Giovanni Bottesini

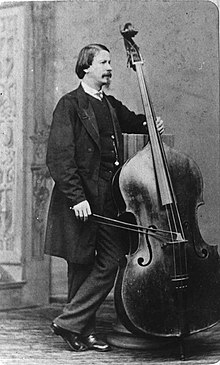

Giovanni Bottesini (born December 22, 1821 in Crema , † July 7, 1889 in Parma ) was an Italian double bass player , conductor and composer . His name went down in music history mainly because he conducted the world premiere of Giuseppe Verdi's opera Aida on December 24, 1871 in Cairo . Bottesini was also considered the leading double bass virtuosoits time. He wrote a large part of his compositions for this instrument, most of these pieces are still present in the repertoire of double bass soloists.

Origin, youth and education

Childhood and first lessons in Crema

Much of the information about Bottesini's youth is unclear and sometimes contradictory. While primary sources - such as corresponding entries in the baptismal register - were not or could not be consulted by the musician's early biographers, the "right-wing bohémien" (according to Friedrich Warnecke), later known worldwide, offered sufficient material for transfigurative, speculative and partly fictitious representations . The traveling virtuosos played a role in the musical life of the 19th century (the legendary vitae of Niccolò Paganini or Franz Liszt are famous to this day ), which in many ways resembles that of contemporary pop stars . The numerous reports that have come down to us therefore come not only from knowledgeable contemporaries, but to an at least as large extent from the "gossip press" of the time.

Even with regard to the exact date of birth and the musician's baptismal name, the information deviates considerably from one another; In addition to the birthday mentioned at the beginning, December 24th and the years 1822 or 1823 are often mentioned. Only the works created on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Bottesini's death, i.e. 1989, under the direction of the music historian Luigi Inzaghi , are characterized by extensive source work. The Latin entry in the church book of the Cathedral of Crema therefore notes under the date "23 Xbris [decembris] 1821" that the son of Pietro Bottesini and his wife Maria, née Spinelli, were born at 1 o'clock in the morning the day before and in their name Ioannes Paul was baptized.

It is undisputed or at least uncontested that Giovanni Bottesini came from a musical family. His father Pietro “was a valued clarinetist and, if only a minor composer of modest pieces of music”. In 1831 the parents gave their son into the care of the clergyman Carlo Cogliati , who taught Giovanni how to play the violin and viola . As the first violinist in the cathedral orchestra of Crema, Cogliati played an important role in the lively musical life of the small northern Italian town, and he helped his protégé to gain their first performance experience within a short time. In addition to studying the two string instruments, Bottesini “had to take part in the church choir as a soprano singer and play the timpani at occasional music performances [in the Teatro Sociale di Crema ]”.

The student years in Milan

In 1835, on the advice of Cogliati, Bottesini's father asked for the not yet 14-year-old to be admitted to the Conservatory in Milan , for which the son of less well-off parents needed a scholarship . In connection with such an allowance, however, only bassoon and double bass study places were available this year . Within a few weeks, Bottesini was preparing for the audition for the class of the renowned double bass professor Luigi Rossi and was admitted. The earliest anecdote from Bottesini's life also reports on this entrance examination, the punch line of which has become a "winged word" that is popular among double bass players to this day . The boy commented on his poor intonation to the jury as follows:

“Sento o Signori, di stonare, ma quando saprò dove posare le dita, allora non stonerò più!”

"I am sorry, gentlemen, for having played so wrongly, but once I know where to put my fingers, it will not happen to me again!"

Bottesini's original hope was that sooner or later, once he had been accepted at the Conservatory, he would still be able to continue his violin studies. However, he did not pursue this plan any further when it soon became apparent that he was making rapid progress as a double bass player and was becoming one of the most successful students of his year. In addition to his main subject studies, the young Giovanni also "eagerly" trained in the subjects of piano , music theory and composition . Bottesini's teachers in these additional subjects were Gaetano Piantanida , Francesco Basili , Pietro Ray and Nicola Vaccai , whose names are hardly known to music historians today, but who were highly regarded as lecturers at the time. Despite this extensive workload, Bottesini managed to complete the six-year compulsory course at the Conservatorio di Milano within four years. The institute also awarded him a prize of 300 francs for his outstanding solo performance.

He used part of this money to buy a double bass that he himself later made famous and that Carlo Antonio Testore had built in 1716. Bottesini himself reported that he discovered the instrument in a storage room of a Milanese puppet theater and then bought it from the estate administrator of the late bassist Fiando for 900 lire .

The story of the acquisition of the Testore bass, which was long thought to be lost after Bottesini's death and could only be identified again in the Netherlands in the middle of the 20th century, has come down to us in various versions, some of which are decorated with great attention to detail. For example, Warnecke mentions an “interested relative” named Rocchetti , without citing a source , who contributed “600 francs” to the acquisition of the instrument. From the rich treasure trove of anecdotes about Bottesini and his instrument, for the sake of curiosity, only the claim that Testore made the bass from the wood of the tree under which Siddharta Gautama found enlightenment in meditation should be mentioned here; Bottesini himself descends in a direct line from Buddha , which is shown by the similarity of the names. Since the spike of the instrument was also turned from a piece of the True Cross , the musician employed porters whose sole job was to ensure that the precious bass was always close to its owner.

Career as a virtuoso

Beginnings in Italy and Austria

Bottesini's rise to internationally acclaimed virtuoso began in 1840 with a triumphant guest performance at the Teatro Comunale in his hometown of Crema. In the same year he gave solo concerts in Trieste , Brescia , the famous La Scala in Milan and finally in Vienna . As usual in the music reporting of the time, Bottesini's career was always depicted in the most dazzling colors by critics. In addition to the taste of the times already described, which valued virtuosos in particular, it goes without saying that Bottesini's instrument - the double bass - was largely unknown to the general public in its soloistic effect. Carniti also points out that the time circumstances for such a career in the years before the start of the Risorgimento were exceptionally favorable because "the development of a lively art policy distracted from the fermenting aspirations for freedom of young Italy". The way to the stages of Central Europe was wide open for young Italian musicians, because “Vienna and Milan had the same opera impresario , and in the imperial city Italian artists set the tone everywhere.” Even the famous and feared Viennese music critic Eduard Hanslick , who for his disapproval “ empty virtuosity "and his aversion to the" Italian taste "was known, Bottesini did not refuse his recognition:

“But there can hardly be a more stubborn material for the Bravour than the contrabass, and also not a more perfect tamer than Bottesini. If someone thinks they have forgotten how to marvel at technical virtuosity, they will learn it again with Bottesini's Production. That an aesthetic impression, which results mainly from astonishment, is not a lasting one, of course, does not first need to be proven. On the other hand, Bottesini deserves the express praise that he also proceeds with taste in the Bravour and disdains those bajazzo-like charlataneries that are so popular with such exceptional instruments. "

After this first and for him very successful concert tour, Bottesini returned to his Italian homeland to gain experience in ensemble playing, i.e. as an orchestral double bass player. Typical of his eagerness to learn is the fact that he did not disdain to initially accept a subordinate position (allegedly at the last desk) in the bass group of the opera orchestra at the Teatro Grande in the relatively provincial Brescia. In the following seasons he received noticeably more prestigious engagements; His last permanent orchestral position was in 1845/46 at the Teatro San Benedetto in Venice . It was there that the bassist also met the composer Giuseppe Verdi, with whom he would have a lifelong friendship.

Toured America and the rest of Europe

In 1846 Bottesini went back to Milan to rehearse the program for an upcoming tour together with his former fellow student, the violinist Luigi Arditi . This concert tour began in Turin in early summer and ended in the small town of Voghera , where a concert agent noticed the two musicians and immediately committed them to an engagement at the Teatro Tacón in Havana .

From then on, Bottesini was more or less constantly on the move for most of the rest of his life. Like hardly any other instrumental musician before him, he made use of the rapid advances in transport , which at that time were beginning to enable fast, safe and comfortable transport for himself and his instrument: The rail network in Europe and North America was expanded in the second half During the 19th century, various shipping companies had started to set up regular service on the transatlantic routes since the end of the 1830s .

The situation in mid-century Havana was in many ways similar to that in Italy: Cuba was the last major colony that Spain had left on the American continent. Here too, emphatic promotion of cultural life served to divert attention from the aspirations for political independence from the mother country. In this environment, the barely 25-year-old “star” found it easy to achieve further successes. He soon began working as a conductor at one of Havana's opera houses, the Teatro Imperial , for which he also wrote his first opera Christoforo Colombo in 1847 . Bottesini conducted the performances of the two-act opera personally. During the break he entered the stage with his double bass and improvised virtuously on the themes of the work, which was enthusiastically received by the audience. The correspondent of the Gazzetta Musicale di Milano reported on September 23, 1847 about the successes of his compatriot in Cuba:

"If the impresario of the Havana Theater wanted a full house, he only had to announce that Bottesini is giving a concert."

From Havana, Bottesini made several guest tours to Mexico and the USA . In 1849 he left the New World for a while to appear in England for a few months, including at such prestigious locations as London's Theater Royal Drury Lane .

As a result, Bottesini began "a continuous, almost five-year uninterrupted journey to and from the new and old world, on which it is almost impossible to follow him". Among other things, the singer Henriette Sontag hired him as Kapellmeister for her guest performance at the Teatro Santa Ana in Mexico City . Unexpectedly unemployed due to the sudden death of Sontag, it was not difficult for the bassist, who had a pronounced organizational talent, to quickly find a new field of activity: the founding of the first conservatory in the Mexican capital was largely due to his initiative. The Italian also took part in the composition competition for the national anthem of Mexico , his contribution was initially awarded a prize, but then rejected again for unclear reasons. The government nevertheless entrusted Bottesini with the first performance of the finally accepted hymn (by Jaime Nunó ) on September 15, 1854.

In the summer of 1855 Bottesini led an international orchestra with Hector Berlioz in Paris , which had been specially put together for the world exhibition , but it was not until 1856 that he returned to Europe permanently. First he settled in Paris again, where he took over the direction of the orchestra at the Théâtre-Italien for almost two years . In the French capital Bottesini's extensive activities as a virtuoso, conductor and composer were followed with great interest: in 1856 alone, the Revue et Gazette Musicale de Paris reported twenty-nine times about him. An appearance specially arranged by his impresario Ullmann took place in the Tuileries Palace before Napoleon III. instead of. The concert was intended as a “gesture of reconciliation” between the French and Italians, since the Italian Felice Orsini had carried out an assassination attempt on the emperor in January 1858. A few months later, however, the invitation to a concert from the Conservatoire represented a special artistic honor .

Successes of this kind made it easy for the bustling agent Ullmann to arrange concerts and long-term engagements in all of Europe's cultural metropolises for his clients. In the 1860s, Bottesini played and conducted in almost all major cities in Germany, Italy and Scandinavia, as well as in Monaco , Lisbon , Madrid and Barcelona . In addition, he gave concerts in St. Petersburg in 1866 at the court of the Russian Tsar Alexander II and in 1873 in Istanbul before Sultan Abdülaziz . He came particularly frequently to fashionable Baden-Baden , which at the time was one of the most popular health resorts of the European upper class and a center of musical life. Even when hostilities broke out at the beginning of the Franco-Prussian War in the summer of 1870, the musician made a guest appearance there and committed the faux pas out of his sympathy for Napoleon III. (who in previous years had supported the national unification efforts in Italy against Austrian foreign rule) to make no secret of it. After the immediate expulsion from Germany - where he performed in the following years only rarely and with noticeably lower public response - to Bottesini was initially short-term settled in London before in May 1871 through the intercession of Verdi's head of the Khedivischen opera in Cairo was appointed .

The conductor and composer

The conductor's profession was a relatively new phenomenon around 1850, the tasks of which were not as highly specialized as they are today. The repertoire generally presented by the opera and concert halls offered far more current works than today, which the composer rehearsed and interpreted together with the musicians involved. Bottesini was no exception in his time, when he seldom worked with a fixed ensemble over a long period of time, but rather wrote new pieces depending on the “order situation” and performed them within the given framework at various locations on three continents.

As a composer, Bottesini, like so many - especially Italian - musicians of his time, represented a type whose artistic conception was primarily shaped by the interests of music theater . “His operas follow the line of development that extends from Gaetano Donizetti to Giuseppe Verdi,” concludes Cesare Casellato , and in a generalized form this statement also applies to the rest of his work. Immediate stage effect is largely given priority over chamber music subtleties. A melody based on the vocal ideal of bel canto and a "sensual" approach to rhythm and agogic , also aimed at attracting the public, play a considerably greater role than in the works of German musicians of this time who were more interested in harmonic innovations. The Italian expressed expressed displeasure at the strongly literary notions of the “ total work of art ”, as represented by Richard Wagner , whose “special meaning remained alien to him”.

His numerous compositions, especially the operas, were in principle commissioned works that were geared to the taste of the day. He could assume that the audience and musicians had a fairly high level of familiarity with the stylistic devices of Italian Romanticism that he preferred to use . As a rule, his works are written for common instrumentation and, based on an underlying handwritten piano reduction , are orchestrated rather sketchily , so that Bottesini, with his own pragmatism, can adapt the details of the execution to the imponderables of the constantly changing and not always familiar singing and singing Instrumental ensembles could adapt. How close the operas he composed are in part to everyday music is most clearly shown by the fact that, in addition to the works themselves, their librettists are now almost completely forgotten. The only exception to this is the opera Ero e Leandro ( premiere Turin 1879, based on the well-known Greek myth of Hero and Leander ), the book of which was written by Verdi's librettist Arrigo Boito . Many music historians see this opera as Bottesini's “best work for the stage”. Another opera, Marion Delorme , which was written during his stay in Palermo (1861/62), is an ambitious work insofar as it is based on a literary model by Victor Hugo ; Here, too, Bottesini worked with a Verdi librettist, namely Antonio Ghislanzoni .

What is rather unusual about Bottesini's way of working, on the other hand, is that he often used his own virtuoso skills on the double bass to familiarize instrumentalists and singers with the musical context or their respective individual voices. The solo intermezzi with which he used to entertain the audience of his operas during the breaks since the success in Havana were one of his often emphasized peculiarities. Bottesini's success as a traveling conductor is primarily due to his musical versatility and flexibility in the face of constantly changing requirements, his familiarity with the music business and public taste of the era and an unusual combination of personal integrity and showmanship .

Bottesini's work as a double bass soloist is thus interwoven in many ways with his work as a conductor and composer. In particular, he continued a tradition already shaped by his predecessors (especially Domenico Dragonetti and Johannes Matthias Sperger ) of composing the pieces for his own solo performance himself. He only interpreted his own compositions on his instrument and did not resort to the common practice of transcribing pieces that had originally been written for other instruments. If he used foreign material (mainly in his fantasies and variations on themes from popular operas), this template only served him as a starting point for independent musical ideas.

Bottesini and Verdi

Verdi and Bottesini had been close friends since their time together in Venice, which is vividly documented by a rather extensive correspondence between the two musicians. Similar to Gioacchino Rossini , with whom the bassist was also friendly, Verdi occasionally expressed his concern about the possible consequences of the lavish lifestyle that Bottesini cultivated:

“Guadagnate molti rubli, teneteli da conto, pensate alla vecchiaia !!!”

"Keep earning lots of rubles, but keep them too, remember your age !!!"

When the end of the virtuoso age became foreseeable, because the public's tastes were noticeably changing and because there were considerable political tensions in Europe around 1870, Verdi therefore considered it his duty of friend to give the easy-going, aging Bohémien Bottesini prospects for the future. At the court of the Egyptian viceroy Ismail Pasha , Verdi had already enjoyed a high reputation since the success of his opera Rigoletto in 1869, so that it was not difficult for the composer to convey to his friend the post of chief conductor that had become vacant at the Khedivian Opera for the 1871 season.

This, as it turned out, the longest lasting engagement in Bottesini's career began with a furious start, as Bottesini could immediately begin rehearsing for Aida . The turmoil of the Franco-Prussian War impaired his work once again, because due to the German siege of the French capital and the subsequent Paris Commune , it was not possible to provide the elaborate costumes and props in time for the transport to Egypt. Contrary to various legends, some of which are rumored to this day, the premiere date of one of the most famous Verdi operas - December 24, 1871 - did not have a special occasion, but is the result of a politically induced delay. Verdi, who was in Genoa during this time , discussed many details of the production in his correspondence with Bottesini. On October 17th the composer wrote (obviously still in anticipation of an imminent premiere):

“Carissimo Bottesini! Ti sono ben grato di avermi dato notizie delle prime prove d'Aida e spero, che me ne darai altre quando sarai in orchestra, e più mi darai anche notizie esatte, sincere, vere, dell'esito della prima sera […]. "

“Dear Bottesini! I am very grateful to you for letting me know about the first rehearsals for “Aida”, and I hope that you will send more when you have rehearsed with the orchestra. I also ask you for accurate, sincere and true news about the success of the first evening. "

How well Bottesini was familiar with the aesthetic objectives of his friend is perhaps best shown by the fact that he succeeded without difficulty in implementing Verdi's very detailed ideas regarding the staging in the case of the Aida to the greatest satisfaction of the composer, even though the two musicians were involved could only communicate with each other by letter.

But Verdi's appreciation was by no means limited to Bottesini's abilities as a conductor. His operas clearly show the influence of the virtuoso friend in the treatment of the double bass parts:

“A closer bond between creative and performing musicians than was the case between Verdi and Bottesini is hardly conceivable. Accordingly, Verdi was able to largely exhaust the possibilities of using the double bass in the orchestra of his time. He wrote the most beautiful double bass solo in opera literature, and in each of his operas as well as in the Requiem , Verdi demonstrated with a number of expert tasks how effectively the double bass can be used. "

The last few years

Bottesini stayed in Cairo until 1878, when the opera house finally had to close due to the long-broken finances of the Egyptian viceroyalty. Although now approaching sixty, he did not let himself be deterred from immediately returning to his lifestyle as a traveling virtuoso and conductor. As this became increasingly difficult in Europe, he crossed the Atlantic again in 1879, this time for an extensive tour of South America. In addition to appearances in the opera house in Buenos Aires and in Montevideo , he also played in Rio de Janeiro (at that time still the capital of Brazil ) for Emperor Dom Pedro II . He stayed again frequently in his native Italy, where he wrote several successful works for the Royal Opera House in Turin.

Once again, Verdi asserted his influence for Bottesini, and so on November 3, 1888, Bottesini was able to take up the post of director of the Regio Conservatorio di Parma . Before the first successes of the new teaching methods he had introduced could be seen, the musician died after a short, serious illness on July 7th of the following year. According to his wishes, he was buried in the municipal cemetery of Parma in the immediate vicinity of the grave of his great idol Paganini.

Honors

Bottesini received numerous honors during his lifetime, especially honorary memberships in many music associations and academies around the world, with the silver medal of the Paris Conservatoire minted especially for him being one of the most exclusive and most valued by him. He also received numerous orders and decorations , including the Crown of Italy , the Turkish Medjedie , San Jago de Portugal , the Portuguese- Vatican Order of Christ and the Spanish orders Isabel la Católica and Carlos III de España . The citizens of Bottesini's hometown Crema financed the erection of a monument in honor of the musician, which was unveiled on October 13, 1901 with great pomp and in front of numerous guests from Italy and abroad.

Works (selection)

The following overview of Bottesini's compositional work must (apart from the operas) remain incomplete because a list of his complete works has not yet been created. In particular, there is hardly any information available about many of his song compositions.

Operas

- Cristoforo Colombo ( Colón en Cuba ). Dramma lirico in one act. Libretto : Ramón de la Palma and Rafael María de Mendive. Premiere 1847 Havana

- L'Assedio di Firenze . Dramma lirico in 3 acts. Libretto: F. Manetta and Carlo Corghi (after Francesco Domenico Guerrazzi). Premiere 1856 (57?) Paris

- Il Diavolo della Notte . Melodramma semiserio in 4 acts. Libretto: Luigi Scalchi. Premiere 1858 Milan

- Marion Delorme . Opera seria in 3 acts. Libretto: Antonio Ghislanzoni . Premiere 1862 Palermo

- Vinciguerra il Bandito . Operetta in one act. Libretto: Eugène Hugot and Paul Renard. Premiere 1870 Monte Carlo

- Alì Babà . Opera comica in 4 acts. Libretto: Emilio Taddei. Premiere 1871 London

- Ero e Leandro . Tragedia lirica in 3 acts. Libretto: Arrigo Boito . Premiere January 11th 1879 Turin (Teatro Regio)

- La Regina del Nepal . Opera seria in 2 acts. Libretto: B. Tommasi da Scaccia. Premiere 1880 Turin

- Nerina . Idillio in one act. Libretto: Duke Proto di Maddaloni. Premiere 1882 Naples

- Azaële o La Figlia dell'Angelo (not listed).

- Cedar (not listed).

- Nerina (not listed).

- Babele (comic opera; not listed).

Works for double bass

Bottesini's oeuvre for double bass comprises several dozen pieces, of which only a few of the most popular are listed here.

- Grande Allegro (Concerto in uno tempo)

-

Concerto No.1 in F sharp minor

Also in various (simplified) transpositions as a study concert for double bass and the like. - Concerto No.2 in B minor

- Introduzione e Variazioni "Il Carnevale di Venezia"

- Introduzione e Gavotta in A major

- Introduzione e Fuga

- Elegia No.1 in re

- Elegia No.2 in mi minore

-

Fantasia “Beatrice di Tenda”

on themes from the opera of the same name by Vincenzo Bellini -

Fantasia “La Sonnambula”

Similar to the previous piece, inspired by the Bellini opera of the same name - Tarantella in A minor

- Bolero in A minor

- polka

- Rêverie

- Concerto di Bravura

- Capriccio di Bravura

-

Nel cor più non mi sento

Variations on an aria by Giovanni Paisiello -

La Fleur , character

piece For the conventional orchestral or G tuning

For two double basses:

-

Gran Duo Concertante

The original version for two double basses is dedicated to Bottesini's teacher Luigi Rossi. The arrangement for double bass and violin by Camillo Sivori is more frequently represented in today's repertoire ; there is another version for double bass and clarinet . - Passione Amorosa

- Tre Grandi Duetti

Religious music

Other genera

Orchestral works

- Sinfonia Caratteristica in D major (Premiere 1863, Paris)

- Fantasia funebre a grande orchestra alla memoria del Colonnello Nullo (Naples Aug. 1863)

- Sinfonia "Graziella" (Paris, undated)

- Notti Arabe (1878)

- Alba sul Bosforo (1881, Turin)

Chamber music

- 11 string quartets , including the string quartet in D major with which Bottesini won the Concorso Basevi in a composition competition in Florence in 1863 .

- Several string quintets , especially the Gran Quintetto for 2 violins, viola, cello and double bass

Vocal music

Apparently Bottesini wrote numerous song compositions, mostly in the conventional line-up for voice with piano accompaniment. Some of these were published in collections of pieces of music by various composers during his lifetime. Some of these works only exist as autographs in the archives of various libraries, especially in Italy, as well as in Austria, France and the USA.

Textbook

- Metodo per il Contrabbasso

Originally published (without the year) by Ricordi in Milan and in a French version by Escudier in Paris in 1872 , Bottesini's textbook for the double bass is now also published in a two-volume, slightly revised edition by the London Yorke Edition . The work differs considerably from most of the other common double bass methods because - in line with Bottesini's virtuoso perspective - it does not focus so much on imparting the skills and knowledge that are important for the orchestral double bass player, but rather on a melodic and wants to prepare rhythmically expressive musical solo performance.

Instrumental style and technique

Throughout his life the Testore bass was Bottesini's preferred instrument, which he had strung with three strings , as was the Italian tradition . In the early years he tuned this to the notes A 1 , D and G based on the example of his predecessor Domenico Dragonetti - just like the tuning of the (mostly four or five-string) bass that is common today in orchestras, whereby the lower strings are omitted. The three-string covering makes the instrument sound more open and clear, which was a decisive criterion for Bottesini, who played predominantly as a soloist. In order to elicit further sonority from his instrument, he preferred an unusually high string position, which, as a very athletically built man with large, powerful hands, was not a particular technical hurdle for him. Already at an early stage in his career, Bottesini started tuning the bass a whole tone higher (i.e. now B 1 , E and A), because in this way he could pull somewhat thinner and therefore more brilliant sounding strings. This so-called “solo mood” has set a precedent and is still preferred by the vast majority of classical virtuosos for performing the double bass solo repertoire.

The English bass player and music publisher Rodney Slatford , who has made a contribution to the contemporary new edition of Bottesini's oeuvre since the 1970s, pointed out, however, that the Italians by no means limited himself to this scordatura , rather he had “his made from silk Strings from half a tone to a fourth are tuned higher than was customary in his time. ” Bottesini used silk as the material for his strings, not least because it was made under the conditions of tropical and subtropical climates in which he often stayed , is a more resilient material than the previously common natural casing. But since it also favors the technical effects he preferred, the strings made in this way prevailed to a certain extent among virtuosos until the first steel strings appeared in the 1920s. However, certain advantages in sound and playability meant that the material popularized by Bottesini was rediscovered at the beginning of the 21st century, and plastics with properties comparable to silk have now been introduced.

Another innovation, which is largely based on Bottesini's role model, is the introduction of a double bass bow , the construction and playing position of which is based on that of the cello . This was suitable for mastering the rapid runs, the rich ornamentation and for the many passages in high and highest registers that characterize Bottesini's double bass playing, far better than the somewhat old-fashioned, short and strongly convex shaped bow, as it was still used by Dragonetti .

Musical effect

Even if Bottesini's rest of the work has largely been forgotten, his compositions for double bass are still extremely popular among players of the instrument. Hardly any significant soloist foregoing at lecture evenings or CD recordings at least one of the technically still highly demanding bravura pieces, which are still regarded as a measure of familiarity with the virtuoso style of Italian romanticism. Some bassists, including above all the Austrian Ludwig Streicher (1920–2003), have even performed or recorded the complete works of Bottesini for this instrument.

The continuing popularity of Bottesini's oeuvre is at least partly due to the fact that "well-known" composers still tend to this day hardly to use the double bass for solo tasks. The composition of demanding and effective performance pieces for the technically unruly instrument requires an intimate knowledge of the possibilities and limitations of fingering , which usually only players of the instrument itself have at their disposal. Among his peers, Bottesini is still by far one of the most productive authors of suitable works, also due to his long career. It is only in the more recent past that François Rabbath , a bassist who succeeds the Italian old master, has aroused a similar level of interest among audiences and experts with his numerous compositions - albeit in a stylistically more modern environment.

Inspired by Bottesini's example, many double bass players pursued a second career as a conductor. Among the best-known are the Russian-born Sergei Alexandrowitsch Kussewizki , the longstanding musical director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra , as well as the Indian Zubin Mehta and the German-Egyptian Nabil Shehata .

literature

- Alberto Basso (Ed.): Dizionario Enciclopedico della Musica e dei Musicisti. Unione Tipografico-Editrice Torinese, Turin 1988, ISBN 88-02-04165-2 .

- Cesare Casellato: Article Giovanni Bottesini. In: Friedrich Blume (Ed.): The music in past and present . Vol. 15, Directmedia, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-89853-460-X , p. 1000 f.

- Luigi Inzaghi et al .: Giovanni Bottesini: Virtuoso del contrabbasso e compositore. Nuove Edizioni, Milan 1989.

- Alberto Pironti: Bottesini, Giovanni. In: Alberto M. Ghisalberti (Ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 13: Borremans – Brancazolo. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 1971.

- Alfred Planyavsky , Herbert Seifert : History of the double bass. Schneider, Tutzing 1984, ISBN 978-3-7952-0426-6 .

- Rodney Slatford: Yorke Complete Bottesini. Three volumes. Yorke, London 1974 (vol. 1 and 2), 1978 (vol. 3).

- Friedrich Warnecke: Ad infinitum. The double bass. Its history and its future. Problems and their solution to improve the playing of the double bass. Supplemented facsimile reprint of the original edition from 1909, edition intervalle, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-938601-00-0 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Giovanni Bottesini in the catalog of the German National Library

- Literature by and about Giovanni Bottesini in the bibliographic database WorldCat

- Sheet music and audio files by Giovanni Bottesini in the International Music Score Library Project

- Bottesini Society website

-

Memorial website with numerous historical images

For the problem of the sometimes deliberately misleading information on this site, see the discussion page for this article. - An analysis of the Testore bass from geigenbauhistorischer view (English)

- An interpretation of Bottesini's Tarantella , soloist: Boguslaw Furtok

- Excerpts from a performance of the Gran Duo Concertante for violin and double bass

Remarks

- ↑ Lt. MGG vol. 15, p. 1000, for uncertainty regarding the date of birth and baptismal name see point 1.1.

- ^ For example, Warnecke, p. 36.

- ^ For example, in an obituary in the London Musical Times of August 1, 1889 and Bottesini, Giovanni . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . 11th edition. tape 4 : Bishārīn - Calgary . London 1910, p. 306 (English, full text [ Wikisource ]).

- ↑ Inzaghi, p. 21.

- ↑ Warnecke, p. 36.

- ↑ Warnecke identifies Cogliati with a family member, namely an uncle of his mother Maria Bottesini, while Planyavsky describes him more generally as a "local musician".

- ↑ a b c Warnecke, p. 37.

- ↑ First in Carniti, p. 15 f., Quoted from Inzaghi, p. 21.

- ↑ Inzaghi, p. 22.

- ↑ Both Warnecke and Planyavsky erroneously write the violin maker's name as “Testori”.

- ↑ According to Planyavsky, p. 274 and the research by Krattenmacher (see web links). From this representation it is not clear how high this amount was converted to the 300 francs gained; Nor is it clear what amount this sum would correspond to in today's currency. Bottesini's account, however, suggests that he acquired an exceptionally valuable (if externally in poor condition) instrument at a low price.

- ↑ The instrument is currently in the private possession of a Japanese collector.

- ↑ A collection of several more of these anecdotes and purrs, which are almost without exception full of incorrect or at least very implausible information, can be found online here .

- ↑ A. Carniti: In memoria di Giovanni Bottesini. Crema 1922, a commemorative publication for the 100th birthday of the musician., Quoted in Planyavsky, p. 273.

- ↑ Planyavsky, p. 273.

- ^ Eduard Hanslick: From the Concert Hall. Reviews and descriptions from 20 years of musical life in Vienna, 1848/68.

- ↑ Although the title of the work is the Italian form of the name Christopher Columbus , the libretto is in Spanish. The Spanish alternative title Colón en Cuba is also often found in literature.

- ↑ The bassist made this solo intermezzo a habit in later years.

- ↑ Planyavsky, p. 274.

- ↑ An outline of the turbulent genesis of the Mexican anthem can be found here , Bottesini's first name Giovanni is always Hispanicized into the corresponding Juan .

- ↑ After a few disappointing and financially lossy guest appearances, Bottesini decided in 1878 not to appear in Germany at all. Warnecke attributes the lack of support from the German audience not only to injured political vanities, but also to "the tremendous upheaval in music brought about by Richard Wagner ".

- ↑ a b Cesare Casellato: Article Giovanni Bottesini In: MGG, Volume 15, p. 1000 f.

- ↑ Warnecke, p. 40.

- ↑ From a letter by Rossini to Bottesini of September 26, 1866.

- ↑ Especially not the opening of the Suez Canal , which had already taken place in 1869.

- ↑ The original Italian text is available online here , the German translation from Planyavsky, p. 275.

- ↑ What is meant is the Otello solo.

- ↑ Planyavsky, p. 280.

- ↑ The catalog raisonné compiled by Inzaghi lists 257 compositions, but mainly takes into account the pieces represented in Italian collections. Since not all of the cataloged sources have survived, it is possible that individual works are listed several times under different titles.

- ↑ During his stay in Florence in 1863, Bottesini was also one of the founding members of the local Società del Quartetto , which felt particularly committed to the cultivation of German music of the Viennese classic .

- ↑ Slatford, Vol. 3, pp. V.

- ↑ Warnecke's communication that Bottesini had "always played on heavily oiled strings" (p. 41) is probably based on an incorrect interpretation of the metallic sheen of the wound silk strings. After all, this shows how unusual the use of this material must have appeared to a German musician of the time: The oiling of gut strings is still common today, but the process makes little sense with silk.

- ↑ Planyavsky, p. 375.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bottesini, Giovanni |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Bottesini, Giovanni Paolo |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian double bass player, conductor and composer |

| BIRTH DATE | December 22, 1821 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Crema , Italy |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 7, 1889 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Parma , Italy |