Silver fleet

The Spanish Silver Fleet ( Spanish Flota de Indias ) is the name given to the convoy , in which merchant ships from the 16th to the 18th century usually made convoy voyages to Central and South America and back to Spain twice a year, accompanied by warships . The fleet transported everyday goods to America on the way there. On the way back, in addition to the income from the colonies in America (especially silver), income from the Philippines and trade goods from East Asia were transported that had been brought across the Pacific Ocean and then by land to the Atlantic.

Origin and composition of the fleet

As early as the first years of the 16th century, Spanish merchant ships sailing to America had come together in associations. To be better protected, they were escorted by privately financed armed galleons . This is how the Carrera de las Indias system came about . On July 16, 1561, King Philip II ordered that two fleets should leave for the colonies each year. Ships on the American route were only allowed to sail from Seville (later from Cádiz ) and only in the fleet. From 1538 onwards, only citizens of Castile were allowed to take part in the American trade and travel to America; from 1620 this regulation was relaxed somewhat.

Merchant ships

The merchant ships belonged to private owners who had to be citizens of the Kingdom of Castile. This regulation was often circumvented by the fact that foreign shipowners acted through Castilian straw men . Since the goods to be carried on the outward journey were much more bulky than the precious metal on the return journey, mature ships were often used for discarding the outward journey; the fleet consisted of an average of 73 ships on the way there and 50 ships on the way back. Various merchant ships were occasionally equipped with up to twelve cannons and often had infantry soldiers on board. The captains performed their service on behalf of the traders, but with a captain's license from the Casa de la Contratación .

Warships

The command of the entire fleet was held by a captain general, who was primarily a soldier and not necessarily a seaman. The captain-general's flagship , the Capitana , led the convoy, followed by the Almiranta , the admiral's ship. The admiral too had a military and not necessarily a nautical career behind him. In addition to the sailors and the artillerymen necessary to operate the cannons, a contingent of around 30 infantry soldiers each was stationed on both ships . Most of the silver and gold treasures were transported on these warships. The captain general and the admiral were appointed by the king before each voyage and paid by the crown. In addition, one or two news ships (Pataches) accompanied the convoy . These were small, fast ships that drove ahead and checked whether foreign ships were approaching the convoy; in addition, they also announced the fleet in the port of destination.

Casa de Contratación

The Casa de Contratación was the onshore part of the administration of the silver fleet. By decree of the Catholic Kings , the Casa de Contratación was founded on February 14, 1503 in Seville . After two centuries it was moved to Cádiz by a decree of King Philip V of May 8, 1717 .

The Casa de la Contratación determined which ships took part in the convoy to America. The helmsmen and captains of the merchant ships of the convoy were trained by the Casa de la Contratación and only got their patents through this institution. The necessary nautical charts for the trips to America were created by the employees of the Casa de la Contratación , kept up to date and passed on to the responsible persons. Legal disputes that arose from trade relations with the American colonies were decided by a special court of the own organization. The Casa de la Contratación checked the cargo on the basis of the loading lists when the fleet left and when it entered and collected the due duties and fees; it also ruled on the authorization of persons to trade with America or to emigrate to America.

The routes of the fleets

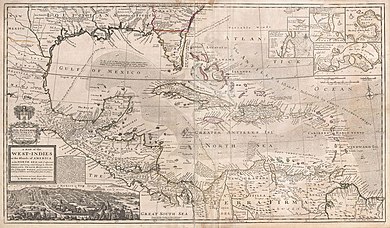

The start and end port of America's voyages ( Carrera de Indias ) was initially Seville, later Cádiz. The fleet used the different ocean currents : Canary Current - North Equatorial Current - Florida Current and Gulf Stream to get from Spain to America and back again on a circuit. The dates for the America voyages set in the orderly of King Philip in 1561 could not be kept due to the weather and wind conditions as well as frequent delays in the loading process. The delays meant that the fleet got into the dreaded time of storms. In 1564 a new regulation was created; this provided that the New Spain fleet (Flota de Nueva España) set off in March or April, the mainland fleet (Flota de Tierra-Firme) in August or September.

The route of the New Spain fleet

The "New Spain Fleet" sailed from Seville to the south of the Greater Antilles and sent individual ships there; their destination was Vera Cruz in the Gulf of Mexico , whose port was protected by the fortifications on San Juan de Ulúa ; construction began in 1565. The trip across the ocean took around three months. After unloading the goods, which were mainly intended for Mexico City , the ships usually wintered in Veracruz. During this time the ships were loaded with the precious metals extracted in Mexico, but also with other merchandise produced in America; In terms of value, however, these made up only a small part. In 1594 z. B. the value of silver was 95.5% of the total value of the cargo, in the period between 1747 and 1778 it was 77.6%. In Veracruz, the fleet also took over the cargo that the Philippines galleon had unloaded from the colony in Acapulco and which had been brought overland from the Pacific to the Atlantic Ocean. To a large extent, these were goods that had been exchanged for silver in East Asia . (The value of these goods is not included in the percentages given above.)

The route of the mainland fleet

The “mainland fleet” ( Tierra-Firme , Galeones ) landed in Cartagena (Colombia) and had its terminus in Nombre de Dios (Panama) , since 1593 in Portobelo on the Isthmus of Panama . The cargo was carried overland with llamas and mules to the Pacific coast and from there again with the ships of the Armada del Mar del Sur to the port of Callao . The cargo was then brought back to Potosí with llamas and mules . Most of the silver was mined in Potosí and some of it was already minted in coins. The silver was transported in exactly the opposite direction.

The collection point for both fleets was in the spring ( Havana ). The time for the return journey was more than four months.

The route of the Asian fleet

The Philippines was a Spanish colony from 1569 to 1898. The " Manila Galleon ", named after the capital, was not part of the silver fleet, but brought a large proportion of the cargo to the silver fleet to America. This galleon transported silver from America to Asia and on the way back silk , spices , porcelain and other products to Acapulco or Panama City that had been produced and traded in China or the Philippines. From Acapulco the goods were transported overland to Veracruz, from Panama to Portobelo . This Asian fleet consisted mostly of only one, occasionally up to three galleons armed with cannons, which sailed from Manila to Acapulco and on to Panama; from there it went back to Acapulco and on to Manila.

Cargo of the fleet

Cargo of the fleet on the way to America

The cargo consisted of goods from various traders. On the way to America, the cargo on the ships consisted of everyday necessities. Since no manufactories were allowed to be established in the colonies , equipment had to be imported. B. were necessary for sugar production. Some of these goods did not come from Spain, but were brought to Spain from Germany, Holland or Italy. Vines were not allowed to be planted in the colonies either, so part of the cargo consisted of wine and brandy . The found in America mercury that the extraction was used for silver, not enough to meet the demand. Therefore, mercury was imported from Spain. It usually took three to six months to load the ships.

Cargo of the fleet on the way to Spain

Most of the cargo consisted of American-mined precious metals, primarily silver. The Kronsilber accounted for only 37% of the skilled to Europe precious metal, the greater part came as a private silver . The treasure El tesoro consisted of silver bars, gold bars and coins already minted in America as well as precious stones and pearls. In addition, sugar, cocoa, tobacco, hides, koschenille, indigo, which were made in America, were shipped to Spain. An important part of the cargo were goods that were exchanged for American silver in China and products from the Philippines that were brought to America on the Manila galleon. These were porcelain, fabrics and spices.

Smuggling and fraud

The fraud began with the loading lists of the ships presented to the inspectors of the Casa de la Contratación on departure for America and the data of the seamen and passengers (mostly emigrants). Not only that the merchandise z. Some of the items were incorrectly declared, and the private baggage of fellow travelers usually contained more contraband than declared cargo. The personal data of the passengers were often changed in such a way that the examiners of the Casa de la Contratación (possibly after a financial recognition) raised no objections to the emigration to America. The loading lists that were drawn up in America often did not contain the entire cargo. On the way back from America, the convoy was called by “supply ships” off the Spanish coast, which took over parts of the cargo before the ships entered Seville or Cádiz and could be checked by the officers of the Casa de la Contratación . Officially, 181 tons of gold and 16,887 tons of silver arrived in Spain between 1503 and 1660. If you try to take into account the amounts smuggled and embezzled, you get around 300 tons of gold and 25,000 tons of silver.

Fleet losses

Enemy attack losses

The convoy voyages of the Spanish fleet were set up to repel attacks on the merchant ships. Despite the armed escort, the fleet was attacked several times.

- In 1628 the Dutch privateer Piet Pieterszoon Heyn succeeded in making the biggest pirate attack against the silver fleet off Cuba . Heyn acted on behalf of the West Indian Compagnie (WIC) and stole treasures, the value of which is estimated at 12 to 15 million guilders. At that time, the Netherlands and Spain faced each other as enemies in the Eighty Years War .

- In 1656 a silver fleet consisting of eight ships sailed from Havana towards Cádiz. On September 19, a squadron of the English Navy under Captain Richard Stayner attacked the ships shortly before they had reached their destination. Two Spanish ships were sunk, two ships burned, two ships reached the port of Cádiz, two ships with their cargo could be captured by the English. The English put the value of this cargo at 3 million pounds.

- In 1657 a fleet consisting of nine merchant ships and two warships initially called at the Canary Islands instead of Cadiz . An English fleet of 28 warships under the command of Robert Blake sank the ships in the bay of Santa Cruz de Tenerife . The cargo from the ships had been brought ashore before the attack.

- 1702 attacked an Anglo-Dutch fleet under Admiral Sir George Rooke and Philipp van Almonde in the course of the Spanish War of Succession on the Spanish fleet, which was coming from America in the bay of Vigo . The Spanish fleet consisted of 19 merchant ships, which were to be protected by 23 ships from the French fleet. The booty was given as 1.5 million pounds.

Losses due to natural events

Only a small proportion of the ships fell victim to enemy attacks; far more ships were lost to the forces of nature. In 14,456 crossings between 1546 and 1650, 402 ships were destroyed by storms. With 2,221 crossings between 1717 and 1772, there were 85.

- In 1622 the ship Nuestra Señora de Atocha sank off Florida. This ship became famous for the history of its discovery and the disputes surrounding the raising of the treasure.

- On July 24, 1715, a convoy left the port of Havana with the destination Spain. It consisted of four ships from the New Spain fleet, six ships from the mainland fleet and a French merchant ship. The value of the entire cargo was over 14 million pesos. On July 30, the fleet off Florida got into a storm in which all ships with the exception of the French merchant ship, the El Grifon , were destroyed.

- 17 merchant ships and four war galleons left the port of Havana on July 13, 1733 for Spain. The ships were loaded with gold, silver, leather, spices, tobacco, china and jewels valued at 12 million pesos. Two days after departure, when the ships were off Florida, the commander of the fleet ordered the turnaround because he expected a hurricane. This hurricane came sooner than expected and destroyed all but one of the ships. Since some ships were driven to the coast and stranded in shallow water, some of the crews were able to save themselves. Part of the cargo could also be recovered later.

End of the convoy trips

From 1765 the rigid system of convoy journeys was relaxed. The last fleet left in 1776. The free trade regulations ( Reglamento para el Comercio Libre ) from 1777 permitted free shipping and trade between almost all colonial ports and those of the mother country. The trading monopoly of the cities of Seville and Cadiz was abolished and all ports in Spain were given direct access to the American market. The Casa de Contratación was abolished in 1790.

See also

literature

- Carlo M. Cipolla: The Odyssey of Spanish Silver: Conquistadores, Pirates, Merchants . Wagenbach, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-8031-3594-X .

- Marcelin Defourneaux: Spain in the Golden Age . Philpp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-15-010338-X , p. 299 .

- Horst Pietschmann: The state organization of colonial Ibero America . 1st edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-12-911410-6 , pp. 191 .

- Wolfgang Reinhard : History of European Expansion . tape 2 . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-17-008469-0 , pp. 352 .

- Wolfgang Reinhard: Brief history of colonialism (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 475). Kröner, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-520-47501-4 , p. 376.

Web links

- Juan Tous: El Ataque de Robert Blake a Santa Cruz de Tenerife. 30 de abril de 1657. June 25, 2012, accessed January 16, 2013 (Spanish).

- La Urca de Lima y el desastre del naufragio de 1715. Retrieved January 24, 2013 (Spanish).

- El San Pedro y el desastre del naufragio de 1733. Retrieved January 24, 2013 (Spanish).

Individual evidence

- ^ Carlo M. Cipolla: The Odyssey of Spanish Silver. Conquistadores, pirates, merchants . Wagenbach, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-8031-3594-X , p. 30 .

- ^ Wolfgang Reinhard: History of European expansion . tape 2 . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-17-008469-0 , pp. 102 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Reinhard: Brief history of colonialism . Kröner, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-520-47501-4 , pp. 74 .

- ^ Wolfgang Reinhard: History of European expansion . tape 2 . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-17-008469-0 , pp. 114 .

- ^ Carlo M. Cipolla: The Odyssey of Spanish Silver. Conquistadores, pirates, merchants . Wagenbach, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-8031-3594-X , p. 39 .

- ↑ Marcelin Defourneaux: Spain in the Golden Age. Culture and society of a world power . Reclam, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-15-010338-X .

- ^ A b Wolfgang Reinhard: History of European expansion . tape 2 . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-17-008469-0 , pp. 96 f .

- ↑ El sistema español de flotas. Retrieved January 24, 2013 (Spanish).

- ↑ Marcelin Defourneaux: Spain in the Golden Age . Philpp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-15-010338-X , p. 91 .

- ^ Wolfgang Reinhard: History of European expansion . tape 2 . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-17-008469-0 , pp. 100 .

- ↑ Marcelin Defourneaux: Spain in the Golden Age . Philpp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-15-010338-X , p. 94 .

- ^ Wolfgang Reinhard: History of European expansion . tape 2 . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-17-008469-0 , pp. 108 .

- ^ Wolfgang Reinhard: History of European expansion . tape 2 . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-17-008469-0 , pp. 122 .

- ^ M. Napier Trevylyan: Robert Blake. An Admiralty Naval History Prize Essay for 1924 . In: The Navel Review . The Naval Society, 1925, p. 427 (English).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: Piraterías y Ataques Navales contra las Islas Canarias . Volume III, part 1. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Instituto Jerónimo Zurita, Madrid 1950, p. 186 (Spanish).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: Piraterías y Ataques Navales contra las Islas Canarias . Volume III, part 1. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Instituto Jerónimo Zurita, Madrid 1950, p. 226 (Spanish).

- ^ Antonio García-Baquero González: La Carrera de Indias: suma de la contratación y océano de negocios . Algaida Editores, SA, 1992, ISBN 84-7647-397-4 , pp. 188 ff . after Carlo M. Cipola: The Odyssey of Spanish Silver. Conquistadores, pirates, merchants . Wagenbach, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-8031-3594-X , p. 45 .

- ↑ Nuestra Señora de Atocha, Santa Margarita Spanish Galleons of 1622. Mel Fisher Maritime Heritage Society and Museum, 2008, accessed January 24, 2013 .

- ^ Lowell W. Newton: Juan Esteban de Ubilla and the Flota of 1715. In: The Americas. Volume 33, No. 2, October 1976, pp. 269, 277-280, JSTOR 980786 .

- ↑ La Urca de Lima y el desastre del naufragio de 1715. Retrieved January 24, 2013 (Spanish).

- ^ El San Pedro y el desastre del naufragio de 1733. Retrieved January 24, 2013 (Spanish).

- ^ Horst Pietschmann: The state organization of colonial Ibero America . 1st edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-12-911410-6 , pp. 86 .