Polish citizenship

The Polish nationality or citizenship ( Polish obywatelstwo polskie ) is the association of a natural person to the Republic of Poland , in the Constitution was regulated and citizenship laws of 1920, 1951, 1962 and 2009 and will.

Development in the 20th century

In the tsarist empire , those living in the Vistula were Russian subjects . However, there were certain special rights that were gradually restricted after the uprisings. Polish Jews were prohibited from moving to regions outside the Pale of Settlement until 1881 .

Consequences of the Versailles Treaties

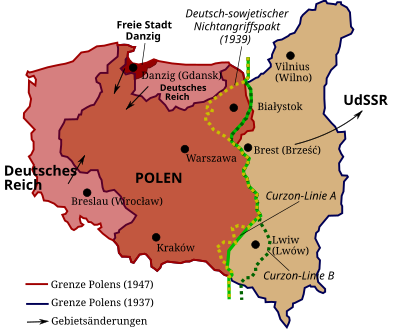

Green Line : proclaimed by the Western Allies on December 8, 1919 as the demarcation line between Soviet Russia and the Second Republic of Poland, Curzon Line based on the ethnographic principle.

Blue Line : after the end of the First World War until 1922 through the conquests of Poland under General Józef Piłsudski (Eastern Galicia 1919, Wolhynia 1921 and Vilnius Area 1922) across the Curzon Line, which existed until September 17, 1939.

Yellow line : German-Soviet demarcation line from September 28, 1939.

Red line : today's state border of Poland; left the Oder-Neisse line.

Brown area : area expansion carried out by Poland after the end of the First World War until 1922, which had previously been recognized by the Soviet Union.

Pink area : Eastern areas of the German Reich asserted by Stalin in 1945 for Poland as compensation for the loss of the areas east of the Curzon Line (" west shift " had an impact on the citizenship of several million people).

Especially in the area of state succession , new territory in international law was broken, the results of which are still part of the foundations of worldwide (custom) international law. One principle is that residents of a ceded area receive the new citizenship.

A separate Polish citizenship only came into being through the agreement of June 28, 1919, the so-called Little Versailles Treaty .

Citizenship Act of 1920

The Citizenship Act of January 20th came into effect on January 31st. It was followed by the ius sanguinis , in connection with the principle of family unity, i.e. H. Wives and underage children followed the man's nationality. Dual citizenship was prohibited.

According to the Polish law , those residents of the new national territory who were either entered in the formerly Russian population registers at the time the law was promulgated, had Austrian or Hungarian national law in the Galician territories or were German citizens before January 15, 1908, had their permanent residence in the formerly Prussian territories Areas had. For Teschener Silesia the deadline was November 1st, 1918.

In addition, stateless people born in the area and foundlings.

Poles abroad and their descendants could acquire citizenship by declaring after taking up residence in Poland . A Polish woman living in the country, who had lost her citizenship through marriage to a foreigner, was able to declare her acceptance again after the marriage.

Normal reasons for employment were the marriage of a foreigner to a Polish man and the birth of a child to Polish parents, adoption or recognition of paternity. Poles also became civil servants when they were appointed or serving as professional soldiers, unless a corresponding reservation was made.

Naturalizations extended to minors under the age of 18. Requirements were:

- impeccable reputation

- adequate income

- Polish language skills

- ten years residence in the country

Individual conditions could be waived for residents of the formerly Russian parts of the empire.

The Minister of the Interior approved naturalizations after the authorities of the municipality of residence of the applicant had given their opinion.

The reason for loss was the acceptance of a foreign citizenship. When joining a foreign army or dismissing a (still) conscript, the consent of the city commissioner of Warsaw or the responsible military district commander was required.

Special rules

Members of the losing states who had their permanent residence in the now Polish areas before January 1, 1919 (Germans 1908) automatically became Polish citizens. However, they were given an option right for their former home countries. If they did this, this included wife and children. In return, this also applied to Poles living abroad. If the respective option was exercised, the optants had to move to their new home country within twelve months. The peace treaty of Riga (1921) regulated the same for Russians in Articles 6 and 7. Initially, all former tsarist subjects residing on Polish territory when the treaty was concluded automatically became Poles if they had their residence there on August 1, 1914. This group of people received an option right for Soviet Russia or the Ukrainian People's Republic , which was to be exercised until April 30, 1922.

For former kuk subjects, especially in Galicia, the following was true: those who had had their homeland rights there at the time of the war had to automatically acquire citizenship. There was a six-month option period for other possibly possible citizenships with the requirement to move within one year of exercise.

Due to the aggressive polonization policy of the dictatorial regime of Marshal Józef Piłsudski , there were repeated attempts to incorporate other areas, such as the Free City of Danzig, which created its own nationality .

The Vilnius area , the residents of which had acquired Lithuanian citizenship , came under Polish administration.

Individual international treaties brought further agreements and option rules, often only after years.

- Upper Silesia from 1921/2

The changing ideas of the League of Nations on the assignment or division of Upper Silesia, the pro-German result of the referendum of March 20, 1921, and the attempt by France to weaken Germany led to different approaches. Citizenship issues were also regulated here by the German-Polish treaty concluded in Geneva on May 15, 1922 , which came into force one month later with the border regulation. The liquidation question only affected German nationals who remained in the ceded areas, so the Reich had an interest in many of its citizens becoming Poles. However, that country insisted on the provision of Article 91 of the Versailles Treaty, which was disadvantageous for Germans, according to which those who had moved here after January 1, 1908, were excluded from acquiring Polish citizenship. These Germans could opt for Poles within six months, otherwise they remained Germans. Here Poland insisted on uninterrupted main residence in the region. The 1922 treaty, however, provided relief for those who participated in the war (as conscripts), training purposes, long stays in other areas ceded to Poland, etc. For those born between January 1, 1919 and June 15, 1922, questions arose about dual citizenship, which both states did not want.

1939 to 1946

After the Polish state collapsed on September 17, 1939, the Soviet power began to organize new West Ukrainian and West Belarusian districts. After elections for the people's assembly on October 22nd, the residents were given the opportunity to attend the 1./2 Nov. 1939 granted Soviet citizenship by ordinance (according to the Citizenship Act 1938 ), with the exception of the Vilna area, which was ceded to Lithuania.

Particularly complex conditions arose for residents of the eastern areas under different types of administration. If possible from a racial point of view, groups of German origin could in turn be naturalized and settled or brought back to the Reich.

It is worth mentioning the British Polish Resettlement Act 1947. As a result, a large number of the more than 200,000 Poles in exile who fought with the allies in the west became British subjects. This measure was done less for humanitarian reasons, but had the solid background that manpower for the reconstruction could be won over permanently, whereby the war losses of young English men could be compensated.

People's Republic of Poland

In 1947 Poland defined the right to citizenship along ethnic lines; H. the few non-Poles who had not been evacuated between 1945 and 48 had, if they had their place of residence on September 1, 1939, to prove their nationality before a committee. It was helpful here if a German lived in the country as a member of the working class or had a sought-after job. The still widespread idea that a “real Pole” had to be Catholic was particularly useful for those who were not (yet) displaced in Silesia. Those naturalized in this way formed the core of the Spätaussiedler in later decades .

A total of three agreements with the Soviet Union before 1957 regulated the relocation of certain groups of people to Poland.

Nationality Act 1951

The fundamental changes in citizenship law took account of the progress made in socialism. The nationality of the wife was no longer dependent on that of her husband, so that foreign women marrying in no longer automatically became Polish. Likewise, the legitimate children no longer acquired the nationality of the father while illegitimate children acquired the nationality of the mother. Returning Poles were now automatically (again) citizens, the declaration requirement no longer applies. The acceptance of foreign citizenship now had to be approved in all cases.

Persons who were Polish citizens living in Poland when the war broke out were no longer considered Poles if they were living abroad when the law came into force on January 19, 1951 and had since been granted Soviet or German citizenship because of this or on the basis of an agreement.

Children acquired citizenship from birth if both parents were Polish, or if one parent was Polish and the other was stateless or with unclear citizenship. Mixed married couples with a foreign residence were allowed to opt for foreign citizenship if this was permitted under foreign law.

The Council of State now decided on naturalizations . The (punitive) withdrawal was possible.

To avoid dual statehood , the VR Poland concluded agreements with the Soviet Union and some brother countries, which granted those affected an option period for one of the two nationalities.

These agreements were all terminated in 1999 with effect from 2002.

A good sixty percent of the Lemks , an ethnic group of the Carpathian-Ukraine speaking a dialect of Little Russian , stayed in the area that was divided between the Soviet Union and Slovakia after the war. It was not until 1956 that their resettlement was regulated. In 1957/8 about 5000 families returned, assuming Polish citizenship. Only a part made it back to Lemkenland , many others were assigned places of residence in formerly German villages in northern Poland or western Prussia.

Nationality Act 1962

The new Citizenship Act February 15, 1962 was more detailed than its predecessor. Citizenship issues were dealt with by the Ministry of Interior at voivodship level, of which there were 49. Naturalizations were then officially granted by the State Council.

The provisions on acquisition by birth remained essentially unchanged. Foreigners marrying in could become Polish women within three months by submitting a corresponding declaration. This was later changed so that a spouse could only make this declaration within six months after three years of marriage.

The naturalization requirements were:

- 5 years residence in the country (later: 5 years permanent or EU citizen residence permit)

- Abandonment of other nationalities

Underage children had to consent from the age of 16. Naturalizations of only one parent only extended to minor children if that parent had custody.

It was later regulated that in the case of mixed-national couples the other parent had to agree. Furthermore, naturalizations only extended to underage children if they lived with their parents in Poland.

With regard to re- naturalization, it was redefined that people who had lost their Polish citizenship between 1919 and the entry into force of the law in 1951 because they served in a foreign army or had changed their citizenship without authorization could not be naturalized again. People who left and changed after 1951 were allowed to be naturalized again.

Withdrawal was possible for people living abroad:

- if they left the country illegally after May 9, 1945 or

- acted against the interests of the Polish government and otherwise behaved somehow disloyal

- did not return home despite official requests

- failed to do their military service

Poles abroad with foreign, second citizenship were often forced to formally renounce their Polish citizenship when visiting their home country.

Legislative changes Much discussed, the 1962 law remained in force even after the system change; the last change took place in 2007. Responsibility for naturalization passed from the State Council to the President. Applications, including those for dismissals, were initially to be sent to the governor ("voivode") of the now 16 voivodships. This forwarded his preliminary decision to the Interior Minister.

Various changes adapted individual rules to the circumstances of the new era. Recognized refugees had to be taken into account after joining the Refugee Convention in 1991 and creating a right of asylum for the first time.

In the context of gender equality, the naturalization right of a woman marrying in has been abolished. Changes in citizenship did not affect that of the partner.

Since 1997, the assumption of a foreign citizenship no longer automatically led to the loss of Polish citizenship.

Due to the economic crisis of the 1990s and then joining the EU in 2004 , the status of emigrants and returnees had to be clarified. In particular, the mandatory release permit prior to assuming a foreign nationality and the continued ban on dual nationals developed into problems. This happened for the first time with the 2000 regulation.

Since 2009

As early as 1999/2000, a reform of citizenship law began to be debated in parliament, but this did not produce any results for years.

The Citizenship Act passed in 2009 did not come into force until mid-2012. Above all, the reform should give preference to those from the diaspora willing to return. The principle “Poles for Poles” is generally retained in foreign policy.

Acquisition of citizenship

- Acquisition by birth

Polish citizenship is usually acquired according to the principle of descent ( ius sanguinis ). A child thus acquires according to Art. 14 para. 1 of the law on citizenship automatically at birth the Polish nationality , provided that at least one of the parents is a Polish citizen. Stateless persons (Art. 14, Paragraph 2) and foundlings (Art. 15) acquire Polish citizenship ( ius soli ) solely through their place of birth in Poland .

- naturalization

Polish citizenship can either be granted to a foreigner by the President of the Republic , or its existence can be determined by a voivod .

Traditional and acc. Art. 137 of the Polish Constitution, foreign nationals are granted Polish citizenship by the President of the Republic of Poland . A corresponding application must therefore be made directly to the head of state. This decides on citizenship issues entirely at its own discretion. As the head of state's prerogative, the decision is not subject to judicial review. Until the Citizenship Act of 2009 came into force, this was the only way to obtain Polish citizenship.

However, naturalization was fundamentally re-regulated by the Citizenship Act of 2009: It is now possible to apply for the “determination of Polish citizenship” by the locally competent voivode . In contrast to the proceedings before the President, is in the process before the Voivod to a decent (thus u. A. To deadlines bound and legally verifiable) administrative procedures , in which the officials only check if one of the requirements of Art. 30 of the Citizenship Law is given :

- The foreigner has been living as a resident (see settlement permit ) in Poland for at least three years , has a stable source of income and a legal title to the inhabited restaurant (e.g. rental agreement).

- The foreigner has been living legally in Poland for at least 10 years and now has the right of permanent residence, as well as a stable source of income and a legal title to the inhabited restaurant.

- The foreigner has lived for at least two years as a resident in Poland and is a Polish citizen for at least three years married .

- The foreigner has been resident in Poland for at least two years and is stateless .

- The foreigner has been living in Poland as a refugee for at least two years .

- The foreigner has been returning to Poland for at least two years .

In this procedure, one speaks of the determination and not of the award, since the latter according to Art. 137 of the Polish Constitution may only be made by the President. In 2009, Lech Kaczyński, as the then President , initiated an abstract judicial review procedure before the Constitutional Court , which, however, dismissed the complaint on January 31, 2012 and confirmed the constitutional conformity of the law.

The granting of Polish citizenship to both parents extends according to Art. 7 para. 1 of the Citizenship Act ex lay on the children who remain under their parental authority.

- Recovery

If only one parent has Polish citizenship, the parents can decide up to the third month after the child's birth that the child should only have the other, not Polish, citizenship. However, this child will then have the option of regaining Polish citizenship between the ages of 16 and 18½ years.

A Polish citizen who has lost Polish citizenship after marrying a foreigner can regain it if the marriage is annulled or the marriage is divorced.

All applications for regaining citizenship of people living abroad must be submitted to the Polish consul.

Loss of citizenship

Loss of Polish citizenship is only possible through personal renunciation. The person concerned is required to submit a corresponding written application to the Polish President, who in turn must give his consent.

It is therefore not possible to lose Polish citizenship by adopting another citizenship and / or not renewing or losing the Polish passport. If a Polish citizen emigrates to another country , who takes on the citizenship and fails to renew his Polish passport because he only uses the other passport, his Polish citizenship will still be automatically retained and he can apply for a Polish passport at any time.

During the People's Republic , emigrants to the Federal Republic of Germany were deprived of their Polish citizenship. On the other hand, the governments of the People's Republic and the GDR signed a treaty on dual citizenship for certain groups of resettlers who were officially called resettlers in the GDR .

Effects of the legal situation before and after August 21, 1962

Those Polish citizens who had left the Polish state before that day and who took on another citizenship had to give up their Polish citizenship as a precondition for their exit permit. All those who left Poland after that day, in spite of the waiver, theoretically retained their Polish citizenship. This clarified a judgment of the Supreme Administrative Court of the Republic of Poland.

The Constitutional Court in Warsaw complained in 2000, the practice of the authorities of the People's Republic that even after the entry into force of the new law from 1962 repatriates on exit in West or East Germany the task of Polish citizenship had been demanded. This was unlawful, but was an administrative practice approved by ordinance from 1956–84. According to Section 40 of the decree on Polish citizenship of April 2, 2009, these affected repatriates can be re-granted upon application.

Multiple citizenship

In accordance with Article 3 of the Citizenship Act, a Polish citizen is treated as such by the Polish authorities, irrespective of whether there is multiple nationality . This means that such a person can not evade Polish law or corresponding civic obligations (e.g. military service ) by invoking their foreign nationality.

Since Poland joined the EU on May 1, 2004, German citizens no longer have to give up their citizenship if they want to become Polish citizens. Conversely, according to Section 87 (2) of the German Aliens Act, it was possible for citizens of Poland to become German citizens without having to give up their Polish citizenship.

After the expiry of the German Aliens Act (AuslG) on December 31, 2004, this exception from the avoidance of multiple citizenship is legally in effect in Section 12 (2) of the Citizenship Act (StAG): From the requirement of Section 10 (1) sentence 1 no 4 (giving up or losing the previous citizenship) is also waived if the foreigner is a citizen of another member state of the European Union or Switzerland.

Excerpts from the Constitution of the Republic of Poland

- Art. 34 Polish Constitution of 1997

- (1) Polish citizenship is acquired through the birth of parents of Polish citizenship. The law regulates other cases of acquisition of Polish citizenship.

- (2) A Polish citizen may not lose his or her Polish citizenship unless he or she renounces it himself.

- Art. 137

- The President of the Republic of Poland recognizes Polish citizenship and gives consent to renounce Polish citizenship.

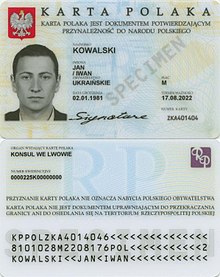

"Karta Polaka"

Since 2008 it has been possible to apply for a “Karta Polaka” ( Poland card ) for ethnic Poles who are citizens of other states or apatrids (until 2019 only citizens of the successor states of the former Soviet Union were eligible) and who can prove that they have Polish ancestry and language skills as well as declare their Polish ethnicity in writing. The cardholders do not have Polish citizenship, but have various privileges vis-à-vis other foreigners, e.g. with an entry visa, gainful employment, education or health care in Poland.

statistics

Between 1993 and 2002, the number of naturalizations fluctuated around 600 to 1000. In the years 2003–05, their number rose to 2,625, and then quickly fell again. The reason for this was the lifting of the ban on dual nationals for citizens of the Eastern Bloc. Since 2010, the number of annual naturalizations has been between three and four thousand.

The number of “returnees”, including those mainly from former Soviet republics, was mostly just under 300 in 1997–2006, with the exception of 2000–01 with the peak 804 when numerous Kazakhs and Ukrainians came.

The forthcoming EU accession in 2004 resulted in a sharp increase in the number of citizenship certificates applied for abroad: 2000: 765 applications; 2004: 3807; 2005: 505 from Argentina alone.

In the 2002 census, a good 445,000 people claimed to be entitled to a second citizenship, around 280,000 of whom saw themselves as Germans.

See also

literature

- Armand Ackerberg: Rights and duties of foreigners in Poland. Laws, ordinances, international agreements, court decisions, etc. Heymann, Berlin 1933.

- Georg Geilke : Nationality Law of Poland. Metzner, Berlin 1952.

- Agata Górny, Dorota Pudzianowska: Report on Poland. Badia Fiesolana, San Domenico di Fiesole 2013 (CADMUS).

- Max Kollenscher : Polish citizenship. Your acquisition and content for individuals and minorities. Shown on the basis of the State Treaty of June 28, 1919 between the main Allied and Associated Powers and Poland . Bahlen, Berlin 1920.

- [Government Councilor] Werner Köppen: Gdansk citizenship law together with the laws and other provisions on the acquisition and loss of citizenship in Germany, Poland, Russia, Lithuania, Memels, Estonia, Latvia and Finland. Gdansk 1929.

- Walter Schätzel [1890–1961]: The change of nationality as a result of the German assignment of territory. Explanation of the articles of the Versailles Treaty regulating the change of nationality, together with a copy of the relevant contractual and legal provisions. Berlin 1921 [Addendum 1922 udT: The change of nationality as a result of the German assignment of territory: Explanation of the articles of the Versailles Treaty regulating the change of nationality, together with a copy of the relevant contractual and legal provisions. Addendum containing a compilation and explanation of the new citizenship regulations for the Saar region, Upper Silesia, Danzig and North Schleswig, as well as an overview of the citizenship regulations of the other peace treaties of the World War. ].

- Udo Rukser : Citizenship and Protection of Minorities in Upper Silesia. Publishing house for politics and economy, Berlin 1922.

- Christian Th. Stoll: Legal status of German citizens in the Polish administered areas. To integrate the so-called autochthons into the Polish nation. Published by the Johann-Gottfried-Herder-Forschungsrat e. V., Metzner, Frankfurt a. M./Berlin 1968, DNB 458253553 .

- Ewa Tuora-Schwierskott: Polish and German Nationality Law. Legal texts with translation and introduction = Polska i niemiecka ustawa o obywatelstwie. de-iure-pl, Regensburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-9814276-7-7 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Polish Citizenship Act of 1920 ( Memento of February 3, 2014 in the Internet Archive ). In: yourpoland.pl .

- ↑ a b Polish Nationality Act of 1951 ( Memento of August 22, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) (ed.); Polish full text: Dziennik Ustaw, No. 4, item 25 . German see Geilke (1952).

- ↑ a b Polish Nationality Act of 1962 ( Memento of January 13, 2012 in the Internet Archive ). In: yourpoland.pl .

- ^ Kancelaria Sejmu RP: Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych. Retrieved August 22, 2017 .

- ↑ For the group of people included, see also Question Concerning the Acquisition of Polish Nationality ( Memento of July 13, 2020 in the Internet Archive ). Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) (ser. B) No. 7 (September 15, 1923). In: worldcourts.com, accessed July 22, 2020.

- ↑ The aim was to exclude newcomers who came under the aegis of the “Settlement Commission for West Prussia and Posen” and the few profiteers from the Prussian expropriation law to the detriment of poorly managed Polish businesses.

- ↑ Defined not in terms of parentage, but rather "national activity" (Upper Silesia Agreement, Art. 27, § 3).

- ↑ Treaty of Saint-Germain : VI: Provisions concerning citizenship. ( State Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye of September 10, 1919 ) and analogously in the Treaty of Trianon , Section VII.

- ↑ From a Lithuanian point of view, it remained under Polish occupation from 1919/20 until October 1939 (see Treaty of Suwałki and the Polish-Lithuanian War ). Residents living here in 1939, who would have been entitled to Lithuanian citizenship in 1920, became Lithuanians in November 1939, and then Soviet people in June 1940.

- ↑ For example: 1) Umowa pomiędzy rzecząpospolitą Polską a republiką Czeskosłowacką w przedmiocie obywatelstwa i spraw z niemiązanych; [Prague] 1920; 2) Polish-Danzig Agreement of October 24, 1921 (Sections 33–37 on minority issues and naturalization); 3a) Haase, B .; The German-Polish State Treaty on Citizenship and Options (the Vienna Agreement of August 30, 1924); Berlin 1925 (C. Heymann); 3b); Grünebaum, Gustav; The question of citizenship and options after the German-Polish agreement of August 30, 1924; Düren 1932 (Danielewski) [Diss. Würzburg]; 4) September 18, 1933. Agreement between Danzig and Poland on the treatment of Polish nationals and other persons of Polish origin or language. In: Journal for Foreign Public Law and International Law . Vol. 4 (1934), p. 134.

- ↑ RGBl. 1922 II, p. 238 ff. On this RGBl. 1922 II, p. 237 No. 10: Law on the German-Polish Agreement on Upper Silesia concluded in Geneva on May 15, 1922. (PDF; 23 kB).

- ^ Paragraph after Walter Schätzel, (1921/22).

- ↑ Microfilm of the list of names of optants in Opole: Archiwum Diecezjalne w Opolu; Option for Poland, 1922–1924. Salt Lake City, Utah 2004 (Genealogical Society of Utah).

- ↑ See Hellmut Sommer: 135,000 won the fatherland: the return of the Germans from Volhynia, Galicia and the Narew region. Nibelungen, Berlin 1940.

- ^ List of names filmed from the Federal Archives by The Genealogical Society of Utah: Immigrant File, 1939–1945. Salt Lake City, Utah 1992, 1964 rolls of microfilm.

- ↑ 1947 c. 19 (10 and 11 Geo 6)

- ↑ Relevant legal texts: 1) Ustawa z dnia 28 kwietnia 1946 r. o obywatelstwie Państwa Polskiego osób narodowości polskiej zamieszkałych na obszarze Ziem Odzyskanych. Dziennik Ustaw, No. 15, 1946, item 106 (PDF; 232 kB); 2) Decree z dnia 22 października 1947 r. o obywatelstwie Państwa Polskiego osób narodowości polskiej zamieszkałych na obszarze b. Wolnego Miasta Gdańska; [“Decree of October 22, 1947 on the citizenship of the Polish state of people of Polish nationality who live in the area of the former Free City of Danzig.”] Dziennik Ustaw, 65, 1947, item 378 (PDF; 316 kB); 4) Ordinance of the State Council No. 37/56 (1956) with regard to the permission for emigrants of German origin to take off their Polish citizenship (valid until 1984); 5) Permission for Jews emigrating to Israel to take off their Polish citizenship - No. 5/58 (1958).

- ↑ Further information: Strobel, Georg W .; Ukrainians and Lemks as a problem of national structural change and restructuring in East Central Europe after the Second World War. Cologne 1965 (reports of the Federal Institute for Research into Marxism-Leninism ).

- ↑ Ustawa z dnia 9 listopada 2000 r. o repatriacji, ["Law of November 9, 2000 on Repatriation"] Polish full text: Dziennik Ustaw, No. 4, item 25 (PDF; 3.9 MB).

- ↑ 2.1 Birth and descent: Poland ( Memento from August 22, 2017 in the Internet Archive ). In: migration-online.de, February 4, 2004.

- ^ Order of the seven judges of the Supreme Administrative Court of November 9, 1998, OPS 4/98.

- ↑ potwierdzenie posiadania lub utraty obywatelstwa polskiego. In: gov.pl. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018 ; Retrieved August 22, 2017 (Polish).

- ↑ Kp 5/09 - Akt. In: lex.pl. Retrieved August 22, 2017 .

- ↑ Rozporządzenie Prezydenta Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z dnia 14 marca 2000 r. w sprawie szczegółowego trybu postępowania w sprawach o nadanie lub wyrażenie zgody na zrzeczenie się obywatelstwa polskiego oraz wzorów zaświadczeń i wniosków.

- ↑ a b Alfons Ryborz, Deutscher Ostdienst (DOD): Bright spot in the property question. Verdict: Resettlers after August 21, 1962 retain Polish citizenship. In: The Ostpreußenblatt . Edited by Landsmannschaft Ostpreußen e. V., March 18, 2000 ( webarchiv-server.de ( Memento from August 6, 2016 in the Internet Archive )).

- ^ Mariusz Muszyński: Obywatelstwo osób przesiedlonych i repatriowanych z Polski a prawo międzynarodowe. In: Witold M. Góralski (ed.): Transfer - obywatelstwo - majątek. Trudne problemy stosunków polsko-niemieckich. Studia i dokumenty. Warsaw 2005, ISBN 83-89607-60-3 , P. 3.3.1.

- ^ Polish citizenship law 1920 ( memento of April 16, 2009 in the Internet Archive ). In: polishcitizenship.pl (English).

- ↑ Law on Polish Citizenship. In: verfassungen.eu, accessed on July 20, 2020.

- ↑ (Unpublished) Council of State Ordinance No. 37/56 (1956) with regard to the permission for emigrants of German origin to take off their Polish citizenship, this was provided and was practiced until 1984.

- ↑ Dziennik Ustaw Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej ( Memento of December 27, 2019 in the Internet Archive ) (Journal of Laws of the Republic of Poland) of February 14, 2012. In: gov.pl (with a link to the PDF Memento; 675 kB).

- ↑ Multiple citizenship in Poland (PDF; 560 kB) A. Górny, A. Grzymała-Kazłowska, P. Kory, A. Weinar, Instytut Studiów Społecznych 2003 (English).

- ↑ Multiple nationality in Germany compared to Poland and Russia. ( Memento from August 13, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 125 kB) Lisa Siebelmann & Kenan Araz, Diakonie training, March 16, 2010.

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Poland from 1997. In: sejm.gov.pl ( Polish ) ( German ).

- ^ Polish online portal for laws: Ustawa o Karcie Polaka, Dz.U. 2007 no. 180/1280 ( Memento from April 16, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (see Tekst ujednolicony) from September 7, 2007 / March 29, 2008 (Polish; PDFs no longer available).

- ↑ Chancellery of the Prime Minister: Poles living in the East can apply for Polish Charter ( Memento of April 16, 2009 in the Internet Archive ). In: kprm.gov.pl, March 29, 2008 (English).

- ↑ EUROSTAT. (No longer available online.) In: ec.europa.eu. Formerly in the original ; accessed on July 22, 2020 (English, no mementos). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives )