Polish Enigma replica

The Polish Enigma replicas are replicas of the German Enigma rotor key machine . They were manufactured in the 1930s by the Warsaw AVA factory on behalf of the Polish cipher bureau and were used by Polish cryptanalysts as clones of the German machine. They helped them with the cryptanalytic elucidation of the German methods and with the successful deciphering of the German radio messages encrypted with the Enigma in Poland from 1933 to 1939 and then in French exile .

prehistory

When the German military learned in 1923 from British publications such as Winston Churchill's The World Crisis and the "Official History of the First World War" published by the Royal Navy after losing World War I , the encryption methods they had previously used, such as code books , ADFGX and ADFGVX , which had been broken by the Allies during the war , absolutely wanted to avoid a repetition of this cryptographic catastrophe (see also: History of Enigma and History of Cryptography in the First World War ). So they looked for a replacement for these old and now unsafe manual methods. For this purpose, machine encryption came into consideration, which had been invented independently of one another in many different places around the world between 1915 and 1919. In Germany it was Arthur Scherbius who had already registered his first patent in the German Empire in 1918, during the time of the First World War . He named his machine "Enigma" (from the Greek αἴνιγμα ainigma for " riddle ") and quickly followed up the first patent with an abundance of other domestic and foreign Enigma patents and publications.

In 1928, the German army finally decided to use the Scherbius machine on a trial basis after adding a secret additional device, the plug board , to the then most modern commercial version, the Enigma D , and thus cryptographically strengthening it (see also: cryptographic strengths of Enigma ). All commercial models then disappeared from the civilian market in Germany. The machine, which was used regularly and exclusively by the Reichswehr from 1930 onwards , was called the Enigma I (read: "Enigma Eins") and embodied one of the most modern and secure encryption methods in the world at the time.

In July 1928, Polish listening stations located near Poland's western border intercepted strange new encrypted German radio messages for the first time. Only a little later, in January 1929, the Polish cipher office, Biuro Szyfrów (BS) , came into physical contact with the Enigma for the first time. The trigger was an attentive Polish customs officer who was startled by a German embassy employee. He excitedly reported that an important parcel from Germany, addressed to the German embassy in Warsaw, had been sent by mistake via the normal post instead of diplomatic baggage and insisted that it should be given to him immediately or returned immediately. The Polish official reacted with presence of mind, pretending that there was nothing he could do over the weekend, but that he would take care of the matter and make sure that this obviously very important package was returned to the sender as soon as possible next week. After the German had left calmly, the BS was informed, which sent his two employees Antoni Palluth and Ludomir Danilewicz to the customs office and to inspect the package.

They opened the heavy wooden box and found, carefully wrapped in straw, a treasure more valuable than the Polish cryptanalysts could have dreamed of. It was a brand new Enigma machine. The two used the whole weekend to carefully examine the German machine and record its details. Afterwards, they repackaged them exactly as they found them before the package - as requested - was sent back on Monday. It was never known that the Germans suspected or noticed that their secret cryptographic machine had been subjected to such a careful inspection.

The findings of the BS were rounded off after the Poles received copies of the Enigma manuals in December 1931 from the French secret service agent Capitaine (German: "Captain") and later Général Gustave Bertrand . These were the instructions ( H.Dv. g. 13) and key guidance (H.Dv.g.14) of the German cipher. The Deuxième Bureau of the French secret service had received this from the German Hans-Thilo Schmidt, who spied for France under the code name HE ( Asché ) . In further meetings, Schmidt delivered top-secret keyboards for the months of September and October 1932 to Bertrand, which were also forwarded to the BS by return of post .

All this was not enough to break the encrypted German radio traffic - the Enigma still proved to be "unbreakable" - but it was an important foundation stone for the deciphering successes that followed soon.

First decipherment

On September 1, 1932, the BS4 department responsible for the German ciphers was relocated from Posen to Warsaw in the Saxon Palace (Polish: Pałac Saski ) . With him came the three young mathematicians Marian Rejewski , Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski . In the same year, Rejewski and his colleagues succeeded in breaking into the machine used by the German Reichswehr to encrypt their secret communications. He used a legally purchased commercial machine (model D), in which - unlike the military Enigma I, which was still unknown to him - the keyboard was connected to the entry roller in the usual QWERTZ order (letter sequence on a German keyboard , starting at the top left) . Rejewski guessed the wiring sequence chosen by the Germans for the military variant, which in 1939 almost drove the British codebreaker Dillwyn "Dilly" Knox to despair. Then, with the help of his excellent knowledge of permutation theory (see also: Enigma equation ), Marian Rejewski managed to understand the wiring of the three rollers (I to III) and the reversing roller (A) (see also: Enigma rollers ) - a cryptanalytic masterpiece that made him the words of the American historian David Kahn "in the pantheon of the greatest cryptanalysts of all time rises" (in the original: "[...] elevates him to the pantheon of the greatest cryptanalysts of all time"). The British code breaker Irving J. Good designated Rejewskis performance as "The theorem did won World War II" (German: "The theorem that won World War II").

But even this success of the BS , impressive and important as it was, was still not enough to routinely break the German radio messages . But the Polish code breakers had cleared up all the technical details of the German machine at the beginning of 1933, they knew its structure and in particular the top secret wiring of the three rotating rollers (I to III), the entry roller ( ETW) and the reversing roller (UKWA).

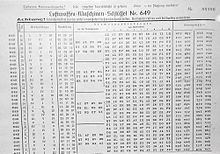

ETW A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

I E K M F L G D Q V Z N T O W Y H X U S P A I B R C J

II A J D K S I R U X B L H W T M C Q G Z N P Y F V O E

III B D F H J L C P R T X V Z N Y E I W G A K M U S Q O

UKW A AE BJ CM DZ FL GY HX IV KW NR OQ PU ST

This knowledge finally enabled the Poles to recreate the Enigma I used by the Reichswehr and strengthened with the plug board .

Replicas

In February 1933, the BS commissioned the AVA plant in the southern Warsaw district of Mokotów at 25 Stepinska Street (Polish: Ulica Stepinska 25 ) to manufacture replicas of the reconstructed military Enigma I. The Wytwórnia Radiotechniczna AVA (German: Radio technology factory AVA) was founded four years earlier, in 1929, on the initiative of Edward Fokczyński together with Antoni Palluth and the two brothers Leonard Danilewicz and Ludomir Danilewicz . At least 15 Enigma replicas were made here by mid-1933. Around 70 pieces had been produced by 1939.

After the German invasion of Poland in 1939 and the German offensive against France that took place a year later , the Polish cryptanalysts fled to Zone libre , the free southern zone of France, and continued their successful work at Uzès in the new location "Cadix" from October 1940 . Bertrand took care of the production of further Enigma replicas with the help of French companies. A copy of it has been preserved and is on display at the Józef Piłsudski Institute in London (see color photo at the top).

Further successes in deciphering

The cryptanalytic successes of the BS4 could be continued continuously until 1939 , despite the cryptographic complications that were repeatedly introduced by the German side in the following years , while at the same time French and British authorities tried in vain to decipher the Enigma. In addition to the Enigma replicas, the Polish specialists, under the leadership of Antoni Palluth, had in the meantime also constructed two machines specifically used for deciphering , called the cyclometer and bomba , which embodied two or three times two Enigma machines connected in series and each shifted by three rotary positions. Shortly before the German attack on Poland and in view of the acute threat of danger, the Polish General Staff , headed by Generał brygady (German: Brigadier General ) Wacław Stachiewicz , decided to hand over all of their knowledge of the German machine's deciphering methods to the British and French allies , and had the British and French invited to the Polish capital through the BS in July 1939.

On July 26 and 27, 1939, the secret meeting of Pyry took place in the Kabaty Forest, about 20 km south of Warsaw , at which the Polish code breakers disclosed their methodologies to the amazed British and French and handed over two Enigma replicas. This laid the foundation stone for the historically significant Allied Enigma decipherments (code name: "Ultra" ) during the Second World War.

In exile

In September 1939, after the start of the war, all BS employees had to leave their country. Most fled via Romania and eventually found asylum in France . Most of their documents and cryptanalytic machines, including the replicated enigmas, they destroyed or buried so that they would not fall into German hands. One of the few specimens that was saved was brought by the young Kazimierz Gaca during his five-month escape between 1939 and 1940 from Poland via Romania, Yugoslavia and Greece to France. In the Château de Vignolles ( German castle Vignolles ) in Gretz-Armainvilliers , about 30 kilometers southeast of Paris, he found a new base along with many of his colleagues. There they were able to continue the successful cryptanalytic work against the Enigma in the " PC Bruno ", a secret intelligence service facility of the Allies . With the German offensive against France in June 1940, they had to flee again from the advancing Wehrmacht and found a new location (camouflage name: "Cadix" ) near Uzès in the free southern zone of France (zone libre) .

literature

- Friedrich L. Bauer : Deciphered Secrets. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin a. a. 2000, ISBN 3-540-67931-6 .

- Gustave Bertrand : Énigma ou la plus grande enigme de la guerre 1939–1945 . Librairie Plon, Paris 1973.

- Gilbert Bloch, Cipher Deavours: Enigma before Ultra - The Polish Success and Check (1933-1939). Cryptologia , Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 11.1987,4, pp. 227-234.

- Ralph Erskine : The Poles Reveal their Secrets - Alastair Dennistons's Account of the July 1939 Meeting at Pyry . Cryptologia. Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 30.2006,4, pp. 294-395. ISSN 0161-1194 .

- John Gallehawk: Third Person Singular (Warsaw, 1939) . Cryptologia. Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 3.2006,3, pp. 193-198. ISSN 0161-1194 .

- David H. Hamer, Geoff Sullivan, Frode Weierud : Enigma Variations - An Extended Family of Machines . In: Cryptologia . Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 22.1998,3, pp. 211-229. ISSN 0161-1194

- Francis Harry Hinsley , Alan Stripp: Codebreakers - The inside story of Bletchley Park . Oxford University Press, Reading, Berkshire 1993, ISBN 0-19-280132-5 .

- David Kahn : Seizing the Enigma - The Race to Break the German U-Boat Codes, 1939-1943 . Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, USA, 2012, pp. 92f. ISBN 978-1-59114-807-4

- David Kahn: The Polish Enigma Conference and some Excursions . Cryptologia. Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 29.2005,2, pp. 121-126. ISSN 0161-1194 .

- Philip Marks , Frode Weierud: Recovering the wiring of Enigma's reverse roller A . In: Cryptologia . Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 24.2000.1, pp. 55-66. ISSN 0161-1194 .

- Dermot Turing : X, Y & Z - The Real Story of how Enigma was Broken. The History Press , Stroud 2018, ISBN 978-0-75098782-0 .

- Gordon Welchman : The Hut Six Story - Breaking the Enigma Codes . Allen Lane, London 1982; Cleobury Mortimer M&M, Baldwin Shropshire 2000, ISBN 0-947712-34-8 .

Web links

- Photo of a Polish replica in the Crypto Museum. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- Polish Enigma replica (English description and simulation program) Accessed: December 11, 2015.

- Secret operation Wicher of the Polish secret service with a photo of a Polish Enigma replica. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- The Breaking of Enigma by the Polish Mathematicians in the BP virtual museum (English). Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- The Invention of Enigma and How the Polish Broke It Before the Start of WWII (PDF; 0.2 MB) by Slawo Wesolkowski (English). Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- History of the Enigma in the Crypto Museum (English). Retrieved October 30, 2015.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Simon Singh: Secret Messages . Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2000, p. 177. ISBN 3-446-19873-3

- ^ Karl de Leeuw: The Dutch Invention of the Rotor Machine, 1915-1923 . Cryptologia. Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 27.2003,1, pp. 73-94. ISSN 0161-1194 .

- ↑ Louis Kruh, Cipher Deavours: The Commercial Enigma - Beginnings of Machine Cryptography . Cryptologia. Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 26.2002,1, pp. 1-16. ISSN 0161-1194 .

- ↑ Arthur Scherbius: "Enigma" cipher machine . Elektrotechnische Zeitschrift, 1923, p. 1035.

- ^ Rudolf Kippenhahn: Encrypted messages, secret writing, Enigma and chip card . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, p. 211. ISBN 3-499-60807-3

- ↑ Simon Singh: Secret Messages . Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2000, p. 178. ISBN 3-446-19873-3

- ^ Marian Rejewski: How Polish Mathematicians Broke the Enigma Cipher . IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 03, No. 3, July 1981, pp. 213-234.

- ^ Friedrich L. Bauer: Historical Notes on Computer Science . Springer, Berlin 2009, p. 172. ISBN 3-540-85789-3

- ^ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, pp. 22-23. ISBN 0-304-36662-5

- ↑ OKW: Instructions for use for the Enigma cipher machine . H.Dv.g. 13, Reichsdruckerei , Berlin 1937, superborg.de (PDF; 2.0 MB) accessed April 22, 2015.

- ↑ OKW: Key instructions for the Enigma key machine . H.Dv. G. 14, Reichsdruckerei , Berlin 1940. (Copy of the original manual with a few small typos.) Ilord.com ( Memento from September 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 10 kB) accessed April 22, 2015.

- ^ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, p. 22. ISBN 0-304-36662-5

- ^ Gordon Welchman: The Hut Six Story - Breaking the Enigma Codes . Allen Lane, London 1982; Cleobury Mortimer M&M, Baldwin Shropshire 2000, p. 210. ISBN 0-947712-34-8

- ^ Marian Rejewski: An Application of the Theory of Permutations in Breaking the Enigma Cipher . Applicationes Mathematicae, 16 (4), 1980, pp. 543-559. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- ↑ Friedrich L. Bauer: Deciphered secrets. Methods and maxims of cryptology. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin a. a. 2000, p. 114.

- ^ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma - The battle for the code . Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, p. 42. ISBN 0-304-36662-5

- ^ Frank Carter: The Polish Recovery of the Enigma Rotor Wiring . Publication, Bletchley Park, March 2005.

- ↑ David Kahn: Seizing the Enigma - The Race to Break the German U-Boat codes 1939 -1943 . Naval Institute Press, Annapolis MD 2012, ISBN 978-1-59114-807-4 , p. 76.

- ^ IJ Good, Cipher A. Deavours, afterword to Marian Rejewski: How Polish Mathematicians Broke the Enigma Cipher . IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 03, No. 3, pp. 213-234, July 1981, pp. 229 f.

- ↑ Chris Christensen: Review of IEEE Milestone Award to the Polish Cipher Bureau for `` The First Breaking of Enigma Code '' . Cryptologia . Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 39.2015,2, p. 185. ISSN 0161-1194 .

- ^ Krzysztof Gaj: Polish Cipher Machine -Lacida . Cryptologia. Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 16.1992,1, ISSN 0161-1194 , p. 74.

- ^ Friedrich L. Bauer: Historical Notes on Computer Science . Springer, Berlin 2009, p. 301. ISBN 3-540-85789-3

- ↑ a b Ralph Erskine: The Poles Reveal their Secrets - Alastair Dennistons's Account of the July 1939 Meeting at Pyry . Cryptologia. Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Taylor & Francis, Philadelphia PA 30.2006,4, p. 294

- ^ Dermot Turing: X, Y & Z - The Real Story of how Enigma was Broken. The History Press, 2018, ISBN 978-0-75098782-0 , p. 141.