Agreement on the Status of Refugees

| Agreement on the Status of Refugees | |

|---|---|

| Short title: |

(unofficial) Geneva Refugee Convention (German) The 1951 Refugee Convention (English) Convention de Genève (French) |

| Title: | Convention relating to the Status of Refugees |

| Shortcut: |

(unofficial) GFK (German, FRG) FK (German, Switzerland) |

| Date: | July 28, 1951 |

| Come into effect: | April 22, 1954, in accordance with Article 43 |

| Reference: |

United Nations Treaty Series , vol. 189 , 1954, I Treaties and international agreements, p. 137-220 , no. 2545 . Online in the United Nations Treaty Collection. (PDF document; 747 KiB) A / CONF.2 / 108 / Rev.1 , November 26, 1952. United Nations Publications, Sales No .: 1951.Ⅳ.4. Online in the Official Documents System of the United Nations (PDF document; 3.26 MiB) |

| Reference (German): |

Federal Republic of Germany: Federal Law Gazette 1953 II p. 559 , on the entry into force of the agreement: Federal Law Gazette 1954 II p. 619 , on the current validity: juris : fl_abk FlüAbk Austria: Federal Law Gazette No. 55/1955 Switzerland: AS 1955 443 0.142.30 |

| Contract type: | open, multilateral |

| Legal matter: | People-computing-te , refugees |

| Signing: | 19 signatory states |

| Ratification : | including accessions and successions, there are currently 145 contracting parties

|

| Germany: | Signed: November 19, 1951, deposit of the instrument of ratification: December 1, 1953, entry into force: April 22, 1954 (without prejudice to this, the provisions of the agreement have already become legal for the Federal Republic of Germany with effect from December 24, 1953) . |

| Liechtenstein: | Signed: July 28, 1951, ratification: November 1, 1954. |

| Austria: | Signed: July 28, 1951, ratification: March 8, 1957. |

| Switzerland: | Signed July 28, 1951. Approved by the Federal Assembly on December 14, 1954 (AS 1955 441) . Swiss instrument of ratification deposited on January 21, 1955. Came into force for Switzerland on April 21, 1955. |

| The agreement was adopted by the United Nations Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Status of Refugees and Stateless Persons, which was held in Geneva from July 2 to 25, 1951. The conference was convened in accordance with resolution 429 (Ⅴ) adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 14, 1950. | |

| Please note the note on the applicable version of the contract . | |

The Geneva Refugee Convention (abbreviation GFK ; actually agreement on the legal status of refugees ) is the central legal document of international refugee law.

The GRC contains, among other things, an internationally binding legal definition of the term “ refugee ” and is the legal basis for the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

It was adopted on July 28, 1951 at a UN special conference in Geneva and entered into force on April 22, 1954. Originally, it was limited to protecting European refugees immediately after World War II.

The Convention was supplemented on January 31, 1967 by the " Protocol on the Legal Status of Refugees ", which came into force on October 4, 1967 and removed the time and geographical restrictions.

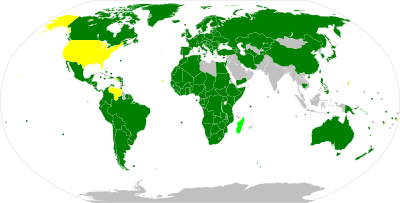

The Convention joined 146 States, the Protocol 146. 143 States have both joined the Convention and the Protocol. (As of January 25, 2014)

story

The events that led to the agreement on the NVC can be traced back to the 1920s , after western countries introduced immigration restrictions during and after World War I. The first legal developments took place with the appointment of Fridtjof Nansen as High Commissioner for Russian Refugees in 1921 and the introduction of the Nansen Pass system , which issued Russian refugees under the 1922 Agreement with a certificate of identity and thus facilitated access to residence rights. In the interwar period , the passport system was also extended to other refugees, the first definitions of the term refugee were found, the milestone of the 1933 Refugee Convention on the international status of refugees as the first binding multilateral instrument that granted refugees legal protection was achieved, and the Established 1938 Convention on the Status of Refugees from Germany. This legal framework - especially the 1933 Convention - ultimately served as the basis for the later formulation of the GRC.

Before the GFK came into force, there was no legally binding regulation on refugee law . It was only in intergovernmental agreements or in unilateral declarations of intent by individual states how many refugees a state wanted to accept in each individual case. The associated humanitarian emergencies had been recognized as a problem since the First World War . After the National Socialists came to power in Germany , the situation worsened. At the instigation of the USA , there was the Évian Conference in 1938 , which was supposed to establish admission quotas for Jews fleeing Germany . This conference was unsuccessful and showed that refugee issues could not be resolved with intergovernmental agreements. In the following decades the idea of an international convention that would grant refugees personal protection rights spread. These considerations resulted in the NVC.

As a supplement to the GRC, the regional refugee convention of the Organization for African Unity in Addis Ababa was concluded by African states in September 1969 . From the African experiences with liberation wars, civil wars, coups d'état, religious and ethnic conflicts as well as natural disasters, a significantly broader definition of the refugee is chosen and placed under protection.

In 1984, ten Latin American countries adopted the Cartagena Declaration , which was not binding at the time , and which, similar to the African Convention, deals with Latin American peculiarities and is now part of customary law as an applied state practice. All three conventions serve as the basis for international human rights for refugees.

By the year 2000, one hundred and forty countries had signed the convention and the additional protocol of 1967, even though, as former UNHCR employee Gilbert Jaeger commented in 2003, the convention had repeatedly been the target of considerable criticism.

Contents of the 1951 Convention

The GRC does not grant the right to asylum, i.e. it does not establish any entry rights for individuals, it is an agreement between states and standardizes the right to asylum, not to asylum. Refugees within the meaning of the Convention are defined as persons who are staying outside of the state of which they are citizens because of a well-founded fear of persecution , as well as stateless persons who are therefore outside their habitual state of residence. Contrary to popular belief, the Geneva Refugee Convention is not generally applicable to war refugees , except for the specific reasons for fleeing listed below, which in some cases can also result from wars and civil wars. Refugee movements due to natural disasters and environmental changes are also outside the protection provided by the Convention.

Recognized refugees within the meaning of the Convention are those who are persecuted for

- race

- religion

- nationality

- Belonging to a certain social group

- political conviction

The aim of the convention is to achieve the most uniform possible legal status for people who no longer enjoy the protection of their home country. However, the original Geneva Refugee Convention contains a time limit: It only refers to persons who became refugees “as a result of events that occurred before January 1, 1951” (Art. 1 A No. 2). It thus does not contain any regulations for the rights of later refugees (this restriction was lifted in 1967 by the Additional Protocol).

On the one hand, the convention lists the duties of a refugee , in particular:

- Compliance with laws and regulations as well as the measures taken to maintain public order (Art. 2)

The convention also leads inter alia. the following rights of a refugee :

- Protection against discrimination based on race, religion or country of origin (Art. 3)

- Religious freedom (Art. 4) - whereby only the so-called requirement of equal treatment for residents applies here, d. H. Refugees and citizens are given equal religious freedom; Restrictions for citizens may then also apply to refugees.

- free access to the courts (Art. 16)

- Issuance of a travel document for refugees (Art. 28)

- Illegal entry is exempt from punishment, provided that the refugee reports to the authorities immediately and came directly from the country of refuge (Art. 31, Paragraph 1)

- Protection against expulsion (Art. 33, non-refoulement principle - principle of non-refoulement )

- Overall, the contracting states grant a refugee largely the same rights as foreigners in general; a refugee may therefore not be treated as a "second class foreigner".

Together with Art. 31 Para. 1, the principle of non-deportation according to Art. 33 Para. 1 is a central component of the agreement. According to this principle, a refugee is not “to be expelled or refused in any way across the borders of any area where his life or freedom would be threatened because of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political beliefs ". He may not be returned to a country without his refugee status having been clarified beforehand. In addition, according to Art. 31 Para. 1, a refugee who comes directly from an area in which his life or freedom was threatened within the meaning of Article 1 may not be punished for illegal entry or illegal residence, provided that he immediately agrees reported to the authorities ( ban on penalties ).

Article 33 contains the prohibition of refoulement with an exception in paragraph 2. Since the refoulement regulation in Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights is based on the absolute nature of the prohibition of torture, the practical relevance of Article 33 in Europe is very low.

The Convention allows States parties to make reservations on most of its articles. This is to ensure that a state that rejects an individual, possibly secondary provision of the convention can still accede to it and thus make a binding commitment to the other provisions.

On April 22, 1954, the convention came into force in the first six signatory states ( Australia , Belgium , Federal Republic of Germany , Denmark , Luxembourg , Norway ).

The 1967 Protocol on the Status of Refugees

The main point of criticism of the convention was that it was limited in time to reasons for fleeing that occurred before 1951. The contracting states could also limit themselves to granting only European refugees the corresponding rights. With the protocol on the legal status of refugees , any temporal and spatial restrictions have been lifted. The Geneva Refugee Convention now applies to states that have ratified both the Convention and the Protocol without restriction to all refugees, including those from states that have not ratified the Refugee Convention. The possibility of making reservations about individual articles of the Convention has also been reduced.

Problems and scope for interpretation

With regard to belonging to a social group, the convention does not explicitly state gender. More recently, especially since the publication of relevant UNHCR guidelines in 2002, the Geneva Convention has been interpreted in such a way that it also extends to gender-specific persecution .

Opinions differ on the question of whether the Geneva Refugee Convention also applies in extraterritorial areas - for example on the high seas and in the transit areas of airports. In 2006 the German Federal Government expressed the opinion that “according to predominant state practice” the principle of non-refoulement laid down in the GFK “only applies to territorial contact, ie at the border and in the interior of the country”; In 2008, she said: "The applicability of the Geneva Convention and outside the territory of the Contracting States, is controversial." In the case of Hirsi and Others v Italy ruled the European Court of Human Rights in 2012 that in Europe a protection on the high seas by the European Convention on Human Rights is given . In addition, the UNHCR, many national courts and large parts of legal research take the view that extraterritorial applicability does exist.

Adoption in European and national regulations

The Geneva Refugee Convention was incorporated into Directive 2011/95 / EU (Qualification Directive) and national laws - for example in Germany in Article 3 of the Asylum Procedure Act and today's Asylum Act ( Section 3 AsylG).

criticism

A research paper for the Australian government in 2000 summarized the problems of the agreement as follows:

- The agreement uses an outdated term refugee and sees a life in exile as the solution to the refugee problem.

- The agreement gives the refugees no right to assistance as long as they have not reached a country that is one of the signatories of the agreement. It neither obliges states not to evict and persecute their own citizens, nor does it contain burden-sharing obligations.

- The agreement does not take into account the social, societal and political impact of large numbers of asylum seekers on the host countries.

- The agreement promotes unequal treatment of refugees by giving preference to refugees who are mobile enough to reach signatory states over those who are in refugee camps outside.

- The expenditure of the Western countries for the screening and care of about 1.5 million asylum seekers in their national territory is many times what they would transfer to the UNHCR refugee agency for the care of about 22.3 million people in refugee camps.

- The agreement maintains the overly simple approach of seeing asylum seekers on the basis of their information either as political and thus “real” refugees or as refugees for economic reasons, although in most cases no real verification of the information of arriving refugees is possible.

UNHCR representatives see a need for a better distribution of the burden when dealing with refugees, but are not aiming for new negotiations on the legal status of refugees, as it is highly likely that this would not result in an improvement, but a deterioration in refugee protection.

New York Declaration

In 2016, the UN member states adopted the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants . In the non-binding declaration, the leaders of the 193 signatory countries pledged unanimously to work for 2018 global two pacts way: the " Global Compact refugees " ( english Global Compact for refugees ) and the " Global Compact to safe, orderly and legal migration "( English Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration ; short: Global Migration Pact). For example, the draft New York Declaration should address the human rights of migrants and the protection of particularly vulnerable migrants (including women and minors). and cooperation in border protection with respect for human rights is improved. Appropriate approaches were included in the New York Declaration. (For global compacts of the United Nations in general, see: Global Compact .)

In December 2017, the United States withdrew from the project because it was not compatible with Donald Trump's migration policy . They declared that the agreement would result in the loss of their state sovereignty on immigration issues. In April 2018, IOM Director William Lacy Swing expressed the expectation that the European Union would take a leading role in the negotiations on the migration pact.

See also

literature

- Sergo Mananashvili: Possibilities and limits of international and European law enforcement of the Geneva Refugee Convention . Nomos, Baden-Baden 2009, ISBN 978-3-8329-4833-7 .

- Seline Trevisanut: The Principle of Non-Refoulement at Sea and the Effectiveness of Asylum Protection . In: Armin von Bogdandy, Rüdiger Wolfrum, Christiane E. Philipp (Eds.): Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law . Volume 12 (2008), ISBN 978-90-04-16959-3 , pp. 205-246.

- The Refugee Convention at Fifty: A View from Forced Migration Studies , Ed .: Selm, Kamanga et al., Lexington 2003, ISBN 0-7391-0566-3

- Hathaway, James C .; Foster, Michelle (2014): The Law of Refugee Status: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511998300 .

Web links

- Australia, Belgium, Denmark, Federal Republic of Germany, Luxembourg, etc .: Final Act of the United Nations Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Status of Refugees and Stateless Persons. Held at Geneva from 2 July 1951 to 25 July 1951. - Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (with schedule). Signed at Geneva, on July 28, 1951. In: UNO , Volume 189 , 1954, I Treaties and international agreements, pp. 137-220 , no. 2545. Online in the United Nations Treaty Collection , in: United Nations Treaty Collection , UNTC (English; PDF document 5.32 MiB, PDF document 747 KiB, XHTML) including a data sheet with a list of participants (English, XHTML).

- FINAL ACT AND CONVENTION RELATING TO THE STATUS OF REFUGEES of the United Nations Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Status of Refugees and Stateless Persons. A / CONF.2 / 108 / Rev.1, November 26, 1952. United Nations Publications, Sales No .: 1951.Ⅳ.4. Online in the Official Documents System of the United Nations ( ODS ) (English and French; PDF document; 3.26 MiB; alternative URL ). - The document is a corrected version, the original version was published as A / CONF.2 / 108 in August 1951 (English and French; PDF document; 8.12 MiB; alternative URL ).

- Law on the Convention of 28 July 1951 on the Status of Refugees. From September 1, 1953 ( Federal Law Gazette 1953 II p. 559 ) - Law of the Federal Republic of Germany with the text of the agreement published below in English and French as well as a translation into German. The agreement itself was drawn up, signed and ratified in English and French; these two versions are therefore together the legally binding versions of the agreement.

- Wording of the Refugee Convention in the version currently valid for Switzerland

- Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees . [Including resolution 2198 (XXI) adopted by the United Nations General Assembly . With an introductory note from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees .] Published by: UNHCR Communications and Public Information Service. In: UNHCR (English; PDF file; 476 KiB).

- Convention on the Status of Refugees of July 28, 1951 (entered into force on April 22, 1954) - Protocol on the Status of Refugees of January 31, 1967 (entered into force on October 4, 1967) . Published by: The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Office of the Representative in the Federal Republic of Germany. In: UNHCR Representation for Germany, Berlin Office (PDF file; 211 KiB). - Refers to the federal German legislation on the agreement, which contains a translation into German, see web link above.

- The 1951 Refugee Convention. The Legislation that Underpins our Work. In: UNHCR (English, HTML).

- Questions and answers on the Geneva Refugee Convention ( memento of October 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) of the UNHCR

- Law on the Protocol of January 31, 1967 on the Status of Refugees. From 11 July 1969. ( Federal Law Gazette 1969 II p. 1293 ) - Law of the Federal Republic of Germany with the text of the protocol published below in English and French as well as a translation into German. The protocol itself was drawn up, signed and ratified in English and French; these two versions are therefore together the legally binding versions of the protocol.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Official Records of the General Assembly, Fifth Session, Supplement No. 20 (A / 1775), p.48.

- ^ United Nations Treaty Collection. Retrieved November 18, 2020 .

- ↑ Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees

- ↑ States Parties to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol , as of April 2011. Nauru joined the convention and the protocol in June 2011, see Nauru signs UN refugee convention

- ↑ Jakob Schönhagen: Ambivalent right. On the history of the Geneva Refugee Convention In: History of the Present , July 11, 2021, accessed on July 13, 2021

- ↑ Jamil Ddamulira Mujuzi: Rights of Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons in Africa . In: The African Regional Human Rights System . Ed .: Manisuli Ssenyonjo, Njihoff 2012, ISBN 978-9004-21814-7 , p. 177 ff.

- ↑ Jennifer Moore: Humanitarian Law in Action within Africa . Oxford University Press 2012, ISBN 978-0-19-985696-1 , pp. 158 f.

- ^ Gilbert Jaeger: Opening Keynote Address The Refugee Convention At Fifty . In: The Refugee Convention at Fifty: A View from Forced Migration Studies . Lexington 2003, ISBN 0-7391-0566-3 , p. 17.

- ↑ Peter Meier-Bergfeld: “The great mistake in the right of asylum” , Wiener Zeitung , December 23, 2008

- ↑ Cf. “50 Years of the Geneva Refugee Convention: 'We protect refugees, not economic migrants'. UN legal expert Buchhorn rejects the allegation of abuse - an interview ” , Tagesspiegel, July 27, 2001

- ↑ On the role of Art. 31 Para. 1 see: Andreas Fischer-Lescano , Johan Horst: The ban on penalization from Art. 31 I GFK. To justify criminal offenses when refugees enter the country . In: Journal for immigration law and immigration policy . ISSN 0721-5746 . 31st year, 2011, issue 3, pp. 81–90.

- ↑ International and human rights requirements for the deportation of refugees who have committed criminal offenses . Scientific service of the Bundestag. P. 10 f.

- ↑ Guidelines on international protection: Gender-specific persecution in connection with Article 1 A (2) of the 1951 Agreement and the 1967 Protocol on the Status of Refugees. (PDF; 163 kB) (No longer available online.) May 7, 2002, archived from the original on January 21, 2013 ; Retrieved May 19, 2013 .

- ↑ see e.g. B. Footnote 33 in: Friedrich Arndt: Orders in Transition: Global and Local Realities as Reflected in Transdisciplinary Analyzes . transcript Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-89942-783-7 , p. 310 ( google.com [accessed May 13, 2013]).

- ↑ see answer to question 10 in: Answer of the Federal Government to the minor question from MPs Josef Philip Winkler, Volker Beck (Cologne), Marieluise Beck (Bremen), other MPs and the Alliance 90 / THE GREENS parliamentary group ( Memento from November 1, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 110 kB), Drucksache 16/2723, September 25, 2006, p. 6. Also quoted in: Answer of the Federal Government to the Minor Question from Members Volker Beck (Cologne), Josef Philip Winkler, other members and the parliamentary group BÜNDNIS 90 / DIE GRÜNEN (PDF; 109 kB), printed matter 16/9204, May 15, 2008

- ↑ see answer to question 1. in: Answer of the federal government to the minor question from the members of parliament Volker Beck (Cologne), Josef Philip Winkler, another member of the parliament and the parliamentary group ALLIANCE 90 / THE GREENS (PDF; 109 kB), printed matter 16/9204, May 15, 2008, p. 5

- ↑ EU / Italy: Strengthening refugee protection on the high seas . Federal Agency for Civic Education, March 1, 2012, accessed March 18, 2018

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Refworld | Advisory Opinion on the Extraterritorial Application of Non-Refoulement Obligations under the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. Retrieved November 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Victor Pfaff: The legalization of immigration and asylum law demands the legal profession. In: Anwaltsblatt 2/2016. 2016, accessed December 2, 2016 . Pp. 82-86.

- ^ Adrienne Millbank: "The Problem with the 1951 Refugee Convention" Parliament of Australia, 2000

- ↑ Alexander Betts: "The Normative Terrain of the Global Refugee Regime" ethicsandinternationalaffairs.org of October 7, 2015

- ↑ "Has the Refugee Convention outlived its usefulness?" IRIN Johannesburg, March 26, 2012

- ↑ Kim Son Hoang: Scapegoat of the Geneva Refugee Convention. In: derstandard.at. July 28, 2016, accessed March 18, 2018 .

- ↑ The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration. In: 2030agenda.de. November 24, 2017. Retrieved May 28, 2018 .

- ^ Text of the draft declaration for the summit on 19 September. August 5, 2016, accessed on May 28, 2018 (English): “3.8 Effective protection of the human rights and fundamental freedoms of migrants, including women and children, regardless of their migratory status; the specific needs of migrants in vulnerable situations "

- ^ Text of the draft declaration for the summit on 19 September. August 5, 2016, accessed on May 28, 2018 (English): "3.9 International cooperation for border control with full respect for the human rights of migrants"

- ↑ See in particular the part “II. Commitments that apply to both refugees and migrants ". Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on September 19, 2016. New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants. In: A / RES / 71/1. August 5, 2016, accessed October 3, 2016 .

- ↑ Carlos Ballesteros: Trump Ignores Nikki Haley, Pulls US Out of Global Immigration Pact . Newsweek December 3, 2017, accessed April 12, 2018

- ^ Rex W. Tillerson : US Ends Participation in the Global Compact on Migration . In: geneva.usmission.gov , December 3, 2017, accessed April 7, 2018.

- ^ "A Critical Year for Unity in Defining Migration Policy Globally" IOM.int of April 4, 2018

- ↑ In the Federal Law Gazette Part II 1953, No. 19, published in Bonn on November 24, 1953 on pp. 559-589 announced. According to its Article 4, the law came into force on the day after its promulgation. The provisions of the Agreement - without prejudice to Article 43 of the Agreement on its entry into force - have acquired legal force for the Federal Republic of Germany one month after the promulgation of this Act, in accordance with Article 2 Paragraph 1 of the Act. According to its Article 43, the Agreement entered into force on April 22, 1954 between the Federal Republic of Germany, Australia (including the island of Norfolk, Naurau, New Guinea and Papua), Belgium, Denmark (including Greenland), Luxembourg and Norway. As required by Article 2 (2) of the Act, the date on which the Agreement entered into force pursuant to Article 43 of the Agreement was announced in the Federal Law Gazette. See: Notice of entry into force of the Convention of July 28, 1951 on the Status of Refugees. From May 25, 1954. ( Federal Law Gazette 1954 II p. 619 ) Current entry on the Agreement on the Legal Status of Refugees in the Legal Information System for the Federal Republic of Germany .

- ↑ In the Federal Law Gazette Part II 1969, No. 46, issued in Bonn on July 17, 1969 on pp. 1293–1297 announced. According to its Article 3, the law came into force on the day after its promulgation. According to Article VIII, Paragraph 2, the Protocol entered into force for the Federal Republic of Germany on November 5, 1969, the date on which the German instrument of accession was deposited. As required by Article 3 Paragraph 2 of the Act, the date on which the Agreement entered into force for the Federal Republic of Germany under Article VIII Paragraph 2 was announced in the Federal Law Gazette. See: Notice of entry into force of the Protocol on the Status of Refugees. From April 14, 1970. ( Federal Law Gazette 1970 II p. 194 ) Current entry in the protocol on the legal status of refugees in the legal information system for the Federal Republic of Germany .