Iranian music

Iranian music encompasses the art music tradition of Persian music in Iran , whose origins lie in the pre-Islamic, Sassanid period (early 3rd to mid-7th century) and which, after the subsequent conquest of the Iranian highlands by the Arab Abbasids, had a significant influence on the development of the Arabic music took. At the beginning of the 16th century, when the Safavids came to power , who elevated Shiite Islam to the state religion, Iranian musical culture fell into a phase of standstill and isolation, especially in relation to the culture of the Ottoman Empire, which was then dominant in the region . In the 18th century the older classical music fell into disrepair. Its current form, which includes the codification of the twelve dastgahs (modes) in the form of the radif , dates back to the 19th century.

The Iranian folk music traditions of the different ethnic groups, whose settlement areas extend beyond the national borders, are related to those of the neighboring countries. The numerous regional styles include Kurdish music in the north, the music of Balochistan in the south and the African-influenced music in the Persian Gulf .

In the middle of the 19th century, European music, western harmonics and notation were introduced - initially with military bands . Western classical and popular music was very popular in the 20th century until it was initially banned completely by the Islamic Revolution in 1979. After the gradual easing of the ban, there is now a lively pop and rock music scene in Iran.

history

- The position of musical performance in Iranian culture

The conflicting attitude towards music in the Iranian cultural area is based on a culture that arose from the conflict between ancient Persian customs and Islamic regulations. In ancient Persia, musicians were able to hold positions of high social standing. As Herodotus reports , music was widespread in Iranian territory as early as the Elamite and Achaemenid times . During the Parthian rule enjoyed z. B. the wandering singers great popularity. When the Sassanids were in power from 224 onwards, there were popular and highly respected musicians whose names have been passed down to the present day, and Iranian musical culture experienced its most important heyday. As under the Parthians, the musicians were mostly poets.

- Famous Sassanid Musicians (Pre-Islamic Period)

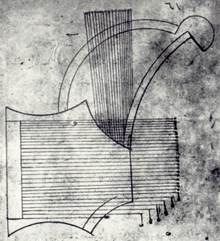

- Bārbad : Barbad the Great was a musician at the court of the Sassanids. He invented one of the oldest systems of music theory with seven royal and 30 derivative modes with 360 melodies ( dastan ), known as royal chosravani - dedicated to king Chosrou II. They correspond to the number of days in the week, month and year in Sassanian Calendar.

- Nakisā : Also court musician of the Sassanids and employees of Barbad.

- Sarkasch : The predecessor of the Barbad was an influential court musician.

- Ramtin

Among the most famous musicians, the master singers Barbad, Sarkad, Ramtin and Nakissa, there was fierce rivalry during the reign of Chosrou Parwiz (590–628). According to tradition, Barbad invented the lute and established the musical tradition of the Magham and possibly the Dastgah system. Since the Arab storm in the 7th century and the Islamization of the Iranian cultural area, Persian music gained influence in the Islamic world, starting primarily from al-Hīra , especially after the capital of the Abbasids, who ruled until 1258, was moved from Damascus to Baghdad. At the court of Hārūn ar-Raschīd there were numerous musical performances and the theoretical foundations of Persian-Arabic music were developed at this time. Since there was no musical notation in the current sense, musical transmission and training took place orally. Zirdjab, who fled to Spain in 821, is often cited as the artist with the greatest influence on Andalusian and Spanish music . Farabi and Avicenna were not only music theorists, but also masters of the lute alongside the ney. Five centuries after Barbad's death, Farabi collected pieces of music of his time and described the ancient notation in Persia. Around 2000 works and melodies were preserved that can still be played today.

- Abbasid musicians (8th - 13th centuries)

- Naschit Farsi

- Manṣūr ibn-Caʾfar Ḍārib Zalzal (died 791)

- Ibrahim Moussali (Ibrahim al-Mawsili)

- Ishaq al-Mawsili , son of Ibrahim M.

- Abu l-Hasan 'Ali Ibn Nafi' (called "Zirdschāb", German: "the nightingale"), disciple of Ishaq

- Abū l-Faraj al-Isfahānī (897–967)

The Iranian musical culture during the Mongolian rule from 1219 to 1381 was not very pronounced. During the following reign of the Timurids there was even a law that completely forbade making music under penalty of death. In spite of everything, important music-theoretical treatises emerged in the 13th and 14th centuries. Music has been viewed with suspicion since the Islamization of Iran. Even today, dances and thus the practice of music in general are still questioned by extremist sections, not only Shiite religious scholars, because they associate it with “fornication”. The Persian mystics ( Sufis ), on the other hand, understood music in connection with lyrical poetry as a means of transcendent experience and had a great influence on the traditional Persian art music that still exists today, also characterized by mystical-religious spirituality. The works of medieval Persian music theorists, mostly written in the Arabic scholarly language of the time, have had a great influence on the music of Near East and Central Asia up to the present day. The most famous personalities include:

- Abu Nasr Farabi (died 950)

- Avicenna (died 1037)

- Safi ad-Din al-Urmawi (died 1294)

- Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi (died 1311)

- Abd al-Qadir Maraghi (died 1435)

Another stagnation in musical developments occurred in particular with the establishment of Shiism as the state religion under the Safavids, who ruled until 1736, from 1501 onwards.

- Musician under the rulers of the Safavid dynasty (1501–1722 and 1729–1736)

- Ahamad Ghazwini

- Galalel Bachersi

- Mosafar Ghomi

- Hashem Ghaswini

- Mohammad Kamanchehi

- Mohammad Momen

- Shahsawar Charhar-tari

- Musicians of the Qajar era (creation of the Radif )

- Gholam-Hossein

- Ali-Akbar Farahani (1821-1857)

- Hossein-Gholi Farahani (1853-1916)

- Mirza Abdollah Farahani (1843-1918)

- Ali-Akbar Shahi (1857-1923)

- Nayeb Asdollag

- Gholam-Hossein Darwisch (1872–1926)

- Hossein Taherzadeh (1882–1955)

- Mirza Sattar, from around 1840 singer (from Ta'zieh ) from Ardebil and founder of new tonal modes

- Mina, Armenian orchestra leader from Isfahan at the Qajar court

- Zohre, Jewish orchestra leader from Shiraz at the Kajarenhof

The post-Soviet regime and the Taliban banned instrumental music and public performances in Afghanistan . In 2005 there were still voices like those of the Iranian President Mahmud Ahmadineschād who want to ban all kinds of Western music - contrary to the long Iranian music tradition.

Folk music

The Iranian cultural area is home to many different peoples such as the Bakhtiars , Baluch , Kurds and Azeri , each of whom developed their own stylistic peculiarities. Turkmen shaped the music in Khorasan in particular .

Kurdish music

The Kurdish music is known for its dance-oriented character.

Māzandarān

The northern province of Māzandarān produced various types of folk music such as instrumental and ritual music. Simple songs like Katoli , which are common in the area around the city of Aliabade Katol, are characterized by simple rhythms. Farmers sing this song when they drive a Catholic cow to pasture. Another way is called Leili's lover . Amiri songs dress the poems of Amir Pasvari, a poet of Masandaran, in melodies. Najma is popular throughout Iran ; Songs about the love of the Prince of Pars Province and a girl named Rana . Furthermore, the songs of the old merchants of Charvadar are part of the folk good of this area. Tscharvadari music stands out due to its rather untypical rhythm for Masandaran, which according to legend arose from singing while riding.

Afghan folk music

Afghan folk music consists on the one hand of women making music. This is banned in the homes because of the ostracism by the Koran. However, weddings or other celebrations are traditionally accompanied by music. The lively wedding parties are even the main source of income for professional musicians. The men are entertained by a male singer, whose lyrics are accompanied by instrumental music, as there is a separate sex party, while the women usually spend the night dancing and singing themselves. Jats, a wandering Roma people , also play their songs on instruments that are inviolable for non-Jats at weddings or other occasions. The lyrics of Afghan folk music typically tell of love and use the nightingale and the rose in their language symbolism. The story of Leili and Majnun , which is comparable to Romeo and Juliet , is also sung about . However, current items have no place in folk music. The Iranian New Year, Nouruz , is also celebrated in Afghanistan at the spring equinox . The musical part of the celebration is particularly important in Mazar-e Sharif . “The lion of instruments”, rubab , forerunner of the Indian sarod , is considered the national instrument of Afghanistan. This instrument with three melody strings, which Mohammad Omar , Isa Kassemi and Mohammed Rahim Chuschnawas master perfectly, made from the wood of the mulberry tree is an important part of Afghan folk music.

Tajik folk music

The Tajik music is heavily influenced by Uzbek and other Central Asian music. Folk music called falak is played at weddings and other celebrations in southern Tajikistan . Altogether one can distinguish variants of Tajik folk music from three areas:

- Pamir ( Berg-Badachschan )

- Central Kuhistoni (Gissar, Kulyab and Garm)

- Sogdiana (heavily influenced by Uzbek music)

Songs of all kinds, lyrical or instrumental music, are sung. The epic music surrounding the heroic story Gurugli is particularly important . Gharibi (songs of a stranger) are songs invented in the 20th century by poor farmers who had to leave their land. Gulgardoni or Boychechak are songs that are performed at spring festivals. Sajri Guli Lola music, for the celebration of the tulips , is accompanied by dance music and choirs. The most famous song of this holiday is called Naghschi Kalon . Other popular songs worth mentioning are Nat and Munodschot , which are sung when a boy is born. At weddings, Sosanda , mostly female musicians, play the members of a Dasta ensemble. Music from Badakhshan is known for the spiritual chants of lyric poetry called madah and accompanied by lute-like instruments. Well-known Tajik musicians are Barno Itshakova, Davlatmand Cholov, Daler Nasarow or Sino.

Traditional female chants

These occur in different forms within Persian folk music. In addition to the wedding songs already mentioned for Afghan music, these are mainly lullabies, funeral songs and workers' songs, such as those sung by carpet weavers and laundresses to make their work more pleasant. The Iranian singer and musician Maryam Akhondy , who lives in Cologne, has collected some of these songs from different musical cultures in Iran and published them on the CD Banu - Songs of Persian Women .

Classical Persian music

Since classical Persian music (موسيقى اصيل, musiqi-e assil ) originated from the traditional music of the Persian Empire and spread across all Persian-speaking countries, it is also adjective to Persian music (Persian also asil or, according to Western music-ethnological terminology, sonnati ("traditional music"), but not necessarily as Iranian Music ) called. In contrast to European classical music, Persian art music cannot be strictly demarcated from folk music (or from the “lighter” music of the earlier professional motrebi groups) by which it is influenced and which it influences. Traditional Classical Persian music that uses heterophonic elements , but does not have polyphonic counterpoint and chordal harmony like European music , but is characterized by clear differentiations between clearly played and less emphasized, softer tones that can also be found in other oriental musical traditions is, and until the 20th century was usually handed down from master to student without notation, has its origins in theخنياى باستانى ايرانى( Chonjâ-je Bâstâni Irâni ), traditional Persian melodies, from which, under Arabic and probably also Indian and Mongolian influences, the Persian maqam or dastgah system developed, which is the basis for artists making music with it, whereby the given elements ( of the Radif or the Dastgahs) oriented improvisation or interpretation is characteristic of the performance. In Persian music, a term that describes the emotional interaction or a mental-emotional state of the musician and the listener and thus helps to determine the success of a performance is Hāl . The repertoire of tones, rhythms and melodies can be found in the form of tahrir (cf. Arabic / Turkish Taksim ) outside of art music in sung or instrumental music. In contrast to the European, on a scale consisting of twelve (half) tones, Persian music has 22 (or 24) tones. Bārbad was the legendary singer of the Sassanid era .

Until the end of the 19th century, classical Persian music was largely settled at the court of the monarchs, especially under the Qajar ruler Nāser ad-Din Shah (1848 to 1896), whose love of music was known. But it was traditionally also cultivated at the meetings and ceremonies ( dhikr ) of the Iranian Sufi orders , as the poetry of the great classical Sufi poets was transported through it. Outstanding musicians who initiated a renaissance of the old Iranian musical tradition were Ali Akbar Farahani (1821–1857), the court musician Nāser ad-Din Shahs, and his son Mirza 'Abdollah (1843–1918), with whom the spread of Persian classical music in all Social classes began into it. Nur-Ali Borumand was an important music theorist and preserver of classical music in the 20th century.

The big cities, where the classical Persian music with each characteristic musical styles or schools is mainly played, are Tehran, Isfahan, Tabriz and Shiraz.

The first sound recordings of Persian music were made in Paris in 1905 with the musician Mirza Hoseyn Chan Bachtiyar. More recently, classical Persian music has spread among the people mainly through the introduction of cassettes from 1960 onwards. Before 1979 stars like the singer Gholam Hossein Banan and virtuosos on their instruments like Abol Hassan Saba , Ahmad Ebadi and Faramarz Payvar had their breakthrough. Well-known interpreters of traditional melodies and songs are still Farid Farjad (violinist), Javad Maaroufi (piano), Pari Zanganeh and Sima Bina (all singers).

The 1979 Islamic Revolution triggered a counter-movement and a return to classical Persian traditions , leading to a renaissance of Persian classical music, which led to national greats such as Parisa (singer), Parviz Meshkatian , Jamshid Andalibi , Kayhan Kalhor , Mohammad Reza Lotfi , Hossein Alizadeh , Shahram Nazeri , Sima Bina and Mohammad-Reza Shajarian were involved. The relationship between Islam and music has always been difficult. Many conservative religious scholars see even simple melodies and texts of the Persian classical period as problematic. Musicians like Parvaz Homay , who add critical texts with current references to classical Persian music, have to reckon with disabilities and performance bans. Women can only be musically active to a limited extent because they are only allowed to sing in front of an exclusively female audience. In order to be able to perform in front of a mixed auditorium, some of the singers regularly travel to concerts abroad or live and work, such as Maryam Akhondy, permanently outside their home country.

International representatives of Iranian music include Hossein Alizadeh and his pupil Sahba Motallebi (* 1977), who has performed with the Iranian National Orchestra and other ensembles around the world since 2000 .

The classical Afghan music is strongly characterized by Indian influences. Indian music instruments were also introduced in Afghanistan. Ghazal consists of Persian rhyming double verses, mainly from Bedil , Saʿdī and Hafez . A well-known interpreter of classic Afghan singing is Mohamed Hussein Sarahang .

Musical instruments

String instruments:

- Barbat

- Tar

- Dotar

- Rabab

- Santoor

- Shahrud

- Schurangiz

- Setar

- Tambireh

- Tanbur

- Tarab-angiz

- Chang

- Ghejchak

- Kamantsche

- Kanun

- Modified piano (see Pooyan Azadeh ) and electronic keyboard instruments

Wind instruments:

Percussion instruments:

Classic European music

Many radio stations from Tehran play concerts in their daily program and some Persian artists are known worldwide such as Shahrdad Rohani , the conductor of the LA Symphony Orchestra, or Lili Afschar , a classical guitar player and student of Andrés Segovia . The connection between European and Persian music is reflected in the folk anthem Ey Iran .

The Tehran Symphony Orchestra

The first European orchestra toured Persia in the days of Naser al-Din Shah . In 1856, two French musicians brought the first military band to Iran from the west. Two years later, Jean Baptiste Lumierre was appointed Kapellmeister. Lumierre's efforts to spread classical music culminated in the establishment of a music school. In 1869, 26 of the first graduates from this school founded the “Royal Zahi Orchestra”.

The orchestra's pioneers

These men from the very beginning included Gholamhossein Minbashian and Salar Moazez , who had studied with such famous teachers as Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Carl Flesch . After his return to Persia, Moazez founded the first private conservatory and in 1933 put together a 40-piece symphony orchestra with musicians from this school and the Tehran City Council together with Minbashian. This orchestra became the cornerstone of the Tehran Symphony Orchestra. With the help of ten Czech professional musicians who taught at the conservatory, the level could soon be raised. After these advances, World War II and its aftermath brought everything to a standstill. With the invasion of British and Soviet troops in the course of the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran , not only the Czech musicians left the country.

The foundation of the Tehran Symphony Orchestra

The idea of founding a real symphony orchestra also came from this time. In 1943 the “Tehran Symphony Orchestra” was created through the private initiative and enthusiasm of Parwiz Mahmud . After Mahmud was appointed director of the conservatory in 1946, he made a symphony orchestra from musicians from the conservatory's school orchestra.

The Anjoman-e Filarmonik-e Tehran (Philharmonic Society Tehran) was founded in November 1953, supported by a non-profit organization. All proceeds from concerts were used entirely to promote European classical music. The aim was to develop an audience interested in classical music through concerts, public performances, scientific lectures on music history and theory, building a music library and publishing a magazine. From 1963 the orchestra's activities were expanded with the support of Shahbanu Farah Pahlavi . She took over the patronage of the orchestra, so that from now on the orchestra was no longer only dependent on membership fees and income from concerts, but received generous financial support from Farah Pahlavi's office. The aim of this funding was to arouse interest in classical European music, especially among young people and students. The activities were a complete success: in 1970 the majority of the 1200 members of the orchestra's funding organization were students. For an annual fee of the equivalent of 3 euros (25 cents for students) you could become a member of the orchestra's funding organization and attend the orchestra's concerts.

Between 1963 and 1972, Heshmat Sanjari led the Tehran Symphony Orchestra to its first heyday. At that time the orchestra played with and under the leadership of internationally known musicians such as Yehudi Menuhin , Zubin Mehta , Isaac Stern and Herbert von Karajan , and the opera orchestra and symphony orchestra separated. The orchestra gave concerts not only in Tehran, but also in Abadan and Shiraz . In the later 1960s over 700 concerts with foreign and Iranian conductors were performed.

After the revolution

After the 1979 revolution, many art organizations were dissolved and the orchestras and music schools closed. The consequence of this was that many musicians emigrated. The symphony orchestra survived with ten musicians, who kept it alive through their own initiative with revolutionary hymns and occasional performances. Through their efforts, the foundation stone of the orchestra remained. From 1991 to 2005 Fereydun Naserin took over the direction of the orchestra. During this time Iranian conductors from abroad were repeatedly hired as guest conductors. On April 17 and 18, 2001, the Waidhofen / Ybbs Chamber Orchestra under the direction of Wolfgang Sobotka was the first western orchestra since the revolution to play works by Khohei, Beethoven , Johann Strauss (son) in the sold-out Vahdat Concert Hall (formerly the Rudaki Hall ). and Nader Mashayekhi. Since April 2006 the Tehran Symphony Orchestra has had a new permanent chief conductor in Nader Mashayekhi.

Nader Maschayekhi

The current conductor of the Tehran Symphony Orchestra, Nader Mashayekhi , was born in Iran in 1958 and grew up in a family of artists from Tehran. In 1978 he went to Vienna and studied composition with Roman Haubenstock-Ramati at the University of Music and Performing Arts . In addition, he took the subjects of conducting, composition and electroacoustic composition. In 1989 Mashayekhi founded the Ensemble Wien in 2001 (today Ensemble Wien 21st Century), whose programs, with their targeted mixture of historical, traditional and contemporary music, he played a key role. In 1992 he led computer music seminars in Hungary and in 1994 in Japan. In 1996 he was invited to Ottawa / Canada to give a lecture on “Multicultural Aspects in Contemporary Music”. Mashayekhi consistently continued the approaches of his teacher Roman Haubenstock-Ramati, which is particularly evident in the use of graphic forms of notation and variable forms. In his multi-media opera project Malakut (first performance 1997) he worked with visual and video artists; in recent years he has often included Persian painters, sculptors, writers and actors in his projects.

Persian pop music

Iranian or Persian pop music was developed in the 1970s with the introduction of new instruments such as the electric guitar. The most famous Persian singers of the time are Googoosh , Hayedeh and Vigen . This pop music was banned after the Iranian Revolution in 1979. Many of the musicians emigrated, especially to Los Angeles . Some well-known performers of Persian pop music are Dariush Eghbali , Hassan Sattar , Mahasti , Homeira , Andy Madadian , Faramarz Aslani , Moein , Mansour, Sandy, Ebi , Leyla Forouhar , Farschid Amin , Schahrsad Sepanlou , Afshin , Arash , Shadmehr Aghili , Kamran & Hooman , Shahram Solati , Shohreh Solati , Shahrokh etc.

Arrangements of Iranian pop music, even when traditional melodies are used, are often limited to (the western) major and minor keys (and also provided with corresponding harmonies).

Bandari is a branch of pop music that has its roots in southern Iranian folk music. The music, which is very danceable due to its special rhythm, is often played at weddings and other celebrations. The bagpipes are particularly characteristic .

Afghan pop music developed late in the 1950s, as after the destruction of the radio stations that had existed since 1925 in 1929, Radio Kabul was not broadcast nationwide until 1940. In the early days, Pashtun songs were broadcast with Dari texts . Films and especially music were first imported from Iran, Tajikistan and also Pakistan or India. Over time, however, there were also local artists. Parwin was the first Afghan woman to be played on the radio in 1951. Musicians like Ahmad Zahir - the Afghan Elvis Presley - or Biltun also became known. In 1977 Mahwasch , the most famous Afghan pop singer, sang the hit O Batsche . Since the “war on terror” reached Afghanistan and the Taliban overthrown, the Afghan music scene has re-emerged. Some groups like the Kabul Ensemble have been internationally recognized. Traditional Pashtun music from south-east Afghanistan also gained momentum.

Rock music

In the late 1990s, after a certain state liberalization of cultural policy, rock music and hard rock music flourished. Since then, new music groups have been emerging continuously. This development differs from Iranian pop music in that it tends to appeal to a younger fan base, those born after the revolution and, in contrast to exiled music from Los Angeles, largely originates in the Iranian underground. Meera and Barad were among the first rock bands in Iran . After the first bands appeared in secret, O-Hum , who offer Hafez ' poetry to rock' n 'roll sounds, were even allowed to give concerts for Christian Iranians in Tehran. Around the year 2000, the music label Hermes Records was founded in Tehran and released the first official rock albums by Iranian bands. The first international release was Kiosk's debut album .

Nowadays there are musical competitions and music criticism going underground. However, the Iranian government occasionally allows concerts under certain conditions. Bands like 127 and The Technicolor Dream have already played their English language pieces. In Iran, rock music with female vocal interludes or heavy metal is produced, as is death metal , e.g. B. the underground heroes ArthimotH and SdS from Isfahan or Arsames from Mashhad . The 1970s rock-influenced band Cheshme3 play punk rock .

In July 2005 the music company Bamahang Produktions in Canada released an album by the Iranian rock band Adame Mamuli for the first time , which is the first Iranian underground rock album to be downloaded from Apple's iTunes Music Store. The second album Aloodeh was released by O-Hum in December 2005 . The singer, guitar and setar player Mohsen Namjoo combines traditional Iranian music with rock and jazz . Most recently, Mazgani, who was born in Tehran and lives in Portugal, was considered the bearer of hope for Americana rock in Europe.

Electronic music

Electronic music has a special position in Iran. Since it is mostly composed without human singing, the pieces are not rejected in the same way as other music of Western origin. Many Iranian exiles are active in this area. The most famous band of this style is Deep Dish : Ali " Dubfire " Shirazi and Shahram Tayebi from Washington DC. Furthermore, DJ Behrouz , Behrous Nasai, from San Francisco, Fred Maslaki from Washington DC and Omid 16b , Omid Nourisadeh from London have achieved a certain level of awareness.

See also

literature

- Mehdi Assari: Howiyat-e musighi-ye melli-ye Iran wa Saz-ha. (The origin of Iranian music and its musical instruments), Tehran 2002.

- Arthur Emanuel Christensen : La vie musicale dans la civilization des Sassanides. In: Bull. De l'association francaise des amis de l'orient, 1936, no. 20/21

- Jean During : La musique iranienne - Tradition et évolution. Edition Recherche sur les Civilizations, Paris 1984

- Jean During, Zia Mirabdolbaghi, Dariush Safvat: The Art of Persian Music . Translated from French and Persian by Manuchehr Anvar. Mage Publishers, Washington DC 1991, ISBN 0-934211-22-1 (includes CD).

- Marie-Clément Huart: Musique Persane. In: Encyclopédie de la musique, première partie. vol. 5, ed. by Lavignac. Peris 1922, pp. 3065-3083.

- Nasser Kanani: Traditional Persian art music: history, musical instruments, structure, execution, characteristics. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Gardoon Verlag, Berlin 2012.

- Ruhollah Khaleqi: Sargozast-e Musiqi-ye Iran. ( History of Persian Music ) 2 volumes, Ferdowsi, Teheran 1954.

- Khatschi Khatschi: The Dastgah. Studies on New Persian Music. (= Cologne contributions to music research. XIX). Dissertation. Bosse-Verlag, Regensburg 1962.

- Josef Kuckertz , Mohammad-Taqi Massoudieh: Music in Būšehr, South Iran . (= NGOMA. Studies on folk music and non-European art music . Volume 2) 2 volumes. Katzbichler, Munich / Salzburg 1976, ISBN 3-87397-301-4 .

- Mohammad-Taqi Massoudieh: Avaz-e Shur. For the formation of melodies in Persian art music . (= Cologne contributions to music research. Volume 49). Bosse, Regensburg 1968.

- Lloyd Miller : Music and Song in Persia: The Art of Avaz. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City 1999.

- Eckhard Neubauer: Musician at the court of the earlier 'Abbasids. Dissertation. Johann Wolfgang Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main 1965.

- Ella Zonis: Classical Persian Music. Harvard University Press, Cambridge / Massachusetts 1973.

Web links

- Iranian Music. Iran Chamber Society

- Traditional Persian musical instruments. Irania.eu

- Peyman Nasehpour: Rhythmic Forms of Persian Art Music. Rhythmweb

- Persian Musicians Index. (PDF; 4.68 MB) inthegapbetween.free.fr

- The Progressive State of Iran, in Music. Reviews of Iranian progressive music.

- Persian Music. IranSong

Remarks

- ↑ Mary Boyce : The Parthian Gōsān and Iranian Ministrel. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (JRAS, New Volume), April 1957, pp. 10-45, pp. 17-32.

- ^ Nasser Kanani: Traditional Persian Art Music: History, Musical Instruments, Structure, Execution, Characteristics. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Gardoon Verlag, Berlin 2012, pp. 51–76.

- ↑ Alec Robertson, Denis Stevens: History of Music. (German by E. Maschata), I-III, Manfred Pawlak Verlagsgesellschaft, Herrsching 1990, ISBN 3-88199-711-3 , pp. 148-153.

- ^ Henry George Farmer : The Music of Islam. In: Ancient and Oriental Music. Edited by E. Wellesz, Oxford University Press, London 1957, p. 427.

- ^ Nasser Kanani: Traditional Persian Art Music: History, Musical Instruments, Structure, Execution, Characteristics. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Gardoon Verlag, Berlin 2012, pp. 76–83.

- ^ Nasser Kanani: Traditional Persian Art Music: History, Musical Instruments, Structure, Execution, Characteristics. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Gardoon Verlag, Berlin 2012, pp. 83–118.

- ^ Nasser Kanani: Traditional Persian Art Music: History, Musical Instruments, Structure, Execution, Characteristics. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Gardoon Verlag, Berlin 2012, pp. 87–93.

- ↑ Mehdi Barkeschli: Andische-haye Elmi-e Farabi dar bare Musighi. (Farabi's scientific reflections on music), Tehran 1978.

- ↑ Mahmoud El Hefny: Ibn Sina's music theory, mainly explained in his Naǧāt - together with the translation and publication of the music section of the "Nağāt. Philosophical Dissertation, Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin, 1931.

- ^ Bertold Spuler : The Mongols in Iran. Politics, administration and culture of the Ilchan period 1220–1350. Habilitation thesis, Hinrichs, Leipzig 1939; 4th expanded edition. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1985, pp. 323, 354 and 366

- ^ Nasser Kanani: Traditional Persian Art Music: History, Musical Instruments, Structure, Execution, Characteristics. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Gardoon Verlag, Berlin 2012, pp. 105–118.

- ^ Eckhardt Neubauer: Music during the Mongol period in Iran and the neighboring countries. In: Islam. Volume 45, No. 3, 1975, pp. 233-259.

- ↑ The traditional Arabic term for "music" isطرب, DMG ṭarab 'joy, delight, music', cf. H. Wehr: Arabic dictionary for contemporary written language , Wiesbaden 1968, p. 503.

- ^ Dariush Safvat: Musique Iranienne et Mystique. Translated and annotated by Jean During. In: Etudes Traditional. No. 483, 1984, pp. 42-54, and No. 484, 1984, pp. 94-109.

- ↑ See also Seyyed Hoseyn Nasr: The Influence of Sufism in Traditional Persian Music. In: Studies of Comparative Religions. Volume 6, No. 4, 1972, pp. 225-234.

- ^ Nasser Kanani: Traditional Persian Art Music: History, Musical Instruments, Structure, Execution, Characteristics. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Gardoon Verlag, Berlin 2012, pp. 237–246.

- ^ Nasser Kanani: Traditional Persian Art Music: History, Musical Instruments, Structure, Execution, Characteristics. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Gardoon Verlag, Berlin 2012, pp. 96–99.

- ^ Nasser Kanani: Traditional Persian Art Music: History, Musical Instruments, Structure, Execution, Characteristics. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Gardoon Verlag, Berlin 2012, pp. 99-104.

- ^ Nasser Kanani: Traditional Persian Art Music: History, Musical Instruments, Structure, Execution, Characteristics. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Gardoon Verlag, Berlin 2012, p. 118 f.

- ^ During et al. (1991), p. 42.

- ↑ This is a problematic term because Iranian art music, as largely improvised music, is more exposed to age-dependent influences than the regional forms of music, which are actually to be assessed as "traditional" or "ancestral", which are part of a chain of musical forms that are from the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia to Northwest Africa and the Balkans.

- ↑ Lotfollāh Mofakhham Pāyān: Dastgāhā-ye Musiqi-e Sonnati-e Iran (Compilations d'après les Radifs Āqā Mirzā Abdollāh, Āqā Mirz Hoseyn Qoli et Darvish Khān). Académie des Lettres et Arts, Tehran 1977.

- ↑ During, Mirabdolbaghi (1991), p. 19

- ^ Bruno Nettl : The Radif of Persian Music. Studies of Structure and Cultural Context in the Classical Music of Iran. Elephant & Cat, Champaign / Illinois 1987, 2nd edition. 1992, p. 160.

- ↑ Jean During, Zia Mirabdolbaghi (1991) 170th

- ↑ Nasser Kanani: The Persian Art Music. History, instruments, structure, execution, characteristics (Mussighi'e assil'e irani). Friends of Iranian Art and Traditional Music, Berlin 1978, p. 5 f.

- ^ During et al. (1991), p. 50 f. ( Somā 'Hozur ).

- ↑ During, Mirabdolbaghi (1991), p. 15

- ↑ Edith Gerson-Kiwi: The Persian Doctrine of Dastga Composition. A phenomenological study in the musical modes. Israel Music Institute, Tel-Aviv 1963, p. 8.

- ↑ Edith Gerson-Kiwi: The Persian Doctrine of Dastga Composition. A phenomenological study in the musical modes. Israel Music Institute, Tel-Aviv 1963, pp. 8-16.

- ^ Nasser Kanani: Traditional Persian Art Music: History, Musical Instruments, Structure, Execution, Characteristics. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Gardoon Verlag, Berlin 2012, pp. 246–249.

- ↑ During, Mirabdolbaghi (1991), p. 15 f. and 92-97.

- ↑ Jean During, Zia Mirabdolbaghi (1991) 170 f. and 241 f.

- ↑ Encyclopaedie Iranica Hal .

- ↑ During, Mirabdolbaghi (1991), p. 50

- ^ Hormoz Farhat: The Dastgāh Concept in Persian Music. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1990, ISBN 0-521-30542-X , pp. 7-18 ( Intervals and scales in contemporary Persian music ).

- ↑ Another term for Persian classical music, Persian آواز, DMG Āwāz , means both “song” and “voice” as well as “ maqām ” (mode).

- ^ Nasser Kanani: Traditional Persian Art Music: History, Musical Instruments, Structure, Execution, Characteristics. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Gardoon Verlag, Berlin 2012, pp. 118–145.

- ↑ During, Mirabdolbaghi (1991), p. 15

- ^ During et al. (1991), p. 43.

- ↑ Sahba Motallebi: Niayesh. Ketab Corp., Los Angeles 2005, ISBN 1-59584-061-3 , publisher information .

- ↑ Publication by Her Highness Office (Farah Pahlavi), 1354 1975, p. 41ff.

- ↑ See for example Abbas Barari (Peyman): Forty years of Pop. Compiled and rearranged. Volume 1-3. Roham, Teheran 2002, ISBN 964-5696-26-7 or 964-6596-22-4.

- ↑ See for example Ali Mghiseh: The best Persian music. 1993.