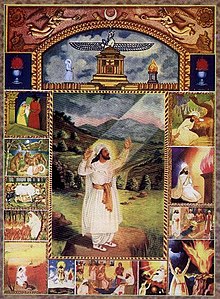

Zarathustra

Zarathustra ( Avestan Zaraθuštra ) or Zoroaster ( Greek Ζωροάστρης Zoroastres), also known as Zarathustra Spitama was an Iranian priest ( Zaotar ) and philosopher. He taught in the second or first millennium BC. BC, in a north-east Iranian language , which later became known as Avestian after his work Avesta , and helped Zoroastrianism, named after him, to later breakthrough as a Persian - Median or Iranian religion, which is why he, for example, "founder of Zoroastrianism", "founder of religion" or called "Reformer". The followers of Zoroastrianism are called Zoroastrians or Zoroastrians . The following in today's India and Pakistan includes in particular the ethnic-religious groups of the Parsees and, to some extent, the Irani .

The name Zaraθuštra probably means “owner of valuable camels” (the interpretation of the fore limb zarat- as “old, precious, gold-colored” is controversial, the rear limb of this composition is generally identified with Avestian -uštra- “camel”). Other forms of name are, for example: Middle Persian Zarduscht, Persian زَردُشت, DMG Zardošt , tooزَرتُشت, DMG Zartošt , Pashtun زردښت Zardaxt , Kurdish Zerdeşt, ancient Greek Ζωροάστηρ Zōroástēr / Ζωροάστρης Zōroástrēs .

The ancient Greeks saw in him a sage; in the eyes of the French philosophers, including Voltaire , he was a mediator in questions of religious faith. The statements in oriental studies , which have not yet made a final clarification about Zarathustra's work, are equally diverse . It remains unclear in which social and geographical environment he worked, whose ideas he took up or on what basis he built his teaching. He is considered by some to be the founder of the first monotheistic religion based on the belief in Ahura Mazda .

The chronological classifications made by historians so far are based on various sources, from whose interpretation theories and theses about the work of Zarathustra were developed that ignore the few archaeological references. For example, Ammianus Marcellinus was the first to establish a connection to the Achaemenids via Wishtaspa (father of Darius I ) . The fact that Wishtaspa was a common name for many centuries, however, excludes an exact chronological assignment.

swell

One source on Zarathustra is the Avesta , a collection of sacred verses that have been transmitted orally in the Avesta language. It should be a divine revelation. According to a controversial thesis, the earliest written record may have been made in Aramaic or the Parthian script derived from it , around the 1st century AD or shortly before. A version from the 3rd century AD could have been passed on in the Pahlavi script, which is also derived from the Aramaic script , the letters used allow ambiguous translations. In the Sassanid period (224 to 651 AD) the first written down in the newly conceived Avestan script was made . It made it possible to reproduce the texts that had been handed down mainly orally over the centuries, in a very precise way. The attempts of Zoroastrian scholars to translate the Avestan models uniformly into the so-called Zend-Avesta in the Sassanid period and in the Middle Ages failed. To date it has not been possible to present even an undisputed translation of the Avesta. Another source on Zarathustra is a collection of mostly liturgical texts that emerged from oral tradition and were written down in the 6th century AD and have only survived in fragments.

Linguists and religious scholars come to an approximation neither in linguistic-textual understanding nor in interpretation with regard to the determination of a main source that could lead to Zarathustra. This is especially true for the 859 lines of the “ 17 Gathas of Zarathustra ” (“Chants, Sermons”). Here, too, a clear translation is not possible, which is why every reading carried out means a different new version compared to existing older texts. In addition, the obvious parallels to ancient Indian texts raise more questions than answers and so far do not allow a certain interpretation to be confirmed.

origin

According to legend, Zarathustra's mother came from Raga . In modern research there is disagreement about Zarathustra's place of birth and his place of work, which is why several possibilities are controversially discussed. Touraj Daryaee (USA) gives Balkh in the north of what is now Afghanistan as the place of birth.

Northeast Iran and Sistan

Notes in the Avesta are interpreted in the form that Zarathustra could have been in Sistan (in today's border area between Iran and Afghanistan). Sistan played an important role in the Persian world of belief, but the cause cannot be traced back to Zarathustra. It was not until the post-Zoroastrian era that attempts were made to establish connections and common ground, as the sacred mountain Kuh-e Hajj on Lake Hamun made Sistan a Mecca for Zoroastrian supporters due to its secluded desert location.

Through many periods of Sistan's history, the oasis led a life of its own due to its difficult-to-reach location and developed completely independently of the respective religious currents. Due to the religious attraction of Sistan, it is therefore to a small extent likely that Zarathustra could have worked here temporarily, although there is no evidence of an early Ahuramazda belief in this region. Because of the documented early Iranian migration from east to west, however, there may have been short-term points of contact.

Media and Azerbaijan

In the regions of the Median Confederation , the originally Persian territory of Parsua is already around 1000 BC. Attested in Assyrian inscriptions. In the following years it is mentioned more and more frequently with the mention of Anschan . Archaeological research confirms decisive political and social upheavals in what is now Azerbaijan during the same period . Azerbaijan was, among other things, the destination of the east-west migration, during which not only Indian tribes but also eastern Iranian nomads immigrated. The archaeological evidence shows that the local culture mixed with that of the new immigrants.

In connection with the settling down and amalgamation of nomadic and agricultural cultures, there are also clear indications of the development of a new religion. In the 8th century BC The medical name Mazda appeared for the first time in the 3rd century BC , only missing the addition Ahura. Zarathustra never mentioned the name Ahuramazda in his teaching either, but initially only Mazda or Ahura. It was to be reserved for the Achaemenids, not until 522 BC. Under Darius I to unite both names to Ahuramazda.

The name component Wischt aspa (horse) refers to the horse breeding areas characteristic of the media and Azerbaijan, from which the Assyrians obtained their horses. Zarathustra named among other things the Median priestly caste Magawan his followers , whose heartland was undoubtedly Azerbaijan.

Lifetime

There are various more or less convincing opinions on the dating of Zarathustra's lifetime:

- Zarathustra lived around 600 BC This determination is based on the tradition of the Islamic scholar Biruni , who, according to Sassanid tradition, put the date of Zoroaster's calling at 258 years before Alexander . Wiesehöfer , Lommel , Altheim and Walther Hinz rely on this . According to this, Zarathustra has from 630 BC BC to 553 BC Lived. Hinz suspects a meeting of Zarathustra and Cyrus II (585-530 BC), who did not adopt his teachings, but showed himself tolerant of all religions.

- A confirmation of the worship of the supreme god Ahura Mazda named by Zarathustra was only proven to be certain under Darius I (* 549 BC; † 486 BC). This caused Hertel and Herzfeld, as reported by Ammianus Marcellinus , to identify Prince Vistaspa , who promoted Zarathustra, as Hystaspes, the father of Darius I, making Zarathustra the older contemporary of the son.

- The orientalist Thomas Hyde points out that the Syrian scholar Abū l-Faradsch writes in his "Dynasty History" that Zarathustra was a student of the exiled Jew Daniel in Babylon . According to biblical tradition, he belonged to that part of the population of Judah that Nebuchadnezzar II sent into Babylonian captivity, which lasted from 598 to 539 BC. Chr. Lasted.

- Zarathustra had around 1000 BC Lived. Take that u. a. Eilers and Stausberg. This dating assumes the appearance of Zarathustra in the area around Bactria .

- Such an average dating could hardly be reconciled with the safe occurrence of the Iranian tribes of the Medes and Persians . Zarathustra is also said to have worked as a priest or magician before his “calling experience” . For these reasons Frye determined the work of Zarathustra for the time around 800 BC. Chr.

- Zarathustra had around 1800 BC Lived, more precisely: was 1768 BC. Born in BC. Iranian scholars (Behrūz, Derakhshani) and Mary Boyce in particular hold this view . In the context of the settlement of Persia, Zarathustra's appearance should be seen with the first wave of immigration.

In addition to different scientific methods and arguments, ideological motives also play a role in this discussion. Zoroastrians celebrate his birthday on March 26th.

The teachings of Zoroaster

Main features

The Zoroastrian religion documented in the Avesta and traced back to Zarathustra is monotheistic , the struggle between good and evil shapes belief. The victory of good over evil will come on the day of judgment . Until that day, people are free to choose the right path. The right way is the way of truthfulness. Zarathustra's teaching has three important principles:

- good thoughts

- good words

- good deeds

Ahura Mazda , the wise Lord, created the world on the foundation of truthfulness . The good spirit (Spenta Mainyu) and the evil spirit ( Angra Mainyu ) are twins, through whose cooperation the world exists. So that the good triumphs over the bad, man has to make a decision, because man is the only living being that has been given the opportunity to lead and change. Man can forgive or hate, man is human because he does not let his instincts guide him. It is up to everyone to choose what is good and thus to support Ahura Mazda's fight against evil. It is important here that Zoroastrianism or Ahura Mazda does not force people to do anything. Man is born free as a reasonable being and can come to God only through free decision and personal insight.

There are six aspects of God ( Amesha Spentas ), or seven - see also Haft Sin (seven decorative bowls ), Seven Food , Haft Mewa (seven-fruit drink) and Samanak [seedlings from seven types of grain] in the Nouruz , which are the seven Symbolize virtues of Zoroastrianism. These are in part personified as angelic beings in the Avesta, the holy book of Zoroastrianism:

- The good sense.

- The best truth / truthfulness.

- The desirable kingdom.

- The blessing piety.

- Welfare.

- Do not die.

- The blessing spirit is added by some.

Zarathustra's worship negates any kind of sacrificial acts as it existed in his time in the form of the cults of the Mithras priests. Zarathustra Spitama devoted himself to the fight against this - from his point of view - idolatry and was therefore persecuted. The devotional ceremonies directed at Ahura Mazda were held around an altar of fire with hands raised while the praises were sung.

In this life, man has the choice between good and bad. Provided that the good prevails in the human being, after his death the human arrives over the Činvat bridge into paradise , from which according to an Iranian legend Zarathustra received the Avesta and the "Holy Fire" ( Atar ). For the righteous person the bridge is a wide way, for the other it is narrow as a knife edge.

Continuation of teaching

In a later transformation, especially under the Sassanids , the Zoroastrian religion was supplemented by a god of time, called Zurvan . This four-form God (Ahūra Mazda, goodness, religion and time) stands above God and the devil , who are his sons. Zurvan is the infinite space and the infinite time. With the emergence of God and evil, light is separated from darkness.

Reception in Europe

Philosophy and literature

Pliny the Elder claimed that Zarathustra was the first person to laugh when he was born - which can be interpreted both as evidence of his clarity and as a sign of a diabolical character.

For a long time in Europe, Zarathustra was seen as the prototype of the wisdom teacher. The Renaissance paid homage to him as the guardian of pre-Christian wisdom. The Enlightenment discovered in him the sage from the Orient and herald of a sun religion. In 1751, Guillaume Alexandre de Méhégan dedicated his French text Zoroastre to Frederick the Great : Histoire traduite du Chaladéen. In the learned world of the 18th century, one of the great controversies was whether Zarathustra was a monotheist ( Thomas Hyde ) or a radical dualist ( Pierre Bayle , Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz ). In his “Philosophical Doctrine of Religions” (1793), Immanuel Kant emphasized as an essential feature of the “Parsis, followers of the religion of Zoroaster” that they “have a written religion (holy books)” and “have preserved their faith up to now”, “ regardless of their dispersion ”. For his lectures and publications, Kant was already able to use the German translation published by Johann Friedrich Kleuker 1776–1778 of the work by Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron , the founder of the study of the Zend religion in Europe, Zend-Avesta, ouvrage de Zoroastre , published in Paris in 1771 , like after him, among others, Johann Gottfried Herder in his "Ideas on the Philosophy of the History of Humanity" and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in his lectures "On the Philosophy of Religion" and "On the Philosophy of History". As for Herder, who recognized a kind of philosophical theodicy in Zoroaster's state religion , for Hegel Zarathustra was called Zerduscht , and in his teaching Hegel encountered a pure breath, a breath of the spirit. The spirit rises in her from the substantial unity of nature . Gotthold Ephraim Lessing dedicated the often neglected character Al-Hafi in his drama Nathan the Wise to Zoroastrianism , to whom he originally wanted to dedicate a postscript under the title Dervish .

In the western world, the name Zarathustra has recently been associated with Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophical and poetic work Also sprach Zarathustra , which was written from 1883 to 1885. Since the historical Zarathustra was the first for Nietzsche to differentiate between good and evil, he gave his figure in the book, which for him symbolized the overcoming of all morals and thus pointed beyond the end of the historical epoch that began by historical Zarathustra, the same name.

Zarathustra also appears in Karl May 's stories about the Orient .

music

By Jean-Philippe Rameau one comes tragédie lyrique entitled Zoroastre, named after the main character. The work was premiered in 1749 "par l'Academie Royale de Musique" in Paris. The libretto was the Tragedie Zoroastre by Louis de Cahusac , which was soon translated into German by Giacomo Casanova .

In two further operas, one character each alludes to Zarathustra. In Georg Friedrich Handel's Dramma per musica Orlando, premiered in 1733 (the plot is based on the epic Orlando furioso by Ariosto ), a wise magician named Zoroastro appears. And in Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's opera Die Zauberflöte , which premiered in 1791 , the wise Prince Sarastro and his council of priests represent humanistic ideas. At least one word relationship between Handel's Zoroastro and Mozart's Sarastro with the Persian religious founder Zarathustra can definitely be determined.

Between these operas, the opera L'Huomo based on a libretto by Margravine Wilhelmine (1709-1758) was premiered in June 1754 in the Bayreuth Margravial Opera House , which, according to Argomento, was inspired by the system of Zarathustra's philosophy . The Festa teatrale was premiered on the visit of Wilhelmine's brother Frederick the Great ; the composer was Andrea Bernasconi . The protagonists of this one-act allegorical musical theater are animia and anemone ( anagrams for the female and male soul), who are in the conflict between the bon genius (“the good”) and the mauvais genius (“the evil”) and personified by the people Powers such as “reason”, “impermanence” or “lust” can be influenced.

In the 20th century, Zarathustra gained a certain degree of fame through the symphonic poem Also sprach Zarathustra by Richard Strauss , which was written in 1895, and which explicitly referred to Nietzsche's Also sprach Zarathustra in its title , as well as through Frederick Delius A Mass of Life, a large-scale oratorio based on texts from the same work by Nietzsche.

Others

The Jesuit Giovanni Riccioli named a moon crater after Zoroaster in his New Almagest (1651).

See also

literature

Primary literature

- Ulrich Hannemann (Ed.): The Zend-Avesta. Weißensee-Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 3-89998-199-5 .

Monographs

- Mary Boyce , Frantz Genet: A history of Zoroastrianism. Brill, Leiden / Cologne 1975 ff.

- The early period. 1996, ISBN 90-04-10474-7 .

- Under the Achaemenians. 1982, ISBN 90-04-06506-7 .

- Zoroastrianism under Macedonian and Roman rule. 1991, ISBN 90-04-09271-4 .

- Mary Boyce (Ed.): Textual sources for the study of Zoroastrianism. University Press, Chicago, Ill. 2006, ISBN 0-226-06930-3 .

- Mary Boyce: Zoroastrians. Their religious beliefs and practices. Routledge, London 2007, ISBN 978-0-415-23902-8 .

- Burchard Brentjes : The old Persia. The Iranian world before Mohammed. Schroll, Vienna 1978, ISBN 3-7031-0461-9 .

- Elisabeth Brünner: The Zoroastrian legend in the Zoroastrian tradition. In: Studies on the historical research of antiquity No. 4, Kovač, Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-86064-902-7 (also dissertation, University of Bonn 1998).

- Peter Clark: Zoroastrianism. An introduction to an ancient faith . Sussex Academic Press, Brighton 1998, ISBN 1-898723-78-8 .

- Dastur K. Dabu: Zarathustra and his teachings. A manual for young students . Edition Chamarbaugvala, Bombay 1966.

- Jahanshah Derakhshani: The Aryans in the Middle Eastern sources of the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC Chr. M-Ost, Marburg 2004, ISBN 3-933196-37-X .

- Gherado Gnoli: Zoroaster in History. Bibliotheca Persica Press, New York 2000, ISBN 0-933273-43-6 .

- Walther Hinz : Zarathustra. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1961.

- Albert de Jong: Traditions of the Magi. Zoroastrianism in Greek and Latin literature. Brill, Leiden 1997, ISBN 90-04-10844-0 .

- Heidemarie Koch : Dareios the King heralds ... About life in the Persian Empire (= cultural history of the ancient world . Vol. 55). von Zabern, Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-8053-1347-0 .

- Wolfdietrich von Kloeden : ZARATHUSTRA (actual family name: Spitama), Greek Zoroaster. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 14, Bautz, Herzberg 1998, ISBN 3-88309-073-5 , Sp. 344-355.

- Abdolreza Madjderey : Gatha . The heavenly chants of Zoroaster. Sohrab, Königsdorf 2000, ISBN 3-925819-11-8 .

- Abdolreza Madjderey: What then was Sarathustra really saying? Sohrab, Königsdorf 2002, ISBN 3-925819-14-2 .

- Rustam P. Masani: Zoroastrianism. The religion of the good life. Indigo Books, New Delhi 2003, ISBN 81-292-0049-X (reprint of the London 1938 edition).

- Bernfried Schlerath (Ed.): Zarathustra (= ways of research . 169). Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1970, ISBN 3-534-04121-6 .

-

Michael Stausberg : The religion of Zarathushtra. History, present, rituals. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2002-2004

- 1st vol. 2002, ISBN 3-17-017118-6

- 2. Vol. 2002, ISBN 3-17-017119-4

- 3rd volume 2004, ISBN 3-17-017120-8

- Geo Widengren (Ed.): Iranian Spiritual World. From the beginning to Islam. Holle, Baden-Baden 1961, in particular pp. 133-164 ( Zarathustra, his person, his teaching ).

- Geo Widengren: The Religions of Iran. In book series: The Religions of Mankind 14, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1965.

- Robert C. Zaehner: The dawn and twilight of Zoroastrianism. Phoenix Press, London 2002, ISBN 1-84212-165-0 (reprint of the London 1961 edition)

- Grail Message Foundation (ed.): Zoroaster, Zoro-Thustra, Life and Work of the Trailblazer in Iran. Bernhardt, Vomperberg (Tyrol) 1957, ISBN 3-87860-119-0 .

Essays

- Arthur E. Christensen: The Iranians. In: Albrecht Goetze u. a .: Cultural history of Asia Minor. (= Handbook of Classical Studies. Vol. 2). Beck, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-406-01351-1 (reprint of the Munich 1933 edition).

- Stephan Eberle: Lessing and Zarathustra. In: Rückert studies. Vol. 17 (2006/2007) [2008], pp. 73-130.

- Richard Frye : Zarathustra . In: Emma Brunner-Traut (ed.): The founders of the great world religions. Herder, Freiburg i. B. 2007, ISBN 978-3-451-05937-7 .

- Gustav Mensching : Zarathustra. In: Gustav Mensching: The sons of God. Gutenberg Book Guild, Frankfurt am Main 1959, pp. 191–198.

- Zartusht Bahram Pazhdu: The Book of Zoroaster, or The Zartusht-Nāmah. A Zoroastrian poem. Translated from Persian by Edward Backhouse Eastwick. Lulu, London 2010 [1] .

- Martin Schwartz: The religion of Achaemenian Iran. In: Ilya Gershevitch (Ed.): The Median and Achaemenian Periods. (= The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 2). University Press, Cambridge 1985, ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2 , pp. 664-667.

- Günter C. Vieten, photos: George Shelley: Parsen - The Aryans of God. In: Geo-Magazin. Hamburg 1978, No. 9, pp. 86-108. (Informative [especially among other things the Zoroastrian cult of the dead] experience report).

- Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy: Zarathustras becoming voiced. In: the same: The language of the human race. Volume 2. 1964, pp. 737-772.

Web links

- Literature by and about Zarathustra in the catalog of the German National Library

- Zoroastrian original texts (English)

- Overview of the possible lifetimes (English)

- Sartosht - Iranian-German Cultural Association

Individual evidence

- ↑ Heinz Gaube: Zoroastrismus - The religion of Zarathustra. In: Emma Brunner-Traut : The great religions of the ancient Orient and antiquity. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-17-011976-1 , pp. 102-108.

- ↑ Josef Wiesehöfer: The ancient Persia. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2005, ISBN 3-491-96151-3 .

- ↑ Norbert Oettinger, In: Dietz-Otto Edzard u. a .: Real Lexicon of Assyriology and Near Eastern Archeology . Vol. 8 , de Gruyter, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-11-014809-9 , p. 185.

- ↑ Irani, Dinshah Jijibhoy , article on a prominent member of the Irani religious community in Bombay, Encyclopædia Iranica , accessed December 11, 2017.

- ^ DN MacKenzie: A Concise Pahlavi Dictionary. Routledge Curzon, London / New York 2005, ISBN 0-19-713559-5 .

- ↑ Jürgen Ehlers (ed. And trans.): Abū'l-Qāsem Ferdausi: Rostam - The legends from the Šāhnāme . Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 2002, p. 370

- ↑ Jürgen Ehlers, p. 374 ( Zardhešt )

- ↑ The theater scholar Oswald Georg Bauer gave a lecture on this: The theater of Margravine Wilhelmine: images of people and images of the stage. In: Thomas Betzwieser (ed.): Opera concepts between Berlin and Bayreuth. The musical theater of the Margravine Wilhelmine. Königshausen Neumann, Würzburg 2016 (Thurnauer Schriften zum Musiktheater, Vol. 31), ISBN 978-3-8260-5664-2 , p. 21.

- ↑ See also Michael Stausberg: Faszination Zarathustra, 2 Bde. Berlin 1997/98, especially Bd. 2 The Zoroastre Discourse of the 18th Century (source quoted from: Ruth Müller-Lindenberg: Das L'Homme-Libretto der Wilhelmine von Bayreuth. In: Betzwieser: Opernkonzeptionen 2016, p. 136.)

- ↑ Immanuel Kant: Religion within the limits of mere reason. 1793 In: Kant's works. Volume VI, Academy text edition, Berlin 1968, p. 136f.

- ^ Revised new edition of the Kleuker edition: Ulrich Hannemann (Ed.): Das Zend-Avesta. Weißensee-Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 3-89998-199-5 ; Johann Friedrich Kleuker: Zend-Avesta in miniature. This is Ormuzd's law of light or word of life to Zoroastre. Hartnoch, Riga 1789. Reprint: Kessinger Pub, 2009, ISBN 978-1-120-05637-5 .

- ^ Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: The Zendvolk. In: Lectures on the Philosophy of History. - Chapter 9 .

- ^ Library of Margravine Wilhelmine von Bayreuth, University Library Erlangen-Nürnberg, call number H00 / RL48.

- ↑ Frank A. Kafker: Notices sur les auteurs of dix-sept volumes de "discours" de l'Encyclopédie . In: Recherches sur Diderot et sur l'Encyclopédie. 1989, Vol. 7, No. 7, p. 134.

- ↑ Ivan A. Alexandre : Orlando healed through madness. in the booklet for the CD Erato 0630-14363-2, 1996, p. 29.

- ^ Wilhelmine's French text was brought in versi Italiani from the Poeta della Corte Luiggi Stampiglia . Reprint (Italian / French) in: Péter Niedermüller , Reinhard Wiesend (ed.): Music and theater at the court of the Bayreuth Margravine Wilhelmine (= writings on musicology, vol. 7, published by the musicological institute of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz), Are Edition, Mainz 2002, ISBN 3-924522-08-1 . The Rostock University Library has a libretto print with the German translation by the chief director of the Margravial Bayreuth Opera Philipp Cuno Christian von Bassewitz .

- ↑ Andreas Dorschel : "Philosopher is a rotten word". From Nietzsches to Delius 'Zarathustra'. In: Ulrich Tadday (ed.): Frederick Delius (= music concepts. New episode, issue 141/142). Edition Text + Critique, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-88377-952-2 , pp. 99–116.

- ^ Giovanni Riccioli: Almagestum novum astronomiam veterem novamque complectens observationibus aliorum et propriis novisque theorematibus, problematibus ac tabulis promotam, Vol. I-III, Bologna 1651;

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Zarathustra |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Zoroaster |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Priest, founder of Zoroastrian religions |

| DATE OF BIRTH | between 18th century BC BC and 7th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | between 18th century BC BC and 6th century BC Chr. |

| Place of death | Iran |