Refugee status

Refugee status is a legal status that is formally granted to an asylum seeker in Germany if, as a non-German citizen, he is outside his country of origin because of a well-founded fear of persecution because of his race, religion, nationality, political convictions or membership of a certain social group as his national does not receive protection there or does not want to take advantage of protection there for fear or cannot or does not want to return there as a stateless person ( Section 3 (1) Asylum Act (AsylG); Section 3 (4) AsylG). In the Federal Republic of Germany, the existence of refugee status is determined by the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) in an asylum procedure , possibly in addition to the right to asylum according to Art. 16a GG . In legal proceedings, the BAMF can also be obliged by a court to recognize an applicant as a refugee ( Section 113 (5 ) VwGO ). According to § 6 AsylG, the decision of the Federal Office on the existence of refugee status, apart from the extradition procedure and the procedure according to § 58a of the Residence Act (AufenthG), is binding in all matters in which the granting of refugee status is legally relevant.

Establishing that a person has refugee status is a declaratory act. According to the Geneva Refugee Convention (GRC), one does not become a refugee by officially granting refugee status, but by fulfilling the criteria specified in the GRC. In German law, the BAMF - or in legal proceedings, the factual court - therefore only determines whether the applicant actually falls under the definition of refugee or not, based on the facts described by the applicant in the asylum procedure and other material on the applicant's country of origin. For the further stay in the federal territory, e.g. the issue of a residence permit according to § 25 Abs. 2 Alt. 1 AufenthG, this positive statement is necessary. The legal consequences of granting refugee status thus occur ex nunc . It is therefore possible that a person is staying in federal territory who actually falls under the definition of a refugee because he or she fulfills the requirements specified in Article 1 A No. 2 of the GFK, but no further rights from this, such as a right to a residence permit or a Can assert a travel document for refugees because, in the absence of an application, no determination of refugee status has yet been made.

History of origin

The term refugee is defined internationally in Art. 1 A No. 2 of the Geneva Refugee Convention (GFK) of 1951. According to this, a refugee is anyone who is outside of the country of which he is a national of which he is a national and cannot claim the protection of this country because of his well-founded fear of persecution because of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a certain social group or because of his political convictions or does not want to make use of these because of these fears, or who is a stateless person as a result of such events outside the country in which he was habitually resident and does not want to return there.

The requirements of the GFK are specified in Germany by the Qualification Directive of the European Parliament and the Council, which was enacted in 2004 and revised in 2011. This determines, among other things:

- the actors of whom persecution i. S. d. CSF (Article 6),

- the actors who can offer protection from persecution (Article 7),

- acts of persecution (Article 9),

- the reasons for persecution (Article 10),

- the applicant's duty to cooperate and the member state's duty to review (Article 4), internal protection (Article 8),

- loss of refugee status (Article 11), exclusion from recognition (Article 12) and

- issuing residence permits and travel documents to recognized refugees (Articles 24 and 25).

The provisions of the directive were incorporated into German asylum law by the law implementing Directive 2011/95 / EU of August 28, 2013, which came into force on December 1, 2013. In some cases, the provisions of the directive under Union law have been taken over word for word, which avoids national scope for interpretation. Furthermore, the Federal Office and the courts can now use the directive.

When asked whether the applicant is threatened with a well-founded fear of persecution, the German asylum case law uses the prognostic standard of considerable probability . The fear of persecution is justified if, when considering the overall circumstances of the individual case, the circumstances in which persecution can be assumed outweigh the reasons which speak against persecution.

Implementation in Germany

The Federal Republic of Germany acceded to the Convention on the Status of Refugees on December 9, 1953 and the 1967 Protocol on November 5, 1969. Through the Approval Act of September 1, 1953 (Federal Law Gazette II 1953, p. 559), the agreement is binding for German sovereign power and, according to Article 59 (2) of the Basic Law, has the rank of a federal law. On January 10, 1953, the so-called Asylum Ordinance, which regulated the asylum procedure in the Federal Republic of Germany for the first time, came into force. Section 5 of this ordinance stipulates that persons are recognized as refugees if they fall under the definition of Article 1 A of the GRC.

Legal situation until 2005

The Aliens Act (AuslG), which came into force on October 1, 1965, replaced the ordinance of 1953 and provided rules for the determination, revocation, for further residence as well as for the legal status and binding nature of the decision. Furthermore, § 14 AuslG 1965 already provided that, in application of the non-refoulement requirement of Article 33 of the GRC, people were not allowed to be deported to a state in which they would be exposed to the dangers specified there. For the first time, an explicit distinction was also made between the recognition of refugees under the GRC, which was limited to European refugees and events before January 1, 1951, and the right to asylum under the Basic Law until the 1967 Protocol came into force.

In the years that followed, German asylum law focused on determining the right to asylum under the Basic Law. The Aliens Act of 1990 reinstated a uniform procedure for determining refugee status according to the GFK, after this was abolished in 1982 with the separation of the regulations on the asylum procedure from the Aliens Act and the creation of the Asylum Procedure Act in favor of the right to asylum under the Basic Law. However, the procedure was not carried out on the basis of Art. 1 A No. 2 GFK; On the contrary, Sections 51 and 53 of the Aliens Act enabled persons who met the requirements of Section 51 (1) AuslG - which revived the non-refoulement requirement of Article 33 GFK and, according to the case law of the Federal Administrative Court , essentially an abbreviated reproduction of Art. 1 A No. 2 GFK and should therefore be applied as if it were in line with the concept of refugee in the GFK - it does not grant a status of its own under aliens law, but only grants protection against deportation under aliens law. The fact that persons for whom the requirements of Section 51 (1) AuslG have been definitively established are refugees within the meaning of the GFK was only regulated by Section 3 AsylG. This read in its version at the time:

"A foreigner is a refugee within the meaning of the Agreement on the Legal Status of Refugees if the Federal Office or a court has established incontestably that in the state of which he is a national or in which he has his habitual residence as a stateless person, the conditions set out in § 51 of the Aliens Act. "

Persons for whom the prerequisites of Section 51 (1) AuslG have been definitively established were generally entitled to a residence permit (Section 70 (1) AsylVfG old version) and subsequently to a travel document for refugees . In contrast to those entitled to asylum according to Art. 16a GG, who according to § 68 AsylVfG a. F. received an unlimited residence permit after the final recognition, the residence permit was limited to a maximum of two years. It was only after eight years that it was possible to obtain an unlimited right of residence via Section 35 AuslG.

Immigration Act and Qualification Directive

With the entry into force of the Immigration Act on January 1, 2005, the legal status of persons who meet the requirements of the now new Section 60, Subsection 1 of the Residence Act (AufenthG), which, in contrast to its predecessor, Section 51, Subsection 1, AuslG, was again explicitly referred to the GRC accepted, fulfilled, adapted to that of those entitled to asylum according to the Basic Law. As a result of the recognition, both groups of people received a three-year residence permit , after three years a settlement permit was possible in accordance with Section 26 subs. 3 AufenthG. Likewise, the requirements for easier family reunification, equality in work permit law, equality in the area of social benefits and obtaining “family asylum” have been expanded to include people who meet the requirements of Section 60 (1) Residence Act. Contrary to the proposal of the UNHCR , however, a more detailed definition of a refugee was not adopted in German law and the legal status of Section 60 (1) AufenthG as a “ban on deportation” was retained.

The Immigration Act also made it clear that persecution within the meaning of the GFK can also be carried out by non-state actors. In contrast to other contracting states, this was not previously the case in Germany, as the Federal Administrative Court, in its case law on Section 51 (1) AuslG, took the view that the persecution must be carried out by the state (or at least be attributed to it). Furthermore, gender-specific persecution was explicitly classified as relevant to asylum.

Even before the Immigration Act came into force, the Council of the European Union had passed Directive 2004/83 / EC (the so-called Qualification Directive), which aimed to introduce common criteria for the recognition of asylum seekers as refugees within the meaning of Article 1 of the Geneva Convention. The aim of the directive was also to curb the secondary migration of asylum seekers between Member States, insofar as it is based solely on different legal provisions, by approximating the legal provisions for the recognition and content of refugee status and subsidiary protection.

The directive was transposed into national law through the law for the implementation of residence and asylum directives of the European Union of August 19, 2007 (Federal Law Gazette I, p. 1970). For the first time, based on Article 13 of the Directive, the independent status of refugee status was created in German law. § 3 AsylG has been reformulated. According to Section 3 (4) AsylG, a foreigner who is a refugee according to Section 3 (1) AsylG was granted refugee status.

New version of the qualification guideline

The new version of the Qualification Directive (Directive 2011/95 / EU) once again resulted in some legal changes in German refugee law. Through the law to implement the directive of August 28, 2013 (Federal Law Gazette I, p. 3474.), in force since December 1, 2013, the legislature removed the requirements for granting refugee status from the scope of the Residence Act and added them instead in the Asylum Procedure Act . Section 3 AsylG now contains on the basis of Art. 1 A No. 2 GFK and Art. 2 lit. d Directive 2011/95 / EU the definition of a refugee as well as the reasons for exclusion that lead to the refusal of refugee status. Sections 3a to 3e AsylG now also regulate the requirements for granting refugee status based on Directive 2011/95 / EU. The principle of the ban on deportation, anchored in Section 60 (1) of the Residence Act, was retained as a legal consequence of refugee status.

Furthermore, the so-called deportation bans under European law (formerly: Section 60 subs. 2, 3 and 7 sentence 2 AufenthG old version) have now been adopted in Section 4 AsylG , thereby creating the legal status of subsidiary protected . Together with refugee recognition, the two components now form what is known as “international protection”. The national prohibitions on deportation in accordance with Section 60 (5) and (7) sentence 1 of the Residence Act were retained.

Differences between entitlement to asylum and refugee status

Refugee status and entitlement to asylum are not the same. Those who are entitled to asylum will at the same time have refugee status; but the reverse is not always the case.

The entitlement to asylum is based on the classic triad of a flight fate:

- Persecution in the home country in a manner relevant to asylum by government agencies,

- therefore escape to Germany,

- therefore filing an asylum application in Germany.

If only one of these characteristics is missing, asylum is not considered. Asylum is also out of the question if the asylum seeker entered Germany from a safe country of origin ( Section 29a AsylG in conjunction with Annex II of the Act) or via a safe third country ( Section 26a AsylG) or entered Germany without contact is not proven to a safe third country. This very limited concept of persecution does not cover many persecution fates at all. To be mentioned are in particular

- persecution by non-state actors (e.g. in countries in which state structures have been largely destroyed, e.g. currently in Somalia ),

- leaving the home country without a current threat,

- Missing causality in the three characteristics (e.g. flight to Germany only after safe admission in a third country or very late application for asylum after entry) and

- Above all, the so-called reasons for after- flight , i.e. circumstances that only occurred during the stay in the country of refuge (e.g. change of government in the home country while the person concerned is already in Germany, or oppositional activity developed for the first time in Germany).

However, these cases are usually included in the term refugee.

The application of the Dublin procedure according to Regulation (EU) No. 604/2013 (Dublin III) extends to all forms of international protection (entitlement to asylum, refugee status, subsidiary protection).

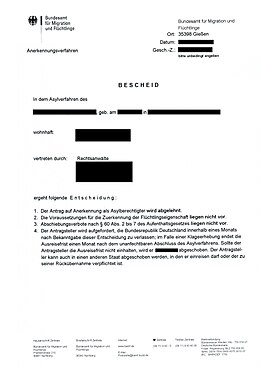

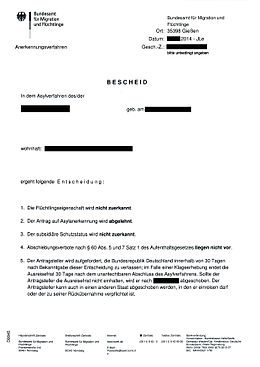

Recognition procedure

In the recognition procedure before the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees , it is determined with each asylum application whether the refugee status exists. However, it is possible that the applicant restricts his application to international protection from the outset ( Section 13 (2) AsylG). If the prerequisites of Art. 16a GG are met, the Federal Office tenors in its decision “ The applicant is recognized as entitled to asylum. ". If the requirements of Section 3 (1) AsylG are met, the Federal Office tenors: “ The applicant will be granted refugee status. ". If only the prerequisites for subsidiary protection (§ 4 AsylG) are met, the Federal Office tenors “ The applicant is granted subsidiary protection status. ". If there is a ban on deportation, the existence of the respective prerequisite is determined, stating the exact legal basis ( Section 31 (2) and (3) AsylG).

Consequences of the granting of refugee status in terms of residence law

The granting of refugee status creates a legal entitlement to a residence permit ( Section 25, Subsection 2, Alternative 1 of the Residence Act). This must initially be granted for three years ( Section 26 subs. 1 sentence 2 of the Residence Act). Within these three years, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees is obliged, in accordance with Section 73 (2a) AsylG, to check whether the requirements for revoking refugee status are met. If the prerequisites are met, the Federal Office must notify the immigration authorities at the latest within one month after the decision in favor of the beneficiary has not been contested for three years. Otherwise there is no need to notify the immigration authorities. Persons who have been granted refugee status are generally entitled to a travel document for refugees in accordance with Article 28, Paragraph 1, Clause 1 of the GFK, provided they are lawfully staying in federal territory. The residence permit according to § 25 Abs. 2 Alternative 1 AufenthG establishes such a stay.

If there is no such notification, the recognized refugee is entitled to a settlement permit after five years if he meets the further requirements of Section 26 subs. 3 sentence 1 of the Residence Act. The period is reduced to three years if the refugee speaks German. This is the case if he can demonstrate language skills at level C1 of the Common European Framework of Reference . For children who entered Germany before the age of 18, Section 35 of the Residence Act can be applied accordingly. It is also possible to obtain a permanent EU residence permit after a total of five years .

The spouses and unmarried minor children of persons who have been granted refugee status can, under the conditions of Section 26 Paragraphs 1 and 2 in conjunction with V. m. Paragraph 5 AsylG can also be recognized as refugees. This also applies to the parents of a minor unmarried refugee and his minor unmarried siblings (Section 26, Paragraph 3 in conjunction with Paragraph 5 of the Asylum Act). In addition, Section 29 (2) and Section 30 (1) of the Residence Act provide for easier family reunification .

In contrast to most residence permits, the so-called rule granting requirements of Section 5, Paragraphs 1 and 2 of the Residence Act are irrelevant . The residence permit can, however, be refused in individual cases if the recognized refugee is to be regarded as a threat to the security of the Federal Republic of Germany for serious reasons.

For holders of a residence permit according to § 25 Abs. 2 Alt. 1 AufenthG, no residence requirement may be imposed solely on the basis of receiving social benefits. In 2008, the Federal Administrative Court declared the previous practice to be unlawful, as it is not compatible with Article 23 of the GFK. However, through the Integration Act, the legislature decided via Section 12a of the Residence Act to introduce a residence requirement to promote sustainable integration into the living conditions of the Federal Republic of Germany . According to this, all persons who were recognized as refugees after January 1, 2016, are obliged to take their habitual residence (domicile) in the country in which they are to carry out their residence for a maximum of three years from the date of recognition or issuance of the residence permit Asylum procedure or as part of their admission procedure.

Holders of a travel document issued in accordance with Article 28 of the GFK also have the option of being naturalized with the acceptance of multiple nationalities ( Section 12 (1) No. 6 StAG). Furthermore, it is possible within the scope of the discretionary naturalization according to § 8 StAG to be naturalized after six, instead of eight years of residence.

Web links

- Directive 2011/95 / EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of December 13, 2011 on standards for the recognition of third-country nationals or stateless persons as persons entitled to international protection, for a uniform status for refugees or for persons with the right to subsidiary protection and for the content of the protection to be granted

- Information from the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees on the different forms of recognition in the asylum procedure

Individual evidence

- ↑ UNHCR, Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , 1979, No. 28 and Recital No. 21 of Directive 2011/95 / EU. Even Federal Administrative Court judgment of 13 February 2014 to 1 C 13/04 , para. 15th

- ↑ According to Section 25 (2) AufenthG, only those who have been granted refugee status by the Federal Office are entitled to a residence permit.

- ↑ Hailbronner: AuslR, § 3a AsylVfG, Rn. 2 (86th update, as of June 2014).

- ↑ Hailbronner: AuslR, § 3 AsylVfG, Rn. 7 (86th update, as of June 2014).

- ↑ Hailbronner: AuslR, § 3 AsylVfG, Rn. 8 (86th update, as of June 2014).

- ↑ See BVerfG, decision of December 8, 2014 - 2 BvR 450/11 , Rn. 35 mwN

- ↑ BGBl. I 1953 p. 3

- ^ Aliens Act of April 28, 1965 , Section Four: Asylum Law

- ↑ On the historical development: Tiedemann, ZAR 2009, 161 .

- ↑ Tiedemann, ZAR 2009, 161 <164f.> .

- ↑ Stefan Richter: Self-created reasons for after-flight and the legal status of convention refugees according to the case law of the Federal Constitutional Court on the fundamental right to asylum and the law on the revision of the law on foreigners in ZAR , 1991, 1 (36).

- ↑ BVerwG, ruling v. January 21, 1992 - 1 C 21.87, BVerwGE 89, 296.

- ↑ a b UNHCR, Statement on the Immigration Act of January 14, 2002 ( Memento of the original of March 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , P. 4

- ↑ § 3 AsylG in the version up to December 31, 2004.

- ↑ a b BVwerG, ruling v. March 17, 2004 - 1 C 1.03, BVerwGE 120, 206. A residence permit according to § 70 Abs. 1 AsylVfG a. F. establishes a legal residence within the meaning of Article 28, Paragraph 1, Clause 1 of the GFK.

- ↑ § 34 AuslG ( Memento of the original from January 3, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. in the version up to December 31, 2004.

- ↑ § 35 AuslG ( Memento of the original from January 3, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. in the version up to December 31, 2004.

- ↑ BVerwG, judgment of January 18, 1994 - 9 C 48.92, BVerwGE 95, 42.

- ↑ Julia Duchrow: Refugee Law and Immigration Law, taking into account the so-called Qualification Guideline in the Journal for Immigration Law and Foreign Policy , 2004, 339 <340>.

- ↑ Julia Duchrow: Refugee Law and Immigration Law, taking into account the so-called Qualification Guideline in the Journal for Aliens Law and Aliens Policy , 2004, p. 340

- ↑ Recital 17 of Directive 2004/83 / EC (PDF)

- ↑ Recital 7 of the directive

- ↑ The Member States recognize a third-country national or a stateless person who meets the requirements of Chapters II and III as refugee status.

- ↑ § 3 AsylG in the version from August 28, 2007.

- ↑ Section 2 Grant of Protection, Subsection 2: International Protection

- ↑ BVerwG, judgment 1 C 8.11 of May 22, 2012, cf. also Advocate General at the ECJ, September 11, 2014 - C-373/13

- ↑ BVerwG, judgment of January 15, 2008 - 1 C 17.07 , Rn. 12ff.

- ↑ Section 8.1.3.1 Preliminary application information from the Federal Ministry of the Interior regarding the Nationality Act in the version of the Act on the Implementation of Residence and Asylum Directives of the European Union of August 19, 2007; also no. 8.1.3.1 of the General Administrative Regulation on Nationality Law (StAR-VwV) of December 13, 2000