Yörük

As Yörüken (pl. Turkish Yörükler or Yürükler , own name: Yörüglää , the German Yörücken , Yürücken or Jürücken ) the members of a group of be oghusisch-Turkish tribes or the tribes called themselves, which now mainly in southern Anatolia live and Hanafi Sunnis.

Ethnogenesis

Most of the ancestors of the Yörük probably immigrated to Anatolia from the 11th century, together with the Oghusian Rum Seljuks, who were related to them . In the wake of the Mongol advance in the 13th century, many Yörük were added. They were cattle nomads and served the Turkish emirs and sultans as the preferred warriors in the conquest of Anatolia , Rumelia and the Balkans . The name Yörük appeared in writing as an administrative term for the Ottomans as early as the 14th century . The Ottoman ruling class traced its own origins back to the Kayı tribe belonging to the Yörük . The Yörük soon lost their military importance to the Ottoman Janissaries ( yeni çeri , "new troop"). They kept their way of life as cattle nomads , known as yörüklük , for centuries. But even under the Ottomans , some of them were forced to settle down .

At the height of the Ottoman development of power in the 16th century, Yörük and the Ottoman troops had reached the entire Ottoman Empire, in the west as far as south-east Europe and east-central Europe. Even after the Ottoman Empire lost its territory, individual Yörük tribes stayed there. For example, in 1986 Yörük dialects were spoken in 65 communities in North Macedonia .

In the course of the 17th century, the Yörük began to organize themselves in small local and kinship groups. The Ottoman government granted them the right to collect taxes themselves and to recruit young Yörük. Administrative units emerged which led to the formation of fixed tribal units (cemaat) and tribal identities. Around 1830 the tribes, which had previously been subject to constant change in their composition, were recorded as aşiret . The individual Yörük were registered at the registration offices under their tribal affiliation until the middle of the 20th century. In 1934 they too had to adopt civil surnames ( Family Names Act ).

Today, most Yörük in villages and towns are settled and go to different professions. Some are partial nomads who only run their high alpine pastures (yayla) in summer , only very few live in tents all year round. Nowadays everyone, including the fully nomads, must be registered in a village or town. They are neither recorded under their tribe name nor as Yörük.

Some Yörük tribes that are still known in Turkey today: Aksığırlı, Avsarlar, Aydınlı, Çakallar, Gaçar, Genc, Güzelbeyli, Honamlı, Karaevli, Karakoyunlu, Karakayalı, Karakeçili, Sarı Ağalı, Sarıhackeli .

Origin of the name Yörük

The designation Yörük / Yürük (dt. "A person who wanders around , wanders") is often traced back to the Turkish yürümk , (in their own language yörümek ) (dt. " Move , march, walk, wander") and could therefore be traced back to the at least originally related to a nomadic way of life. Kurdish nomads, however, do not call themselves Yörük. For nomads, there is also the general name göçebe (from göç , German "emigration, migration") in Turkish . Yörük, logically capitalized as the name of a tribal group in Turkish, would therefore be more of an ethnic name in the sense of a cultural community than the designation of people with a livestock-nomadic way of life and economy. Most Yörük see it that way too.

Settlement areas of semi-nomadic Yörük

Last Yörük operate semi-nomadic Yaylak-pastoralism (traditional transhumance on natural pastures), and their number is part of the modernization steadily. Their summer grazing areas are mainly in the mountains and plateaus between Konya and Antalya , Kayseri and Kahramanmaraş , Gaziantep and Hatay . The winter grazing areas and permanent settlements are usually in the lowlands along the Mediterranean coast. Only around Konya can you find nomadic Yörük in winter.

Yörük identity

The awareness of being Yörük and being committed to yörüklük is shared by semi-nomadic and sedentary Yörük; For them, yörüklük not only means hiking nomadism, but also the entirety of their culture and their way of life in the patriarchal family and tribal association, which remains decisive even after the Yörük have settled down. Because of their yörüklük , the Yörük see themselves indistinctly as an ethnic unit, but for their self- image the family (aile) , the kinship group (sülâle) , the tent community (oba) , the tent group (kabile) and, with restrictions, the tribe (aşiret) of greater importance.

From the outside, many Turks see the Yörük as a last remnant of the Oghusian Turkishness and revere them as “real Turks” (öz Türkler) . There are also Turks who see themselves as Yörük and identify with them without belonging to the Yörük tribes. In social romantic terms, the Yörük are assigned an original, free life without state constraints. A differentiated approach to the yörüklük attempted the “1. yörük-Turkish Congress in Ankara from 8.-9. January 2005 “( Turkish 1. Yörük Türkmen Kurultayı ).

Way of life and economy

Individual Yörük groups and tribes changed their way of life and economy in earlier centuries. Usually fully nomads became semi-nomads and finally settled people . However, there are also examples of settled people having resumed a nomadic way of life or a long-term or short-term change between full and semi-nomadicism. Today the development is accelerating towards a permanent settlement.

Fully nomads

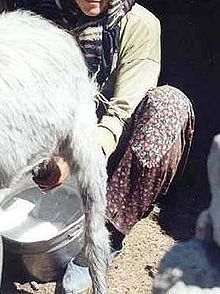

The original migrant cattle breeding of the Yörük must always be seen in connection with arable farming. The fully nomad has trade connections with the farmers, because the fully nomadic Yörük also have grain products as their main diet. Dairy products and meat, wool and fabrics made from wool such as carpets are largely intended for trade.

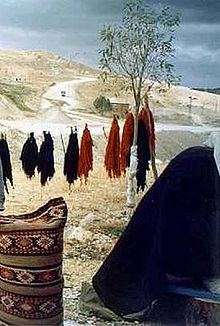

The hikes of the Yörük are determined by the seasons. Summer is spent on the summer pasture areas called yayla in the highlands and mountains, winter in the winter pasture areas (kışlak) of the lowlands and the low elevations of the adjacent mountains. The Yörük live in tents all year round, during the hikes and also in the pasture areas. Soon after immigrating to Anatolia, the Yörük swapped their felt yurts for the lighter black tents made of goat hair that are customary today and made from the Arab world.

Sheep and goats make up the herds of cattle. Dromedaries, horses, and donkeys were previously used as a means of transport. Nowadays they are mostly replaced by trucks and tractors. With dromedaries, the Yörük also took on a wide range of long-distance caravan trade, e.g. B. with the salt of the salt lake Tuz Gölü . Tourist visits in nomad tents with hospitality, folkloric performances and the sale of carpets improve the household budget. One of the main earnings of the Yörük is the sale of sheep and goats, preferably for Islamic holidays such as B. Kurban Bayramı , the festival of sacrifice commemorating Abraham's offering.

Barter dominated in earlier centuries. Above all, the introduction of lease fees for the grazing areas that were free of lease in Ottoman times and more easily accessible, forced the Yörük to switch to a monetary economy. Often enough this led to their impoverishment. Not only in the winter grazing areas, but also on the yayla , fewer and fewer areas are available for grazing due to the expansion of arable farming, the overbuilding with settlements and traffic routes as well as afforestation. The result of these economic developments is a kind of part-time full nomadism.

Semi-nomads

Even with the fully nomadic Yörük, the tent in the main grazing areas was sometimes replaced by simple, solid stone houses. Fixed houses in the winter pasture areas became the rule for the semi-nomads. If part of the family stays in the winter pasture area during the summer, arable farming is carried out here.

Sedentary people

The classic occupation of settled Yörük as a successor to nomadism is agriculture and dairy farming . Especially in the coastal areas of the Mediterranean Sea and in the basin landscapes of the rivers flowing from the Taurus into the Mediterranean Sea, the Yörük take part in the vehement change of the rural subsistence economy to a specialized commercial cultivation for the national and international market.

The descendants of the Yörük can now be found in all professions and branches of business. Most of the time, they still identify with the yörüklük of their ancestors.

language

The Yörük speak an old form of Turkish . Their dialects are almost completely devoid of Arabic and Persian loanwords and reflect traditional life as cattle nomads. Among the Yörük, old Turkish words, idioms and grammatical forms have been preserved, which are mostly not (no longer) used in today's everyday language use of the Turkish population, but are well known (cf. in German the term woman , which is used almost only in dialect finds). Often, however, only the pronunciation of Yörük differs from that of High Turkish. The Yörük dialect often sounds funny or weird to the speakers of High Turkish. It is comparable to something like between Bavarian and High German.

|

|

music

The progressive acculturation of the Yörük in the villages and towns, as well as that of the nomadic Yörük, has led to their special culture and thus also their original music being increasingly suppressed. Turkish pop music can now be heard naturally in the nomad tents, where television sets and CD players have long since found their way. But the Yörük's own music can still assert itself at festivals such as weddings or the circumcision festival.

The Yörük, together with other Oghusian Turkic tribes, brought the tonal element into the music of Asia Minor and Near East, which brought a completely new element to the music, which is mainly dominated by Persian and Arabic: This is particularly evident in the mostly bordoon-like polyphony with which the linear, unison melody is enriched. This polyphony can mainly be achieved on multi-string chordophones.

The long-necked kabak-kemane and the short-necked kemen , also known as tırnak kemençesi (“fingernail kemençe ”) because of their playing style , are ideally suited for drones because of their at least two, usually three, often four strings. This also applies to the widely used long-necked lutes of various sizes with sliding frets, the mostly simplistic saz called bağlama (from bağlamak , dt. " To bind").

The sack pipe tulum ("sack made from a sheep or goat hide") has no drone whistles . It has two chanter that allow a real two-part voice. The open, difficult-to-play kaval longitudinal flute is also a typical shepherd's instrument .

Especially the danced kırık hava , very rhythmic songs with a narrow range, need support from percussion instruments. The big drum davul , popular all over Turkey, dominates here , often in a duo with the zurna , an oboe instrument. These instruments were used by the folk singers of the Alevi Abdal traveling musicians, called Aşık . Some researchers assume that the davul was used especially because of its impressive sound in the pre-Islamic healings of various Turkic tribes. For the Yörük, their use in funeral ceremonies and in the lamentations called ağıt is attested. Osman I introduced the davul as a royal symbol in the Turkish flag and standard.

Other percussion instruments are wooden spoons (kaşık) , the frame drum def and beaker drums , which are listed under different names.

literature

- Halil İnalcık : The Yörüks: Their Origins, Expansion and Economic Role . In: Cedrus , Vol. 2 (2014), pp. 467–495 (English; online [PDF, 418.38 KB]).

- Harald Böhmer: Nomads in Anatolia - Encounters with a fading culture. Remhöb Verlag, Ganderkesee 2004, ISBN 3-936713-02-2 .

- Barbara Kellner-Heinkele: Yörük . In: Encyclopaedia of Islam. CD-ROM edition, XI: 351a. Leiden 2003, ISBN 90-04-11040-2 .

- Peter Alford Andrews, Rüdiger Benninghaus (ed.): Ethnic Groups in the Republic of Turkey (= supplements to the Tübingen Atlas of the Middle East . Series B, No. 60.1). Reichert, Wiesbaden 2002, ISBN 3-89500-297-6 (English).

- Peter Alford Andrews, Rüdiger Benninghaus (ed.): Ethnic Groups in the Republic of Turkey - Supplement and Index (= supplements to the Tübingen Atlas of the Middle East . Series B, No. 60.2). Reichert, Wiesbaden 2002, ISBN 3-89500-229-1 (English).

- Ulla C. Johansen , Douglas R. White: Collaborative Long-Term Ethnography and Longitudinal Social Analysis of a Nomadic Clan in Southeastern Turkey. In: Robert V. Kemper, Anya Peterson Royce (Ed.): Chronicling Cultures. Long-term Field Research in Anthropology. Altamira Press, Walnut Creek 2002, ISBN 0-7591-0194-9 , pp. 81-100, here p. 91 (English; reading excerpt in the Google book search).

- Jutta Borchhardt: From nomads to vegetable farmers: In search of Yörük identity among the Saçıkaralı in south-west Turkey (= Göttingen studies on south-west Turkey. Volume 5). Münster 2001, ISBN 3-8258-4470-6 .

- Albert Kunze (Ed.): Yörük - nomad life in Turkey. Trickster, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-923804-22-9 .

- Albert Kunze: Nomadism in Anatolia - ways of life in the course of history. Master's thesis, University of Tübingen 1987.

Documentaries

- Biljana Garvanlieva: Strange Children: Tobacco Girls. gebrueder beetz film production for ZDF , Germany 2009 (28 minutes; 14-year-old Mümine belongs to the Yörük ethnic minority in Macedonia; video ).