Economic history of the Ottoman Empire

The economic history of the Ottoman Empire describes the economic development and the interrelated structures of the Ottoman Empire , which existed from its establishment in 1299 to the proclamation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923. The Ottoman Empire, which stretched from the Balkans and the Black Sea region across what is now the Middle East and the North African coast, shows characteristics of a medieval and early modern "world economy" due to the enormous extent and scope of its internal trade. For more than six hundred years the empire lay at the intersection of intercontinental long-distance trade routes. During this time, political, administrative and economic relations within the empire were subject to constant change, as did its relations with the neighboring regions of the world, the Far East, South Asia and Western Europe. In addition to the political ones, it was above all the economic relations between Western Europe and the Ottoman Empire that shaped the history of the two regions of the world, which are closely intertwined, especially in the Mediterranean.

Since the end of the 14th century, the Ottoman Empire increasingly controlled the “horizontal” (east-west) trade route in the Mediterranean, via which goods from Arabia and India reached Venice and Genoa; From around 1400 the “vertical” trade route also led from south to north via Damascus , Bursa , Akkerman and Lwów through Ottoman territory, which brought long-distance trade in spices, silk and cotton products under Ottoman control. The first access of Western European trade organizations to the Ottoman market opened up in the Levant trade from the 16th to the early 18th centuries. The economic power of Western Europe, which continued to increase with the beginning of the industrial revolution , gradually led to a quasi- colonial dominance of the Western economy and to the decline of the Ottoman economy in the course of the 19th century. In the middle of the 20th century, the Republic of Turkey was politically and economically one of the countries of the Third World .

Despite the decline in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the economic history of the Ottoman Empire is characterized by considerable adaptation efforts that have only become the subject of research in the last few decades and are now one of the reasons for the unusually long existence of one in world history great empire.

historical overview

14th to 16th century

The Ottoman Empire emerged at the beginning of the 14th century as Beylik in northwestern Anatolia from the collapse of the rule of the Mongolian Ilkhan . Conveniently located on old trade routes between Asia and Europe, its economy was integrated from the start into east-west trade, the exchange of raw materials, goods and precious metals. Its neighboring countries, the Byzantine Empire , the Islamic countries on the Mediterranean coast and the Persian Empire , had highly developed economic and monetary systems. The expanding Ottoman Empire thus had economic strength and the potential to use it early on. This favored his military and political successes in the following centuries. Numismatic analyzes of the earliest Ottoman coinage show a close relationship to the coins of the Ilkhan and neighboring Anatolian Beyliks, which - in contrast to the records of Ottoman chroniclers - indicates close economic ties between the regions of western and central Anatolia and the continuation of the west-eastern trade route . With the conquest of Bursa in 1326, an important trading center on the Silk Road came under Ottoman rule. After the collapse of Mongolian rule in Persia, the focus of trade shifted from southern to western Anatolia. Trade via the Aegean ports also continued after the Ottoman conquest.

With the conquest of Rumelia from 1435 and the capture of Constantinople in 1453, a new self-image of the Ottoman Empire developed as a great power and heir to both the Byzantine Empire and the tradition of Islam . During his long reign (1444–1446 and 1451–1481), Sultan Mehmed II carried out reforms that made the empire an administratively and economically centralized and interventionist state. Promoting trade and gaining control of trade routes was a major goal of Ottoman policy in the eastern Mediterranean. This brought the empire into conflict with the leading trading and sea power up to that point, the Republic of Venice . The First Ottoman-Venetian War (1463 to 1479) ended with territorial losses and the tribute obligation of Venice.

The growing importance of the empire in Mediterranean trade required the introduction of a generally recognized means of payment. In 1477/78 the Ottoman Empire minted a gold coin, the Altun, for the first time . Franz Babinger suspected that the gold captured during the conquest of Constantinople was used to mint these coins, as the empire did not have any significant gold deposits of its own until the conquest of the Novo Brdo mines .

Mehmed II disempowered the local aristocratic families by either giving them non-hereditary fiefs ( tīmār ) or by replacing them with state and military officials who were directly subordinate to him as “serfs” (ḳul) . Religious foundations ( evḳāf ) were withdrawn and converted into Tımarlehen. Free property (mülk) was nationalized primarily when it was particularly important for the supply of the military. For example, all land on which rice was grown was transferred to state ownership (miri) , since rice was particularly suitable as provisions for campaigns due to its durability.

The silver content of Akçe had remained largely constant until the middle of the 15th century . The coin was minted from 1.15 to 1.20 grams of pure silver (tam ayar) . In the years 1444, 1451, 1460/61, 1470/71, 1475/76 and 1481 the Akçe was repeated in the course of "coin renewals " (tecdid-i sikke) , comparable to the Western European practice of denying coins , by reducing the number of coins used used amount of silver devalued. The old coins were confiscated, their own officials (yasakçı ḳul) were given the task of looking for old coins and buying them for a fraction of their market value. Against the background of the general silver shortage in Europe in the 15th century, the amount of coins was increased by this measure, but the short-term profits for the treasury and the promotion of trade by increasing the amount of money in circulation were quickly wiped out by the parallel rising prices . In addition, the devaluations associated with a visible reduction in the size of the coins led to the first revolt of the Janissaries , who were paid cash in silver coins as early as 1444 , who successfully fought for a pay increase for the first time and repeatedly triggered political unrest in the course of later history.

The military expansion of the Ottoman Empire found its limits in the wars with the powerful neighboring empires, the Habsburg and Persian empires. With the advent of new technologies such as firearms and the introduction of standing, cash-paid armies, warfare became increasingly costly; in spite of all efforts, the result was only the territorial status quo. Land gains, which had opened up new sources of income for the state treasury at the beginning of the Ottoman expansion, now failed to materialize. With the conquest of the Arab heartlands and increasing Islamization, the majority of the population shifted towards Sunni Islam . This was accompanied by a decrease in the pragmatic religious tolerance that had acted as an integrating factor in early Ottoman society. At the same time, under Suleyman II, Islam developed into an instrument of the raison d'être and legitimization of the sultan's rule.

Land and tax registers (defter) , which listed the taxation of the sanjaks according to type and amount, have been preserved from the time of Mehmed II. Under his successor, Bayezid II, the defter (kanunnāme) supplemented the law books , which specified the type of taxation, the time and procedure for collecting them, and the legal relationship between the Tımar owner and the taxpayer. With each new version of the sanjak, the kanunnāme were also adjusted. Under Suleyman I , the Kazasker and later Sheikh al-Islām Mehmed Ebussuud Efendi created a kanunnāme that was valid throughout the empire and , among other things, regulated the relations between the Sipahi and the rural population. Ebussuud derived Ottoman tax law from Islamic law according to the Hanafi school of law : He justified the need for state property with the preservation of property to which all Muslims are entitled and defined the two most important Ottoman taxes, state tax (çift resmi) and tithing (aşar) , according to the Hanafi terms of the charaj muwazzaf (fixed annual land tax) and the charaj muqasama (harvest tax). By equating the aşar with the charaj muqasama , the amount of which was set by the ruler, Ebussuud provided the justification for increasing taxes beyond the “tithe” and thus increasing the revenue of the state treasury. This set of laws (kanun) developed into a secular code of law of the Ottoman Empire , which is different from the Sharia . In terms of title and taxation of state-owned land (miri) , it remained in effect until the end of the empire.

The financial burden caused by the ongoing wars led to decisive changes in the political structure of the empire: The leasing of tax rights created a largely autonomous new elite with the Tımār owners and tax tenants, whose members also worked as producers and traders. In many cases they supported the Sultan, for example in his conflicts with the Janissaries and the ʿUlamā ', at the same time they pushed through their own political ideas against the central administration. The functions of the state that had been centrally controlled up to that point were increasingly being transferred to regional actors, who gained so much influence and independence from the Sublime Porte.

17th and 18th centuries

With Mustafa I. (r. 1617–1618 and 1622–1623), Osman II. (R. 1618–1622), Murad IV. (R. 1623–1640) and İbrahim “the madman” (r. 1640–1648) weaker sultans succeeded one another. At times, strong women, especially the sultan's mothers ( Valide Sultan ), had influence over the affairs of government during the so-called “ women's rule ”. After 1656, Grand Vizier Köprülü Mehmed Pascha (around 1580–1661) and his successor son Köprülü Fâzıl Ahmed Pascha (1635–1676) strengthened the position of the central government. As part of the “Köprülü restoration” named after them, they implemented cost-cutting measures, reduced the tax burden and took action against illegal tax collection. They succeeded in temporarily calming the revolts that broke out by the Janissaries and political factions. The military remained a factor of political unrest, both in the capital (1703 the janissaries dethroned Sultan Mustafa II. ) And in the provinces, such as the Celali uprisings of 1595–1610, 1654–1655 and 1658–1659, the Canbulad rebellion to 1607 or show the Ma'noğlu Fahreddin Pasha's rebellion from 1613 to 1635. Conflicts between the provincial governors and the government in Istanbul broke out repeatedly during the 17th century. In terms of foreign policy, this period is characterized by long and costly wars with the Habsburg Monarchy in the Turkish Wars up to 1699, and with the Persian Empire in the war with the Safavids (1623–1639) .

After the peace treaty of Passarowitz (1718), the Ottoman state was able to better control the trade routes in Anatolia and Syria, which had remained unprotected due to the concentration of the military in the Balkans during the Venetian-Austrian Turkish War . In the period from 1720 to 1765, trade expanded in both the Ottoman Empire and Western Europe. The production of silk and printed cotton fabrics picked up and new craft centers were founded. Much of the production was sold on the Ottoman domestic market; It was not until around 1750 that the Aegean region found connection to international trade. The importation of goods from abroad did not always lead to a reduction in domestic export production; however, since then the Ottomans' production and trade have been more exposed to fluctuations in international trade.

The question remains why the long and difficult wars of the 17th century did not lead to a revival of the economy in the empire itself, since there was a great demand for arms and supplies. The central government's pricing policy is seen as a possible cause, forcing producers to sell their goods to the authorities below production costs or even to deliver them for free in the sense of a tax liability. This resulted in continued loss of capital and, in the long term, a weakening of the economy. In the second half of the 18th century, the costs of war were so high that tax income could no longer cover them. The complex supply system of the Ottoman military collapsed. It was precisely at this time that the (fifth) Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774) broke out. The financially exhausted empire had nothing to oppose to the Russian resources.

19th century

Towards the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century, the rulers in the provinces (ayan or derebey) acted largely autonomously vis-à-vis the central government. In 1808 their political influence reached a climax with the signing of the Sened-i ittifak under Grand Vizier Alemdar Mustafa Pasha . The ayan and derebey acted de facto as local ruling dynasties with considerable military power, the sultan's authority was limited to Istanbul and its surroundings. Above all, the Balkan provinces, with their large estates and commercial enterprises that were created after the abolition of the Tımar system, benefited from a better connection to the world market and from the more loose control by the central government. Pamuk suspects that it is therefore no coincidence that the political collapse of the Ottoman Empire began in these provinces with the Greek Revolution of 1821, the Serbian independence movement, and Muhammad Ali Pasha's striving for autonomy . The administration reacted under Sultan Mahmud II. (R. 1808-1839) to the disintegration of the political order with the abolition of the Janissary Corps in 1826 and the Tımar system (1833 / 1834-1844).

The Iltizam system was formally abolished under Abdülmecid I. (reigned 1839–1861) . The Tanzimat reforms from 1839 envisaged a new centralization of administration and finance as well as a liberalization of the economy. While it would have been in the interests of the large landowners and merchants to catch up with the developing capitalist world market as quickly as possible , the government had retained the upper hand and temporarily regained control of the provinces and economic development.

The period from 1820 to the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1853 is marked by the significant expansion of export trade under British rule. In 1838 the empire signed a free trade agreement with Britain, and later with other Western European countries. The production of agricultural primary goods rose especially in the coastal regions, while the import of industrially manufactured goods put handicraft production there under pressure. In the mid-1870s the share of long-distance trade was only 6–8% of total and 12–15% of agricultural production. From around 1850 onwards, more and more outside capital flowed into the country in the form of government bonds and direct investments. Until the national bankruptcy in 1876, the Ottoman state took out more new loans on unfavorable terms than it serviced old debts. The majority of the borrowed money was used to purchase foreign armaments and consumer goods, which increased the foreign trade deficit. Under European pressure, the Ottoman Bank , which was run by a London consortium and later with French participation, was given a monopoly on the issue of paper money. This tied the Ottoman currency to the gold standard . Foreigners have been able to acquire agricultural land in the empire since 1866.

The last quarter of the 19th century was marked by extraordinary political, social and economic crises. In 1873–4 there was a severe famine in Anatolia. In 1876 the Reich declared bankruptcy and had to agree to European debt management . The Russo-Ottoman War (1877–1878) and the Balkan Crisis were associated with extremely high costs. The wars withdrew large parts of the male working population from production and reduced much-needed tax revenue. The loss of the economically strong European provinces with the peace of San Stefano and the Berlin Congress weakened the economy further. The growing proportion of cheap American agricultural goods in world trade, imported under the terms of the Free Trade Agreement, put pressure on Ottoman producers and reduced national incomes. Under the European debt administration, there were further capital outflows that were used to service the foreign debt. The economy stagnated. With the political and economic rise of the German Empire , the balance of European powers changed. The Pax Britannica was replaced by the struggle of Britain, France and the German Empire for spheres of influence not only in the Middle East. By building railways such as the Baghdad and Hejaz Railway and the Suez Canal , the Western European states divided the empire into their own spheres of influence. Direct investments from abroad thus served more to link the empire to world trade than to expand and modernize its own economy.

Until the First World War

The empire, militarily and politically weakened by the wars and territorial losses in the 19th century, had to restore its strength in order not to be divided between Russia and the European nation-states. From 1903 onwards, more and more foreign loans were taken up, which strengthened the political and economic influence of the donor countries on the Reich. After the revolution of the Young Turks in 1908, fiscal income rose significantly due to more efficient tax collection, but could not cover simultaneous spending, and the deficit continued to widen. After 1910, the Ottoman Empire was so integrated into the capitalist world economy that its various regions can be seen as part of different spheres of influence in European centers rather than as an economically independent area.

population

population

The total population of the Ottoman Empire is estimated at 12 or 12.5 million people for 1520–1535. At the time of its greatest spatial expansion towards the end of the 16th century - although the uncertainty is enormous - perhaps 22 to 35 million people lived in the Ottoman Empire. The population density increased sharply between 1580 and 1620 . In contrast to the Western and Eastern European countries, which experienced strong population growth after 1800, the population in the Ottoman Empire remained almost constant at 25 to 32 million. In 1906, around 20–21 million people lived in the imperial territory (which was reduced by the loss of territory in the 19th century).

Social order

Similar to the time of the Arab expansion in the 7th and 8th centuries, a Muslim minority ruled over a non-Muslim majority in the Ottoman Empire from the 14th to the 16th centuries. During the 14th century, the sultan usually first concluded an equal alliance with neighboring countries, often underpinned by marriage diplomacy. As the empire grew in strength, the allied states became satellite states . Their rulers, whether Byzantine princes, Bulgarian or Serbian kings or local tribal chiefs, retained their position, but owed the sultan loyalty, tribute and support. In this way, towards the end of the 14th century, the Byzantine emperors, Serbian and Bulgarian princes as well as the Beys of Karaman had become tributaries or vassals of the Ottoman ruler. In 1453 Sultan Mehmed II completed this process with the conquest and destruction of the Byzantine Empire and brought the remaining Anatolian Beyliks under his direct rule. In the early 16th century, the Ottomans did the same with the Kingdom of Hungary , initially treating it as a vassal state and finally annexing it after the Battle of Mohács (1526) . The sultans exercised their rule of Istanbul as the center according to a model whose organization is comparable to the modern hub-spoke model . In a pragmatic way, the state mostly integrated the elites of the conquered countries, included them as civil servants in the administration, and tolerated and protected non-Islamic religions under the conditions of Islamic law. The principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia as well as Transylvania were obliged to pay tribute and military successes towards the gate until 1710 , Ottoman garrisons were never used in Transylvania, and mosques were not built in these principalities either. Between 1475 and 1774 the khanate of Crimea was also subject to tribute; its rulers were considered to be the successors of the sultans in the event that the Ottoman ruling family died out.

In the course of the 15th and 16th centuries, the empire saw itself as a great power and dominant protective power in the Islamic world. From this time it was patrimonial as a sultanate and organized as an order of estates , Islamic in its values and ideals, shaped according to the idea of a vast household with the sultan at its head. The social order followed military principles: the Askerî elite comprised the non-taxable members of the Ottoman army (seyfiye) , court officials (mülkiye) , tax collectors (kalemiye) and the spiritual elite of the ʿUlama ' . Socially below the Askerî was the taxable Reâyâ . The upper echelons of the military and administration were considered direct subjects (ḳul) of the sultan, which placed them under his direct jurisdiction and thus strengthened his rule. However, their privileges did not apply to members of the lower classes in military service. The social history of the Ottoman Empire is marked by the efforts of the Reâyâ for social advancement. After the 17th century, the Sublime Porte increasingly lost its influence in the provinces. The Sultan had largely lost its direct political influence, but continued to give legitimacy to the rule . Local rulers ( ayan or derebey ) acted practically independently of the central government. With its reforms since the beginning of the 19th century, the government tried to liberalize the administration and economy on the one hand, and to subject it again to central control on the other.

The Islamic aliens law ( Siyar ) regulated the status of the non-Muslim imperial population. Until the introduction of the Tanzimat reforms in 1839, Jewish and Christian residents enjoyed protection as dhimmi . In exchange for religious and political independence, they had to accept a social status that was subordinate to Muslims. In the Millet system, each community only interacted with the center; officially there were no political connections between the individual communities. The Hohe Pforte acted in the game of interests with flexibility and pragmatism, comparable to a broker. The boundaries between the individual communities were partially permeable, for example at different times and in different regions the conversion to Islam was connected with tax breaks; the institution of boy reading gave Christian young people access to the elite class of the Janissaries.

Non-Muslims who stayed temporarily in Islamic countries could be granted protection as “ Musta'min ” according to Islamic law . The status of foreign merchants who stayed in the Ottoman Empire for a short or long period as non-Muslim subjects of foreign rulers had to be defined in international Islamic law with the rise of long-distance trade. They were finally given a legal status comparable to that of Musta'min , which was confirmed in privileges, the surrenders , which were issued by the Sultan and had to be renewed again and again .

Population migration

The history of the Ottoman Empire is characterized by extensive migrations within its population. Immigrants were especially welcomed if they brought with them contacts, knowledge or manual skills that could be useful to the empire. The Alhambra Edict of 1492 expelled many Sephardic Jews from Spain, and after 1496/97 also from Portugal. They found refuge in the Ottoman Empire, where they were welcomed by a decree of Sultan Bayezid II . They brought printing to Istanbul for the first time; but this could not prevail in the oral and handwritten tradition of the empire and only gained importance again in the early 19th century.

The empire also took in refugees from the Russian-conquered Balkan regions, Circassians and from the Crimea . Shepherd nomads, mostly Turkmens , Kurds or Arabs , migrated to Western Anatolia and Cyprus, the Aegean Islands or the Balkans in search of better pastureland or under the pressure of stronger nomad groups. Political and social unrest such as population pressure in certain regions, or the Celali uprisings of the 16th and 17th centuries, triggered massive population shifts. Last but not least, the empire pursued a policy of active deportations in order to get rid of unpleasant parts of the population or to repopulate an area that was important for the state. At the beginning of the 18th century, Muslim Bosnians from Hungary were on the run back to Bosnia. At the same time, the Ottoman administration sought to push Turkmen and Kurdish nomads to the Syrian border, where they were to be settled as a counterweight to the Bedouins , who increasingly immigrated to Syria in the 18th century. With every war against Western Europe after 1699, Serbian refugees poured into the empire in large numbers; the wars in the Balkans were accompanied by devastating epidemics and famines, which reduced the population. The settlement of Albanian mercenaries on the Morea led to the flight of parts of the Greek population at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century. The Ottoman administration repopulated these areas with Anatolian settlers, a temporary exemption from land tax (charaj) served as an incentive .

The beginning of the 19th century was marked by a pronounced rural exodus. Contemporary Western European observers such as the French Consul General de Beaujour report that in Macedonia there were only two rural residents for every city. At the same time, the Western European population was divided between urban and rural areas at a ratio of 1: 5-6. De Beaujour cites the repression and exploitative taxation by local rulers as the reason for the rural exodus. Famine and natural disasters reduced the population in many parts of the country in the 18th century.

In the 19th century, the Ottoman state tried to reform itself using the administrative means of the nation state . In the conflict between the Enlightenment, Islamic and Turkish nationalist schools of thought, the cohesion of the various religious and ethnic groups and ultimately the empire itself broke. The political dominance of the Young Turks led to a nationalist redefinition of citizenship and ultimately to emigration, deportation and genocide of groups who had been part of Ottoman society for centuries. In the 20th century, the 1915 Deportation Act triggered a resettlement campaign that ultimately led to the genocide of the Armenians ; The Greek population, who had lived in Asia Minor since ancient times, was also forced to emigrate from 1914 to 1923 .

Land ownership

Newly conquered regions were initially administered as a province ( Sandschak , Turkish sancak ), the local rulers were either eliminated or incorporated into the administration as civil servants.

If an area came under direct Ottoman control, this initially meant an immediate economic advantage for the population: With the dwindling influence of the Byzantine Empire, many areas came under the rule of local princes or monasteries, who had imposed very high taxes on them; In contrast, the Ottoman tax burden was less oppressive. After the annexation, Ottoman officials first made a detailed record of all taxable resources in the region and recorded the information in detailed account books ("Tahrir defterleri ") . Population registers ("tapu tahrir" ) documented taxable heads of households and men fit for military service. In Ottoman studies , Tahrir and Defter are important but incomplete sources for analyzing population development: Since only directly taxable persons (mostly men or widowed women) were registered, the number of people actually living in a household (hane) remains unclear. The size of the non-Muslim population can only be inferred indirectly from the emergence of the jizya . Since the majority of women in the Ottoman Empire did not pay taxes, the tahrir registers are mostly silent about them.

After the inventory of a region, its tax income was given to members of the military and the administration in the form of tax loans ( Tımār ) . The fiefdoms (timariots) were allowed to raise taxes in the area assigned to them. The more important the fiefdom was for the state, the higher the allocated income. The size of a tax loan was dependent on its productive power. The more fertile a region, the smaller the individual tımār could be.

Agriculture was the basis and most important source of economic value creation. The land was basically owned by the state. Hereditary private real estate (garbage) never made up more than 5 - 10% of the total area. Another part of the property was held by the pious foundations (vakıf) . The state property (arz-i miri) was administered by the tax authorities and granted in the form of benefices to members of the military, the Sipahi , as well as to civil servants who received their income from it. The benefices were given by the Sultan or his administration, were not hereditary and could neither be sold nor given away. The land allocation was documented in the form of land documents (sınır-nāme) . Depending on the expected yield of the country, a distinction was made between state domains, staff sprouts (has) of high dignitaries such as viziers, companionship and sandschakbegs with a yield of at least 100,000 Akçe, large pfrances (ziamet) of officials and senior officers (over 20,000 Akçe) and small pfrances (tımar ) with a yield of 1,000–2,000 acres. As a state domain (has-i hümayun), part of the land ownership always remained state property, the taxes of which were mostly collected from tax tenants (mültezim) . They had to deliver a fee (mukataa) that had been determined beforehand on the basis of the expected yield . Mültezim could also set additional taxes and thus enrich themselves. Therefore, tax leases were in great demand, and they were often given to the highest bidder. The peasantry was not serfs and was mostly not under the jurisdiction of the Tımar owner, but they were obliged to cultivate the land. In addition to the farmers, slaves also worked in agriculture.

| Legal status | description |

|---|---|

| State property (Miri) | Tapulu: Contractually (tapu) agreed land ownership, hereditary, requires special benefits to the Tımar owner or the state. Basis of the Çift-Hane system |

| Mukataalu : simple lease against annual payment; often uncultivated land thatcan be convertedintotapuluafter reclamation. | |

| Free property (Mülk) | As a gift from the sultan from miri |

| from reclaimed wasteland | |

| land acquired by purchase contract under Islamic law | |

| Land holdings from before the Ottoman conquest, confirmed by the Sultan's privilege. | |

| Vakıf | Property owned by religious foundations, monitored by the state, tax-exempt, often managed by members of the founding family |

| Mevat | Wasteland, never cultivated or abandoned and overgrown. Reclamation of such land brings property rights (mülk) . |

| Legal status | description |

|---|---|

| Imperial domain (hass- ʾi hümāyūn) | Income from the domain goes directly to the state treasury. |

| Domain (hate) | Domain of a dignitary ( vizier , beg ); Registered income over 100,000 Akçe |

| Ziamet | Estates of lower military commanders ( subaşı or zaim ) of the Tımar armed forces in the provinces; Income 20–100,000 Akçe |

| Tımar ordirlik | Rural estates allocated to the Sipahi , an average of 1,000 in the 15th century and 2,000 in the 17th century. Several Tımar were administratively combined in sanjaks . |

| Mevkuf | Tımar without an owner in state custody. Until the new allocation to a Sipahi, the tax income flowed directly to the treasury. |

| Arpalık, paşmaklık, özengilık, etc. | Goods that are not used for the maintenance of the military, but have been allocated to members of the elite for their maintenance. |

agricultural economics

In its origins, the Ottoman Empire was an agricultural economy with a labor shortage, large, fertile tracts of land, but limited capital resources. On average, around 40% of the tax revenue from small family businesses was raised directly or indirectly through export taxes. Larger estates were more likely to emerge in newly populated or newly cultivated regions, mainly as a result of the settlement of refugees and nomads by the Ottoman government. Characteristic for the village settlements was their connection with the larger cities nearby and their bureaucratic organization in control units ( Çift-Hane ) . The money economy was also developed early in the Ottoman Empire. After Inalcik the economic organization of these small family farms can most likely with the post-Marxist theories Chaianov describe.

Agriculture not only produced raw materials from direct cultivation for its own use and export, but also processed them further. The goods were sold in local markets or to intermediaries. As early as the 17th century, the state administration was promoting the production of crops and livestock for the production of milk, meat and wool through tax and inheritance laws. The organization of agriculture continued into the 20th century. The increasing demand for agricultural raw materials from European countries and the increasing commercial export in the 18th century led to an increase in agricultural production. In the 19th century the government tried harder to settle the nomad population and thereby make it more politically and economically controllable. With the population growth in the cities, new domestic markets emerged. The increase in production in the agricultural sector was based on irrigation projects, improved cultivation methods and the increasing use of modern agricultural machinery, so that more production areas could be made usable and cultivated. The authorities resettled refugees and displaced persons in small plots, particularly in the previously sparsely populated regions of the Anatolian highlands and the steppe zones of the Syrian province. Agricultural reforms in the late 19th century led to the establishment of agricultural schools and model farms, as well as the emergence of a bureaucracy of agricultural specialists who increased the export of agricultural goods. Between 1876 and 1908, the value of goods exported from Asia Minor alone increased by 45%, while tax revenues increased by 79%.

Production processes

Manpower

slaves

Slavery was an important economic and political factor in the Ottoman Empire. Prisoners of war as well as the inhabitants of conquered areas of the Balkans, today's Hungary or Romania were enslaved. To secure newly conquered areas, the indigenous population was occasionally sold on the slave markets and replaced by forcibly resettled residents from other regions of the empire. Galley slaves were used by almost all sea powers in the Mediterranean, on the ships of the Italian states of Genoa and Venice , Spain and France as well as on the galleys of the Ottoman Empire. Originally, the Janissaries were recruited from the enslaved population and in the course of the boy harvest . After their conversion to Islam, they received a thorough training that qualified them for work in the Ottoman administration and thus enabled them to advance socially.

In 1854/55 the slave trade in the Ottoman Empire was banned by an edict under pressure from the major European powers. Protests by traders in the Hejaz , who citing an Islamic legal opinion ( fatwa ) sparked an anti-Ottoman uprising, led to a further decree in 1857 that exempted the Hejaz from the prohibition of slavery.

Nomads

The nomadic population was essential to the Ottoman economy. It was organized and registered by the authorities for taxation according to family units , each of which was assigned a yurt made up of land for summer (yaylak) and winter pastures (kışlak) . In addition to keeping cattle, nomad families also cultivated cotton and rice in the winter pasture areas. As early as the middle of the 14th century, the Turkmen tribes of western Anatolia were growing cotton, which was exported to Italy via the ports of Ephesus (Ayasoluk), Balat (Istanbul) or the island of Chios . Around 1340 wheat, rice, wax, hemp, oak galls, alum, opium, madder root, oak wood and “Turkish silk” are documented as export goods. Western trade archives list wheat, dried fruits, horses, cattle, sheep, slaves, wax, leather and alum as imports, wine, soap and fabrics as exports. Carpet manufacture in the Uşak, Gördes and Kula Basin areas received both wool and labor from the Turkmen nomadic population of the surrounding mountains. From the 14th to the 20th century, wool and animal skins were among the most important export goods from Anatolia. Nomadic camel breeding was of particular economic importance. Camels are twice as resilient as horses or mules and can carry around 250 kg. Until the advent of modern means of transport in the 19th century, camel caravans were the most important means of transport in overland trade. The army also depended on camels and nomadic camel drivers for the transport of provisions and heavy equipment.

Urban artisans

Compared to agriculture, which provides tax income, artisanal production in the cities was of less importance for the Ottoman administration and is accordingly sparsely documented. Craftsmen were able to purchase the raw materials they needed for their work either directly from the village and nomadic population at trade fairs (panayır) near the summer camps, in exchange for trade goods, or through the central purchasing department of the craft guilds. In the cities, artisans mostly worked in small shops or several in workshops that were often rented from a Vakıf Foundation. The foundations had started to invest in buildings because of the high inflation during the 17th century. Usually several workshops that produced the same product were grouped together in “craft streets ” (çarşı) . Several craftsmen were able to form partnerships (şirket) and, for example, make major investments together. The manufacture of elaborate products such as silk fabrics, in which different specialists had to work together, could be controlled by a single trader who bought the raw materials, monitored the individual production steps and finally brought the finished product to market. Such production networks also included surrounding villages. According to Faroqhi, however, the mode of production does not seem to have corresponded to that of a typical proto-industrialization , since the village population carried out production alongside agriculture. The decentralization of production in villages also made it possible for women to do handicrafts from home . Since around the 18th century, practicing a craft in a certain place, for example a foundation building, was dependent on a type of license or hereditary place, the gedik . This procedure increased the social control of the handicrafts at the price of restricted mobility of the workers.

Free labor

While slaves still worked predominantly in the urban factories of the 16th century, in the 17th century producers switched to employing free workers who were available in the growing cities and willing to work at low wages. Women made up a large proportion of these workers. Often the production was done at home , which enabled women in particular to contribute to the family income. In the factories, men and women worked together - differently from region to region - and members of all ethnic groups took part in production.

Craft guilds

|

|

|

|

Left picture : Parade of glassblowers.

Right picture : Parade of architects from Surname-i Hümayun , approx. 1583–1588 |

||

In the cities, the handicraft was organized in guilds (esnaf) , which were roughly comparable to the European guilds . However, the structure of the Ottoman guild system was more complicated; Within a product group, several guilds with official approval were only responsible for one specific product type. An important task of the guild overseers (kethüda) was the acquisition and distribution of raw materials. The guilds enforced the prices set in official registers (narh defterli) and checked the quality, size and weight of goods. The aim of the official measures, comparable to an early central administration economy, was to supply the inhabitants, especially of the capital Istanbul, with food and goods. The center of the city's handicrafts was the bazaar . The guilds were originally headed by leaders (şeyh) who had religious prestige. In the course of time, the kethüda and yiğitbası (leaders of non-Muslim guilds) mostly played their roles. Kethüda had to apply for their office in an official process and were appointed by a document (buyuruldu) from the Grand Vizier, which instructed the typing office (nakkaşhāne) to issue the certificate of appointment. The guilds and the bazaar trade were monitored by officially appointed market overseers ( muhtasib ) .

The Ottoman authorities also used the guilds to control the urban population at a time when no police were known. They ensured the payment of taxes and duties; the army also made use of guilds: guilds were recruited for every campaign to equip the army. As long as the Ottoman Navy needed rowers for its galleys - well into the 17th century , the ranks of row slaves and convicts condemned to galley service were replenished with the help of guilds by free rowers, and shipbuilders obliged to pay officially fixed low wages. Since the 17th century, craftsmen increasingly committed themselves to service with the military units stationed on site. As members of the Askerî , they were exempt from many taxes and their goods were protected from confiscation. Craft guilds paid protection money to military units by the end of the 17th century at the latest, and members of the military were also able to practice a craft in order to be able to support themselves and their families in the face of inflation and the value of coins. In this way, the commanders of local military corps increased their influence. In the course of the 18th century it was increasingly only the heads of guilds who found such connection to the military, which increased social differences. Since then, craft guilds have set up foundations that lend money against interest. The usual interest rate was 15%. The abolition of the politically influential Janissary Corps in 1826, as well as the Tanzimat reforms since 1839, indirectly led to the decline of the guilds that had lost their protection.

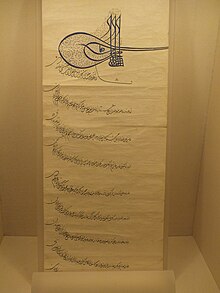

Court manufactories

In the court workshops (Ehl-i Hiref) of the Ottoman sultans, artists and craftsmen of various styles worked. Calligraphy and book illumination were practiced in the scriptorium, the nakkaşhane . The illuminations and ornaments designed there, also under the influence of the Safavid court art, also influenced the patterns of other products of Ottoman art. Besides Istanbul, famous centers of handicrafts were mainly Bursa, Iznik, Kütahya and Uşak. As the “silk city”, Bursa was famous for silk fabrics and brocades, İznik and Kütahya for fine ceramics and tiles, and Uşak especially for carpets. As employees of the court, the artists and artisans were documented in registers, which also provided information on wage payments, special awards from the Sultan, and changes in the artists' salaries. The Court also set prices for individual products in price registers (' narh defter '). In later times the prices set by the court no longer covered the high production costs of the elaborately manufactured products and could no longer compete with the prices that could be achieved in export trade. Complaints from the central administration that the İznik potters would no longer comply with the farm's orders because they were too busy producing mass-produced goods for export are documented. In the economy as a whole, the court manufacturers only played a negligibly small role.

Mechanized production

With hydropower or steam -powered factories were built in the Ottoman Empire until the end of the 19th century. There were hardly any large, capital-intensive factories. The first factories were founded on the initiative of the state under Muhammad Ali Pascha in Egypt and under Mehmed II around Istanbul. From the beginning they were protected by state monopolies; however, their operations were inefficient due to a lack of fuel, spare parts and a trained workforce. They were often poorly managed, as their overseers mostly belonged to the military elite and were not properly qualified. From around 1870 privately run factories came into being, but their production was of little importance in relation to the artisanal businesses. Most were in the Balkan provinces, the cities of Istanbul and Izmir, and in the vicinity of Adana (Southeast Anatolia). The factories in the Balkans and in the capital cities worked mostly for the military, the rest for the needs of the residents. A notable industry emerged in the Turkish Republic only in the 1930s.

Deindustrialization

Pamuk describes two forces that revolutionized the global economy in the 19th century: The global transport revolution with the introduction of railways and steamers integrated the global raw material market. Steam ships could transport more goods, their increasing use lowered transport costs and stimulated trade. Trade between the center and the periphery was booming, raw material prices leveled off within the world markets. The second influencing factor was the increased need for industrial intermediate products, such as Ottoman raw silk and wool, the production of which rose sharply. Exports to Western Europe rose from £ 5.2 million in 1840 to £ 39.4 million in 1913, with annual growth rates of around 3.3%. The highest growth rates were recorded between 1840 and 1873, with the volume of trade doubling every 11 to 13 years. The tonnage of ships in the port of Beirut rose from 40,000 tons (1830) to 600,000 (1890), other ports in the eastern Mediterranean showed similar rates of increase.

As Western European industry increased its production, so did the manufacturing costs and prices for manufactured goods, but the demand for raw materials from the periphery also rose. The increasing per capita income increased the demand for high quality consumer goods from the Ottoman Empire, such as wheat, raisins, and also for opium. Since industrialization has been accompanied by an unbalanced productivity advantage at the expense of a country's agricultural products and natural resource products, the relative price of industrial products fell everywhere, but especially in the countries that had to import them. The revolution in freight transport ensured that the peripheral countries could meet the increasing demand for raw materials. As long as this demand persisted and prices therefore remained high, there was no economic incentive in the Ottoman Empire to build up its own industry.

Finally, the effects of the two influencing factors mentioned subsided. With the establishment of mature industrial production and efficient use of resources, the growth rate, and with it the demand for Ottoman export goods, did not increase any further. The boom in the Ottoman export industry, which was specialized in these needs, which lasted for over a century and was particularly strong in the years 1850–1890, collapsed.

production

According to Quataert , the production of raw materials and goods in the Ottoman Empire is characterized by its stability over several centuries (certain places produced the same or similar goods for centuries) with simultaneous considerable internal dynamics with which production is based on market changes within and outside of the Ottoman Empire responded. With the introduction of new production methods or new products, the Ottoman economy was able to maintain existing markets for a long time or to open up new ones. Similar to agriculture and trade, the dwindling political influence and the loss of trade routes and partners due to the loss of territory in the 19th century also brought production to a standstill.

cotton

Historical centers of cotton production existed in the Levant, Mesopotamia , the shoreline regions of the Aegean and the Thessalian plain and in individual regions of Macedonia . Already in the 11th / 12th In the 19th century, cotton and yarns and fabrics woven from it were traded locally and exported to Europe. Cotton seeds from the Levant were exported to Virginia , Delaware and Louisiana , where they formed the basis for the later cotton industry. Up until the late 18th century, Ottoman cotton production outweighed that of the North American colonies by about 30 times; Raw cotton was both processed in local factories and exported. In the early 20th century, the worldwide increase in textile production led to supply bottlenecks for raw materials. As early as the 19th century, cotton production in Egypt far outweighed that of the Ottoman Empire. While around 100,000 bales were being produced in the 1850s, their number rose to 1.7 million before the outbreak of the First World War.

| Period | region | total | local processing | export |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early 19th century | Salonika | 37,500 | 15,000 | 22,500 |

| 1830s | Adana region | 19,000 | 19,000 | - |

| 1850s | Asia Minor | 50.0000 | 12,500 | 37,500 |

| Macedonia | 9,700 | 4,850 | 4,850 | |

| Thessaly | 3,500 | 3,500 | - | |

| 1879 | Asia Minor | 27,000 | 4,000 | 23,000 |

| 1890s | Osman. Rich overall | 60,000 | ||

| 1904 | Adana, Syria, Western Anatolia | 80,000 | ||

| 1906 | Adana region | 50,000 | ||

| 1940 | Adana region | 250,000 |

Dyes and yarn dyeing

Traditional natural colors are obtained from plants and insects. Until the invention of the first synthetic colors such as 1856 by the English chemist William Henry Perkin first produced Mauvein consisting of was madder gained -Pflanze madder or "Turkish red" a prized commodity for domestic and foreign manufacturers. Madder red was obtained in different regions. The mountain regions of Ereğli south of Konya and the western Anatolian area around Gördes delivered their goods to the factories in Izmir and Aleppo , and from there to Europe. With the advent of synthetic dyes, manufacturers were able to dye their yarns themselves, which led to the decline of the dye industry and a significant decline in the production of natural dyes: While in the early 1860s in Asia Minor there were around 10,000 bales of madder roots worth 12 million each year Turkish piasters were exported, the export value dropped to just 0.4 million piasters in the late 1860s. While Izmir exported 5,000 tons of madder roots in 1830 and 7,000 tons in 1850, between 1905 and 1911 only about 94 tons were exported per year. The declining demand for natural dyes led to the abandonment of the previously extensive colored plant plantations towards the end of the 19th century. The textile manufacturers started to import synthetic dyed yarn from Europe and to process it further. The import of pre-dyed yarn was only restricted when dye works were opened in Izmir at the beginning of the 20th century. In contrast, the craft of blue dyers in Diyarbakır and Aleppo was able to assert itself , as only the indigo imported from India was replaced by the chemically identical synthetic dye.

Wool, cotton and silk fabrics

Silk fabrics

Raw silk and silk fabrics have long been the most important goods in the Levant trade. The main trading center was Aleppo , which obtained silk from Persia through the caravan trade . European middlemen bought the silk and exported it to their countries. Around 1620 90% of the 230 tons of raw silk that Europe consumed during this period came from Aleppo, of which 140 tons were bought from French countries, the rest from Venetian and English countries. Silk made up about 40% of the goods imported from this city. By 1660 England dominated trade with 150 to 200 tons and had largely ousted France and Venice. In the early 18th century, when silk became available from Italy and Bengal, the silk trade in the Levant declined. The increasing European demand for raw silk made Ottoman production more expensive. Ottoman weavers were also restricted by the administration's fixed and low price policy and were unable to adjust their prices to the increased costs. Due to the import of fine, printed Indian cotton fabrics, the demand for silk fabrics decreased both in the empire and in Europe. However, individual trading centers, such as the island of Chios , were able to maintain their position in the trade in silk fabrics. Between 1700 and 1730, mulberry tree plantations and silk worms were raised in the Bursa region; the export of silk fabrics from Bursa remained low until 1815.

Wool fabrics

Ottoman textile production adapted to changing market conditions and produced fabrics that could be sold to the less affluent at a lower price. The inaccessibility of Anatolia and the Balkan provinces may have protected local internal trade from foreign competition. The weavers and traders in the southern Bulgarian town of Plovdiv (Turkish: Filibe) succeeded in building up a trading network that was largely able to operate independently of import competition. The market for woolen fabrics also suffered from the rise in raw material prices as a result of growing European demand. The Sephardic weavers, who settled in Thessaloniki under Bayezid II, manufactured woolen fabrics of medium quality both for trade and for furnishing the Janissary corps. The rising raw material prices as well as the competition from imported English fabrics reduced the sales market. From the end of the 16th century, deliveries to the Janissaries were also collected as a tax. Weavers and traders then left the city and settled in Bursa and Manila, among other places. The Ottoman state had regulated the export of raw materials, but not the import of competing goods. Since the end of the 16th century, the English Levant Company was able to import English cloths into the empire, which they sold at low prices in order to counter-finance the purchase of silk in Aleppo or Izmir. The Ottoman producers were left with the market for coarse woolen fabrics (aba) , such as those woven in Plovdiv.

Cotton fabrics

The manufacture of cotton fabrics faced competition from India in the 17th century. From there, colorfully printed fabrics reached the Ottoman Empire via Jeddah and Basra and the caravan route to Aleppo. Merchants from Cairo also took part in the trade in Indian fabrics, which, along with the coffee trade, was able to compensate for the dwindling importance of the spice trade monopolized by the Dutch East India Company . In Western Anatolia, Syria, the city of Nablus and in the Manisa region, the production of cotton fabrics was able to hold up. Egyptian cotton fabrics were also in demand until the end of the 17th century. The documents of the Chamber of Commerce of Marseille list white cotton fabrics from Izmir , Saida , Cyprus and Rashīd ( “demittes” and “escamittes” ). A cotton fabric of a rather coarse quality was known as "boucassin" ( Turkish bogası ) and came from Izmir. From Aleppo, fabrics dyed blue with indigo and red with madder were exported. Aleppo was able to expand its position in the textile trade with France until the end of the 18th century. The export trade in cotton fabrics only declined with the reintroduction of English cloths after 1815.

According to Ottoman sources, the cities of Mosul in present-day Iraq and Nablus in present-day Palestinian autonomous regions were of particular importance in domestic trade . Other centers were the cities of Malatya , Kahramanmaraş , Gaziantep and Diyarbakır . The employment of workers, especially women, at low wages and the concentration on cheaper, coarser materials to be produced, as well as the relocation of production to smaller towns made the products competitive in the domestic market. Production only started during the general economic decline towards the end of the 18th century under Selim III. to a standstill.

Textile production in the 19th century

Falling raw material prices due to the availability of very cheap North American cotton in Great Britain, changed technologies and fashions as well as the import of machine-spun yarn and synthetic dyes, and later machine-woven fabrics, all influenced Ottoman textile production in the 19th century. The textile industry in the empire reacted to the tough competition in various ways: On the one hand, it increasingly used cotton itself as a raw material instead of wool or silk, and imported machine-spun yarns replaced traditionally hand-spun yarns. The import of cotton yarns and fabrics has risen continuously since 1815 (after the trade barriers due to the continental blockade were removed at the end of the coalition wars ), reaching an estimated 4,100 tons around 1840, and finally around 49,000 tons around 1910. British manufacturers have dominated the cotton fabric market since they replaced Indian cotton fabrics that had been imported into the empire for centuries at the beginning of the 19th century. Other European manufacturers also took part in smaller shares in the market. Hand-spun cotton yarns and fabrics made from them claimed a market share of around 25%.

Ottoman producers were able to secure market niches for themselves in the field of woolen fabric production by producing special goods for certain groups of buyers: In the 19th century, the region around Edirne was an important center of woolen fabric production. Coarser (aba) and finer grades (şayak) were traded on the local market, to Anatolia, and for export. In the Bulgarian sanjaks, the regions around Plovdiv and Salonika , production was sustained and even increased in the late 1880s. From 1840 imported wool yarn was used, after 1880 yarn from Ottoman factories. After 1880, mechanical looms also appeared in the region . Wool weaving was able to hold its own mainly because it concentrated on inexpensive, coarser fabrics that the poorer population could afford and by supplying the military. For comparable reasons - in addition to smaller centers - the woolen fabric manufacture in Gürün was also able to maintain its market position into the 20th century by covering the needs of the nomadic Kurds and Turkmens who went to the markets there. In addition, the production costs and thus the prices fell due to the employment of homeworkers in rural areas and of manufacturing workers, in both cases often women, at very low wages. The inexpensive machine-spun yarn was imported, while hand-spun yarn was still used for special fabric qualities. After the Ottoman manufacturers had better learned how to use the new synthetic dyes, the yarns were dyed on site at low cost. Domestic manufacturers invented new, frequently changing clothing fashions for the market, which made it more difficult for foreign manufacturers to sell their goods because they were slower to adapt to changing demand.

Carpets

Since the Renaissance period , carpets have been one of the best-known export goods to Europe. Oriental carpets have been depicted on Western European paintings since the 14th century and have been the subject of art historical research since the late 19th century. A customs register from Caffa in the Crimea for the period 1487–1491 mentions carpets from Uşak , thus proving the long tradition of carpet production in this region. Records show that carpets were made for the sultan in Uşak to furnish mosques, especially for the Selimiye mosque in Edirne . Carpets have been produced in large quantities for export since the 15th century. Organized trade across the Black Sea and the Danube, and further overland to Western and Northern Europe, began with Sultan Mehmed II's trading privilege from 1456, which granted Moldovan traders the right to trade in Istanbul. The first known document from the Transylvanian city of Brașov relating to the carpet trade was drawn up between 1462 and 1464. Customs registers have been preserved in various cities in Transylvania and show the large number of carpets that reached Europe via this region alone. The Braşov Customs Register from 1503 documents that over 500 carpets from the Ottoman Empire were transported through this city this year alone. English and Dutch merchants also exported Anatolian carpets as luxury goods to Europe, initially through Venetian middlemen. An Istanbul price register (“ narh defter ”) from 1640 already lists ten different types of carpets from Uşak. By the 18th century at the latest, there was an export industry in Western Anatolia.

From around 1825, the mass-produced carpets became affordable for less affluent European families, and from 1840 they were also exported to the USA. In both Europe and North America, wages rose with the spread of industrialization. The income gap between the western world and the Middle East had a favorable effect on Ottoman goods production. The world exhibitions since the 1850s also showed luxury goods from the Ottoman Empire and spurred the interest of Western buyers. Since the 1840s and 1850s, the Ottoman government promoted carpet production in the Uşak and Gördes regions . In the mid-1850s, carpet exports from Izmir totaled 1,096 bales worth 5.7 million piasters, and between 1857 and 1913 production increased eightfold. Similar growth figures are known for the Uşak and Gördes regions, and carpet production expanded to other regions in the early 20th century. Overall, it is estimated that around 1880 in Anatolia around 2,000 looms were producing for commercial use, and by 1906 their number had risen to around 15,000. Quataert assumes that carpet production increased in response to the decline of the silk industry during the decades 1860–1880, partially absorbing the labor that became available there, and partially compensating for the loss of cash income from the silk trade. About 10% of the carpets produced in 1860-1870 were sold in the country itself. The high demand from the western market changed both the traditional carpet patterns and the materials used (not only in the Ottoman Empire, but also, for example, in Persian carpet production ). To meet the raw material requirements, wool and partly also pre-made and dyed yarn were imported from Europe, especially from England. The introduction of synthetic colors in the late 19th century had a fundamental effect on the color and patterning of the knotted carpets.

Carpet production and export have been dominated by Ottoman, European and American trading houses since around 1830, and they continued to expand their leading role in the 19th century. The trading houses expanded carpet production in other regions and made some of the necessary material (such as dyed yarn) available to the knotters , who often worked from home , and changed the traditional pattern design in order to be more successful on the market. The Ottoman government promoted carpet production with sample exhibitions and quality controls as well as the establishment of handicraft schools. This is exemplified for the cities of Konya and Kırşehir . At the beginning of the 20th century, a consortium of European and Ottoman dealers developed the company Oriental Carpet Manufacturers , which in 1912 controlled most of the approximately 12,000 looms in the Konya province and employed around 15–20,000 mostly female weavers. In 1891 the Ottoman court established the Hereke carpet manufacture, which obtained its yarn from a factory in Karamürsel .

Metal extraction

silver

Silver mines were already producing in Eastern Anatolia in Byzantine times; however, access was blocked by other beyliks until the end of the 15th century. The rapid expansion into the Balkan region brought the rich silver mines there under Ottoman control. The mines were brought into state ownership and operated on a tax lease. Laws and ordinances governed the mining operations in detail to meet the growing demand for silver and coins. The most productive mine, Sidrekapsi in Macedonia, employed around 6,000 workers in the 16th century and produced around six tons of silver per year. The annual production from the Balkan mines at this time is estimated at 26-27 tons and rose, according to the tax registers obtained, by 1600 to 50 tons.

gold

Silver and small copper coins were the most important means of payment in everyday trade. In addition to its use in handicrafts, gold in the form of coins was mainly used to transfer large sums of money in trade or to store capital. For this purpose, on the one hand, foreign currencies such as the Venetian ducat (efrenciyye) were used , which were minted in the empire itself with partly reduced precious metal content. From 1477/78 own gold coins were also put into circulation. Until the conquest of the Serbian and Bosnian mines in the 1450s and 1460s, there were no sufficient gold deposits of their own. Larger amounts of gold found their way into the state coffers either from spoils of war such as after the conquest of Constantinople, from ransom such as after the battle of Nicopolis or after the conquest of the Egyptian Mamluk Empire in 1517. In the 16th century, Egypt delivered 500–600,000 gold coins a year to the central financial authority.

Domestic economy

The expansion of the empire and the volume of its domestic economy led Fernand Braudel and the historians of the École des Annales to view the empire as an independent “world economy”. The Annales School, however, assumes that a world economy has only one center. The presence of multiple economic centers is seen as a sign of an underdeveloped or already in decline world economy. In addition, in Braudel’s theory, the state is guided by the needs of trade. Since the Ottoman Empire had several important centers with Istanbul, Aleppo and Cairo, and the government repeatedly intervened in the economy according to its own interests, Suraiya Faroqhi considers Immanuel Wallerstein's concept of the " world system " to be a more appropriate description of the Ottoman economy until the 17th century Century. At that time, individual regions of the empire exported raw materials and individual luxury goods to Western Europe and imported mainly European fabrics. By the turn of the century, the Ottoman Empire was politically and militarily influential enough to largely protect its internal market from European competition. Ottoman traders set up their own networks for handicraft production and distribution of goods, which were able to assert themselves in competition with Europe. In contrast to the detailed records of European merchants, however, hardly any documents from Ottoman traders are known, so that this sector of the Ottoman economy has not yet been adequately researched.

The loss of territory in the late period of the Ottoman Empire interrupted or destroyed the traditional trade routes in the Ottoman internal trade.

Trade with the east

Trade routes

Up until the middle of the 14th century, caravans with trade goods such as spices or silk from India, China and Iran traveled via a northern route to the Black Sea ports of Azov (Tana), Soldajo and Caffa , or via the Iranian cities of Soltaniye and Tabriz to the Anatolian ones Ports of Trabzon , Samsun , Ayas , Antalya and Ephesus . Genoese and Venetian traders established branches in Tabriz and in the port cities mentioned very early on. Genoese ships tended to load Anatolian products such as alum, beeswax, cheese and leather in Trabzon. Until the Ottoman conquest of the Mamluk Empire , the most important trading ports for spices in the Mediterranean were Beirut , which was supplied via the route Jeddah - Mecca - Damascus , and Alexandria , which was supplied via Cairo . The depots of the port of Methoni were supplied with spices from Beirut and Alexandria, which were transported from there by Venetian convoys (muda) to Europe as early as the beginning of the 15th century.

In the course of the 15th century the southern route gained increasing importance, in the Ottoman Empire Bursa gained increasing importance as a trading port for Indian and Arab products and for Persian silk. Goods for the Ottoman trade were also regularly shipped from Alexandria to Antalya. A customs register from 1477 lists fabrics, raw silk, mohair, iron tools, wood and construction timber as the most important export goods, spices, sugar and indigo as import goods. Around 1560, spices and indigo were still being imported via Antalya, but the focus of imports was now on rice (an important provision for the army due to its durability), linen and sugar. Since the poorly forested Arab countries were dependent on wood from the Anatolian Taurus Mountains for their shipbuilding, a state monopoly on the timber trade was established as early as the middle of the 15th century. With the conquest of Rhodes in 1522, the Ottoman Empire had a safe, direct sea route between Istanbul and the Egyptian ports of Alexandria and Damiette , and Antalya lost its importance as a trading port. The most important trade route for goods from India remained the caravan route from Damascus to Bursa and from there to Southeastern and Eastern Europe.

Spice trade with India

The port city of Kalikut and the Sultanate of Gujarat were the traditional Islamic trading centers for spices in India . In 1498, however, the Portuguese Vasco da Gama discovered the sea route to India via the Cape of Good Hope . Portugal thus had direct access to the market for spices, for which Egypt and Venice had previously had a monopoly. A network of bases was established in Portuguese India , the Portuguese India armadas regularly operated between Goa or Cochin and Lisbon. Portuguese ships cruised off the Malabar coast and brought in Indian and Muslim ships, which went from there to the trading ports in the Red Sea. As early as 1502, Venice had warned the Mamluk Sultan of the devastating consequences of Portuguese trade. In 1508 a combined fleet from Egypt and Gujarat, in which Ottoman mercenaries also took part, defeated the Portuguese in front of Chaul , and in 1509 they got the upper hand in the naval battle of Diu .

Control of the sea route in the Red Sea

Portugal tried to control the sea route from Bab al-Mandab and the Gulf of Aden , and thus the sea route into the Red Sea. A trade blockade was not feasible on the high seas. Since 1503 Portuguese fleets have been sent regularly to the Red Sea to build fortifications at strategically important points along the coast. In 1513 the Portuguese conquered and fortified the island of Kamaran and thus gained a base that threatened the trade of the Mamluk Empire directly. This defeat showed that only the Ottoman Empire had the means and capabilities to put a stop to the Portuguese: in 1510 the Mamluk Sultan al-Ghuri asked the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II for support; In 1517 the Ottoman Empire finally conquered Egypt. With the conquest of Yemen and the Sudanese port city of Sawakin and the control of Aden , asch-Schihr and the Abyssinian coast between 1538 and 1540 , the Ottomans succeeded in thwarting the Portuguese plans. At the same time, Bayezid II proved to be the patron of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, as a Portuguese naval blockade would have hindered the pilgrimage . The sultanate thus gained in importance for the entire Islamic world.

Due to its rivalry with the Habsburg Empire in the Mediterranean and Central Europe, the Ottoman Empire supported the trade of England and France in the Levant, so that the Venetian monopoly in the spice trade with Europe broke. Around 1625, when England and the Netherlands had consolidated their presence in the Indian Ocean and dominated Portugal in the Atlantic, the spice trade in the Red Sea came to a standstill. The tariffs from the Arab coffee trade and the increasing silk trade made up for the losses initially.

Alliances with the Sultanates of Gujarat and Aceh

With the establishment of the Ottoman province of Basra and an alliance with the sultanates of Aceh and Gujarat, the empire consolidated its position in the Indian trade . In 1566 the Sultan of Aceh recognized the Ottoman Sultan Selim II as the patron of the Muslims of his country and the Maldives as well as the Indian Muslims. Under Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha , the empire carried out a naval expedition from 1568–1570, in particular to secure the passage through the Strait of Malacca .

Control of the sea route in the Persian Gulf

In 1509 Portugal had conquered Hormuz , and with the Strait of Hormuz it controlled access to the trading ports of Bahrain , al-Hasa and Basra in the Persian Gulf . From 1545 efforts began in the Ottoman Empire to conquer these regions. The Ottoman governor of Baghdad, conquered in 1534, was given the task of setting up a fleet for this purpose. In 1546 Ottoman troops occupied Basra, where a strong naval base was established. In 1552 an attempt by the fleet under Admiral Piri Reis to conquer Hormuz failed. In 1556 a Portuguese attack on Basra failed, and in 1558 an Ottoman attack on Bahrain. Between 1552 and 1573 the Portuguese plundered the port city of al-Qatif several times . In return for enormous tribute payments, Portugal allowed Muslim traders on Hormuz to move freely on the Indian Ocean, with the exception of the Red Sea, which was controlled by the Ottoman Empire. Until the conquest by the Persian Shah Abbas I in 1622, Hormuz remained an important center of the Indian trade under Portuguese rule.

As a result of the Ottoman defeat in the naval battle of Lepanto and the enormous economic burden caused by the Ottoman-Safavid War (1578–1590) and the Long Turkish War of 1593–1606, world politics and trade changed again fundamentally. With the appearance of the British (1600) and Dutch East India Companies (1602), Portuguese supremacy in Indian trade was broken.

Caravan routes

A caravan road led from Basra to Aleppo and on to Bursa . Mainly spices, indigo and fine cotton fabrics from India were transported. In the second half of the 16th century there was a colony of Indian traders in Aleppo, which was reached by land via Basra, Baghdad, Ana and Hīt , as well as directly via al-Kusair , Kerbela , Kabisa and Kusur al-Ihwan. The importance of Aleppo at this time is also reflected in the fact that trade with Venice was increasingly carried out via Aleppo and no longer via Damascus.

Political unrest such as the Celali uprisings or the rebellions of provincial governors made the land routes unsafe until around 1640. Production and trading cities such as Bursa , Urfa , Ankara or Tosya were repeatedly occupied and looted. Wars like the Ottoman-Safavid Wars also repeatedly interrupted the caravan routes.

Trade with Europe

Trade routes

A west-east trade route important for the Mediterranean trade connected India via the Arab ports of Aden and Yemen and the Middle East with the republics of Genoa and Venice . Since around 1400 goods have also operated in a north-south direction via Damascus , Bursa , the Black Sea port of Akkerman and the Polish Lwow to Poland, the Baltic states and the Grand Duchy of Moscow . Another important north-south route ran via the Danube ports and Transylvania cities such as Brașov to Hungary and Slovakia.

The Republic of Venice was a center of Ottoman trade in the Mediterranean. In 1621 the Fontego dei Turchi was made available to Ottoman merchants. The presence of Ottoman traders in Poland, Lithuania, and the Grand Duchy of Moscow has also been proven from archive sources. The Republic of Ragusa (today: Dubrovnik ) competed with Venice in the 15th and 16th centuries. Much of the goods traffic between Florence and Bursa was handled via the city port of Dubrovnik . Florentine goods were transported to Dubrovnik by sea via the ports of Pesaro , Fano or Ancona . From there, the goods could be transported overland via Sarajevo - Novi Pazar - Skopje - Plovdiv - Edirne .

Black Sea and Eastern European trade

The area around the Black Sea and the Aegean have been closely linked economically since ancient times . The sparsely populated regions north of the Black Sea exported food to the densely populated areas south of the sea and the Aegean Sea in exchange for wine, olive oil, dried fruit, and luxury goods. After the collapse of Byzantine sovereignty after 1204, Venice took control of trade between Constantinople and the western Aegean, while the Republic of Genoa secured the Black Sea region and the eastern Aegean. To this end, the Latin republics first set up small trading establishments, which were strengthened with increasing economic influence and expanded until they finally dominated trade almost completely. After the conquest of Constantinople, Mehmed II had to rebuild the politically and economically ruined city as the capital. The strong population growth of Constantinople was only possible because the Sultan managed to conquer the Black Sea region with its ports in Moldova and Crimea, which is so economically important for the city . This was achieved with the help of the control of the Bosphorus passage through the Rumeli Hisarı fortress built in August 1452 . Shortly after the conquest of Istanbul, the Genoese trading colony of Pera also submitted . Under Ottoman rule, Pera ( Beyoğlu ) and the nearby Galata developed into the most important trading center between the Black Sea region and Europe, as well as an important center of intercultural exchange.

Tatar and Muscovite trade route