Jacques Champion de Chambonnières

Jacques Champion de Chambonnières (* late 1601 or 1602 in Paris ; † before May 4, 1672 ibid) was a French harpsichordist and composer of the Baroque era. He was the founder of the French harpsichord school ( clavecinists ).

Live and act

Chambonnières came from a family of musicians. His grandfather Thomas Champion, called Mithou (approx. 1525 - approx. 1580), and his father Jacques Champion, Sieur de la Chapelle (around 1555–1642), were organists at the French royal court. His grandfather also performed as a dancer, and his father was also a harpsichordist ( joueur d 'espinette ). Chambonnières was the first, and initially only, child of his father from his second marriage to Anne, the daughter of Robert Chastriot, Sieur de Chambonnières. The resounding name Chambonnières came from the maternal grandfather.

As early as September 1611, his father made him eligible for the office of royal harpsichordist. Nevertheless, Chambonnières had to buy this office from his family for a high price after 1631 and pay his mother and his two younger siblings 3,000 livres after his father's death. This could have been a reason for the financial difficulties he later ran into.

Chambonnières was no later than 1632 "gentilhomme ordinaire de la Chambre du Roi " under Louis XIII (1610-1643). Around this time he was already famous as a composer and outstanding interpreter of wonderful harpsichord pieces ( Pièces de clavecin ), and Mersenne praised him in 1636 for “... the beauty of his works, the beautiful touch, the ease and fluency of the hands together with a very fine ear , so that one can say that this instrument has found its last (greatest) master. ”.

In addition to his work at court, Chambonnières began to organize musical gatherings around 1641, which took place twice a week on Wednesdays and Saturdays and where 10 musicians performed various vocal and instrumental music - apparently in the style of the Italian accademie . In 1655 Christiaan Huygens reported to his father Constantijn about such an " assemblée des honnestes curieux ", where Chambonnières had played "admirably beautiful" (" admirablement bien ").

After the death of his father in 1642, Chambonnières officially carried the title " joueur d'espinette ". He had numerous students, and even Johann Jacob Froberger was keenly interested in getting to know pieces of music from him. According to Titon du Tillet (1732), Chambonnières met the three brothers Louis, Charles and François (I) Couperin while he was on his mother's estate near Chaumes-en-Brie and the three serenaded him on his name day played. He recognized Louis Couperin's talent and suggested that he come to Paris with him: “... Louis Couperin accepted this proposal with pleasure and Chambonnières introduced it to Paris and at court. ... ".

Between 1635 and 1654 Chambonnieres also took part as a dancer in some Ballets de Cour , especially in the famous Ballet Royal de la nuit on February 23, 1653, in which the 14-year-old Louis XIV appeared for the first time as the sun god.

Chambonnières is said to have lived well beyond his means. In any case, he got into more and more financial difficulties in the mid-1650s: in 1656 he tried to get a temporary job with Queen Christine of Sweden and to organize a concert tour through Brabant with the help of Christiaan and Constantijn Huygens; both projects did not materialize. In 1657 Chambonnières had to sell a piece of land to his mother, and a few months later his second wife Marguerite Ferret ordered an official separation of her possessions and she "... sold ... some objects belonging to him to compensate for the loss she suffered in the marriage ..." . To make matters worse, his star was slowly sinking at court too, because in February of the same year 1657 Louis XIV had chosen the young Étienne Richard as his harpsichord teacher.

After Jean-Baptiste Lully had become “ surintendant de la musique de la chambre ” in 1661 , the final “case” of Chambonnières came about because he had allegedly refused to play the figured bass in one of Lully's works (the gambist Jean Rousseau claimed later, Chambonnières could not play by numbers). According to Titon du Tillet (1732), Louis Couperin was offered the position of his former friend and patron, but he is said to have turned it down out of loyalty; Couperin died in the same year anyway.

On October 23, 1662, the 60-year-old Chambonnières sold his office as joueur d'espinette for 2000 livres to Jean-Henri d'Anglebert , but he kept a pension of 1800 livres a year. The aged composer made a few more plans to find a job abroad (including in Brandenburg), but these failed. He gave one last concert in 1665 for the Duchess of Orléans .

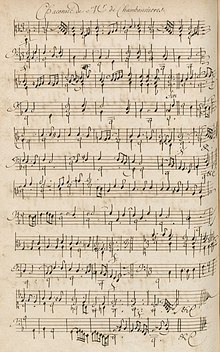

Chambonnières published two books Pièces de clavessin in 1670 .

He probably died in April 1672. In his estate there were: A luxuriously furnished “espinette” with chinoiserie and a cover painting of Parnassus; a harpsichord worth 60 livres and a simpler one worth 20 livres; and a shelf. One of these harpsichords was perhaps Joannes Couchet's two-time instrument , which Constantijn Huygens had mentioned in a letter in 1655.

Chambonnières was married twice, first from around 1621/22 to the beginning of the 1650s with Marie Leclerc. He married his second wife Marguerite Ferret on December 16, 1652.

plant

Chambonnières had a great influence on the development of French and international harpsichord music, especially the development of the baroque suite . Although there is very little French keyboard music known from his predecessors, it is clear that with him there was a complete change in style. He is the creator of his very own French harpsichord style, which is characterized by great elegance and provided the foundation for French music up to the 18th century; characteristic is the style brisé , an openwork, flowing type that is derived from contemporary lute music.

Typically French is also the concentration on dances, which in Chambonnières get a stylized, graceful-elegant face, with often wide-ranging melodic arcs, and with interesting contrapuntal-moving middle and lower voices. He also used emblematic titles from time to time, which later became so popular (e.g. Sarabande 'Jeunes Zephirs' ), sometimes alluding to certain personalities ( Sarabande de la Reyne , Courante de Madame ).

In addition to the two times 30 pieces in his Pièces de clavessin from 1670, Chambonnières left numerous other dances, especially in the famous Bauyn manuscript , but also in many other manuscripts: According to Bruce Gustafson, his music was “more popular than the works of any other French harpsichordist 17th century ". The two most popular pieces were the Courante “Iris” and the Sarabande “Jeunes Zephirs” .

Chambonnières' work extends to a total of 148 dances. What is interesting is the large number of 67 courants compared to 15 allemandes , 31 sarabands , and 21 gigues . Chambonnières wrote 4 pavans , which according to tradition are all in three parts. His gaillards bear little resemblance to the original dance, they are relatively slow and of a complex, ostentatious character. Of the four Chaconnes of Manuscript Bauyn is a (f to 45v See illustration.) In F major in Manuscript Parville handed down under the name of Louis Couperin, where it has two couplets more - if Louis has just added these last two couplets , or at least the whole piece comes from him, is unclear. The last piece of the second volume Pièces de clavessin of Chambonnières is at that time still very newfangled Menuet .

In the Manuskrit Bauyn , Chambonnière's dances are usually only listed according to key and character; they have to be put together into suites by the interpreter himself (exception is a suite in B flat major). His Pièces de clavessin are a great aid to orientation. It must be emphasized that Chambonnières had a much looser and more imaginative idea of the order of the suite than Froberger. Although the basic sequence of Allemande-Courante-Sarabande can also be clearly seen in him, a first important difference is that most suites have three Couranten in succession, more rarely two. A standard sequence of sentences is: Allemande-Courante-Courante-Courante-Sarabande.

Other movements - such as jigues or a gaillarde - are usually appended at the end, but there are also suites with a jig or gaillarde in second place. A very eccentric case is the Suite in G minor from Pièces de clavessin II with the sequence of movements: Pavane - Gigue - Courante - Gigue.

The decorations are of the greatest importance for the effect, they belonged to the secrets of the good interpreter and composer in Chambonnière's time (as in Italy): In the manuscripts the pieces are almost undecorated, the decor is left to the artist's art and imagination. In his published Pièces de clavessin, Chambonnières brought an "ideal version" of his pieces with prescribed decorations for the first time. He used seven different characters (for comparison: d'Anglebert used 29 decorative characters in 1689). This was an important step with which he confided important secrets of his craft to a general public for the first time - not by chance, but only two years before his death.

If Le Gallois (1680) is to be believed, Chambonnières himself, in his prime, probably would not have strictly adhered to his prescribed ornaments: “... every time he played a piece, he mixed new beauties into it with reservations, passages , and various decorations, with double strokes. After all, he made her so different through all these beauties that you found new charms every time. "

student

- Jean-Henri d'Anglebert

- Robert Cambert

- Louis Couperin

- Jacques Hardel (around 1643–1678)

- Guillaume Gabriel Nivers

literature

- Alan Curtis, foreword to: Louis Couperin, Pièces de Clavecin ( Le Pupitre LP. 18 ), Ed. par Alan Curtis, Paris: Heugel, 1970.

- Bruce Gustafson, "Champion, 1st Thomas, 2nd Jacques (II), sieur de la Chapelle, 3rd Chambonnières, Jacques Champion", in: Music in the past and present (MGG), personal section , vol. 4, Kassel: Bärenreiter , 2000, pp. 698-706.

grades

- Jean-Henry d'Anglebert, Pièces de Clavecin - Édition de 1689 , Facsimile, publ. sous la dir. de J. Saint-Arroman, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 1999.

- Manuscript Bauyn, première partie: Pièces de Clavecin de Jacques Champion de Chambonnières , Facsimile, prés. by Bertrand Porot, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 2006.

- Jacques Champion de Chambonnières, Les Pièces de Clavessin, Vol. I & II , Facsimile of the 1670 Paris Edition, New York: Broude Brothers, 1967.

- Louis Couperin, Pièces de Clavecin ( Le Pupitre LP. 18 ), Ed. par Alan Curtis, Paris: Heugel, 1970.

Web links

- Catalog of works (by Bruce Gustafson)

- Works by and about Jacques Champion de Chambonnières in the catalog of the German National Library

- Sheet music and audio files by Jacques Champion de Chambonnières in the International Music Score Library Project

Remarks

- ↑ Bruce Gustafson, "Champion, ..., 3. Chambonnières, Jacques Champion", in: Music in Past and Present (MGG), Person Teil , Vol. 4, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2000, p. 703. This story sounds a bit strange and unbelievable, since Chambonnières himself had given concerts with other musicians for years.

- ↑ Sarabande de la Reyne : alluding to Queen Marie Thérèse , the wife of Louis XIV, who was of Spanish origin, just like the Sarabande. Courante de Madame : probably alluding to Henriette d'Orléans, the sister-in-law of Louis XIV, who was called "Madame".

- ↑ This is a very important difference e.g. B. on François Couperin , who demanded that his pieces should be played exactly as he had them printed, without leaving out or adding any decoration (preface to volume 3 of the Pièces de clavecin , 1722). Something similar can be assumed of d'Anglebert, whose personal style is strongly influenced by the large number of selected decorations.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bruce Gustafson, "Champion, 1st Thomas, 2nd Jacques (II), sieur de la Chapelle", in: Music in Past and Present (MGG), Person Teil , Vol. 4, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2000, p. 699 .

- ↑ Bruce Gustafson, "Champion, ..., 2. Jacques (II), sieur de la Chapelle, 3. Chambonnières, Jacques Champion", in: Music in past and present (MGG), personal section , vol. 4, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2000, p. 699 and p. 701.

- ↑ Bruce Gustafson, "Champion, ..., 2. Jacques (II), sieur de la Chapelle, ...", in: Music in Past and Present (MGG), Person Teil , Vol. 4, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2000, p. 700 .

- ↑ ""… la beauté des mouvements, le beau toucher, & la legereté, & la vitesse de la main jointe à une oreille tres-delicate, de sorte qu'on puet dire que cet Instrument à ( sic ) rencontré son dernier Maistre " (Harmonie Universelle, 1636, Préface générale, fol. A (v) ", in: Bruce Gustafson)," Champion,…, 3. Chambonnières, Jacques Champion ", in: Music in past and present (MGG), personal section , vol 4, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2000, pp. 701–706, here: p. 701.

- ↑ Bruce Gustafson, "Champion, ..., 3. Chambonnières, Jacques Champion", in: Music in Past and Present (MGG), Person Teil , Vol. 4, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2000, p. 702.

- ^ Titon du Tillet in: Le Parnasse Français (1732). Here after: Alan Curtis, foreword to: Louis Couperin, Pièces de clavecin ( Le Pupitre LP. 18 ), Ed. par Alan Curtis, Paris: Heugel, 1970, p. XII.

- ↑ Bruce Gustafson, "Champion, ..., 3. Chambonnières, Jacques Champion", in: Music in Past and Present (MGG), Person Teil, Vol. 4, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2000, pp. 702–703.

- ↑ Bruce Gustafson, "Champion, ..., 3. Chambonnières, Jacques Champion", in: Music in Past and Present (MGG), Person Teil , Vol. 4, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2000, p. 703. However, the question is how much you can give on anecdotes that were rumored 60 or 70 years later.

- ↑ To translate the French term “ espinette ” here with “spinet” would be a bit dangerous, considering the fact that in the 16th and 17th centuries it could also mean the harpsichord. Chambonnières' traditional title was " joueur d'espinette " (literally "spinet player"). Similar to the English term “ virginalls ” (otherwise always in the plural!) In no way coincides with today's term “virginal” - and certainly not referring to the Flemish muselar - but included all Kiel instruments, especially the harpsichord.

- ↑ Bruce Gustafson, "Champion, 1st Thomas, 2nd Jacques (II), sieur de la Chapelle", in: Music in Past and Present (MGG), Person Teil , Vol. 4, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2000, p. 704 .

- ↑ The Courante “Iris” is still preserved in 13 manuscripts up to the 1750s, the Sarabande “Jeunes Zephirs” in 10; both are also in the Pièces de clavessin from 1670. See: Bruce Gustafson, "Champion, 1st Thomas, 2nd Jacques (II), sieur de la Chapelle", in: Music in Past and Present (MGG), Person Teil , Vol . 4, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2000, p. 704.

- ↑ It was quite common for one composer to revise or add to the work of another, so there are doubles from Louis Couperin to works by other composers. Chaconnas are much more common in Louis Couperin's work than in Chambonnières, and the piece in question actually corresponds to the style of Louis. In view of the fact that the French dances of this period were quite clearly based on prototypes, it is still not clear who made it.

- ↑ The Chaconne in the version of the MS Parville is published in (and is mentioned in the foreword to): Louis Couperin, Pièces de Clavecin ( Le Pupitre LP. 18 ), Ed. par Alan Curtis, Paris: Heugel, 1970, foreword p. XIII and p. 117–119 (Chaconne in F).

- ^ Jean-Henry d'Anglebert, Pièces de Clavecin - Édition de 1689 ,…, Courlay: Édition JM Fuzeau, 1999.

- ↑ “… toutes les fois qu'il (Chambonnières) joüoit une pièce il méloit de nouvelles beautés par des ports de voix, des passages, & des agréments differents, avec des doubles cadences. Enfin il les diversifioit tellement par toutes ces beautez differentes qu'il y faisoit toûjours trouver de nouvelles graces. ”(Le Gallois, 1680, p. 70). see: Bruce Gustafson, "Champion, ..., 3. Chambonnières, Jacques Champion", in: Music in Past and Present (MGG), Person Teil , Vol. 4, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2000, p. 705.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Champion de Chambonnières, Jacques |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French harpsichordist and composer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1601 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Paris |

| DATE OF DEATH | before May 4, 1672 |

| Place of death | Paris |