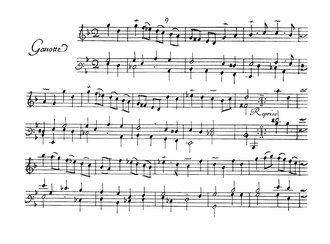

gavotte

The Gavotte (Italian: Gavotta ; English: Gavot ) is a historical society dance in the straight Allabreve- or 2/2-clock. A half-bar start , often in the form of two quarters, is characteristic. It was often part of the baroque suite .

"... Your affect is really a real exultant joy. Your time measurements are straightforward; but not a four-quarter time; but one that consists of two half blows; whether it can be divided into quarters or even eighths. I wanted to wish that this difference would be taken a little better into account ... "

Origin of the word

There are different explanations for the origin of the French word Gavotte : Some experts believe that it comes from the term gavot for the inhabitants of the Pays de Gap in the Dauphiné , mountainous regions near Provence . Another theory is that it comes from the Gaves region , i.e. H. the two rivers Gave de Pau and Gave d'Oloron in southwest France. Still others believe that gavotte means petit galop ("little gallop ").

Musical form

Typical of the Gavotte are:

- A lively, but not too rapid tempo in alla breve - or 2/2 time. Especially in France there are also slower gavottes, e.g. B. in the Pièces de clavecin by Nicolas Lebègue (1677), Jean-Henri d'Anglebert (1689), or François Couperin (1713). The theme of Jean-Philippe Rameau's famous Gavotte with Variations (approx. 1727–1728) is slow and unusually lyrical, more of an aria than a dance. Even Johann Gottfried Walther in his Musicalisches Lexikon (Leipzig 1732) the gavotte as "often fast, but sometimes slow" describes. And Johann Joachim Quantz , in an attempt to give instructions to play the flute traversiere (Berlin, 1752), writes that the gavotte is similar to a Rigaudon , but more moderate in tempo. According to Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1768), the movement of the gavotte is "... usually graceful and graceful ( gracieux ), often cheerful ( gai , allegro), and sometimes tender & slow ( tendre & lent ) ...".

- A hopping and happy, and at the same time somewhat “precious”, cultivated character. The baroque gavotte is a courtly, noble and elegant dance, even the most cheerful examples always retain an aristocratic or ballet-like allure. This bouncy, but classy character is probably also a difference to the somewhat more rustic and, according to Mattheson, rather "flowing" and "leisurely" Bourrée .

“The jumping being is a real property of these gavottes; by no means the current ... "

- Usually a half-bar start , often (but not always) consisting of two short, “hopping” quarters. This brief, bouncing character of the quarters is typical and occurs mostly and at least in the accompaniment during the piece. More rarely there are also full-time gavottes. The half-bar or full-bar beginning is yet another important distinguishing feature to the bourrée , which begins with a simple quarter-opening.

- The gavotte runs regularly without syncope ; Again this in contrast to the Bourrée, whose melody is mostly loosened up by occasional syncopation (often in the last bar of a half-phrase or phrase).

- As a rule, like most other dances, the gavotte consists of two parts, both of which are repeated.

- There are also gavottes in rondo form: The gavotte en rondeau (usually as ABACA). Examples can already be found by Jean-Baptiste Lully , e. B. in the prologues to Atys (1676) or to Armide (1686), and in numerous works by Rameau, for example in his Pièces de clavecin of 1706, or in his Opéra-Ballets Les Indes galantes (1735) and Les Fêtes d'Hébé (1739), and the Tragedy of Zoroastre (1749). There are examples from Germany by Georg Philipp Telemann et al. a. in the overture suite La Bizarre TWV 55: G2. The Gavotte en rondeau by Johann Sebastian Bach in his Partita No. 3 in E major for solo violin, BWV 1006, is also famous . In addition, there are tablatures by anonymous composers who have a gavotte en rondeau in their suites .

- A gavotte can also be coupled with a second gavotte that contrasts with the first, similar to the minuet with trio; after the second gavotte the first is repeated. This phenomenon is called Gavotte I & II and is best known today through the works of Johann Sebastian Bach and Rameau. Especially with Rameau, one of the two gavottes can (but does not have to be) a gavotte en rondeau .

- In (Italian) sonatas or concerts there are occasional pieces that are written in the style of the gavotte, but do not have their typical dance form, e.g. B. by Arcangelo Corelli or Georg Friedrich Handel . Such pieces are then labeled a tempo di Gavotta (see example).

history

16th Century

The gavotte was mentioned by Thoinot Arbeau in his orchésography in 1589: he describes it as the last of a series ( suite ) of Branles doubles; Significantly, he uses the word “Gavotes” only in the plural. It was danced in a row or in a circle "... with small jumps in the manner of the Haut Barrois, ...":

"When the dancers in question have danced a little, one of them comes out (with his lady) and makes some passages in the middle of the dance in front of the others, then he comes to kiss all the other ladies & his lady all the young men, & then they go back to their place, and afterwards the second dancer does the same, & subsequently all the others: But nobody has the privilege to kiss, that belongs only to the boss of the party, and only to those he leads: And finally the lady in question has a cap or a bouquet (= bouquet of flowers, translator's note), and gives it to the dancer who has to pay the musicians and who will be the head of the festival next time ... "

The melody handed down by Thoinot does not begin with a prelude, but is full-time.

17th and 18th centuries

The gavotte became particularly popular from around 1660 at the court of Louis XIV , in the form coined by Jean-Baptiste Lully . He and his successors, such as Michel-Richard Delalande , André Campra , André Cardinal Destouches and Jean-Philippe Rameau, used them extremely often in their ballets and operas. Rameau composed e.g. B. for his tragédie-lyrique Zoroastre (1749/1756) a "Gavotte tendre" (Act I, 3), a "Gavotte en Rondeau I & II" (Act I, 3), a "Gavotte gaye" (Act II, 3), and for the final ballet a “Première Gavotte vive & Gavotte II” (Act V, 8). This example also makes it clear that apart from the various forms discussed above, different characters and tempos were used, as evidenced by the indications “tendre” (tender), “gaye” (happy) and “vive” (lively).

It was not uncommon for the gavotte to be sung on stage, often by a lead singer, and then repeated by the whole choir or by a solo vocal ensemble - all in combination with stage dance. An example in Lully's Atys would be the Gavotte in Act IV, 5, where river gods, deities of springs and streams dance and sing together: La Beauté la plus sévère / prend pitié d'un long tourment / et l'Amant qui persévère / devient un heureux Amant ... (= "Even the strictest beauty has pity on a long torment, and the constant lover becomes a happy lover ...").

Together with the minuet, the gavotte was by far one of the most popular baroque dances, and it is said that they were often coupled with one another in the ballroom. It also found its way into the harpsichord suite as one of the first “additional dances”, or gallanteries . The very first musical examples ever include a gavotte by Jacques Hardel and Nicolas Lebègue in the famous Bauyn manuscript ; Since Louis Couperin (1626–1661), who died prematurely, wrote a double for both , these pieces must have been written before 1661. Hardel's Gavotte was a famous piece that was copied in numerous manuscripts until after 1750, and also existed in versions for other instruments, as a drinking song and a love song; it was also sometimes imitated by other composers, e.g. B. by François Couperin in his Premier Ordre ( Livre premier , 1713).

In harpsichord music since Lebègue ( Livre Premier , 1677), the gavotte, like the minuet, was part of almost every suite (as well as suites for lute or guitar ). In France it was usually at the end of the suite, after the gigue and sometimes after a chaconne, followed only by the final menuet. Examples of this can be found in Lebègue (1677, 1687), Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre (1687), d'Anglebert (1689), Louis Marchand (1702, 1703), and Rameau (1706). It was not until François Couperin ( Livre premier , 1713) that the gavotte was found further forward in the sequence, as he added many character pieces, and from 1716 ( Second Livre ) most of the dances disappeared in favor of the character pieces; but even with him there is still the coupling of Gavotte-Menuet. Rameau's aforementioned Gavotte with 6 variations (approx. 1727–1728) also forms the end of a larger suite (in a / A).

In Germany, the Gavotte found its way into their orchestral and piano suites through the generation of the so-called Lullists ( Johann Sigismund Kusser , Georg Muffat , Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer and others). Composers in the Italian-friendly south often used the Italian form of the name Gavotta , even if the pieces are stylistically entirely French (Muffat, Aufschnaiter). The sequence in the suite corresponded to the loose and free sequence that was also used in France when putting together dances and orchestral pieces from operas and ballets; Telemann , Handel , JS Bach and their contemporaries liked to use it in this form . Bach normally classified the gavotte in his harpsichord and solo suites and partitas between sarabande and gigue , and in his French and English suites, like other composers of the 18th century, liked to use the combination of gavotte I and II (see above).

From the middle of the 18th century, the gavotte gradually went out of fashion, although it was still regularly used as a stage dance in French opera by composers such as Rameau. Even Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart even composed a Gavotte for the ballet music to his opera Idomeneo , K. 367 (1779).

"Gavotte de Vestris"

The Gavotte de Vestris is an almost mythical dance in France, which was first performed on January 25, 1785 in André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry Comédie lyrique Panurge dans l'île des lanternes ("Panurge on the island of lanterns") by the famous Dancer Gaëtan Vestris was danced. The brilliant choreography came from Maximilien Gardel and had little to do with the traditional gavotte.

In 1831 the English dancer Théleur translated the Gavotte de Vestris into a shorthand he had invented and thus saved this dance from being completely forgotten. During the 19th century it was introduced at balls and in the repertoire of military music and in France it became the mandatory rehearsal for every prévôt de danse .

Late 19th and 20th centuries

Composers of the late 19th and 20th centuries occasionally wrote “gavottes” that had little or nothing to do with baroque dance, especially the polka-like pieces by Johann Strauss Sohn ( Gavotte der Königin , op. 391) and Carl Michael Ziehrer ( Golden Youth, op. 523); but also for Richard Strauss (Suite in B flat major op. 4).

Closer to the character of the baroque or rococo original are the gavotte in Edvard Grieg's Holberg Suite op. 40, or the (sung) gavotte from Ambroise Thomas ' opera Mignon . Even Jules Massenet settled by time and action of his opera Manon to a few bars "Gavotte" in a scene for coloratura soprano inspired, known as "Gavotte of Manon."

Gavotten also exist in Gilbert and Sullivan: In the second act of The Gondoliers and in the finale of Act I of Ruddigore . Sergei Prokofiev uses a “gavotte” instead of a minuet in his Classical Symphony .

The so-called “glow worm idyll” from the opera Lysistrata (1902) by Paul Lincke is also known as Gavotte Pavlova because it was a favorite piece of the famous dancer Anna Pawlowa , who invented her own choreography and danced on her tours.

Gavotte in Breton music

As a folk dance and folk music genre, the gavotte is still alive today in Brittany , where numerous gavottes ( Gavotte de l'Aven , Dañs Fisel , Gavotte des Montagnes , Kost ar c'hoad ) are an integral part of dance festivals such as the Fest-noz . It has a two-bar structure in common with the baroque gavotte. The rhythm is mostly a syncopated 4/4 time, but 9/8 and 5/8 time should also occur.

The Gavotte des Montagnes and the Dañs Fisel are i. d. Usually performed in a three-part suite in which the first fast part ( tone simpl ) is followed by a slow step dance ( Tamm-kreiz ), which in turn is followed by a fast closing part ( tone doubl ). This has the same rhythm as the tone simpl , but the second part of the two-part melody is here often lengthened by a few characteristic bars.

swell

literature

- Thoinot Arbeau: Orchésographie ... Jehan des Preyz, Langres 1589 / réedition 1596 (privilege of November 22, 1588). = Orchésography. Reprint of the 1588 edition. Olms, Hildesheim 1989, ISBN 3-487-06697-1 . Digital copies : http://imslp.org/wiki/Orchésographie (Arbeau, Thoinot) , [1]

- Johann Mattheson: The Gavotta ... (§ 87-89) and The Bourrée (§ 90-92). In: The perfect Capellmeister. 1739. Ed. Margarete Reimann. Bärenreiter, Kassel et al., Pp. 225–226.

- Meredith Ellis Little: Tempo di gavotta. In: Deane Root (Ed.): Grove Music Online.

- Meredith Ellis Little, Matthew Werley: Gavotte. In: Deane Root (Ed.): Grove Music Online. (updated & rev .: 3 September 2014).

- Bruce Gustafson, foreword to: Hardel - The Collected Works ( The Art of the keyboard 1 ). The Broud Trust, New York 1991.

- Text accompanying the CD collection (translation by Gery Bramall): Fête du Ballet - A Compendium of Ballet Rarities. (10 CDs; here CD No. 2 “Homage to Pavlova”). Dir. Richard Bonynge, various orchestras. Decca, 2001.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Gavotte. In: Dictionnaire de musique. Paris 1768, p. 230. (See also on IMSLP: http://imslp.org/wiki/Dictionnaire_de_musique_(Rousseau%2C_Jean-Jacques)) .

- Percy Scholes. Gavotte. In: The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 1970.

- Philippe Quinault, libretto for Lully's Atys . In the booklet accompanying the CD: Atys, de M. de Lully. Les Arts florissants, William Christie. Harmonia Mundi France, 1987.

grades

- Jean-Henry d'Anglebert: Pièces de Clavecin - Édition de 1689. Facsimile. Ed. De J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1999.

- Manuscript Bauyn,… , troisième part: Pièces de Clavecin de divers auteurs. Facsimile. Edited by Bertrand Porot. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 2006.

- François Couperin: Pièces de Clavecin. 4 vols. Ed. Jos. Gát. Schott, Mainz et al. 1970–1971.

- Nicolas-Antoine Lebègue, Pièces de Clavecin, Premier Livre, 1677. Facsimile. Edited by J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1995.

- Nicolas-Antoine Lebègue: Le Second Livre de Clavessin, 1687. Facsimile. Edited by J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay.

- Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre: Les Pièces de Clavecin, Premier Livre , 1687. Facsimile. Edited by J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1997.

- Louis Marchand, Pièces de Clavecin, Livre Premier (1702) and Livre Second (1703). Complete edition. Facsimile. Edited by J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 2003.

- Jean-Philippe Rameau, Pièces de Clavecin (Complete Edition). Ed. ER Jacobi. Bärenreiter, Kasel et al. 1972.

Web links

- YouTube film 1: Gavotte du Roy (baroque dance)

- YouTube film 2: Gavotte from Atys by Jean-Baptiste Lully

- YouTube film 3: Gavotte de Vestris , with Jean-Marie Belmont

- YouTube film 3: Gavotte de l'Aven (Breton folk dance)

Remarks

- ↑ Gavottes with a simple quarter as a prelude are very rare, but then the boundaries begin to blur if the performer does not try to emphasize the bouncing, 'precious' character.

- ↑ This piece is also referred to as Air pour la suite de Flore (= "Air for the entourage of Flora ") (see also the YouTube film 2 under the web links).

- ↑ The text passage in Arbeau is somewhat blurred, it is not entirely clear whether the entire suite of Branles doubles mentioned was called “Gavottes”.

- ↑ The tempo for “tendre” is quieter than the other two, and remember that franz. “Gaye” corresponds to the Italian word “allegro”, which actually also means “happy”, not “fast”, as one is usually taught in German (in music!).

- ↑ It must be emphasized that this order is only typical for Bach and cannot be generalized (see above).

- ↑ Although the music itself is quite typical.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Johann Mattheson, "Die Gavotta ..." (§ 87-89), in: The perfect Capellmeister. Bärenreiter, Kassel et al. P. 225.

- ↑ Percy Scholes: Gavotte. In: The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 1970.

- ↑ z. B. the gavotte of the first suite in d, in: Nicolas-Antoine Lebègue: Pièces de Clavecin, Premier Livre, 1677. Facsimile,… ,: Édition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1995, p. 13.

- ^ D'Anglebert was an employee of Lully, in whose Comédie-ballets and Tragédies he played continuo ; d'Anglebert expressly writes the expression lentement ("slow") in several of his gavottes for harpsichord . Two of these pieces are old tunes ( Airs anciens ), which he set for the harpsichord and provided them with his flowery decorations; At least one of these old wise men ( Ou estes-vous allé? ) is probably not an old gavotte, but an old folk song. S. Jean-Henry d'Anglebert: Pièces de Clavecin - Édition de 1689. Facsimile. Edited by J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1999, p. 23 (G), pp. 55-56.

- ^ At F. Couperin z. B. the otherwise very typical gavotte in G minor of the Second Order . (François Couperin: Pièces de Clavecin. Schott, Mainz 1970–1971, Vol. 1, p. 15.)

- ↑ ... Le mouvement de la 'Gavotte' est ordinairement gracieux, souvent gai, quelquefois aussi tendre & lent. See: Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Gavotte. In: Dictionnaire de musique. Paris 1768, p. 230.See also on IMSLP: http://imslp.org/wiki/Dictionnaire_de_musique_(Rousseau%2C_Jean-Jacques) , viewed August 12, 2017.

- ↑ The Bourrée is occupied by Mattheson u. a. with the properties: "... something filled, stuffed, thick, strong, important, and yet soft or delicate that is more adept at pushing, sliding or sliding than lifting, hopping or jumping". One paragraph further he says about a certain bourrée called la Mariée ("the bride"): "He is truly not better suited to any kind of body shape than to a subordinate one." See: Johann Mattheson: The Bourrée. (§ 90-92) In: The perfect Capellmeister. Bärenreiter, Kassel et al. Pp. 225–226.

- ↑ Louis de Cahusac also wrote in the Encyclopédie of 1751 (vol. 2, p. 372) that the bourrée was "... little used because this dance did not seem noble enough for the Théatre de l'Opéra."

- ↑ Johann Mattheson: Die Gavotta .... In: The perfect Capellmeister. Bärenreiter, Kassel et al. § 88, p. 225. (Mattheson here uses the term “running fences” to refer to Italian violinists who apparently misinterpreted the gavotte and added many barrels.)

- ^ Les Indes Galantes , 3rd act ( 3me Entrée ).

- ↑ Zoroastre , Act 1, Scene 3.

- ↑ and also in Suite TWV 55: D18.

- ↑ See for example Adalbert Quadt : Guitar music of the 16th – 18th centuries. Century. According to tablature ed. by Adalbert Quadt. Volume 1-4. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1970 ff., Volume 2: based on tablatures for Colascione, Mandora and Angelica, 3rd edition ibid 1972, pp. 23, 38 and 40–43.

- ↑ There are examples from Rameau u. a. in Les Indes galantes (1735), Zoroastre (1749/1756), Daphnis et Aeglé (1753), Les Boreades .

- ↑ An example is in Les Indes galantes , 2me Entrée, where Gavotte 2 is a rondeau.

- ↑ See also: Meredith Ellis Little: Tempo di gavotta. In: Deane Root (Ed.): Grove Music Online. (last accessed: January 3, 2016).

- ↑ Gavottes, cest un recueil & ramazun de plusieurs branles doubles que les joueurs ont choisy entre aultres, & en ont composé une suytte que vous pourrez sçavoir deulx & de voz compagnons, a laquelle suytte ils ont donné ce nom de Gavottes par mesure binaire, avec petits saults, en façon de hault barrois ,… (underlined text passage corresponds to the short quotation in the main text). See: Thoinot Arbeau: Orchésographie ... Jehan des Preyz, Langres 1589 / réedition 1596 (privilege of November 22, 1588). = Orchésography. Reprint of the 1588 edition. Olms, Hildesheim 1989, ISBN 3-487-06697-1 .

- ↑ Quand lesdits danceurs ont quelque peu dancé, l'un d'iceulx (avec sa Damoiselle) s'escarte a part, & fait quelques passages au meillieu de la dance au conspect de tous les aultres, puis il vient baiser toutes les aultres Damoiselles , & sa Damoiselle tous les jeusnes hommes, & puis se remettent en leur renc, ce fait, le second danceur en fait aultant, & consequemment tous les aultres: Aulcuns donnent ceste prerogative de baiser, seullement a celuy qui est le chef de la Festivals , & a celle qu'il mene: Et en fin ladicte Damoiselle ayant un chapelet ou bouquet, le presente a celuy des danceurs qui doibt payer les joueurs, & estre le chef de la Festivals a la prochaine assemblee, ...

- ↑ See also: Johann Mattheson: Die Gavotta ... (§ 87-89.) In: The perfect Capellmeister. Bärenreiter, Kassel et al. P. 225.

- ↑ In the libretto there is the entry chantants, & dansants ensemble (“singing and dancing together”). See: Philippe Quinault: Libretto for Lully's Atys . In the booklet accompanying the CD: Atys, de M. de Lully. Les Arts florissants, William Christie. Harmonia Mundi France, 1987, pp. 144-145.

- ↑ Percy Scholes: Gavotte. In: The Oxford Companion to Music. University Press, Oxford / New York 1970.

- ↑ For example, the previously mentioned Gavotte in Lullys Atys is directly followed by a menuet.

- ↑ Manuscript Bauyn,… , troisième part: Pièces de Clavecin de divers auteurs. Facsimile. Edited by Bertrand Porot. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 2006, pp. 75-76 (Hardel-L. Couperin) and p. 79 (Lebègue-L. Couperin).

- ↑ Louis Couperin's double for Lebègue is strangely enough in a completely different time scheme than the original piece (phrases of 7 bars each for Couperin, instead of 4 bars each for Lebègue). Lebègue published the same gavotte in C in 1677 with its own double. See: Nicolas-Antoine Lebègue: Pièces de Clavecin, Premier Livre, 1677. Facsimile. Edited by J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1995, pp. 77-78.

- ↑ Bruce Gustafson, foreword to: Hardel - The Collected Works ( The Art of the keyboard 1 ). The Broud Trust, New York 1991, pp. Xii, also pp. 36-38.

- ↑ With Couperin, the ascending dotted line can be seen immediately at the beginning, even if the piece is in G minor. François Couperin: Pièces de Clavecin. Schott, Mainz 1970–1971, Vol. 1, pp. 15-16. Lebègue also wrote another “copy”, in the same key as Hardel (A minor). Nicolas-Antoine Lebègue: Pièces de Clavecin, Second Livre. 1687. D'Anglebert plays at the beginning of his Gavotte in G (1689) with an inversion of the Hardel melody. Jean-Henry d'Anglebert: Pièces de Clavecin - Édition de 1689. Facsimile. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1999, p. 23.

- ↑ Cf. for example Camille de Tallard , edited by Hubert Zanoskar (ed.): Gitarrenspiel old masters. Original music from the 16th and 17th centuries. Volume 1. B. Schott's Sons, Mainz 1955 (= Edition Schott. Volume 4620), p. 19 f.

- ↑ 1677: Gavotte Menuet at the end: Suites in G minor and C major. Gavotte at the end (no menuet): Suites in D and in F. The suite in D minor has a canaris at the end after Gavotte and Menuet. (Without gavotte: suite in a). 1687: Gavotte Menuet at the end: Suite in A minor. Gavotte I & II at the end: Suite in G minor. Gavotte-Petitte Chaconne at the end: Suite in G major (Without Gavotte: Suites in A and F). See: Nicolas-Antoine Lebègue: Pièces de Clavecin, Premier Livre, 1677. Facsimile. Edited by J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1995. And: Nicolas-Antoine Lebègue: Le Second Livre de Clavessin, 1687. Facsimile. Edited by J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay.

- ↑ In the suite in A minor (the other three suites are without gavotte). Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre: Les Pièces de Clavecin, Premier Livre. 1687. Facsimile. Edited by J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1997, pp. 40-58 (Gavotte-Menuet on pp. 57-58).

- ↑ The suites in G and D close with Gavotte-Menuet (each is followed by an overture by Lully, which logically can be seen as the beginning of another series of movements), in G minor there is none between Passacaille and the overture by Lully More original compositions, but four pieces, the first of which is a minuet by Lully, then two airs anciens, which he declares as gavotten, and finally a vaudeville in the character of a minuet. The suite in D major has neither. Jean-Henry d'Anglebert: Pièces de Clavecin - Édition de 1689. Facsimile. Edited by J. Saint-Arroman. Édition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1999, pp. 23–24 (G major), pp. 83–84 (D minor).

- ↑ The two books each present a suite that both end with Gavotte-Menuet, in the case of 1703 it is Menuet I and II. Louis Marchand: Pièces de Clavecin, Livre Premier (1702) and Livre Second (1703). Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 2003.

- ^ Jean-Philippe Rameau: Pièces de Clavecin. (Complete edition) ed. by ER Jacobi. Bärenreiter, Kassel et al. 1972, pp. 1-13 (Gavotte on 12-13).

- ↑ In the 2me and 3me order. François Couperin: Pièces de Clavecin , vol. 1. Ed. Jos. Gát. Schott, Mainz et al. 1970–1971, p. 45f and p. 82f.

- ↑ Muffat in Armonico Tributo (1682) and in Exquisitoris Harmoniae Instrumentalis Gravi-Iucundae Selestus Primus (1701), and Aufschnaiter in the serenades of his Concors discordia collection , Nuremberg 1695.

- ^ Text accompanying the CD collection (translation by Gery Bramall): Fête du Ballet - A Compendium of Ballet Rarities. (10 CDs; here CD No. 2 Homage to Pavlova ). Dir. Richard Bonynge, various orchestras. Decca, 2001, p. 29.

- ↑ Meredith Ellis Little, Matthew Werley: Gavotte. In: Deane Root (Ed.): Grove Music Online. (updated & rev .: 3 September 2014).