Hero and Leander

Hero ( ancient Greek Ἡρώ Hērṓ ) and Leander ( Λέανδρος Léandros ) are two characters from Greek mythology . They are among the most famous lovers in European literature. According to legend, Hero was a priestess of Aphrodite in Sestos on the western bank of the Hellespont Strait . Her lover Leander lived in Abydos on the opposite bank of Asia Minor . Since he could only visit Hero in secret, he swam across the Hellespont every night. A beacon that Hero lit in a tower or an oil lamp or torch she used there showed him the way. However, once he got lost in a storm that put out the fire and drowned. The following morning Hero discovered his corpse washed ashore on the bank and fell from the tower to his death.

The material is first used in the 1st century BC. Chr. Attests its origin is unknown. The first detailed adaptation comes from the poet Ovid , who wrote a fictional letter from Leander to Hero and their answer and included it in the collection of his heroid letters . Around the middle or in the second half of the 5th century, the poet Musaios presented the story in a Greek epyllion (short epic). Mentions in imperial literature and representations in the visual arts indicate the continued popularity of the legend.

In modern times, the legend developed a strong aftermath. The modified version of the folk song There were two royal children was particularly widespread . Of the numerous literary adaptations, the best known are an epic poem by Christopher Marlowe , a ballad by Friedrich Schiller and Franz Grillparzer's tragedy Des Meeres und der Liebe Wellen . In addition to poets and writers, visual artists and composers also took up the motif of the tragic love story. Many paintings and sculptures as well as a series of operas, cantatas , songs and instrumental compositions bear witness to the persistent fascination of the legend. The material was sometimes alienated in travesties and parodies .

Antiquity

The local conditions

The Dardanelles Strait, called the Hellespont in ancient times, separates the European Gallipoli peninsula from Asia Minor. It connects the Aegean Sea, part of the Mediterranean, with the Sea of Marmara , which is connected to the Black Sea via the Bosporus . On the surface, water flows continuously from the Black Sea into the Mediterranean. This current is strong and increases in narrow places and with north winds. In ancient times, the narrowest point was between the port cities of Sestos on the European and Abydos on the Asian shore; today the conditions are somewhat different due to the landings . The distance between these two ports is given by the ancient geographer Strabo as 30 stages . The descriptions of Polybios and Strabo show that due to the strength and course of the current in the area of this narrowing it was impossible to get directly from one port to the other. On the Asian side, outside the sheltered harbor of Abydos, stormy seas had to be expected. In addition, Sestos could not be reached directly from the opposite coast because the current did not touch its port, but only broke onto the shore a little below the city.

Therefore, there were suitable berths on the two coasts especially for the crossing to the other shore at some distance from the ports of the two cities. The place suitable for embarkation was on the Asia Minor side, eight stadiums northeast of Abydos. On the European side, the berth was on a rocky coast, from Sestos a little southwest towards the Aegean Sea. Thus the two places designated for this shipping traffic were further apart than the ports of the cities. Each of them was marked by a tower. The Asian tower had no name, the European one was called "Tower of the Hero". Those who wanted to go from Abydos to Sestos first followed the shore northeast of the coast and thus reached the Asian tower. This was located where the main current coming from the Marmara Sea meets the bank, with part of the water being diverted and then flowing southwest across the European side. This cross current carried a ship or a swimmer diagonally across to the European coast, past Sestos to the landing-place marked by the Herotower. From there you had to go ashore to Sestos. To return you could embark at the Herotower and then have the cross-current that began there carried directly to the city of Abydos. The Asian tower was therefore not needed.

Despite the two helpful currents, however, crossing the Hellespont was dangerous for a swimmer, especially at night. The current could get fast in places and in bad weather you could get lost. The Heroturm, which indicated the landing site to the boatmen, was also an indispensable guide for a swimmer coming from the Asian shore. In the Roman Empire it served as a lighthouse. Apart from the legend of Hero and Leander, the ancient sources do not mention any crossing of the strait by swimmers.

The literary adaptations

The story of Hero and Leander is attested late in antiquity: The literary tradition continues in the late 1st century BC. A and the surviving pictorial representations all come from the Roman Empire . It is therefore certain that the original version of the story comes from the epoch of Hellenism , a time in which fiction literature satisfied a growing interest in "romantic" subjects and tragic love adventures. Not only because of its late creation, but also for reasons of content, the story of Hero and Leander is not part of the classic Greek hero legend. The two figures are simple mortals, not heroes of semi-divine origin. The action only takes place between them, in a purely human milieu; no miracles happen, no heroic deeds are performed, and the gods do not intervene. Therefore, this material is only marginally part of Greek mythology. It shows more in common with the constellations of Hellenistic novels than with the myths of the archaic period.

According to the prevailing view today, the legend has a local origin. It apparently originated in the area of Sestos and was initially spread orally. According to a speculative research opinion, the origin motive was aitiological , that is, the narrative was originally conceived for the purpose of historically explaining a present fact by inventing a fabulous origin story that goes with it. Accordingly, it was the dangerousness of the ship passage and the beacon at Sestos that gave rise to the motif of the fateful extinction of the light required for orientation. In such aitiological sagas, the action is often embedded in a religious context. In the present case this would be the cult of the goddess of love Aphrodite, because Hero is presented as her priestess. However, the aitiological interpretation cannot be proven. There is also the possibility that the reason for the creation of the saga was a historical event.

The first mentions of the incident assume that it was already known to the reading public. Accordingly, the originally local legend spread quickly in the Roman Empire and was at least familiar to the educated at the beginning of the imperial era. Classical scholars have tried to reconstruct the lost Hellenistic original version, but no such hypothesis has found general approval. In older research, a connection with the construction of the first lighthouses was assumed and the legends were therefore formed in the 3rd century BC. Set; at that time the Heroturm was probably put into operation as a lighthouse. Today such speculations are rejected; there is now a tendency towards late dating and it is assumed that the legend did not exist until the 1st century BC. BC, not long before its reception in literary works began.

The first author to refer to the legendary event was Virgil . In his probably 29 BC When he completed the poem Georgica , which deals with agriculture, he warned of the negative effects of the mating instinct in horse and cattle breeding. He emphasized the need to keep bulls from cows and stallions from mares. Both in livestock husbandry and in game it has been shown that sexual arousal leads to destructive behavior. In humans, too, uninhibited erotic desire is fatal. The fate of the young man for whom “cruel love” (durus amor) kindles a tremendous fire and the marrow glows through serves as a deterrent example in Virgil's verses . It incites him to swim through the wild waters in a storm at night. Nothing can stop him from the daring undertaking that costs him his life: He thinks neither of the misery of his parents who will lose their son, nor of the future of the beloved who will die for him. He throws himself and others into misery. Leander is not mentioned here by name, but he is obviously referred to. Servius , an influential fourth-century commentator on Virgil, remarked that the poet had not given Leander's name because the story was known. Virgil probably omitted the attribution to underline the supra-individual validity of his judgment. At this point it is not about an individual fate, but rather the young man, who is robbed of his senses by “cruel love”, represents a type. The decidedly negative assessment of erotic attraction is striking. The "blind" love (caecus amor) appears here as a destructive power that drives people and animals alike into a fateful madness. The person who surrenders to such passion instead of curbing it behaves, according to Virgil's judgment, no different from a fiery animal.

The poet Horace , a somewhat younger contemporary of Virgil, named the strait "between the neighboring towers" as a possible obstacle to travel when returning to Italy from the east. He was evidently alluding to the weather conditions there, which, according to the Leander legend, were doomed. In his geography , on which he was working around the time of the birth of Christ, Strabon casually mentioned the "Tower of the Hero" when describing the Hellespont; this term was already common at the time. The oldest surviving tradition also dates from around this time, in which Leander is named as the drowned swimmer and Hero as his lover. These are two epigrams of Antipater of Thessalonica that were included in the Anthologia Palatina . In brief words, Antipater recalled the young man's death in the storm and the extinction of the light as the cause of the misfortune. According to him, the ruins of the apparently destroyed Hero Tower could still be viewed in his time.

The oldest extensive literary adaptation of the material comes from Ovid. He wrote the Heroides , a collection of twenty-one letter poems in elegiac distiches , in which he let famous mythical figures speak. In the first fifteen fictional letters, women turn plaintively to their lost spouse or lover; the last six are three pairs of letters in which a man writes to his beloved and she replies to him. Leander addressed the eighteenth letter to Hero, the nineteenth is her answer.

Musaios, the late antique poet of the Epyllion, referred to in the handwritten tradition of his work as the grammarian, The story of Hero and Leander , is otherwise unknown. His work consists of 343 hexameters and is in the tradition of Hellenistic narrative poetry; individual, self-contained, broad-based scenes are strung together. The portrayal leads from the couple's first meeting to the catastrophe.

Middle Ages and Early Renaissance

In the Middle Ages, the material was only known from Ovid's work in western and central Europe. The lost Epyllion of Musaios was not discovered until the time of Renaissance humanism .

Editing or mentioning:

- Balderich von Bourgueil : treatment of the material in a mythological poem fragment in distiches (1099/1102)

- Dante , Divina Commedia : Mention of Leander in Purgatorio 27.2 and 28.73-75

- Ovide moralisé 4,3150–3731 (allegorizing treatment of works by Ovid, around 1316/1328)

- Francesco Petrarca : Il trionfo dell'amore , part 3 (poem, 1340/1344)

- Christine de Pizan : L'epistre d'Othéa à Hector 42 (didactic prose novel , around 1400) and Le Livre de la Cité des Dames , Part 2 No. 58 (didactic prose compendium, revision of Boccaccio's De mulieribus claris , 1405)

- Anonymous : Hero and Leander Probably at the beginning of the 14th century in the Alemannic region resulting Mare . The author went directly to Ovid.

Early modern age

Poetry, epic, novel

- Garcilaso de la Vega : Pasando el mar Leandro el animoso (The brave Leander crosses the sea) (poem)

- Bernardo Tasso : Favola di Leandro e d'Hero (poem, published 1534/1537)

- Clément Marot : Histoire de Léandre et Héro (poem, published in 1541)

- Hans Sachs : Historia. The unfortunate love Leandri with fraw Ehron (song, 1541)

- Juan Boscán Almogávar : Hero y Leandro (poem)

- Christopher Marlowe : Hero and Leander (epic poem, unfinished)

- Thomas Nashe : Prayse of the Red Herring or Lenten stuffe (Prosaburlesque, utilizes the material; published in 1599)

- Luis de Góngora : La fábula de Leandro y Hero (poem, around 1600)

- George Chapman : The Divine Poem of Musaeus (poem, completion of the unfinished epic poem by Christopher Marlowe; printed 1616)

- Gabriel Bocángel y Unzueta: La fabula de Leandro y Hero (poem, published 1627)

- Francesco Bracciolini dall'Api: Ero e Leandro (fable, published 1630)

- Francisco de Quevedo : Ero y Leandro (novel)

- Robert Herrick : Leander's Obsequies (poem, published 1648)

- Francisco de Trillo y Figueroa: Fábula de Leandro (poem, published in 1652)

- Paul Scarron : Léandre et Héro (burlesque ode, published in 1656)

- Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty : Leander and Hero (poem, 1769/70)

- Daniel Schiebeler : Leander and Hero (ballad as a travesty of ancient material, published in 1770)

- Jean-François de La Harpe : Hero (poem)

- Friedrich Hölderlin : Hero (poem, 1788)

- Friedrich Schiller : Hero and Leander (Ballade, 1801)

drama

- Jehan Baptista Houwaert: Leander ende Hero (part of Den handel der amoreusheyt , 1583)

- William Shakespeare : As you like it 4,1,100-108 (comedy; myth is mentioned therein; first attested performance 1603)

- Ben Jonson : Bartholomew Fair 5.4 (comedy; Hero and Leander are parodied in a puppet show. First performance 1614 in London)

- Antonio Mira de Amescua: Hero y Leandro (Drama, Lost)

- Gabriel Gilbert : Léandre et Héro (Tragedy, printed 1667)

- William Wycherley (?): Hero and Leander (burlesque travesty, printed 1669)

- Johann Baptist von Alxinger: Hero (tragedy, 1785)

- Jean-Pierre Clovis de Florian: Héro et Léandre (dramatic monologue, published in 1786)

Visual arts

- Tiziano Minio: "Thetis helps Leander" (marble relief, 1537/1539; Loggetta, Piazza San Marco, Venice)

- Hendrick Goltzius : "Leander" (engraving, around 1580)

- Annibale Carracci: "Hero and Leander" (fresco, 1597/1600; Galleria, Palazzo Farnese, Rome)

- Peter Paul Rubens : "Hero and Leander" (painting, around 1605; Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven)

- Domenico Fetti: "Hero and Leander" (painting, around 1610/1612; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

- Anthonis van Dyck (?): "Hero and Leander" (painting, around 1618/1620; sold in New York in 1978)

- Jan van den Hoecke: "Hero mourns the dead Leander" (painting, around 1635/1637; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

- Giacinto Gimignani: "Hero and Leander" (painting, 1637 (?); Uffizi, Florence)

- Gillis Backereel: "Hero laments the dead Leander" (painting from the 1640s; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

- Nicolas Régnier : "Hero and Leander" (painting, around 1650; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne)

- Giulio Carpioni: "Leander's body is pulled out of the sea" (painting; Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, Budapest)

- Angelika Kauffmann : "Hero and Leander" (painting, 1791)

music

- Thomas Campion : Shall I come, if I swim? (Song, 1601)

- John Wilbye : Weep, weep, mine eyes (Madrigal, 1609)

- Nicholas Lanier : Hero and Leander (musical recitative, around 1625/1628?)

- Francesco Antonio Pistocchi: Il Leandro (opera as "lyrical drama", first performance in 1679 in Venice; other version: Gli amori fatali , first performance in 1682 in Venice)

- Georg Friedrich Handel : Ero e Leandro (Italian solo cantata [HWV 150]; 1707)

- Vincenzo II De Grandis: Le lagrime d'Ero (Cantata)

- Louis-Nicolas Clérambault : Léandre et Héro (Cantata, 1713)

- Alessandro Scarlatti : Ero e Leandro (Cantata)

- Pierre de La Garde: Léandre et Héro (third act of the opera ballet La journée galante , first performance in 1750 in Versailles)

- René von Béarn, Marquis of Brassac: Léandre et Héro (opera as "lyrical tragedy", first performance in 1750 in Paris)

- Nicolas Racot de Grandval: Léandre et Héro (Cantata)

- Niccolò Zingarelli: Ero (oratorio, first performed in Milan in 1786)

- William Reeve: Hero and Leander (Burletta, musical comedy, world premiere in 1787 in London)

- Johann Simon Mayr : Ero (cantata for voice and orchestra) and La aventura di Leandro (cantata)

- Victor Herbert: Hero and Leander op.33 (symphonic poem, 1901)

Modern

The fact that a new version evidently emerged that shifted the scene from the Hellespont to the Bosporus is evidence of the survival of the legend outside of fiction, art and science. A built in the 18th century lighthouse on a small island Bosphorus in Istanbul , the Turkish "Maiden Tower" is called, is named in Europe Maiden's Tower received.

Poetry, epic, novel

- George Gordon Byron : Written after Swimming from Sestos to Abydos (poem, 1810) and The Bride of Abydos: A Turkish Tale 2,1 (poem, therein the myth mentioned; published 1813)

- John Keats : On a Leander Which Miss Reynolds, My Kind Friend, Gave Me (Sonnet, 1816/1817)

- Leigh Hunt: Hero and Leander (poem, published 1819)

- Thomas Hood: Hero and Leander (poem, published 1827)

- Thomas Moore: Hero and Leander (poem, published 1828)

- Alfred Lord Tennyson : Hero to Leander (dramatic monologue, published in 1830)

- Francis Reginald Statham: Hero (poem, published 1870)

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti: Hero's Lamp (Sonnet, no.88 in the expanded version of the episode The House of Life , published in 1881)

- Madison Cawein: Leander to Hero (poem, published 1889)

- Otto Sommerstorff : Hero and Leander (poem, 1900)

- John Drinkwater: The Death of Leander (poem, published 1906)

- Brookes More: Hero and Leander (poem, published 1926)

- Frank Morgan: Hero and Leander (poem, published 1926)

- James Urquhart: Hero and Leander (poem, published 1928)

- Malcolm Cowley: Leander (poem, published 1929)

- Alfred Edward Housman: Tarry delight, so seldom met (poem, published 1936)

- Erich Maria Remarque : The Night of Lisbon (novel, 1963; the legend is an important element in it)

- Heinz Erhardt : Hero and Leander (humorous poem)

- Stein Mehren : Hero og Leander (poem, published 1973)

- Milorad Pavić : The Inner Side of the Wind or The Novel by Hero and Leander (Novel, 1995)

drama

- Franz Grillparzer : The waves of the sea and the waves of love (tragedy in verse, first performance in 1831 in the Burgtheater, Vienna)

- Louis Gustave Ratisbonne: Héro et Léandre (Tragedy, published in 1859)

- Harold Kyrle Bellew: Hero and Leander (poetic drama, first performed in Manchester in 1892)

- Edmond Haraucourt: Héro et Léandre (dramatic poem with music by Paul and Lucien Hillemacher, first performed in Paris in 1893)

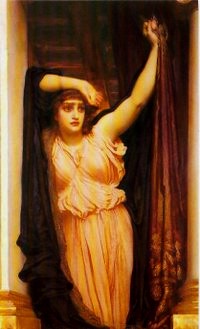

Visual arts

- John Flaxman : Drawings for Musaios' Epyllion (1805)

- John Gibson : Heros Encountering Leander (marble relief, around 1822; Duke of Devonshire's Collection, Chatsworth)

- William Etty : The Farewell to Hero and Leander (painting, 1827; Tate Gallery, London)

- William Turner : The Farewell to Hero and Leander (painting, 1837; National Gallery, London)

- Honoré Daumier : Leander (lithograph, 1842)

- Théodore Chassériau : The Last Meeting of Hero and Leander ( Grisaille )

- William Henry Rinehart : Leander (marble statuette, completed 1865; original lost, copy in the Baillière collection, Baltimore) and Hero (marble statuette, 1866/1867; Peabody Institute, Baltimore)

- John La Farge : Swimmer - Leander, Study of a Swimmer, Twilight (watercolor, 1866; Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven)

- Edward Armitage: Hero Kindles the Light (painting, 1869)

- Henry Hugh Armstead: Hero and Leander (stone relief, around 1875; Tate Gallery, London)

- Evelyn Pickering de Morgan: Hero is waiting for Leander (painting, 1885)

- Frederic Leighton : Heros Last Wait and Leander Drowned (two paintings, around 1887; City Art Gallery, Manchester)

- Eugène-Antoine Aizelin: Leander (marble statue, 1890)

- Henry Scott Tuke: Leander (painting, 1890)

- Gaston-Victor-Edouard Gaston-Guitton: Leander (marble statue)

- Aristide Maillol: Hero and Leander (woodcut, 1893)

- Charles Edward Perugini: Hero (painting, 1914)

- Paul Gasq: Hero and Leander (marble high relief)

- Paul Manship: Leander (bronze statuette, 1955; Minnesota Museum of Art, St. Paul)

- Ferdinand Keller: Hero and Leander (painting, 1880)

music

Opera, ballet, modern dance

- Louis Milon (choreographer): Héro et Léandre (ballet, first performance 1799 in Paris)

- William Leman Speech: Hero and Leander (Burletta, first performed in London in 1838)

- Giovanni Bottesini : Ero e Leandro (opera, libretto by Arrigo Boito , first performed in Milan in 1879)

- Arthur Goring Thomas: Hero and Leander (musical scene, first performed in London in 1880)

- Arthur Coquard: Hero and Leander (Lyric Scenes, 1881)

- Ernst Frank : Hero (opera, libretto by Ferdinand Vetter , first performance 1884 in Berlin)

- Luigi Mancinelli : Ero e Leandro (opera as lyrical tragedy, libretto by Arrigo Boito, first performance in Madrid in 1897)

- Ludvig Schytte : Hero (opera, libretto by Poul Levin, first performance in Copenhagen in 1898)

- Hermann Schroeder : Hero and Leander (Opera, 1950)

- Juan Corelli (choreographer): Héro et Léandre (ballet)

- Gerhard Wimberger : Hero and Leander (dance drama, 1963)

- Günter Bialas : Hero and Leander (opera, world premiere in 1966 in Mannheim)

Other musical works

- Désiré Beaulieu : Hero (Cantata, 1810)

- Fanny Hensel : Hero and Leander (Lied, 1832)

- Robert Schumann : In the night (composition for piano, Phantasiestücke opus 12; the stormy night of Leander's death is evoked, 1837)

- Ödön Péter József de Mihalovich: Hero and Leander (orchestral ballad, 1875)

- Walter Cecil Macfarren: Hero and Leander (Overture, first performed in Bristol 1878)

- Charles Harford Lloyd: Hero and Leander (Cantata)

- Alfredo Catalani: Ero e Leandro (symphonic poem, first performed in Milan in 1885)

- Victor Herbert : Hero and Leander (symphonic poem, first performed in 1901 in Pittsburgh)

- Wolfgang von Waltershausen: Hero and Leander (symphonic poem, opus 22, first performance 1925 in Munich)

- Berthe di Vito-Delvaux: Héro et Léandre (Cantata, opus 11, text by Felix Bodson, 1940)

- Robert Heger : Hero and Leander (symphonic poem)

- Carl Friedemann : Symphonic Prologue to Hero and Leander (Symphonic Poetry)

Text editions and translations

- Karlheinz Kost (Ed.): Musaios: Hero and Leander. Introduction, text, translation and commentary. Bouvier, Bonn 1971, ISBN 3-416-00655-0

- Hans Färber (Ed.): Hero and Leander. Musaios and the other ancient evidence. Heimeran, Munich 1961 (compilation of ancient and medieval sources with German translation)

- Horst Sitta (transl. / Ed.): Musaios, Hero and Leander , in: Greek Kleinepik, ed. Manuel Baumbach, Horst Sitta, Fabian Zogg, Tusculum Collection , 2019 (Greek-German)

literature

- Manuel Baumbach : Hero and Leander. In: Maria Moog-Grünewald (Ed.): Mythenrezeption. The ancient mythology in literature, music and art from the beginnings to the present (= Der Neue Pauly . Supplements. Volume 5). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2008, ISBN 978-3-476-02032-1 , pp. 352-356.

- Jane Davidson Reid: The Oxford Guide to Classical Mythology in the Arts, 1300-1990s , Volume 1. Oxford University Press, New York / Oxford 1993, pp. 573-577

- Anneliese Kossatz-Deissmann: Hero et Leander . In: Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC), Volume 8. Artemis, Zurich / Düsseldorf 1997, ISBN 3-7608-8758-9 , Volume 8.1, pp. 619–623 (text) and Volume 8.2, pp. 383-385 ( Images)

- Silvia Montiglio: The End? The Death of Hero and Leander from Antiquity to the Rediscovery of Musaeus in Western Europe. In: Antiquity and the Occident . 62, 2016, pp. 1–17

- Hero and Leander . In: The Gazebo . Issue 9, 1879 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

Web links

- Franz Grillparzer : The sea and the waves of love in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Friedrich Schiller: Hero and Leander .

Remarks

- ↑ Ludolf Malten : Investigations in the history of motifs on legends research III. Hero and Leander. In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 93, 1950, pp. 65–81, here: 71–73.

- ↑ Ludolf Malten: Investigations in the history of motifs on legends research III. Hero and Leander. In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 93, 1950, pp. 65–81, here: 73–77.

- ↑ Virgil, Georgica 3.209 to 257.

- ↑ Virgil, Georgica 3.258 to 263.

- ^ Servius, In Vergilii georgica commentarius 3,258.

- ↑ See also Gary B. Miles: Virgil's Georgics , Berkeley 1980, pp. 197-205; Willi Frentz: Mythological in Virgil's Georgica , Meisenheim am Glan 1967, pp. 124–129. See Enrica Malcovati : Ero e Leandro. In: Enciclopedia Virgiliana , Vol. 2, Rome 1985, p. 371 f.

- ↑ Horace, Epistulae 1, 3, 3–5.

- ↑ Strabo, Geography 13,22,591.

- ↑ Anthologia Palatina 7,666 and 9,215.

- ↑ Text and translation by Hans Färber (ed.): Hero and Leander. Musaios and the other ancient testimonies , Munich 1961, pp. 76–83 and 111.

- ^ Douglas Bush: Mythology and the Renaissance Tradition in English Poetry , New York 1963, p. 300.

- ^ Douglas Bush: Mythology and the Romantic Tradition in English Poetry . Cambridge MA 1937, pp. 211-218.

- ^ Douglas Bush: Mythology and the Renaissance Tradition in English Poetry , New York 1963, p. 302.

- ^ Douglas Bush: Mythology and the Renaissance Tradition in English Poetry , New York 1963, p. 304.

- ↑ Douglas Bush: Mythology and the Renaissance Tradition in English Poetry , New York 1963, pp. 179, 548.

- ↑ Douglas Bush: Mythology and the Renaissance Tradition in English Poetry , New York 1963, pp. 190 f.

- ^ Douglas Bush: Mythology and the Romantic Tradition in English Poetry . Cambridge MA 1937, p. 558.

- ↑ Otto Sommerstorff: Hero and Leander. Dramatic poem in one act. In: Scherzgedichte , 6th edition, Berlin 1911, printed in: Robert Gernhardt , Klaus Cäsar Zehrer (eds.): Hell and Schnell , Frankfurt am Main 2004, p. 355 f.

- ^ Douglas Bush: Mythology and the Romantic Tradition in English Poetry . Cambridge MA 1937, p. 590.

- ^ Douglas Bush: Mythology and the Romantic Tradition in English Poetry . Cambridge MA 1937, p. 574.