Political and Social History of Islam

The history of Islam ( Arabic تاريخ الإسلام, DMG tārīḫ al-Islām ) is presented in this article from a political, cultural and social historical perspective. Due to the long historical development and the geographical extent of the Islamic world, only the main features can be presented here. To make the overview easier, a breakdown is made on the one hand by time epochs, on the other hand, a western ( Maghreb ) and an eastern part ( Maschrek ) are distinguished within the Dār al-Islam . In order not to let the list of individual proofs become too long, reference is also made to the corresponding main articles.

Historical overview

Spread and first flowering period

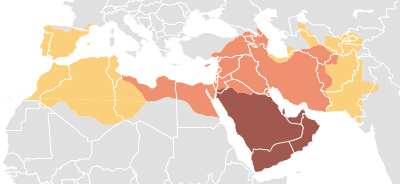

Starting from the Islamic “original community” in Arabia, Islam had already spread over a large part of the then known world in the first two centuries of its existence. In the course of its more than 1,300-year history, different beliefs, societies and states developed within the Islamic world. The appropriation and transformation of the culture of antiquity led to an early heyday of Islamic culture , which radiated into Christian Europe. The dominance and integrating power of the Islamic religion and the Arabic language common to all educated people were decisive for this development . Until the rise of modern natural science in the wake of the European Enlightenment , the influence of Islamic scientists, especially doctors , remained unbroken in Europe as well.

differentiation

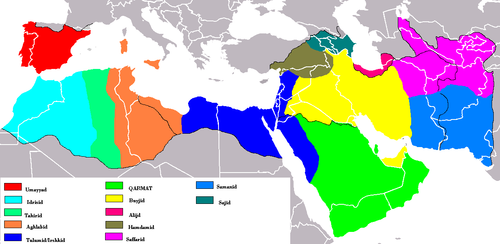

As a result of the separation of Sunnis and Shiites , the religious unity of the Islamic world was lost with the end of the Umayyad dynasty and the establishment of the Emirate of Córdoba . The individual regions remained closely linked through trade and migration, but developed their own cultural traditions under changing ruling dynasties. The Mongol storm of the 13th and the devastating epidemics of the 14th century led to profound changes in the political situation.

During the 11th – 15th In the 19th century, areas with Arabic as the everyday and cultural language separated from those in which Persian became the most important language in secular culture and Arabic remained the language of religious and legal discourse. In large parts of the eastern Islamic world, the Turks became the ruling elite. The Abbasid caliphate continued until Baghdad was destroyed in the Mongolian storm in 1258, but the Arabic-speaking area was divided into three politically separate regions: Iraq, mostly united under one rule with Iran (" Both Iraq "), Egypt as supremacy over Syria and that western Arabia, as well as the areas of the Maghreb .

Although the Islamic rulers, the caliphs , retained their role as regional rulers for a certain time, in Baghdad, Cairo or in al-Andalus , and the office of the caliph could still serve to legitimize the exercise of Islamic rule, the real power went to sultans , emirs , Maliks and other rulers over. In the 11th-18th In the 19th century, Islam spread deep into India, western China, and across the oceans to East Africa, the coastal areas of South Asia, Southeast Asia and South China. Such an expansion, in its cultural and political diversity, makes central rule and coordinated administration impossible. In the further spread of Islam, the traders and the Sufi mystics of the Tarīqa played just as important a role as an army or an administrative head before.

Early modern empires

In the 15th and 16th centuries, three new great powers emerged with the Safavid dynasty , the Mughal Empire and the Ottoman Empire . In the course of their self-assurance and guided by the need for appropriate cultural representation of their new political role, Islamic culture experienced another heyday in these countries. Supported by the rulers, guided by court manufacturers under the protection of the rulers, masterpieces of art and buildings were created that are now part of the world cultural heritage .

At the beginning of the 12th century, trade between Europe and the Islamic world, especially with the Ottoman Empire, grew strongly. As early as the 15th century, an export-oriented economic structure had emerged in Asia Minor. The increasing European demand for commercial goods such as spices, oriental carpets , glass and ceramic goods destroyed traditional handicrafts in the Islamic countries as a result of mass production and the use of cheaper materials. At the same time, the abundant silver in Europe due to imports from South America weakened the silver- based economy of its most important trading partner. The revolution in military technology that followed with the introduction of firearms in the 16th century put a strain on the state finances of the great empires.

Colonialism and independence

With the development of the modern world order, the primacy of Islamic culture was lost: the Western European Renaissance, Reformation and the beginning of the scientific and industrial revolution were almost unnoticed by the Islamic world. The political and economic dominance of Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries led to a self-interested policy of colonialism towards the countries of the Islamic world and their division into spheres of interest of the respective colonial powers, for example in the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1907) . With the support of major European powers, the Pahlavi dynasty was established in Iran in 1925 . Since the conquest of the Mughal Empire by Great Britain (1858) India was under direct British rule as a crown colony , and Egypt was a British protectorate since 1882 . Afghanistan , originally part of the Mughal Empire, has been the scene of armed conflicts on the border between the British and Russian spheres of influence since the late 19th century, and in the 20th century the Cold War and the American War on Terror .

Numerous reform movements developed in the Islamic countries at the time of European colonial rule and in the process of dealing with it, among which a modernist and a traditionalist-fundamentalist school of thought can be distinguished. Founded in the 19th and early 20th centuries, several of these organizations are still of ideological and political importance today.

The pursuit of independence, for example in the Greek Revolution (1821–1829) or in the Ottoman-Saudi War (1811–1818) led to territorial losses of the Ottoman Empire, which perished in the Turkish Liberation War in 1923 . India was in 1947 on the basis of Nations two-theory in today's Indian state and the Muslim countries of Pakistan and Bangladesh split . Indonesia declared its independence from the Dutch colonial power in 1945 . In the Islamic West, the states of the Maghreb only gained their independence in the middle of the 20th century, for example in the Algerian War . In 1979, the Iranian monarchy was overthrown in the Islamic Revolution . The country has been an Islamic republic since then . In the east, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, independent, partly autocratic states emerged.

Modern

The hegemony of modern Western culture represents a fundamental challenge for the Islamic world. The discussion ultimately focuses on the question of the extent to which Muslims today should adopt Western liberal achievements and political concepts, or whether the Islamic world has the means on the one hand, and whether on the other it would even have a duty to create its own Islamic modernity. In contrast to the short-lived Arab Spring , there is a fundamentalist position that economic and cultural decline is a result of disregarding God's commandments. In this case, it is argued, only an uncompromising return to Scripture and the traditions of the Prophet can solve the dilemma.

The idea of the Islamic Awakening since the 1970s stands for a return to Islamic values and traditions in a conscious departure from Western customs. Particularly in the context of poverty and a lack of access to education, Islamist terrorism is gaining ground and is directed not only against the western-secular, but also against the society of its own or neighboring countries. Civil wars, for example in Syria , devastate some of the oldest and most important cities of Islamic culture and thus part of the material and cultural heritage of Islam in the core countries of its origin.

Islamic historiography

Early Islamic historians

· az-Zubair (634 / 35–712 / 13)

· Ibn Ishaq (d. 761)

· al-Waqidi (745–822)

· Ibn Hisham (d. 834)

· ibn Saʿd (d. 845)

· Ibn 'Abd al-Hakam (d. 871)

· ibn Shabba (d. 877)

· at-Tabarī (839–923)

· al-Mas'udi (d. 956 or 946)

· Ibn ʿAsākir (d. 1176)

· Ibn al-Athīr (d. 1233)

· Ibn Chaldūn (1332–1406)

· al-Maqrizi (d. 1442)

· al-ʿAsqalānī (1372–1449)

The transmission of the history of Islam began soon after the death of Muhammad. Tales of the Prophet, his companions, and the early days of Islam have been compiled from various sources; Methods had to be developed to assess their reliability. The Hadith Science ( Arabic علم الحديث, DMG ilm al-ḥadīth ) comprises a number of disciplines on which the study of the sayings of Muhammad, the hadith , is based. Jalal ad-Din as-Suyūtī described the principles according to which the authenticity of a chain of narration ( Isnād ) is assessed. The term " ʿIlm ar-ridschāl " denotes the biographical science, the aim of which is to assess the reliability of the information transmitted by a person.

The at-Tabarī (839-923), who worked in Baghdad, is the best-known author in the field of universal or imperial history with his annalistic Ta'rīch / Achbār ar-rusul wal-mulūk (story / news of the ambassadors and kings). At-Tabarī sees himself as a narrator who should contain his own conclusions and explanations.

The first detailed studies on the methodological criticism of historiography and the philosophy of history appeared in the works of the politician and historian Ibn Chaldūn (1332-1406), especially in the Muqaddima (introduction) to the Kitāb al-ʿIbar ("Book of Hints", actually "World History") ). He regards the past as strange and in need of interpretation; when looking at a bygone age, the relevant historical material must be judged according to certain principles. Often it has happened that a historian has copied uncritically from previous authors without worrying about whether the respective tradition fits into the overall picture of an epoch or with other information transmitted by a person. He understands the historiography he has called for as a completely new method and repeatedly describes it as a "new science".

6-10 century

Arabia before Islam

Muslims refer to the time before Islam as Jāhiliyya , the epoch of "ignorance". Islam has its origin in the Arabian Peninsula ( Arabic الجزيرة العربية jasirat al-ʿarabiya , DMG al-jazīra al-ʿarabiyya 'Island of the Arabs '), asteppe and desert areamainly inhabited by Bedouins . At that time, Arabia was not a politically and socially uniform community, but lay on the edge of the sphere of influence of the Byzantine Empire on the one hand and the Persian Empire on the other, as well as their vassal states, the Ghassanids affiliated to the Byzantinesand the Lachmids allied with the Persians.

Mecca , the homeland of Muhammad , had developed into a trading metropolis due to its favorable location on the Incense Route that ran from southern Arabia to Syria, which was dominated by the Koreishites , an Arab tribe of merchants, who also included Muhammad's clan, the Hashemites , belonged to.

Although also numerous Jews (especially in Mecca and the nearby at-Ta'if, Yathrib (there, for example, the tribes of the Banu Qainuqa , Banū n-Nadīr and Banu Quraiza ), Wadi l-Qura, Chaibar , Fatal and Taima) and Christians lived on the Arabian Peninsula, according to Islamic tradition, the majority of the inhabitants professed a variety of pagan tribal gods, such as al-Lat , Manat and al-Uzza . The local deity Hubal was worshiped in Mecca . The Kaaba - arab. also baytu llāh , d. H. "House of God" - in Mecca was already an important place of pilgrimage in pre-Islamic times and represented a source of economic, religious and political influence for the Koreishites. Information about ancient Arabic deities was obtained from Hišām b. Muḥammad b. as-Sāʾib al-Kalbī, known as Ibn al-Kalbī (d. 819–821) reported.

as-Sīra an-Nabawīya - The biography of the prophets

The earliest known biography of the prophet ( Arabic السيرة النبوية, DMG as-sīra an-nabawīya ) is Ibn Ishāqs Sirat Rasul Allah ("The Life of the Messenger of God"). It is quoted in excerpts in later works and arrangements by Ibn Hisham and at-Tabari .

The Prophet Mohammed was born in Mecca around 570 . At the age of about forty (609) Mohammed first had visions in the cave of Hira. The archangel Gabriel (Ĝibrīl) commanded him to write down the word of God ( Allah ). At first he only shared his experience with a small circle of confidants, but soon gained followers. When they began to fight the old polytheistic religion, there was a break between Mohammed and the Koreishites. In 620 Mohammed and his followers submitted to the protection of the two Medinan tribes, the Aus and Khasradsch , who were looking for a mediator (Arabic: hakam ). In September 622, Mohammed and his followers moved from Mecca to Yathrib ( Medina ), an event that, as Hejra, marked the beginning of the Islamic calendar .

The move to Medina also marked the beginning of Muhammad's political activity. He had the respected position of a mediator in Medinan society and was also regarded as the head of the Islamic community ( Umma ). Islam experienced its first social form in Medina. The Medinan suras of the Koran make more reference to concrete regulations of the life and organization of the Islamic community. Mohammed led several campaigns against Mecca since 623 (victory of the Muslims in the battle of Badr (624), the battle of Uhud (625) and the battle of the trenches (627)) until an armistice was concluded in March 628. In 629, the Muslims began the pilgrimage to Mecca ( Hajj ) for the first time . In 630 the leaders of Mecca handed over the city to Mohammed, who then had the pagan idols removed from the Kaaba .

In the years before Muhammad's death in 632, the influence of Islam spread to the entire Arabian Peninsula. Contracts were concluded with the tribal leaders , some of which contained a tribute obligation , and some included the recognition of Muhammad as a prophet. The community order of Medina , handed down in Ibn Hisham's adaptation of Ibn Ishāq's biography of the prophet, is a contract that Mohammed concluded in 622 between the emigrants from Mecca and his helpers in Yathrib, later Medina . It defines a number of rights and duties and thus created the basis for the community concept of the ummah .

When Mohammed died in Medina on June 8, 632, he did not leave a male heir. His only daughter was Fatima .

The Era of the Righteous Caliphs (632-661)

The term "rightly guided caliphs" ( Arabic الخلفاء الراشدون, DMG al-ḫulafāʾ ar-rāšidūn ) refers to the Sunni view of the first four caliphs , who between 632 and 661 led the ummah , the community of believers, before its split. The four successors are Abdallah Abū Bakr (r. 632–634), ʿUmar ibn al-Chattāb (r. 634–644), ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān , (r. 644–655) and ʿAlī ibn Abī Tālib (r. 656–661 ). During these thirty years, Islam continued to expand, and at the same time disputes about the succession arose, which ultimately led to the division of Islam into Sunnah and Shia .

The Ridda Wars fall during the brief reign of Abū Bakr . The caliphate ʿUmar ibn al-Chattābs marks decisive victories over the Byzantine Empire and the Persian Sassanids and thus the expansion of Islam to Syria and Palestine ( Bilad al-Sham ), Egypt , parts of Mesopotamia and Iran . The decisive factor for the rapid conquest of the former Byzantine and Persian territories was not only the motivation and mobility of the Arab troops, but above all the fact that Byzantium and Persia were exhausted by the long and bloody Roman-Persian wars that had only ended in 628/29 . The Arab conquerors then profited considerably from the already existing higher cultural development in the former Byzantine areas and in Persia; Likewise, the effective Byzantine and Persian administrative practice was largely adopted or adapted.

The most important cultural achievement of ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffāns was the final and still authoritative editing of the Koran , some twenty years after the death of the Prophet Mohammed. Around 651 the first wave of Islamic expansion came to a standstill in the west in Cyrenaica (Libya) and in the east on Amu Darya (northern Persia, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan). Asia Minor remained under Byzantine rule until the 11th century.

The election of ʿAlī ibn Abī Tālib led to an open discussion on the question of succession. In 656 there was the camel battle , the Fitna civil war and in 657 the battle of Siffin on the central Euphrates between ʿAli and his rival Mu'awiya . With the murder of ʿAlī by Kharijites in 661, the series of "rightly guided caliphs" ends.

Timeline

Islamic Studies Concepts for the History of Origin

Modern Islamic studies questions traditional Islamic historiography . In the 1970s, the Revisionist School of Islamic Studies criticized the classic Islamic representation as being religiously and politically motivated. Especially for the early days of Islam, this resulted in a picture of the historical processes that partly deviated from the representations of the 8th and 9th centuries:

The Islamic scholar GR Hawting assumes that Islam did not arise in an environment of ignorance and pagan polytheism. Rather, the multiple references to the texts of the Bible require knowledge of Jewish and Christian teaching. The teachings of the Koran, for example, should contrast the Christian doctrine of the Trinity , which, according to the Islamic understanding of the unity of God, added inappropriate attributes to a more uncompromising concept of monotheism. In order to make the purity of Islamic teaching particularly clear, the pre-Islamic period was polemically presented as ignorant and addicted to pagan polytheism. In later Qur'an commentaries and in traditional Islamic literature, this polemic was taken literally and ascribed to Muhammad's Arab contemporaries. From the standpoint of comparative religious studies, Hawting questions the historical truth of the traditional portrayal of the pre-Islamic Arab religion.

The historical authenticity of the prophetic biographies of Ibn Ishāq and Ibn Hishām , which were only written in the 8th and 9th centuries, was questioned by Hans Jansen . It was assumed that the historical works were supposed to serve the purpose of religiously legitimizing the political rule of the Abbasid caliphs . However, the parish order of Medina is believed to be authentic. With the help of the historical-critical method which was History of the Quran explored. Some scholars question Mohammed as the author and accept later revisions and additions. Fred Donner assumes that Islam emerged as a "movement of believers", in which originally Christians and Jews were also included as equal members, and that a delimitation of the actual Islam only took place since the late 7th century. Individual authors such as Yehuda Nevo and Karl-Heinz Ohlig represent controversial positions with regard to the early days of Islam, such as the fact that Mohammed did not exist as a historical person or was unimportant for the development of Islam. Through linguistic analyzes of the Koran, Christoph Luxenberg proves his hypothesis that the book is written in a mixed Aramaic - Arabic language. As a result, he questions the traditional view of an oral tradition that was complete from the time of Muhammad to the writing of the Koran under ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān . It is based on an older written version. The Koran is based on a partially misunderstood translation of a Syrian, Christian- anti-Trinitarian lesson. This hypothesis, which is relevant from the perspective of critical Koran scholarship, is of lesser importance for the religious or political history of the Islamic world, which is shaped by the traditional understanding of the Koran.

The scientific interest is directed towards the historical development of the world region known today as the "Islamic world" or "Islamic cultural area", as well as the emergence of Islamic social and political structures in the conquered countries. During the first centuries, Islamic expansion was largely carried out by Arabs and is therefore synonymous with “Arab expansion”. In contrast to the descriptions of the early Islamic historians, it is now assumed that the weakness of the Byzantine and Persian Sassanid empires facilitated the conquests. In the early days, an Islamic minority ruled over a majority still predominantly Jewish or Christian. The new Islamic rulers initially took over the existing economic and administrative structures of their predecessors in the conquered areas. The earliest known buildings of Islamic architecture clearly show the adoption and cultural transformation of architectural and artistic design principles of the Syrian-Byzantine tradition. Buildings such as the Dome of the Rock , erected under the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik in Jerusalem, were analyzed in terms of their importance as early symbols of an Islamic consciousness of rule, as were the Islamic coinage that appeared a little later and made the caliphs' claim to power visible in everyday life.

Loss of religious unity

As early as 660, Muʿāwiya established a counter-caliphate in Damascus . The dispute between Muʿāwiya and ʿAlī led the Kharijite opposition movement in 661 to carry out attacks on Ali and Mu'awiya at the same time. Muʿāwiya survived, became a caliph, and established the Umayyad dynasty. The Battle of Karbala on October 10, 680 manifested the division of Muslims into Sunnis and Shiites when Muhammad's grandson and son ʿAlis, Hussein , were killed. As a result, civil wars ( Fitna ) broke out up to 692 .

After the split, the Shiites were led by imams who were descendants of ʿAlī ibn Abī Tālib and Fatima , the daughter of Mohammed. The question of legal succession remained controversial. By the 9th century, the main Shiite branches had emerged, the Imamites ("twelve Shiites"), Ismailites ("seven Shiites") and Zaidites ("five Shiites"). The Ismailis recognized as the rightful successor of Jafar al-Sadiq not Mūsā al-Kāzim , but Ismail ibn Jafar - hence their name. Ismail's son Muhammad was regarded by his followers as the seventh imam (hence the term "Seventh Shiites") and is said not to have died, but to have gone into a concealment from which he as Qaim ("the rising one", "the rising one") or Mahdi would return.

In the middle of the 9th century, Abdallah al-Akbar (d. After 874) began to appear as a representative for Mahdi Muhammad ibn Ismail. He announced the appearance of the hidden seventh imam, through whom the Abbasids should be overthrown, all religions of the law (besides Christianity and Judaism also Islam ) should be abolished and the cultless original religion should be established. He gathered a community around him and sent missionaries ( Dāʿī ) to all parts of the Islamic world . After Abdallah's death, his son Ahmad and grandson Abu sch-Schalaghlagh took over management. The latter found followers especially in the Maghreb , where Abū ʿAbdallāh al-Shīʿī also worked. Abu sh-Schalaghlagh designated his nephew Said ibn al-Husain as his successor, who appeared as the real Mahdi. This in turn triggered a split in the Ismailis, as the Qarmatians and other groups continued to hold on to the expectation of the hidden Mahdi Muhammad ibn Ismail.

After Abū ʿAbdallāh al-Shīʿī had won followers among the Berbers of the Maghreb, he overthrew the Aghlabid dynasty in Ifrīqiya , who had ruled what is now eastern Algeria, Tunisia and northern Libya. In doing so, he paved the way for Abdallah al-Mahdi , who founded the Fatimid dynasty in Ifriqiya .

Islamic expansion and dynasties up to 1000

Arab-Byzantine Wars (632-718)

- 635: Conquest of Syria ;

- 636: Battle of Jarmuk in today's Jordan ;

- 639: conquest of Armenia and Egypt ;

- 642–697 / 8: conquest of the Maghreb ;

- 674–678: First siege of Constantinople ;

- 717–718: Second siege of Constantinople ;

At the beginning of the 8th century, the Byzantine Empire was limited to Asia Minor , the city of Constantinople and some islands and coastal areas in Greece .

Conquest of the Sasanian Empire

After the death of Chosraus II , the Persian Empire, exhausted in the wars with the Byzantine Empire, found itself in a position of weakness in relation to the Arab invaders. At the beginning the Arabs tried to get hold of the peripheral areas ruled by the Lachmids . The border town of Al-Hīra fell into Muslim hands in 633. Under the reign of the last great king Yazdegerd III. the Persians reorganized and in October 634 they won a final victory in the Battle of the Bridge .

After the victory against Byzantium in the Battle of Yarmuk 636, ʿUmar was able to move troops to the east and intensify the offensive against the Sasanids. In southern Iraq there was (probably 636) the battle of al-Qādisīya , which ended with the defeat and the withdrawal of the Sasanian troops. The capital, Ctesiphon, had to be abandoned. In 642 the Persian army was defeated again in the battle of Nehawend . Yazdegerd III. was murdered in the course of internal power struggles in 651 in Merw . By the middle of the 7th century, all of Khusistan was under Arab control.

In 1980, the Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein used the battle of al-Qādisīya for propaganda support of the invasion of Chusistan, which marked the beginning of the Iran-Iraq war (1980–1988).

Expansion to India

As early as 664, 32 years after Muhammad's death, the governor of Khorasan , al-Muhallab ibn Abi Sufra , advanced to Multan in what is now Punjab . The Umayyad armies reached the Indus in 712 ; further conquests were initially halted with the defeat of Muhammad ibn al-Qasim in the Battle of Rajasthan in 738. At the same time, trade contacts between Arabs and Indians expanded, with branches of Arab traders opening up in the port cities of the Indian west coast. The first mosque was built in Kasaragod as early as 642 . Conditions on the upper Indus were less peaceful, where the Muslim rulers in Persia repeatedly came into conflict with the rulers of Sindh without initially achieving territorial gains.

Of special importance was the after in today's Afghanistan town of Ghazni named Turkic dynasty of the Ghaznavids . It was 977 established and attacked by Mahmud of Ghazni ( 998 - 1030 ) in 17 campaigns, the Indus, the movable cavalry of the invaders proved superior with his elephants in battle the Indian Fußheer, but considerable caused by the climatic conditions of India supply problems especially for the invaders' horses. The Ghaznavids managed to establish themselves in the Punjab . At the same time, a first cultural bloom took place at the court of the Ghaznavids; The poet Firdausi and the scholar and doctor Al Biruni worked there , who wrote a book on the history of India ( Kitab Tarich al-Hind ) in addition to a famous theory of medicine . In addition to the armed conflicts, a cultural exchange can already be observed here.

In 1186 the Ghurids overthrew , in 1192 Muhammad von Ghur was able to establish a confederation of Indian Rajputs under the leadership of the Prince of Delhi , Prithviraj III. Defeat Chauhan in the Battle of Taraori . Muhammad then moved into Delhi. In 1206 he was murdered by his general Qutb-ud-Din Aibak , who thus founded the Sultanate of Delhi .

Expansion to East Asia

South East Asia

Islam reached maritime Southeast Asia in the 7th century through Arab traders from Yemen , who traded mainly in the western part of what is now Indonesia and Sri Lanka . Sufi missionaries translated works of their literature from Arabic and Persian into Malay ; For this purpose, an Arabic writing system was developed with the Jawi script, in which the Malay language can be written. In 1292 Marco Polo visited Sumatra on his return journey by ship from China , and reported from there that the vast majority of the population had converted to Islam.

In 1402 Parameswara founded the Sultanate of Malacca . From Malacca, Islam continued to spread to the Malay Archipelago . In 1511 the Portuguese conquered the seat of government with the city of Malacca, after which the sultanate fell apart. While Malacca remained a colonial center of the Portuguese in East Asia for 130 years, various smaller sultanates emerged on the Malay Peninsula, such as the Sultanates of Johor and Perak . In 1641 the Dutch conquered the Portuguese Malacca. It marked the beginning of the decline of the Portuguese colonial empire in Southeast Asia and the rise of the Dutch East Indies colony . In 1824 Malacca fell to the English.

China

Trade already existed between pre-Islamic Arabia and the south coast of China; There were also connections between the Central Asian peoples and the Islamic world, not least via the old trade route of the Silk Road . By the time of the Tang Dynasty at the latest , a few decades after the Hijra , Islamic diplomats also reached China. One of the oldest mosques in China, the Huaisheng Mosque , was built in the 7th century.

Umayyads and Abbasids

Umayyads (Damascus: 661–750, Córdoba –1031)

The Umayyads belonged to the Arab tribe of the Quraish from Mecca . The dynasty ruled from AD 661 to 750 as caliphs from Damascus and established the first dynastic succession of rulers in Islamic history (see table of Islamic dynasties ). The Umayyads of Damascus distinguish between two lines, the Sufyānids , who can be traced back to Abū Sufyān ibn Harb , and the Marwānids , who ruled from 685 , the descendants of Marwān ibn al-Hakam .

Under the Umayyad government, the borders of the empire were extended in the east to the Indus and in the west to the Iberian Peninsula , where the new province of Al-Andalus arose. After their expulsion from the Mashrek by the Abbasids , they founded the Emirate of Córdoba in al-Andalus in 756 , where they ruled until 1031, and since 929 again with the title of caliph. In the east the Indus was reached in the same year. Transoxania with the cities of Bukhara and Samarkand and the region of Khoresmia south of the Aral Sea also came under Islamic rule.

The Battle of Tours and Poitiers in 732 was viewed by the European side as "saving the West from Islam" by Karl Martell , but it was more likely a skirmish between Frankish troops and a smaller Muslim troop on a raid (ghazwa) against Eudo of Aquitaine . The fortresses of Narbonne , Carcassonne and Nîmes and parts of Provence initially remained Muslim.

Mint reform of Abd al-Malik (696)

The first decades of Umayyad rule are characterized by the active appropriation and transformation of ancient art and architecture that the conquerors found in the newly appropriated areas. The emerging political, economic and religious self-confidence of the Islamic rulers can be traced on the basis of coinage.

In the first fifty years of Islamic expansion , the Islamic conquerors initially continued to use the existing coins of the emperor Herakleios and his successor Constans II . Coins from these two emperors have been archaeologically proven in almost all Syrian sites from this time and must have been minted in Byzantium and exported to Syria. In the late ancient Iranian Sassanid Empire , a largely monometallic silver currency was used, the Eastern Romans minted gold , bronze and copper coins. In the earlier Sassanid provinces, after the Arab conquest, silver drachmas and gold dinars with portraits of Chosrau II or Yazdegerd III continued to be used. used on the obverse and a fire temple on the lapel . Only the date was changed, a short pious legend was added , often the Basmala , and the name of the ruler. Occasionally there are also Islamic symbols or portraits of Muslim rulers.

The import of coins from the Byzantine Empire came to a standstill around 655–658. From 696, the year of the Umayyad Abd al-Malik's coin reform , a bimetallic currency system consisting of gold ( dinar ) and silver coins ( dirham ) was used in his domain . The dinar, introduced in 696, is a gold coin modeled on the Byzantine solidus . The portrait of the Byzantine emperor was replaced by the image of the caliph , later completely by aniconical, purely epigraphic pieces.

The minting of one's own, standardized coins presupposes the existence of a well-organized and differentiated administration as early as Abd al-Malik's time. The new coins reached every inhabitant of the ruled areas, the distribution of the new coins without a picture demonstrates the power of the caliphs. The issuance of own coins facilitates the collection of taxes and thus the financing of the immense construction activity of the caliphs of Damascus in Bilad al-Sham as well as the salary of the standing army, which was paid in cash in dirhams according to wages set in registers.

Gold and silver coins of the Islamic rulers were already a common means of payment in the 8th century. They can be found in large numbers in Scandinavian hoard finds such as the Scottish Skaill hoard and grave goods from the Viking Age and bear witness to the far-reaching trade relations of the Islamic world.

Timeline

Abbasids (750–1258)

Legal scholars from the Abbasid period

· Abu Hanifa

· Mālik ibn Anas

· asch-Shāfiʿī

· Ahmad ibn Hanbal

· Jaʿfar as-Sādiq

Scientists and poets of Abbasidenreichs

· Hunayn ibn Ishaq

· Ibn Fadlan

· al-Battani

· at-Tabari

· al-Battani

· Rhazes

· al-Fārābī

· Alhazen

· al-Biruni

· Omar Khayyam

· al-Hallaj

· Al-Kindi

· Avicenna

The Abbasid dynasty ruled from 749 to 1258. It descends from al-ʿAbbās ibn ʿAbd al-Muttalib , an uncle of Mohammed, and thus belongs to the Hashimite clan . It came to power in the course of the Abu Muslim revolution . At the beginning of their rule they conquered the Mediterranean islands including the Balearic Islands and 827 Sicily . Abu l-Abbas as-Saffah (died 754) was the first Abbasid ruler.

In the 9th and 10th centuries, the first Islamic local dynasties were established in some provinces :

- the Arab Idrisids (789–985) in the western Maghreb, today's Morocco ,

- the Arab Aghlabids (800–909) in Tunisia and Tripolitania ,

- the Turkish Tulunids (868–906) and Ichschidids (935–969) in the Nile Valley (Egypt),

- the Persian Tahirids (821–873) and Samanids (873–999) in north-east Persia and Transoxania .

The borders of the empire remained stable, but there were always conflicts with Byzantium, such as 910 about Cyprus , 911 about Samos and 932 about Lemnos .

"The heyday of Islam"

As-Saffar's successor al-Mansur (r. 754–775) founded the city of Baghdad and made it the new center of the Islamic empire. Mansur's grandson Hārūn ar-Raschīd (ruled 786–809) is probably the most famous ruler of the Abbasid dynasty, immortalized in the fairy tale of the Arabian Nights . The caliph Al-Ma'mun (813-833) and some of his successors promoted the theological direction of the Muʿtazila , which was strongly influenced by Greek philosophy and placed free will and rationality in the foreground of their teaching, as well as the origin of the Koran . Intellectuals like Al-Kindi (800-873), ar-Razi (864-930), al-Farabi (870-950) and Avicenna (980-1037) are representatives of the Islamic intellectual life of their time as a golden age of Islam is called .

Timeline

Unity and diversity of Muslim society

A fundamental characteristic of Islamic society was and is the tension between the ideal of the unity of faith and the reality of cultural diversity in the vast Islamic world. This tension is also very present today. Since the time of the Prophet and his immediate successors, the religious message of Islam has reached different peoples with different traditions. It was and remains a challenge to establish and enforce common norms based on the most diverse traditions. Nevertheless, this diversity was and is a source of significant cultural vitality.

Standardization

The Koran and the sayings and actions ( Sunna ) of the Prophet handed down in the Hadith form the basis of the Islamic finding of norms ( Fiqh ). Further canonical sources of legal finding are the consensus of qualified scholars ( Idschmāʿ ) and the conclusion by analogy ( Qiyās ). Even individual scholars ( mudschtahid ) can set norms from their own judgment ( ijschtihād ). The Islamic legal theory ( Usūl al-fiqh ) deals with the sources and methodological foundations of norms. The resulting set of rules for a godly way of life, the Sharia , encompasses the religious and secular life understood as a unit. Failure to meet social obligations is therefore just as serious as an apostasy from Islam, as is denial of the oneness of God ( Tawheed ) or the legitimacy of the prophet's teaching.

Concept of state

In contrast to Christianity, for example, which had no political power in the first centuries of its existence, Islam already had uniform political and administrative structures in its earliest epoch. In the course of its rapid expansion, the Islamic community gained direct access to the concepts of ancient philosophy and its logical way of working and was able to fall back on existing administrative and economic structures. In a slow process, Islamic society developed under the influence of the pre-existing pre-Islamic cultures.

Preservation and enforcement of Sharia law, defense of the Ummah against external enemies and the spread of Islam in the “holy war” ( jihad ) require political power. Political action was therefore the fulfillment of religious duties. The loss of the religious unity of Islam made a detailed elaboration of the Islamic understanding of rule necessary. Since the 8th century, Islamic philosophers and legal scholars such as Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi (around 872–950) developed theories about the ideal community. In 10./11. In the 19th century, the Shafiite legal scholar Abū l-Hasan al-Māwardī (972-1058) and the Ashʿarite scholar Abū l-Maʿālī ʿAbd al-Malik ibn ʿAbdallāh al-Juwainī (1028-1085) presented fundamental considerations on the state model of the caliphate ( Imamat ). The Hanbali scholar Ibn Taimīya (1263-1328) developed the idea that the right to be based on statements of the Koran and the prophetic tradition (Sunna) and that a state has to guarantee the enforcement of Sharia law.

Urban and rural populations

The historian and politician Ibn Chaldūn (1332-1406) analyzed the political and social conditions in the Maghreb in the 14th century. In his book al-Muqaddima he analyzed in detail the relationship between rural Bedouin and urban settled life, which depicts a social conflict that is central to him . The historical development of medieval society in the Arab-Islamic world was determined by two social contexts, nomadism on the one hand and urban life on the other. With the help of the concept of ʿAsabīya (to be translated as “inner bond, clan loyalty, solidarity”) he explains the rise and fall of civilizations, where the belief and the ʿAsabīya can complement each other, for example during the rule of the caliphs . The Bedouins and other nomadic inhabitants of the desert regions ( al-ʿumrān al-badawī ) have a strong ʿAsabīya and are more firm in their faith, while the inner cohesion of the city dwellers ( al-ʿumrān al-hadarī ) loses more and more strength over the course of several generations . After a span of several generations, the power of the urban dynasty based on the ʿAsabīya has shrunk to such an extent that it becomes the victim of an aggressive tribe from the land with the stronger ʿAsabīya , who, after conquering and partially destroying the cities, establishes a new dynasty.

From the 10th century onwards, the contrast between the highly developed dynastic hereditary monarchies of Persian origin and the nomadic traditions of the Turkic peoples who immigrated in large numbers from this time onwards, with their principles of succession according to the seniority and the dependence of the ruler on the loyalty of his tribe, shaped the political development of the Islamic world. Under the Seljuq rulers Alp Arslan (1063-1072) and his successor Malik Şâh (1072-1092), both supported by their capable Grand Vizier Nizām al-Mulk , it was possible to unite the two different traditions in one political system.

In the course of the confrontation with colonialism, the political contrast between the urban-modern urban population and the rural population, which was more firmly attached to tradition, gained importance again, especially after the First World War, and was to shape the political events of many societies in the Islamic world. For the first time, colonial administrative structures included the entire population; This led to a new perception of one's own society within the national borders dictated by the colonial rulers, and ultimately to the emergence of nation-state concepts, which until the end of the 20th century were to shape the political discourse more than the appeal to the unity of the Islamic world.

Islamic elites

ʿUlamā '- the legal scholars

The Koran and Hadith had been widely recognized as the main sources of divine order since the 9th (3rd Islamic) century. The Sharia codifies the guidelines on piety and religious devotion. Since the 9th century a network of scholars of jurisprudence ( Fiqh ) had emerged, the ʿUlamā ' , whose task it is to interpret and enforce the details of the divine commandments. In contrast to the centralized hierarchy of the Christian Church, participation in the ʿUlamā 'is not tied to an ordination and has never been directed and monitored by a central institution. For many Muslims, the combination of divine guidance and guidance from the ʿUlamā '( Taqlid ) is sufficient as the basis of their religious life.

Sufis - the mystics

Some Muslims developed a need to experience the divine in ways other than law and interpretation. The Sufism has an emotional, more accessible way to religious experience and is sometimes viewed as a conscious reaction against the rationalist tendencies of jurisprudence and systematic theology. The Sufi masters ( sheikhs , pir , baba ) and their students offered a supplement and sometimes an alternative to the legal scholarship of the ʿUlamā '. In North India in the 11th, Senegal in the 16th, and Kazakhstan in the 17th century it was Sufi missionaries who introduced Islam to the population, also by adopting local traditions of “popular piety” more freely than legal scholars. Some of them opposed the teachings of the Sufis, but the movement never came to a complete standstill. In the last decades of the 20th century, Sufism found increasing interest again, especially among the educated middle class.

Ruler

A third stream of Islamic self-image, alongside ʿUlamā 'and Sufis, is the “ruling” Islam of the Islamic monarchs. With the loss of political unity at the end of Abbasid rule and the destruction of Baghdad in the Mongolian storm in 1258 , the office of caliph lost its original meaning. The form of government of the sultanate brought political power into the hands of rulers who based their power on the military and administration, and whose primary goal was to maintain their monarchy ( mulk ). Laws passed by the Sultan were guided by the interests of the state and enforced by the political elite. Formally, the sultan, after he had inherited or usurped rule, was installed by the caliph and recognized in the Baiʿa ceremony . The originally comprehensive social order of the Sharia turned into a negative principle, an order that the ruler should not break. In the eyes of the ʿUlamā 'the task of the secular ruler was to secure the society internally and externally so that the Sharia could be enforced and the community could prosper. The monarch guaranteed the existence of the ʿUlamā 'and established and promoted the universities . In order to be able to assert his interests against the āUlamā ', the rulers appointed muftis , whose task it was to prepare legal opinions ( fatwa ). Still, the question arose as to whether a secular monarch could be the legitimate head of the Islamic community.

According to al-Māwardī , the caliph had the right to delegate military power to a general ( amir ) in the outer areas of his territory, as well as to rule inside through deputies ( wasir ). Two hundred years later, al-Ghazālī defined the role of the imam as - according to the Sunni understanding - the legitimate ruler of the umma, who delegates real power to the monarch and calls on the faithful to obey and thus maintain the unity of the umma. In al-Ghazālī's ideas, elements of Classical Greek philosophy, especially from Plato's “Politics” and the ethics of Aristotle with the old Persian concept of the great king, find their way into Islamic social philosophy . In his work " Siyāsatnāma " Nizām al-Mulk , the Persian Grand Vizier of the Seljuk sultans Alp Arslan and Malik Schāh, describes the new concept of rule in the style of a prince's mirror .

An Islamic monarch had considerable resources at his disposal due to the taxes he received from zakāt and jizya , which enabled him to maintain court manufactories that shaped the culture and art of their time. From the point of view of ruling Islam, successful wars, representative art, magnificent architecture and literature ultimately served to represent the primacy of Islam. In this role, Islamic rulers created some of the most remarkable achievements of premodern Islamic civilization.

Conflicts of authority between the elites

The question of to what extent a separation of political and religious authority can be assumed from the time of the Umayyads (661–750) is controversial. Clearly, however, the lack of central leadership comparable to that of the Christian church led to a pronounced and at times paralyzing diversity in religious and legal issues. It becomes clear that the institution of the āUlamā 'had to protect itself from the ruler's encroachments on its authority in the judiciary. On the one hand, the plurality of the ʿUlamā ', which contradicts the ideal of religious unanimity, protected it from direct influence by the state. The fuzzy separation of political and religious legal authority is based on the idea, which has never been fundamentally questioned, that Mohammed and his successors finally determined the political order. This distinguishes the political order of Islamic societies from the development in Europe, where with the emergence of the idea of the separation of powers , formulated by John Locke , a separation of political and religious responsibility and the independence of the judiciary was ultimately achieved.

The tension between the charismatic ideal of the unity of religion and state and the experience of everyday political reality forms a latent source in Islamic culture for dynamic reforms, but also for rebellion and war in the name of the unity of Islam. Modern political thinking in parts of the Islamic world has picked up on this tension and sometimes exaggerated it to the point of terrorist violence .

Dhimmi - Christians and Jews

Especially during the early period of Arab expansion, a Muslim minority ruled over a population that was predominantly Christian. At the same time, important Jewish communities had existed in the now Islamic-ruled areas from time immemorial. Christian authors linked the conquest of the Christian territories in part with the apocalypse which was soon to come. Large parts of the conquered areas initially remained Christian or Zoroastrian. A Nestorian bishop writes: “These Arabs, whom God has given rule in our day, have also become our masters; however, they do not fight the Christian religion. Rather, they protect our faith, respect our priests and saints and make donations to our churches and monasteries. "

Since the late 7th century, the increasing self-confidence of the Muslim rulers increased the pressure to assimilate the Christian population . There was discrimination, the exclusion of non-Muslims from the administration, interference in internal Christian affairs and the confiscation of church property and individual attacks on churches.

In the Islamic legal tradition of the dhimma , monotheists such as Jews or Christians are called “ dhimmi ” ( Arabic ذمّي, DMG ḏimmī ) tolerated with limited legal status and protected by the state. According to this, dhimmi had the right to the protection of the sultan and to the free practice of their religion, for which they had to pay a special tax, the “ jizya ”, since they could not be subjected to the zakāt , which was only applicable to Muslims .

Polytheistic Religions

The religious jurisprudence counts "pagan", polytheistic religions in non-Islamic ruled countries to the Dār al-Harb and regulates the conditions under which a jihad can be conducted. This ideal was often opposed to political reality: especially in the early days, the ruling Islamic minority in the newly conquered areas faced a non-Islamic majority.

In the situation of the Sultanate of Delhi , the handling of the problem is exemplarily clear. On the one hand, Amir Chosrau often expresses himself disparagingly about Hindus in his works , on the other hand Muslims had to deal peacefully with followers of polytheistic religions ( " Muschrik ūn" ) such as Hindus and Jains in everyday life and trade . It is said that Muhammad bin Tughluq , as ruler, maintained good relations with his Hindu subjects and showed himself at their festivals. Jackson sees the destruction of Hindu temples by Muslim rulers and the installation of spoils from the temple buildings in mosques such as the Qutub Minar in Delhi more in the tradition of Hindu rulers who wanted to further weaken their rule by destroying the temples of their rivals. But it is also recorded that the Sultans of Delhi extended their protection to Hindu and Jain temples. At the latest at the time of Firuz Shah Tughluq in the 14th century, it is documented that some Hindu subjects paid a poll tax comparable to that of the jizya.

10-15 century

The West in the 10th – 15th centuries century

Al-Andalus (711-1492)

Between 711 and 1492, a large part of the Iberian Peninsula was under Islamic rule. Caliph al-Walid I founded a province of the Umayyad Caliphate (711–750) there. The Umayyad prince Abd ar-Rahman ibn Mu'awiya , fleeing from the Abbasids, landed with Berber troops in Almuñécar in Andalusia in 755 . In May 756 he overthrew the ruling governor of Al-Andalus Yusuf al-Fihri in Cordoba . With his elevation to the rank of emir (756–788) the political organization of the Umayyad Empire began in Spain. Abd ar-Rahman founded the margravates of Saragossa , Toledo and Mérida to secure the border against the Christian empires in northern Spain.

Al-Andalus was successively ruled by the emirs of Córdoba (around 750–929), the caliphate of Córdoba (929–1031), a group of “ Taifa ” (successor) kingdoms, then became a province of the North African Berber Almoravid and Almohad dynasties ; eventually it fell again into Taifa kingdoms. For long periods, particularly during the time of the Caliphate of Cordoba , al-Andalus was a center of learning. Cordoba became a leading cultural and economic center of both the Mediterranean and the Islamic world.

As early as the early 8th century, al-Andalus was in conflict with the Christian kingdoms in the north, which expanded their territory militarily as part of the Reconquista . In 1085 Alfonso VI conquered . of Castile Toledo. After all, after the fall of Cordoba in 1236, the emirate of Granada remained as the last Muslim-dominated area in present-day Spain. The Portuguese Reconquista ended with the conquest of the Algarve by Alfonso III. 1249/1250. Granada became a tribute to that of Ferdinand III in 1238 . ruled the Kingdom of Castile. Eventually the last emir gave Muhammad XII. January 2, 1492 Granada to Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile , Los Reyes Católicos (the "Catholic Kings"), with which the Muslim rule on the Iberian Peninsula came to an end.

Timeline

- Emirs of Cordoba

- Caliphs of Cordoba

Maghreb

Almoravids (670–1149)

Kairouan in Tunisia was founded around 670 by the Arab general baUqba ibn Nāfiʿ , and was the first Muslim city to be founded in the Maghreb . After the 8th century, Kairouan developed into the center of Arab culture and Islamic law in North Africa. The city also played an important role in the Arabization of the Berbers . Kairouan was the headquarters of the Arab governors of Ifrīqiya and later the capital of the Aghlabids . In 909 the Fatimids , Ismaili Shiites , under the leadership of Abū ʿAbdallāh al-Shīʿī, took power in Ifriqiya and made Kairouan a residence. The religious-ethnic tensions with the strictly Sunni population of the city, however, forced them to expand their capital to al-Mahdiya on the eastern sea coast; around 973 they moved the center of their caliphate to Cairo .

The Almoravids , a strictly Orthodox Islamic Berber dynasty from the Sahara, took over rule from the Zirids and expanded their area of influence to include today's Morocco , the western fringes of the Sahara, Mauritania , Gibraltar , the region around Tlemcen in Algeria and part of today's Senegal and Mali in the south. The Almoravids played an important role in the defense of Al-Andalus against the Christian north Iberian kingdoms: in 1086 they defeated the coalition of the kings of Castile and Aragon at the battle of Zallaqa . The rule of the dynasty lasted only a short time, however, and was overthrown by the rebellion of the Masmuda- Berber under Ibn Tūmart .

In 1146, the Almohads took the city of Fez and thus gained control of northern Morocco . When the capital Marrakech was also conquered in 1147, the Almohad caliph Abd al-Mumin eliminated the Almoravid dynasty by killing the last Almoravid ruler Ishaq ibn Ali in the capital Marrakech in April 1149 . The Almoravid rule came to an end in al-Andalus in 1148.

Almohads (1121-1269)

The Almohad dynasty was founded by Ibn Tūmart in 1121 under the Masmuda beers of the High Atlas . It stood in ideological contrast to the Almoravids . Ibn Tūmart's successor Abd al-Mumin (1130–1163) succeeded in overthrowing the Almoravid dynasty with the conquest of al-Andalus (1148) and Marrakech (1149). After Morocco , the Almohads conquered the empire of the Hammadids in today's Algeria (1152) and the empire of the Zirids in Tunisia (1155–1160), thus ruling the entire west of the Islamic world. With the resettlement of Arab Bedouin tribes from Ifrīqiya and Tripolitania to Morocco, the Arabization of the Berbers was also promoted in this part of the Maghreb.

Under Yaʿqūb al-Mansūr (1184–1199) the advances of Castile in al-Andalus could be repulsed in the Battle of Alarcos (1195). In the following years, some provinces gained autonomy under Caliph Muhammad an-Nasir (1199–1213). In al-Andalus, Islamic rule was shaken by the defeat in the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212) against the united Christian kingdoms. When Yusuf II. Al-Mustansir (1213-1224) came to power as a minor and disputes broke out among the Almohad leaders, the decline of the empire began. By 1235, the Almohads had lost control of al-Andalus to Ibn Hud , Ifrīqiya to the Hafsids , and Algeria to the Abdalwadids .

The Almohads continued the architectural style for mosques created by the Abbasids , which is characterized by the T-disposition of a prominent central nave and transept in front of the qibla wall . Examples are the Kutubiyya Mosque in Marrakech and the Tinmal Mosque in the Atlas Mountains .

In Morocco, the Merinids began to expand their power in order to establish a new dynasty after the conquest of Fez (1248). Although the Almohads were able to hold their own against the Merinids in Marrakech until 1269, they had largely lost their importance since the fall of Fez.

Meriniden (1196–1464), Abdalwadiden (1236–1556), Hafsiden (1228–1574)

After the fall of the Almohads, the Maghreb was ruled by three dynasties who fought each other. The Merinids (1196–1464) resided in Morocco. West Algeria was the zayyanid dynasty ruled (1236-1556) and the Hafsids (1228-1574) ruled eastern Algeria, Tunisia and Cyrenaica .

Timeline

Egypt

Turkish Tulunids (869–905), last reign of the Abbasids (905–935)

Around 750 a process began in which the peripheral areas broke away from the central rule of the caliphate. As early as 740–42 there was the Maysara uprising in the far west , some Berber groups made themselves independent, finally in 789 the Idrisids (789–985) broke away from the empire, in 800 the Aghlabids followed . In 868, the former Turkish slave Ahmad ibn Tulun (868-884) first became governor in Egypt, and in 870 he proclaimed independence from the caliphate . Since the tax revenue was no longer paid to the caliphs, it was possible to expand the irrigation systems and build a fleet, which promoted trade and improved protection against attacks by the Byzantine navy . In 878 Palestine and Syria were occupied. Ibn Tulun reinforced his rule by erecting representative structures such as the Ibn Tulun Mosque in Cairo.

Under Chumarawaih (884–896), the Abbasids were able to regain northern Syria for a short time. In a peace agreement, Chumarawaih waived claims in Mesopotamia and agreed to pay tributes. For this, Caliph al-Mu'tadid (892–902) recognized the rule of the Tulunids in Egypt and Syria. Under al-Mu'tadid's rule, the Ismaili Qarmatians expanded into Syria. In 905 Egypt was subjugated again by the Abbasid troops, which started a long chain of clashes. Egypt came under the rule of the Ichschididen in 935 .

Ichschididen (935 / 39–969)

The Ichschididen can be traced back to the Ferghana area, whose princes bore the title "Ichschid". One of them entered the service of al-Mu'tasim. He was the grandfather of the founder of the dynasty, Muhammad ibn Tughj . In 930 he was made governor of Syria by the caliph, and in 933 also of Egypt. He initially continued to recognize the suzerainty of the Abbasid caliphs , from whom he promised support against the Fatimids from Ifrīqiya and in the suppression of Shiite uprisings inside. From 939 he acted increasingly independently of the central administration and ultimately founded the Ichschididen dynasty. Ibn Tughj occupied Palestine, the Hejaz and Syria as far as Aleppo between 942 and 944 . In 945 he concluded an agreement with the Hamdanids on the division of rule in Syria.

The Fatimids succeeded in conquering Egypt in 969 under the Ichshidid ruler Abu l-Fawaris and overthrowing the last representative of the short-lived dynasty, the twelve-year-old Abu l-Fawaris.

Fatimids (969–1171)

Fatimids in North Africa:

· Abdallah al-Mahdi (910-934)

· Abu al-Qasim al-Qaim (934-946)

· Ismail al-Mansur (946-953)

· Abu Tamim al-Muizz (953-975)

Fatimid Egypt:

· Abu Tamim al-Muizz (953-975)

· al-'Azīz (975-995)

· al-Hakim (995-1021)

· Az-Zahir (1021-1036)

· al-Mustansir (1036-1094)

· al-Musta (1094-1101)

· al-Amir (1101-1130)

· al-Hafiz (1130-1149)

· al-Zafir (1149-1154)

· al-Faiz (1154-1160)

· al-'Ādid (1160 –1171)

In 909 Abdallah al-Mahdi proclaimed himself caliph and thus founded the Fatimid dynasty, which derived its name from Fātima bint Muhammad . Under his son al-Qa'im bi-amri 'llah , the conquest of the western Maghreb began in 917. Under Abu l-Qasim al-Qaim (934–946) Sicily was conquered and the coasts of Italy and France sacked. Ismail al-Mansur (946–953) succeeded the second Fatimid ruler, who died in 946 . After the end of the revolt of the Kharijite Banu Ifran (944-947), the third Fatimid caliph took the nickname "al-Mansur". In Kairouan emerged with el-mansuriya a new residence. After the reorganization of the empire by Ismail al-Mansur and Abu Tamin al-Muizz (953–975), the Fatimids succeeded in advancing to the Atlantic , but rule over Morocco could not be maintained.

In 969 the Fatimid general Jawhar as-Siqillī conquered Egypt and overthrew the Ichschidid dynasty. Caliph al-Muizz moved his residence to the newly founded city of Cairo in 972 and established the Zirids as viceroys in the Maghreb. By 978 Palestine and Syria were also subject; with the protectorate of Mecca and Medina they also gained control of the most important shrines of Islam.

Under her rule, Egypt's economy flourished by building roads and canals and promoting trade between India and the Mediterranean. Culture and science were also promoted by the Fatimids, with the establishment of the al-Azhar University becoming extremely important. It is still a Sunni center and one of the most important universities in the Islamic world. In the 10th century, an-Nuʿmān founded the Ismaili school of law , which, along with the four Sunni and the Twelve Shiite schools of law, is one of the six most important legal traditions ( madhhab ) of Islam.

Under Al-Hakim (995-1021) the previously tolerant attitude of the Ismaili Fatimids towards non-Muslims became significantly more severe. Public acts of worship by Christians and Jews as well as the consumption of alcohol were forbidden. Christian churches and monasteries were looted to raise funds for the army and the building of mosques. In 1009 the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem was destroyed. Around 1017, a sect emerged in Egypt that regarded al-Hakim as the incarnation of God. The Druze religious community later developed from this .

Az-Zahir (1021-1036) succeeded in pacifying the empire and suppressing some Bedouin revolts in Syria. The Fatimids under al-Mustansir (1036-1094) reached the height of their power when Ismaili missionaries seized power in Yemen and the Abbassids in Baghdad briefly lost their position of power in 1059.

In 1076 Syria and Palestine were lost to the Seljuks . The Fatimids could no longer prevent the conquest of Jerusalem by the Crusaders during the First Crusade in 1099 and the establishment of the Kingdom of Jerusalem . After unsuccessful attempts to recapture them ( Battle of Ramla ), they came under increasing military pressure from the crusaders from 1130 onwards. With the conquest of Ascalon by King Baldwin III. of Jerusalem the last base in Palestine was lost in 1153. To forestall a conquest of Egypt by the Crusaders, Nur ad-Din , the ruler of Damascus, led a campaign into Egypt in 1163. His general Saladin overthrew the Fatimids in 1171 and founded the Ayyubid dynasty .

Even if, with the rise of the Orthodox Sunnis, especially in Iran since the 11th century, their influence diminished, the Ismaili communities continued to exist even after the end of the Fatimid dynasty.

As early as the beginning of the 11th century, the Zirids split off in Ifriqiya , who returned to Sunni Islam and recognized the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad. The Fatimids used the Bedouins of Banū Hilāl and Sulaim against them , who devastated the Maghreb . The Zirids could only survive on the coast (until 1152).

Timeline

Ayyubids (1174-1250)

The Ayyubids were an Islamic-Kurdish dynasty that fought against the Christian crusaders under Saladin . In 1174 Saladin proclaimed himself sultan. The Ayyubids ruled Egypt until around 1250. They were able to recapture Tripoli (1172), Damascus (1174), Aleppo (1183), Mosul (1185/86) and Jerusalem (1187) from the Crusaders and ruled them during the 12th and 13th centuries. Century Egypt, Syria, northern Mesopotamia, the Hejaz , Yemen and the North African coast up to the border of today's Tunisia. After Saladin's death, his brother al-Adil I took power. Around 1230, the Ayyubid rulers in Syria sought independence from Egypt, but the Egyptian sultan As-Salih Ayyub managed to regain much of Syria - with the exception of Aleppo - in 1247. In 1250 the dynasty was overthrown by Mamluk regiments. The attempt by-Nasir Yusufs to win back the empire from Aleppo failed. In 1260 the Mongols sacked Aleppo and finally put an end to the dynasty.

Timeline

Mamluks (1250–1517)

Mamluken , also Ghilman , were military slaves of Turkish origin imported into many Islamic-dominated areas . Various ruling dynasties founded by such (former) military slaves are also known as Mamluks. So Mamluks came to power in Egypt in 1250 , extended them ten years later to the Levant and were even able to successfully assert themselves against the Mongols from 1260 onwards. In 1517 the Egyptian Mamluks were subjugated by the Turkish Ottomans , but still ruled Egypt on behalf of the Ottomans until the Battle of the Pyramids .

Crusades (1095-1272)

In the 8th century, the Iberian Christian kingdoms began the Reconquista to reclaim Al-Andalus from the Moors . In 1095 Pope Urban II called on the Synod of Clermont for the First Crusade , prompted by the first successes of the Reconquista and strengthened by the request of the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos for help in the defense of Christianity in the east . The county of Edessa , Antioch on the Orontes , the region of the later county of Tripoli and Jerusalem were conquered. The Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem and other smaller crusader states played a role in the complex politics of the Levant for the next 90 years , but posed no threat to the Caliphate or any other powers in the region. After the end of Fatimid rule in 1169, we saw the Crusader states increasingly exposed to the threat of Saladin , who was able to recapture a large part of the region by 1187.

In the Third Crusade it was not possible to conquer Jerusalem, but the crusader states continued to exist for a few decades. The Reconquista in Al-Andalus was completed in 1492 with the conquest of the Kingdom of Granada . The Fourth Crusade did not reach the Levant, but instead was directed against Constantinople . This further weakened the Byzantine Empire. After William of Malmesbury , the crusades had the consequence that the further advance of Islam towards Europe was stopped.

According to today's understanding, the crusades, which ultimately only directly affected a small part of the Islamic world, had a comparatively small effect on Islamic culture per se, but permanently shook the relationship between the Christian societies of Western Europe and the Islamic world. Conversely, for the first time in history, they brought Europeans into close contact with the highly developed Islamic culture , with far-reaching consequences for European culture.

The East in the 11th-15th centuries century

Seljuks (1047-1157)

Immigration of Turkic peoples

In the 8th century hiked a group of the Turkic peoples belonging to Oghuz , the Seljuks, from today's Kazakh Steppe after Transoxania and took the area around the river Syr Darya and the Aral Sea in possession. The tribal group was named after Seljuk (around 1000), Khan of the Kınık Oghuz tribe . Towards the end of the 10th century, the Seljuks had converted to Islam. In the clashes between the Turkish Qarakhanids and the Persian Samanids , Oghusen served as mercenaries in the armies. In 1025 the Ghaznawide captured Mahmud of Ghazni Seljuk's son Arslan; he died shortly afterwards.

Under the sons of Mîka'îl, Tughrul Beg and Tschaghri Beg , the Seljuks brought Khorasan under their rule in 1034 . 1040 they defeated in the battle of dandanaqan , one of the decisive battles in the history of the eastern Islamic world, the Ghaznavids . In 1055 Tughrul moved into Baghdad , ended the rule of the Buyid dynasty and claimed protection over the Abbasid caliphate and the title of sultan . Tughrul Beg succeeded in conquering large parts of Persia and, in 1055, Iraq . He made the city of Rey near what is now Tehran the capital of his dynasty. The emerging empire of the Greater Seljuks established the dominance of Turkic peoples in the Islamic world and marked a turning point in the history of Islamic civilization.

Greater Seljuk Empire

Alp Arslan (1063-1072) defeated the Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes in the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 and thus initiated the Turkish settlement of Anatolia . Alp Aslan and his successor Malik Şâh (1072-1092) led the kingdom of the Greater Seljuks to its political and cultural climax. The areas of Jazira , northern Syria, right up to Khoresmia and the Amu Darya , were under direct administration by the Seljuks ; Turkmen groups in Anatolia, the Central Asian regions of the Karakhanids , while the Fatimids from southern Syria and Palestine (dem old picture al-Sham) were suppressed. Successful campaigns were carried out on the Arabian Peninsula as far as today's Yemen .

Introduction of Persian administrative structures by Nizam ul-Mulk

Both Alp Arslan and Malik-Shah owe a large part of their success to the capable politics of their Persian vizier Nizam al-Mulk , who later supported the Malik-Shah as tutor ( Atabeg ) during his twenty-year rule. al-Mulk ruled the empire with the help of Dīwan al-Wāzīr , the great council, which had its seat in the new capital, Isfahan . He secured the loyalty of the administrative authorities by filling the offices with his numerous sons and relatives. He introduced the Persian-Islamic style of administration with several Dīwānen in a dynasty that was only three generations separated from its Turkic nomadic origins. In contrast to the traditional succession of the Turkic peoples, which was based on seniority , in the Seljuk dynasty he established the Persian concept of the great king ( Shahinschah , Persian شاهنشاه, DMG šāhān-šāh , 'King of Kings'). The government was supposed to awe the subjects on the one hand, and on the other hand the ruler had to take into account the traditions of the still sedentary Turkmens who, according to the tradition of the steppe peoples, were his most important supporters.

Toghrul, like other Islamic rulers before him, recognized the importance of a standing army, which they maintained alongside their Turkmen supporters, who had to be summoned whenever necessary. The core of this army were mercenaries of Turkic origin, ghulām , but the army also recruited mercenaries from warlike tribes of the empire and its peripheral areas, such as the Arabs, Armenians and Greeks. The army was financed through land allocation ( Iqta ), but also through taxes. When the power of the Seljuk sultans declined in the 12th century, some leaders of the ghulām troops established independent spheres of power, such as the Atabegs in Azerbaijan or the Salghurid -Atabegs of Fars .

Nizam al-Mulk recorded his ideas on statecraft in a book, the siāsat-nāmeh . He founded a number of universities, named after him as Nizāmīya , in order to train scholars and officials in the Sunni tradition, and thus to form an attractive counterpoint to the Fatimid al-Azhar in Cairo, which is in the Ismaili-Shiite tradition . From 1086-1087 he had the south dome built over the mihrab niche of the Friday Mosque of Isfahan , which today is part of the world cultural heritage with the adjacent Grand Bazaar in the southeast , and is considered a key work of the architecture of the Islamic East due to its long architectural history .

Division of empire and end

After the murder of Nizam al-Mulk by the assassins and the death of Malik-Shah a short time later (1092), a succession dispute broke out. In 1118 the empire was divided into Khorasan / Transoxania and the two Iraq , in the area of western Iran and Iraq . Around 1077 Suleiman ibn Kutalmiş founded the Sultanate of the Rum Seljuks in Anatolia with the capital Konya. The Kerman-Seljuks dynasty, founded in 1048, goes back to Alp Arslan's brother Qawurd Beg .

The Sultan Sanjar (1118–1157), son of Malik-Shah II, who ruled in Khorasan, was defeated in 1141 near Samarkand by the Kara Kitai . The Khorezm Shahs conquered Central Asia and Iran with the help of Cypriot and Oghuz mercenaries by the end of the 12th century . In 1194 they eliminated the last Seljuk ruler of Rey . The Anatolian Sultanate of the Rum Seljuks existed until the conquest by the Ilkhan (1243). The Ottomans , who emerged at the beginning of the 14th century, put an end to the last Seljuk Sultanate in Konya in 1307.

Khorezm Shahs (1077-1231)

Khorezmia ( Persian خوارزم, DMG Ḫwārizm ) is a large oasis in western Central Asia . It lies on the lower reaches and the mouth of the Amudaryas , and is bordered in the north by the Aral Sea , the Karakum and Kyzylkum deserts and the Ustyurt plateau . Neighboring provinces were Khorasan and Transoxania in Islamic times . As early as 712, Khorezmia was subjugated and Islamized by the Arabs . From the 10th century onwards, the country was ruled by the Samanids , Mamunids, Ghaznavids , Altuntaschids , Oghusen and Greater Seljuks . In the 12th century, the land made fertile by a sophisticated irrigation system, the cities of which were conveniently located on the trade routes between the Islamic countries and the Central Asian steppe, experienced a period of economic strength. The simultaneous political and military weakness of the Qarakhanids and the Seljuks made it possible for the Khorezm Shahs from the Anushteginid dynasty to establish a powerful military empire.

founding

The dynasty of the Anushteginids was founded by Anusch-Tegin Ghartschai , a Turkish military slave ( Ġulām or Mamlūk ), who was appointed governor of Khoresmia by Malik-Shah I around 1077. In contrast to their usual custom, the Seljuks in Khorezmia allowed the office of governor to become hereditary: Anush-Tegin's son Qutb ad-Din Muhammad managed to consolidate his power to such an extent during his roughly 30-year reign that his Son Ala ad-Din Atsiz could inherit office and title from father in 1127/8. From 1138 he rebelled more and more against the Seljuks under their last great Sultan Ahmad Sandschar . As part of a consistently pursued expansion policy, Atsiz conquered the Ustyurt plateau with the Mangyschlak peninsula and the region on the lower reaches of the Syrdarja with the important city of Jand (Ǧand).

Atsiz's son and successor Il-Arslan was able to rule largely independently of the Seljuks after the death of Sultan Sandjar (1157), but Khorezmia was still tributary to the pagan Kara Kitai who had been expelled from China to the west until around 1210 , whose Gur- Khan Yelü Dashi Sandjar in the battle of Qatwan (September 1141) inflicted a defeat and thus subdued almost all of Turkestan .

Peak of power under Ala ad-Din Muhammad

Together with Uthman Chan, the Karakhanid ruler of Samarqand , Ala ad-Din Muhammad (1200-1220) succeeded in defeating the Kara Kitai around 1210 in the Battle of Taras . Around 1210 Ala ad-Din Muhammad subjugated the Bawandid dynasty of Mazandaran , as well as Kirman , where the Qutlughchanids, descended from the Kara Kitai, established a local dynasty in 1222–1306, Makran and Hormuz . By 1215, all non-Indian areas of the disintegrated Ghurid Empire - essentially today's Afghanistan with the cities of Balch , Termiz , Herat and Ghazni - had been conquered. In 1217 ad-Din Muhammad regained Persian Iraq, also subjugating the Atabegs of Fars , the Salghurids and the Atabegs of Azerbaijan . In addition, the Nasrid rulers of Sistan had to recognize the suzerainty of the Anushteginids. The empire of the Khorezm Shahs finally included the entire Iranian highlands , Transoxania and present-day Afghanistan . The Khorezm Shah even felt powerful enough to enter into an open conflict with the Abbasid Caliph an-Nasir .

Downfall at the start of the Mongol Storm

From 1219 the Mongols, united by Genghis Khan, invaded western Central Asia , with metropolises like Samarqand, Bukhara, Merw and Nishapur being destroyed. Muhammad's son Jalal ad-Din offered resistance from Azerbaijan, but was initially defeated by the allied Rum Seljuks and Ayyubids in the battle of Yassı Çemen near Erzincan in August 1230 and murdered a year later.

Mongol invasion

The Mongols had invaded Anatolia in the 1230s and killed Kai Kobad I , Sultan of the Rum Seljuks . After 1241, under Baiju , they began to conquer further areas of the Middle East from Azerbaijan . Together with Georgian and Armenian forces, they conquered Erzurum in 1242 . The Seljuk Sultan Kai Chosrau II was defeated by the Mongols in the battle of the Köse Dağ .

The Mongolian Khan Möngke commissioned his brother Hülegü with another campaign in the west. In 1255 he reached Transoxania . On December 20, 1256, Hülegü captured the assassin fortress Alamut , north of Qazvin . In 1258 the Mongols conquered Baghdad and ended the rule of the last Abbasid caliph Al-Musta'sim . In January 1260 the Mongols conquered Aleppo and Homs . After the death of Great Khan Möngke on August 12, 1258, Hülegü withdrew to Central Asia with most of the Mongolian army. The troops remaining in Syria under the general Kitbukha could still take Damascus and subjugate the last sultan of Syria from the Ayyubid dynasty , an-Nasir Yusuf . However, they were still subject to the Mamluks of Egypt in September at the Battle of ʿAin Jalūt , and again in December 1260 when a coalition of the Ayyubid emirs of Homs and Hama defeated them in the Battle of Homs. From then on, the Euphrates formed the border with the Mamluk Sultanate.

Ilchanat (1256-1335)

After the death of Great Khan Möngke in 1258, independent Mongolian states emerged in China and Iran. During his rule, the increased income from agriculture and trade had shifted the balance of power between the steppe people and the settlers, so that central rule was more difficult to maintain. Hülegü used the power struggle between his brothers Arigkbugha Khan in Mongolia and Kublai Khan in China in his favor. In 1269 Kublai Khan appointed Hülegü as the official ruler of the Mongolian Middle East under the title Ilchan. Thus, in addition to the Golden Horde , the Mongolian China of the Yuan Dynasty and the Chagatai Khanate , another Mongolian-ruled empire emerged.

Alliances

Hülegü first had to deal with Berke Khan , under whom an army of the Golden Horde had advanced into the Caucasus at the end of 1261. In 1262 Hülegü Berke struck back and was thus able to maintain his rule over northwestern Persia. Merke had converted to Islam and now formed an alliance with the Mamluks . The Mongols had been in diplomatic contact with the Pope and European rulers for a while; In 1262 Hülegü sent an embassy to the court of the French King Louis IX. and proposed an alliance against the Mailuks. The two opposing alliances continued throughout the rule of the Ilkhan. Hülegü also had to pacify revolts within his empire. In 1262 he conquered Mosul and put an end to the local Zengid dynasty under the Atabeg of Mosul.

Challenges, conversion to Islam