Mozarabic Chronicle

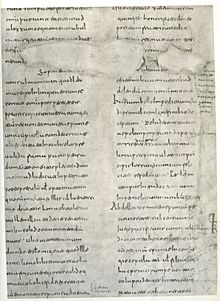

Mozarabic Chronicle is a modern term for an anonymously transmitted Latin medieval chronicle . It was written in 754 by a Christian author who was a cleric and lived in al-Andalus , the Muslim-ruled part of the Iberian Peninsula . The Christians then living under Muslim rule are called Mozarabs ; The present name of the chronicle is derived from this term. Its value as a source for a time with relatively few sources is estimated very highly by modern research. It is considered the most reliable narrative source for the final phase of the Visigoth Empire and describes its destruction in the course of the Islamic expansion . It is also the oldest source describing the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula.

Names and research history

The work used to be known under other names. The first editor, Bishop Prudencio de Sandoval , who edited the chronicle in 1615, called it Historia de Isidoro obispo de Badajoz ("History of Bishop Isidore of Badajoz "). He held a bishop of Pax Iulia named Isidor ( Isidorus Pacensis ) for the author and identified Pax Iulia with Badajoz. This was a double error; Isidore is not the author, nor is Badajoz the ancient Pax Iulia. Isidorus Pacensis is rather a fictional figure that came about through a medieval spelling mistake; originally meant the bishop and historian Isidore of Seville ( Isidorus Hispalensis ). However, this cannot be the author, as he lived in the 7th century. The alleged chronicler Isidorus Pacensis was also called Isidorus the Younger ( Isidorus Junior ) in the early modern period to distinguish it from Isidor of Seville .

In 1885 Jules Tailhan published a new edition of the Chronicle in Paris. It was clear to him that the traditionally assumed authorship of Bishop Isidore is a mistake. Therefore, he called the author Anonyme de Cordoue ("Anonymous of Córdoba"), because he thought it was probably a resident of Córdoba . Theodor Mommsen , who edited the chronicle in 1894, called it Continuatio Isidoriana Hispana (" Hispanic continuation [of the chronicle] Isidore [of Seville]"). The editor Juan Gil introduced the name Chronica Muzarabica in 1973 ; Another editor, José Eduardo López Pereira, called the work in his 1980 edition "Mozarabic Chronicle of 754".

Author and content

The Mozarabic Chronicle follows on from various late antique chronicles and deals with the period from the accession of Emperor Herakleios to 754. The events in Hispania and al-Andalus are the focus, but the chronicler also goes into the history of the Byzantine Empire and the Caliphate. Although there are errors in the description, the reliability increases as the chronicler approaches his own time. He provides valuable information, especially for the circumstances of the Arab conquest, which he describes as a catastrophe, and for the period that followed. The chronicler judges the Arab rulers, both the governors of al-Andalus and the caliphs in Damascus , without religious prejudice, according to their merits or wrongdoings, and gives some of them high praise. He avoids entering into the religious opposition between Christians and Muslims or expressing himself about Islam, and does not name the Muslims as such, but uses ethnic expressions to describe them as Arabs, Moors or Saracens . He accuses one of the Arab governors of al-Andalus, Yahya ibn Sallama al-Kalbi (726–728), whom he criticizes as a terrible and cruel ruler, of having returned goods to Christians that had been stolen from them after the Muslim invasion . He presumably saw this measure as a threat to inner peace.

Nothing is known about the author except that he was a Christian and in all probability a clergyman. He apparently had access to information from oral or written Arabic sources and perhaps also worked for the Arab administration. Córdoba, Toledo and Murcia are considered as his place of residence ; a stay in Córdoba can be inferred indirectly from his own words. His good knowledge of late antique and early medieval literature points to a first-rate cultural center like Toledo. He used different systems for dating, including the one with the year 38 BC. The beginning of the “Spanish era ”, the Islamic era and the years of government of the Byzantine emperors and caliphs. He claims to have also written a more detailed historical work, which he calls epitoma ("demolition"); it was about the turmoil of the civil war in al-Andalus in the forties of the 8th century and has not been preserved.

Another 8th century chronicle known as the Chronicle of 741 or Chronica Byzantia-Arabica treats Hispania marginally and is primarily devoted to events in the eastern Mediterranean. But it was created on the Iberian Peninsula, since the chronicler dates from the Spanish era. The earlier held view that this work was known to the author of the Mozarabic Chronicle and was used by him has proven to be incorrect.

The author of the Mozarabic Chronicle depicts the fall of the Visigoth Empire in a completely different way than the chronicle of the Christian Kingdom of Asturias , which began in the 9th century and which shaped medieval and early modern historiography in Spain. The legends placed in the foreground by the Asturian chroniclers, according to which the Visigoth king Witiza was one of the main culprits in the decline and fall of the Visigoth Empire and Witiza's sons cooperated with the attacking Muslims and thus contributed significantly to the Visigothic defeat, do not appear in the depiction of Mozarab, rather, he judges Witiza's government positively. His description has contributed significantly to the fact that modern research was able to expose the treachery legend.

Linguistically, the work by the Mozarabic chronicler, written in very vulgar Latin, is one of the most difficult Latin texts of the early Middle Ages. It is thus also a testimony to the decline in the knowledge of the Latin language among educated Mozarabs of the 8th century.

Medieval historians who used the Mozarabic Chronicle include Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Musa ar-Razi (10th century), the unknown author of the Historia Pseudo-Isidoriana (12th century) and Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada .

Editions and translations

- Juan Gil (Ed.): Chronica Hispana saeculi VIII et IX (= Corpus Christianorum . Continuatio Mediaevalis , Vol. 65). Brepols, Turnhout 2018, ISBN 978-2-503-57481-3 , pp. 325–382 (critical edition)

- José Eduardo López Pereira (Ed.): Crónica Mozárabe de 754 , Zaragoza 1980, ISBN 84-7013-166-4 (Latin text and Spanish translation)

- Kenneth Baxter Wolf (Ed.): Conquerors and Chroniclers of Early Medieval Spain , 2nd Edition, Translated Texts for Historians . Liverpool University Press, Liverpool 1999, ISBN 0-85323-554-6 , pp. 25–42 (introduction), 111–160 (English translation)

- Continuatio Isidoriana Hispana a. DCCLIV . In: Theodor Mommsen (Ed.): Auctores antiquissimi 11: Chronica minora saec. IV. V. VI. VII. (II). Berlin 1894, pp. 323–369 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

literature

- Carmen Cardelle de Hartmann : The textual transmission of the Mozarabic Chronicle of 754 . In: Early Medieval Europe Vol. 8, 1999, pp. 13-29, doi: 10.1111 / 1468-0254.00037

- Ana María Moure Casas: En torno a las fuentes de la Crónica Mozárabe . In: Humanitas. In honorem Antonio Fontán . Gredos, Madrid 1992, ISBN 84-249-1489-9 , pp. 351-363

Remarks

- ↑ Ann Christys: The History of Ibn Habib and ethnogenesis in al-Andalus , in: Richard Corradini, Maximilianhabenberger, Helmut Reimitz (eds.): The Construction of Communities in the Early Middle Ages: The Transformation of the Roman World 12, p 323-348, 2003, p. 325 ( academia.edu ).

- ↑ Wolf (1999) pp. 32-42.

- ^ Mozarabic Chronicle 75 (edition by López Pereira) or 61 (edition by Gil); see Wolf (1999) p. 35.

- ↑ Wolf (1999) p. 26f.

- ↑ On this question, see Cardelle de Hartmann (1999) pp. 17–19; Wolf (1999) p. 26 and note 6; Roger Collins : The Arab Conquest of Spain 710-797 , Oxford 1994, pp. 57-59.

- ^ Mozarabic Chronicles 86 and 88 (edition by López Pereira) and 70 and 72 (edition by Gil). See Cardelle de Hartmann (1999) p. 17 and note 20, Collins (1994) p. 59.

- ↑ See also the fundamental work by Dietrich Claude : Investigations on the fall of the Visigoth Empire (711-725). In: Historisches Jahrbuch Vol. 108, 1988, pp. 329–358, here: 334f., 340–351.

- ↑ Cardelle de Hartmann (1999) pp. 25-29.