Chaconne

The Chaconne (French: [ʃaˈkɔn] , more rarely also chacone ; from Spanish: chacona ; Italian: Ciacona or ciaccona [tʃaˈkona], etc.; English: chacony [ˈtʃ ɛ k ə n i ]) is a dance and a musical variation -Three-beat form that had its heyday in the late 16th to 18th centuries. Typical for the Chaconne is an ostinato bass with a constantly repeating harmony scheme lasting four to eight bars. It is closely related to the Passacaglia .

Chaconnas (also Chaconnes ) in straight two or four time are very rare ( Pachelbel : Ciacona in C major; François Couperin : “La Favorite” ( 3me Ordre , 1713)).

history

According to Curt Sachs , the Chaconne is of Hispanic American origin and used to have a sensual, wild and unrestrained character. Such pieces were not only danced but also sung. A piece by Juan Arañez, the " Chacona A la vida bona ", also called " Un sarao de la chacona " (1624, Rome, Robletti), is relatively well known. The chaconne as an instrumental form can be found as early as 1554 in vihuela works by Miguel de Fuenllana and in guitar and lute pieces from the 17th century such as those of Robert de Visée or anonymous authors.

The early baroque Italian ciacona

It was first included in art music in Italy from the early 17th century. The Italian ciacona of this time is based on a very specific basso ostinato - corresponding to other dance basses and ostinati such as the Passamezzo , the Romanesca , or the famous Folia . This early Italian ciacona is in major and clearly has a cheerful character; the tones of the ostinato are in C major: c'-gaefgc, but are rhythmized in a special way, with stresses against the grain (see the bass model in the music example).

There are get set technically elaborate and often virtuoso examples: The first and most most elaborate include Girolamo Frescobaldi Cento partite sopra passacaglia (= "One hundred games over passacaglia"), in the third edition of his Libro Primo di toccata ... 1637. Within this passacaglia - There are also three variations of Ciacconas whose ostinato (in C major) is: 3 ||: C - g | a ef g: || . Frescobaldi treats this ostinato as freely as possible, plays around with it and changes it; in parts it can almost or completely disappear and also appear in different voices. He also composed similar little ciacconas as an appendage to a balletto or a corrente.

Claudio Monteverdi's duet “Zefiro torna” (9th Madrigal Book (1651, posth.), SV 251) is a particularly ingenious arrangement of the Ciaccona Ostinatos . The “ Pastorale sulla ciaccona” (for two voices) by Orazio Giaccio (Naples 1645) and “Es Gott auf” by Heinrich Schütz ( Symphoniae sacrae II, SWV 356, final part) are probably inspired by this . Examples from instrumental music are Antonio Bertali's sweeping and virtuoso “ Chiacona ” (sic!) In C major for solo violin and B. c. , and the four-part Ciaccona for harpsichord by Bernardo Storace (in Selva ... , Venice 1664), also in C major . Bertali modifies the ostinato slightly (he leaves out the e), and in the meantime modulates in all possible keys, whereby the bass is shifted in each case; z. Sometimes he makes extensive use of chromatics . Storace adds two middle parts, which are in F and B major, and there used a triol regard 9/8 in contrast to the main metrum 3/1 in the first and last part; he also modifies the bass in the form of lively figurations. Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber very likely got to know the Italian ostinato model through Bertali (who worked at the imperial court in Vienna), and used it in his famous serenade with the night watchman in 1673 , precisely at the climax, the night watchman's appearance in the fourth movement , a ciacona played pizzicato . Here the ostinato model is extended by an alternating note h at the beginning and is supplemented and interrupted by the sung melody of the night watchman (a bass voice): "Hear you people and let me tell you ...". Biber used the Italian Ciacona bass again as the final movement of Partia III of his Harmonia artificioso-ariosa collection (Salzburg 1696), with a canon in unison between the two virtuoso solo violins.

France and England

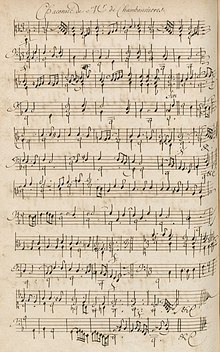

From around 1640 or 1650 the Chaconne came to France, where it was probably introduced into harpsichord music by Louis Couperin , in the special form of Chaconne en rondeau : This is not based on the Ostinato form, but is a rondo with one always recurring refrain A and any number of couplets (interludes), i.e. ABACADA etc., the refrain can have a certain resemblance to the Italian Ciacona , or it is worked on its own bass, e.g. B. a rising line or a falling tetrachord , the couplets are usually completely free and modulate in other keys. These types of chaconnas are also composed not only in major but also in minor keys, e.g. B. Louis Couperin already has two chaconnas in D minor, one each in G minor and one in C minor (and five more in major). The same applies to later clavecinists such as Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre , Louis Marchand , François Couperin and others. a. Sometimes parallel major and minor were mixed in one piece. E. Jacquet de la Guerre did this as early as 1687 in her first suite in D minor in her Chaconne " L'Inconstante " ("The Inconsistent"), where the refrain is (noticeably) in D major and the five couplets are not only change to the parallel D minor, but modulate from there to A or F; the fifth time the refrain is moved to D minor, after the following fifth couplet the piece ends with the original sixth refrain in D major. She also published a similar Chaconne in D major and D minor in the later book of 1707, also as the end of a suite in D minor.

Jean-Baptiste Lully composed large-scale and artistic chaconnas for orchestra in ostinato form for his ballets and operas . Partly sections in contrasting orchestration, often with soloists. He often used it as a festive, shiny climax towards the end (i.e. shortly before the end), e.g. B. in the Comédie-Ballet Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (1670), or in the Tragédies Phaëton (1683) or Acis et Galatée (1686). Like the early Italian Ciaccona, the three chaconnas mentioned are in major keys, and the Chaconne in Phaëton has a very similar bass, which is only slightly modified and simplified to a descending line. Partly slightly chromated ; stylistically, however, they are completely French. The Parisian musicologist Raphaëlle Legrand describes this as follows: A chaconne often sets in at the moment of the hero's triumph, slows the planned progress of the tragedy to an agitated stability and maintains the audience's vigilant attention despite sometimes 900 bars lasting more than 20 minutes - systematics is missing and the ostinato bass is constantly varied in its endless loop. The fact that the Chaconne forces an almost hypnotic effect in which time seems to stand still, with the ostinato bass circling at the same time, is what makes it typically baroque with this contradiction.

The Chaconne was also developed in a similar way by Lully's successors Campra , Rameau and others. a. used in their stage works. Rameau's Chaconnen are among the highlights of the genre, due to their refined orchestration and the many imaginative ideas that the composer processes in them. Examples can be found u. a. in Hippolyte et Aricie (1733), Castor et Pollux (1737), Dardanus (1739), Platée (1745). In terms of form, too, he is sometimes very free with the traditional models. An example of this is z. B. the Chaconne in Platée , which is played as a festival for the impatient title character, and as a comic effect is supposed to create the impression that it will never stop - it actually has no real ending, but is simply abruptly interrupted (by the appearance the personified madness La Folie ), and then goes straight to the action. Another example of Rameau's formal freedom is the Final Chaconne from Les Indes Galantes (1735), which begins in a minor key and after a very short time changes to major with surprising trumpet fanfares; even after that, not only are the motley sections mixed in minor and major, but also features from the ostinato chaconne with those from the chaconne en rondeau - but the piece is neither a real rondeau nor a continuous ostinato.

Even after Rameau, the Chaconne was still used in French opera, e.g. B. by Mozart contemporaries such as Grétry ( La Caravane du Caire , 1783).

Lully's Chaconnen also had an impact on French harpsichord music, where in the 18th century there were also works with an ostinato structure, e.g. B. in Dandrieu (e.g. "La Figurée" in the 2nd Livre , 1728, and "La Naturèle" in the 3rd Livre , 1734). The style of the Chaconne in F major by Jacques Duphly (3rd Livre , 1756) is inspired by Rameau's operatic chaconnas.

Henry Purcell also used the Chaconne in his stage works in England in the spirit of Lully . He was one of the greatest masters of ostinato forms and chose his own bass models. Well-known examples can be found in King Arthur (1691) or in The Fairy Queen (1692). Purcell's Chaconne in G minor for 3 violins and B. c is also very famous. (Z 730), a particularly artistic piece, where he uses an ostinato that seems at least rhythmically based on the early Italian dance bass. In the typically English tradition (after William Lawes ), the harmony is often very daring, enriched with dissonances, and Purcell also modulates a few times in surprising directions.

Germany

German composers of the 17th and 18th centuries wrote impressive and artistic solo works in the form of a chaconne or ciacona. Most of these pieces are influenced by the virtuoso Italian style and formally correspond to the ostinato-chaconne, but the original early baroque ostinato model from Italy is usually exchanged for completely freely chosen basses. Here too, some pieces are in a minor key.

Beaver chose u. a. for his Rosary Sonatas No. 4 in D minor (“Presentation in the Temple”) and No. 14 in D major (“Assumption of Mary”) the form of the Ciacona, but here he uses his own bass models. The model of Sonata No. 4 is actually untypical for a chaconne because it consists of 4 + 4 bars that are repeated each time - it almost corresponds to an aria with variations.

Amazingly, like the Passacaglia, the Ciacona was also adopted in organ music; it is then really no longer to be understood as a dance, but as a pure work of variation. Most famous are Buxtehude's organ chaconnas in E minor (BuxWV 160) and in C minor (BuxWV 159), as well as the splendid Final Ciacona of the Prelude BuxWV 137 in C major, which has a peculiarly lively bass that is virtuoso for the pedal Has. Pachelbel , Georg Böhm , Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer , Johann Krieger and Christoph Graupner also write chaconnas for organ or harpsichord . An example of the use of the Chaconne in sacred music is not found in Matthias Weckmann's sacred concert Weine, it has overcome . In the concluding Amen (No. 5) there are three very artistically interwoven male voices above the orchestral and organ ostinato, which is held in a very cheerful dance.

Georg Friedrich Handel composed several small and three large chaconnas for harpsichord. The best known is in G major (HWV 435) and was published in 1733. The theme has eight bars and begins in the style of an Italian adagio, followed by 21 variations in a style borrowed from Corelli and Vivaldi; the contrasting middle section (var. 9-16) is in G minor. In the same collection from 1733 there is also an even larger and technically more demanding Chaconne with 62 variations, also in G major (HWV 442). A third Chaconne in C major is probably a brilliant early work. It is handed down both as the finale of the suite in C major HWV 443 with 27 variations, but also as a single piece with 50 variations - the theme in the first four bars is reminiscent of Purcell's Chaconne from The Fairy Queen .

The most famous of all chaconnas is that from Partita No. 2 in D minor for solo violin (BWV 1004) by Johann Sebastian Bach , a great virtuoso piece with numerous double, triple and quadruple fingerings. After 132 bars it changes into a radiant D major, but for the last variations (48 bars) it returns to the starting key of D minor (part A: 132; part B: 75; part C: 48). There are also some transcriptions : Johannes Brahms transferred them to piano for the left hand solo and wanted to recreate the limitations of the violin; Ferruccio Busoni left behind a romanticizing and virtuoso arrangement that is tailored to the tonal possibilities of the piano and the audience expectations of a late romantic piano virtuoso. Siegfried Behrend , among others, arranged for guitar .

From around 1700 the Chaconne also appears increasingly in German orchestral music. It is then more inspired by Lully, or a typically German stylistic mixture of French and Italian elements. There are examples in orchestral suites by Johann Joseph Fux , Telemann a . a., or in Handel's ballet music for Almira (1705) or for Terpsicore (prologue to the second version of Il pastor fido , 1734).

Relatively late examples of festive ballet chaconnas from the classical period were written by Gluck for his opera Orfeo ed Euridice (1762), and Mozart for his ballet music for Idomeneo, Rè di Creta KV 367 (1781). Mozart's piece is a Chaconne en rondeau in D major, and a roaring, colorful and expressive climax of the whole opera, which is considered one of his masterpieces anyway. It marks a worthy end to the actual epoch of the Chaconne.

Chaconne or Passacaglia?

“The biggest among the dance melodies is probably XVII. The Ciacona, Chaconne, with her brother, or her sister, the passaglio, or passecaille. "

Much has been written or speculated about the difference between Ciaccona and Passacaglia, or Chaconne and Passacaille, in musicology of the 20th and 21st centuries. As in the above formulation by Mattheson, there are “sister genres” that are sometimes difficult to distinguish from one another, at least on paper, and are often treated in the same breath by the composers themselves and by contemporary music theorists of the Baroque era.

Well-known examples are Frescobaldi's Cento Partite sopra Passacagli (“Hundred Games on Passacagli”) from 1637, where he designates three sections as Ciaccona ; by Louis Couperin there is a piece in G minor with the confusing title "Chaconne ou Passacaille" (= "Chaconne or Passacaille"). The definition by Johann Walther 1732 is also significant:

“Passacaglia or Passaglio [ital.], Passacaille [gall.], Is actually a Chaconne. The whole difference is that ordinairement is slower than the Chaconne, the melody more dull-hearted (more tender) and the expression not so lively; and that is precisely why the passecailles are almost always set in the modis minoribus, ie in notes that have a soft third. "

Accordingly, in contrast to the Chaconne, the Passacaglia is characterized by a softer, sweeter or more melancholy character, and therefore appears more often than this (but not always!) In minor. This key tendency is also confirmed by Mattheson in his Perfect Kapellmeister 1739 (although he contradicts the tempo).

The difference in character and that the Chaconne should be played a little faster than the Passacaille (or vice versa) is also confirmed by all French theorists, such as Freillon-Poncein 1700, L'Affilard (1702 and 1705), Brossard 1703, Pajot 1732, Montéclair 1736, d'Alembert / Rameau 1759 and Rousseau 1768. There are also pieces by François Couperin and Jean-Philippe Rameau that are called mouvement de passacaille or mouvement de chaconne , which are to be played in motion or at the pace of a passacaille or chaconne . An example of the former is F. Couperin's harpsichord piece L'Amphibie (24th Ordre, Livre IV , 1730), which he calls mouvement de Passacaille . Examples from Rameau's operas are an Air. Mouvement de chaconne vive in Acanthe et Céphise (1751), an Air de Ballet (Mouvement de Chaconne) in Platée (1745), or a Rondeau. Mouvement de chaconne in Zoroastre ( 1749/1756 ).

Walther's definition of major or minor seems to be confirmed by the observation that the early Baroque Italian Ciaccona was actually a happy ostinato in major, in contrast to the more melancholy “Passacagli”. This applies, for example, to Storace, who left only one arrangement of the Ciaccona in C, but four Passacagli: one in A minor, one in C minor, one that modulates from F minor via B minor to B major, and one that goes from D major through A and E to B minor.

What has been said applies particularly to Frescobaldi's above-mentioned Cento Partite sopra Passacagli , where two of the three Ciaccona sections are in F major and C major, only the third Ciaccona is in A minor and D minor (although the question is whether he still thought in church modes at all). A perhaps even more important differentiator in Frescobaldi already observed Silbiger. It consists in the fact that the ostinato in the Ciaccona parts moves significantly faster than in the Passacagli: the latter consist of an ostinato of "four three-measure groups" each, while the ostinato of the Ciaccona has only "two three-measure groups" . This means that there are more harmonic changes per measure in the Ciaccona parts, similar to the basic model of the Italian Ciaccona presented above. This alone makes Frescobaldi's Passacagli parts appear calmer and more melancholy (but also through melodic tricks).

Lully's magnificent chaconnas from Le Bourgeois gentilhomme , Phaeton and Acis et Galatée are also in major, while he z. B. wrote his Passacailles in Persée (1682) and Armide (1686) in minor; Similarly, D'Anglebert, who was a collaborator of Lully, differentiates in his harpsichord book (1689) between two chaconnas in G and D major, and two passecailles in G minor. The three great chaconnas of Handel in G major or C major also speak for Walther's definition. Fischer also ended his Musicalisches Blumenbüschlein collection (1695) with a Chaconne in G major - the only Passacaille in the collection is in A minor (in Suite III); Fischer ends his musical Parnassus (1738) with a large Passacaglia in D minor - of the three chaconnas in the collection, the longest is in F major (in Euterpe ), but the two remaining, unusually short chaconnas are in A minor (Melpomene ) and E minor (Erato) . In the tendency with two Passacaglia in minor and two Chaconnas in major, however, Fischer agrees with Walther, even if the question arises as to why he did not at least call the clearly melancholy piece of the Melpomene Suite “Passacaglia”.

From a modern perspective, a few chaconnas in minor cause particular confusion, namely the most famous of them all today: Bach's Chaconne in D minor for solo violin. There are also Buxtehude's well-known organ ciaconas in E minor (BuxWV 160) and C minor (BuxWV 159), and Pachelbel's “Ciacona” in F minor, which, due to its impressive beauty, is more in the foreground than the others in D and C.

Although the use of minor does not necessarily and always have to mean a melancholy character or slow tempo (as in the Passacaglia), and although tempo and interpretation play a role, it remains to be stated that the genre boundaries are blurred and that there are some in the repertoire There are noticeable exceptions that stand out due to their particular awareness and had a special influence on newer developments.

How Mozart felt the two genres can be seen in his ballet music for Idomeneo (KV 367), which contains both a festive chaconne in D major and a sweeter and more graceful passacaille in E flat major.

19th and 20th centuries

The Chaconne as a stage dance went out of fashion towards the end of the 18th century, and as a variant form even earlier. In the late 19th century, the form of variation was picked up again very sporadically, inspired primarily by Bach's violin chaconne. The Chaconne in G minor for violin and basso continuo, which the violin virtuoso Ferdinand David ascribed to the Italian Baroque composer Tomaso Antonio Vitali around 1860 , probably did not date from the Baroque period, according to Hermann Keller, but was composed in the 19th century. The extensive harmonic modulations, but also z. B. the conspicuously “romantic” octave parallels and other details in the violin part.

The operatic-grandiose and tragic colored finale of . Symphony No. 4, Op E Minor 98th of Johannes Brahms is sometimes called Chaconne: The eight-bar theme (with slight changes) of Bach - Cantata " After you, Lord, I long " BWV 150 taken. It is introduced by the winds at the beginning and then varied in over 30 artfully orchestrated variations, with the theme mostly being present in the bass instruments. However, musicologists disagree as to whether it can be called a Chaconne or a Passacaglia - or whether it should simply be viewed neutrally as an ostinato.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, the form of the Chaconne was and is again used relatively often by modern composers; the models are mostly likely to be the famous pieces by Bach, Buxtehude and Purcell mentioned several times - so only a very specific, relatively small excerpt from it the historical production of the baroque. Important Chaconne compositions from the 20th century are by Carl Nielsen , Franz Schmidt , Emil Bohnke and Hans Werner Henze (final movement from the concerto for double bass and orchestra).

Web links

Youtube films:

- Juan Arañes: Chacona a la vida bona , 1624 , as seen on August 5, 2017

- Baroque dance 1: Chaconne from Phaeton (1683) by Lully; danced by Carlos Fittante (chamber music version) , as seen on August 2, 2017

- Baroque dance 2: Chaconne from Purcell's The Fairy Queen (1692); danced by the company "Ris et Danceries", 1989 Aix-en-Provence, seen on August 3rd 2017

- Henry Purcell's Chacony in g minor for 3 violins and B. c. (Z 730), played by the Purcell Quartet , as seen on August 4, 2017

- D. Buxtehude: Ciacona in E minor for organ, BuxWV 160 (D minor erroneously appears in the title of the video!). Played by Ulrik Spang-Hanssen , as seen on August 5, 2017

swell

literature

- Willi Apel , History of Organ and Piano Music up to 1700 . Edited and epilogue by Siegbert Rampe, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2004 (originally 1967).

- Jan van Biezen: Het tempo van de Franse barokdansen (The tempo of French Baroque dances). In: Tempo in de achttiende eeuw , red. K. Vellekoop, Utrecht 1984 (Stimu), pp. 7-25, pp. 37-59. (Dutch). An English summary of the article on: http://www.janvanbiezen.nl/frenchbarok.html (as of August 11, 2017).

- Gerald Drebes: Schütz, Monteverdi and the "perfection of music" - "God stands up" from the "Symphoniae sacrae" II (1647) . In: Schütz yearbook. Vol. 14 , 1992.

- Victor Gavenda: Booklet text on CD: Rameau - Suites from Platée & Dardanus , Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, Nicholas McGegan, published by: conifer classics, 1998, p. 17.

- Hermann Keller: The Chaconne in G minor by - Vitali? . In: New magazine for music. Vol. 125 , No. 4, April 1964, ISSN 0170-8791.

- Raphaëlle Legrand: Chaconnes et passacailles dansées dans l'opéra français: des airs de mouvement . In: Hervé Lacombe (ed.): Le mouvement en musique à l'époque baroque , Editions Serpenoise, Metz 1996, pp. 157–170.

- Johann Mattheson: XVII. The Ciacona, Chaconne, with her brother, or her sister, the passaglio, or passecaille. In: The perfect Kapellmeister 1739 , facsimile, ed. Margarete Reimann, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1954 / 5th edition 1991, p. 233.

- David Moroney: Booklet text for CD: Biber - The Mystery Sonatas , John Holloway (violin), Davitt Moroney (harpsichord and organ), Tragicomedia (continuo). published by: Virgin classics / veritas, 1990.

- Konrad Ragossnig: Manual of the guitar and lute. Schott, Mainz 1978, ISBN 3-7957-2329-9 .

- Lucy Robinson (translated by Stephanie Wollny): Booklet for CD: Biber - Sacro-profanum , The Purcell Quartet a. a., Richard Wistreich (bass), published by: Chaconne, 1997 (2 CDs).

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Passacaille . In: Dictionnaire de musique, Paris 1768, p. 372.See also on IMSLP: Rousseau: Dictionnaire de musique, 1768, accessed August 12, 2017.

- Thomas Schmitt: Passacaglio is actually a Chaconne. To distinguish between two musical composition principles , In: Frankfurter Zeitschrift für Musikwissenschaft. Vol. 13, 2010, ISSN 1438-857X , pp. 1–18 , (PDF; 364 kB).

- Walter Siegmund Schultze: Georg Friedrich Handel . VEB German publishing house for music Leipzig 1980.

- Erich Schwandt: L'Affilard on the French Court Dances . In: The Musical Quarterly. Volume LX, Issue 3, 1 July 1974, pp. 389-400, doi: 10.1093 / mq / LX.3.389

- Alexander Silbiger: Chaconne. In: The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians , ed. Stanley Sadie & J. Tyrrell, London: Macmillan, 2001.

grades

- Jean-Henry d'Anglebert, Pièces de Clavecin - Édition de 1689 , Facsimile, publ. sous la dir. de J. Saint-Arroman, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 1999.

- Manuscript Bauyn,…, deuxième part: Pièces de Clavecin de Louis Couperin, … , Facsimile, prés. by Bertrand Porot, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 2006.

- François Couperin, Pièces de Clavecin , 4 vols., Ed. by Jos. Gát, Mainz et al .: Schott, 1970–1971.

- Jean-François Dandrieu, Pièces de Clavecin (1724, 1728, 1734), ed. by P. Aubert & B. François-Sappey, Paris: Editions Musicales de la Schola Cantorum, 1973.

- Jacques Duphly: Troisième Livre de Pièces de Clavecin , 1756. New York: Performer's Facsimiles 25367 (n.d.),

- Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer, Complete Works for Keyboard Instrument , ed. v. Ernst von Werra, Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, (originally 1901).

- Girolamo Frescobaldi, Toccate d'Intavolatura di Cimbalo ..., Libro Primo , Rome 1615 and 1637. New edition by Pierre Pidoux, Kassel: Bärenreiter (originally 1948).

- Georg Friedrich Handel, Piano Works I - Various Suites, Part a (Wiener Urtext Edition) , Vienna / Mainz: Schott / Universal Edition, 1991.

- George Frideric Handel: Keyboard Works for solo instrument, (from the Deutsche Handel Gesellschaft Edition) , ed. by Friedrich Chrysander. New York: Dover Publication, 1982.

- Johann Pachelbel: Hexachordum Apollinis 1699 , ed. v. HJ Moser and Tr. Fedtke, Kassel: Bärenreiter 1958/1986.

- Bernardo Storace, Selva di Varie compositioni d'Intavolatura per Cimbalo ed Organo , Venezia 1664. New edition (facsimile) by: Studio per Editioni scelte (SPES), Firenze, 1982.

Recordings (CDs)

- Bertali's “Chiacona a violino solo”, on the CD: Johann Heinrich Schmelzer - Unarum fidium , John Holloway (baroque violin), Aloysia Assenbaum, Lars Ulrik Mortensen (continuo), from the label: ECM Recors 1999.

- Biber's "Serenade with the Night Watchman", on the CD: Biber - Sacro-profanum , The Purcell Quartet a. a., Richard Wistreich (bass), published by: Chaconne, 1997 (2 CDs).

- Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber: Harmonia artificioso-ariosa , M. Kraemer, P. Valetti, The Rare Fruits Council, published by Audivis Astrée (1995/1996) (CD).

- Cristofaro Caresana - Christmas Cantata "Per la Nascita del Verbo" (Tesori di Napoli Vol. 1) , Cappella de 'Turchini, Antonio Florio, published by: Opus 111, 2000.

- Johann Joseph Fux: Concentus musico-instrumentalis I, Armonico Tributo Austria, Lorenz Duftschmid, published by: Arcana, 1998.

- Georg Friedrich Händel: Chaconne (including) from Almira (1705), on the CD : Overtures for the Hamburg Opera (Music or the Hamburg Opera) , Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, published by: harmonia mundi France, 2004.

- Lully - Armide , G. Laurens, H. Crook, V. Gens, Collegium Vocale, Chapelle Royale, Ph. Herreweghe, published by: harmonia mundi France, 1992 (2 CDs).

- Monteverdi's “Zefiro torna” with Jean-Paul Fouchécourt and Mark Padmore (tenor), on the CD: Claudio Monteverdi - Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda , Les Arts florissants, William Christie, on the label: harmonia mundi France 901426, 1993.

- Mozart - The Overtures (Complete Edition) , Basler Sinfonieorchester, Moshe Atzmon, published by: Ariola-eurodisc, 1974 (3 LPs).

- Purcell - King Arthur , The Deller Choir, The King's Musick, Alfred Deller, published by: harmonia mundi France 1979 (2 LPs).

- Henry Purcell: The Fairy Queen , Les Arts Florissants, William Christie, published by: harmonia mundi France, 1989 (2 CDs).

- Jean-Philippe Rameau: Castor & Pollux , Les Arts florissants, William Christie, published by: harmonia mundi France, 1993 (3 CDs).

- Jean-Philippe Rameau: orchestral suite from “Hippolyte et Aricie” , La Petite Bande, Sigiswald Kuijken, published by: deutsche harmonia mundi 1979 (LP).

- Jean-Philippe Rameau: Les Indes galantes , Les Arts florissants, William Christie, published by: harmonia mundi France, 1991 (3 CDs).

- Rameau - Suites from Platée & Dardanus , Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, Nicholas McGegan, appear in: conifer classics, 1998.

Individual evidence

- ↑ The piece is in even C-measure, changes to var. 16-22 in 3/4, and in other variations in 6/4 and in triplet meters like 6/8 and 12/8. The triplet meters are basically to be understood as a special form of an even measure. See: Johann Pachelbel: Hexachordum Apollinis 1699 , ed. v. HJ Moser and Tr. Fedtke, Kassel: Bärenreiter 1958/1986, pp. 36–42.

- ↑ To emphasize the particularity, "La Favorite" also has the subtitle "Chaconne à deus tem (p) s", François Couperin, Pièces de Clavecin , vol. 1, ed. by Jos. Gát, Mainz et al .: Schott, 1970-1971, pp. 93-96.

- ^ In: Libro segundo de tonos y villancicos , Rome: Giovanni Battista Robletti, 1624.

- ^ Konrad Ragossnig : Handbook of the guitar and lute. Schott, Mainz 1978, ISBN 3-7957-2329-9 , p. 106.

- ^ Adalbert Quadt : Guitar music from the 16th to 18th centuries Century. According to tablature ed. by Adalbert Quadt. Volume 1-4. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1970 ff .; 2nd edition ibid 1975–1984, Volume 3, pp. 21 and 57.

- ↑ The Passamezzo was particularly popular in the 16th century, there are significant variations on keyboard instruments by Andrea Gabrieli , Valente , Byrd , Philips , Picchi , Scheidt , but also by Storace (1664). See: Willi Apel , History of Organ and Piano Music until 1700 , ..., Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2004 (originally 1967), p. 257 (on Passamezzo and Romanesca), p. 264–270 ("The Passamezzo Variations") .

- ↑ The Romanesca was used by various Italian composers as the basic scheme for variations, only in the keyboard music of Antonio Valente, Scipione Stella, Ascanio Mayone , Ercole Pasquini , Frescobaldi, Storace; and also before by lutenists such as Narváez , Mudarra and Valderrábano (under the name: (Romanesca) Guardame las vacas . Willi Apel , History of Organ and Piano Music until 1700 , edited and afterword by Siegbert Rampe, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2004 ( originally 1967), p. 270 (A. Valente), p. 415 (Ercole Pasquini), p. 419 (Stella), & 428 (Mayone et al.), p. 450-454 (Frescobaldi), p. 450 (lutenists , Narvaez et al.), P. 664 (Storace).

- ^ Forms of folia were u. a. Used in keyboard music by Frescobaldi, Storace, Bernardo Pasquini , A. Scarlatti , D'Anglebert, F. Couperin. The most famous folias are from Corelli and Vivaldi . See also: Willi Apel , History of Organ and Piano Music up to 1700 , ed. and afterword by Siegbert Rampe, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2004 (originally 1967), p. 450 & 454 (Frescobaldi), p. 664 f (Storace), p. 681 (Pasquini).

- ↑ Girolamo Frescobaldi, Toccate d'Intavolatura di Cimbalo…, Libro Primo , Rome 1615 and 1637. New edition by Pierre Pidoux, Kassel: Bärenreiter, pp. 77–85. The three Ciacconas are on: pp. 80–81 (F major, at the end to C), p. 82 (C major, at the end to a), and p. 83 (A minor - D minor).

- ↑ Girolamo Frescobaldi, Toccate d'Intavolatura di Cimbalo ..., Libro Primo , Rome 1615 and 1637. New edition by Pierre Pidoux, Kassel: Bärenreiter, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Monteverdi's “Zefiro torna”, sung by Jean-Paul Fouchécourt and Mark Padmore (tenor), on the CD: Claudio Monteverdi - Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda , Les Arts florissants, William Christie, on the label: harmonia mundi France 901426, 1993 .

- ↑ See the CD: Cristofaro Caresana - Christmas Cantata “Per la Nascita del Verbo” (Tesori di Napoli Vol. 1) , Cappella de 'Turchini, Antonio Florio, published in: Opus 111, 2000.

- ↑ Gerald Drebes: Schütz, Monteverdi and the "Perfection of Music" - "God stands up" from the "Symphoniae sacrae" II (1647). In: Schütz yearbook . Vol. 14, 1992, pp. 25–55, online ( memento of the original from March 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ Bertalis Chiacona a violino solo can be heard on the CD: Johann Heinrich Schmelzer - Unarum fidium , John Holloway (baroque violin), Aloysia Assenbaum, Lars Ulrik Mortensen (continuo), on the label: ECM Records 1999.

- ↑ Bernardo Storace, Selva di Varie compositioni d'Intavolatura per Cimbalo ed Organo , Venezia 1664. New edition (facsimile) by: Studio per Editioni scelte (SPES), Firenze, 1982, pp. 70-77.

- ↑ Bernardo Storace, Selva di Varie compositioni… 1664. New edition: ... Firenze, 1982, pp. 70–77.

- ↑ Lucy Robinson (translated by Stephanie Wollny): Booklet text for the CD: Biber - Sacro-profanum , The Purcell Quartet a. a., Richard Wistreich (bass), published by: Chaconne, 1997 (2 CDs), p. 5 and p. 16-17.

- ^ Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber: Harmonia artificioso ariosa , M. Kraemer, P. Valetti, The Rare Fruits Council, published by Audivis Astrée (1995/1996), p. 2 (content in the booklet) & item no. 17 “Ciacona canon in unisono ”(on the CD).

- ↑ Louis Couperin has received a particularly large number of chaconnas, which can be considered the earliest examples because of his early death in 1661. A piece in the Bauyn manuscript is dated 1658. See: Manuscrit Bauyn,…, deuxième Partie: Pièces de Clavecin de Louis Couperin, … , Facsimile,…, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 2006, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Manuscript Bauyn, ..., deuxième part: Pièces de Clavecin de Louis Couperin, ... , Facsimile, prés. par Bertrand Porot, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 2006, p. 55 (C minor), p. 72, p. 74 (D minor), p. 147 (G minor).

- ↑ Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre: Les Pièces de Clavecin, Premier Livre , 1687,…, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 1997. pp. 18-21 ( L'Inconstante , D major / D minor).

- ↑ In this piece the 3rd and 5th couplets begin directly in D minor, the others modulate more gently from D major to A minor. Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre: Pièces de Clavecin…, 1707.…, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 2000. pp. 17–20 (D major / D minor). A third Chaconne from 1687 is in A minor, in: Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre: Les Pièces de Clavecin, Premier Livre , 1687,…, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 1997. pp. 18-21, pp. 34-36 (A minor).

- ↑ This can be seen very clearly in d'Anglebert's version for harpsichord. See: Jean-Henry d'Anglebert, Pièces de Clavecin - Édition de 1689 , Facsimile, publ. sous la dir. de J. Saint-Arroman, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 1999, pp. 29-33.

- ↑ Raphaëlle Legrand: Chaconnes et passacailles […] . In: Hervé Lacombe (ed.): Le mouvement en musique […]. Metz 1996, p. 169 f.

- ↑ See the recordings: Jean-Philippe Rameau: Castor & Pollux , Les Arts florissants, William Christie, published by: harmonia mundi France, 1993 (3 CDs). Jean-Philippe Rameau: orchestral suite from “Hippolyte et Aricie” , La Petite Bande, Sigiswald Kuijken, published by: deutsche harmonia mundi 1979 (LP). Jean-Philippe Rameau: Les Indes galantes , Les Arts florissants, William Christie, published by: harmonia mundi France, 1991 (3 CDs). Rameau - Suites from Platée & Dardanus , Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, Nicholas McGegan, appear in: conifer classics, 1998.

- ↑ Victor Gavenda: Booklet text on CD: Rameau - Suites from Platée & Dardanus , Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, Nicholas McGegan, appear in: conifer classics, 1998, p. 17.

- ↑ Jean-Philippe Rameau: Les Indes galantes , Les Arts florissants, William Christie, published by: harmonia mundi France, 1991 (3 CDs), the Chaconne is the last piece on CD No. 3.

- ↑ Jean-François Dandrieu, Pièces de Clavecin (1724, 1728, 1734),…, Paris: Editions Musicales de la Schola Cantorum, 1973, pp. 87–91 ( La Figurée. Chacone , 2nd Livre, 1st Suite), and pp. 134–137 ("La Naturèle", 3rd livre, 1st suite)

- ^ Jacques Duphly: Troisième Livre de Pièces de Clavecin , 1756. New York: Performer's Facsimiles 25367 (n.d.), pp. 10-14.

- ↑ The Chaconne is always the last piece in the score. See the recordings: 1. Purcell - King Arthur , The Deller Choir, The King's Musick, Alfred Deller, published by: harmonia mundi France 1979 (2 LPs). 2. Henry Purcell: The Fairy Queen , Les Arts Florissants, William Christie, published by: harmonia mundi France, 1989 (2 CDs).

- ↑ David Moroney: Booklet text on CD: Biber - The Mystery Sonatas , John Holloway (violin), Davitt Moroney (harpsichord and organ), Tragicomedia (continuo). published by: Virgin classics / veritas, 1990, p. 53f and p. 60f.

- ↑ One Ciacona in D and one in C; Strangely enough, the one in C is in even measure, but changes in Var. 16-22 in 3/4, and in other variations in 6/4, as well as in triplet meters such as 6/8 and 12/8. See: Johann Pachelbel: Hexachordum Apollinis 1699 , ed. v. HJ Moser and Tr. Fedtke, Kassel: Bärenreiter 1958/1986, pp. 36–42 (C) and pp. 43–48 (D).

- ↑ In the suites in F minor and D major, and a single piece in G. See: Georg Böhm, Complete Works for Harpsichord , ed. v. Kl. Beckmann, Wiesbaden, Breitkopf & Härtel, 1985, pp. 18-19 (F minor), and pp. 36-38 (D major), pp. 54-55 (G major).

- ^ In Musicalisches Blumenbüschlein from 1695 in the last suite in G; and in Musicalischer Parnassus from 1738 in the suites: Euterpe, Erato, Melpomene. Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer, Complete Works for Keyboard Instrument (including: "Blumenbüschlein" (1698) and Musical Parnassus (1738?)), Ed. v. Ernst von Werra, Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, (originally 1901).

- ^ Johann Krieger, Six musical parts (Nuremberg 1697), in: Johann & Johann Philipp Krieger, Complete Organ and Clavierwerke I , ed. v. Siegbert Rampe and Helene Lerch, Kassel et al .: Bärenreiter, 1995, pp. 88-96.

- ↑ z. B. in his keyboard suites in D major “July” and E major “November”. Christoph Graupner, monthly clavier fruits (1722) , facsimile, prés. par Oswald Bill, publ. sous la dir. de J. Saint-Arroman, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 2003, pp. 82–84 (July) and pp. 122–123 (November).

- ^ George Frideric Handel: Keyboard Works for solo instrument, ..., New York: Dover Publication, 1982, pp. 133-138.

- ^ George Frideric Handel: Keyboard Works for solo instrument, ..., New York: Dover Publication, 1982, pp. 120-132.

- ↑ Georg Friedrich Handel, Piano Works I - Various Suites, Part a (Wiener Urtext Edition) , Vienna / Mainz: Schott / Universal Edition, 1991, pp. 11–29 and p. XXX (preface to the transmission of sources).

- ↑ Siegfried Behrend: Joh. Seb. Bach (1685–1750), Chaconne in D minor arranged for guitar (= The concert guitar. A collection from the repertoire of Siegfried Behrend. ) Music publisher Hans Sikorski, Hamburg 1957 (= Edition Sikorski. Volume 482).

- ↑ z. B. in the Serenade in C major K 352 in the Concentus musico-instrumentalis , Nuremberg 1701. See the CD recording: Johann Joseph Fux: Concentus musico-instrumentalis I, Armonico Tributo Austria, Lorenz Duftschmid, published by: Arcana, 1998.

- ↑ See the CD: Overtures for the Hamburg Opera (Music or the Hamburg Opera) , Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, published by: harmonia mundi France, 2004.

- ^ Walter Siegmund Schultze: Georg Friedrich Händel , VEB Deutscher Verlag für Musik Leipzig 1980, p. 98 and p. 208.

- ↑ George Balanchine created a choreography for it, together with the dance of blessed spirits and a pas de deux .

- ↑ Mozart also composed a Passacaille for Idomeneo : Mozart - The Overtures (Complete Edition) , Basler Sinfonieorchester, Moshe Atzmon, published by: Ariola-eurodisc, 1974 (3 LPs).

- ↑ Johann Mattheson: The perfect Kapellmeister 1739 , facsimile, ed. Margarete Reimann, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1954 / 5th edition 1991, p. 233.

- ↑ Girolamo Frescobaldi, Toccate d'Intavolatura di Cimbalo…, Libro Primo , Rome 1615 and 1637. New edition by Pierre Pidoux, Kassel: Bärenreiter, pp. 77–85.

- ↑ Manuscript Bauyn,…, deuxième part: Pièces de Clavecin de Louis Couperin, … , Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 2006, p. 114 f.

- ↑ Thomas Schmitt: Passacaglio is actually a Chaconne. To distinguish between two musical composition principles , In: Frankfurter Zeitschrift für Musikwissenschaft. Vol. 13, 2010, ISSN 1438-857X, pp. 1–18, (PDF; 364 kB).

- ↑ See § 135 in: Johann Mattheson, “XVII. The Ciacona, Chaconne, with her brother, or her sister, the passaglio, or Passecaille. ”, In: Der perfe Kapellmeister 1739 , facsimile, ed. Margarete Reimann, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1954 / 5th edition 1991, p. 233.

- ↑ On Freillon-Poncein, L'Affilard, Brossard, Montéclair and Pajot, see: Jan van Biezen: "Het tempo van de Franse barokdansen" (The tempo of French Baroque dances), in: Tempo in de Achttiende eeuw , red. K. Vellekoop, Utrecht 1984 (Stimu), pp. 7-25, pp. 37-59. (Dutch). An English summary of the article on: http://www.janvanbiezen.nl/frenchbarok.html (as of August 11, 2017).

- ↑ On L'Affilard 1705 see also: Erich Schwandt: L'Affilard on the French Court Dances , in: The Musical Quarterly. Volume LX, Issue 3, 1 July 1974, pp. 389-400, doi: 10.1093 / mq / LX.3.389 .

- ↑ D'Alembert 1759 means: "La passacaille ne differe de la chaconne qu'en ce qu'elle est plus lente, plus tendre, ..." (= The Passacaille does not differ from the Chaconne, except that it is slower, sweeter ( softer),…). See: Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert : Élémens de musique, théorique et pratique, suivant les principes de M. Rameau , Chez C.-A. Jombert, Paris 1759, p. 169 (see also: https://books.google.at/books?id=yz0HAAAAQAAJ&pg=PR12&hl=de&source=gbs_selected_pages&cad=2#v=onepage&q&f=false )

- ↑ Rousseau 1768 writes: “PASSACAILLE:… Espèce de Chaconne dont le chant est plus tendre et le mouvement plus lent que dans les Chaconnes ordinaires. … ”(“ PASSACAILLE:… A kind of Chaconne, the melody of which is more tender (lovelier, more flirting) and the movement is slower than the ordinary Chaconne… ”). See: Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Passacaille , in: Dictionnaire de musique , Paris 1768, p. 372.See also on IMSLP: http://imslp.org/wiki/Dictionnaire_de_musique_(Rousseau,_Jean-Jacques) , seen on 12. August 2017.

- ↑ In more syllabary form: “... Meter and rhythm support the character differentiation: the ciaccona gets through a cycle after only two groups of three beats; the passacaglia takes more time to go about its business, not reaching the end of a cycle until after four groups of three beats. "See: Alexander Silbiger: Bach and the Chaconne , in: Journal of Musicology 17 (1999), p. 358 Quoted here from: Thomas Schmitt: "Passacaglio is actually a Chaconne .... ", In: Frankfurter Zeitschrift für Musikwissenschaft. Vol. 13, 2010, pp. 1–18, here: p. 5.

- ↑ Lully - Armide , G. Laurens, H. Crook, V. Gens, Collegium Vocale, Chapelle Royale, Ph. Herreweghe, published by: harmonia mundi France, 1992 (2 CDs). (The Passacaille is in Act 5, Scene 2).

- ↑ In addition to d'Anglebert's own creations, there are also harpsichord versions of the Lully chaconnas from Armide , Galathée , Phaëton . See: Jean-Henry d'Anglebert, Pièces de Clavecin - Édition de 1689 ,…, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 1999, pp. 63–66.

- ↑ Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer, Complete Works for Keyboard Instrument , ed. v. Ernst von Werra, Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, (originally 1901), pp. 12–13 (Passacaille in a), pp. 30–32, (Chaconne in G), p. 44 (Chaconne in a), p. 50 (Chaconne in e), pp. 54-56 (Chaconne in F) and pp. 70-74 (Passacaglia in d).

- ↑ Hermann Keller : The Chaconne in G minor by - Vitali? In: New magazine for music. Vol. 125, No. 4, April 1964, ISSN 0170-8791 , p. 147.