Taliban

|

Taliban |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Lineup | September 1994 |

| strength | over 60,000 (in 2014) |

| location |

Quetta , Pakistan Peshawar |

| equipment | Equipment captured from NATO forces stationed in Afghanistan during the 2001-2021 war and inventory from Soviet intervention in Afghanistan |

| Butcher |

Afghan Civil War (1989–2001) War in Afghanistan since 2001 |

| commander | |

| Current commander |

Haibatullah Achundsada (since 2016) |

| Important commanders |

Mohammed Omar † (1994-2013) |

The Taliban , also Taleban ( Pashtun د افغانستان د طالبان اسلامی تحریکِ DMG Da Afghanistan since Taliban Islāmī tahrik , German , The Islamic Taliban movement of Afghanistan ' ), a company incorporated in September 1994 deobandisch - Islamist terrorist group , which from September 1996 for the first big up in October 2001 parts of Afghanistan back keeps control in the country dominated and since August 2021 . The name ( Pashtun طالبان DMG ṭālibān ) is the Persian plural form of the Arabic word talib (طالب, DMG ṭālib 'student, seeker'). The Taliban's Islamic Emirate Afghanistan was recognized by Pakistan , Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates .

The Taliban consisted of previous mujahideen when it was founded . The Taliban movement has its recruiting origins in religious schools for Afghan refugees in Pakistan. The ideology of the movement is based on an extreme form of Deobandism and is also strongly influenced by Hanafi teaching and the Pashtun legal and honor code , the Pashtunwali . The leader of the Taliban was Mullah Mohammed Omar until 2013 . Omar's successor Akhtar Mansur was killed in a drone attack in 2016. Mansur's successor is Hibatullah Achundzada .

The Taliban first appeared in the southern city of Kandahar in 1994 . They took power in several southern and western provinces and took the capital, Kabul , in September 1996 . They then established the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan and conquered other areas in northern Afghanistan. Their rule was, among other things, increasingly characterized by radical intolerance towards minorities. In October 2001, their government was overthrown by troops of the Afghan United Front in cooperation with American and British special forces in a US-led intervention . Their leaders were able to sustain themselves by withdrawing to Pakistan.

From 2003 onwards, the Taliban launched a terrorist-military campaign from Pakistan against the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan and the international troops of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan. The Taliban apparently carried out targeted attacks against the Afghan civilian population more than twice as often as against the Afghan or international troops. A United Nations report shows that the Taliban were responsible for over 75% of the civilian deaths in Afghanistan in 2009 and 2010. Human rights organizations have led the International Criminal Court in The Hague to conduct a preliminary investigation into the Taliban for systematic war crimes.

story

Collapse of the central government and the battle for Kabul (1992–1994)

After the collapse of the Soviet-backed regime of President Mohammed Najibullah, the seven most important Sunni mujahideen parties reached negotiations at the United Nations in 1992 on a peace treaty, the Peshawar Agreement, which established the Islamic State of Afghanistan and established a transitional government. However, there were already numerous fights between various competing mujahideen in changing alliances among the new warlords on site in Kabul. Two important warlords trained by the Pakistani secret service ISI were Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Ahmad Shah Massoud , who became Minister of Defense under Rabbani. General Abdul Raschid Dostum, who defected to the mujahideen shortly before the end of the Najibullah government, also led troops. When Hekmatyar wanted to take Kabul, the troops of Massoud and Dostum came before him and took over most of the ministries. Peace negotiations failed and Hekmatyar's troops, supported by Pakistan, shelled Kabul. The various factions held each other responsible for the fighting.

In addition, tensions escalated in mid-1992 between the radical Sunni Ittihad-i Islami, supported by Saudi Arabia, and the Iranian-supported Shiite Hizb-i Wahdat. The Hizb-i-Wahdat militia entered into an alliance with Hekmatyār in late 1992. Abdul Raschid Dostum and his Junbish-i-Milli militia joined this alliance in early 1994. There were numerous human rights crimes in these power struggles. Human Rights Watch reported that killing in Kabul was practically possible at any time, both artillery fire from Hekmatyar's forces and rival mujahideen factions hit many civilian facilities. There were also numerous kidnappings, looting, rape and murder from various sides of the mujahideen - under Hekmatyar, Massoud, Dostum and other factions. In 1993, for example, there was a massacre in the Afshar district of Kabul by the troops under the warlords Sayyaf and Massoud, in which an estimated 750 people, mainly members of the Shiite Hazara minority, were killed or abducted. By 1993, more than half a million people had fled Kabul. After negotiations, Hekmatyar was appointed Afghan Prime Minister in June 1993. The peace did not last, however, and fighting broke out again between the rival militias in 1994 and 1995.

Origins of the Taliban (1992-1994)

Most of the south of Afghanistan was neither under the control of the central government nor under the control of the militias from the north. Local militia or tribal leaders ruled the south.

The Taliban first appeared in the southern city of Kandahar in 1994. Various sources cite the kidnapping and rape of two girls by a militia leader as the triggering factor, and 30 men led by Mullah Omar to liberate them. The Taliban movement consisted of people who previously fought as mujahideen and continued to be recruited from religious schools for Afghan refugees in Pakistan. Jihad-glorifying propaganda material produced by the USA was also used in schools. The fighting between the mujahideen militias and the hope for peace through a new order gave the Taliban a boost. Their leader and later head of state was Mohammed Omar .

In the autumn of 1994 they made their first military appearance and on November 5, 1994 they took control of the city of Kandahar. Until November 25, 1994, they controlled the city of Laschkar Gah and Helmand Province . In the course of 1994 they conquered other provinces in the south and west of the country that were not under the control of the central government.

Further Taliban offensive and capture of Kabul (1995–1996)

By March 1995, the Taliban had captured six provinces and reached Kabul. At the beginning of 1995, the Taliban held negotiations with both the Rabbani government and the Shiite militia Hizb-i Wahdat, which, however, did not lead to peace. While the Taliban initially lost the battle for Kabul, they continued to advance in the west of the country.

This resulted in a temporary secret alliance between the Taliban and the warlord Dostum (see Afghan Civil War (1989–2001) ). With logistical support from the ISI and new weapons and vehicles from Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, the Taliban reorganized their troops after several defeats in the country and in 1996 also planned a new offensive against Kabul. On September 26, 1996, Defense Minister Massoud ordered the troops to be withdrawn to northern Afghanistan. On September 27, 1996, the Taliban invaded Kabul and established the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan , which was only recognized by Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

War against the United Front (1996-2001)

After the fall of Kabul, the Taliban controlled around 65% of Afghan territory. The disempowered President Rabbani, Massoud and Dostum, former opponents, founded the United Front (known as the Northern Alliance) in response to the Taliban offensives . Massoud was considered the most powerful man in the alliance, and the later President Hamid Karzai joined the United Front . Iran and Russia supported Massoud's troops, Pakistan intervened militarily on the side of the Taliban. According to declassified documents from US authorities ( National Security Archive ), the Pakistani government supplied the Taliban with logistical items such as weapons, fuel and food after it came to power in Kabul in 1996.

In 1997, Northern Alliance troops under Dostum executed 3,000 Taliban prisoners in and around Mazar-e Sharif. The Taliban advanced further north and in 1998 even carried out a hunger blockade against the Shiite Hazara, which led to a diplomatic crisis with the Iranian government. In the offensive of 25,000 Taliban fighters against the remnants of the Northern Alliance in 2001, an estimated 10,000 Islamist militiamen from Arab countries, Pakistan and other Asian countries such as Uzbekistan were also active. On September 9, 2001, two Arab suicide bombers posing as journalists detonated a bomb hidden in their video camera while interviewing Massoud in Takhar, Afghanistan. Massoud died a little later from his injuries.

After the attacks by al-Qaeda on US embassies in August 1998 and the refusal of the Taliban to extradite Osama bin Laden , several UN resolutions against the Taliban were passed between the end of 1998 and 2001. These included an arms embargo and the freezing of Taliban assets abroad.

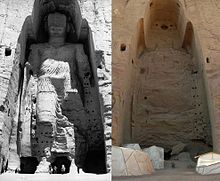

The Taliban enforced their political and legal interpretation of Islam in the areas they controlled. The women lived under house arrest. In the course of the fighting, the Taliban became further radicalized and carried out radical measures directed against non-Muslims. On March 10, despite enormous protests, they destroyed the Buddha statues in Bamiyan with explosive charges and artillery shelling, including in the Islamic world . According to a United Nations report, the Taliban committed systematic massacres of civilians while trying to consolidate control in western and northern Afghanistan. This resulted in a massacre in Mazar -e Sharif and the villages of Bedmushkin and Nayak. According to Amnesty and HRW, both the Taliban and the Northern Alliance troops showed no consideration for civilians when they bombarded Kabul.

September 11, 2001

Two days after the assassination of Massoud, terrorist attacks took place in the United States, which resulted in the deaths of at least 2,993 people and which are considered to be mass terrorist murder .

Four airliners were hijacked in the early morning of September 11th. Two were directed into the towers of the World Trade Center (WTC) in New York City and one into the Pentagon in Arlington , Virginia . The fourth plane, probably with another target in Washington DC, crashed the hijackers against the violently resisting passengers at 10:03 a.m. over the town of Shanksville , Pennsylvania . Around 15,100 of around 17,400 people were evacuated in time for the WTC towers to collapse.

The US identified members of al-Qaeda, based in the Taliban emirate and allied with the Taliban, as the perpetrators of the attacks.

Operation Enduring Freedom (October 2001)

After the attacks of September 11, 2001, the UN Security Council reaffirmed the right to self-defense in the United States in resolution 1368 of September 12, 2001. According to the US and other governments, this legitimized a military operation in Afghanistan under international law . On September 19, 2001, the UN Security Council called on the Taliban government in Afghanistan to extradite Osama bin Laden "immediately and unconditionally," referring to UN Resolution 1333 of December 2000. Also US President George W. Bush asked the government in Afghanistan in a speech to the US Senate to extradite bin Laden: "They will extradite the terrorists or share their fate." Mullah Omar and Abd al-Salim Saif, Taliban ambassadors in Islamabad, said the Taliban would consider extradition if presented with evidence of bin Laden's involvement in the attacks. The US had urged the Taliban to extradite bin Laden about 30 times since 1996 and intensified its efforts in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on US embassies in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi in August 1998. The US provided the Taliban with a dossier containing evidence against bin Laden Involvement in the attacks in East Africa, but the Taliban again refused. The FBI had obtained evidence of bin Laden's involvement from interrogations of the main defendant Mohammed al-Owhali, who had completed combat training in Afghanistan and made a comprehensive confession. He was sentenced to life imprisonment by a US federal court in May 2001. Immediately after the 9/11 attacks, ISI director Mahmud Ahmed flew to Kandahar to negotiate extradition with Mullah Omar. At the same time, Robert Grenier, the CIA representative in Islamabad, met with Taliban commander Mullah Akhtar Usmani in Quetta . Both initiatives were unsuccessful. Ultimately, Mullah Omar refused to extradite bin Laden, partly because he believed the Americans would not send ground troops into the country. In addition, extradition would have proved difficult in practice because bin Laden had a well-armed and loyal protection force and the Taliban did not know exactly where he was at the time.

From October 7, 2001, the United States intervened militarily in Afghanistan with Operation Enduring Freedom . They initially supported ground troops of the United Front (Northern Alliance) in a major offensive against the Taliban with massive air strikes . In the months that followed, the Taliban regime in Afghanistan was overthrown (see also the war in Afghanistan ). The Taliban leadership around Mullah Omar fled to Pakistan.

Taliban fighters caught in fighting and people suspected of supporting the Taliban have since been imprisoned. Most of them were held by NATO troops in internment camps within Afghanistan. Inmates classified as harmless were released. Until autumn 2004, some prisoners were also transferred to the internation camps in Guantánamo Bay , Cuba, which were criticized internationally .

Under the auspices of the United Nations, a transitional government was formed in Afghanistan in 2003, which was supported by UN-mandated foreign troops ( ISAF ). In 2004, a democratic constitution was passed in Afghanistan , which officially made the country a democratic Islamic republic .

Reform of the Taliban (since 2003)

With the formation of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan , the Taliban revolted in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Pakistan plays a central role in Afghanistan. Although several thousand soldiers of the Pakistani armed forces have been killed in the conflict in Northwest Pakistan in the fight against Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan , Al-Qaida , Lashkar-e-Islam since 2004 , those organizations have the backing of parts of the population in some rural and urban areas Areas of Pakistan. Overall, therefore, Pakistan's policy towards the Taliban is not free of contradictions. For example, some of the Koran schools in Pakistan are training centers for Islamism . One of them is the Dar al-Ulum Haqqania in the 50,000 inhabitant city of Akora Khattak in the Nowshera district . Among other things, many Islamists were and are trained there, who then serve as functionaries for the Taliban.

Since the beginning of 2006, the Taliban, together with the Haqqani network and the Hezb-i Islami Gulbuddin Hekmatyārs, have carried out increased attacks against Afghan civilians and ISAF soldiers . Some villages and rural areas in Afghanistan came under Taliban control again.

A 2010 report by the London School of Economics states that the Pakistani intelligence service ISI has an "official policy" of supporting the Taliban. The ISI finances and trains the Taliban. This is happening even though Pakistan is officially posing as an ally of NATO. The London School of Economics report concludes:

"Pakistan seems to be playing a double game of astonishing proportions."

Amrullah Saleh , Afghanistan's former intelligence chief, criticized:

“We're talking about all these proxies [Taliban, Haqqani, Hekmatyar], but not the master of proxies, the Pakistani army. The question is, what does Pakistan's army want to achieve ...? You want to gain influence in the region. "

The Taliban are targeting the Afghan civilian population in attacks. In 2009, according to the United Nations, they were responsible for over 76% of the victims among Afghan civilians. In 2010, the Taliban were responsible for over three quarters of the civilian deaths in Afghanistan. Civilians were more than twice as likely to be the target of deadly Taliban attacks as Afghan government or ISAF troops.

The Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIGRC) called the targeted attacks by the Taliban against the civilian population a "war crime" in 2011. Religious leaders condemned the Taliban's attacks as a violation of Islamic ethics.

In 2011 human rights groups persuaded the International Criminal Court in The Hague to conduct a preliminary investigation into the Taliban for war crimes .

In 2011, war-like skirmishes between ISAF troops and their opponents also increased in scope and severity.

Initiation of peace talks and renewed dissemination

In June 2011, the US surprisingly confirmed that it was negotiating directly with the Taliban.

“The first 10,000 US soldiers will return to their home country in July. The thing in Afghanistan should come to an end in 2014. After that, the Taliban will largely determine the fate of Afghanistan. In the best case scenario, they will make a very shaky compromise with the forces supported by the West that will keep the country reasonably stable. "

In January 2012, the Taliban announced their readiness to set up an office in Qatar . This should be used for negotiations. To this end, eight Taliban representatives traveled from Pakistan to Qatar at the beginning of 2012, and it was opened in June 2013. They unveiled a plaque reading "Islamic Emirate Afghanistan" at the office and hoisted the Taliban flag on the premises. A few hours after the office opened, the US announced that it would begin direct peace talks with the Taliban in Doha.

The Taliban have been trying to conquer regions in Afghanistan since 2015. In the summer of 2016, up to a third of Afghanistan was no longer under the control of the government.

Russia has supported negotiations with the Taliban since 2015. The greatest security threat for Russia is the Islamic State . According to an expert for Russia, support in the form of arms deliveries was also considered or was in progress until 2017. Russia is also working with China and Pakistan to ensure that Taliban representatives are removed from international sanctions lists. The Afghan government was not invited to the first round of talks on Afghanistan in 2016. In 2017, too, the negotiations were less about advancing a peace process than much more about the interests of the surrounding countries. When the Islamic State expanded in the eastern province of Kunar in the summer of 2018, the regional government and the Taliban cooperated militarily in the region until February 2020, until they had defeated the IS there. The US Air Force also avoided air strikes on the Taliban there at that time. The Taliban resistance, which showed no consideration for civilians, was commanded by Sirajuddin Haqqani in eastern Afghanistan .

From 2014 to 2019, according to the Afghan government, 45,000 soldiers of the Afghan national army were killed in action against groups such as the Taliban and the still existing Islamic State in Afghanistan. According to a US report published in June 2019, the Afghan government was still able to control around 55% of the country at the time.

The peace agreement between the US and the Taliban and its breach

See: War in Afghanistan since 2001: The peace agreement between the USA and the Taliban and its breach

On February 29, 2020, the American special envoy for reconciliation in Afghanistan, Zalmay Khalilzad , and the head of the Taliban's political office in Doha , Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar , signed the Doha Agreement .

At the end of June 2020, the New York Times published US intelligence information from spring 2020, according to which members of the Russian military intelligence had offered the Taliban bounties for the killing of US soldiers and other NATO soldiers in Afghanistan, and in some cases paid them. Arrested Taliban fighters and criminals had made corresponding statements, and large sums of money in US dollars had been seized from Taliban bases. The destabilization action against Western forces in Afghanistan was carried out by the GRU , according to the US intelligence report .

Not a single US soldier died in Afghanistan in 2020 or 2021 fighting the Taliban, as the US largely limited itself to air support for the Afghan armed forces in its fight against the Taliban. However, thousands of Afghan soldiers died fighting the Taliban. The Taliban also calculatedly and deliberately killed progressive politicians, journalists and activists who, contrary to the Taliban's Islamic view, stand for the construction of a diverse, modern society. The Taliban are using the persistently high levels of violence to exert pressure in the peace talks with the Afghan government. In the years from 2016 to 2020, the Taliban killed between around 1,300 and 1,625 civilians annually, according to UNAMA . In addition, between around 2,500 and 3,600 civilians were injured or killed, directly or indirectly, by Taliban IEDs each year .

Capture of Afghanistan in the summer of 2021

In the summer of 2021, the Taliban captured large parts of the country and largely smashed the Afghan National Army (ANA). While tens of thousands of soldiers were killed in the fight against the Taliban in previous years, the ANA faced between 85,000 and 200,000 Taliban fighters in 2021. In previous years, many young Afghans had joined the Taliban. During the 20 years of the war, the latter had gained sympathy among the population due to a growing rejection of the foreign occupiers. Since the Doha agreement negotiated by the US administration under Donald Trump with the Taliban did not contain any provisions on a ceasefire with the Afghan troops, the treaty negotiations led to more attacks on the Afghan military because the Taliban hoped to gain a better negotiating position by gaining territories. The Taliban recruited their fighters and Islamists not only from Afghanistan, but also from Pakistan, where millions of Pashtuns also live, and other countries. In the political leadership of Afghanistan there was no effective strategy against the Taliban, which was able to generate further support in parts of the population in the course of the war and thus infiltrated administrative districts, conquered borders and surrounded the provincial capitals. Other factors that led to the ANA's military defeat are mentioned in the history section of the ANA article .

In terms of foreign policy, the Taliban also achieved successes with the conquest. During the advance, in July, the Taliban's international relations representative, Abdul Ghani Baradar , met with a delegation headed by China's Foreign Minister Wang Yi .

On the other hand, sources within the Taliban movement, independent observers and demonstrations against the Taliban in large cities confirm that the Taliban have personnel problems and thus difficulties in controlling provinces.

organization

Current leadership

According to the Council of Foreign Relations , the Quetta Shura is the governing body of the Taliban, with Hibatullah Achundsada as its leader. Abdul Ghani Baradar , who co-founded the Taliban, acts as bureau chief of the Taliban's political department in Doha and leads international relations for the Taliban. Siradschuddin Haqqani is the head of the Haqqani network and manages the Taliban's finance departments. Mullah Yaqoob is the head of the Taliban's Military Commission, which controls the Taliban's network of commanders. All three named are representatives of Achundzada.

According to Ashraf Ghani , the leadership of the Taliban consists of the Quetta Shura and other schūren named after the Pakistani cities in which they are located: e.g. Miranshah- Shura, Peshawar- Shura. According to Ghani, the Taliban in Pakistan have a deep relationship with the state and an organized system of support: "The Taliban receive logistics there, there are finances, there is recruitment ." However, Ghani received assurance from the Pakistani army chief Qamar Javed Bajwa that Taliban rule is not in the interests of Pakistan. When asked how it could be that Pakistan could persuade the Taliban to negotiate with the USA ( Doha Agreement ) if Pakistan allegedly had no ties to the Taliban, Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan said that 2.7 million Afghan refugees were refugees lived in Pakistan and the state thereby had a "certain influence".

Interim government of the Islamic Emirates of Afghanistan in 2021

Mohammed Hassan Achund was presented as head of government of a transitional government of the Islamic emirate of Afghanistan on September 7, 2021 . Abdul Ghani Baradar has been introduced as his deputy. Sarajuddin Haqqani was presented as Minister of the Interior. Amir Khan Muttaqi was declared foreign minister and Mullah Yaqoob was declared defense minister.

Leadership in the past

The Supreme Shūrā of the founding members of the Taliban consisted of the following members from 1994 to 1997:

- Mullah Mohammed Omar (1960–2013), leader of the faithful and head of the Taliban movement, from September 1996 also head of state of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan

- Mullah Mohammad Rabbani Akhund (1955 / 56–2001), government chairman and deputy head of the Taliban movement

- Mullah Mohammed Ghous Akhund (* 1965), Foreign Minister until June 1997

- Mullah Mohammed Hassan Akhund (* 1958?), Chief of Staff, Foreign Minister before Wakil Ahmad Mutawakil and Governor of Kandahar during the Taliban regime

- Mullah Mohammed Fazil Akhund (* 1967), head of the army corps

- Mullah Abdur Razzaq (* 1966), head of the customs authorities

- Mullah Sayed Ghiasuddin Agha (1960–2003), Minister of Information

- Mullah Khirullah Said Wali Khairkhwa (* 1967), Minister of the Interior

- Maulvi Abdul Sattar Sanani (or: Sattar Sadozai), Minister of Justice

- Mullah Abdul Jalil (* 1961), Foreign Minister from 1997

ideology

overview

The Taliban themselves belong more to the ideological school of the Deobandis , a fundamentalist group headquartered in Deoband, India . Many high-ranking Taliban were recruited into the Koran school in Peshawar , the largest Pakistani branch of the Dar-ul-'Ulum-Haqqania Koran school. The political branch and supporter of the Deobandis schools is the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam party in Pakistan. The US asked the Pakistani government to close these religious schools ( madrasas ). In Pakistan, however, these are not officially registered. In 2007, the Pakistani Ministry of the Interior estimated their number at around 13,500, other estimates put it at 20,000. The relationship between the Sunni Taliban and the Shiite minorities in the country is considered tense, even if there are a few Shiites in the ranks of the Taliban.

In the self-image that a Taliban spokesman conveyed in Doha in 2019, the Taliban are Afghanistan, so they do not see themselves as part of the state, but as the state itself.

oppression of women

During the Taliban's reign in the Islamic emirate of Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001, the Taliban's system became world-famous, particularly for its oppression of women. The declared aim of the Taliban was allegedly to create “a safe environment for women in which their chastity and dignity are inviolable again”. Women have been forced to wear the burqa in public because, as a Taliban spokesman put it, "a woman's face is a source of seduction for unrelated men". Women were banned from working and were no longer allowed to be educated from the age of eight.

According to statements made by a Taliban press spokesman in 2019, there is an understanding that female workers are essential, at least in medical professions. A Taliban press spokesman from Ghazni province commented in the ZDF documentary A Dangerous Mission: On the Road with the Taliban in Afghanistan that girls and women also have a right to education under the Taliban.

Destruction of cultural heritage

The Taliban have deliberately destroyed cultural evidence that they consider un-Islamic. These included the Buddha statues of Bamiyan, listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, as well as Buddhist exhibits in the National Museum in Kabul.

Human rights violations

massacre

According to a 2001 report by the United Nations based on testimony and forensic work on grave sites, the Taliban systematically carried out massacres of the civilian population, especially members of the majority Shiite Hazara ethnic group. The United Nations named 15 massacres between 1996 and 2001, for example in Mazar -e Sharif and the villages of Bedmushkin and Nayak. According to Amnesty and HRW, both the Taliban and the Northern Alliance troops showed no consideration for civilians when they bombarded Kabul.

The Taliban also pursued a scorched earth policy . Many regions were affected and entire cities were torn down. The city of Istalif, in which more than 45,000 inhabitants lived, was z. B. completely destroyed and surrounding agricultural land set on fire. The residents were murdered or driven out.

In early 1998, the Taliban systematically cut off all of central Afghanistan, the Hazara main settlement area, from UN aid deliveries. This hunger blockade of around one million people was the first time in 20 years of war that one of the warring parties had used food as a weapon.

human trafficking

Taliban and al-Qaeda commanders maintained a human trafficking network . They kidnapped women and sold them into forced prostitution in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The Time Magazine wrote: "The Taliban have often argued that their brutal restrictions they have imposed women, only one path were to protect the opposite sex. The behavior of the Taliban during the six years in which they expanded their rule in Afghanistan make these statements a farce. ”During an offensive in the Shomali plains in 1999, the Taliban and Arab and Pakistani al-Qaida militiamen left more than 600 women disappear. They were crammed into buses and vans and never seen again. Time Magazine wrote (here translated from English): “The trail of the missing Shomali women leads to Jalalabad, not far from the Pakistani border. There, according to witness statements, the women were locked up in the 'Sar Shahi' camp in the desert ... Some were transported to Peshawar [Pakistan] ... Others were taken to the bin Laden training camp in Khost. ”Aid organizations assume that many women will go to Pakistan where they were sold to brothels or used as slaves in private households.

Some Taliban fighters refused to participate in the human trafficking. For example, a Taliban commander by the name of Nuruludah declared. For example, that he saw Pakistani al-Qaeda fighters forcing women into a van. Nuruludah and his fighters then freed the women from the van. In another incident, Taliban fighters liberated women from an al-Qaeda camp in Jalalabad.

Oppression of women

After gaining political rule over Afghanistan, the Taliban issued edicts that severely restricted women's rights. They concerned the areas of education , medical care, clothing and behavior in public . From then on, girls were forbidden to go to school. Many schools were closed, after which the girls could only be educated privately, if at all. Women in Kabul were no longer allowed to work and were increasingly sitting on the streets as beggars in burqas. As a result of the wars in Kabul alone around 30,000 women lived as widows without any male relatives, they had little other chance of earning a living than by begging. The following illustrates how life-threatening the restrictions were:

According to the Physicians for Human Rights, 53 percent of the seriously ill in Afghanistan received no treatment. Access to medical care was almost impossible, especially for women. At the time of the Taliban rule in Kabul in the 1990s, there was only one hospital where women were allowed to be treated. There, however, the basic equipment was inadequate, there was a lack of running water, medicines , X-rays and oxygen machines . To be treated, women had to overcome several hurdles: They had to appear in the hospital with a male companion. Since male doctors were forbidden to touch women, they could only be examined to a limited extent. Wearing the burqa was also compulsory during treatment. A simple medical exam or visit to the dentist was largely inefficient as the woman was not allowed to bare. Taliban members were regularly present in the hospitals to monitor compliance with the law. Harsh penalties were imposed when Afghans opposed Taliban laws. Doctors were threatened with beatings, an occupational ban and imprisonment .

Both in the cities and in the country, the hygienic conditions were (and in some cases still are today) at a low level. Public baths, as far as they still existed, were generally no longer accessible to women.

In the cities, the laws hit women particularly hard, as the Western orientation was most pronounced there prior to the Taliban tyranny, and in many cases women were regularly employed and wore Western clothing.

Terrorism against the civilian population

The Taliban also target the Afghan civilian population in a targeted manner. In 2009, according to the United Nations, they were responsible for more than 76% of civilian casualties. In 2010, the Taliban were responsible for more than three quarters of the civilian deaths in Afghanistan. Civilians are more than twice as likely to be the target of deadly Taliban attacks as Afghan government troops or ISAF troops.

The Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIGRC) called the targeted attacks by the Taliban against the civilian population a "war crime" in 2011. Religious leaders condemned the Taliban's attacks as a violation of Islamic ethics.

In 2011, human rights groups prompted the International Court of Justice in The Hague to conduct a preliminary investigation into the Taliban for war crimes.

From 2016 to 2020, the Taliban killed around 1,300 to 1,625 civilians annually, according to UNAMA . In addition, around 2,500 to 3,600 civilians were injured or killed annually, directly or indirectly, by so-called unconventional explosive devices (IEDs) of the Taliban.

In 2021 they killed Khasha Zwan, one of the most famous comedians in Afghanistan.

External support

Traditionally, the Taliban were supported by Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, while Iran, Russia, Turkey, India, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan formed an anti-Taliban alliance and supported the Northern Alliance. After the fall of the Taliban regime at the end of 2001, the composition of the Taliban supporters changed. According to a study by Antonio Giustozzi, in the years 2005 to 2015 most of the financial support came from the states of Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Iran, China, and Qatar, as well as from private donors from Saudi Arabia, from al-Qaeda and, for a short time, from Islamic organizations Country. About 54 percent of the funding came from foreign governments, 10 percent from private donors from abroad, and 16 percent from al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. In 2014, the amount of external support was nearly $ 900 million. Overall, the Taliban's 2020 revenues were estimated at 1.6 billion US dollars.

Pakistan

Until 1994, Pakistan's main client, Gulbuddin Hekmatyār, had failed to secure a Pashtun victory and Pakistan was increasingly looking for alternatives. Since it first appeared in November 1994 in September 1996, the Taliban movement was able to conquer the capital Kabul with massive support from Pakistan and, after taking Mazar-e-Sharif in August 1998, controlled around 80 percent of the country. It is estimated that between 80,000 and 100,000 Pakistanis fought on the side of the Taliban. In 1997/98, assistance to Pakistan was estimated at $ 30 million. Pakistan paid the salaries of the Taliban government, supplying wheat, fuel, ammunition, bombs and maintenance and spare parts for heavy artillery and tanks. Pakistan's Interior Minister Naseerullah Babar called the Taliban “our boys”, but Pakistan officially denied any support.

After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Pakistan officially ended support for the Taliban under pressure from the Bush administration . Unofficially, the Pervez Musharraf government ignored the activities of the ISI and military officers who continued to support the Taliban. The alliance with the United States was highly unpopular in the country and the Taliban resistance was seen by large parts of the population as a fair cause. Musharraf also distrusted the Karzai government and its high proportion of Tajik politicians and the government's good relations with India. In 2004, Pakistan resumed support for the Taliban. The ISI provided the Taliban with financial and logistical support and provided the Taliban with safe havens on the Pakistani side after operations in Afghanistan. The ISI protected Taliban leaders such as Dadullah Akhund , Abdul Ghani Baradar and Akhtar Mansur and provided the Taliban with information on the movements and locations of the Afghan army and NATO forces. Taliban fighters were trained by the ISI to receive treatment for injuries in Pakistani hospitals. Pakistani military posts supported Taliban attacks with artillery fire. In July 2008, the Haqqani network carried out a suicide attack on the Indian embassy in Kabul, in which 58 people were killed. The suicide bomber was trained by Laschkar-e Taiba , who has close ties with the ISI, and recorded communications indicated involvement of ISI officers. US Admiral Mike Mullen described the Haqqani network as the "real arm" of the ISI. The US viewed Pakistan as a close ally and cared little about its ties to the Taliban. The Bush administration gave Pakistan $ 5.3 billion in economic and military aid and an additional $ 6.7 billion in compensation for military operations, and valued Pakistan's role in the arrest of al-Qaeda members. Afghanistan responded to Pakistani support by providing assistance to Baloch separatist movements and to the Pakistani Taliban.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia supported the mujahideen with nearly $ 4 billion between 1980 and 1990 and continued funding even after US support ended in 1992. The Saudis suffered a severe setback when, during the invasion of Iraq in the Second Gulf War, most of the Afghan mujahideen groups they funded, including Gulbuddin Hekmatyār, sided with Saddam Hussein and, as a result, Saudi Arabia's two main clients , Gulbuddin Hekmatyār and Abdul Rasul Sayyaf separated. From July 1996, Saudi Arabia began to support the Taliban with financial resources, vehicles and fuel for the attack on Kabul in order to compensate for the dwindling influence in Afghanistan. The Wahhabi clergy in the kingdom played an influential role in the decision to support the Taliban . The extradition of Osama bin Laden came into conflict with the Taliban, and when Mullah Omar insulted the director of the Saudi secret service Prince Turki, Saudi Arabia withdrew the ambassador from Kabul in September 1998. As a result, there was rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran when, in May 1999 , Mohammad Chātami became the first president to visit Saudi Arabia for the first time in almost thirty years.

Saudi Arabia has supported the Taliban financially since 2008 and has given the funds to Taliban shuras, which were not supported by Iran.

Iran

After the Soviet intervention , Iran only supported the Shiite Hazaras. During the civil war that followed, the conflict with Saudi Arabia intensified and, from 1993, Iran supplied military equipment to mainly Tajik groups that fought against the Pashtun majority and formed an alliance with Russia and the Central Asian republics. After the rise of the Taliban and the fall of Kabul in 1996, military support for the anti-Taliban alliance increased significantly. Relations with the Taliban bottomed out when the Taliban captured Mazar-e-Sharif in August 1998, penetrated the Iranian consulate and shot 11 Iranian diplomats, intelligence officers and a journalist. Iran then mobilized a quarter of a million soldiers on the Afghan border and threatened to invade the neighboring country.

After the fall of the Taliban government at the end of 2001, Iran took part in the first Petersberg Afghanistan Conference in Bonn and, according to US envoy James Dobbins, played a constructive role. This positive atmosphere was severely damaged by George W. Bush's State of the Union Address in January 2002 when he declared Iran part of the " Axis of Evil ". While Iran had good relations with the Karzai government, reports of the discovery of weapons of Iranian origin appeared in 2007. By 2012, Iran had become the Taliban's main supporter along with Pakistan, supplying weapons including Igla surface-to-air missiles, land mines , mortars and sniper rifles . According to Taliban officials, the level of assistance to Iran increased from $ 30 million in 2006 to $ 190 million in 2013. Western observers cited the prevention of a permanent US military presence and the containment of the Islamic State in Afghanistan as motivations for Iran to support the Taliban.

Russia

Russia first began to support the Shura of the North in 2016, but then expanded it to include other Taliban groups. Russia coordinated the aid with Iran and analysts suspect that Russia's motives for supporting the Taliban are similar to those of Iran, because both countries see the Islamic State as a project of Saudi Arabia. A number of reports appeared in the press in 2018 and 2019 that Russia had paid Taliban leaders to attack US forces.

financing

In addition to drug trafficking , the Taliban finance themselves through donations from abroad, the diversion of international aid funds , extortion of protection money and the collection of taxes in the areas they control. In 2012, the Taliban raised about $ 400 million, including over $ 100 million from diverted aid. In 2021, Gregor Gysi from the Die Linke party suggested providing the Taliban with development aid under certain conditions, as a complete suspension of the funds would primarily affect the civilian population.

Drug trafficking

In Taliban-ruled Afghanistan in the late 1990s earned the Taliban on the cultivation of drugs and the smuggling of opium , heroin , hashish and other narcotics agents . The Taliban left the farmers as producers of the raw opium and the “informal sector for further processing” of the same into heroin a free hand and levied taxes on cultivation and trade.

For 1999, the Taliban's drug trafficking revenues were estimated at $ 40 million. Airplanes from Ariana Afghan Airlines were used for the transport . With the Resolution 1267 of the UN Security Council international flights of Ariana Air were banned, the drug smuggling from now on ran overland.

In 2001, before the terrorist attacks on September 11th, the Taliban enforced a rigorous ban on the cultivation of opium poppies in Afghanistan, which resulted in the largest drop in drug production in any country in the world to date.

As a result, opium poppies were only grown in northern Afghanistan, which is not controlled by the Taliban. However, the Taliban continued to trade in inventory opium and heroin. The stop in cultivation led to a “humanitarian crisis” as thousands of smallholders found themselves without an income. By stopping cultivation, the Taliban wanted, on the one hand, to ease the sanctions set out in Resolution 1267 of the UN Security Council. According to a report by the CRS , some members of the US drug fighters suspected it was simply a strategy to drive prices up. Indeed, the price of raw opium rose from an all-time low of $ 28 / kg to an all-time high of $ 746 / kg on September 11, 2001. In the weeks following the terrorist attacks , it fell back to $ 95 / kg, probably because stocks were high Style were sold in the face of an impending invasion.

In 2002 the acreage for opium poppies rose from 8,000 to 74,000 hectares. After the war, the Taliban were in a phase of reorganization. Individual Taliban leaders sold their stocks of opium. Some drug smugglers “invested” in the Taliban.

In the areas controlled by the Taliban, local Taliban commanders often levy a ten percent tax ( uschr ) not only on the sale of raw opium, but also on various other transactions, e.g. B. that of small shops and small businesses. Means of payment can be raw opium or other natural products. If the tax was not paid, violence was reported and, similar to the structures in a mafia , Taliban commanders at village level finance themselves from other mafia-like transactions, e.g. B. tolls, but have to give part of them to the higher-ranking commanders.

Taliban commanders protect the production and smuggling of opium militarily and charge up to 20% of the revenue for this. They do not shy away from armed violence against the state police and sometimes raid checkpoints to guarantee drug convoys free passage. In addition, Taliban commanders are involved in taxation or the operation of up to 60 heroin laboratories.

For 2009, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime estimated the Taliban's profits from the opium trade at $ 150 million, that of Afghan drug traffickers at $ 2.2 billion and that of Afghan farmers at $ 440 million -Dollar.

In 2012 the acreage for opium poppies in Afghanistan was 154,000 hectares and the Taliban continued to finance themselves through drug money.

Donations

The Taliban receive donations from all parts of the world, especially from countries in the Gulf region . According to the US envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan, Richard Holbrooke , exact figures for the donations are difficult to determine from 2009, but the donations are "more important" than the drug trade.

See also

literature

General

- Alex Strick van Linschoten, Felix Kuehn (Eds.): The Taliban Reader: War, Islam and Politics. Hurst & Company, London 2018, ISBN 978-1-84904-809-5 (English).

- Alex Strick van Linschoten, Felix Kuehn: An Enemy We Created. The Myth of the Taliban – Al-Qaeda Merger in Afghanistan. Oxford University Press, New York 2012, ISBN 978-0-19-992731-9 (English).

- Roy Gutman: How We Missed the Story. Osama bin Laden, the Taliban, and the Hijacking of Afghanistan. 2nd edition. United States Institute of Peace , Washington, DC 2013, ISBN 978-1-60127-146-4 (English).

Classic Taliban movement 1994–2001

- William Maley (Ed.): Fundamentalism Reborn? Afghanistan and the Taliban . Hurst & Company, London 1998, ISBN 1-85065-360-7 (English).

- Ahmed Rashid : Taliban. Afghanistan's fighters for God and the new war in the Hindu Kush . CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60628-1 (English: Taliban. The Power of Militant Islam in Afghanistan and Beyond. IB Tauris, London 2010, ISBN 978-1-84885-446-8 ).

- Alberto Masala: Taliban. Trente-deux preceptes pour les femmes ; N&B, Collection Ultima Verba (French).

- Gilles Dorronsoro: Revolution Unending. Afghanistan: 1979 to the Present. Hurst & Company, London 2005, ISBN 1-85065-703-3 (French: La révolution afghane. Des communistes aux tâlebân. Paris 2000. The English translation contains an additional section that deals with events after the US intervention at the end of 2001) .

- Neamatollah Nojumi: The Rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan: Mass Mobilization, Civil War, and the Future of the Region. Palgrave MacMillan, New York 2002, ISBN 0-312-29402-6 (English).

- Robert D. Crews, Amin Tarzi (Ed.): The Taliban and the Crisis of Afghanistan . Harvard University Press, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 978-0-674-02690-2 (English).

- The Taliban's War on Women: A health and human rights crisis in Afghanistan . Physicians for Human Rights, Boston 1998, ISBN 1-879707-25-X , physiciansforhumanrights.org (PDF) (English).

- Abdul Salam Zaeef: My Life with the Taliban. Hurst & Company, London 2010, ISBN 978-1-84904-152-2 (English).

Neotaliban from 2002

- Antonio Giustozzi: Koran, Kalashnikov and Laptop: The Neo-Taliban Insurgency in Afghanistan 2002–2007 . Hurst & Company, London 2007, ISBN 978-0-231-70009-2 (English).

- Antonio Giustozzi: Decoding the New Taliban: Insights from the Afghan Field . Columbia University Press, New York 2009, ISBN 978-0-231-70112-9 (English).

- Antonio Giustozzi: The Taliban at War, 2001-2018 . Oxford University Press, New York 2019, ISBN 978-0-19-009239-9 (English).

- Peter Bergen , Katherine Tiedemann (ed.): Talibanistan. Negotiating the Borders Between Terror, Politics, and Religion. Oxford University Press, New York 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-989309-6 (English).

- Borhan Osman, Anand Gopal: Taliban Views on a Future State , NYU Center on International Cooperation, 2016, cic.nyu.edu (PDF; 880 kB) (English).

- Conrad Schetter , Jörgen Klußmann: The Taliban Complex. Between insurrection and military action. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt 2011, ISBN 978-3-593-39504-3 .

- Conrad Schetter: Talibanistan - The Anti-State . In: International Asia Forum . tape 38 , no. 3-4 . Arnold Bergstraesser Institute , 2007, p. 233-257 , doi : 10.11588 / iaf.2007.38.278 .

- Florian Weigand: Afghanistan's Taliban - Legitimate Jihadists or Coercive Extremists? In: Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding , 2017, doi: 10.1080 / 17502977.2017.1353755 (English).

Web links

- Georges Lefeuvre: Afghan Patriots. The Pashtuns, the nation and the Taliban . Le Monde diplomatique , October 8, 2010

- Michael Pohly: The Friends of the Taliban. Foreign interests in Afghanistan . An Analysis of Society for Threatened Peoples .

- Guido Steinberg: Taliban . Federal Agency for Civic Education , May 6, 2009

- Guido Steinberg, Christian Wagner, Nils Wörmer: Pakistan against the Taliban . (PDF; 176 kB) Science and Politics Foundation , March 2010

- Journeyman Pictures: Massoud's Last Stand on YouTube (Video)

- Barbara Elias: The Taliban Biography. The Structure and Leadership of the Taliban 1996-2002. The National Security Archive, November 13, 2009 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Despite Massive Taliban Death Toll No Drop in Insurgency. July 3, 2016, accessed February 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Andrea Spalinger: The Taliban are again in power in Afghanistan: Who are they? Who is leading them? How are they organized? In: nzz.ch , August 17, 2021, accessed on August 17, 2021

- ↑ See H. Wehr: Arabic Dictionary , Wiesbaden 1968, p. 510.

- ↑ Christoph Scheuermann, Dietmar Pieper: How dangerous is a Taliban emirate? This is what a US security expert says about the future of Afghanistan. In: The mirror. Retrieved August 29, 2021 .

- ↑ After the killing of leader Mansur: Taliban appoint new boss . Tagesschau.de, May 25, 2015.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Blood-Stained Hands. In: hrw.org. May 12, 2015, accessed September 16, 2021 .

- ↑ a b Ahmad Shah Massoud: Afghanistan's Cold Warriors - Qantara.de. In: de.qantara.de. September 9, 2001, accessed September 16, 2021 .

- ^ A b Amin Saikal: Modern Afghanistan: A History of Struggle and Survival . 1st edition. IB Tauris, London / New York 2004, ISBN 1-85043-437-9 , pp. 352 .

- ↑ Matinuddin, Kamal, The Taliban Phenomenon, Afghanistan 1994–1997 , Oxford University Press, (1999)

- ↑ Matinuddin, Kamal: The Taliban Phenomenon, Afghanistan 1994–1997 , Oxford University Press , (1999), pp. 25–6.

- ↑ MMP: Afghan Taliban. In: cisac.fsi.stanford.edu. June 20, 2018, accessed September 16, 2021 .

- ↑ Joe Stephens, David B. Ottaway: From US, the ABC's of Jihad. In: The Washington Post. March 23, 2002, accessed September 26, 2021 .

- ↑ The Taliban In Afghanistan. In: cbsnews.com. August 31, 2006, accessed September 16, 2021 .

- ^ Roy Gutman: How We Missed the Story. Osama bin Laden, the Taliban, and the Hijacking of Afghanistan . United States Institute of Peace, Washington, DC 2008, ISBN 978-1-60127-024-5 , pp. 69–70 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Steve Coll : Ghost Wars. The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001. Penguin Books, New York 2005, ISBN 978-0-14-303466-7 , pp. 14 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Roy Gutman: How We Missed the Story. Osama bin Laden, the Taliban, and the Hijacking of Afghanistan . United States Institute of Peace, Washington, DC 2008, ISBN 978-1-60127-024-5 , pp. 94, 111 (English, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b c d Press Backgrounder: Military Assistance to the Afghan Opposition (Human Rights Watch Backgrounder, October 2001). In: hrw.org. September 11, 2001, accessed September 16, 2021 .

- ^ Documents Detail Years of Pakistani Support for Taliban, Extremists. In: George Washington University . 2007, accessed January 21, 2011 .

- ^ History Commons. History Commons, 2010, archived from the original on January 25, 2014 ; Retrieved January 21, 2011 .

- ↑ Ahmed Rashid: Afghanistan resistance leader feared dead in blast. The Telegraph 2001, 2001, accessed January 21, 2011 .

- ↑ "Rebel Chief Who Fought The Taliban Is Buried"

- ↑ Ahmed Rashid: Taliban. Afghanistan's fighters for God and the new war in the Hindu Kush . CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60628-1 , p. 127, 330 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ The Taliban's War on Women. A Health and Human Rights Crisis in Afghanistan. (PDF) Physicians for Human Rights, 1998, archived from the original on July 2, 2007 ; Retrieved January 21, 2011 .

- ^ A b Edward A. Gargan, Special to the Tribune. Edward A. Ga: Taliban massacres outlined for UN. In: chicagotribune.com. October 12, 2001, accessed September 16, 2021 .

- ↑ a b Document - Afghanistan: Further information on fear for safety and new concern: deliberate and arbitrary killings: Civilians in Kabul. In: amnesty.org. November 16, 1995, archived from the original on July 7, 2014 ; accessed on September 12, 2019 (English).

- ↑ Tribute to the Victims of September 11

- ↑ Hans Joachim Schneider: International Handbook of Criminology: Fundamentals of Criminology, Volume 1 , Walter de Gruyter, 1st edition 2007, ISBN 3-89949-130-0 , p. 802

- ↑ NIST NCSTAR 1: Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster: Final Report , Chapter 8.4.2: Evacuation , p. 188 (PDF)

- ↑ UN Resolution 1333 (PDF; 1.5 MB) UN , December 19, 2000, p. 2 of 7; Retrieved October 14, 2012

- ↑ Spiritual leader refuses to extradite bin Laden. Spiegel Online , September 19, 2001; Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ↑ Whoever is not with us is against us. Spiegel Online, September 21, 2001, accessed March 24, 2020 .

-

^ Joachim Hoelzgen: Assassination attempt in the tea house. In: The mirror. September 15, 2001, accessed March 24, 2020 . Olaf Ihlau, Christian Neef: The charades of the divine warriors. In: The mirror. September 24, 2001, accessed March 24, 2020 .

-

↑ US Pressed Taliban to Expel Usama bin Laden Over 30 Times. The National Security Archive, March 19, 2004, accessed March 24, 2020 . State Department Report: US Engagement with the Taliban on Usama Bin Laden. (PDF) The National Security Archive, July 16, 2001, p. 7 , accessed on March 24, 2020 : “On May 27 [2000], in Islamabad, Undersecretary Pickering gave Taliban Deputy Foreign Minister Jalil a point-by -point outline of the information tying Usama bin Laden to the 1998 embassy bombings (2000 Islamabad 2899). The Taliban subsequently rejected this evidence. "

-

↑ Dead man walking. The Observer, August 5, 2001, accessed March 24, 2020 . Lawrence Wright : Death will find you. Al-Qaeda and the road to September 11th . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-421-04303-0 , pp.

423 (English: The Looming Tower. Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11 . New York 2006.). - ↑ Steve Coll: Directorate S. The CIA and America's Secret Wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Penguin Press, New York 2018, ISBN 978-1-59420-458-6 , pp. 60–61 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Ahmed Rashid: Descent into Chaos. The US and the Disaster in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Central Asia . Penguin Books, New York 2009, ISBN 978-0-14-311557-1 , pp. 77 (English, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Ahmed Rashid: Taliban. Afghanistan's fighters for God and the new war in the Hindu Kush. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60628-1 , p. 338–339 : “Mullah Omar mobilized the Taliban to resist the US and rejected all demands to give up power and hand over Osama bin Laden and the members of Al-Qaeda to the Americans. The Pakistani secret service ISI repeatedly tried to persuade Mullah Omar to extradite bin Laden in order to save the Taliban regime, but he refused, although he knew that the Taliban leadership was deeply divided on this issue and a revolt within its own ranks was quite conceivable. Omar also felt strengthened by the assurance of his supporters in Pakistan and in the Al-Qaida terror network that the US would bomb Afghanistan - which the Taliban could survive - but would never send ground troops into the country. "

- ↑ Alex Strick van Linschoten, Felix Kuehn: An Enemy We Created. The Myth of the Taliban – Al-Qaeda Merger in Afghanistan. Oxford University Press, New York 2012, ISBN 978-0-19-992731-9 , pp. 225 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Eric Schmitt: Afghan Prison Poses Problem in Overhaul of Detainee Policy. In: New York Times online . January 27, 2009. Retrieved March 6, 2009.

- ^ NDR: Pakistan: The Taliban University. Retrieved August 29, 2021 .

- ^ A b Matt Waldman: The Sun in the Sky: The relationship between Pakistan's ISI and Afghan insurgents. (PDF) Accessed December 12, 2010 .

- ^ The Jamestown Foundation: 2010 Terrorism Conference, Amrullah Saleh speech. In: vimeo.com. 2010, accessed on September 2, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Bill Roggio: UN: Taliban Responsible for 76% of Deaths in Afghanistan. In: The Weekly Standard. August 10, 2010, accessed August 10, 2010 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Rod Nordland: Afghan Rights Groups Shift Focus to Taliban. In: The New York Times Online . Retrieved February 13, 2011 .

- ↑ a b c d AIHRC Calls Civilian Deaths War Crime. In: Tolonews. January 13, 2011, archived from the original on October 19, 2013 ; Retrieved January 13, 2011 .

- ↑ a b Ulrich Ladurner: Afghanistan mission: The three mistakes of the West . In: Die Zeit , No. 26/2011; Quote: “The US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates has now confirmed this. Who the US is talking to remains in the dark. It is not a coincidence. Because the Taliban are as efficient as they are complex and shadowy. There is no answer to who represents them, who could even conclude an agreement. "

- ↑ Foreign Mission of the Taliban: An office in Doha. In: taz.de . January 3, 2012, accessed January 10, 2012 .

- ↑ Karzai wants to meet the Taliban for the first time. In: Zeit Online. January 29, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2012 .

- ↑ Taliban on the advance in southern Afghanistan SRF on December 22, 2015

- ↑ Afghan government only controls two thirds of the country . Spiegel Online , July 29, 2016

- ↑ Russia calls on Taliban for peace negotiations Die Zeit from April 14, 2017

- ↑ Will Washington and Moscow come together in Afghanistan? Deutsche Welle on January 23, 2017

- ^ The "Big Game" with the Taliban NZZ on April 14, 2017

- ↑ Christian Werner, Christoph Reuter : In the valley of the warriors. In: The mirror . July 16, 2021, accessed July 26, 2021 .

- ↑ Emran Feroz: Taliban government in Afghanistan: Who is the Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani wanted by the FBI? In: The mirror. Retrieved September 8, 2021 .

- ↑ Attack in Kabul: grenades hit memorial ceremony with top politicians . In: Spiegel Online . March 7, 2019 ( spiegel.de [accessed June 19, 2019]).

- ↑ tagesschau.de: Risk of attacks: New IS strongholds in Afghanistan. Retrieved June 22, 2019 .

- ^ Spiegel Online: Afghanistan: War without End. Retrieved June 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Americans and Taliban sign agreements. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . February 29, 2020, accessed February 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Charlie Savage, Eric Schmitt and Michael Schwirtz: “Russia Secretly Offered Afghan Militants Bounties to Kill US Troops, Intelligence Says” , New York Times, June 26, 2020.

- ↑ Eric Schmitt and Adam Goldman: “Spies and Commandos Warned Months Ago of Russian Bounties on US Troops,” New York Times, June 28, 2020.

- ↑ Susanne Koelbl: Afghanistan: US Secretary of State Antony Blinken snubbed the government in Kabul. In: The mirror. Retrieved March 15, 2021 .

- ↑ tagesschau.de: Afghanistan: Fierce fighting in the Helmand province. Retrieved October 21, 2020 .

- ^ A b c Susanne Koelbl: Afghanistan: US Secretary of State Antony Blinken snubbed the government in Kabul. In: The mirror. Retrieved March 14, 2021 .

- ↑ Susanne Koelbl: Afghanistan: "On the death list". In: The mirror. Retrieved March 30, 2021 .

- ↑ a b AFGHANISTAN ANNUAL REPORTON PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT: 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2021 .

- ↑ a b Attack in Kabul: grenades hit memorial ceremony with top politicians . In: Spiegel Online . March 7, 2019 ( spiegel.de [accessed June 19, 2019]).

- ↑ tagesschau.de: Risk of attacks: New IS strongholds in Afghanistan. Retrieved June 22, 2019 .

- ^ The Taliban explained. Accessed August 17, 2021 .

- ^ Afghanistan's Security Forces Versus the Taliban: A Net Assessment. January 14, 2021, accessed August 17, 2021 (American English).

- ^ The Taliban's terrifying triumph in Afghanistan . In: The Economist . August 15, 2021, ISSN 0013-0613 ( economist.com [accessed August 17, 2021]).

- ↑ Uwe Klußmann: History of Afghanistan: How did the Taliban get so powerful? In: The mirror. Retrieved August 20, 2021 .

- ^ Advance of the Taliban - The Afghan army is helpless - also because of Donald Trump. Retrieved August 20, 2021 .

- ↑ tagesschau.de: Afghanistan: Why it was so easy for the Taliban. Retrieved August 20, 2021 .

- ↑ Thore Schröder: Afghanistan - Airport in Kabul: "Time is running out". In: The mirror. Retrieved August 24, 2021 .

- ↑ Christian Werner, Christoph Reuter: Taliban are spreading again over Afghanistan: The valley of the warriors. In: The mirror. Retrieved August 17, 2021 .

- ↑ Christoph Reuter, Steffen Lüdke, Matthias Gebauer: Afghanistan: How the Afghan army could collapse so quickly. In: The mirror. Retrieved August 16, 2021 .

- ↑ Georg Fahrion: Beijing's Interests in Afghanistan: How China Reacts to the Triumphant Advance of the Taliban. In: The mirror. Retrieved August 29, 2021 .

- ↑ Christoph Reuter: Taliban in Afghanistan: In the Dilemma of Triumph. In: The mirror. Retrieved August 29, 2021 .

- Jump up to power in Afghanistan: What is known about the leaders of the Taliban. August 17, 2021, accessed August 17, 2021 .

- ^ Profiles: Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar . February 17, 2010 ( bbc.co.uk [accessed August 17, 2021]).

- ↑ Ramy Allahoum: Taliban sweeps through Afghan capital as president flees. In: Al-Jazeera. Accessed August 15, 2021 .

- ↑ We know that about the leaders of the Taliban. Retrieved August 15, 2021 .

- ↑ Susanne Koelbl: Afghanistan's President Ashraf Ghani: "I know, I'm only a bullet away from death." In: The mirror. Retrieved May 14, 2021 .

- ↑ Susanne Koelbl: Pakistan's Prime Minister Imran Khan: "India is a fascist state, inspired by the Nazis". In: The mirror. Retrieved August 24, 2021 .

- ↑ Afghanistan: Mohammed Hassan Achund becomes head of the Taliban government. In: The mirror. Retrieved September 7, 2021 .

- ↑ AFP | Reuters: Taliban appoint Mohammad Hasan Akhund as leader of 'acting' govt. September 7, 2021, accessed September 7, 2021 .

-

↑ Ahmed Rashid: Taliban. Afghanistan's fighters for God and the new war in the Hindu Kush. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60628-1 , p. 391–399 ( limited preview in Google Book search). Barbara Elias: The Taliban Biography. The Structure and Leadership of the Taliban 1996-2002. The National Security Archive, November 13, 2009, accessed September 26, 2021 .

- ↑ Bismellah Alizada: What peace means for Afghanistan's Hazara people ( English ) aljazeera.com. September 18, 2019. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- ↑ Sophie Mühlmann: Since the Taliban copied IS, hatred has escalated . welt.de. November 2015.

- ↑ Florian Guckelsberger, Leo Wigger: Taliban Shuffle ( English ) magazine.zenith.me. May 7, 2020. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- ↑ a b Afghanistan and the Taliban: Not with them and not without them Audio from SRF International from November 23, 2019

- ^ Nancy Hatch Dupree: Afghan women under the Taliban . In: William Maley (Ed.): Fundamentalism Reborn? Afghanistan and the Taliban . Hurst & Company, London 1998, ISBN 1-85065-360-7 , pp. 145-166 .

- ↑ MJ Gohari (2000). The Taliban: Ascent to Power . Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-579560-1 pp. 108-110.

- ↑ A Dangerous Mission: On the Road with the Taliban in Afghanistan. In: ZDFheute Nachrichten. Retrieved on April 22, 2021 (German, the press spokesman's statement can be found at 4:10 minutes).

- ↑ Kamal Hossain: Situation of human rights in Afghanistan. United Nations, September 26, 2001, accessed August 16, 2021 .

- ^ A b Re-Creating Afghanistan: Returning to Istalif. In: NPR. Retrieved August 1, 2002 .

- ↑ Larry P. Goodson: Afghanistan's Endless War. State Failure, Regional Politics and the Rise of the Taliban . University of Washington Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-295-98111-6 , pp. 121 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Angelo Rasanayagam: Afghanistan: A Modern History . IB Tauris, London 2005 ISBN 978-1-85043-857-1 , p. 155

- ↑ a b c d e f g Lifting The Veil On Taliban Sex Slavery. In: Time Magazine . Retrieved February 10, 2002 .

- ↑ Federal Agency for Political Education, B 3-4, 2001 (PDF; 66 kB) Renate Kreile: The Taliban and the question of women - a historical-structural perspective

- ↑ tagesschau.de: Afghanistan: murder of a "voice of truth". Retrieved August 15, 2021 .

- ↑ Ahmed Rashid: Taliban. Afghanistan's fighters for God and the new war in the Hindu Kush . CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60628-1 , p. 21–22 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b Antonio Giustozzi: The Taliban at War, from 2001 to 2018 . Oxford University Press, New York 2019, ISBN 978-0-19-009239-9 , pp. 260 , 270 (English).

- ↑ Antonio Giustozzi: The Taliban at War, 2001-2018 . Oxford University Press, New York 2019, ISBN 978-0-19-009239-9 , pp. 243–245 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ FRUD Bezhan: Taliban's expanding 'Financial Power' Could Make It Impervious' To Pressure, Confidential Report Warns. Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty , September 16, 2020, accessed September 19, 2021 .

- ^ William Maley: The Afghanistan Wars . 3rd Edition. Red Globe Press, London 2021, ISBN 978-1-352-01100-5 , pp. 175-177 (English).

- ↑ Ahmed Rashid: Taliban. Afghanistan's fighters for God and the new war in the Hindu Kush . CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60628-1 , p. 50–56, 281–282, 297 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b Carter Malkasian: The American War in Afghanistan. A history . Oxford University Press, New York 2021, ISBN 978-0-19-755077-9 , pp. 121–123, 167–168 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Seth G. Jones : In the Graveyard of Empires. America's War in Afghanistan . WW Norton, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-393-33851-5 , pp. 266–267 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Steve Coll : Directorate S. The CIA and America's Secret Wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan . Penguin Press, New York 2018, ISBN 978-1-59420-458-6 , pp. 308–309 (English, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Vahid Brown, Don Rassler: Fountainhead of Jihad. The Haqqani Nexus, 1973-2012 . Oxford University Press, New York 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-932798-0 , pp. 1 (English, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Carter Malkasian: The American War in Afghanistan. A history . Oxford University Press, New York 2021, ISBN 978-0-19-755077-9 , pp. 306–307 (English, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Ahmed Rashid: Taliban. Afghanistan's fighters for God and the new war in the Hindu Kush . CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60628-1 , p. 300 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Steve Coll : Ghost Wars. The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 . Penguin Books, New York 2005, ISBN 978-0-14-303466-7 , pp. 233 (English, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Ahmed Rashid: Taliban. Afghanistan's fighters for God and the new war in the Hindu Kush . CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60628-1 , p. 302–303 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Ahmed Rashid: Taliban. Afghanistan's fighters for God and the new war in the Hindu Kush . CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60628-1 , p. 305–307, 311 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Steve Coll : Ghost Wars. The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 . Penguin Books, New York 2005, ISBN 978-0-14-303466-7 , pp. 414–415 (English, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Antonio Giustozzi: The Taliban at War, 2001-2018 . Oxford University Press, New York 2019, ISBN 978-0-19-009239-9 , pp. 199 (English, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Ahmed Rashid: Taliban. Afghanistan's fighters for God and the new war in the Hindu Kush . CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60628-1 , p. 301 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Ahmed Rashid: Taliban. Afghanistan's fighters for God and the new war in the Hindu Kush . CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60628-1 , p. 303–305 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Ahmed Rashid: Taliban. Afghanistan's fighters for God and the new war in the Hindu Kush . CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60628-1 , p. 308–309 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Ahmed Rashid: Taliban. Afghanistan's fighters for God and the new war in the Hindu Kush . CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60628-1 , p. 122–123, 299, 309–311 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ William Maley: The Afghanistan Wars . 3rd Edition. Red Globe Press, London 2021, ISBN 978-1-352-01100-5 , pp. 256 (English).

- ^ A b William Maley: The Afghanistan Wars . 3rd Edition. Red Globe Press, London 2021, ISBN 978-1-352-01100-5 , pp. 258-259 (English).

- ↑ a b Carter Malkasian: The American War in Afghanistan. A history . Oxford University Press, New York 2021, ISBN 978-0-19-755077-9 , pp. 427 (English, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Antonio Giustozzi: The Taliban at War, 2001-2018 . Oxford University Press, New York 2019, ISBN 978-0-19-009239-9 , pp. 141, 153–154 (English, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Roy Gutman: How We Missed the Story. Osama bin Laden, the Taliban, and the Hijacking of Afghanistan . 2nd Edition. United States Institute of Peace, Washington, DC 2013, ISBN 978-1-60127-146-4 , pp. 305 (English).

- ↑ Antonio Giustozzi: The Taliban at War, 2001-2018 . Oxford University Press, New York 2019, ISBN 978-0-19-009239-9 , pp. 210–211 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Antonio Giustozzi: The Taliban at War, 2001-2018 . Oxford University Press, New York 2019, ISBN 978-0-19-009239-9 , pp. 253 (English, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Carter Malkasian: The American War in Afghanistan. A history . Oxford University Press, New York 2021, ISBN 978-0-19-755077-9 , pp. 428 (English, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Taliban earn 400 million dollars within one year In: Süddeutsche Zeitung, September 12, 2012.

- ↑ WORLD: With conditions: Left wants to make offers of help to the Taliban . In: THE WORLD . August 12, 2021 ( welt.de [accessed August 13, 2021]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Peters 2009 (PDF; 808 kB) Gretchen Peters: How Opium Profits the Taliban, United States Institute of Peace, 2009.

- ↑ a b International Crime Threat Assessment 2000 International Crime Threat Assessment, 2000.

- ↑ a b c Perl 2001 (PDF; 48 kB) Raphael F. Perl: Taliban and the Drug Trade, CRS Report for Congress, 2001.

- ↑ a b c Mansfield 2008 ( Memento of February 12, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 481 kB) David Mansfield: Responding to Risk and Uncertainty, A Report for the Afghan Drugs Inter Departmental Unit of the UK Government, 2008.

- ↑ a b c The Global Afghan Opium Trade. (PDF; 8.5 MB) In: unodc.org UNODC, 2011 (PDF; 8.9 MB).

- ↑ Afghanistan Opium Survey 2012. (PDF) In: unodc.org Summary Findings, UNODC, 2012 (PDF).

- ↑ UNODC 2012.

- ↑ a b USA suspect donors of the Taliban in the Gulf States . Spiegel Online , July 28, 2009.