Muhtasib

A muhtasib ( Arabic محتسب, DMG muḥtasib ) is, according to Islamic law, a person who exercises Hisba, i.e. who fulfills the religious duty of exercising what is right and prohibiting what is reprehensible . In most of the Islamic states of the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Era , this task was organized in the form of a public office, also known as Ihtisāb ( iḥtisāb /احتساب) was designated. In Morocco , Pakistan and the Indonesian province of Aceh , this office still exists today in various forms.

The first muhtasibs were appointed in Iraq in the 8th century . By the 13th century, the office was also introduced in Egypt , Iran , Syria , Anatolia , al-Andalus and India . The muhtasibs were used either by the ruler, vizier or qādī and usually had a larger number of auxiliary officials. The tasks of the Muhtasib and the rules that apply to it have been described in Hisba tracts, treatises on constitutional law and administrative manuals. Accordingly, the Muhtasib had to monitor the observance of the religious rules of Islam, uncover violations and punish the guilty. Its supervisory function extended in particular to the public roads, markets, baths , mosques and cemeteries . In the markets, he was responsible for inspecting trade and detecting fraud, checking weights and measures and monitoring prices.

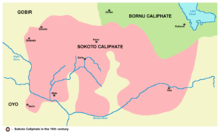

In the early modern period, the nature of the muhtasib office changed in various ways. It became common among the Mamluks , the Ottoman Empire , Iran and Morocco for the Muhtasib not only to control the prices of food, but also to set them. In addition, the office, which was originally remunerated, was increasingly awarded as a tax lease : when appointed, candidates for office were obliged to pay certain sums to the state, in return for which they were allowed to collect fees and protection money from traders and craftsmen. In addition, the Muhtasib in these states lost its role as guardian of observance of religious regulations. However, awareness of the religious dimension of the office was never lost. In the course of recent history there have been repeated attempts to revive the Muhtasib in his role as a moral guardian, for example among the Timurids , in the Mughal Empire under Aurangzeb , in the Sokoto Caliphate , in the Emirate of Bukhara , in the Indonesian province of Aceh and in the Pakistani province Northwest Frontier Province .

Overall, the Muhtasib was one of the most important institutions in the social fabric of medieval and early modern Islamic cities . Susanna Narotzky and Eduardo Manzano see the great importance that the muhtasib had in Islamic history as overseer of the markets as an indication that the economy in the Islamic world was dominated by the concept of moral economy . The Muhtasib office was taken over in individual Christian states in Spain and the Near East in the Middle Ages. The modern office of the ombudsman is also traced back to the Muhtasib in legal history.

Word origin and translation

The Arabic word muḥtasib , which is composed of the same root consonants as the word ḥisba , is an active participle of the Arabic verb iḥtasaba . In addition to other meanings such as “to count”, “to account” and “to consider”, this verb the religious meaning "to charge a pious act for oneself from God and to expect reward in the hereafter". According to general opinion, the term is derived directly from this meaning of the verb. For example, a 10th century Zaidite text says: “The Muhtasib is called Muhtasib because in his affairs he counts as a good deed that which God is well pleased with.” Maurice Gaudefroy-Demombynes explains that the Muhtasib term originally referred to a person who hopes for an otherworldly reward for their work in favor of the Islamic order, whereby this is also called ḥisba in Arabic . Michael Cook thinks that the Arabic term ḥisba initially referred to very different pious acts and only in the course of time became the term technicus for the area of what is right and the prohibition of what is wrong. The meaning of the word muḥtasib changed accordingly .

Since there is no exact equivalent for the Arabic term muḥtasib in the Western languages , translation is difficult. In English, the office of Muhtasib is often identified by terms such as market inspector ( "Market Overseer") or public moral officer (such as "general morality officer rendered"), but none of these translations captures the totality of perceived by Muhtasib tasks. That is why S. Orman and ASM Shahabuddin suggested leaving the word untranslated when translating into Western languages.

In German, very different terms are also used in the translation, for example “Marktmeister”, “Marktaufseher”, “Markt- und Sittenvogt” or “Sittenwächter”. In the German translation of the Arabic novel az-Zainī Barakāt by Gamāl al-Ghītānī , which has a muhtasib as the protagonist , the term is rendered as “holder of the office of oversight of public order”. Hartmut Fähndrich , who created this translation, justifies the choice of the term with the fact that, on the one hand, the tasks for which the Muhtasib was responsible are largely carried out in German-speaking countries today, and on the other hand the awkwardness of the title is intended to emphasize the extraordinary importance of this historical office.

General Hisba Duty and Muhtasib Office

The Muhtasib as a private person

According to Islamic law, everyone who performs the Hisba is basically a Muhtasib. According to al-Ghazālī , in order to be able to work as a Muhtasib, a person only has to meet three requirements:

- He must be sane (mukallaf) , so he must not be a madman (maǧnūn) or a child (ṣabī) .

- He must be a Muslim and have faith (īmān) , since no “help for religion” (nuṣra li-d-dīn) , as represented by Hisba, can be expected from an unbeliever .

- He must be able to act (qādir) . On the other hand, those who are unable to act can only perform Hisba in their hearts.

In contrast, al-Ghazālī does not regard integrity ((adāla) as a prerequisite for muhtasib. In his view, a sinner (fāsiq) also has the right to correct others. Otherwise, he believes, Hisba would become impossible because no one except the prophets possessed sinlessness and their sinlessness is controversial. According to al-Ghazālī, women and slaves can also work as muhtasib.

Al-Ghazālī, on the other hand, does not consider it necessary for the muhtasib to be authorized by the imam or ruler. Rather, in his opinion, every Muslim is a muhtasib who exercises the duty to rule on what is right and prohibit what is wrong, even if he has no authorization from the ruler. According to al-Ghazālī, however, the muhtasib should have three personal qualities as far as possible: knowledge (ʿilm) , piety (waraʿ) and a good character (ḥusn al-ḫuluq) .

The view that every Muslim who practices Hisba is a Muhtasib is also found in the Indian author as-Sunāmī (13th century). In his opinion, however, only someone who takes action against all violations of the same kind and does not limit himself to those that impair his own rights can be considered a muhtasib. If, for example, he demolishes an extension that blocks the passage on a street, he must demolish all the extensions that impede the traffic in this street, otherwise he is just a troublemaker (mutaʿannit) .

In al-Andalus , the Islamic part of the Iberian Peninsula, until the 11th century the term mutasib only referred to private persons who performed the Hisba spontaneously and unselfishly. For example, the scholar al-Chushanī (d. 971) reports of such a Muhtasib in Cordoba who denounced a man for drinking wine to the authorities. Such muhtasibs, who were not employed by the authorities, played an important role in the judicial practice of the city-state of Córdoba in the 11th century. They appeared there as the plaintiff and advocate of “good morals” before the market governor (ṣāḥib as-sūq) or Qādī. In the 1060s, for example, such a Muhtasib in Córdoba drew attention to the poor work of shoemakers and used violence in the process. In order to prevent him from doing this, the shoemakers complained to the market governor. However, their complaint was dismissed.

The Muhtasib as an official

Although the Hisba, as the domain of what is right and forbidding injustice, is a duty that fundamentally affects every Muslim, most Muslim authors reserve the term muḥtasib for those persons who ex officio perform this task. Al-Māwardī (d. 1058) was of decisive importance for this narrowing of the term . In the chapter on the Hisba in his state-theoretical treatise al-Aḥkām as-sulṭānīya , nine points are listed that distinguish the Muhtasib from those who practice the Hisba as a volunteer (mutaṭauwiʿ) :

- The Hisba is incumbent on the Muhtasib through his office as an individual duty, while it is incumbent on other people only as a collective duty (farḍ kifāya) .

- For the muhtasib, the performance of this duty is one of the rights of his control, while for others it is only one of the supererogatory acts that can also be neglected.

- He is appointed to his office so that people turn to him about things that must be disapproved of.

- In contrast to other people, it is up to him to respond to the input of the person who turns to him.

- The muhtasib must investigate apparent misconduct in order to be able to stop them and investigate apparent neglect of religious duties in order to be able to order their performance. No other person has this duty to investigate.

- In contrast to other persons, the Muhtasib can get helpers (aʿwān) who support him in the fulfillment of his duty.

- In contrast to other people, he can chastise the delinquent in the case of obvious offenses, but without being authorized to impose Hadd sentences .

- He can be paid for his Hisba activity from the state treasury, in contrast to the one who does Hisba voluntarily.

- He can practice idschtihād himself (i.e. finding norms through independent judgment) on things that concern custom , such as market rules , unlike someone who voluntarily practices Hisba.

In the following sections, the muhtasib will only be treated in this second meaning as an official appointed by the state.

Early history of the Muhtasib office

Hakīm ibn Umaiya, the first Muhtasib?

When the Muhtasib office was created is unclear. The earliest person who is specifically mentioned in Arab sources as Muhtasib was Hakim ibn Umayya, a man of the Banu Sulaym , who in the time of Mohammed as a sojourner (Halif) of the Banu Umayya lived in Mecca. Several Arabic sources report that the Quraysh used Hakīm as rulers over their careless young men (sufahāʾ) . He pushed her back and rebuked her. Two Arabic authors, Ibn al-Kalbī (d. 819) and al-Balādhurī (d. 892), use the term muḥtasib in connection with this educational task . Ibn al-Kalbī writes that Hakīm was installed in the Jāhilīya as Muhtasib over the Banū Umaiya and forbade the reprehensible. Al-Balādhurī reports that Hakīm was a muhtasib in the Jāhilīya who commanded the right and forbade the reprehensible. He had rebuked, imprisoned, imprisoned and banished the sinners (yuʾaddib al-fussāq wa-yaḥbisu-hum wa-yanfī-him) .

Research has drawn different conclusions from the two statements in Ibn al-Kalbī and al-Balādhurī. While Pedro Chalmeta, Meir Jacob Kister and Ahmad Ghabin assume that the Muhtasib office actually already existed in pre-Islamic Meccan society, Isān Ṣidqī al-ʿAmad, Michael Cook and RP Buckley regard the use of the name Muhtasib for Hakīm as an anachronism because they are convinced that this name only appeared in the Abbasid period.

The beginnings of the Muhtasib office in Iraq

An argument against the existence of the muhtasib office in pre-Islamic Meccan society is that such an office is not mentioned in the historical reports about the time of the first caliphs and the early Umayyads. The only other evidence of the existence of this office from the time before the Abbasids can be found in the biographical entry on the Qādī Iyās ibn Muʿāwiya (d. 740) in al-Balādhurī. Here it is narrated that marUmar Ibn Hubaira after his appointment as governor of Iraq by Yazid II. (R. 720-724) called on Iyās to take over the Qādī office in Basra . When Iyās refused, Ibn Hubaira had him flogged and forced him to take over the Hisba in the city of Wāsit. Elsewhere, al-Balādhurī reports of a man named Abān ibn al-Walīd who served Iyās as secretary and carried him an inkwell and papyrus scroll (qirṭās) "when Iyās oversaw the market in Wāsit and the Hisba" (wa-kāna Iyās yalī sūq Wāsiṭ wa-l-ḥisba) . The language in the source suggests that Market Authority and Hisba were viewed as two separate offices.

From the Abbasid period, the sources for the Muhtasib office flow more abundantly. So it is reported from ʿĀsim al-Ahwal (d. 759), who worked as Qādī in al-Madāʾin under the caliph al-Mansūr , that for a time he was given the Hisba for the weights and measures in Kufa . The earliest person after Hakīm ibn Umaiya, who is expressly mentioned in the sources as Muhtasib, was a certain Abū Zakarīya Yahyā ibn ʿAbdallāh. The Abbasid caliph al-Mansūr transferred the Hisba of Baghdad to him in 157 (= 773/774 AD) . He used his position, however, to alliance with the followers of the two Hasanids Muhammad an-Nafs az-Zakīya and Ibrāhīm ibn ʿAbdallāh , which is why the caliph had him executed. In the 10th century, the Muhtasibs of Baghdad were usually installed in their office by the viziers . Ibrāhīm ibn Muhammad Ibn Bathā, who was in Baghdad Muhtasib in the early 10th century, received 200 dinars a month for his services .

One of the most famous men who held the Hisba office during the early Abbasid period in Iraq was Ahmad ibn at-Taiyib as-Sarachsī (d. 899), a disciple of the philosopher al-Kindī . He held the office from 895 for the caliph al-Muʿtadid , but then fell out of favor with him, was imprisoned and died in prison. As-Sarachsī is also the first scholar known to have written stand-alone books on the Hisba. In addition, he also wrote texts about music, entertainment and singing. During the Buyid period, the Muhtasib office of Baghdad was held for a time by the Shiite poet Ibn al-Hajjaj (d. 1000), who was known for his revealing and obscene poetry. As-Sarachsī and Ibn al-Hajjāj are considered to be evidence that the occupation of the office in the Buyid period was not tied to high moral standards.

The Iraqi teachings about the Muhtasib office are recorded in the state-theoretical work al-Aḥkām as-sulṭānīya , which the Shafiite scholar al-Māwardī (d. 1058) possibly wrote on behalf of the Abbasid caliphs.

Introduction of the office in other areas

Egypt

Since the Tulunidenzeit (868-905) to officials of the Hisba can also prove in Egypt. The muhtasib is also mentioned in Arabic sources from the time of the Ichschididen (935–969). The Egyptian author Ibn Zūlāq (d. 996) reports that one complained to Abū l-Fadl Jafar ibn Abī l-Fadl, the vizier of Abū l-Misk Kāfūr (r. 946-968), about the administration of a Muhtasib and demanded its replacement.

The Muhtasib had a particularly high position among the Fatimids , who conquered Egypt in 969 and shortly thereafter entrusted a person with this office. A contemporary author, the Arab geographer al-Muqaddasī (d. After 990), describes that the Muhtasib in Fustāt was as powerful “as an emir” (ka-l-amīr) . In his office he sat alternately one day in the Friday mosque in Cairo and one day in the Friday mosque in Fustāt. He had a number of deputies in the two cities and in the remaining provinces who made their rounds at the grocers there. As al-Qalqashandī reports, when the muhtasib was installed, the letter of appointment was read publicly in the two Friday mosques in Fustāt and Cairo. On this occasion, some Muhtasibs were given an honorary robe and a turban and were led through the city in a solemn procession.

For the Fatimids, the Muhtasib was mainly responsible for the bread and grain supply. When he took up his post he had to guarantee that bread and grain would be available until the next harvest. It is known from chronicles that the Muhtasib also set the prices of staple foods in times of famine. In addition, the muhtasib was responsible for the calibration house (Dār al-ʿIyār) , in which the scales and measurements of the sellers had to be checked regularly. In addition, the Muhtasib also supervised the money changers (ṣaiyārifa) , who had semi-official status, and could dismiss them in the event of misconduct. As a punishment, the Muhtasib usually had the delinquents whipped or dishonorably led through the city.

Among the Fatimids, the Muhtasib was usually chosen from among the most respected notables . Occasionally, however, outsiders were entrusted with the Hisba, for example in 383 (993/4 AD) the Christian al-Wabira an-Nasrānī and in 391 (1000/1001 AD) the greengrocer Ibn Abī Najda. However, the latter was only withdrawn a short time later because of various misconduct. The Muhtasib received a monthly salary of 30 dinars for his services. Hisba, the judiciary and the supervision of coins were often in one hand with the Fatimids. Some Muhtasibs were also active as Wālī at the same time .

Hisba tracts were later written in Egypt. One of the most important of these tracts was written by Muhtasib Ibn Bassam. The earliest manuscripts of this work, entitled Nihāyat ar-rutba fī ṭalab al-ḥisba, date from the mid-15th century, but it may have been written well before that time. Ibn Bassām (14th century) explains in his treatise that the ruler is obliged to provide the Muhtasib with sufficient livelihood, to help him and not to counteract and not to intercede with him for anyone.

Iran

In the Iranian territories, muhtasibs were used for the first time during the Buyiden period (from 930). Thus, among the texts that are passed down from the Buyid vizier as-Sāhib Ibn ʿAbbād (d. 995), there is a certificate of appointment for the Muhtasib of the city of Raiy . The Muhtasib office is also described in great detail in the Buyid prince mirror Siyāsat al-mulūk , which was edited by J. Sadan and dated by him to the middle of the 10th century. From an anecdote cited by Nizām al-Mulk in his state-theoretical work Siyāsatnāma , it emerges that the Ghaznavid ruler Mahmud of Ghazni (r. 998-1030) also had a Muhtasib.

Nizām al-Mulk, who worked as Grand Vizier in the time of the Seljuk rulers Alp Arslan (r. 1063-1072) and Malik Shāh (r. 1072-1092), recommended in his Siyāsatnāma that the ruler should use a Muhtasib in every city. The ruler and his officials should give him a lot of power, because this is a basic rule of rule and corresponds to reason. Otherwise the poor would find themselves in need, the merchants only acted at will, the “ fala-ḫōr ” (faḍla-ḫōr) were given a dominant position, rip-offs would spread and compliance with Sharia would lose its luster. If, on the other hand, the right muhtasib has been used, all things take place in just balance (bar inṣāf) and the foundations of Islam (qawāʿid-i islām) are secured.

It is not known how far Nizam al-Mulk's recommendation was followed. However, a certificate of appointment proves that the Seljuk ruler Sandjar (ruled 1117–1157) later appointed a certain Auhad ad-Dīn to muhtasib of the Mazandaran province . The certificate of appointment shows that the Muhtasib was entitled to support from the Shihna, a kind of "security officer". An anonymous certificate of appointment for a muhtasib, which is received in an administrative manual by Raschīd ad-Dīn Watwāt (d. 1182), indicates that the Khorezm Shahs also set up muhtasibs in their territory. However, as early as the 13th century, the moral depravity of the Muhtasibs became a commonplace in Persian poetry. Saʿdī (d. 1292) castigated the bigotry of the Muhtasibs in his poems , who drank wine themselves but punished others for it.

It is possible that the muhtasib office was introduced in Iran even before the Buyids, because there is a Hisba manual which is traced back to the Zaidite imam an-Nāsir al-Hasan ibn ʿAlī al-Utrūsch (d. 917) who was written in ruled Iran's Caspian regions in the early 10th century. This Kitāb al-Iḥtisāb begins by stating that, according to the consensus of the Ahl al-bait, it is necessary to establish a muhtasib “in each of the great cities of Muslims” (fī kull miṣr min amṣār al-muslimīn) and contains detailed instructions for the muhtasib.

Syria and Anatolia

In Syria, the Muhtasib office can be traced for the first time in the early 11th century. The earliest known Muhtasib by name was the Maliki scholar Ibrāhīm ibn ʿAbdallāh (d. 1013), who came from al-Andalus and was appointed to his office in 1004. He was known for his strict administration and is said to have hit a donut seller so hard for insulting the Prophet's companions that he died a few days later of his injuries. Tughtigin (d. 1128), who acted as the Atabeg of Damascus from 1104 and founded the Burid dynasty, also used a muhtasib. During the Ayyubid period (1174–1260) other Syrian cities were also equipped with muhtasibs. For example, there is a letter of appointment for the Muhtasib of Aleppo , which Saladin installed there when he conquered this city in 1183. It was drawn up in Arabic rhyming prose by his secretary ʿImād ad-Dīn al-Isfahānī (d. 1201) and is handed down in his autobiographical historical work al-Barq aš-Šāmī ("The Syrian Lightning"); In 1978 it was edited by Charles Pellat .

The increasing importance of the Muhtasib office in Syria can also be seen from the fact that the Sunni scholar ʿAbd ar-Rahmān ibn Nasr al-Shaizarī wrote the first Syrian Hisba manual at this time. This work, entitled Nihāyat ar-rutba fī ṭalab al-ḥisba (“The highest degree in the study of Hisba”) has become the most popular Hisba manual. According to al-Shaizarī, the muhtasib should have servants and assistants, because this instills more fear and respect in the crowd, and he should also have spies to carry news of the people to him. On the basis of al-Shaizarīs work, the Egyptian scholar Ibn al-Uchūwa (d. 1329), himself a long-time Muhtasib, later compiled a new comprehensive Hisba treatise entitled Maʿālim al-qurba fī aḥkām al-ḥisba (“Sign of closeness to God on the rules of Hisba ”), which has also become very popular. Further works from Syria in which the Muhtasib office is described are the Hisba tract by Ibn Taimīya (d. 1328) and the book Muʿīd an-niʿam wa-mubīd an-niqam by the Syrian scholar Tādsch ad-Dīn al-Subkī (died 1370), which deals with the duties of the various Islamic classes of the population.

During the rule of the Rum-Seljuk Sultan Kılıç Arslan II (reigned 1156–1192) the Anatolian cities Konya and Malatya were also equipped with muhtasibs. According to a report given by al-Qazwīnī (d. 1283), the Anatolian city of Sivas also had a muhtasib in his time . However, the latter allowed wine barrels to be stored in a mosque in the city and was not reachable for a traveler who wanted to complain about it, because he had to sleep off his intoxication.

Al-Andalus and the Maghreb

In al-Andalus the Hisba was only introduced as a regular office in the 12th century. The scholar Ibn Baschkuwāl , who wrote in the middle of the 12th century, considered the term as a term for an office to be in need of explanation and therefore noted in a biographical entry: “The Hisba, which we call wilāyat as-sūq ('market supervision'). “In the early 13th century at the latest, however, the idea of the Muhtasib as the official responsible for the Hisba was firmly established in al-Andalus, because it is reported about the scholar ʿAlī ibn Muhammad Ibn al-Mu'adhdhin (d. 1224) that he was called "the Muhtasib" (al-Muḥtasib) because he long held the office of market supervision (ḫuṭṭat as-sūq) in his hometown of Murcia .

Ibn ʿAbdūn, who worked as Qādī and Muhtasib in Seville in the early 12th century , and Abū ʿAbdallāh as-Saqatī, who worked as Muhtasib of Malaga in the first half of the 13th century , wrote the first Andalusian treatises in which the Tasks of the Muhtasib are described. Ibn ʿAbdūn assumed that the Qādī should use the muhtasib, but declared that he should not do so without informing the ra'īs , the head of the city. The Qādī, so Ibn ʿAbdūn further, should fix the Muhtasib a salary from the state treasury, support and protect him and support his decisions and actions.

Probably the earliest evidence of the Muhtasib office in the western Maghreb is found in the collection of Sufi biographies of Ibn az-Zaiyāt at-Tādilī (d. 1230). Here in the biography of the Sufi Marwān al-Lamtūnī (d. 1174) from Fez it is reported that he was called to Marrakech by the Qādī al-Hajjādsch ibn Yūsuf to take over the office of Hisba there. In the time of the Merinids , the Muhtasib of Fez installed a standard in the Qaisarīya market district so that all traders and craftsmen could take measurements. For Tunisia, the office is only occupied in the time of the Hafsids (1229–1574). The evidence, however, is very rare. At least they show that the office in Tunis existed in the 13th century.

India

In India, the office of Muhtasib was introduced during the Sultanate of Delhi (1206-1526). During the reign of Muhammad ibn Tughluq (ruled 1325-1351) the Muhtasib was given a village that brought him an annual income of 5000 tanka. The Muhtasib ʿUmar ibn Muhammad as-Sunāmī from Sunam in today's Indian state of Punjab wrote his own Hisba manual in the 13th century with the title an-Niṣāb fī l-iḥtisāb , which became very popular in India. It was translated into English by M. Izzi Dien. According to as-Sunāmī, the muhtasib should be paid from the jizya and the land tax (ḫarāǧ) .

The muhtasib according to the classical teaching

As can be seen from the previous section, a large number of texts were written between the 10th and 14th centuries dealing with the Hisba and the provisions applicable to the Muhtasib office. These texts include stand-alone Hisba tracts, constitutional treatises, and certificates of appointment that were issued when muhtasibs were installed. The following sections summarize the most important statements that these texts contain with regard to the personal requirements for assuming the Muhtasib office, the tasks to be performed by the Muhtasib and the powers conferred on him.

Personal requirements for the office holder

The personal demands on those who take on the office of Muhtasib are higher than those of those who practice Hisba as a private person. According to Ibn al-Uchūwa, the Muhtasib appointed by the ruler must not only be Muslim, adult, rational and capable of acting, but also free and blameless. The Andalusian Hisba author Ibn ʿAbdūn has a particularly long list of personal requirements for the Muhtasib. In his view, the muhtasib must belong to the "exemplary people" (amṯāl an-nās) . He must be a man, chaste (ʿafīf) , kind (ḫaiyir) , pious (wariʿ) , learned (ʿālim) , wealthy (ġanī) , noble (nabīl) , experienced in business (ʿārif bi-l-umūr) , wise (muḥannak) and intelligent (faṭin) .

Knowledge of the legal norms

Some authors, such as the Syrian scholar asch-Shaizarī (12th century) and the Persian clerk of the Nakhshawanī (14th century), said that the Muhtasib must also be a faqīh who knows the rules of Sharia in order to know what to do command and what to forbid. This view can already be found in the Muhtasib certificate of appointment from the Buyide period. In it it is stated that the incumbent was chosen because he was one of the "great legal scholars" (aʿyān al-fuqahāʾ) .

Courage towards those in power

According to Nizām al-Mulk , on the other hand, it was more important that the Muhtasib had the courage to exercise his control function also over the ruler and the military. He therefore recommended that the office should be entrusted to one of the nobles (ḫawāṣṣ) , either a eunuch (ḫādim) or an old Turk who pays no attention to anyone, so that high and low are afraid of him. He regarded the behavior of a Muhtasib in the time of Mahmud of Ghazni as exemplary, who did not shrink from beating up one of the ruler's most important military leaders when he found him drunk on the street. Ash-Shaizarī reports in his handbook of a Syrian Muhtasib who, immediately after his installation by the ruler Tughtigin, admonished his client to remove the mattress and pillows on which he was sitting, because they were made of silk, and also to take off his ring because he was made of gold. Ibn al-Uchūwa comments on this anecdote by saying that such behavior is the great jihad , because the Prophet said: "The best jihad is a true word with an encroaching ruler". Only if the Muhtasib had to fear for his life or property would this duty be waived for him.

piety

For al-Shaizarī, one of the most important duties of the Muhtasib was that he himself acted according to his knowledge, because his words must not conflict with his deeds. According to his opinion, the Muhtasib should strive for the good pleasure of God with word and deed, be pure intent and free from hypocrisy and contentiousness, he should neither compete with people in his office nor pursue boasting with his own kind. He should also keep to the customs (sunan) of the Messenger of God. This means that he is the mustache supports that underarm hair auszupft that pubic hair shaved, cut fingernails and toenails, clean and does not contribute to long clothes and with musk surrounds and other fragrances.

Incorruptibility

One of the personal requirements of the muhtasib is that he is impartial and does not accept bribes. He should stay away from people's money and should not accept gifts from workers and craftsmen. Ash-Shaizari explains that the Muhtasib must also oblige his servants and assistants not to accept any money from craftsmen or traders. If he learns that one of them has accepted a bribe or gift, he must fire him immediately so that there is no doubt about his honesty. Obviously there have been repeated attempts to bribe the muhtasib's assistants. As early as 993/94 a proclamation was read out from the Fatimids that the helpers of Muhtasib were no longer allowed to accept anything from anyone.

Areas of responsibility

Almost all works that deal with the Muhtasib make it clear at the beginning that the Muhtasib has to ensure that the areas of right and the prohibition of wrong are followed. Many certificates of appointment also name this as the main task of the muhtasib. It is divided into numerous sub-tasks, the importance of which varies depending on the region and time. As a general clause , al-Shaizari formulates the rule that the Muhtasib must eliminate and prevent everything that the Sharia forbids, while conversely he should approve everything that the Sharia allows. The following sections provide an overview of the tasks of the muhtasib based on the theoretical treatises, Hisba tracts and early certificates of appointment.

Market and trade supervision

According to Nizām al-Mulk, it is the duty of the muhtasib to oversee trading operations so that there may be honesty. He has to ensure that the goods that are brought in from the various areas and sold in the markets are not fraudulent or fraudulent. According to the Buyid administration manual , the suppression of fraud in the various trades is the linchpin of the Hisba (ʿalai-hi madār al-ḥisba) . To carry out the controls, the muhtasib should be constantly present on the markets. From ʿAlī ibn ʿĪsā, who held the office of vizier twice during the caliphate of al-Muqtadir (r. 908-932), it is narrated that he exhorted a Muhtasib, who often sat in his house, to do so Going around markets because the office of Hisba would not tolerate doorkeepers and the sin would fall back upon them. The Zaidite Hisba book explains that the muhtasib must inspect all the markets every morning. According to Ibn ʿAbdūn, the Muhtasib must also assign fixed places to the craftsmen in the markets, in such a way that everyone stands with their own kind. In addition, the Muhtasib should also regularly inspect the individual shops in the residential areas outside the markets.

The Buyid administration manual recommends that the Muhtasib should appoint a trader as his shop steward (raǧul ṯiqa) for each of the markets . Since the muhtasib is unable to keep himself abreast of all actions of the market people, it is recommended that he choose a trustworthy expert (ʿarīf) from each guild (ṣanʿa) who is familiar with their craft and about their cheating in the Picture is. He should oversee their affairs and inform the Muhtasib of their trade. Similarly, the as-Saqatī, who works in al-Andalus, explains that the Muhtasib should select confidants ( umanāʾ , so-called amīn ) from all groups of craftsmen who will support him in his work. As-Saqatī warns, however, that the Muhtasib should not inform these shop stewards about the control actions he is planning, because otherwise there is a risk that information about it seeps out and the delinquents are given the opportunity to disappear or to clear evidence out of the way, so that the actions of the Muhtasib come to nothing.

Asch-Shaizarī and Ibn al-Bassām list the various trades in the individual chapters of their books and provide the Muhtasib with the technical information for each of them, which enables him to check the quality of the products and to uncover wrongdoing and poor workmanship. The professional groups that the muhtasib was supposed to check at regular intervals also included bakers , harissa cooks and syrup manufacturers. The muhtasib was to keep the names of the bakers and the locations of their shops in a register. The sausage makers, who were notorious for their fraud, were only allowed to practice their craft in the immediate vicinity of the Dikka des Muhtasib so that he could better monitor them.

Doctors, ophthalmologists and pharmacists were also under the control of the muhtasib. Doctors had to swear to him the Hippocratic oath and promise not to administer harmful medicine or poison to anyone and not to give any woman a prescription for a drug that would induce an abortion . The Muhtasib should also examine the doctors through the book The Medical Examination (Miḥnat aṭ-ṭabīb) by Hunain ibn Ishāq and the ophthalmologists through the Ten Treatises on the Eye (al-Maqālāt al-ʿašar fī l-ʿain) by Hunain.

Supervision of measurements, weights and the coinage

According to Nizam al-Mulk, one of the duties of the muhtasib is to monitor the weights and to ensure that the correct weights are used in the goods that are sold in the markets. Ibn Taimīya sees it as one of the main tasks of Muhtasib to prevent diminution (taṭfīf) in measurements and weights. He relates this to the Qur'anic statement of Sura 83 : 1–3: "Woe to the narrowers who, if they allow themselves to be measured, like to take full, but if they measure or weigh themselves, give less." His contemporary too, the Persian author Nachjawānī, quotes this verse when describing the Muhtasib. He explains that the Muhtasib should prevent traders who are guilty of miscalculation and quote this verse from the Koran.

Ibn al-Uchūwa explains the Muhtasib that with dimensions as Qintār and Ratl must, weight units and Dirhams know, because they were the basis of all transactions and he must ensure that they are used in Sharia contemporary way. According to al-Shaizari, the Muhtasib has to urge the traders to constantly clean their scales from oil and dirt, because a drop of oil can stick to them and then make itself felt in the weight. He also recommends that the muhtasib should check the scales from time to time, when their owners do not expect it, so that they cannot use tricks. When the Muhtasib calibrates weights, he puts his seal on them. If at another location sealer for scales and capacity measures or mint masters were needed, the Muhtasib to select them.

Supervising the coins and checking the money changers were other tasks of the Muhtasib. So he had to check the fineness of the gold and silver coins at the Mamluks with the touchstone . and withdraw suspicious coins from circulation. He had to forbid the money changers from smearing dinar coins with coolant to increase their weight or from accepting counterfeit coins rubbed with mercury. He should also secretly watch the money changers and make sure that they did not violate the Ribā prohibition, i.e. that they were charging interest. Those who did not comply, he was to rebuke and expel from the market.

Price control and setting

According to Nizām al-Mulk, it is also the duty of the Muhtasib to control prices (narḫhā) . In this way, limits should be placed on the trader's individual pursuit of profit. According to the Zaidite Hisba book, the muhtasib should also forbid traders from fighting each other, loudly praising their own goods or "barking like dogs".

The question of whether the Muhtasib can also set prices was controversial. Ash-Shaizari said that the Muhtasib is not allowed to impose a certain selling price on the sellers of goods. As a justification, he referred to a hadith according to which the Prophet Mohammed had been asked to fix prices in a time of high prices, but had refused on the grounds that God alone would fix the prices. However, al-Shaizari adds that the muhtasib must force a trader to sell if he sees that he has hoarded a certain food by buying it at a time when the price was still low and then waiting for it to that it increases with the food shortage. He must do this because the monopoly is forbidden . Tādsch ad-Dīn as-Subkī stated that according to authentic tradition, fixing prices is forbidden to the Muhtasib at any time. But there are also dissenting opinions. It was said, for example, that fixing prices at times of inflation (alāʾ) are permissible. And according to another opinion, this is permissible if it is not about imported products, but domestic agricultural products.

In al-Andalus the hadith about the prohibition of price fixing was also known, but the Hisba manual of as-Saqatī contains clear instructions for the price-fixing procedure by the Muhtasib for some professions, so that it can be assumed that this prohibition was ignored. This is confirmed by a report by the historiographer Ibn Saʿīd al-Maghribī (d. 1286). Accordingly, the butchers in al-Andalus did not dare to sell the meat at a price other than that which the Muhtasib had set them on the price tag, because the Muhtasib sometimes sent small children to them as undercover agents. They bought something from him, which was then checked by the Muhtasib for its weight. If the weight did not correspond to the purchase price, he concluded that they were dealing with other people and punished them. In order to set the price, the Muhtasib had to estimate the value of the goods. In the case of food, this was usually done by calculating the cost of the ingredients and then setting a certain profit for the respective craftsman.

Control of traffic routes and waters

At the market, the muhtasib had to prevent firewood, straw, water hoses, dung or sharp objects that could tear the clothes of passers-by from being transported through the streets. If one of the traders put a bank in their shop in a narrow passage, the muhtasib would have to remove it and prevent the trader from doing it again. In addition, the Muhtasib was responsible for ensuring free passage in the streets of the residential areas . If homeowners drained dirty water or rainwater from their roofs through gutters onto the street, the Muhtasib had to see to it that they replaced these gutters with pipes through which the water is led into a pit under the house. Rainwater and mud were not allowed to be left on the streets. Therefore, the Muhtasib had to hire someone to remove them. Unless the ruler had the streets cleaned, the Muhtasib had to urge the residents of the district to clean their district themselves.

According to the Buyid administration manual, the Muhtasib should also see to it that the "people of depravity" (ahl al-fasād) do not sit around on the streets. If he saw someone who he knew had a livelihood through wealth or work begging for alms , he should rebuke and rebuke him for it. The Muhtasib was supposed to forbid boys from fighting in the street or throwing stones one after the other.

In addition, the muhtasib was also responsible for controlling shipping traffic. His job, for example, was to prevent the owners of ships from overloading their ships or leaving them in rough seas. At night, ships were only allowed to enter the water with his permission. The Muhtasib had to create a pontoon on the water for boats to which they could be tied. In addition, the Muhtasib should set up an expert (ʿarīf) in each port to treat all seafarers with justice and to regulate the sequence of duties between them.

In addition, the Muhtasib should ensure that no one urinates in the water of the rivers or that it is contaminated by garbage, dirty sewage from the dyers or cloth walkers or other things. In Damascus , the muhtasib had the additional task of controlling the water in the various streams and canals and ensuring that this water was available to all people and was not made the subject of illegal water use contracts.

Moral police duties

Another task of the Muhtasib was to enforce gender segregation in the markets and streets. According to the Buyid administration manual, the muhtasib was supposed to encourage shopkeepers to put up partition walls in their shops so that women could sit down and do their shopping from the outside without entering the shop. If there were people in the market who were specially chosen to deal with women, then the muhtasib should examine their way of life and their trustworthiness. Ibn al-Uchūwa explains that the Muhtasib should visit the places where the women gather as often as possible, such as the yarn and linen market, the river banks and the entrances to the women's baths. If he came across a young man there who was talking to a woman about anything other than business transactions or who turned his attention to a woman, he should rebuke him and prevent him from standing there. The Muhtasib should also rebuke men who sit in the streets of women for no reason. According to the Buyid administration manual, the muhtasib was supposed to prevent men from addressing women in the streets. He should pour ink on women who dressed too freely, so that they could dress again in the manner of “the people of Islam”.

A document from the Seljuk period obliges the Muhtasib to hold back women from contact with men and from listening to sermons in teaching sessions. According to al-Shaizarī, the Muhtasib should attend the meetings of the preachers (maǧālis al-wuʿʿāẓ) and prevent men and women from mixing there by putting a curtain between them. Men who pretended to be women (muḫannaṯūn) should be expelled from the land by the Muhtasib.

Supervision of the public baths

In addition, the Muhtasib had to regularly inspect the public baths and check whether the bath attendants were adhering to the rules that apply to them. He should impose on the bath house owners not to let anyone enter the bath without an apron . If the Muhtasib saw someone who had uncovered his ʿAura during his rounds of inspection in the baths , he should reprimand him. The muhtasib should instruct the bath house owners to maintain the baths and to keep their water sufficiently warm, to sweep the facilities several times a day and to clean the soap residue with fresh water so that people do not slip on them.

Supervision of mosques and cemeteries

The muhtasib's control function also extended to mosques and Friday mosques . After a Seljuk certificate of Muhtasib had their muezzins and Takbeer monitor -Rufer to check the prayer times to keep all illegal things from them and the sale of wine in their area to stop. According to Ibn al-Uchūwa, the Muhtasib should urge the overseers of the Friday mosques and mosques to sweep and clean the buildings of dirt every day, to shake the dust from their mats, to wipe their walls and to fill their candlesticks with fuel every evening. He should also examine the muezzins for their knowledge of the times of prayer. He should prevent those who did not know it from holding the call to prayer until they have learned it. According to the Zaidite Hisba text, the muhtasib is also supposed to prevent the muezzins from spitting in front of the mosque gate.

Ibn Taimīya explains that the muhtasib has the supervision not only of the muezzins but also of the imams and that those of them who are negligent in the performance of their duties must be held accountable. The Muhtasib should command the Koran readers (ahl al-qurʾān) to recite the Koran only in the psalmodying form (murattilan) permitted by God , while forbidding them to recite it in melodic and intonated form, as songs and poems are performed because this was forbidden by Sharia law.

Ibn Bassam explains that the Muhtasib should also prevent the Qadis from holding their court sessions in the mosques. In this context, he refers to a Muhtasib from Baghdad in the days of the caliph al-Mustazhir bi-'llah (1094–1118), who had forbidden the chief Qādī to hold court sessions in the mosque on the grounds that those involved in the process were customary did not comply with the cleanliness regulations applicable to the building and disturbed the peace and quiet. According to Ibn Taimīya, the Muhtasib should also ensure that there is no whistling or clapping in the mosques, because this contradicts the Koran (cf. Sura 8 : 35).

The Muhtasib should also visit the cemeteries regularly and make sure that they are not used as pasture for the cattle. He was also supposed to prevent women from gathering in cemeteries or other places to mourn. If he heard a woman complain or shout loudly, he should reprimand and prevent her from doing so, because the lament for the dead (nauḥ) is prohibited. According to Ibn ʿAbdūn, the Muhtasib should visit the cemeteries twice a day in order to prevent men from sitting on the open areas of the graves to seduce women.

Enforcement of religious rules

The implementation of the alcohol ban was also one of the tasks of the Muhtasib. The Zaidite Hisba text states that the muhtasib should forbid wine merchants from selling wine and chastise those who do not obey the precedent. According to al-Shaizarī, when the muhtasib comes across someone who drinks alcohol, he should give 40 to 80 lashes on the bare skin. Tādsch ad-Dīn as-Subkī marks the checking of the food (an-naẓar fī l-qūt) and the care of the alcoholic drink (al-iḥtirāz fī l-mašrūb) as one of the most important duties of muhtasib. As long as the wine merchant can pretend that he is selling sorbet or oxymel, and as long as the cook can pretend that dog meat is mutton, the Muhtasib must fear the wrath of God, because he must not be the reason for things that God denies Muslims have forbidden to get into their stomachs.

Furthermore, the muhtasib had to intervene in public use of prohibited musical instruments such as oboe, tanbur , lute, cymbal and the like. In this case, he should break the instruments apart so far that the individual pieces of wood could no longer be used for making music, and punish the musicians. In addition, the Muhtasib was supposed to ban singers and forbid slave traders to sell their slaves. In addition, it should prevent carpenters or turners from making backgammon or chess sets.

According to al-Māwardī, if the residents of a town or part of the city agreed to suspend community prayer in mosques and the call to prayer during prayer times, it was the responsibility of the Muhtasib to order them to perform community prayer and call to prayer. The muhtasib should not take action against individuals who did not appear for prayer unless they made it their habit. Ibn Taimīya gives stricter rules here. In his opinion, the muhtasib should command the crowd to perform the five prayers in good time and punish anyone who does not pray.

Combating heresies

It is generally believed that the muhtasib also has the task of combating heretical tendencies. The Zaidite Hisba text says that the muhtasib must prevent people from telling stories without knowledge of Islamic norms . He should also keep the “ignorant storytellers” (al-quṣṣāṣ al-ǧuhhāl) away from the mosques and prevent people from rallying around them. Al-Mawardi wrote: "If a Koranexeget interpreted the book of God in a way that it the literal language of the revelation through an esoteric heresy replaced that darkens their meanings unnecessarily, or when a traditionist thereby excels that he reprehensible Hadith puts forward that are repulsive or spoil the interpretation of the Koran, it is incumbent on the Muhtasib to disapprove and prevent this. ”Al-Māwardī is probably referring to representatives of Shiite teachings in a baffled way.

According to Ibn Taimīya, the Muhtasib should correct in word and deed those people who commit acts that contradict the Koran, the Sunnah and the consensus of the ancestors (salaf) of the Ummah . In his opinion, these included:

- the denigration of companions of the prophets as well as imams, sheikhs and well-known rulers of the Muslims,

- the questioning of the hadiths accepted by scholars ,

- the tradition of fictional hadiths imputed to the prophet,

- Exaggeration in the way that people are assigned a divine rank,

- the authorization of violations of the Prophet's Sharia law,

- Astray (ilḥād) in the names and signs of God (cf. sura 7 : 180), the twisting of words by removing them from their proper place (cf. sura 4 : 46), the denial of God's providence , and

- the performance of magical tricks (ḫuzaʿbalāt siḥrīya) and juggling based on physical laws (šaʿbaḏa ṭabīʿīya) , which resembles the miracles of prophets or friends of God .

As soon as someone was suspected of committing such unlawful innovations , the muhtasib should not only correct him, but also prevent people from seeing him.

Holding down the Ahl adh-Dhimma

According to popular belief, the Muhtasib was also responsible for suppressing the Ahl adh-Dhimma . So he should command them not to show any of their " idolatry " in public. According to a Seljuk document, the Muhtasib had the task of marking the Ahl adh-Dhimma with the prescribed yellow cloth (ġiyār) . According to al-Shaizari, the Muhtasib was also responsible for collecting the jizya . He explains that the Muhtasib should proceed in such a way that he first stands in front of the man in question, hits him with his hand on one side of the neck and then exclaims: "Do the jizya, o unbeliever !" (Addi l-ǧizya, yā kāfir) .

The Muhtasib's Authority and Its Limitations

Investigation and jurisdiction

According to the Maliki legal scholar Ibn Sahl (d. 1093), the office of Muhtasib goes beyond that of the Qādī in that the Muhtasib can independently investigate prohibited actions, even if they are not reported to him. The Qādī, on the other hand, only judges what is submitted to him.

Conversely, the Muhtasib's jurisdiction is very limited. According to al-Māwardī, he can only deal with indubitable cases in which a transgression has definitely taken place. Unlike the Qādī, he cannot rely on evidence or take an oath. If there is a conflict in the market over the question of a miscalculation, the muhtasib may only deal with the case as long as there is no mutual denial. But as soon as one of the parties to the dispute denies something, it is no longer the Muhtasib but the Qādī who is responsible for the case. Although the Muhtasib does not have jurisdiction, it has a control function over the Qādī. Thus, he has the right to stop the Qādī from fulfilling his duties if he refuses, without a reason to prevent it, to deal with the disputes of persons who turn to him, so that the judiciary comes to a standstill and the Litigation opponents suffer damage. Al-Māwardī emphasizes that the high rank of the Qādī should not prevent the Muhtasib from censuring his wrongdoing.

Unlike Eastern authors, who denied the Muhtasib any jurisdiction, Western authors assumed that it had such competence in a limited way. For example, the Andalusian scholar Ibn ʿAbdūn believed that in cases in which the Qādī was prevented, the Muhtasib could decide such things as were appropriate to him and his position. Ibn ʿAbdūn also stressed very strongly the need for cooperation between Muhtasib and Qādī and stated that the Muhtasib office was "the brother" of the Qādī office. He regards the Muhtasib as the speaker (lisān) , vizier , doorkeeper and deputy of the Qādī. Ibn Farhūn (d. 1397) stated that although the muhtasib was not authorized to rule on legal cases involving marriage or commercial transactions, he was also right in matters typical of Hisba such as the porches of houses that jut out onto the street could speak.

No spying

The Muhtasib's investigative mandate , however, was restricted by the prohibition of spying (taǧassus) . This states that the Muhtasib was not allowed to spy out offenses that did not take place in public. The Muhtasib was also not allowed to publicize such offenses. A certificate of appointment from the Khorezm Shah declares that the Muhtasib may not climb walls, raise veils, break open gates, or drag publicly what God has commanded to hide.

As a basis for the ban on spying, reference is made to a report according to which the second caliph ʿUmar ibn al-Chattāb (r. 634–644) once entered a man's house over the roof, saw him doing something forbidden there and rebuked him for it. The man replied that although he himself had violated a Koranic rule, ʿUmar had violated three of them, namely firstly “Do not spy!” (Sura 49:12), secondly, “Enter the houses through the doors!” ( Sura 2 : 189) and “Do not go into houses that are not your houses until you have asked for permission and greeted their inhabitants” (Sura 24:27). ʿUmar then gave up on him. The Indo-Persian historian Badā'unī (d. Approx. 1615) reports an incident in which private muhtasibs broke over the wall into the house of a scholar from Lahore who was known for his debauchery while he was drinking wine in the company of a singer. They smashed the wine jugs and musical instruments and wanted to punish him. However, like the man whose house ʿUmar had broken into, he referred them to the three verses of the Koran, thus making it clear to them that they had committed greater offenses than he did, whereupon they withdrew ashamed.

Anyone who commits a sin in their own home must not be spied on by the Muhtasib. Even if he hears the sound of forbidden musical instruments from inside a house, the muhtasib is not allowed to enter the house forcibly, but is only allowed to reprimand the wrongdoers from outside. According to Ibn al-Uchūwa, an exception should only apply if the offense includes the violation of a sacred good (intihāk ḥurma) that can no longer be restored. For example, if the muhtasib is told by a trustworthy person that a man has withdrawn into a house with another man in order to kill him, or has withdrawn there with a woman in order to have sexual intercourse with her outside of marriage, he may to avoid violating sacred goods and committing prohibited acts, investigate and spy on those affected.

The question of ijtihad

The question of how far the Muhtasib can use its own ijtihād when assessing dubious cases was controversial . According to al-Māwardī, he was only allowed to exercise his own ijtihād with regard to the questions that were judged according to the Urf . This urf-idschtihād concerns above all the question of what is harmful and what is not. In the case of questions that are judged according to the Sharia, however, the ijtihād should be denied. In addition, al-Māwardī reports that there is scholarly knowledge on the question of whether the Muhtasib may convert people to his own judgment on the reprehensible things on which legal scholars have different views, which he has come to on ijschtihād. He presents two different opinions within the Shafiite school of law . In the opinion of Abū Saʿīd al-Istachrī, who exercised the office of Hisba in Baghdad at the beginning of the tenth century , the Muhtasib was allowed to act in this way, but accordingly had to have the ability to do ijtihād with regard to religious norms (aḥkām ad-dīn) . According to the other opinion, the Muhtasib was not authorized to do so, but accordingly did not have to have any ijtihād qualification, but only knew the prohibitions on which there was agreement.

According to Ibn al-Uchūwa, a muhtasib who does not have sufficient knowledge and ijtihād competence may not judge religious teachings himself, but must rely on the consensus of the scholars when judging them. In this context, he warns of the great danger that an ignorant Muhtasib could interfere in things of which he does not understand anything. The damage it then causes is greater than the benefit.

Punitive violence

The main punishment tools of the Muhtasib were the whip, dirra and turtur. The Dirra was a cow or camel skin filled with date kernels. It is said to have been an invention of ʿUmar ibn al-Chattāb . The Turtūr is a felt hat that was decorated with colorful patches of fabric, onyx , shells, bells, foxtails and cat tails. It was put on the head of the delinquent when he was led through the city on the punishment donkey as part of a penalty of honor .

For some offenses that the Muhtasib had to pursue, specific corporal punishments are given. Ash-Shaizarī says that if the Muhtasib comes across someone who drinks alcohol, he should give him 40 lashes on the bare skin. He should raise the hand holding the whip so that the white skin of his armpit was visible, and then distribute the lashes on his shoulders, buttocks and thighs. According to Ibn Taimīya, the Muhtasib had above all to punish those who did not pray with beating.

The question of whether the Muhtasib can independently impose prison sentences was disputed. The Buyid Muhtasib of Raiy was allowed in the certificate of appointment to imprison offenders. According to al-Māwardī, however, the Muhtasib was not allowed to imprison delinquents because this required the resolution of a Qādī. Ibn Taimīya said that the Muhtasib could punish those who did not perform the five prayers by imprisonment.

The Muhtasib, however, did not have the authority to amputate or kill the delinquent. According to al-Shaizarīs, however, the Muhtasib was responsible for executing the hadd punishment in the case of Zinā offenses if the offense was confirmed by the Imam. In the case of men and women who had committed zinā in the ihsān state, the muhtasib was supposed to gather a crowd outside the city to publicly perform the stoning of the delinquent with them . If the delinquent had committed fornication with a boy, the Muhtasib was supposed to throw him down from the highest point of the place.

Punishments that the Muhtasib was not authorized to carry out could be threatened with delinquents in order to intimidate them. Ibn al-Uchūwa justifies this with the fact that Solomon had done the same in his judgment on the two prostitutes. The deterrent function of the muhtasib is also emphasized by other authors. Ash-Shaizarī explains that the Muhtasib should hang his three punitive instruments (whip, dirra and turtur) on his dikka in order to intimidate potential delinquents. He was supposed to frighten professional groups like pharmacists, whose frauds could hardly be controlled, particularly often by threats of punishment. Al-Māwardī declares that when the muhtasib exercises his office with sharpness (salāṭa) and rudeness (ġilẓa) , he is not guilty of transgression or violation of the law, because the Hisba is an office which serves to arouse fear (Ruhba) .

Special features of the Zaidites

The Muhtasib had some special tasks with the Zaidites. He was responsible for ensuring that the formula Ḥaiya ʿalā ḫayri l-ʿamal , which is the hallmark of the Ahl al-bait , was recited during the call to prayer and the Iqāma , and he was supposed to forbid believers from putting on their shoes before prayer . If a person escaped from the Zaidite Imam , it was up to the Muhtasib to tear down his house.

A peculiarity of the Zaidi constitutional law is that it also grants the Muhtasib political and military powers. In the absence of a legitimate imam, the muhtasib can take on the role of corruption . He is then responsible for defending the country and the borders against attackers, preserving the foundations , inspecting water points, mosques and paths and averting attacks among the population. If a legitimate imam appears, he must resign immediately.

The post after the end of the Abbasid caliphate of Baghdad ...

After the end of the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad (1258), the office of Muhtasib was continued in the various Islamic states, although various changes occurred, which are described in the following sections.

... with the Mamluks in Egypt and Syria

Under the Mamluks (1250–1517) there were three muhtasibs in Egypt, one in Cairo, who was also responsible for Lower Egypt with the exception of Alexandria , one in Alexandria, who was only responsible for this city, and finally one in al-Fustāt , whose area of jurisdiction extended over all of Upper Egypt. The two Muhtasibs from Cairo and al-Fustāt were part of the ruler's court (al-Qaḍra as-sulṭānīya) , like the chief Qādī, the military Qādī, the four supreme muftis and the head of the financial authorities . The Muhtasib of Cairo held the highest rank of all the Muhtasibs. He had his seat in the “House of Justice” (dār al-ʿadl) below the head of the tax office or, if he was more educated, above him. Muhtasibs were also found in the Syrian provinces. They were appointed by the provincial governors.

Changes in the appointment of offices

For the period between 1265 and 1517, a total of 184 muhtasibs can be found in Cairo, 30 of which held the office several times. For al-Fustāt, where the office only existed until 1440, 62 muhtasibs can be proven, of which 13 held the office several times. At the beginning of the 15th century five muhtasibs held office simultaneously in Cairo and al-Fustāt.

The Egyptian chancellery al-Qalqaschandī (d. 1418), who in his administrative manual luubḥ al-aʿšā describes the organization of offices in the Mamluk Empire, counts the Muhtasibs of Cairo and al-Fustāt as religious officials (arībāb al-waẓā'if ad- d-d-d ) to. However, the office in Cairo experienced a process of change over time, which led to the fact that more and more members of the military class were appointed muhtasib. With Jonathan Berkey, who evaluated the biographical and historiographical literature of the time, this process can be divided into six successive phases:

- In the period from 1260 to the end of the 14th century the office was almost exclusively given to members of the ʿUlamā ' . Many of them also functioned as qādī or taught fiqh at one of Cairo's numerous madrasas at some point . As can be seen from the Hisba book by Ibn al-Uchūwa (d. 1329), it was still considered the duty of the Sultan in his time to provide the Muhtasib with sufficient livelihood. From the 1380s, however, it became customary for the sultan to oblige the Muhtasibs to pay him a certain sum afterwards. The Muhtasibs could only make this promise because they themselves levied taxes on the dealers. This marks the transition to the tax lease system.

- From 1396 to 1413, the muhtasib office was particularly unstable: muhtasibs were often appointed and dismissed, sometimes reinstated and dismissed, within a very short period of time. The average term of office was less than three months. One person, Muhammad ibn ʿUmar al-Jābī, was appointed Muhtasib a total of 18 times during this period. The office became the pawn of various rival emirs who tried to fill it with their favorites. This is particularly evident in the so-called Muhtasib Affair (1399-1401), in which the two scholars al-Maqrīzī (1364-1442) and Badr ad-Dīn al-ʿAinī (1361-1451), who were involved in different systems of patronage , four times were exchanged for each other. For the first time, people who did not belong to the scholar class were appointed muhtasib during this time.

- The period between 1413 and 1422, which coincides with the rule of al-Mu'aiyad Shaykh , represents a transition period. The office is still often occupied by religious scholars, for example with the particularly strict Sadr ad-Dīn Ibn al-ʿAdschamī, but for the first time Mamluk emirs are also used. The average term of office of the Muhtasibs is increasing again. During a famine in 1416, the sultan took over the muhtasib office himself for a short time.

- During the reign of al-Ashraf Barsbāy , which lasted from 1422 to 1438, stability returned. Altogether there are only four changes of office: Badr ad-Dīn al-ʿAinī is reappointed Muhtasib twice, the other officials are an emir and a bureaucrat.

- In the period between 1438 and 1505 the office was occupied almost exclusively by members of the military class: high-ranking emirs or Mamluks who are on their way to this position. As a result, the office loses its religious character. The average term of office is 16 months.

- Between 1505 and the capture of Cairo by the Ottoman armies in 1517, the office was almost continuously in the hands of Zain ad-Dīn Barakāt ibn Mūsā, a man of Bedouin origin. He was able to amass enormous power as the sultan's companion and acted as his deputy in his absence.

Unlike in Cairo, in al-Fustāt the Muhtasibs were consistently selected from the class of religious scholars.

Changes in the field of activity

Contemporary chronicles show that some Muhtasibs of the Mamluk period took their religious control duties very seriously. Al-Maqrīzī mentions that in Rabīʿ al-auwal 822 (= March / April 1419) the Muhtasib Ibn al-ʿAdschamī visited the "places of perdition" (amākin al-fasād) and even spilled and smashed thousands of wine jugs . He also banned women from lamenting for the dead , banned hashish in public, and prevented prostitutes from looking for suitors in markets and dubious places. Ibn al-ʿAdschamī obliged Jews and Christians to narrow their sleeves , to reduce their turbans to a length of seven cubits , and to enter the baths only with bells attached to their necks. Their wives had to wear colored throws, the Jewish women yellow and the Christian women blue. But since a group of people took their side, only some of these measures were actually implemented, while others were not. A few months later, when news of poor treatment of Muslims by the ruler of Ethiopia reached Egypt, the Muhtasib was once again charged with taking action against Christians. For example, on behalf of the sultan, he insulted the Coptic patriarch on the grounds that the Christians had neglected the dress code imposed on them, and led the sultan's former Christian secretary naked through the streets of Cairo.

As before with the Fatimids, however, the main responsibility of the Muhtasib was seen to be food supply. This is also reflected on the level of the theoretical texts. Ibn Bassam explains that the muhtasib should have an agent on the seashore where the grain arrives, so that he can inform him of what he receives every day. The Muhtasib then had the task of distributing the grain according to the number of inhabitants in the country. Tādsch ad-Dīn as-Subkī defined it as the duty of the muhtasib to monitor food and to ensure that all essential items are available to Muslims. Muhtasibs who did not succeed in preventing price rises faced popular anger or were dismissed and sometimes even flogged.

In addition, the Muhtasib increasingly assumed the role of a tax collector responsible for the markets. In 1378 the Muhtasib of Cairo was given the task of collecting Zakāt from traders and money changers . As early as the middle of the 14th century it had also become customary for the muhtasib to collect a monthly fee from traders and craftsmen, which was called mušāhara . During the last hundred years of Mamluk rule, as the state's tax base decreased, this fiscal task of the Muhtasib became more and more important. The state was increasingly dependent on taxes collected from the Muhtasib. Individual Mamluk rulers made attempts in the 15th century to abolish the Hisba taxes, but they were unable to enforce them. The change in the function of the office also explains why more and more members of the military elite were entrusted with him.

The Hisba must have been a lucrative business because people were willing to pay amounts of up to 15,000 dinars to be appointed to this office . Conversely, the sums transferred from the Muhtasib to the state were also very high. Ibn Iyās reports in 1516 that they amounted to 76,000 dinars annually.

... among Ilkhan and Timurids

After their conversion to Islam, the Ilkhan also used muhtasibs in Iran. The Persian office secretary Muhammad ibn Hindushāh Nachdschawānī, who wrote an administrative manual for the Ilkhan around 1340, mentions a scholar named Diyā 'ad-Dīn Muhammad, who was appointed muhtasib of the capital Tabriz because of his great piety , in order to do so “as it is It is described in the law books to command what is right and forbid what is wrong and to make Muslim groups follow the traditions of Sharia law. ”Muhtasibs apparently existed in every province. When Ghāzān Chān decided to unify the weights and measures in his realm, he ordered that this should be done in each province in the presence of the Muhtasib.

The Muhtasib received no state salary from the Ilkhan people, but instead collected its own fees. Nachjawānī exhorted the bazaar traders to pay the weekly and monthly fees to the muhtasib and to hold back nothing. Nachdschawānī believed that price fixing by the Muhtasib was permissible, but warned that the Muhtasib had to strive for truthfulness (ḥaqq) and sincerity (ṣidq) because of the aforementioned Prophet's hadith and to set a price with which both the noble and the common people would agree . If traders or craftsmen set their own price instead, this should not be valid and the people concerned should be punished. Muhtasibs who used their authority to narrow the lives of the population should, according to Nachdjawānī, be removed.

The Timurids in Central Asia also used muhtasibs. Hans Robert Roemer has translated and evaluated three Muhtasib certificates of appointment from the Timurid period. They come from the Inschā 'work of the Persian scholar ʿAbdallāh Marwarīd (d. 1516), who himself held the Muhtasib office in the Timurid capital of Herat for a while. In these certificates of appointment, among other things, the pouring of wine and other intoxicating drinks as well as the breaking of the relevant vessels, the smashing of musical instruments such as guitars and flutes and the suppression of the pigeon players are named as tasks of the Muhtasib. It is reported that Shāh Ruch , who ruled Khorasan and Transoxania from 1409 to 1447 , gave the Muhtasibs great powers. The rule that the Muhtasib was not allowed to enter private houses was overridden under his rule. The Muhtasibs of Herat are also said to have entered the houses of high-ranking personalities and poured out the wine if they found any. Shāh Ruch's son Ulugh Beg , who ruled Transoxania from Samarkand from 1409 , also used a muhtasib there, but had several confrontations with him because both he and his Shaikh al-Islam often held celebrations at which wine was drunk and Women were present.

... in the Ottoman Empire

In the Ottoman core areas

The earliest mention of a muhtasib in the area of the Ottoman Empire can be found in a document from Bursa from 1385. Later many other Ottoman cities were also equipped with muhtasibs. The field of activity of the early Ottoman Muhtasib or Ihtisāb Ağası , as he was also called, is documented by several documents from Mehmed II and Bayezid II . A certificate of appointment from 1479 for the Muhtasib of Edirne assigns him religious and economic tasks: He is supposed to rebuke those who neglect prayer or drink intoxicating drinks, together with the market people set the maximum price (narḫ) for food and measures and weights to verify. Once a month he should check all the craftsmen. Those he encounters with incorrect weights or measures should be fined according to the gravity of the offense.

The supervisory and inspection duties of the Muhtasibs of Istanbul , Bursa and Edirne as well as the penalties and taxes to be imposed by them were codified in three very detailed Ihtisāb regulations in 1502. The regulations for Istanbul, which were translated by N. Beldiceanu and divided into 51 paragraphs, have some additional provisions compared to the classic Hisba rules. It was stipulated that the Muhtasib should check the grain market once a week (Section 15), that it should punish the substance dealers who do not comply with the regular parameters of the materials (Section 25) and that boat loads may only be sold with the consent of the Muhtasib ( Section 37). When setting prices, the Muhtasib should grant traders a profit margin of 10 to 15 percent; Moneylenders were allowed to take up to 12 percent interest. The Muhtasib should punish people who exceeded these maximum rates (§§ 5, 17, 40, 49). It was also determined that the Muhtasib should have those who did not pray with the help of the neighborhood imams monitored. If they did not change their behavior, he should punish them (§ 47). Depending on the case, punishments included lashing with a stick, fines, neck irons or dishonorable public showing around.

The Muhtasibs in the Ottoman core areas usually did not come from the class of scholars , but were military officials (çavuşlar) . In the 17th century, the Muhtasib of Istanbul was based in Çardak, a pavilion near the Yemiş landing stage on the Golden Horn , where the fresh fruit was delivered. Galata and Üsküdar had their own muhtasibs. The former were subordinate to deputies in Beşiktaş and Tophane .

As far as their status is concerned, two different types of muhtasib can still be distinguished in the 15th century: those who were provided for by a Tımar fief and those who were tax tenants . The tax lease system (iltizām) later became the norm. This stipulated that the office was reassigned annually, with the holder receiving a consultation and then having to pay a certain amount, which was called Bedel-i muqātaʿa . Once the Muhtasib was in office, he could raise his own taxes, including the daily shop levy (yewmiyye-i dekākīn) that all food vendors had to pay, the market duty (bâc-i pâzâr) that was levied on all goods coming from outside, the stamp fee (damga resmi) and various weighing and measuring fees. For the shop taxes, Istanbul was divided into 15 qol tax areas. The muhtasib was supported by the qol oğlānları in collecting these taxes . At the end of the 17th century, about three quarters of the shop taxes went to the state treasury, the rest was used to provide financial support for the forty active and retired Ihtisāb employees, to pay the rent of the Çardak and to cover running costs.

As early as the 15th century it happened that the Muhtasibs, in order to raise the money for the tax lease, made agreements with artisans in such a way that they allowed them to take higher prices for an additional fee. The High Porte tried again and again to prevent such practices. A decree of Mehmed IV from 1680 for Istanbul says: "If the Muhtasib makes arrangements with the people of the Sūq or does not supervise those who give less than the set price, he shall be punished."

Until the early 19th century, the Muhtasib office in the Ottoman core areas continued largely unchanged. In 1826 it was given additional powers by a new statute, the İhtisāb ağalığı nizāmnāmesi , but was abolished in 1854 in the course of the Ottoman administrative reforms .

In the Arab provinces

Muhtasibs were also found in several Arab provincial cities during the Ottoman period. In Jerusalem , the muhtasib was one of the city's highest officials in the 16th and 17th centuries. He set the prices of food in consultation with the political authorities and was also responsible for supplying the town with flour. The Muhtasibs were very often recruited from the butcher's guild.

A particularly large amount of information is available about the Muhtasib in Cairo, where from the end of the 16th to the end of the 18th century the office was usually assigned to a senior officer of the Chāwuschīya. The muhtasib was assisted by a number of assistants (aʿwān) who formed his entourage at public appearances. These assistants, who were paid by the Muhtasib, included a treasurer (ḫaznadār) , a scribe (mubāšir) , a weigher (wazzān) and various assistants who carried out the sentences imposed by the Muhtasib. The Muhtasib's area of responsibility, however, was limited to the supervision of the grocers, whose prices, weights and dimensions he controlled. He levied fees on fruit and vegetables brought into town, which he collected at the market. Impressive reports have been handed down in European travel literature of the rounds of control that the Muhtasib made through Cairo. On horseback and dressed in a black robe, he rode through the city with his entourage and a janissary escort, with the weigher running ahead of him with a large scale. The Muhtasib stopped at various shops and had their owners show them weights and measures so that they could be checked. If the measurements or weights were incorrect, the persons concerned were punished directly. The Cairo Muhtasib also had an important communication function in that it publicized communications from the government through criminals. In addition, he presided over the New Moon Sighting ceremony (ru'yat al-hilāl) , at which the beginning of Ramadan was announced.

Over time, however, the Muhtasib office in Cairo steadily lost its authority. This was partly due to the fact that cases of corruption and extortion by Muhtasibs had occurred repeatedly since the 17th century . Another reason was that the number of immunity areas beyond the control of muhtasib increased. For example, the Jews were able to exempt themselves from visiting the Muhtasib by paying a sum of money. In addition, the Janissary Agha acquired more and more competencies of the Muhtasib in the course of time.

After Muhammad Ali Pasha had ruled Egypt in 1805 , he tried to stop the decline of the Muhtasib office. In 1817 he installed a new Muhtasib in Cairo, which he endowed with very extensive powers to discipline the traders. This Muhtasib, whose name was Mustafā Agha Kurd, followed the classic Hisba rules and in 1818 ordered the residents of Cairo to clean the markets and streets and to remove the earth that had settled on them.