. Eurocrypt, 2003, p. 11.

- ^ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, pp. 381f. ISBN 0-304-36662-5

- ^ Francis Harry Hinsley, Alan Stripp: Codebreakers - The inside story of Bletchley Park . Oxford University Press, Reading, Berkshire 1993, pp. 11ff. ISBN 0-19-280132-5

- ↑ Louis Kruh, Cipher Deavours: The Commercial Enigma - Beginnings of Machine Cryptography . Cryptologia, Vol. XXVI, No. 1, January 2002, p. 11. Accessed: January 7, 2014. PDF; 0.8 MB

- ↑ a b Friedrich L. Bauer: Deciphered secrets. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin et al. 2000, p. 115.

- ^ Gordon Welchman: The Hut Six Story - Breaking the Enigma Codes . Allen Lane, London 1982; Cleobury Mortimer M&M, Baldwin Shropshire 2000, p. 214. ISBN 0-947712-34-8 .

- ↑ Friedrich L. Bauer: Deciphered secrets. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin et al. 2000, p. 50.