Jean-Henri d'Anglebert

Jean-Henri d'Anglebert (born around April 1, 1629 in Bar-le-Duc , Département Meuse , † April 23, 1691 in Paris ) was a French composer , harpsichordist and organist .

Life

Jean-Henri d'Anglebert's father, Claude Henry dit Anglebert, was a shoemaker in Bar-le-Duc. Nothing is known about Jean-Henri's early musical training, nor is there any information about how he came to Paris. It is believed that he was a student of Jacques Champion de Chambonnières . The fact that one of his most beautiful pieces is the tombeau for Chambonnières suggests friendship and great respect. A musical manuscript containing entries in d'Anglebert's handwriting and those by Louis Couperin and possibly also by Chambonnières suggests a close collaboration with the leading members of the French harpsichord school of the 1650s.

Jean-Henri d'Anglebert's first trace in Paris is the marriage contract with Magdelaine Champagne (October 11, 1659), sister-in-law of the goldsmith and organist François Roberday . In it he is described as a citizen of Paris. Besides Roberday, one of the witnesses was Joseph de la Barre, organist of the royal chapel. D'Anglebert and his wife had ten children together who were born between 1660 and 1683, all of whom, with one or two exceptions, reached adulthood and outlived him by many years. Numerous members of the court were among the godparents of his children. a. Jean-Baptiste Lully and Alexandre Bontemps, the personal valet of Louis XIV .

D'Anglebert's first professional job was probably that of an organist with the Jacobins of Rue Saint-Honoré, when they negotiated with the organ builder Etienne Enocq (January 26, 1660) about a new organ.

In August 1660 he succeeded Henry Du Mont as organist at Philippe d'Orléans , the brother of Louis XIV. He held this position until at least 1668. On October 23, 1662, d'Anglebert von Chambonnières bought his court office of joueur d'espinette for 2000 livres; Chambonnières, however, remained officially the holder of the office and kept a pension of 1,800 livres a year until his death in 1672. On August 25, 1668, d'Anglebert signed another agreement with Chambonnières for his office as royal porte-épinette (" Harpsichord carrier "), to cover the cost of transporting the harpsichord" ... where it is necessary for His Majesty's service ... ". It was only after Chambonnières' death that d'Anglebert officially took over the position of harpsichordist at the court of Louis XIV. Two years later (1674) he officially handed over this position to his eldest son Jean-Baptiste Henry (1661–1735), who at the time was only 13 years old.

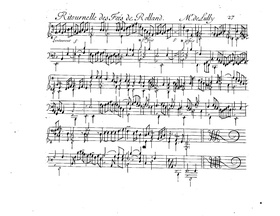

In Versailles , d'Anglebert worked with Jean-Baptiste Lully , from whose operas and ballets he arranged numerous overtures , airs and dances for harpsichord. He published these together with four of his own suites and a few vaudevilles in his Pièces de clavecin …, Livre Premier (Paris 1689). The collection also includes a Kyrie and five short joints (on the same subject) for organ, and also the most extensive table of ornaments that has ever been published (29 different trills , mordents , suspensions , double beats , arpeggios etc.). In the foreword to his Pièces de clavecin , the composer announced a second volume with pieces in different keys, but this project was prevented by his death on April 23, 1691.

He was buried in Saint-Roch the next day, leaving five minor children behind.

At his death, d'Anglebert owned four instruments: two harpsichords with three registers (presumably 8 ', 8', 4 '), one of which was simple and the other was "... painted inside and out ...". In addition, a smaller espinette with two registers, "... painted in the Chinese way ...". The last instrument was "... a small harpsichord from Flanders by Ruckers ...". The latter was single-manual and had two registers, probably the typical 8'4 'disposition of the Ruckers instruments.

Music and meaning

D'Anglebert is admired by some as the most important French clavecinist before François Couperin (1668–1733); However, it should not be concealed that the extreme abundance of ornamentation in his works does not please all (modern) minds, and that his music is not particularly suitable for beginners for today's harpsichord beginners who are not yet familiar with French baroque music .

In addition to the extremely carefully prepared print of the Pièces de clavecin from 1689 with suites in the keys of G major, G minor, D minor and D major, there are some manuscripts with individual works by d'Anglebert. The most important of these is the Rés 89ter manuscript in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris . In addition to some of the published pieces from 1689, this contains other works by d'Anglebert in the keys of C major and A minor, as well as d'Anglebert's versions and doubles of works by Chambonnières, Louis Couperin and Étienne Richards; In addition, numerous harpsichord transcriptions of works by French lutenists such as Ennemond Gaultier “Le Vieux”, Mézangeau , Pinel, a sarabande by Marin Marais , as well as pieces from Jean-Baptiste Lully's Tragédie lyriques Isis , Thésée and Xerxès - presumably all by d'Anglebert . A comparison of Ms Rés 89ter with the print from 1689 also helps to clear up small ambiguities or misunderstandings with regard to some decorations, since in the manuscript some decorations are written out and appear directly in the musical context.

D'Anglebert's harpsichord works are a further development of the elegant music of Chambonnières and Louis Couperin in particular. As the numerous surviving transcriptions from his hand suggest, he developed his personal style with the conscious inclusion of elements of French lute music, to which there were already references in the harpsichord music of his predecessors. Another influence that should not be underestimated, especially in melodic and harmonic terms, is Jean-Baptiste Lully, with whom there was a longstanding musical cooperation and who was also the godfather of his eldest son.

From these various elements, d'Anglebert created a harpsichord style that can no longer be surpassed in terms of roaring sonority, glittering splendor and unprecedented ornamentation. In addition, there is a great and sophisticated elegance and softness of melody and voice leading and in his best works also great expressiveness. D'Anglebert also used the resources of the lower octave of the harpsichord particularly effectively (up to GG). One could say that in d'Anglebert's music the fairytale pomp and wealth of the French court and Versailles , and the reign of the Sun King Louis XIV, are reflected at their absolute, triumphant zenith.

In addition to the introductory prelude non mésuré, D'Anglebert used the typical dance forms of his time such as allemande , courante , sarabande and gigue in his suites . As with Chambonnières, Louis Couperin, Jacques Hardel , Lebègue (1676) and others. a. there is a particular preference for the courante: two suites (G major, G minor) from 1689 bring three courants one after the other, the other two two courants, some with doubles. These traditional basic dances are supplemented by the modern gallantries such as gavotte and menuet , which Lully also extensively used in his stage works , and by chaconne and passacaille . D'Anglebert is probably the last composer who composed gaillarden , which he always placed between gigue and chaconne or gavotte. Stylistically they follow Chambonnières' Gaillarden, but are even slower, of a solemn, measured and poetic nature (in 3/2) with particularly refined, flowery ornamentation. His Tombeau de Mr. de Chambonnieres is formally such a Gaillarde, but at a particularly slow pace (“ fort lentement ”).

A question that has not been clearly resolved is whether his transcriptions by Lully and the small, often delightful “Vaudevilles” were combined with his own pieces to form suites, or stand on their own. These transcriptions, which have been completely neglected or even rejected for a long time, have been played again for some time, but are usually grouped into separate suites. The sequence of a suite in C in the above-mentioned manuscript Rés 89ter , however, mixes d'Anglebert's own works with those of his colleagues, and the doubles he composed, as well as transcriptions. The contemporary performance practice was probably more colorful and less strict than today's.

D'Anglebert's Preludes non mesurés , published in 1689, are of particular importance for the understanding and performance practice of this genre (apart from its beauty and expressiveness). Before him, Nicolas Lebègue (1631–1702) tried in his Pièces de clavecin of 1676, and the much younger Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre (1665–1729) in her Premier Livre of 1687, their preludes a little clearer and understandable for laypeople to be written down as the works handed down by Louis Couperin. Nonetheless, d'Anglebert deserves special credit and recognition for the way in which he wrote his Preludes in print from 1689. A comparison with some of the handwritten preludes in Ms Rés 89ter , which are written there in white notation like those by Louis Couperin, is also interesting and illuminating .

At the end of his Pièces de clavecin from 1689, d'Anglebert also gives some brief but valuable tips on playing the figured bass (“Principes de l'Accompagnement”).

grades

- Pieces de clavessin. Performers' Facsimiles, New York 2002 (reprint of the Amsterdam 1704 edition).

- Jean-Henry d'Anglebert, Pièces de clavecin - Édition de 1689. Facsimile, publ. sous la dir. de J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1999.

- Manuscript Rés. 89 ter, Pieces de clavecin: D'Anglebert - Chambonnières - Louis Couperin - Transcriptions de pièces pour luth , Facsimile, publ. sous la dir. de J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1999. (= second volume of the D'Anglebert complete edition of the Édition Fuzeau).

- Manuscrit Bauyn, première partie: Pièces de clavecin de Jacques Champion de Chambonnières, deuxième part: Pièces de clavecin de Louis Couperin, troisième partie: Pièces de clavecin de divers auteurs, Facsimile, prés. by Bertrand Porot. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 2006.

- Jacques Champion de Chambonnières, Les Pièces de clavessin, Vol. I & II , Facsimile of the 1670 Paris Edition. Broude Brothers, New York 1967.

- Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre, Les Pièces de clavecin, Premier Livre, Paris (sd = 1687), Facsimile, publ. sous la dir. de J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1997.

- Nicolas-Antoine Lebègue, Pièces de clavecin, Premier Livre, 1677 , Facsimile, publ. sous la dir. de J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1995.

literature

- Beverly Scheibert: Jean-Henri d'Anglebert and the seventeenth century clavecin school. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Ind. 1986, ISBN 0-253-38823-6

- Bruce Gustafson: d'Anglebert (family). In: Ludwig Finscher (Hrsg.): The music in past and present . Second edition, personal section, volume 1 (Aagard - Baez). Bärenreiter / Metzler, Kassel et al. 1999, ISBN 3-7618-1111-X ( online edition , subscription required for full access)

- Philippe Lescat: biography and bibliography. In: Jean-Henry d'Anglebert: Pièces de clavecin - Édition de 1689 , Facsimile, publ. sous la dir. de J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1999, pp. 5–10 (French) and pp. 37–42 (German).

- Grant O'Brian: Ruckers - A harpsichord and virginal building tradition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 1990.

Web links

- Sheet music and audio files by Jean-Henri d'Anglebert in the International Music Score Library Project

Individual evidence

- ↑ Information from: Philippe Lescat: Biography and Bibliography. In: Jean-Henry d'Anglebert: Pièces de clavecin - Édition de 1689 , Facsimile,…, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 1999, pp. 5-7 (French) and 37-39 (German).

- ^ Philippe Lescat: Biography and Bibliography. In: Jean-Henry d'Anglebert: Pièces de clavecin - Édition de 1689. Facsimile,…, Édition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1999, p. 6 (French) and p. 38 (German).

- ^ Jean-Henry d'Anglebert: Pièces de clavecin - Édition de 1689. Facsimile, publ. sous la dir. de J. Saint-Arroman. Edition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1999, p. 38.

- ^ Philippe Lescat: Biography and Bibliography. In: Jean-Henry d'Anglebert: Pièces de clavecin - Édition de 1689. Facsimile,…, Édition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1999, p. 6 (French) and p. 38 (German).

- ↑ According to the composer himself in his foreword to the Pièces de clavecin . He meant popular melodies and pieces that he added because of their popularity and to use every space between larger works (!).

- ^ Philippe Lescat: Biography and Bibliography. In: Jean-Henry d'Anglebert: Pièces de clavecin - Édition de 1689 , Facsimile,…, Édition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1999, p. 7 (French) and p. 39 (German).

- ↑ This espinette was probably a one-manual harpsichord, as spinets with 2 registers were very rare (but not entirely uncommon!). At that time, the French term espinette could be understood as an umbrella term for various types of keel instruments, such as: B. in the standing expression joueur d'espinette for the office of court harpsichordist, as it had been exercised before d'Anglebert by Chambonnières and his ancestors. By the way, it is noticeable that Chambonnières' estate also mentioned a espinette with chinoiserie and a ceiling painting by Parnassus. It is conceivable that it was the same instrument. See also: Bruce Gustafson: Champion, 1st Thomas, 2nd Jacques (II), sieur de la Chapelle, 3rd Chambonnières, Jacques Champion. In: Ludwig Finscher (Hrsg.): The music in past and present . Second edition, personal section, volume 4 (Camarella - Couture). Bärenreiter / Metzler, Kassel et al. 2000, ISBN 3-7618-1114-4 , Sp. 698-706

- ↑ Information from the inventory drawn up after his death. See: Jean-Henry d'Anglebert, Pièces de clavecin - Édition de 1689. Facsimile,…, Édition JM Fuzeau, Courlay 1999, p. 7 (French original text) and p. 39 (German).

- ↑ For the typical Ruckers disposition, see the chapter The standard type of harpsichord. In: Grant O'Brian: Ruckers - A harpsichord and virginal building tradition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 1990, pp. 40ff.

- ↑ Manuscript Rés. 89 ter, Pieces de clavecin: D'Anglebert - Chambonnières - Louis Couperin - Transcriptions de pièces pour luth , Facsimile, publ. sous la dir. de J. Saint-Arroman, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 1999. (= second volume of the D'Anglebert complete edition of the Édition Fuseau).

- ↑ This is supported by the characteristic use of ornaments and d'Anglebert's typical, small changes to the melody or voice guidance. According to Bruce Gustafson, there is a certain degree of probability that d'Anglebert himself was the scribe of Ms Rés 89ter . See: Jean-Henry d'Anglebert, Pièces de clavecin - Édition de 1689 , Facsimile, publ. sous la dir. de J. Saint-Arroman, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 1999, p. 7 (French) and p. 44 (German).

- ^ Nicolas-Antoine Lebègue, Pièces de clavecin, Premier Livre, 1677 , Facsimile, publ. sous la dir. de J. Saint-Arroman, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 1995.

- ↑ Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre, Les Pièces de clavecin, Premier Livre, Paris (sd = 1687), Facsimile, publ. sous la dir. de J. Saint-Arroman, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 1997.

- ↑ Manuscript Bauyn,…, deuxième part: Pièces de clavecin de Louis Couperin, … , Facsimile, prés. by Bertrand Porot, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 2006.

- ↑ Manuscript Rés. 89 ter, Pieces de clavecin: D'Anglebert - Chambonnières - Louis Couperin - Transcriptions de pièces pour luth , Facsimile, publ. sous la dir. de J. Saint-Arroman, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 1999.

- ^ Jean-Henry d'Anglebert, Pièces de clavecin - Édition de 1689 , Facsimile,…, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 1999, pp. 123–128.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Anglebert, Jean-Henri d ' |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French composer, harpsichordist and organist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around April 1, 1629 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bar-le-Duc , Meuse department, France |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 23, 1691 |

| Place of death | Paris |