Romeo and Juliet

Romeo and Juliet ( Early Modern English The Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet ) is a tragedy by William Shakespeare . The work tells the story of two young lovers who belong to warring families and who, under unfortunate circumstances, die by suicide. The plot of the play spans a period of five days and takes place in the northern Italian city of Verona in summer . The work was probably created in the years 1594–96. It first appeared in print in 1597. Shakespeare's main source was Arthur Brooke's The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Iuliet from 1562. Romeo and Juliet are considered the most famous lovers in world literature. The material has been processed musically and literarily in many variations, there have been numerous film adaptations, and the work has enjoyed unbroken popularity on stage since its creation.

Overview

Summary

The tragedy takes place in the Italian city of Verona and is about the love of Romeo and Juliet, who belong to two warring families, the Montagues (Romeo) and the Capulets (Juliet). The feud goes so far that those involved regularly let themselves be carried away to insults and bloody fencing matches as soon as they meet in town. That is why Romeo and Juliet keep their love affair hidden from their parents. Without their knowledge, they let their brother Lorenzo marry, who secretly hopes to be able to contribute a first step towards the reconciliation of the warring families. Nevertheless, there is a fight between Romeo and Tybalt, a Capulet and Juliet's cousin, in the course of which Tybalt is killed by Romeo. Romeo is banished from Verona and has to flee to Mantua . Julia, who, according to her parents' wishes, is to be quickly married to a certain Paris, asks Brother Lorenzo again for help. This persuades her to take a sleeping potion that will put her in a death-like state for several hours in order to escape the wedding. Romeo is to be informed of this plan by a letter, which however does not reach him due to an accident. In the meantime, a friend of Romeo sees Juliet, who has now been buried, in her family crypt, rushes to Romeo and tells him about the alleged death of his lover. Romeo rushes to Verona to his wife's grave to see her one last time, then he takes poison and dies by her side. At the same moment, Juliet wakes up from her death-like sleep, sees what has happened, takes Romeo's dagger and kills herself out of desperation. When the hostile parents learn of the tragic love affair, they recognize their complicity and are reconciled over the grave of their children.

main characters

The stage company of the work consists of a total of 32 people and a choir. The members of two warring families are at the center of the plot. In addition to Julia and her parents, the Capulet family includes Julia's wet nurse, her suitor Paris and her cousin Tybalt. The Montagues family includes Romeo and his parents, Romeo's cousin Benvolio, his mentor brother Lorenzo and his friend Mercutio. Overall, the structure of the groups of figures is very symmetrical.

Told the time and places of the action

The action takes about a week. The work is set in the northern Italian cities of Verona and Mantua in the 14th century.

content

Act I.

The drama begins with a prologue in the form of a sonnet , in which the audience is informed that the star-crossed lovers , Romeo and Juliet, belong to warring families, die and through their death reconcile their warring families become.

[Scene 1] The servants of the feuding houses of Capulet and Montague begin a quarrel in a public square in Verona. Benvolio, Montague's nephew, wants to prevent a fight, but Tybalt, Capulet's nephew, calls on him to fight too. A large crowd is quickly involved; Partisans rush in, including the heads of the two families. The Prince of Verona is furious with the public struggle and imposes the death penalty for future such incidents. Romeo was not present at this fight, and his parents ask Benvolio about him. You learn that he is unhappily in love with the cool Rosalinde and that he wanders lonely through the landscape. When Romeo himself appears, Benvolio tries to help him out of his melancholy, but Romeo fends off all attempts of his friend with witty puns about his lovesickness. [Scene 2] Verona, one street: Count Paris asks Capulet for Juliet's hand. Capulet is happy about this, but has concerns that Julia, who is not yet fourteen, is currently too young to marry. That is why he invites the suitor to a big dance festival that evening, at which he should begin to win Julia's favor. A servant is given a guest list and is supposed to distribute invitations in Verona. The servant, who does not know how to read, asks the approaching Romeo and Benvolio if they could read him the names. Rosalinde will also be at the ball, so Benvolio persuades Romeo to go masked with him to the festival of the Capulets and to compare his beloved with other girls present. [Scene 3] The following scene takes place in Verona, in Capulet's house. Countess Capulet has Julia's wet nurse, a very talkative person, bring her daughter to her home. She tells Julia that Count Paris has asked for her and that she will get to know him at the evening party. The nurse is enthusiastic, Julia on the other hand very reserved, but agrees that she will look at the suitor. [Scene 4] Verona, in front of Capulet's house: Romeo and his friends Benvolio and Mercutio have masked themselves and are ready to go to the festival of the Capulets. The friends want to tear Romeo out of his love melancholy with slippery puns. Especially Mercutio excels with a long fantastic speech about Queen Mab, the midwife of the elves. But Romeo cannot tear any of this out of his gloomy mood: he claims to have a premonition of his impending death. [Scene 5] Verona, a hall in Capulet's house: Capulet warmly welcomes all his guests, whether invited or not. Romeo sees Juliet and falls in love with her at first sight. He is convinced that he has never seen such beauty before. Despite the mask, Tybalt recognizes Romeo by his voice and wants to fight him immediately. But Capulet rebukes his aggressive nephew and explains that Romeo enjoys his hospitality and is a man of honor. In the meantime, Romeo has approached Juliet, who for her part is enchanted. Both hands are found, then also their lips. As if by itself, the verses of the lovers form into a common sonnet . Romeo has to go, not without first finding out that Juliet is the daughter of his enemy. Julia also learns to her dismay that she has lost her heart to a man from the opposing family.

Act II

Prologue: Again in a sonnet the audience is shown the situation of the lovers once again: Both are in love with a mortal enemy. At the same time, the poem suggests that the passion of the two will find ways to realize their love in spite of the unfavorable circumstances.

[Scene 1] Verona, a street near Capulet's garden: Romeo, drawn to Juliet, hides in the garden from his friends, who are looking for him in vain. Mercutio, in his mocking manner, conjures up lovesick Romeo as if he were a confused ghost, and makes offensive remarks about it. When Romeo does not show himself, Benvolio and Mercutio go home without him. [Scene 2] Verona, Capulet's garden. In the so-called balcony scene, Julia appears at the window. Romeo hears her speaking of her love for him, steps forward and in turn confesses his love for her too. Juliet is frightened, but also happy, and Romeo repeatedly assures him how serious he is about her. The lovers agree to be married the next day, Juliet's wet nurse should let Romeo know. [Scene 3] Brother Lorenzo is at work in his cell, he cultivates the monks' garden and already reveals excellent knowledge of medicinal plants. Romeo comes and asks Lorenzo to secretly marry Juliet. Lorenzo initially criticizes Romeo because he forgot Rosalinde so quickly, which aroused his doubts about the new enthusiasm. Nevertheless, he agrees, in the hope that this marriage will finally end the unfortunate dispute between the families. [Scene 4] Verona, a street: Mercutio and Benvolio wonder where Romeo is, because Tybalt has challenged her friend to a duel. In a passionately pointed speech, Mercutio shows his contempt for the dueling fanatic Tybalt, who in his opinion is affected. Enter Romeo The friends indulge in suggestive puns for a while until Juliet's wet nurse appears, who first has to endure Mercutio's jokes before Romeo tells her that the wedding will take place an hour later in Brother Lorenzo's cell. [Scene 5] Verona, Capulet's garden: Juliet is waiting impatiently for the nurse. After her arrival, she lets the young girl fidget a little before telling her when and where the secret wedding is to take place. [Scene 6] Verona, brother of Lorenzo's cell: Lorenzo wed Romeo and Juliet. He is now completely convinced that he can end the years of conflict between the warring families in this way. Nevertheless, he once again urges his protégé Romeo to exercise moderation.

Act III

[Scene 1] Verona, a public square: Benvolio asks Mercutio to go home with him, because it is a hot day and the supporters of the Capulets are looking for an argument. Mercutio jokingly accuses Benvolio of being a belligerent character himself and makes no move to leave the square. Tybalt comes up and asks about Romeo. This appears and is challenged by Tybalt to a duel, which Romeo refuses, because he knows that he is now related to Tybalt. Instead, he wants to make peace. Mercutio interferes and begins a fencing match with Tybalt. Romeo simply walks between them, at which point Tybalt insidiously inflicts a fatal wound on Mercutio. Mercutio curses the warring houses and dies. Romeo, beside himself with pain and anger, draws his sword and stabs Tybalt. He realizes what he's done and flees. The people come running, including the heads of families. Benvolio reports the course of the battle to the Prince of Verona. Countess Capulet demands that Romeo be killed, but the prince punishes him with banishment because Tybalt had provoked the act. [Scene 2] Verona, Capulet's house: Julia impatiently awaits the wet nurse's arrival again. She appears and complains, so that Juliet must first assume that Romeo is dead. When she learns that Romeo killed Tybalt, she is initially horrified, but quickly realizes that Tybalt must have been the provocateur. Since Romeo is banished, Juliet believes that she will never see her wedding night, but the nurse offers to go to Romeo and bring him to her for that night. [Scene 3] Verona, brother Lorenzo's cell: Romeo is hiding with Lorenzo; he learns of his exile and can only see in it a worse punishment than death, because exile means separation from Julia. The nurse appears, but that doesn't bring Romeo to his senses either. He even wants to kill himself because he is afraid that Julia will no longer be able to love him, Tybalt's murderer. Lorenzo takes the dagger away from him and draws up a plan: Romeo should visit Juliet again that night, but then hurry to Mantua. Romeo is convinced that there is still hope. [Scene 4] Verona, Capulet's house: Paris again submits its proposal to Capulet. Initially defensive, he then surprisingly unauthorized set the wedding for Thursday - three days later. Countess Capulet is to inform Julia. [Scene 5] Verona, Capulet's garden: After their wedding night, Romeo and Juliet have to part because the lark is singing, a sign of the dawning. Juliet says it's the nightingale to keep Romeo to himself a little longer; but when he agrees to stay and also want to die, she agrees to leave. Countess Capulet visits Julia to inform her of the father's decision. Julia is horrified and refuses. Capulet arrives and silences them with crude words and the threat of disinheriting them: their will does not count here. When the parents left, the nurse Julia also advised her to marry Paris. Desperate, Julia decides to ask Lorenzo for advice.

Act IV

[Scene 1] Paris asks the surprised Lorenzo to wed him to Julia on Thursday. Julia appears, speaks evasively with Paris until Paris leaves full of hope. Julia desperately asks Lorenzo for advice; if he doesn't find one, she'll kill herself and pulls a knife. Lorenzo sees a solution: he gives Julia a sleeping potion that will put her in a seemingly dead state for 42 hours. Her parents will bury her. In the meantime, Romeo will be informed by Lorenzo's brother Markus and will free her from the family crypt of the Capulets. Julia agrees. [Scene 2] Verona, Capulet's house: Capulet is already inviting guests to Juliet's wedding. Julia appears and pretends to consent to the marriage. The happy Capulet then surprisingly announces that the wedding should take place on Wednesday, so moves it one day ahead. [Scene 3] Verona, Juliet's room: Juliet experiences fear and doubt: Does the monk want to get her out of the way? Won't waking up in the crypt go mad? Tybalt's bloody spirit appears in a terrifying vision. But her love is ultimately stronger and she drinks Lorenzo's remedy. [Scene 4] Verona, Capulet's house: The wedding is being prepared in Capulet's house. Capulet is excited and interferes; the nurse wants to send him to bed. But morning has already broken, so Capulet sends the nurse to wake Julia up. [Scene 5] Verona, Capulet's house: the nurse finds the seemingly dead Julia. Capulet, his wife and Paris join them; all are horrified and lament their cruel fate. Lorenzo is fetched and asks the mourners to keep their composure and transfer Julia to the family vault.

Act V

[Scene 1] Mantua, a street: Romeo interprets a dream in which he sees himself dead and is brought back to life by Juliet as a good sign. He expects news from Lorenzo, instead his servant Balthasar appears, who tells him about Juliet's death. Romeo spontaneously decides to defy fate and to reunite with Juliet in death. He buys poison from a pharmacist and makes his way to the tomb of the Capulets. [Scene 2] Verona, brother Lorenzo's cell: Lorenzo learns that his brother Markus could not deliver the letter to Romeo because a plague that suddenly broke out prevented this. Lorenzo rushes to the crypt to bring Julia, who will soon wake up, to his cell. [Scene 3] Verona, a cemetery: Paris brings flowers to the cemetery to scatter them in front of the crypt for Juliet. When his servant hears someone coming, they both hide and watch Romeo begin to break into the tomb. Paris confronts Romeo, who asks him to leave, otherwise he will have to kill him. Paris does not give way, they draw their swords and fight, Paris dies. Romeo fulfills his last wish to be allowed to lie in the crypt next to Juliet. He looks at the sleeping Julia one last time and then takes the deadly poison. Lorenzo arrives when Juliet wakes up and sees the dead Romeo. However, he flees from the approaching guards. Juliet kisses Romeo's lips and stabs himself with his dagger. Guards and people rush over. Montague reports that his wife died of grief over Romeo's exile. Lorenzo describes what happened to the Prince of Verona and the remaining heads of the families. The old adversaries reconcile, shaken and decide to erect a monument in pure gold for the two lovers. The prince speaks the closing words:

- "For never was a story of more woe / Than this of Juliet and her Romeo."

- "Because never was there such a bitter lot / as Julias and her Romeos."

Literary templates and cultural references

The motif of lovers separated by adverse circumstances is deeply rooted in mythology and fairy tales . Examples or correspondences for such couples can be found in the legends of Hero and Leander , Pyramus and Thisbe , Tristan and Isolde , Flore and Blanscheflur and Troilus and Cressida . In the novella literature of the Renaissance, the basic features of the story are already presented in the Novellino by Masuccio of Salerno (approx. 1474–1476); through new proper names and additional plot elements such as the balcony scene or the double suicide at the end, L. da Porto gave it its familiar shape around 1535. The fate of Troilus and Cressida was already portrayed by Geoffrey Chaucer in his epic Troilus and Criseyde . This work strongly influenced Shakespeare's immediate model, Arthur Brooke's epic The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet from 1562. Both Brooke and his compatriot William Painter with Rhomeo and Julietta from 1567 used the French version by Pierre Boaistuau (1559), which in turn was based on Matteo Bandello's Romeo e Giulietta (1554) and Luigi da Porto's Giuletta e Romeo (around 1530) fall back. The best-known version of Bandello among these versions already has essentially the same plot and the same ensemble of characters as Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet .

Shakespeare worked as the main source with Brooke's 3,000-line epic poem, which can already be seen in a series of almost literal adoptions. It is unclear whether he also used Painter's work, but it is likely. So he probably took the name Romeo from Painter instead of Brooke's Romeus . In essence, Shakespeare leaves the outline of the story as Brooke presents it, with the dual themes (family feud and love story) of Shakespeare - in contrast to Brooke - being mentioned right at the beginning of the drama and thus determining the course of the tragedy. With Brooke the story unfolds over a time frame of nine months, with Shakespeare it is streamlined to a few days. The roles of Tybalt and Paris, on the other hand, are expanded and deepened by Shakespeare. In addition, Shakespeare packs all the important moments of the plot into a sequence of scenes that create exciting and dramatically effective processes. The time compression in Shakespeare's tragedy also reinforces and intensifies the causal relationship between the individual events. While Brooke's secret marriage lasts two months before the fight with the Capulets and the killing of Tybalt, the two lovers in Shakespeare's work only spend one night together, during which they already know about Tybalt's death and Romeo's exile.

In the preface to Brooke's poem, the strictly exemplary character of the story is emphasized; the tragic ending is portrayed as Heaven's punishment for unbridled passion and disobedience to parents and counselors. Shakespeare, on the other hand, eliminates Brooke's moralizing narrative comments and shifts all reflections into the awareness of the dramatic characters with their limited perspective. In this way, in Shakespeare's play, fate turns into an inexplicable and unpredictable force; In its unconditional nature, love destroys itself in the inevitable conflict with the environment. In the tight lapse of time of four days and nights in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet , numerous chainings and ironic contrasts of situations arise, which condense the impression of tragic inexorability. In contrast to Brooke's original, Shakespeare's Julia is also almost a child; this brings the purity of her love and her maturation into a tragic heroine to the fore. The lyrical richness of the language that Shakespeare uses for his portrayal of the love affair between Romeo and Juliet has no counterparts in his models.

With the additional expansion of the secondary characters, Shakespeare continues to create interlocutors and accompanying or contrasting characters for his main characters in order to be able to use the comedy-like and playful potential of the story in a more dramatic way. The colorful comedic counter-world to the emotional rapture of the lovers, created primarily through the character of Mercutio, is just as much Shakespeare's own work as the role of arbiter of Prince Escalus and the role of the “spiritual father” Lawrence, which, in contrast to the models, give his drama significant political and moral contours to lend.

The warring families of the Capulets and the Montagues, however, are not an invention of Shakespeare. They are already more than three hundred years earlier acquired work Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri as "Montecchi e Cappelletti" as an example of feuding families.

Dating

The exact time of origin of the drama has not been passed down and has led to different hypotheses and assumptions in research with regard to historical references in the text or intertextual comparisons as a basis for dating. The period of origin can, however, be narrowed down to the years between 1591 and 1596 based on various indications.

The piece cannot have been written later than 1597 ( terminus ante quem ), since the first unauthorized four- o-tho edition of the piece was published that year under the title An Excellent Conceited Tragedie of Romeo and Juliet , although the author was not named . The title page of this first publication notes numerous previous public performances of the play ( "As it has been often (with great applause) plaid publiquely" ) by the drama group of the right Honorable the L [ord] of Hunsdon his Seruants , how the Shakespeare troupe changed between July 1596 and March 1597. The first historically documented performance of the piece also took place in 1597.

Further external evidence - such as a no longer breaking series of quotations from the play in other plays from 1598 - suggest a rather earlier date of creation. Romeo and Juliet is also explicitly listed in Francis Meres' catalog of the works of Shakespeare Palladis Tamia published in 1598 , which research sees as confirmation of Shakespeare's authorship, but does not clarify the question of the exact date of the work's creation. The stylistic proximity to Nashes' pamphlet dialogue Have With You To Saffron-Walden (1595) leads various scholars to believe that Romeo and Juliet was written around 1596.

Another part of Shakespeare researchers assume an earlier date of origin. Based on the wet nurse's reference in scene 1.3 (line 23) to an earthquake exactly 11 years ago and verifiable soil erosion in England in 1580, the tragedy is dated to 1591. In support of such an early dating, the argument is put forward that the compilers or printers of the bad quartos Q1 must have been aware of other dramas by Shakespeare that were written around 1590/91, in particular the bad quartos by Henry VI , parts 2 and 3 (around 1590/91). Despite existing parallels, however, it cannot be proven with certainty whether the creators of the first quarto print of Romeo and Juliet actually had access to these other dramas; the recourse could just as well have been made in another direction.

In addition, obvious borrowings in Romeo and Juliet from Samuel Daniel's Complaint of Rosamund (1592/94) and parallels to various poems by Du Bartas published in John Eliot's Ortho-epia Gallica in 1593 give reason to believe that Romeo and Juliet can hardly have been made before 1593. For this period, too, earth displacements can be determined in individual regions of England, for example in Dorset and Kent, which could be related to the statement by the wet nurse in scene 1.3. Against the background of these circumstantial evidence or evidence, numerous Shakespeare researchers today tend to date the creation of the work to the period between 1594 and 1596. A limitation of the dating to these years can also be made through a linguistic and stylistic proximity to other Shakespeare works that were written around this time, further substantiate, but without any unequivocal evidence can be provided.

Text history

As with all other Shakespeare works, a manuscript has not survived. Text transmission raises a number of complicated questions that make the publication of Romeo and Juliet particularly difficult. The piece was very popular from the start and was published in four separate editions in quarto format (Q1 to Q4) before being printed in the first folio edition (F) in 1623.

Essentially, two text sources form the basis for newer text editions. On the one hand is the first Quarto issue of the printer and publisher John Danter of 1597, which generally considered the modern publisher as so-called bad quarto edition is considered, taken as a textual basis. This early print edition was probably reconstructed from the memory of actors as a pirated print and shows significant abbreviations, gross deviations, metrical errors, repetitions and the like. On the other hand, the second quarto edition, which was published with numerous changes and extensions under the title The Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet in 1599, is also used as a text source as a so-called good edition. The title page of Q2 already contains the information that this text edition is a revised, expanded and corrected version of the tragedy: “ Newly corrected, augmented and amended: As it hath bene sundry times publiquely acted, by the right Honorable the Lord Chamberlaine his Seruants . " This version, printed under the responsibility of Thomas Crede, goes back to the same stage version as Q1, but is almost certainly based on a written record, probably a rough version ( foul paper ) of Shakespeare's handwritten manuscript. The second, longer quarto edition offers a comparatively reliable text, but also contains a number of dubious passages. The handwritten submission of Q2, which was in some cases difficult to read, led to various correction attempts and text changes before going to press; likewise, the printing of Q2 was not completely unaffected by the previous print edition Q1. Most of the more recent Shakespeare editors therefore do not assign any text authority independent of Q1 to individual passages of the second four-high print.

At the same time, conclusions can be drawn with a relatively high degree of certainty about a performance of the work during Shakespeare's lifetime from the detailed scene instructions in the first print of Q1. The omissions and abbreviations as well as the rearrangements of text passages in the Q1 edition are therefore not only due to gaps in memory during the reconstruction of the text, but could also be due to the performance practice at the time, for example to avoid all roles even without a sufficient number of actors in the To be able to cast a theater troupe or to limit the playing time.

The following four-high editions are irrelevant for the text question: the third four-high edition from 1609 is based on Q2 and in turn provides the template for the fourth four-high edition from 1623. In the first folio edition published in the same year, the editors do without the chorus at the beginning; for this reason some Shakespeare scholars have doubts about the authenticity of this edition.

The majority of today's editors of Romeo and Juliet use the second four-high edition as a more authentic text basis (copy text) , but also use the first four-high print in problematic areas and occasionally the first folio, especially with regard to performance-related details. Pressure to clarify. Since the path of the text from the author to the early print editions cannot be reconstructed with certainty in all places, such an eclectic procedure, in which text versions of subordinate print versions are used in cases of doubt, is common in almost all modern text editions.

The work and its reception history

As the most famous lovers in world literature, Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet are generally understood to be the embodiment of ecstatic love, which is so overwhelming that it makes the lovers forget the environment and its claims and transforms the individuality of both into a common identity. The intensity of this love finds its downside in the short duration and the tragic end.

Such a conception of Romeo and Juliet is based primarily on three scenes in the drama: the couple's first encounter while dancing at the feast of the Capulets (I, 5), the so-called balcony scene, the secret meeting at Juliet's window (II, 2) and the big farewell scene at dawn after the wedding night (III, 5).

Although these scenes are central to the play, they represent only part of the drama. The play is also about the old feud between the Montague and Capulet houses that gives the love story a deeper, tragic meaning, and the implications for it Action of the secular authority represented by the prince and the spiritual authority represented by Lorenzo.

Furthermore, the piece is characterized by the - much more extensive than the quarrel between the two houses - the individual world of the young men who spend their time together in their respective groups, roam the city, have fun together and fight with each other through their group membership identify the other group. Sexuality is important here, but it is frowned upon as love and is mocked because, as Romeo's example shows, it ultimately breaks the group identification and leads to leaving the group.

Another part of the stage world of this tragedy is ultimately also shaped by elements of comedy and cheerfulness, as they are presented above all by the solid and at the same time pragmatic life, love and marriage philosophy of Juliet's nurse and the mocking wit of Mercutio. These comedy-like passages are not separated from the serious events that triggered the tragedy, but represent a different view of the same thing and make it clear that an overwhelming love affair like the Romeos and Juliets has its comic aspects.

In the history of the reception of the work, the focus was on the three love scenes from the start; its effect and its interpretation has remained largely unchanged to the present. The other layers of meaning and components of the work, on the other hand, have proven to be problematic in the following epochs and have been absorbed in various ways.

The dominance of theater and performance history has remained constant in the history of the play's impact. With regard to the emphasis in the theater and in literary criticism or in the audience and readership, which in other Shakespeare plays is mostly different and sometimes changes from epoch to epoch, the emphasis in Romeo and Juliet is clearly and permanently on the popularity of this Work as a play.

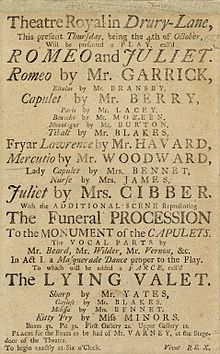

The continued popularity of Romeo and Juliet not only on the English stages, but also in Germany and the Netherlands, where the play had been performed by English comedians since the beginning of the 17th century, did not mean that the work was accepted in its original form. Although it was Shakespeare's most frequently performed drama from the mid-18th to the beginning of the 19th century, Romeo and Juliet was played exclusively in the form of adaptations for almost 200 years, all of which were aimed at lending greater weight to the poignant love story to reduce the remaining moments. For example, in the most played version by David Garrick, the original three encounters between Romeo and Juliet have been expanded to include a fourth, ultimate scene: Juliet wakes up before the poison can take effect on Romeo, and both only die after a long love dialogue.

In the middle of the 19th century, the English theater turned back to the original, which, however, had to be "cleaned up" by fading out the offensive and rough passages. This changed again in the 20th century; Now Shakespeare's bawdy was the order of the day and the hearty, suggestive parts were played out with verve . Likewise, moments that had previously been pushed back, such as the young men's macho games, were theatrically staged again. However, this did not imply a change in the theater towards purism of the history of literature: Even today, Romeo and Juliet is regarded as a play that gives the director complete freedom without losing its momentum and emotional expressiveness, whether it is in a modern Verona or in is presented in a renaissance ambience.

In literary criticism, there was initially a parallel development to the success story on stage. As early as 1598, Francis Meres praised the piece in the highest tones and equated it with the stage works by Plautus and Seneca. Although Samuel Pepys rated the play in 1662 as "the worst acted that I ever saw", the subsequent reviews were consistently positive. The long time authoritative English scholar and literary critic Samuel Johnson saw Romeo and Juliet as "one of the most pleasing of our author's performances" and the romantic critics, especially Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Hazlitt , outdid each other in their enthusiasm for the poetic expressiveness of this Shakespearean drama.

It was only with the increasing academization and scientification of literary criticism in the further course of the 19th century that the reception of the work began to become problematic when it came to sounding out the depth of the expressiveness of the text. The controversy, which lasted into the second half of the 20th century, was sparked primarily by the problem of what kind of tragedy the work represented and whether it actually corresponded to a recognized conception of tragedy. The question that kept coming up was whether the play was a fate tragedy or a character tragedy or neither. Equally controversial was the discussion about whether Romeo and Juliet as “star-crossed lovers” were mere puppets of the power of fateful chance or whether the dispute between the houses, in which Romeo and Juliet are both victims and a medium of reconciliation, was the thematic center of tragedy. Also discussed differently was the question of whether the two title characters were to blame for their downfall because they lived out their love excessively without any moderation, as Brother Lorenzo repeatedly admonished. Other interpreters interpreted the statement of the piece to the effect that every intense and excessive love as such inevitably conceals its fatal end.

In the meantime, when it comes to the question of the tragedy in Romeo and Juliet, the literary scholarly or critical discourse refrains from clearly assigning the play to a certain type of tragedy or measuring the work against the criteria of a specific tragedy norm, which are regarded as timeless. There is now broad consensus that different facets or aspects of the tragedy coexist in this drama. Some of today's literary scholars and critics assume that Shakespeare deliberately intended an ambivalence and ambiguity; It is generally assumed that Shakespeare, in the succession of the older English playwrights, worked with an open concept of tragedy: A tragedy thus presents a fatal case of the hero (s), which is caused by the capricious Fortuna , sometimes without meaning, sometimes as Retaliation for a fault.

Such a conception of tragedy, however, usually refers to the case of the powerful, whose fate affects an entire society. Against this background, it is considered significant that Shakespeare's play combines private love relationships with public disputes between families as a justification for the tragedy, as otherwise love could only be chosen as a suitable material for a comedy.

Ultimately, the reason for the historically long and still not fully overcome devaluation of Romeo and Juliet in the academic literary criticism lies in their approach. If the viewer concentrates entirely on the piece being performed during a performance, the historically-chronologically proceeding literary scholar or critic usually orientates himself on groups of works and literary lines of development. Against this background, Romeo and Juliet is often analyzed in literary studies from the perspective of Shakespeare's later tragedies such as King Lear or Hamlet and viewed from the point of view of what has not yet been achieved: There is a lack of subtle characterization, the differentiated play through of different topics or the artfully elaborated blank promises .

A different picture emerges, however, if one analyzes Romeo and Juliet from a more appropriate perspective on the background of the previously written stage works with regard to the suitability of the dramatic means employed for the task at hand. In his play Shakespeare no longer resorts to existing structures or techniques, but instead develops something new. He creates a tragedy out of a material previously reserved for comedy, and creates a wide range of linguistic means of expression, ranging from the humorous everyday prosaic of the servants to the imaginative conceits of the young masters to the equally excessive and formal bound lyrical language of lovers extends. Shakespeare's innovations include, in particular, the transformation of the concepts and the metrical forms and lyrical expressions of contemporary Pertrarkist love poetry into dramatic forms of expression.

For example, this becomes clear when Romeo and Juliet first met at the Festival of the Capulets. The first dialogue between the two is in the form of a sonnet with a coda attached , in which both are involved (I, 5,93-110). Romeo expresses the first quartet metaphorically in the role of a pilgrim who wants to reverently kiss a worshiped image of a saint (Juliet). Julia takes up this form and metaphor in the second quartet in order to initially limit the pilgrim to the touch of her hands while dancing. Then the speech and counter-speech become shorter until she allows him to kiss. The form of the poem is not an artful accessory, but at the same time reflects the dramatic event: advertising and response to it, development of a personal relationship within the framework of generally applicable conventions and social ceremonies; Abolishing and maintaining distance and finally the thematic representation of love as a religious act.

Shakespeare's drama also shows thematically and formally an abundance of the world previously unattainable in Renaissance tragedy in the juxtaposition and reconciliation of heterogeneous elements of drama and lyricism, tragedy and comedy, cynical and emotionally touched attitude or spontaneous and artificial style. The world of the lovers stands in a dramatically effective contrast to the hatred of their families, which they deny, but also to satirical - provocative or hearty-bitter reductions of love to the purely sexual. The topic of pure love is framed by a verbal comedy with a remarkable richness of frivolous or obscene jokes, whereby the confidants of the lovers, Mercutio and Julias Amme, bring this language level to bear.

Performance history

Various Shakespeare scholars, who consider a rather early drafting period to be likely, assume that the first public performance of the work probably took place in the theater in 1595 . Romeo and Juliet was extremely popular with English audiences from the start. This is not only indicated by the information on the title page of the first four-high print and the many quotations in other works of the Elizabethan era, but also by the other four-quarter versions that followed. The enduring popularity also continued beyond England : Romeo and Juliet were played early on by wandering English actors on the continent . Such performances are documented for the entire 17th century. A first demonstrable trace can be found in a Nördlinger performance from 1604; In 1625 a German version was published under the title Romio and Julietta .

When the theaters reopened during the restoration period after their closure during the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell , William Davenant arranged for the play to be performed again for the first time in 1662. A short time later, James Howard turned this performance into a tragic comedy with a happy ending, in which the lovers stay alive, and the drama was at times alternated between tragedy and tragic comedy. However, this adaptation by Howard is missing.

In addition to such adaptations of the original version, other versions were created at the same time in which the love story of Romeo and Juliet was placed in a new plot or frame of reference in other stage works. In 1679/1980, for example, a play by Thomas Otway was published under the title The History and Fall of Caius Marius , in which various passages from Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet are integrated into a new stage text. In Otway's play, the love scenes are transferred from the context of the Veronese family feud to the ancient times of the Roman civil war . Romeo is called Young Marius here , Juliet becomes Lavinia , and the quarrel takes place between patricians and plebeians . Otway's version was a great success and was performed until 1735. Theophilus Cibber (1744) and the well-known actor and playwright David Garrick (1748) resorted to Otway's ideas in their arrangements.

Cibber interwoven the text of Shakespeare's love tragedy with passages from his comedy Two Gentlemen from Verona . Garrick's adaptation proved to be more significant, however, as it ushered in a substantial return to the original text, which led to a period of triumphant success on the London stages. In Garrick's adaptation, all references to Rosaline are omitted, so that Romeo appears in love with Juliet from the start. Juliet is also a lot older with Garrick than with Shakespeare at the age of 18 and with him also wakes up at a time when Romeo is still alive, so that a long and heartfelt farewell scene was possible. In 1750 the play sparked a theatrical war between the theaters of Covent Garden and Drury Lane , which both brought the work to the stage with their best cast. Garrick's version and the associated tradition of relocating the beginning of great love to the period before the start of the drama lasted for almost a hundred years in theater history.

For the first time since 1679, Shakespeare's original version (albeit heavily abridged) returned to the stage in 1845. The performance at London's Haymarket Theater was initiated by American actress Charlotte Saunders Cushman . While in Elizabethan stage practice all female roles were still occupied by male actors, Cushman reversed this practice and played the male role of Romeo as an actress, recognized by the audience (her younger sister Susan took on the role of Juliet). Since this performance, no more important production has used a further redesign or adaptation of the original. Henry Irving's 1882 production at the Lyceum Theater in London clearly illustrates the style of decor that was preferred at the time (valuable costumes, long musical and dance interludes, impressive backdrops).

The performances from the 18th and early 19th centuries also had a predominantly didactic intention: By depicting the fate of Romeo and Juliet, who, according to the opinion of the time, were both responsible for their own actions, it should not only be made clear that love the judgment of the lovers can be blinded, but in particular it can be shown that disobedience to the will of the parents inevitably ends in disaster.

Garrick had already converted or deleted large parts of the original text in order to remove linguistic insinuations; in the arrangements from the 19th century this endeavor is shown to an even greater extent: any linguistic allusions to sexuality are eliminated from both the printed text editions and the staged versions. It was not until the middle of the 19th century that the original text of Shakespeare was reverted to without further linguistic changes since the performances with Charlotte Cushman, although revealing puns were still deleted.

Romeo and Juliet remained one of Shakespeare's most frequently performed works in the 20th century. Well-known productions since then include the 1934 Broadway production, directed by Guthrie McClintic, with Basil Rathbone as Romeo and Katharine Cornell as Juliet. In 1935 John Gielgud directed the New Theater in London and alternated Romeo and Mercutio with Laurence Olivier , Peggy Ashcroft played Juliet. In 1954, Glen Byam Shaw directed the Royal Shakespeare Company theater in Stratford-upon-Avon , starring Laurence Harvey as Romeo and Zena Walker as Juliet. A few years later, in 1962, Franco Zeffirelli staged the work at the same location with John Stride and Judi Dench in the leading roles.

Adaptations

In the literature

William Shakespeare's subject has been taken up by many writers. A list of some of the works based on the drama can be found under Romeo and Juliet (fabric) . The best-known adaptation in German-speaking countries is Gottfried Keller's novella Romeo and Juliet in the Village (1856). Keller relocates the story to Switzerland , the Italian lovers become two farmer children who perish in their fathers' quarrel.

Settings

For the first setting of Romeo and Juliet by Georg Anton Benda wrote Friedrich Wilhelm gods a version with a cheerful finale. The work was premiered in Gotha in 1776. The most important opera versions come from Vincenzo Bellini ( I Capuleti ei Montecchi 1830), Charles Gounod ( Roméo et Juliette 1867), and Heinrich Sutermeister ( Romeo and Juliet 1940). The best-known arrangements for the concert hall are the dramatic symphony Roméo et Juliette by Hector Berlioz , the fantasy overture by Tchaikovsky and the ballet music by Prokofiev . The musical West Side Story by Leonard Bernstein was a global success .

Movie

According to the Internet Movie Database, Romeo and Juliet has been filmed 30 times so far, although only those films were counted that directly cite Shakespeare's tragedy as a template. If you include all the films that also refer indirectly or parodically to the drama, the number would be much higher.

The most important films are:

- 1908: Romeo and Juliet by James Stuart Blackton . With Paul Panzer and Florence Lawrence

- 1912: Romeo and Juliet by Ugo Falena

- 1916: Romeo and Juliet by Francis X. Bushman and John W. Noble . With Francis X. Bushman and Beverly Bayne

- 1936: Romeo and Juliet by George Cukor . With Leslie Howard and Norma Shearer

- 1954: Romeo and Juliet by Renato Castellani . With Laurence Harvey and Susan Shentall

- 1968: Romeo and Juliet by Franco Zeffirelli . With Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey

- 1996: Romeo + Juliet by Baz Luhrmann . With Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes

- 2013: Romeo and Juliet by Carlo Carlei . With Douglas Booth and Hailee Steinfeld

Zeffirelli's version was filmed on the original locations in Verona and was the first film adaptation of the famous lovers as very young adolescents. In order to increase the authenticity, most of the actors were not famous theater actors, but rather mostly unknown actors at the time of the filming. Luhrmann's version is a radically modern reinterpretation of the piece with the means of video clip aesthetics.

The film Shakespeare in Love is an attempt to create a biographical background for the play: the author Shakespeare (played by Joseph Fiennes ) himself experiences a forbidden love and shapes it into his play. The end of the film shows the world premiere, with Shakespeare playing the title role of Romeo.

The Casa di Giulietta

In the Italian city of Verona , not far from Piazza delle Erbe , there is the house that, in the fiction of the story, is said to have been Juliet's childhood home. The Scaliger building in Via Cappello 27 originally belonged to the Del Cappello family (see the stone coat of arms in the arch of the backyard) and was used as a guesthouse until the last century ( 45 ° 26 ′ 31.4 ″ N , 10 ° 59 ′ 55 ″ E ) . The famous balcony in the courtyard was added later for tourists. Not far north of it (285 m walk) is the alleged house of the Montagues in Via Arche Scaligere.

The street sign of the Casa di Giulietta in Verona

Julia sculpture by Nereo Costantini under the balcony. (Two copies of it in Munich, Verona's twin city.)

Text output

- Total expenditure

- John Jowett, William Montgomery, Gary Taylor, and Stanley Wells (Eds.): The Oxford Shakespeare. The Complete Works. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, ISBN 978-0-199-267-187

- Jonathan Bate , Eric Rasmussen (Eds.): William Shakespeare Complete Works. The RSC Shakespeare , Macmillan Publishers 2008, ISBN 978-0-230-20095-1

- Charlton Hinman, Peter WM Blayney (Ed.): The Norton Facsimile. The First Folio of Shakespeare. Based on the Folios in the Folger Library Collection. 2nd Edition. WW Norton, New York 1996, ISBN 0-393-03985-4 .

English

- René Weis (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Bloomsbury, London 2012, ISBN 978-1-903436-91-2 .

- Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine (Eds.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. Folger Shakespeare Library. Simon and Schuster, New York et al. 2011, rev. 2011 edition, ISBN 978-1-4516-2170-9 .

- G. Blakemore Evans (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1984, ISBN 0-521-53253-1 .

- Jill L. Levenson (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-953589-7 .

German

- Dietrich Klose (ed.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. translated by August Wilhelm Schlegel . Reclam, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-15-000005-X .

- Ulrike Fritz (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg, Tübingen 1999, ISBN 3-86057-554-6 .

- Frank Günther (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. Bilingual edition. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-423-12481-2 .

- William Shakespeare. Complete Works. English German. Zweiausendeins, Frankfurt 2010, ISBN 978-3-86150-838-0 .

literature

- Hans-Dieter Gelfert : William Shakespeare in his time. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-65919-5 , pp. 295-298.

- Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells (Eds.): The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2nd Edition, Oxford 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 .

- Claudia Küster: Romeo and Juliet. Volume 6 of Sonja Fielitz's ed. Series: Shakespeare and No End. Kamp Verlag, Bochum 2005, ISBN 3-89709-387-1 .

- Dietrich Rolle : Romeo and Juliet. In: Shakespeare's Dramas. Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-15-017513-5 , pp. 99-128.

- Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th, revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 .

- Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 .

- Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, ISBN 0-393-31667-X .

- Didactic materials

- Frauke Frausing Vosshage: Explanations on William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet (Romeo and Juliet). (= King's explanations. Text analysis and interpretation. Volume 55). C. Bange Verlag , Hollfeld 2012, ISBN 978-3-8044-1994-0 .

Web links

- Romeo and Juliet In: Zeno.org (full text)

- Romeo and Juliet in Project Gutenberg ( currently not usually available for users from Germany )

- Verona, Romeo and Juliet Historical pictures and texts

- enotes (English)

- SparkNotes (English)

- Artur Sauer: Shakespeare's "Romeo and Juliet" in the arrangements and translations of German literature - dissertation 1915 on archive.org

Individual evidence

- ↑ See Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 309 f. See also Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, 5th rev. Edition, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 492 f. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells (Ed.): The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, Oxford 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , pp. 334 f. and G. Blakemore Evans (Eds.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1984, ISBN 0-521-53253-1 , Introduction , p. 6ff.

- ^ G. Blakemore Evans (Ed.): Romeo and Juliet. Cambridge 1984, p. 7. See also Günter Juergensmeier (Ed.): Shakespeare and his world. Galiani, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3869-71118-8 , p. 192. Jürgensmeier assumes that Shakespeare only used William Painter's version for very few details and possibly only used Brooke's long poem as the only source for his tragedy.

- ↑ Brooke uses the name Romeo only in a single place as a rhyme for Mercutio in line 254 of the poem. See Arthur Brooke: The Tragicall History of Romeus and Juliet . Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ↑ See Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 309 f. See also Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, 5th rev. Edition, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 492 f. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells (Ed.): The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, Oxford 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , pp. 334 f. and G. Blakemore Evans (Eds.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1984, ISBN 0-521-53253-1 , Introduction , p. 6ff. See also Ryan McKittrick: A comparison of Arthur Brooke's "Romeus and Juliet" and Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet . Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ↑ See Dante, Divine Comedy, Purgatory, Sixth Canto (Divina Commedia, Purgatorio, canto sesto), pp. 106-108. See also René Weis (ed.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Bloomsbury, London 2012, ISBN 978-1-903436-91-2 , Introduction: Sources .

- ↑ See Stanley Wells , Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. corrected reprint. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1997, ISBN 0-393-31667-X , p. 288. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells (Ed.): The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2nd Edition, Oxford 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 333, and Jill L. Levenson (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-953589-7 , pp. 96ff.

- ↑ See Stanley Wells , Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. corrected reprint. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1997, ISBN 0-393-31667-X , p. 288. See also Ina Schabert: Shakespeare Handbuch . Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 492. Cf. also in detail the introduction by Jill L. Levenson to the by her ed. Oxford edition of Romeo and Juliet. Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-953589-7 , pp. 96-107, and G. Blakemore Evans (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1984, ISBN 0-521-53253-1 , Introduction , pp. 1 f.

- ↑ See René Weis (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Bloomsbury, London 2012, ISBN 978-1-903436-91-2 , Introduction, p. 39.See also MacDonald P. Jackson: Editions and Textual Studies. In: Stanley Wells (Ed.): Shakespeare Survey 38, Shakespeare and History. Cambridge University Press, 1985, p. 242. See also JM Tobin: Nashe and Romeo and Juliet . Notes & Queries No. 27, 1980. For the first documented performance of the work, cf. Hans-Dieter Gelfert : William Shakespeare in his time. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-65919-5 , p. 295.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Thomas Thrasher: Understanding Romeo and Juliet. Lucent Books, San Diego 2001, ISBN 1-56006-787-X , pp. 34 f. Thrasher, like other Shakespeare scholars, assume that it was composed between 1592 and 1594. As an indication of such a dating, they refer on the one hand to the bubonic plague prevailing during this period and the closure of public theaters, which gave Shakespeare sufficient time to write the work. In addition, they base their assumption on the publication of two poems by Shakespeare ( Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucre ) and the new stage performance of nine Shakespeare works immediately after the end of the bubonic plague and the reopening of the theater at the turn of the year 1594/95. In addition, they refer to the numerous sonnets in the piece, which they believe were also composed during this period, as well as the sonnets dedicated to the Earl of Southampton.

- ↑ See in detail Claudia Küster: Romeo and Juliet. Volume 6 of Sonja Fielitz's ed. Series: Shakespeare and No End. Kamp Verlag, Bochum 2005, p. 19 f.

- ↑ The editors of Folger-Shakespeare ignore in their exception - with the exception of a single passage reprinted in Q2 - the Ducktext of Q1 completely when issuing and only use Q2 as the textual basis for their edition, since in their opinion the non-authoritative text version of Q1 is too different from the Q2 version that you consider to be exclusively authentic. See Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine (Eds.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. Folger Shakespeare Library. Simon and Schuster, New York et al. 2011, rev. Edition 2011, ISBN 978-1-4516-2170-9 , An Introduction to This Text , p. 14 ff.

- ↑ The abbreviations in Q1, which primarily concern monologues and lyric passages, are also seen in more recent Shakespeare research as an indication of the Elizabethan public taste. Audiences at the time probably preferred comic scenes or action-packed scenes with violence, while pausing or lyrical passages were seen as too lengthy. Compare with Claudia Küster: Romeo and Juliet. Volume 6 of Sonja Fielitz's ed. Series: Shakespeare and No End. Kamp Verlag, Bochum 2005, p. 18.

- ↑ See Stanley Wells , Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. corrected reprint. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1997, ISBN 0-393-31667-X , pp. 288 ff. See also Claudia Küster: Romeo and Juliet. Volume 6 of Sonja Fielitz's ed. Series: Shakespeare and No End. Kamp Verlag, Bochum 2005, p. 17 f. See also Ina Schabert: Shakespeare Handbook . Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 492, and Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 310 f. See also in detail the introduction by Jill L. Levenson to the Oxford edition of Romeo and Juliet which she edited . New edition. Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-953589-7 , pp. 107-125.

- ↑ See Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. 2nd Edition. 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 334. See also Ulrich Suerbaum : Der Shakespeare-Führer. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 311, as well as Claudia Küster: Romeo and Juliet. Volume 6 of Sonja Fielitz's ed. Series: Shakespeare and No End. Kamp Verlag, Bochum 2005, p. 18.

- ↑ See in detail Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 311-313. See also Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, 5th rev. Edition, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 497.

- ↑ See Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 313 f. See also Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, 5th rev. Edition, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 494 ff. And 497 f.

- ↑ See Thomas Thrasher: Understanding Romeo and Juliet. Lucent Books, San Diego 2001, ISBN 1-56006-787-X , p. 39.

- ↑ See in more detail the discussion of the genre issue with Claudia Küster: Romeo and Juliet. Volume 6 of Sonja Fielitz's ed. Series: Shakespeare and No End. Kamp Verlag, Bochum 2005, pp. 89-101. See also in terms of reception history the remarks by Ulrich Suerbaum : Der Shakespeare-Führer. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd rev. Edition 2015, p. 314 f.

- ↑ See Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 315-317. See also Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, 5th rev. Edition, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 494 ff. And Jill L. Levenson (ed.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-953589-7 , Introduction , p. 49 ff. See also Hans-Dieter Gelfert : William Shakespeare in his time. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-65919-5 , p. 295 ff.

- ↑ See Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 317 f. See also Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, 5th rev. Edition, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 496 f. See also for a fuller Jill L. Levenson (ed.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-953589-7 , Introduction , pp. 50-68.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, 5th rev. Edition, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 495 f.

- ↑ See Thomas Thrasher: Understanding Romeo and Juliet. Lucent Books, San Diego 2001, ISBN 1-56006-787-X , p. 35.

- ^ Albert Cohn: Shakespeare in Germany in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. 1865, p. 115 f. and 118 f.

- ↑ See Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, 5th rev. Edition, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 497.

- ↑ See Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, 5th rev. Edition, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 497. See also Claudia Küster: Romeo and Juliet. Volume 6 of Sonja Fielitz's ed. Series: Shakespeare and No End. Kamp Verlag, Bochum 2005, pp. 139 ff. See also Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ Richard W. Scooch: Pictorial Shakespeare . In Stanley Wells, Sarah Stanton (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage . 2002, p. 62 f.

- ↑ See Claudia Küster: Romeo and Juliet. Volume 6 of Sonja Fielitz's ed. Series: Shakespeare and No End. Kamp Verlag, Bochum 2005, p. 139 ff.

- ↑ On the various productions of Romeo and Juliet in the second half of the 20th century, see also the detailed systematic description in Russell Jackson: Shakespeare at Stratford: Romeo and Juliet. The Arden Shakespeare in Association with the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Thomas Learning, London 2003, ISBN 1-903436-14-1 , Introduction , pp. 13-25.

- ^ Ina Schabert: Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, p. 498.