al-Andalus

al-Andalus ( Arabic الأندلس, Zentralatlas-Tamazight ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ Andalus ) is the Arabic name for the parts of the Iberian Peninsula that were ruled by Muslims between 711 and 1492 . Under constitutional law, al-Andalus was successively a province of the Umayyad (711-750) or Abbasid (750-756) caliphate founded by Caliph Al-Walid I , the emirate of Córdoba (756-929), the caliphate of Córdoba ( 929-1031), a group of " Taifa " - (successor) kingdoms and a province in the realms of the North African Berber dynasties of the Almoravids and then the Almohads; eventually it fell again into Taifa kingdoms. For long periods, especially during the time of the Caliphate of Cordoba , al-Andalus was a center of learning. Cordoba became a leading cultural and economic center of both the Mediterranean and the Islamic world.

As early as the early 8th century, al-Andalus was in conflict with the Christian kingdoms in the north, which were attempting the military reconquest of Spain as part of the Reconquista . In 1085 Alfonso VI conquered . from Castile Toledo , with which a gradual descent from al-Andalus began. After all, after the fall of Cordoba in 1236, the emirate of Granada remained as the last Muslim-dominated area in present-day Spain. The Portuguese Reconquista ended with the conquest of the Algarve by Alfonso III. 1249/1250. Granada was in 1238 to that of Ferdinand III. ruled the kingdom of Castile paying tribute . Eventually the last emir handed over to Muhammad XII. January 2, 1492 Granada to Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile , Los Reyes Católicos (the "Catholic Kings"), with which the Muslim rule on the Iberian Peninsula came to an end.

Etymology of al-Andalus

The etymology of the word "al-Andalus" is controversial. As a name for the Iberian Peninsula or its Muslim-ruled part, the word is first documented by coin inscriptions of the Muslim conquerors around 715.

Proponents of traditional theory derive the name from the name of the Vandals , the Germanic tribe that established a short-lived empire in Iberia from 409 to 429. However, there is no source evidence for this, and it does not seem credible that the name is said to have survived for almost three centuries until the arrival of the Arabs in 711. The hypothesis is sometimes traced back to Reinhart Dozy , a 19th century orientalist, but Dozy found it and already recognized some of its weaknesses. Although he assumed that "al-Andalus" developed from "Vandale", he believed that the name only referred geographically to the - unknown - port from which the Vandals left Iberia for Africa.

The Islamic scholar Heinz Halm also suspected a Germanic origin of the name. According to him, al-Andalus is the old gothica sors ( lat. "The lot of the Goths "). From this he reconstructs a Gothic landa-hlauts , whose initial <l> is analogous to Alexandria ( al-Iskandariyya ), Lombardy ( al-Ankubardiyya ), Alicante (Latin Leucante , Arabic al-Laqant or Madinat Laqant ) etc. by the Arabs as part of the article al was misinterpreted. The Romanist Georg Bossong contradicted this with arguments relating to place names , historical and linguistic structures. He thinks that the name comes from pre-Roman times, because the name Andaluz is used for several places in mountainous parts of Castile. Furthermore, the morpheme and- in Spanish place names is not uncommon, and the morpheme -luz occurs several times throughout Spain. Bossong further suspects, following similar considerations by Dozy and Halm, that the name was originally that of a small island off the city of Tarifa , the place where the first advance detachment set foot on Hispanic soil in July 710, which is also the southernmost point of the Iberian Peninsula . This name would then have been carried over to the Baetica region and ultimately to Moorish Spain as a whole.

Bossong's thesis is countered, however, that the place names with -andaluz in the name also come from the Middle Ages and may have been derived from al-Andalus. In the course of the Repoblación, it was not uncommon for Christian Andalusians to settle in the border areas. The Romanist Volker Noll also contradicted Halms' thesis and put forward considerations that returned to the vandal hypothesis.

story

Conquest and early years

The invading army of 711 consisted of Arabs and (probably mostly) North African Berbers .

On the orders of the Umayyad caliph al-Walid I , Tariq ibn Ziyad first led a small troop of warriors to Iberia, who landed in Gibraltar on April 30, 711 (see also Islamic expansion ). Tariq ibn Ziyad was able to achieve a victory over the Visigoth army under King Roderich in the battle of the Río Guadalete (July 19 to 26, 711) , which proved to be decisive for the further course of the conflict. He then brought most of the Iberian Peninsula under Muslim control in a seven-year campaign. Then the Muslim troops finally crossed the Pyrenees and occupied parts of southern France . In 732 they were defeated by the Franks under Karl Martell in the battle of Tours .

This made the Iberian Peninsula, under the name of al-Andalus, part of the Umayyad Empire, which reached the height of its expansion. However, the rebellion of the noble Visigoth Pelayo began as early as 718 in a remote mountain region of Asturias , which led to the founding of the initially very small Christian kingdom of Asturias .

At first al-Andalus was ruled by governors appointed by the caliph, whose rule lasted mostly less than three years. However, a series of armed conflicts between various Muslim groups led to the caliphs losing their control. Yusuf al-Fihri , aided by the weakness of the Umayyad caliphs, was able to assert himself as the main winner of these disputes and became a de facto independent ruler.

The emirate and caliphate of Cordoba

In 750 the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyads and took control of the Arab Empire . However, the Umayyad prince Abd ar-Rahman I (later called ad-Dāchil ), who was expelled by the Abbasids, was able to overthrow Yusuf al-Fihri as ruler of al-Andalus and rise to become the emir of Córdoba , who was independent of the Abbasids . In thirty years of reign he established fragile control over large parts of al-Andalus against the opposition of the al-Fihri family and the partisans of the Abbasid caliphs.

For the next 150 years he and his descendants were emirs of Córdoba and nominally ruled over al-Andalus and at times also parts of western North Africa. But the extent of their actual rule fluctuated and always depended, especially in the Marches on the border with the Christians, on the abilities of the respective emir. In 900 , the power of Emir Abdallah did not extend beyond Córdoba. His grandson and successor, Abd ar-Rahman III. but was able to restore the power of the Umayyads in all of al-Andalus from 912 onwards and also expand it to parts of the Maghreb . In 929 he proclaimed himself caliph and brought his empire into competition with both the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad and the Fatimid caliph in Ifrīqiya , with whom he wrestled for control of the Maghreb.

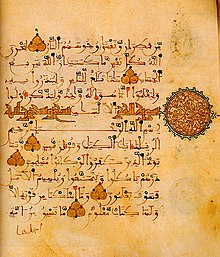

The period of the caliphate is considered by Muslim authors to be the golden age of al-Andalus. With arable farming using artificial irrigation systems and food imported from the Middle East , the agricultural sector supplied Córdoba and other cities far better than the economy in other areas of Europe. Under the Caliphate, Cordoba eventually became the largest and most prosperous city in Europe, ahead of Constantinople, with a population of perhaps 500,000 . Cordoba was one of the leading cultural centers in the Islamic world. The works of its most important philosophers and scholars, Albucasis and Averroes in particular , had a significant influence on the intellectual development of medieval Europe, and the libraries and universities of al-Andalus were famous and prestigious in Europe and the Islamic world. After the conquest of Toledo in 1085, scholars from other countries came there to translate scientific literature from Arabic into Latin. The most famous of these was Michael Scotus (around 1175 - around 1235), who later brought the works of Averroes and Avicenna to Italy . This transfer of knowledge had a strong influence on the development of scholasticism in Christian Europe.

The first Taifa period

The rule of the Caliphate of Cordoba collapsed in a ruinous civil war that lasted from 1009 to 1013. In 1031 the caliphate was finally formally abolished. Al-Andalus broke up into several essentially independent states called Taifas . These were mostly too weak to defend themselves against the constant attacks and demands for tribute of the Christian states in the north and west. These so-called Galician peoples by the Muslims had spread from their original bases in Galicia , Asturias , Cantabria , the Basque Country and the Franconian Spanish Mark and became the kingdoms of Navarre , León , Portugal , Castile and Aragon and the county of Barcelona . Their attacks on the territories of the Taifa kings assumed increasingly threatening proportions. After the conquest of Toledo by Alfonso VI. of Castile and León in 1085 the Abbadid ruler al-Muʿtamid, who was ruled by Alfonso VI. was strong in distress, contact with other Taifa kings and organized a delegation to the Almoravids Rulers Yusuf ibn Tashfin to for support against Alfonso VI him. to ask. Yusuf ibn Tashfin, who shortly before had conquered Morocco at high speed , crossed the Strait of Gibraltar in the same year and inflicted a heavy defeat on the Christians in the battle of Zallaqa . This move was also directed against the Taifa kings themselves, when the Almoravids conquered their kingdoms after defeating Alfonso VI. of Castile did not show unity.

Almoravids, Almohads and Merinids

With the exception of Saragossa, Yusuf ibn Tashfin deposed all Muslim princes in Iberia by 1094 and annexed their territories. He also recaptured Valencia from the Christians. In the 12th century followed the Almoraviden Almohad , another Berber - Dynasty after Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur the Castilian King Alfonso VIII. In 1195 in the Battle of Alarcos defeated. In 1212, however, the Almohads were subject to an alliance of the Christian kingdoms under the leadership of Alfonso VIII of Castile in the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa . The Almohads ruled al-Andalus for another decade, but were only a reflection of earlier power and importance, and the internal unrest after the death of Yusuf II. Al-Mustansir led to the early re-establishment of the Taifas . The Taifas, again independent but still weak, were soon conquered by Portugal , Castile and Aragon . After the fall of Murcia (1243) and the Algarve (1249), the only Muslim-ruled area was the emirate of Granada , which became a tribute to Castile. This tribute was paid mainly in gold , which was brought to Iberia via the trade routes in the Sahara from what is now Mali and Burkina Faso .

The last serious threat to the Christian kingdoms of Iberia was the rise of the Merinids in Morocco in the 13th and 14th centuries. Century. They viewed Granada as part of their sphere of influence and occupied some of its cities, including Algeciras . However, they were unable to conquer Tarifa , which in 1340 until the arrival of a Castilian army under Alfonso XI. endured. With the support of Alfonso IV of Portugal and Peter IV of Aragon , Alfonso XI defeated. the Merinids were decisive in the battle of the Salado in 1340 and took Algeciras in 1344. Gibraltar , at that time under the rule of Granada, was besieged from 1349-1350 until Alfonso XI. there, with a large part of his army, was taken away by the Black Death . His successor Peter I of Castile made peace with the Muslims and directed his ambitions to Christian areas. The wars and rebellions between and in the Christian territories during the following 150 years initially ensured the continued existence of Muslim Granada.

The emirate of Granada

For the 150 years following the peace treaty with King Peter I of Castile , Granada continued to exist as a Muslim emirate under the Nasrid dynasty , which guaranteed the Christian residents of its area freedom of worship. Arabic continued to be its official language and the mother tongue of the majority of its residents. The emirate connected the trade routes of Europe with those of the Maghreb and thus brokered trade relations with the Muslim world, especially in the gold trade with the areas south of the Sahara.

The marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile in 1469 paved the way for the final attack on the rest of Muslim Iberia, a carefully planned and financed campaign. The royal couple also got the Pope to declare their campaign a crusade , which Granada was finally defeated in January 1492 when the last emir Muhammad XII. Abu Abdallah , called Boabdil , had to surrender to them in his fortress, the Alhambra . The last Muslim rule in Iberia had thus fallen and the Reconquista was completed.

society

Al-Andalus society was composed mainly of three religious groups: Christians, Muslims and Jews. The Muslims in turn were divided into several ethnic groups, the largest of which were the Arabs and the Berbers. As Mozarabs Christians were called who had culturally part of the Muslim dominance assimilated, yet their Christian faith had maintained with its rituals and its Romance languages such as by acquisition of Arab customs, Arab art and Arabic expressions. It was customary for the various groups to have their own quarters in the cities of al-Andalus.

The Berbers, who had made the bulk of the Muslim invaders, lived mainly in the mountainous regions of what is now northern Portugal and in the Meseta , the Castilian highlands, while the Arabs settled in the south and in the Ebro Valley in the northeast. Since the Caliphate of Cordoba, a professional army has been maintained by making greater use of the so-called Saqāliba . These were mainly owed to the ruler and hardly useful for power struggles. However, they were difficult to integrate into the population because they were not rooted in the country. When the peninsula was conquered, the land of the original owners was not sold, but remained in their possession unless they had fled, which was the case with many Visigoth nobles. These possessions were given to Muslims who had proven themselves on military expeditions, which resulted in many of them becoming landowners. After the fall of the caliphate, the partial kingdoms and their leaders were composed of three ethnic groups: the North African Berbers, the Saqāliba and the Andalusians, by which one now understood all Muslims of Arab and Iberian origin, including the broad stratum of new converts ( muwalladūn ).

Towards the end of the 15th century, around 50,000 Jews lived in Granada and roughly 100,000 in all of Muslim-ruled Iberia, some of whom occupied economically or socially important positions, for example as tax collectors, traders or doctors and diplomats.

Christians and Jews

Non-Muslims were part of the ahl al Dhimma ( subjects under protection). Accordingly, they had to pay the jizya . The (“pagan”) population of al-Andalus, which did not belong to any scriptural religion , was counted as a Majus . The treatment of religious minorities under the Caliphate is a controversial topic in research and in public. There is also no consensus on the usefulness of using modern terms such as tolerance and equality in relation to Andalusian society. There are differences of opinion in research as to the actual extent to which Jews and Christians are tolerated by Muslims.

The historian and literary scholar Darío Fernández-Morera sees in his essay The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise the assumption of a tolerant, pluralistic and multicultural al-Andalus as a modern myth that has already established itself in the academic mainstream, but in no way of historical reality correspond. His theses, which he deepened in his book of the same name from 2016, have also met with opposition.

The Romanist and Medievalist María Rosa Menocal believes that "tolerance was an inherent aspect of the society of al-Andalus". For them, the situation of the Jews under the caliphate was much better than in the Christian empires of Europe. For example, Jews immigrated from other parts of Europe because they promised themselves a comparatively better position in al-Andalus. (The same applied to members of Christian sects who were considered heretics in Christian states .) In al-Andalus, one of the most stable and prosperous Jewish communities developed during the Middle Ages , forming a center of Jewish culture that produced eminent scholars.

Bernard Lewis , on the other hand, points out that in al-Andalus, as in other parts of the Islamic world, there could be no question of equal rights for people of different faiths, since this is not provided for in Islamic law . The Spanish mediavist Francisco García Fitz comes to a similar conclusion, who describes “tolerance in Islamic Spain” as a “ multicultural myth”: “It is indisputable that there have been cultural borrowings and influences and peaceful economic relationships, but not relationships based on equality and full acceptance of the differences. ”The Spanish literary scholar Darío Fernández-Morera comes to the conclusion in his essay The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise that the relationship between the three religious groups was shaped by religious, political and racial conflicts, which in the best of times could only be brought under control through the tyrannical assertiveness of the rulers. Catholics have suffered from repressive measures such as high taxation, confiscation of their goods and slavery and religious persecution. Muhammad I (823-886) ordered the destruction of all 711 new churches built since the conquest of Spain (see also Martyrs of Córdoba 851-859) and his successors only rarely approved the construction of new churches or the repair of existing ones. The Muslim jurist Ibn Abdun advocated segregation of Muslims from Christian and Jewish dhimmis . Relations between Christian and Jewish subjects were also marked by mutual resentment.

The treatment of non-Muslims in al-Andalus varied at different times. The longest period of relative tolerance began in 912 under Abd ar-Rahman III. and his son al-Hakam II . The Jews of al-Andalus prospered in the Caliphate of Córdoba and made their contribution to the prosperity of the country in science, trade and industry, for example in the trade in silk and slaves (→ Radhanites ). During this time, southern Iberia was asylum for oppressed Jews from other countries. Even during such periods of tolerance, individual Christians propagated martyrdom . In the 9th century, 48 Christians were executed in Cordoba for religious offenses against Islam. They are known as the " Martyrs of Cordoba ". These zealots occasionally found imitators.

After the death of al-Hakam II in 976, the situation of non-Muslims worsened. For example, a pogrom against Jews in Cordoba is reported in 1011. The first major persecution took place on December 30, 1066, the massacre of Granada , in which 1,500 families were killed (see also Ziriden von Granada - Jews ). In the early 12th century, the Catholic residents of Málaga and Granada were expelled to Morocco. There may have been interim persecution of the Jews under the Almoravids and Almohads , but the sources do not give a clear picture. In any case, the situation of non-Muslims seems to have worsened after 1160.

Against the background of these repetitive waves of violence against non-Muslims, especially against Jews, many Jewish, but also Muslim scholars left Muslim Iberia and went to Toledo , which was then still relatively tolerant and which the Christians had conquered in 1085. Some Jews - it is believed up to 40,000 - joined the Christian armies, while others joined the Almoravids in their fight against Alfonso VI. of Castile .

The Almohads took power in 1147 in the areas of the Maghreb and Iberia previously controlled by the Almoravids. Their worldview was far more fundamentalist than that of the Almoravids, and accordingly the dhimmis were treated much harsher under their rule. Otherwise faced with the choice between conversion and death, many Christians and Jews left the country. Some, such as Maimonides ' family , fled east to more tolerant Muslim areas, while others emigrated to the expanding Christian kingdoms. At the same time, however, the Almohads promoted science and art, especially the Falsafah (Philosophers) School , to which Ibn Tufail , Ibn al-Arabi and Averroes belonged.

In medieval Iberia, Muslims and Christians found themselves in an almost uninterrupted war that shaped the history of Spain and Portugal at that time. Periodic raids from al-Andalus devastated the Christian kingdoms, bringing back booty and slaves . For example, the Almohad caliph Yaʿqūb al-Mansūr took 3,000 women and children as slaves during his attack on Lisbon in 1189, and the governor of Córdoba, who was subordinate to him, took 3,000 Christians as slaves during the attack on Silves in 1191 .

List of governors of al-Andalus

- 712-714 Musa ibn Nusayr

- 714-716 Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa

- 716 Ayub ibn Habib al-Lachmi

- 716-719 al-Hurr ibn Abd ar-Rahman

- 719-721 as-Samh ibn Malik al-Chawlani

- 721 Abd ar-Rahman ibn Abd Allah al-Ghafiqi

- 721-726 Anbasa ibn Suhaym al-Kalbi

- 726 Udhra ibn Abd Allah al-Fihri

- 726-728 Yahya ibn Sallama al-Kalbi

- 728 Hudhaifa ibn al-Ahwas al-Ashja'i

- 728-729 Uthman ibn Abi Nas'a al-Chath'ami

- 729-730 al-Haitham ibn 'Ubaid al-Kanani

- 730 Muhammad ibn Abd Allah al-Ashja'i

- 730-732 Abd ar-Rahman ibn Abd Allah al-Ghafiqi (2nd time)

- 732-734 Abd al-Malik ibn Qatan al-Fihri

- 734-740 Uqba ibn Hajjaj al-Saluli

- 740–742 Abd al-Malik ibn Qatan al-Fihri (2nd time)

- 742 Baldsch ibn Bischr

- 742-743 Tha'laba ibn Salama al-'Amili

- 743-745 Abu l-Khattar Husam ibn Darar al-Kalbi

- 745-746 Thawaba ibn Salama al-Jadhami

- 746-747 Abd al-Rahman ibn Kabir al-Lahmi

- 747-756 Yusuf ibn Abd ar-Rahman al-Fihri

The successor Abd ar-Rahman I rose to be the first emir of Córdoba and thus separated Andalusia from the Abbasid caliphate.

reception

In 1997, a network of roads in Spain was designated a cultural route by the Council of Europe . It was named "The Legacy of al-Andalus".

literature

sources

- Kenneth Baxter Wolf: Conquerors and Chroniclers of Early Medieval Spain. Translated Texts for Historians . Liverpool University Press, Liverpool 1999, pp. 111-161. English translation of the Mozarabic Chronicle with commentary; Attention: Different chapter counting of chap. 59-69, pp. 134-138.

- Wilhelm Hoenerbach (Ed.): Islamic History of Spain: Translation of the Aʻmāl al-a'lām and additional texts. Artemis, Zurich / Stuttgart 1970

Secondary literature

- Sylvia Alphéus, Lothar Jegensdorf: Love transforms the desert into a fragrant flower garden. Love poems from the Arab era in Spain. Romeon, Jüchen 2020. ISBN 978-3-96229-203-4 .

- Georg Bossong : Moorish Spain: History and Culture. 3rd Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-55488-9 .

- Brian A. Catlos: Kingdoms of Faith. A New History of Islamic Spain. Basic Books, New York 2018 (German: al-Andalus: History of Islamic Spain. Munich 2019).

- André Clot : Moorish Spain: 800 years of high Islamic culture in Al Andalus. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-491-96116-5 .

- Roger Collins : The Arab Conquest of Spain, 710-797, A History of Spain. Blackwell, Oxford et al. 2000, ISBN 0-631-19405-3 .

- Christian Ewert, Almut von Gladiss , Karl-Heinz Golzio: Hispania Antiqua. Monuments of Islam: from the beginnings to the 12th century. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-1855-3 .

- Darío Fernández-Morera: The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise . In: The Intercollegiate Review , 2006, pp. 23–31 ( online , PDF, 189 kB)

- Pierre Guichard: Al-Andalus. Eight centuries of Muslim civilization in Spain. Wasmuth, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-8030-4028-0 .

- Ulrich Haarmann, Heinz Halm (ed.): History of the Arab world. 4th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-47486-1 .

- Wilhelm Hoenerbach: Poetic comparisons of the Andalusian Arabs Ibn-al-Kattānī, Abū-ʿAbdallāh Muḥammad Ibn-al-Ḥasan. Oriental seminar at the University of Bonn , Bonn 1973

- Arnold Hottinger : The Moors: Arab Culture in Spain. Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zurich 1995, 3rd edition 1997, reprint of the 3rd edition. Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-7705-3075-6 .

- Salma Khadra Jayyusi (Ed.): The legacy of Muslim Spain. Handbook of Oriental Studies, Dept. 1. The Near and Middle East. 2 volumes. Brill, Leiden 1992, ISBN 90-04-09952-2 , ISBN 90-04-09953-0 (standard work).

- Chris Lowney: A Vanished World: Muslims, Christians and Jews in Medieval Spain. Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford (et al.) 2006, ISBN 0-19-531191-4 .

- Stephen O'Shea: Sea of Faith: Islam and Christianity in the Medieval Mediterranean World. Walker, New York 2006, ISBN 0-8027-1498-6 .

- Alfred Schlicht: The Arabs and Europe. 2000 years of shared history. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-17-019906-4 .

- Johannes Thomas : Al-Andalus: Historiography and Archeology . In: Markus Groß , Karl-Heinz Ohlig (ed.): The emergence of a world religion IV - Mohammed - history or myth? (= Inârah. 8). Hans Schiler, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-89930-100-7 .

- Al-Andalus: where three worlds met. In: The UNESCO -Courier , December 1991 ( online , PDF, 8.97 MB)

Web links

- UNESCO culture: The Routes of al-Andalus: spiritual convergence and intercultural dialogue , April 7, 2001

- Literature about Al Andalus in the catalog of the Ibero-American Institute in Berlin

Remarks

- ↑ Andalus, al-. In: John L. Esposito (Ed.): Oxford Dictionary of Islam . Oxford University Press. 2003. Oxford Reference Online. Accessed June 12, 2006.

- ↑ The dating uncertainty arises from the fact that the coins are inscribed in both Latin and Arabic and the year of minting differs in the two languages. The oldest evidence of this Arabic name is a dinar coin that is kept in the Archaeological Museum of Madrid. The coin bears “al-Andalus” in Arabic script on one side and the Iberian-Latin “Span” on the other side. Heinz Halm: Al-Andalus and Gothica Sors. In: Islam. No. 66, 1989, pp. 252-263, doi: 10.1515 / islm.1989.66.2.252 .

- ↑ a b c Georg Bossong: The name Al-Andalus: New considerations on an old problem. In: David Restle, Dietmar Zaefferer (Ed.): Sounds and systems: studies in structure and change. A festschrift for Theo Vennemann. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin 2002, pp. 149-164. ( online , PDF, 1 MB)

- ↑ Reinhart P. Dozy: Recherches sur l'histoire et la littérature des Arabes d'Espagne pendant le Moyen-Age. 1881.

- ^ Heinz Halm: Al-Andalus and Gothica Sors. In: Der Islam , 1989, No. 66, pp. 252–263, doi: 10.1515 / islm.1989.66.2.252 , based on the formulation of Hydatius ("Vandali cognomine Silingi Baeticam sortiuntur"), reproduced by Isidore of Seville (" Wandali autem Silingi Baeticam sortiuntur ”).

- ↑ The village of Andaluz ( 41 ° 31 ′ N , 2 ° 49 ′ W ) is located at the foot of the Andaluz Mountain on the Duero River in the Soria province , and the villages of Torreandaluz and Centenera de Andaluz are within 10 km.

- ^ Noll, Volker: Notes on Spanish toponymy: Andalucía , in: Günter Holtus / Johannes Kramer / Wolfgang Schweickard (ed.), Italica et Romanica. Festschrift for Max Pfister on his 65th birthday. III. Tübingen, Niemeyer, 1997, pp. 199-210 ( online , PDF, 188 kB).

- ^ Tertius Chandler: Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census. St. David's University Press, 1987 ( Populations of Largest Cities in PMNs from 2000 BC to 1988 AD ( Memento of December 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive )). ISBN 0-88946-207-0 .

- ↑ Ibn Khaldun : al-Muqaddima

- ↑ See E. Lévi-Provençal: Art. "Al-Muʿtamid ibn ʿAbbād. 1. Life" in The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition Vol. VII, pp. 766-767. Here p. 767a.

- ^ David J. Wasserstein: Jewish élites in Al-Andalus. In: Daniel Frank (Ed.): The Jews of Medieval Islam: Community, Society and Identity. Brill, 1995, ISBN 90-04-10404-6 , p. 101.

- ^ S. Mikel De Epalza: Mozarabs. In: Jayyusi 1992, pp. 149–170, here pp. 153 ff.

- ↑ The Ornament of the World by María Rosa Menocal ( Memento of November 9, 2005 in the Internet Archive ), accessed June 12, 2006

- ↑ Bernard W. Lewis: The Jews of Islam. 1984, p. 4.

- ↑ Francisco Garcia Fitz: "On the way to the Jihad" , DIE WELT, June 1, 2006

- ↑ Darío Fernández-Morera: The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise . In: The Intercollegiate Review , 2006, pp. 23–31 (30) ( online , PDF, 189 kB)

- ↑ a b Darío Fernández-Morera (2006), p. 24

- ↑ a b c Darío Fernández-Morera, 2006, p. 29

- ↑ Darío Fernández-Morera (2006), p. 26f.

- ^ Ilan Stavans : The Scroll and the Cross: 1,000 Years of Jewish-Hispanic Literature. Routledge, London 2003, ISBN 0-415-92930-X , p. 10.

- ↑ Joel Kraemer: Moses Maimonides: An Intellectual Portrait. In: Kenneth Seeskin (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to Maimonides. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2005, ISBN 0-521-81974-1 , pp. 10-13.

- ^ Orthodox Europe: St Eulogius and the Blessing of Cordoba . Archived from the original on January 13, 2009. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- ↑ Frederick M. Schweitzer, Marvin Perry: Anti-Semitism: myth and hate from antiquity to the present. Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, ISBN 0-312-16561-7 , pp. 267-268 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Christiane Harzig, Dirk Hoerder, Adrian Shubert: The Historical Practice in Diversity. Berghahn Books, 2003, ISBN 1-57181-377-2 , p. 42.

- ^ Richard Gottheil, Meyer Kayserling : Granada. In: Isidore Singer (Ed.): Jewish Encyclopedia . Funk and Wagnalls, New York 1901–1906 ..

- ^ Joseph F. O'Callaghan: A History of Medieval Spain. Cornell University Press, 1975, ISBN 0-8014-9264-5 , p. 286.

- ^ Norman Roth: Jews, Visigoths and Muslims in Medieval Spain: Cooperation and Conflict. Brill, Leiden 1994, ISBN 90-04-06131-2 , pp. 113-116.

- ↑ Almohads. (2015). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from http://www. britica.com/topic/Almohads

- ^ A b Daniel H. Frank, Oliver Leaman: The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Jewish Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-521-65574-9 , pp. 137-138.

- ↑ Sephardim

- ↑ Joel Kraemer: Moses Maimonides: An Intellectual Portrait. In: Kenneth Seeskin (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to Maimonides. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2005, ISBN 0-521-81974-1 , pp. 16-17.

- ↑ ransoming captives in Crusader Spain: The Order of Merced on the Christian-Islamic Frontier.

- ↑ Las Rutas de El legado andalusi: Homepage of the cultural route