Kaval

Kaval ( Cyrillic кавал ), Bulgarian kawal , Romanian caval , mainly refers to long edge-blown flutes (end-edge flutes), regionally also core gap flutes and generally flutes of different sizes made of wood, which are used in folk music in Turkey and the countries in the Balkans , namely in Bulgaria , Romania , North Macedonia , Albania , Montenegro and Serbia . According to their origin, the rim-blown kaval belong to the type of shepherd's flute, which are spread further east over Armenia ( blul ) to Central Asia ( tüidük of the Turkmen ).

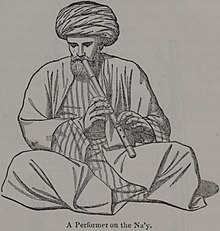

The size of the long one-piece kaval corresponds to the oriental nay used in classical musical styles , which, however, consists of plant cane. Three-part lengthways flutes are also common. In Bulgaria, three-part, rim-blown flutes up to 90 centimeters in length are usually played. In Turkey, in addition to the one-piece, rim -blown flutes ( dilsiz kaval ) from 30 to 80 centimeters in length, magnetic resonance flutes ( dilli kaval ) in similar sizes are part of the musical tradition of shepherds.

As a shepherd's flute, the kaval stands in numerous folk tales in a mythical relationship between pastoralism and the sphere of the divine as well as in a magical connection from the sound of the flute to the human voice to the world beyond.

etymology

In Turkish , kaval not only denotes all types of shepherd's flutes, but also tubes in non-musical contexts, i.e. hollow objects with cylindrical bores such as tubular bones. In a correspondingly comprehensive meaning, kaval occurs in other Western Turkish languages such as Gagauz and Crimean Tatar (shepherd's flute khoval ). Spelling variants are goval and kabal , as the shepherd's flute is called in the Nogaic language . In Azerbaijan has qaval the more important " frame drum " and corresponds Persian daf . Judging by its distribution, the word kaval was evidently formed in Anatolia ; it is derived from the root word * kav, corresponding to * kov, "hollow". The Turkish word composition kaval kemiği (literally "hollow bone") is translated as " fibula " and kaval tüfan (literally "tubular shotgun") as "rifle with a smooth barrel". A parallel to kaval is Latin tibia , which means “shin” and at the same time “flute, pipe”. In Slavic languages is another parallel that of protoslawisch * piščalь, "Whistle, Flute" and "shin", derived word environment to the Polish piszczałka ( "Shin") and piszczel ( "pipe"), Bulgarian Píšťalka (a name the shepherd flute swirka ) and Slovenian piščál (“pipe” and “shin”).

In Turkish , words associated with kaval are kovlik and kovuk (“hollow”) and, in a different meaning derived from them, kavlamak (“[skin or bark] peel off”), kavuk (“bark [that can be peeled off]”) and kavak ( " Poplar ", the bark of which is easy to peel). Kaval occurs in other western Turkish languages, for example as Bashkir kaval ("something hollow"), chatagaisch khaval ("shepherd flute" and "cave, shack, sack, hollow form") and is also used by the Turkmens in Iran. The Greek ghavál, caváli, kavali ("flute") and Romanian caval are derived from Turkish .

Another, frequently repeated attempt to trace kaval back to the Arabic root q – w – l (“speak”, qaul, derived from qawwali , “orator”, from it “herald”, a Sufi singing style) is beyond the linguistic level also in an associative connection with the flute. In many cultures the sound of the flute is considered to be particularly close to the human voice. According to Bulgarian traditional understanding, musical instruments have an expressive capacity analogous to language and have a voice ( glas ). In legends and folk songs, musical instruments with the ability to sing and speak appear. Many Bulgarian songs contain phrases like "kavalut sviri, goviri" ("when the kaval plays, she speaks"). They refer to the magical meaning of the flute as the shepherd's "mouthpiece", to whom it is a lifelong companion.

According to a hypothesis that is dubious because of several intermediate stages, kaval is supposed to derive from the ancient Greek aulos (αὐλός) via kavalos - kavlos - khaulos . The name of the bagpipe tsambouna , which occurs on the Greek islands and which goes back to Italian zambogna , Latin symphonia to ancient Greek symphonia (σύμφωνία), went a comparatively long way through several languages .

Instead of the otherwise usual Arabic names shabbaba and nāy, there is a confusing number of names that differ according to region, size or musical use, including salāmīya, suffāra, baladī and kawal (a) , for the blown edge flutes in Egyptian folk music . In the 1930s, only the longer nāy was distinguished from the shorter salāmīya with six finger holes. In the middle of the 20th century a small flute was called kawal and it was tuned an octave higher than the salāmīya . In addition, kawal and ʿuqla should be the names of flutes that are particularly suitable for playing sad melodies. Today in Egypt a reed-blown reed flute with six finger holes without thumb holes, which is mainly used in the religious music of the Sufis, madīh an-nabawī , to praise the prophet Mohammed , is known as kawala .

Origin and Distribution

Flutes are among the oldest musical instruments and were used in Europe at the same time or earlier as scrapers , buzzers and vessel rattles, probably as early as the Middle Paleolithic . In the beginning there were single-tone flutes , followed by bone flutes and blade of grass flutes with finger holes. The illustration of a longitudinal flute on an ancient Egyptian palette from the second half of the 4th millennium BC. BC, which was found in Hierakonpolis , is put in the context of hunting magic, because it shows the flute player disguised as a fox, how he attracts wild animals. From that time to the legend of the Pied Piper of Hameln , the flute is a magical lure instrument and is used in hunting. In general, flutes are still associated with supernatural ideas to this day; Around Lake Victoria in East Africa alone , flutes (like the ludaya made from a plant stem ) had a bundle of magical tasks: Among other things, they were supposed to make rain, prevent storms, stimulate the flow of milk from the cows and be life-givers for the deified ruler. For an ethnic group of East African cattle herders, the reed flute ibirongwe may only be played by boys and men and has a magical function in some ceremonies (circumcisions). In the Middle East, the flute first appeared among Sumer shepherds around 2600 BC. There and generally in Asia, longitudinal flutes open on both sides have always been in the majority, while in Europe from the Neolithic to the 18th century, core-gap flutes were more common.

Not a specific design, but the anchoring of a society in a pastoral tradition makes its flute a shepherd's flute. Shepherd's flutes are usually easy to make, they are played either solo or in small ensembles. Several single-tone flutes are bundled together to form a pan flute , which is introduced in Homer's epic Iliad as a shepherd's instrument and attribute of the Greek shepherd god Pan . In Greek mythology , the flute connects the pastoral culture with the divine sphere. The Roman poet Ovid takes up both aspects of the flute in the Metamorphoses when he tells of the chaste nymph Syrinx , who flees from Pan, who loves her, and is turned into reeds by the river at her own request. Pan hears the plaintive, sweet sound of the reed and makes a panpipe from unevenly long sections of the reed, on which he blows his songs, carried by the idea of being united with Syrinx.

In Hindu iconography God Krishna is depicted into adulthood with the same flute ( bansi ) with which he beguiled the cowherdesses ( Gopis ) in his childhood . In the classical Indian music played flutes since ancient Indian time exclusively flutes, while in the classic styles of the Islamic Middle East, the end-blown flute Nay prevails. At the geographical transition point in southern Pakistan, the long longitudinal flute narh represents a simple type of flute of oriental origin, which is mainly used for song accompaniment. The distinction common in Turkey between the folk musical instrument kaval and the ney as a flute in art music is not associated with the name. In Iran the ney belongs mainly to classical Persian music ; similar in Arabic music , in which it is distinguished from the shabbaba played in folk music . In Uzbekistan, on the other hand, the small reed flute nay is a shepherd's flute, which in some rural regions together with the jaw harp chang kobus , the long-necked lute dombra and the frame drum doira form the only traditional instruments. In Afghanistan , the shepherd flute nay only of amateur musicians and the jew's harp chang only by women in folk music played.

The oldest images from pre-Islamic times in east Central Asia (in the Kingdom of Hotan ) showing musical instruments are terracotta figures of monkeys, dated to the 2nd or 3rd century, playing flutes, panpipes and other instruments. Other terracottas and paintings in western Central Asia show similar musical instruments including flutes and flutes. From the area of Bactria (in Islamic times Tocharistan ) a silver bowl made in the 7th century has come down to us, which depicts a banquet scene with a monkey playing a flute; a motif that is attributed to Indian influence and already occurred in Sumerian Mesopotamia. A cylinder seal from Ur shows a monkey sitting on a mountain and playing a longitudinal flute. In contrast to the traditional representations, there are far fewer archaeological finds of musical instruments from the same period. The objects found are mainly longitudinally blown bone flutes and clay flutes, for example from the Bundschikat excavation site in Tajikistan . The images show that musical instruments such as harps, lutes and flutes were passed on to China from the Iranian highlands in western Central Asia during the rule of the Parthians up to the middle of the 1st millennium with the spread of Buddhism along the Silk Road .

In the opposite direction, western Central Asia exerted a significant influence on the music of the Middle East from the 11th to the 16th centuries. For example, the uzun hava song, which is characteristic of Turkish folk music in Anatolia, is associated with the singing styles of the Central Asian Turkic peoples and the Mongols : among others with the ut dun of the Kalmyks , the uzun küi of the Bashkirs , the özen küi of the Tatars and also with the hora lungă in Romania. The long, rim-blown shepherd's flutes found in this region include the kaval, the blul in Armenia, the bilûr of the Kurds, the kurai of the Bashkirs, the tüidük of the Turkmen and, like the tüidük , the sybyzgy ( sibizga ) with four to six held between the incisors Handle holes of the Kazakhs .

Apart from this type of flute, overtone flutes that do not have finger holes are considered typical shepherd instruments. In Southeastern Europe these are mainly the tilincă in Romania and the koncovka in Slovakia. The most widespread type of shepherd's flute in Europe are longitudinal flutes with six finger holes made from soft woods ( willow , hazelnut or elderberry branches ) or harder types of wood. In the Balkans they are mostly blown at the edge ( kaval ), there are also some core- gap flutes in Southeastern Europe, including the fujara and the píšťala (generally "flute") in Slovakia and the fluier cu dop , the caval and the double flute fluier gemănat in Romania.

Design and style of play

Romania and Moldova

The music of both countries can be traced back to the Getes and Dacians , whose livelihood was based on agriculture and cattle breeding and who converted to Christianity in the first centuries AD under the influence of Greek missionaries and after the conquest by the Roman Empire . Folk music is largely shaped by the festivals of the Christian annual calendar and a pastoral tradition that has been preserved to this day. In wall paintings on churches, the flute played by shepherds often appears in scenes of the Christmas story , for example in the Church of the Humor Monastery from 1530 and the Doamnei Church in Bucharest from 1683. In Psalm 150 , the faithful are praised by God “with strings and Flute ( caval ) ”prompted.

The flute types in Romania and the Republic of Moldova are generally called fluier ; most belong to the music of the shepherds and peasants and are played by amateur musicians. The shepherds' musical instruments are divided according to their use into signal instruments, especially the wooden trumpet bucium ( similar to the Hungarian one ), and melody instruments. A long notch flute is mainly referred to as a caval , which consists either of a 50 to 90 centimeter long tube made of plane wood with six finger holes or five finger holes arranged in groups of two and three.

In the regions Dobrudscha and Muntenia is caval an open on both sides, three-piece longitudinal flute with eight finger holes in the middle part and four other holes in the lower part, the Bulgarian kawal similar and as a caval dobrogean ( "Dobruja caval ") or caval bulgăresc is known .

Lyrical songs ( doina ) and dances are accompanied by the caval . One of the round dances ( horă ) performed on Sundays is called Hora din caval . In this dance, a violin takes over the part of the flute and approximates its sound to the point of imitation of a voice speaking in a whisper.

Bulgaria

Bulgarian folk music is divided into six cultural regions, some of which developed independently due to the earlier isolation from some mountain regions that were difficult to access and isolated in winter. The country was subject to extensive cultural influence through the five hundred years of Ottoman rule , which lasted from around 1400 until independence in 1908. The nationalist movement of the Bulgarian Revival had a decisive influence on culture , leading to the collection and research of traditional and “national music” ( narodna muzika ). An important representative of this movement was the revolutionary and author Georgi Rakowski (1821–1867), who in his book Pokazalets ( Odessa 1859) was concerned with tracing Bulgarian folk culture products and customs back to an ancient source. At the kawal he emphasized the roots in the pastoral tradition. He praised its practical use as a tool to drive the flock across the pasture and the flute as an expression of the lonely shepherd's longing for his family.

The equation, rooted in popular belief, of the sound of musical instruments and the human voice - the flute plays, so it speaks - contrasts with the practice of music with a strict gender division. Instrumental folk music in Bulgaria is a male affair, while to this day it is predominantly women who maintain the singing tradition. The traditional rural division of labor continues in the music: men wandered with their herds across the pastures, where they played the open lengthwise flute kawal or the magnetic split flute duduk , while cowbells ( zwantsi ) carefully selected according to their pitch sounded. One song says: "He played on a lovely kawal , a silvery zwantsi accompanied him". Women were responsible for the collective fieldwork accompanied by songs and the household. Until the middle of the 20th century, farmers made their own musical instruments.

Design

The most popular melody instruments in folk music are the kawal and the bagpipe gajda . As kawal several shepherds flutes are called. The older type, zjal kawal (цяп кавал), is a one-piece long flute. Today the whole of Bulgaria makes the kawal from three parts: kawal ot tri tschasti (кавал от три части). The three-part kawal with a total length of 60 to 90 centimeters is made on the lathe from plum , cornel or boxwood . Due to the relatively small wall thickness, the wood must have a high level of strength, which is why softwoods are unsuitable. In the past there were long, one-piece shepherd's flutes made of softwood, such as the dzamára in Epirus , but hardwood rods had to be inserted into the tube during transport to protect them from breaking. A second reason why the one-piece long flutes disappeared is that the shepherds were uncomfortable to transport on their wanderings. The high-quality cutting knives that had become common in the craft in the 16th and 17th centuries were required as a technical prerequisite for production, but the handcrafted three-part flute probably only became widespread in the 18th century.

The three-part kawal has seven roughly equidistant finger holes and a thumb hole in the middle part, as well as four further sound holes ( duschnitsi or dyawolski dupki , "devil's holes") in the lower part, which are not covered with the fingers, but improve the sound. The acoustic length is measured up to the first sound hole. The keynote of most Bulgarian kawal is d. With an exemplary length of a d-flute of 64.5 centimeters, the acoustic length is 52 centimeters. The acoustic length determines the lowest note when all finger holes are closed. Divided by the inner tube diameter of 16 millimeters results in the quotient 40. The range of both kawal types (and the three-part core- gap flute duduk, which used to be found in central Bulgaria ) is three octaves with double overblowing . The quotient length: diameter is the measure of the playability of the overtones. The smaller the quotient, the lighter the lower notes, the larger, the easier it is to produce the notes in the upper registers. According to this proportion, Laurence Picken (1975) divides the end-blown Turkish kaval into short flutes with a relatively large inner diameter ( fundamental flutes , "fundamental flutes") and long flutes with a narrow inner diameter ( harmonic flutes , "overtone flutes"). The flute is also called meden kawal ("honey kawal ") because of its warm and soft sound, which the musician creates by blowing in an inclined position . Light-colored rings made of bone, hard plastic or metal are inserted at the connection points, which are intended to prevent the wood from tearing out and, together with incised transverse grooves, serve as decoration.

In addition to the kawal , the smaller core- gap flute swirka is considered a shepherd's flute. Swirka is also the general name for the Bulgarian flute family, which also includes a one -piece double flute called a dwojanka . In the western Rhodopes on the southern border of the country, lengthways flutes played in pairs of the one-piece flute type are called zjal kawal tschift kawàli (чифт кавали). With the flutes, which are always tuned in the same way, one musician plays the melody, the other adds a drone or, less often, follows the melody in unison.

Style of play

In the style of playing typical of all rim-blown shepherds flutes, the player blows a stream of air against the upper beveled edge of the flute tube, which is held down slightly at an angle. In contrast to a core gap flute, it takes a lot of experience to be able to play all tones and sound variants of the flute by changing the blowing pressure, the position of the lips and the inclination of the pipe. With a stronger blowing pressure the player gets into the second or third register. In principle, all tones of the chromatic tone scale can be produced. The only difficulties are the notes D- 1 and D- 2 , for which the lowest finger hole is half covered with the little finger of the lower hand, as well as the notes C 2 and C- 2 . For this the player has to pick up the notes h 1 or d 2 and change the angle of attack.

The low notes sound with a weak blowing pressure, the octaves with a stronger one. A special kind of sound generation of this type of flute is a certain moderate blowing pressure with which a noisy polyphonic sound is generated. The octave and the duodecime can be heard along with the root note . Since the fundamental tone is slightly raised in this blowing technique, i.e. the interval does not exactly correspond to an octave, a specific rough sound is created, which in Bulgaria is designated by the Turkish word kaba (“coarse”, “thick”). The kaba style of playing, which used to be predominantly blown in Bulgaria, corresponded to a sound ideal with which the Bulgarian - like the Turkish - kaval player distinguished himself from the amateur musicians with their high-pitched short magnetic resonance flutes ( düdük ). The “coarse” sound is considered suitable for folk music and only occasionally occurs as a sound effect in ney in classical Arabic music when the musician plays a solo with long notes. In Arabic this way of playing is called muzdawiǧ ("the paired order", because two notes sound together, also the name of a poem). In Turkey, the “coarse” sound of the loud long-necked kaba saz , which is played outdoors, is differentiated from the “thin”, “fine” ince saz , which is played in closed rooms .

The kaba style of playing creates acoustic beats that are important in several musical styles in the Balkans. In Bulgaria this is part of a polyphonic singing style in which one or two singers decorate a melody line and other singers add a beat-rich drone. The ethnomusicologist Gerald Florian Messner (1980) coined the term beat diaphony for this singing aesthetic, which also occurs in southern Albania and Epirus . In Albania, singers are particularly valued when they perform in this way with a “fat voice” (Albanian zë të trashë ). In Greece, folk musical instruments are attested to have a "thick voice" (Greek chondrí foní ), which, like the bagpipe, the cone oboe ( zournás ) and the large cylinder drum ( daoúli ), are suitable for outdoor play.

The music to accompany folk dances is either instrumental or vocal. The singers or male musicians stand in the middle of the dance group. Instrumental ensembles that accompany circular or round dances ( horo , хоро) at weddings consist of several kawal and stringed gadulka or several bagpipes gajda or a kawal and a cylinder drum tapan or a kawal , a gajda and a gadulka, introduced in Ottoman times or a gajda , a kaval and a tapan . As in the entire Balkans, ensembles consisting of two cone oboes zurna and one tapan are popular. With the small Greek-speaking minority of the Sarakatsans on the southern border and with the Wallachians , songs are sung with the accompaniment of the kawal . It was not until the end of the 19th century that folk music ensembles were put together from several (initially two to five) instrumentalists. This was a relief for the musician, who previously had to play long cycles and as loudly as possible at festive events to accompany the dance.

The kawal has traditionally been mainly a solo instrument. Bulgarian historiography emphasizes that even in the “darkest period of Bulgarian history” - meaning the Ottoman rule - the population clung to their own language and traditions. National history was evoked in the 19th century in songs about the Heiducken (lawless gangs who fought against the Turks). The return to the national culture is expressed in changeable forms until today. After the Second World War, the socialist government set up a koledtivi, a folk music collective in almost every village , in which amateur music groups met regularly and always played in traditional costumes. The music of the national minorities usually did not appear at such events. On national holidays, such as September 9, the anniversary of the socialist revolution (1944), children performed folk dances in cities across the country. In Sliven an orchestra with 100 entered on such occasions kawal -Spielern on. At the national folklore festival that takes place every five years in Koprivshtitsa and at comparable events, five instruments, sometimes combined in an ensemble, represent typical Bulgarian folk music: kawal , bagpipe gajda , string gadulka , plucked long-necked lute tambura and cylinder drum tupan .

The internationally best-known Bulgarian kawal player is the jazz musician Teodosij Spasow (* 1961). Stojan Velichkov (Стоян Величков, 1930–2008) played Bulgarian folk music, Christo Mintschew (Христо Минчев, 1928–2012) was a kawal player and voice imitator.

Greece

Due to the resettlement of the Greek population group from southern Bulgaria (former Ottoman province of Eastern Rumelia ) to the northern Greek region of Thrace as a result of the Treaty of Sèvres in 1919, rural musical traditions have been preserved in the regional districts of Serres and Evros , to which the kavali (corresponds to the Bulgarian kawal ), the bagpipe gajda and the cylinder drum daouli ( tapan in Bulgaria ). Many of the Greek refugees who immigrated from Bulgaria, Eastern Thrace and Asia Minor founded new villages in Thrace and continued the tradition of their home region. Until well after the middle of the 20th century, the villages, sealed off by poor transport connections and endogamous marriage rules, retained their own cultural identity with different folk dances, songs and customs. Nevertheless, around the turn of the millennium there were only a few traditional kaval players left in the villages of the Greeks who had immigrated from Bulgaria. The kaval used in the region come from Bulgarian production.

A specialty of the kaval game in Thrace is the legatissimo game, in which almost all notes are strongly tied. Instead of briefly interrupting the flow of air between the notes, short alternating notes are sometimes inserted. This playing technique could have been inspired by the bagpipe gajda , which is always played with an uninterrupted air supply due to its design. From the relatively large range of the kaval , the Thracian musicians mostly only use the tones of the second octave and not all of the semitones. The folk songs played on the kaval are based on a total of six practical guides, two of which have the largest share. The sequence of intervals between these two guides is related to that of the Doric mode and the Turkish makam Hüseyni. This scale is also the most frequently used in all of Greek folk music.

Melodies with gradual progressions, which are often played with glissandi , are typical of the entire folk music of the Balkans as well as Turkish and Arabic music . The melodies in the kaval in Thrace, which also occur in Bulgaria, include above all ordinary trills with the next higher secondary note or with a third interval and double-beat trills , with which long sustaining notes are decorated. In vibrato , the finger that is always stretched and the second phalanx is gently curved in rapid succession so that it stands out from the grip hole. Other regularly used decorations are suggestions and lookups with the neighboring secondary note, as well as Praller and Mordent (one-time short change to the next higher or lower note).

The kaval in Thrace for the descendants of immigrants from Bulgaria embodies the ancient customs of the country. A shepherd's song with flute, called O Tsoutsouliános (“The Lark”) by a musician in Thrace , also occurs elsewhere in the Balkans with a similar content under other names (such as “The Story of the Lost Sheep”). It is about a shepherd who is looking for his lost sheep and plays a melancholy song on the flute. As soon as he sees white stones in the distance, he takes them for his sheep and plays singathistós (a slow couple dance of the Greeks from Bulgaria) for joy . When he gets closer and can't find any sheep, he starts crying again. Eventually God turns him into a bird, a lark, whistling in the sky. So the shepherd is still a lark to this day, who flies around everywhere, whistles and searches for her flock of sheep. The word common in Thrace for "lark", tsoutsoulianós or tsirtsiliágos , probably has an onomatopoeic origin and refers to the constant whistling of this bird. The shepherd's transformation creates a connection between the sound of the flute, the chirping of birds and the human voice on the narrative level. This Thracian version of the story is the only one in which the shepherd does not find his flock again at the end. Daniel Koglin (2002) interprets the sad outcome as a reflection of the old ways of life that have disappeared and the traditional pastoral culture in Greece that has become meaningless.

In Northern Greece, kavali can also be used to denote the split flute souravli ( sourouli, σουραύλι). In some parts of Greece, the general name for Shepherd flutes is floyera , otherwise a short, about 30 centimeters long shepherd flute floyera that was sometimes used for solo dance accompaniment, from the long Kavali (also tzamara distinction). In the second half of the 20th century the shepherd's flutes disappeared from the general public musical life of Greece, replaced by the Klarino (a clarinet with keys ), which originated from the urban music scene and is played together with the violin and accordion. The largely disappeared kavali and floyera have become symbols of what was once traditional shepherd life .

North Macedonia and Serbia

As in Bulgaria, in North Macedonia the kaval is the most popular flute because of its warm tone. The kaval is an obliquely blown open length flute that is made in three sizes with approximately 65, 75 and 85 centimeters. According to other information, the standard lengths are about 69, 71 and 76 centimeters, rarely 82 centimeters. The material used is the wood of young ash trunks , the diameter of which is approximately 5 centimeters. In the traditional method, this is sawn one meter in length from the top of a ten-year-old tree, heated over the fire for three quarters of an hour and pre-dried. The wood is bent straight, clamped horizontally and drilled with a hand drill to an inner diameter of 15, 16 or 17 millimeters. The outside of the tube is thin-walled and smoothed with a knife. The seven finger holes and one thumb hole are oval (6 × × 8 millimeters) drilled at equal intervals, starting with the second hole from the top at half the length of the pipe. The holes made with a sense of proportion result in a non- tempered tuning with non-standardized pitches.

Corresponding to the kaval in Bulgaria, Greece and Albania, the Macedonian kaval have two to four further holes at the far end, the first of which is always made on the underside of the game tube in line with the thumb hole. As in Bulgaria ("Devil's Hole") and Greece, there is a legend according to which the devil, when he first heard the flute play, became jealous and, in order to destroy it, secretly drilled a hole in the underside. This only made the sound of the flute more beautiful and the devil was furious. A more practical explanation is the playing position of the shepherds, who often sit on the floor with the pipe end of a long flute on the floor or on one foot.

The Macedonian kaval is predominantly a solo instrument by amateur musicians and is only sometimes played together with a similar kaval that produces a drone tone. When used in pairs, one flute is considered to be “male” and the other is considered to be “female”. Other shepherds flutes are the šupelka , which is around 30 centimeters long, with six finger holes and the duduk core- gap flute . The rather shrill-sounding šupelka is rare today, but has a longer history that goes back to bone flutes.

The Serbian folklorist Jeremija M. Pavlović presented an unusual instrument classification in 1929 when he assigned the bagpipe gajda and the kaval to the poor, while he described the cone oboe zurla and the drum tapan as instruments of the rich; probably on the assumption that the professional Roma musicians playing with several zurla and tapan at weddings would generate more income than the Macedonian amateur musicians with kaval and gajda . In fact, there is a clear cultural dividing line: Macoedonian Roma musicians never play musical instruments associated with the rural Slavic environment, such as gajda and kaval .

One of the popular beliefs of the Southern Slavs is the idea that all animal and vegetable nature and all things are endowed with senses. It should be possible for people to come into contact with the natural world, which is attempted with magical customs such as the Paparuda or German fertility ceremonies and generally with a method called “silent language” ( nemušti jezik ). With the "silent language", as it is described in stories and songs, primarily all large animals and birds can be addressed, which also communicate with each other in this way. Humans can best reach animals linguistically when they produce certain tones and noises that come close to animal noises. The use of a kaval or the simple reed instrument diple is helpful . The ability to speak silent is given to a person by supernatural beings (god, devil, dragon, snake ruler) in human form. The ancestors from the underworld blow the silent language into the mouth of a shepherd in gratitude for his help or snakes transfer this ability without any action. Someone can transmit silent speech to a shepherd by blowing a kaval in the ears or three times in the shepherd's mouth. Then the shepherd blows back three times. Spitting through a flute is another way that speech can be transmitted to communicate with nature. Similar magical-animistic ideas are common in many cultures around the world.

As in socialist Bulgaria, in the countries of the former Yugoslavia there was state support for national folk culture, which included the construction of folk music with professional or semi-professional music groups. The kind of "ethno-pop" formed in this way was opposed by an international rock music scene from the late 1970s. The disintegration of Yugoslavia into individual states in the 1990s was accompanied by a serious political and economic crisis, which resulted in increasing regionalization and ethnic division in the language and other cultural expressions. It is unusual that at the same time in this situation kaval , which was previously practically unused in Serbia and has a Turkish name that was spread in the Balkans during the Ottoman period, found its way into Serbian music across ethnic borders. In this invention of tradition, the kaval has appeared as the representative of Serbian music since around the year 2000. Before 1990, Serbian musicians only played the kaval in public in a single village in Kosovo on the Albanian-Macedonian border, so far from the centers of the Serbian folk music scene. According to a report from the 1960s, the kaval and the shorter šupelka belonged to the instruments of the Gorans (in the Dragash municipality ). The flutes were played by men as soloists or in pairs, in the latter case the second flute added a drone tone. A singer alternated strophic between flute and singing voice. In Kosovo, the kaval is actually an old shepherd's instrument and can be found on a wall painting in the Serbian Orthodox Church in the village of Drajčići ( Prizren municipality ) from the 17th century. During the socialist period in Serbia practically only kaval players from Macedonia were known, their music was available on phonograms and was broadcast on the radio.

The trigger for the introduction of the kaval applies a movement of visual artists and singers in Belgrade , their unifying doctrine, the unity of the Eastern Christian Church tradition - consisting of icon painting , frescoes and church choral - and the continuity over time of the Ottoman rule to the Byzantine Empire back postulated. Musically, this phenomenon, called “Byzantinism”, is essentially about reviving a Byzantine painting and singing tradition. In 1993 a church women's choir and a men's choir appeared in Belgrade under the name " Johannes von Damascus " with this claim. This phase includes the group's preoccupation with traditional painting methods for church painting and the interest in the kaval awakened by the sound recordings of Macedonian musicians . The play of Macedonian folk tunes and improvisations ( ezgije ) on the kaval initially took place after the regular services in the vicinity of the church and exerted a strong feeling of togetherness in faith in those present.

For the Serbian-Macedonian way of making music, two identical kaval are always made so that they can be played together. One musician plays the melody with the “male” kaval , the second adds a long drone tone with the “female” flute. The drone sound also occurs in other folk music traditions in the Balkans, but particularly characterizes the Macedonian kaval playing , which is connected to Byzantine church chant. With its chromatic tone sequence of almost three octaves, the tonal variation options and tonal fine gradations, the kaval also appears to be suitable for the scales of Byzantine church chant, because the pitch of the kaval can be varied by changing the blowing pressure with the same finger position .

Some Serbian musicians see the flute as a means of religious devotion and declare that the kaval has the ability to speak, which is why their playing becomes a form of prayer for them. Parallels to this are the use of the flute ney in mystical- Sufi rituals in Turkey ( sema , remembrance of God through music) and also playing the flute in other cultic practices. In the Balkans, too, Sufi dervishes used to play the kaval at their religious gatherings, in Sarajevo until the 1960s. The Rifāʿīya- dervishes in Macedonia called their ritually used flute ny . Beyond the music, the (Macedonian) kaval is assigned a symbolic role in the affirmation of the national identity and the foundation of its orthodox tradition in early Christian Byzantium.

In the Serbian-Montenegrin contribution to the Eurovision Song Contest 2004 by Serbian pop singer Željko Joksimović , Lane moje, the kaval appears in mystical exaggeration as the national instrument of Christian Serbia in the opening sequence and prominently near the singer during the entire stage show. With the kaval , which comes from the predominantly Muslim Kosovo, Kosovo is presented as an alleged Serbian heartland. This Eurovision song made the kaval popular throughout Serbia and has since been used frequently in neo-traditional Serbian folk music.

Albania

Some wind instruments belong to the music of the shepherds in Albania , including, apart from the flutes in northern Albania, the zumare (related to the Arabic zummāra ) consisting of two chimes with single reeds and a single bell made of animal horn. Converted into a bagpipe, this instrument is called bishnica or mishnica . In southern Albania folk music, the single reed instrument pipeza and the bagpipe gajde , adopted from neighboring countries , appear. The most common and nationally known name for Albanian longitudinal flutes is fyell , which is also used to designate the long open flute, which is called kaval (or kavall ) in the southern half of the country . In the Labëria region in the southwest, flutes are called njijare or cule. Magnetic gap flutes in the south are called duduk , in the north bilbil or fyelldrejti . Double flutes are Labëria as culedyjare and in northern Albania as binjak known.

According to some shepherds, non-metric melodies from the pastoral tradition performed on the flute are supposed to calm the herds or steer them in the right direction. In addition to this solo play for personal entertainment, flutes are occasionally used in family circles to accompany group dances.

During the Ottoman period, professional musicians, mainly Roma, played in military bands ( mehterhâne ). Other urban music groups of professional musicians organized in guilds ( esnafe ) in the southern Albanian city of Berat consisted of violin , kaval , long-necked lute saz , three-stringed lute jongar and box zither kanun . In Shkodra in northern Albania, a similar vocal and instrumental ensemble consisting of professional male musicians performed for entertainment at social events during the Ottoman period. The ensemble type called aheng played melodies based on Turkish makam (here called perde ) with violin, saz , frame drum ( derf ) and vocals, sometimes expanded to include kaval , clarinet and accordion .

A special flute ensemble exists today in the remote small town of Gramsh . The iso-polyphony cultivated in southern Albania , a form of polyphonic singing, is performed on flutes by 18 to 20 shepherd musicians. The kaval of this ensemble are divided into melody and drone instruments according to the choirs.

Turkey

In Turkey all shepherds flutes made of wood, plant cane, bone or metal (mostly brass) are called kaval , especially the longitudinal flutes open on both sides. The Turkish kaval have five or more finger holes and one thumb hole; With all long Turkish flutes, as with the Bulgarian kawal , the effective oscillation length is not limited by the pipe, but by additional air holes at the lower end. A type of core gap flute with or without a beak mouthpiece is called düdük in Turkey . Other national wind instruments are the cone oboe zurna and the cylindrical double reed instrument mey . Wind instruments that only appear in regional folk music styles are the small bamboo clarinet sipsi in the southern Turkish provinces of Burdur and Antalya , further east in central Turkey the double pipe arghul (also çifte ) and in the Black Sea region in the northeast the bagpipe tulum .

The Ottoman writer Evliya Çelebi (1611 - around 1683) gives in his travel book Seyahatnâme the most detailed description of the musical instruments common in the Ottoman Empire at the time . The kaval (here qawāl ) describes Çelebi as the first musical instrument invented by Pythagoras and played on his wedding night . The flute has nine finger holes and there are 100 flute players in Istanbul. In a 1922 contribution to the Encyclopédie de la musique et dictionnaire du conservatoire published by Albert Lavignac , the Turkish musicologist Râuf Yektâ Bey (1871-1935) declares the kaval to be a very primitive instrument that produces false notes. He explains that the kaval has six to seven finger holes and one thumb hole and is played by Anatolian shepherds in the pasture. The playing position of the flute in the 18th century - unchanged to this day, diagonally downwards to the left - can be seen on a miniature in the handwriting Surname-i Vehbi , which shows a shepherd with a long kaval .

Long shepherd's flutes with blown rim

To distinguish between sound generation, material, size or use, the different types of flutes have an affix to their name. Dilsiz kaval ("silent flute", ie without tongue) or damaksız kaval ("flute without a palate") are all called rim-blown kaval without core gap to distinguish them from the core gap flutes dilli kaval ("with tongue"). A kamış kavalı (“blade of grass flute”) is a flute made of plant cane , including reeds ( phragmites ), ledges ( scirpus ) and hedgehog's cob ( sparganium ). The çam kavalı ("pine kaval") and the madenı kavalı ("metal kaval") are named after the material. As with other types of instruments, cura kavalı denotes a small form of the flute, furthermore orta means “medium (large)” and tam means “complete”, ie large.

The long, one-piece shepherd's flute, which corresponds to the sloping, rim- blown flutes in the Balkans, is known as çoban kavalı (“shepherd's kaval ”) and measures around 80 centimeters. In the province of Burdur, flutes are traditionally often made from juniper , with the Yörük on the southern Mediterranean coast of Turkey also from pear tree or plum wood. One such flute, which was made by the Yörük and is in the ethnographic museum in Adana , is 84 centimeters long and has an inner diameter of 15 millimeters. The first of three sound holes is located 68.8 centimeters from the blow-in opening on the underside, the second on the top is 75.5 centimeters and the third hole on the side is 78.5 centimeters away. If these holes are small in diameter, they change the sound rather than pitch by reducing the overtones .

The Yörük call this flute kuval . It is held at an angle of about 20 ° to the side and with one edge of the mouthpiece between the half-open lips, often up to the almost closed teeth. The wide airflow is directed towards the other edge and can be controlled by changing the angle of attack. The long kaval is mostly overblown so that with a small amount of air the first partial can be heard almost constantly and the second partial can be heard at least occasionally. Here the duodecime sounds stronger than the - slightly raised - fundamental and the octave. The sound image aimed at by musicians, as in Bulgaria, with which the kaval differs from an "ordinary" (nuclear gap ) flute düdük , is called kaval horlatma in Central Anatolia : "the kaval make you snore ". Shepherds playing kaval are encouraged to master this special flute sound because it is used to communicate with the sheep, it is said.

The long one-piece kaval is the most typical shepherd's instrument in Turkey, which is particularly valued by the semi-nomadic Yörük. Many stories deal with the kaval as a signaling instrument to calm down the sheep or goat herds with certain melodic motifs, to round them up or to lead them to another pasture. A shepherd's tale known far and wide in Anatolia by the name of Karakoyun ("black sheep") has the following content: A poor shepherd asks the rich herd owner for his daughter's hand. Rather than flatly refusing, the Lord sets the Shepherd a task he believes cannot be accomplished. The shepherd should only feed his sheep with salt and not give them water for six days. When he then releases her, he should use his flute to prevent her from running to the water because of her great thirst. The shepherd plays such a beautiful melody on the flute that the sheep eagerly listen to her and thereby wins the daughter to be his wife.

Shepherd melodies played on the kaval are differentiated according to use and mood. The Yörük have yüksek hava , “high air / melodies” at a fast pace, which accompany wrestling matches ( yağlı güreş ). Senir havası and aman havası are quieter soulful melodies that are close to the lamentations ( ağıt ). Lamenting melodies ( ağıt hava ) are sung at a slow tempo and played on the kaval in the lower pitch. According to Laurence Picken (1975), the Yörük custom of playing kaval lamentations at the grave of a deceased dates back to pre-Islamic times. The repertoire of the kaval players ( kavalcı ) also includes zeybek havası . Zeybek is a male dance in southwestern Turkey. In the local province of Burdur , the songs otherwise known as uzun hava are known as gurbet havası (“homesick melody”) or as guval havası ( guval from kaval ). In eastern Turkey, near Malazgirt , kaval players are familiar with a melody called bülür . The word refers to the Kurdish flute bilûr and the Armenian flute blul .

In the approximately 80 centimeter long, three-part shepherd's flute ( üç parçali kaval ), the finger holes are in the middle section and the thumb hole is made near the first finger hole. The dimensions are not specified, so that the first sound hole in one specimen (made in Kepsut ) was 2.5 centimeters away from the lowest finger hole and in another specimen (from the Akhisar area ) 9 centimeters away. Both flutes produce a chromatic sequence of notes up to a fifth above the root note without overblowing.

In the past, three-part flutes were often made of wood (boxwood, apricot wood) without a lathe . Simple turning lathes were driven discontinuously by hand with a 90 centimeter long string bow ( yay ) according to the principle of the fiddle drill . The construction was mounted on the floor and the craftsman fixed the turning knife ( arde ) with both feet. Such a lathe was also used to drill out the cantilevered game tube. So equipped workshops for three-part kaval were among others in Ankara , Edirne and Eskipazar .

For kaval made in large numbers on motorized lathes , Gaziantep, the Eminönü district of Istanbul, are traditional manufacturing centers. The province of Gaziantep is the most famous center for the mass production of flutes and reed instruments in Eastern Turkey and supplies the entire Turkish market with musical instruments for shepherds and farmers as well as children's instruments. The regionally available apricot wood is essential for production. The specialty of Gaziantep among the flutes is the kinlı kaval ("flute with scabbard"), which, according to its name, comes with a case. In addition to the seven finger holes and the thumb hole, the kinlı kaval has two sound holes on the side at the lower end. The first (upper) sound hole limits the maximum oscillation length and the second sound hole reduces the sound of the overtones. The second to fifth partial tones are amplified by the narrow cylindrical bore. In conjunction with relatively small finger holes, the result is a soft and fine tone. The wood surface is provided with ring-shaped grooves and a yellowish varnish coating. The sheath made of willow wood is heavily grooved and painted with multicolored rings.

The cura kavalı ("small kaval ") is a shorter version of the çoban kavalı , which was produced in three lengths of 49, 54 and 58 centimeters after 1962 in Gaziantep. The addition to the name cura relates to the 80 centimeter long çoban kavalı , which is the standard for shepherd's flutes . Some shepherds prefer long metal flutes, madeni kaval (“metal kaval ”) or, after the most common metal, pirinç kaval (“brass kaval ”). In a type sold in Istanbul, the diameter of the brass tube is 16 millimeters with a wall thickness of 2 millimeters. According to one report, there were brass flutes 75 centimeters long and 15 millimeters in diameter in Sivas in 1937 .

Core gap flutes

Core gap flutes with finger holes are known in Turkey as dilli kaval ("tongue kaval "), damaklı kaval ("palate kaval "), dilli düdük or just düdük . In Azerbaijan they are called tutek . They are regarded as instruments for inexperienced players, while experienced musicians prefer rim-blown flutes. Two types of flute are distinguished according to their size. One type includes flutes up to 35 centimeters long with a relatively large inner diameter. More common is a type of flute with a relatively small bore, which is 31 to 80 centimeters long and has at least two air holes at the lower end. A short damaklı kaval from the province of Kastamonu is characterized by a protruding protuberance with several turned grooves in the upper third. With a total length of 30.7 centimeters, the flute has an acoustic length of 27.5 centimeters and an inner diameter of 8 millimeters. The thumb hole is located on the bottom opposite the middle between the first and second handle hole, the seventh handle hole is just in front of the lower end. The Turkish core gap flutes usually do not have a beak, but a straight upper end, which is closed with a wooden plug except for a gap as an air channel.

Tokat is a traditional center for the production of long magnetic resonance flutes, which are valued for their high quality . They are made of plum wood and decorated with rings made of boxwood. In addition to full-length instruments, there is a size with 40 to 50 centimeters long flutes ( uzun dilli kaval ), which also have two lower sound holes. These flutes reach the partial tones of the octave by overblowing, but the higher ones only poorly.

A simple type of flute is a short core-gap flute made of a plant tube closed at the bottom by a growth knot with two to five finger holes and a thumb hole. The upper end is bevelled like a beak. A block of willow wood directs the blown air to the cutting edge on the top. This dilli kamış kavalı ("tongue-pipe kaval ") or kamış düdüğü ("pipe pipe") was mainly offered to children. In the 1960s, the reed flute, presumably only made in Hatay Province , was widespread throughout Turkey.

Origin and style of play

Which always made of wood kaval is still one of the traditions of the shepherds, in contrast to the reed flute ney , in the Turkish art music is played and enjoys a reputation as a religious musical instrument since the 13th century the Sufi orders which they Mevlevi in the Ritual music was adopted. However, beyond the different musical uses and other materials, there are connections between kaval and ney. A type of flute made in Gaziantep with a cylindrical wooden tube came on the market as ney and some kaval are made in a defined length, which is related to the traditional length of the ney . The tube for the ney is cut to a length of nine internodes and, as Kurt Reinhard (1984) suspects, divided into 26 sections according to old numerical myths, from which the arrangement of the handle holes results. Such extra-musical relationships, which extend as far as China, point to the old age of the ney .

Laurence Picken (1975) attributes the use of wood in the kaval instead of plant cane, which is abundant in the natural environment of the shepherds, to a Western European influence. It is possible that the Turkish flute makers, with their technical skills at the lathe, wanted to imitate the lavishly decorated flutes that arrived from Western Europe in the 18th century. This is at least to be assumed for the core-gap flutes, of which fewer parallels can be found in the neighboring countries to the east than with the long, rim-blown flutes. The details of the shape of some Turkish core gap flutes are reminiscent of the drawings of recorders in the Syntagma musicum by Michael Praetorius , published in 1619 . There are even more similarities between Turkish düdük types and recorders from the 18th century. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, boxwood from Turkey was exported to England under the name “Turkish box” for the construction of woodwind instruments, which makes it more likely that flutes would reach Turkey from there in the opposite direction.

A technical similarity between the edge-blown kaval and the ney is the polyphonic kaba playing style, which is unusual for a flute in art music . The music of the Mevlevi ritual dances still includes the flute sound rich in overtones, and since many ney players of the Mevlevi Order also performed in the Sultan's orchestra, they spread their style in secular chamber music throughout the Ottoman Empire. The kaval can optionally produce a "rough" ( kaba ) and "fine" ( ince ) sound and thus defies the usual classification, as is the case with the differently built and sounding Turkish double reed instruments zurna (loud, shrill) and mey (quiet, soft) ).

The kaval flute types are common among shepherds throughout Turkey, with the exception of a region in the northeast where shepherds play the bagpipe tulum . Despite the large number of regionally different sizes and shapes, there are some basic similarities in the style of play. The çoban kavalı and most other Turkish flutes have seven finger holes and one thumb hole. All Turkish rim-blown flutes and core gap flutes are played with the same fingering technique. With the index finger, middle finger and ring finger of the upper hand (optionally the right or left hand) the player grabs the first three holes and the other holes with all fingers of the lower hand. The finger holes are covered with the inside of the front phalanx. Fork grips are practically non-existent, the pitch and sound quality are instead influenced by semi-closed finger holes and by changing the blowing pressure. On the long flutes, the musicians predominantly use the partial tones of the first and second octaves, while on the short flutes they mostly use the normal register.

In many regions the players sing a deep drone (humming sound) of variable pitch in the flute on the long çoban kavalı to the melody, but not on short flutes and magnetic split flutes. In Central Asia, too, it is common to sing a humming sound in longitudinal flutes (for example with the tüidük ). The kaval is used almost exclusively as a solo instrument, otherwise alternating with a singing voice (the voice of the player). The musician Halil Bedii Yönetken (1899–1968) brought together an important collection of Anatolian folk songs between 1937 and 1954. For the social classification of kaval , Laurence Picken (1975) refers to Yönetken, who mentions that in Sivas he made the most beautiful recordings with kaval players in the prison there.

Occasionally in the 1960s the shepherd's flute played kaval together with the long-necked lute saz in folk music ensembles to accompany dance, similar to the way the çığırtma eagle-bone flute , which has now disappeared , was used in the coffee houses of Istanbul . These kaval ensembles were never a long shepherd's flute, but always a short rim-blown flute or a short core-gap flute without a sung drone part. Rural folk music ensembles rarely consisted of more than two types of instruments, only the urban fasıl orchestras, which emerged from the Ottoman court music of the 17th century, were an exception. For example, on the eastern Black Sea coast, the bagpipe tulum played at festivals in one village, the bowed lute Karadeniz kemençesi in another village and the kaval in another . It was not until the 1930s that larger ensembles were created for folk music, right through to new forms of folk music associated with pop music in the 1980s, such as etnik and özgün müzik .

literature

- Daniel Koglin: Lived game, played life. Improvisation and tradition in the music of the Greek kaval . (= Music Sociology. Volume 10) Bärenreiter, Kassel 2002, Chapter II: pp. 51–101, ISBN 3-7618-1359-7 .

- Laurence Picken : Folk Musical Instruments of Turkey. Oxford University Press, London 1975, pp. 381-471, ISBN 978-0-19-318102-1 .

Web links

- Anthony Tammer: Kaval and Dzamares: End-blown Flutes of Greece and Macedonia. UMBC, University System of Maryland

- Nedyalko Nedyalkov solo Kaval Gergiovski Melodies Bulgarian traditional music, solo kaval & gadulka. Youtube video

- Lyuben Dosev - Kaval Lessons. Youtube video

- Dilsiz Kaval. Youtube video (Turkish rim- blown dilsiz kaval )

- Hacı Ömer Elibol Dilsiz Kaval Dinletisi - Aybastı. YouTube video (played dilsiz kaval with circular breathing )

- Dilli çoban Kavalı çok dinlendirici bir ses verir Cengiz usta yaptı. Youtube video (Turkish flute dilli kaval )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Laura E. Gilliam, William Lichtenwanger: The Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection. Library of Congress, Washington 1961, p. 8 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Jean During: Gaval. In: Encyclopædia Iranica . 3rd February 2012.

- ^ Marek Stachowski: How to Combine Bark, Fibula, and Chasm (if one Speaks Proto-Turkic)? In: Studia Linguistica Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis. Volume 127, 2010, pp. 179-186, here p. 182.

- ↑ Marek Stachowski, 2010, p. 185.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, p. 382 f.

- ^ A b Romanian Traditional Instruments. Education and Culture, Lifelong learning programs, GRUNDTVIG.

- ^ Donna A. Buchanan: Performing Democracy: Bulgarian Music and Musicians in Transition. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2005, p. 101.

- ^ Daniel Koglin, 2002, p. 64.

- ^ Paul Collaer, Jürgen Elsner: Music history in pictures. Volume 1: Ethnic Music. Delivery 8: North Africa. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1983, p. 70.

- ↑ Kawala. Grinell College Musical Instrument Collection

- ↑ Hermann Moeck : Origin and tradition of the core-gap flute of European folklore and the origin of the music-historical core-gap flute types. (Dissertation) Georg-August-Universität zu Göttingen, 1951. Reprint: Moeck, Celle 1996, p. 42.

- ↑ Klaus P. Wachsmann : The primitive musical instruments. In: Anthony Baines (ed.): Musical instruments. The history of their development and forms. Prestel, Munich 1982, pp. 13–49, here p. 42.

- ^ Sibyl Marcuse : A Survey of Musical Instruments. Harper & Row, New York 1975, pp. 555, 557.

- ↑ Hermann Easter : Syrinx 1 . In: Wilhelm Heinrich Roscher (Hrsg.): Detailed lexicon of Greek and Roman mythology . Volume 4, Leipzig 1915, column 1642 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Bigamudre Chaitanya Deva: Musical Instruments. National Book Trust, New Delhi 1977, p. 61.

- ↑ Scheherazade Qassim Hassan, Jean During: Ney. In: Grove Music Online. 2001.

- ↑ Faizullah Karomatov, M. Zlobin: On the Regional Styles of Uzbek music. In: Asian Music. Volume 4, No. 1 ( Near East-Turkestan Issue. ) 1972, pp. 48-58, here p. 49.

- ↑ Hiromi Lorraine Sakata: The Complementary Opposition of Music and Religion in Afghanistan. In: The World of Music. Volume 28, No. 3 ( Islam ) 1986, pp. 33-41, here p. 35.

- ^ Subhi Anwar Rashid: Mesopotamia. (Werner Bachmann (Hrsg.): Music history in pictures. Volume II: Music of antiquity. Delivery 2) Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1984, p. 50.

- ↑ FM Karomatov, VA Meškeris, TS Vyzgo: Central Asia. (Werner Bachmann (Hrsg.): Music history in pictures. Volume II: Music of antiquity. Delivery 9) Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1987, pp. 26, 88, 154.

- ↑ Stephen Blum: Central Asia. 4. Instruments. In: Grove Music Online. 2001.

- ^ Heinz Zimmermann: Central Asia. In: Hans Oesch (Ed.): Extra-European Music (Part 1) (= New Handbook of Musicology. Volume 8) Laaber, Laaber 1984, p. 332.

- ^ Jean During, Razia Sultanova: Central Asia. A. Traditional art music and folk music. II. Kazakhs and Kyrgyz. 1. Kazakhs. B. Instruments. In: MGG Online, November 2016 ( Music in the past and present . 1998).

- ↑ Andreas Micheö, Oskár Elschek: instruments of folk music. In: Doris Stockmann (Ed.): Folk and popular music in Europe . ( New Handbook of Musicology , Volume 12) Laaber, Laaber 1992, p. 316.

- ^ Anca Florea: Wind and Percussion Instruments in Romanian Mural Painting . In: RIdIM / RCMI Newsletter. Volume 22, No. 1, Spring 1997, pp. 23-30, here p. 29.

- ↑ Yaroslav Mironenko: Moldova. II. Traditional music. 2. Pastoral music. (iv) musical instruments. In: Grove Music Online, 2001.

- ↑ Speranţa Rădulescu: Romania. III. Traditional musics. Instruments and pseudoinstruments (after Alexandru, 1956). A. Peasants and shepherds instruments. In: Grove Music Online, 2001.

- ↑ David Malvinni: The Gypsy Caravan: From Real to Imaginary Roma Gypsies in Western Music. Routledge, New York 2004, p. 57.

- ↑ Donna A. Buchanan: Bulgaria. II. Traditional music. In: Grove Music Online , May 28, 2015.

- ^ Stoian Petrov: Bulgarian Popular Instruments. In: Journal of the International Folk Music Council. Volume 12, 1960, p. 35.

- ↑ Donna A. Buchanan: Bulgaria. II. Traditional music. 2. Characteristics of pre-socialist musical culture, 1800-1944. (i) Gender, genre and labor. In: Grove Music Online, May 28, 2015.

- ^ Daniel Koglin, 2002, p. 65 f.

- ^ Daniel Koglin, 2002, p. 67.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, p. 382

- ↑ Lada Braschowanowa: Bulgaria. III. Folk music. 3. Folk musical instruments . In: MGG Online , November 2016 ( Music in the past and present , 1995).

- ↑ Vergilij Atanassov: The Bulgarian folk musical instruments. A system in words, images and sound. ( Ngoma. Studies on folk music and non-European art music. Volume 3, edited by Josef Kuckertz , Marius Schneider , Walter Salmen ) Musikverlag Emil Katzenbichler, Munich / Salzburg 1983, p. 136.

- ^ Daniel Koglin, 2002, p. 69 f.

- ^ Daniel Koglin, 2002, p. 61 f.

- ↑ Christo Vakarelski: Bulgarian folklore. De Gruyter, Berlin 1969, p. 376.

- ↑ Dimitrina Kaufman, Lozanka Peycheva: Traditional singing and music playing. In: Mila Santova, Dimitrina Kaufman, Albena Geogieva et al .: Living Human Treasures. Akademichno izdatelstvo, Sofia 2004, pp. 308–334, here pp. 312, 314.

- ^ Donna A. Buchanan, Metaphors of Power, Metaphors of Truth: The Politics of Music Professionalism in Bulgarian Folk Orchestras . In: Ethnomusicology, Vol. 39, No. 3, Fall 1995, pp. 381-416, here p. 387.

- ^ Carol Silverman: The Politics of Folklore in Bulgaria . In: Anthropological Quarterly. Volume 56, No. 2 ( Political Rituals and Symbolism in Socialist Eastern Europe ) April 1983, pp. 55-61, here p. 57.

- ↑ Timothy Rice: Bulgaria. In: Timothy Rice, James Porter, Chris Goertzen (Eds.): Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Vol. 8: Europe. Routledge, New York 2000, p. 893

- ^ Rudolf Maria Brandl : Greece. C. Folk music and dances. VI. Traditional regional styles. 2. Mainland. In: MGG Online, November 2016 ( Music in the past and present, 1995).

- ^ Daniel Koglin, 2002, p. 53.

- ^ Daniel Koglin, 2002, pp. 54f, 68.

- ^ Daniel Koglin, 2002, pp. 75f, 78.

- ↑ Daniel Koglin, 2002, pp. 64, 81–84

- ^ Daniel Koglin, 2002, p. 127f

- ↑ R. Conway Morris: Floyera. In: Laurence Libin (Ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Vol. 2, Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2014, p. 321.

- ^ Jim Samson: Music in the Balkans . Brill, Leiden / Boston 2013, p. 97.

- ^ Ines Weinrich: Macedonia. III. Folk music. 4. Instruments. In: MGG Online , November 2016 ( Music in the past and present , 1996).

- ^ Anthony Tammer: Kaval and Dzamares: 2. Making Kavals. UMBC, University System of Maryland.

- ↑ Anthony Tammer: Kaval and Dzamares: 3. Details of the Kaval. UMBC, University System of Maryland.

- ↑ Timothy Rice: The Surla and Tapan Tradition in Yugoslav Macedonia . In: The Galpin Society Journal. Volume 35, March 1982, pp. 122-137, here p. 122.

- ^ Carol Silverman: Music and Power: Gender and Performance among Roma (Gypsies) of Skopje, Macedonia . In: The World of Music. Volume 38, No. 1 ( Music of the Roma ) 1996, pp. 63-76, here p. 71.

- ↑ Branislav Rušić: The Mute Language in the Tradition and Oral Literature of the South Slavs . In: The Journal of American Folklore. Volume 69, No. 273 ( Slavic Folklore: A Symposium ) July – September 1956, pp. 299–309, here pp. 301 f.

- ↑ Jim Samson: Yugoslavia. 3. The Second Yogoslavia. In: Grove Music Online, January 13, 2015.

- ↑ The justification here is a renewal of the gaming tradition ("renew of playing the kaval"): Playing the kaval. Guardian of Serbian Identity. serbia.com.

- ↑ Birthe Trærup: Folk Music in Prizrenska Gora, Jugoslavia. A brief orientation and an analysis of the women's two-part singing. In: 14th Jugoslavian Folklore Congress in Prizren , 1967, p. 59.

- ↑ Roksanda Pejović: A Historical Survey of Musical Instruments as Portrayed in Mediaeval Art in Serbia and Macedonia. In: International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, Vol. 13, No. 2, December 1982, pp. 177–182, here Fig. 2b after p. 178.

- ↑ Jelena Jovanović: Identities Expressed through Practice of Kaval Playing and Building in Serbia in 1990s. In: Dejan Despić, Jelena Jovanović, Danka Lajić-Mihajlović (eds.): Musical Practices in the Balkans: Ethnomusicological Perspectives, Kgr.Ber. 2011 . (= Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Academic Conferences 142 ) Belgrad 2012, pp. 183–201, here after pagination of the PDF pp. 5, 8, 11.

- ↑ Jelena Jovanović: Rekindled Kaval in Serbia in 1990s and Kaval and Ney in Sufi Traditions in the Middle East: The Aspects of Music and Meanings. In: The Sixth International Symposium on Traditional Polyphony, Tbilisi State Conservatoire, Tiflis 2014, pp. 60–69, here pp. 62, 64.

- ^ Risto Pekka Pennanen: The God-Praising Drums of Sarajevo . In: Asian Music. Volume 25, No. 1/2 ( 25th Anniversary Double Issue ) 1993–1994, pp. 1–7, here p. 3.

- ^ Sibyl Marcuse : Musical Instruments: A Comprehensive Dictionary. A complete, authoritative encyclopedia of instruments throughout the world . Country Life Limited, London 1966, sv “Caval”, p. 83 f.

- ↑ Jelena Jovanović, 2012, pp. 14f, 18.

- ^ Zeljko Joksimovic - Lane Moje (Serbia & Montenegro) 2004 Eurovision Song Contest. Youtube video.

- ^ Marie-Agnes Dittrich: The self and the other in music theory and musicology . In: Michele Calella, Nikolaus Urbanek (ed.): Historical musicology: Fundamentals and perspectives. JB Metzler, Stuttgart 2013, pp. 307-317, here p. 308.

- ↑ Jane Sugarman, Zana Shuteriqi Prela: Albania. II. Traditional music. 1. Rural music. In: Grove Music Online, May 28, 2015.

- ↑ Mikaela Minga: Berat . In: Grove Music Online , May 28, 2015.

- ↑ Mikaela Minga: Shkodra . In: Grove Music Online , May 28, 2015.

- ↑ Bruno Reuer: Albania. II. Traditional music. 1. Instrumental music. In: MGG Online , November 2016 ( Music in the past and present, 1994).

- ↑ Ursula Reinhard: Turkey. III. Folk music. 5. Folk musical instruments. In: MGG Online , November 2016 ( Music in the past and present, 1998).

- ^ Henry George Farmer : Turkish Instruments of Music in the Seventeenth Century. As described in the Siyāḥat nāma of Ewliyā Chelebī . Civic Press, Glasgow 1937; Unmodified reprint: Longwood Press, Portland, Maine 1976, p. 18.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, p. 422.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, p. 415.

- ↑ Laurence Picken: Instrumental Polyphonic Folk Music in Asia Minor. In: Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, 80th Session, 1953-1954, London 1955, pp. 73-86, here p. 75.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, pp. 394-396.

- ^ Kurt and Ursula Reinhard: Music of Turkey. Volume 2: Folk Music. Heinrichshofen's Verlag, Wilhelmshaven, 1984, p. 129.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, p. 399 f.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, p. 412.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, pp. 412-414.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, pp. 418-420.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, p. 421 f.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, p. 439.

- ^ Kurt Reinhard : The music care of Turkish nomads . In: Zeitschrift für Ethnologie , Volume 100, Issue 1/2, 1975, pp. 115–124, here p. 120.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, pp. 443, 452.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, pp. 467-469

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, pp. 455 f.

- ^ Kurt and Ursula Reinhard: Music of Turkey. Volume 1: The Art Music. Heinrichshofen's Verlag, Wilhelmshaven, 1984, p. 80.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, pp. 457f, 573.

- ^ Daniel Koglin, 2002, p. 62 f.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, p. 460.

- ↑ Stephen Blum: Central Asia. 4. Instruments. In: Grove Music Online. 2001.

- ↑ Halil Bedii Yönetken. Turkish Music Portal.

- ↑ Laurence Picken, 1975, pp. 453-455.

- ^ Eliot Bates: Mixing for Parlak and Bowing for a Büyük Ses: The Aesthetics of Arranged Traditional Music in Turkey. In: Ethnomusicology. Volume 54, No. 1, Winter 2010, pp. 81-105, here p. 84.