Breton music

The Breton music has in comparison to other music in France independent tradition. The Brittany is in the northwest of France, is linguistically insular Celtic area.

Types

Breton music can be divided into two types depending on its "intended use":

Dance music (fest-noz)

This is preferably performed by instrumental or vocal groups at Fest-noz or Bal Folk . Both instrumental and vocal repertoire is almost always performed in the manner of alternating chant (Bret .: Kan ha diskan), with the partner joining the performance shortly before the end of a musical phrase. This type of music is designed entirely for danceability. Unlike in the neighboring Celtic countries ( Scotland , Ireland , Wales ) it is the rule that people actually dance, although at some festivals the number of dancers can go into the thousands. The Breton dances mostly take the form of chain, row or circle dances. The round dance can involve a large number of dancers.

Rhythms

The dominant rhythm is the 4/4 time, which is sometimes played straight (Dañs Plin, An Dro, Pache Pie), but more often dotted or triplet-swinging (for example Laridée 8-temps, Gavotte de Montagne, Dañs Fisel , Ronds de St. Vincent, Kost ar C'hoad). The 3/2 time is less common (Hanter Dro, Laridée 6-temps). Odd measures are even rarer, as can be seen especially in the (non-danceable) marche . Some dances alternate between 6 and 4 bars. (Hanter Dro-An Dro, Tricot).

Compared to Irish music, it is noticeable that the melodies have far more syncopation , while Irish jigs or reels usually have one note of the melody on each beat.

instrumentation

The classical instrumentation consists of, even if it was found regionally different in the 19th century

- a singing duo; or

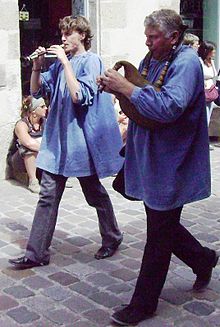

- a duo with the Breton shawm , the bombarde and the bagpipes Binioù kozh or

- a duo with violin and accordion .

- clarinet

The harmony between Bombarde and Binioù kozh is apparently particularly characteristic of Brittany today. Both instruments are loud, whereby the bombard can be described as piercing and garish. The sound is similar to that of the Rauschpfeife and the zurna , but it is even sharper and richer in overtones than the two instruments.

Since the folk revival of the 1970s, however, numerous other instruments have found their way. So include electric bass , percussion / drums , guitar and Irish wooden flute Breton squad for music groups. The combination of vocal and instrumental music is also absolutely common today.

Narrative songs

These include, for example, seafarers' songs and lamentations, the so-called gwerzio ù. This type of music is traditionally often performed by an unaccompanied singer, who sings in a relatively high pitch.

The gwerzioù are usually performed in a free rhythm that depends on the content of the piece and the singer's emotion. Gwerzioù can sing about historical events or legends, but also current events such as the oil spill on the Breton coast after the sinking of the freighter Amoco Cadiz , which was celebrated in this form. Gwerzioù are mostly sung in the Breton language .

The most famous performers of this form of song include u. a. Erik Marchand , Yann-Fañch Kemener , Denez Prigent and Annie Ebrel .

history

By the Second World War , the Breton musical tradition was in decline. The first sign of revitalization was the appearance of the Bagadoù in the 1950s. A Bagad is a group based on the model of the Scottish Pipes & Drums , in which, in addition to traditional bombards and binoù kozh, Scottish Great Highland Bagpipes , deeper variants of the bombarde and percussion instruments also play. The best-known representatives of this genre are the Bagad Kemper from the city of Quimper (Bret. Kemper ) and the Bagad de Lann-Bihoué of the French Navy from Lorient .

The big breakthrough did not come until the 1970s, however. Alan Stivell was the first musician who, under the influence of Anglo-Saxon folk-rock, combined Breton folk music with electric guitar , drums and other rock instruments. His celebrated appearances at the Olympia in Paris are probably one of the most influential testimonies to Breton music of the 20th century, also because he hit the nerve of the times with his emphasis on the Breton language and the recourse to Celtic mysticism.

In addition to electrical and electronic instruments, the introduction of the Celtic harp into Breton music is a credit to Stivell. However, this innovation seems to have had a far less lasting effect, because the harp is rarely found in today's line- ups .

Like Stivell, Tri Yann from Nantes also relied on the fusion of folk music, folk and rock early on, singing almost exclusively in French and being more political than mystical in content. At the same time Diaouled ar Menez (German: "The mountain devils") became known. They only sing Breton lyrics.

After the “wild years”, largely influenced by Stivell and Tri Yann, groups dominated in the late 1980s and 90s that belonged to the genre of folk rather than folk rock. Groups like Gwerz , Skolvan or Bleizi Ruz show that their interpretations are partly strongly influenced by the Irish folk revival. Jean-Michel Veillon , flautist of the Barzaz group, established the Irish wooden flute in Brittany. Their music largely dispenses with distorted electric guitars and hammering drum batteries, but not innovation. Bleizi Ruz and Gwerz, for example, integrated elements of the music of Southeastern Europe , especially from Bulgaria and Romania , including the odd rhythms that are common there.

With his combinations of traditional Breton music, jazz improvisation and classical romanticism, the pianist Didier Squiban has enriched the instruments of modern Breton music with the piano.

Overall, world music influences have increased significantly in Brittany since the 1990s. The singer Erik Marchand released an album with An Tri Breur in 1991 , on which he interpreted Breton gwerzioù and dances accompanied by Indian tablas and the Arabic lute oud . In 1993, his collaboration with the Taraf de Caransebeş Roma chapel from the Romanian Banat received rave reviews.

In the meantime, numerous other interpreters have entered into similar collaborations, so that mergers between Breton and Central African musicians or a Berber-Breton co-production like the Thalweg group no longer cause any particular excitement. It was rather unusual when, in 1998, L'Occidental de Fanfare , a high-quality joint production by Breton musicians with musicians from another French region, Gascon , first hit the festival stages in Europe.

The more recent developments also include the fusion of traditional Breton music with hip-hop (for example Manau ), rap , Raï ( Startijenn ), techno or even grunge in the Nirvana style. The singer and musician Pascal Lamour mixes Breton singing and playing Breton instruments with ambient and trance music. Overall, the Breton music scene remains innovative and lively in the 21st century.

Festivals

The major Breton festivals such as the Festival Interceltique in the city of Lorient , the Festival de Cornouaille in Quimper and the Festival Yaouank in Rennes attract hundreds of thousands of visitors every year.

literature

- Jonathyne Briggs: Sounds French: Globalization, Cultural Communities, and Pop Music in France, 1958-1980 . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2015; Chapter 4: Sounds Regional: The World in Breton Folk Music , pp. 110-143, ISBN 9780199377091

- Jean-Michel Guilcher: La tradition popular de danse en basse-bretagne . Coop Breizh, Chasse-Marée / Armen, Spézet-Douarnenez 1995 nouvelle édition

- Yves Guilcher: The traditional French civilization paysanne à loisir revivaliste . Librairie de la Danse, FAMDT, 1998 Courlay

- Polig Monjarret: Tonioù Breizh-Izel . Dastum 2005, ISBN 2-908604-08-6 (most important collection of traditional sheet music)

- Corina Oosterveen: 40 Breton dances with their cultural background . Publishing house of the minstrels Hofmann & Co. KG, Brensbach 1995, ISBN 3-927240-32-X (accompanying CD of the group La Marmotte : Nous les ferons danser )