Orlando (Handel)

| Work data | |

|---|---|

| Original title: | Orlando |

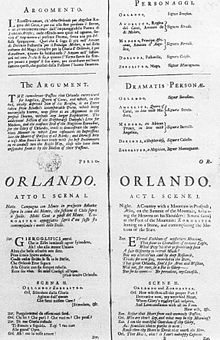

Title page of the libretto, London 1732 |

|

| Shape: | Opera seria |

| Original language: | Italian |

| Music: | georg Friedrich Handel |

| Libretto : | unknown |

| Literary source: | Carlo Sigismondo Capece , L'Orlando, overo La gelosa pazzia (1711) |

| Premiere: | January 27, 1733 |

| Place of premiere: | King's Theater , Haymarket, London |

| Playing time: | 2 ¾ hours |

| Place and time of the action: | Spain , around 770 |

| people | |

Orlando ( HWV 31) is an opera ( Dramma per musica ) in three acts by Georg Friedrich Händel . The subject is based on the epic Orlando furioso (1516/1532) by Ludovico Ariosto , which also provided the material for Handel's later operas Ariodante and Alcina (both 1735).

Emergence

For five seasons, between December 1729 and June 1734, Handel, supported by the impresario Johann Jacob Heidegger , was practically solely responsible for the Italian opera at the King's Theater on London's Haymarket. In the previous decade, the operas had still been produced by the Royal Academy of Music , the so-called first opera academy, a group of aristocrats and country nobles who, in association with other subscribers, financed the operation; but after the failure of the academy in 1728, the management ceded their rights to Handel and Heidegger for five years. The new agreement gave Handel the privilege - rare for a composer of the time - to produce operas largely to his own taste. The repertoire of the serious, heroic operas, the opera series , which were preferred by the first academy, was expanded in February 1730 to include Partenope , the setting of a highly amusing libretto by Silvio Stampiglia , which the academy considered in 1726 Because of his "depravity" had rejected. In addition came pasticci and adaptations of operas leading Italian composers to the stage. In the spring of 1732 the English oratorio experienced a significant innovation, which was incorporated into the music of Handel's previous Italian and English settings of the subject in the form of a revised version by Esther , followed shortly afterwards by a new arrangement of Acis and Galatea as Serenata . Handel had good casts for these productions, above all the great and popular castrato Senesino , who returned from autumn 1730 and who had already played the leading roles in the operas of the first academy.

Not all of the opera's patrons were happy with this situation, and Orlando , the new opera of Handel's fourth season (1732/33), may have contributed to worsening the crisis. According to the dates of the autograph , Handel had completed the first two acts in November 1732: “Fine dell Atto 2 do | Nov. 10 ", and ten days later the entire score:" Fine dell 'Opera GF Handel | Novembr 20 1732. “The first performance in the King's Theater with Senesino in the title role was not scheduled for January 23, 1733, but had to be postponed to January 27. The reason for this delay can be assumed to be the particularly thorough preparation of the new equipment for this staging. But according to Victor Schœlcher , the London Daily Post gave the reason for the postponement of the first performances: "the principal performers being indisposed" ("the leading singers are indisposed"). In the so-called “Opera Register” - a diary of the London opera performances, which for a long time was wrongly attributed to Francis Colman - the author noted on January 27th and February 3rd:

“Orlando Furio a New Opera, by Handel The Cloathes & Scenes all New. D o extraordinary fine & magnificent - performed Severall times until Satturday. "

“Orlando Furioso, a new opera by Handel, all costumes and sets are new. Most excellent and splendid - and performed several times until Saturday. "

Cast of the premiere:

- Orlando - Francesco Bernardi, called " Senesino " ( castrated mezzo- soprano )

- Angelica - Anna Maria Strada del Pó ( Soprano )

- Medoro - Francesca Bertolli ( alto )

- Dorinda - Celeste Gismondi (soprano)

- Zoroastro - Antonio Montagnana ( bass )

Only six performances were scheduled until February 20th. The queen was present on the second evening: her litter was damaged when she left. Handel then resumed Floridante and conducted performances of both his new oratorio, Deborah, and by Esther . Four more Orlando performances followed on April 21; the series of performances ended on May 5th, although another performance was planned for May 8th. Because of the “indisposition” of a singer, presumably the Strada, Floridante was given instead . The audience, which ultimately shrank considerably, included Sir John Clerk, 2nd Baron of Penicuik from Scotland, who was impressed and delivered the following revealing report:

“I never in all my life heard a better piece of musick nor better perform'd - the famous Castrato, Senesino made the principal Actor the rest were all Italians who sung with very good grace and action, however, the audience was very thin so that I believe they get not enough to pay the instruments in the orchestra. I was surprised to see the number of Instrumental Masters for there were 2 Harpsichords, 2 large basse violins each about 7 foot in length at least with strings proportionable that cou'd not be less than a ¼ of an inch diameter, 4 violoncellos, 4 bassoons, 2 Hautbois, 1 Theorbo lute & above 24 violins. These made a terrible noise & often drown'd the voices. One Signior Montagnania sung the bass with a voice like a Canon. I never remember to have heard any thing like him. Amongst [sic] the violins were 2 Brothers of the name Castrucci who play'd with great dexterity. "

“In my whole life I have never heard better music and no better performance: the famous castrato Senesino played the main role, the others were Italians too, who sang and played very skillfully. But there were so few listeners that I fear they won't be able to pay the orchestra musicians. I was surprised by the number of instrumental virtuosos, because there were two harpsichords, two large string basses, at least 7 feet long and with appropriate strings, the diameter of which could not have been less than a quarter inch, 4 cellos, 4 bassoons, 2 oboes, 1 theorbo and more than two dozen violins. These were all terribly loud and often drowned out the voices. A Signor Montagnana sang the bass in a voice that sounded like the thunder of cannons. I don't remember ever hearing anything like it. Among the violinists there were two brothers named Castrucci , who played sweetly and skillfully. "

But after that the work could not be heard until the 20th century. Less than a month after the Dernière , Senesino left Handel's ensemble after negotiating a contract with a competing opera company that was being planned at least in January, soon to be known as the Opera of the Nobility . Identical June 2 press releases from The Bee and The Craftsman state :

“We are credibly inform'd that one day last week Mr. H – d – l, Director-General of the Opera-House, sent a Message to Signior Senesino, the famous Italian Singer, acquainting Him that He had no earlier Occasion for his service; and that Senesino reply'd the next day by a letter, containing a full resignation of all his parts in the Opera, which He had performed for many years with great applause. "

“As we know from a reliable source, Mr. Handel, the general manager of the opera house, sent the famous Italian singer Signor Senesino a message last week informing him that he has no further use for his services; and that Senesino replied by letter the next day that he was giving up all of his roles in the opera, which he had played with great applause for many years. "

Handel's relationship with his star Senesino had never been happy, although they appreciated each other's artistic skills. This situation was not made any easier by the fact that Handel increasingly embarked on a new path with the English oratorio. Singing in English was a problem for Senesino, and the new roles gave him significantly fewer opportunities to show off his considerable vocal skills.

It wouldn't be a surprise if the Orlando himself contributed to the break with Senesino. The many unusual and innovative traits of opera could have confused or even unsettled a singer who had enjoyed the fame of the opera stage for 25 years and was deeply rooted in the conventions of the opera seria . A total of only three complete da capo arias were planned for him, none of them in the last act; his only duet with the leading soprano was short and formally very unusual; and he was not allowed to take part in the most important ensemble number, the trio at the end of the first act. In the great "mad scene" at the end of the second act he had the stage to himself for almost ten minutes, but the music gave him little opportunity for vocal ornamentation. Moreover, here and elsewhere in the opera, he may have been unsure whether he was playing a serious heroic or a subtly comical role, and if the latter was the case, the singer or the operatic character should be ridiculed.

As early as January 1733, some of Handel's rivals were planning to break his dominance at Italian opera in London:

"There is a spirit got up against the Dominion of Mr. Handel, a subscription carry'd on, and Directors chosen, who have contracted with Senesino, and have sent for Cuzzoni, and Farinelli [...]"

"A ghost arose against the dominance of Mr. Handel, subscriptions were given and directors were elected, they have already signed a contract with Senesino, and they are negotiating with Cuzzoni and Farinelli [...]"

The situation was made worse by Handel's plan to test the price of tickets to Deborah , even for those who had already paid a season ticket :

“Hendel thought, encouraged by the Princess Royal, it had merit enough to deserve a guinea, and the first time it was performed at that price […] there was but a 120 people in the house. The subscribers being refused unless they would pay a guinea, they, insisting upon the right of their silver tickets, forced into the House, and carried their point. "

“Handel thought, encouraged by the royal princess, [the performances] were established enough by now to ask for one more guinea and on the first evening with the new price […] there were just 120 people in the hall. The subscribers refused to pay an additional guinean and insisted on the right to their silver ticket, went into the opera house and defended their point of view. "

All of this increased animosity towards Handel's company and his audience began to look for alternative entertainment. On June 15, with the approval of Crown Prince Friedrich , Prince of Wales, several noble gentlemen met in open opposition to Handel to found a new opera company, the so-called "Opera of the Nobility". Through his open support for the aristocratic opera, the Crown Prince had transported the political feud between himself and his father, King George II , who had always supported Handel, to the music scene in London.

As a result of attempts by the aristocratic opera to entice away Handel's leading singers, with the exception of Anna Strada, who was the only one loyal to him and his prima donna until 1737, left at the end of the season. The rivalry between the two ensembles lasted for over three seasons, and although Handel eventually asserted himself, the experience clearly clouded his devotion to opera. Moving to John Rich's new Covent Garden Theater in 1734 inspired a significant and glorious opera season that premiered Ariodante and Alcina , among others .

libretto

The printed libretto names Samuel Humphreys as the author of the English translation of the opera text, but does not reveal the name of the lyricist of the Italian original - but neither does the name of the composer. Until the 1960s, Grazio Braccioli was repeatedly passed on from one publication to another as the author of the Orlando text set to music by Handel, although Joachim Eisenschmidt had already pointed out in 1940 that the text did not come from him, even if he did not make this claim and could not name any other librettist. As early as 1954, Edward Dent stated that the characters in Handel's libretto are completely different from those in Braccioli's Orlando libretti; and a comparison of Braccioli's texts with Handel's shows that the latter is a completely independent version. In addition, Handel's textbook also shows the layout typical of his later London operas with a significantly larger number of arias and a very concentrated, tightening treatment of the recitative texts. (Of the original 1,633 Rezitativzeilen just 632 remained, with the lion's share to two level games falls.) The assumption that Handel had worked even the recitatives of these operas herself or was at least involved in its recast, and the autograph of the seems to Orlando with to confirm his subsequent changes (deletions or abbreviations) of the text or the final scene of the second act and the Orlando / Dorinda dialogue in the third act (third scene). Eisenschmidt might rightly suspect that Handel's libretti were not edited by a writer, not even by an Italian. In any case, the unknown author provided Handel with a pretty good textbook, which inspired him to compose one of his best operas, and the shift between comedy and heroism in Orlando gives it a special place among Handel's operas.

This goes back to the main source of the libretto, namely Orlando furioso by Ludovico Ariosto (1474–1533), an epic describing the adventures of the Breton knight Roland ( Hruotland ) and the terrible frenzy into which he fell through his unrequited love for the Chinese princess Angelica device. All of this is impressively enriched with the fates of numerous other characters and a lot of casual commentary about human nature. Angelica, to the annoyance of her noble suitors, finally gives preference to the young African soldier Medoro (who is elevated to the rank of prince in the opera).

As a direct model, however, Handel used an older opera libretto by Carlo Sigismondo Capece (1652–1728) entitled L'Orlando, overo La gelosa pazzia (“Orlando, or the maddening jealousy”), set to music by Domenico Scarlatti and performed in Rome in 1711 was (the music has not been preserved). The version that Capece and an unknown editor Handel gave to the intricate material about the maddening, maddening knight assumes that the viewer knows about the legend. The prehistory of Orlando and Angelica is only hinted at, instead the focus is on the hero's pioneering madness. The figure of the magician Zoroastro, which was only added to Handel's libretto, turns the knight's adventure journey around beautiful virgins in need and challenging battles against rival paladins into a search for one's own self. With the decision of the Chinese princess for the enemy Medoro, Orlando's world of knights collapses with all its laws, which according to Angelica should have fallen to him. This process of dissolution continues in the figure itself: with his mind he loses his own ego, which he only regains through the healing of Zoroastro. Freed not only from madness, but also from distracting love, Orlando can then, in the sense of reason - the name derived from Zoroastros from " Zarathustra " (Italian: "Sarastro") - as a purified knight his life again Mars, the God of war, dedicate.

Capece's original text had to be changed significantly to make it suitable for Handel's troop. The roles of Orlando, Angelica and Medoro were not a problem: The title role naturally went to Senesino, that of Angelica to the soprano Anna Strada del Pò and that of Medoro to the reliable alto Francesca Bertolli, whose specialty were male roles. The semi-comical figure of Dorinda was ideally suited for the soubrette Celeste Gismondi, who had recently joined Handel's ensemble and whose skills may have influenced the choice of libretto. She is most likely identical with Celeste Resse, called "La Celestina", a versatile singer who had taken on countless roles in the intermezzi performed there in Naples between 1724 and 1732. Her part in the opera has been considerably expanded compared to Capeces original. The most drastic revision of the template was necessary to create an appropriate part for the great bassist Antonio Montagnana. Capece had planned an important subplot with royal lovers: Princess Isabella and the young Scottish Prince Zerbino; but it was not common then for a bass to play the role of a young prince. Therefore, Isabella and Zerbino were practically completely deleted and the remarkable magician figure of Zoroastro for Montagnana was added. However, Isabella remains in the opera as a silent presence: she is the mysterious princess who is saved by Orlando in the first act.

These changes had a profound effect on the tone of the opera. They gave special weight to the shepherdess Dorinda and made her almost a tragic figure. (She is the only low-born woman in Handel's operas and it is not surprising that he gave her a special musical character.) They also presented Orlando's madness in a new context, no longer as a direct result of his jealous obsessions, but as a wholesome frenzy, which is planned and imposed by Zoroastro to clear the hero's consciousness. From the kaleidoscopic confusion of Ariostus, which in its multitude of stories and interpretations always proclaims the ideal of high love, Handel draws the moral interpretation typical of the baroque drama, which foresees the enlightenment theory of the victory of the understanding over passion. And even if the paladin, who finally recovered, was unable to save Handel's Royal Academy of Music, he still united the great singers of his time one last time.

After ten performances under Handel's direction in 1733, Orlando was performed for the first time again under the title Orlandos Liebeswahn at the Handel Festival in Halle (Saale) on May 28, 1922 in an arrangement by Hans Joachim Moser in German and under the direction of Oskar Braun. The first performance in the original language and historical performance practice was on February 25, 1983 during the Washington University Baroque Festival at the Edison Theater in St. Louis , Missouri, with an orchestra composed of the Collegium Musicum of Washington University and the Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra ( Toronto ) directed by Nicholas McGegan .

action

Historical and literary background

As "noto quasi ad ognuno" ("almost everyone known") describes the libretto in the "Argomento" ("Preliminary remark") Ludovico Ariostos Orlando furioso , which was printed as early as 1732 - the verse epic published for the first time in 1516, which is once again the old French from the end of Continued the 11th century Roland song. The historical background of the Roland saga is the campaign of Charlemagne against the Saracens in Spain, which came to a bloody end in the battle of Roncesvalles in 778. Soon after this battle, in which the entire Frankish army was destroyed and numerous high dignitaries were killed, a legend began to emerge about Count Hruotland, the fallen governor of the Breton march . Ariostos Orlando furioso expanded the Roland saga not only with a colorful heap of mythical creatures and invented people and stories, but also with the mania for love of the noble paladin , who goes mad out of unrequited love for Angelica, Queen of China. In contrast to Ariodante and Alcina , who each single out individual episodes from Ariostos Orlando furioso , Handel's Orlando refers to the basic theme of the literary original, without any coherent text excerpts being named as a model. The set pieces can be found in chants 12, 13, 18, 19, 23, 29, 34 and 39. Dorinda is an invention of the librettist, and Zoroastro is mentioned only once in Ariosto - in the 5th stanza of the 31st song, where jealousy is described as a poisonous wound that even the magical powers of Zoroastro would not be able to heal.

That “Argomento” sums up the theme and plot of Handel's opera very nicely as follows: “The unbridled passion that Orlando feels for Angelica, the Queen of Catai, and which ultimately completely robs him of his senses, is an event taken from Ariost's incomparable poetry which is so well known that it may serve here to indicate the content of this new drama without further explanation. The shepherdess Dorinda's invented love for Medoro and the magician Zoroastro's constant zeal for the honor of Orlando are supposed to show the violent way in which love lets its power work on the hearts of people of all classes, and just like a wise man with his at any time best efforts should be ready to lead back on the right path those who have been led astray by the illusion of their passions. "

first act

At night in the country . Zoroastro watches the movements of the planets and ponders how mysterious they are to the human mind. He believes he realizes that the hero Orlando will do glorious deeds again. Orlando appears, excited by love and fame in equal measure, and is urged by Zoroastro to forget love and Cupid and follow Mars, the god of war ( Lascia Amor, e siegui Marte , no. 4). Orlando is inclined to admit the reproach ( Imagini funeste , No. 5), but remembers that Hercules and Achilles did not soften either when they devoted themselves to women ( Non fu già men forte , No. 6).

A grove with shepherds' huts . Dorinda remembers the pleasures that nature with its beauties has always given her, but now feels filled with restlessness, which she interprets as being in love ( Quanto diletto avea tra questi boschi , No. 7). Orlando appears with a princess whom he has just saved, but immediately disappears again ( Itene pur Fremdendo , No. 8). Dorinda thinks that he too lives for love and reflects on her own insecurity ( Ho un certo rossore , no. 9).

Angelica confesses to herself that she fell in love with Medoro while tending to his wounds ( Ritornava al suo bel viso , no.10 ). Medoro, who initially listened to her apart, declares his love for her, but does not feel worthy of her. She asserts that someone who possesses her heart may also call himself king ( Chi possessore è del mio core , no. 11).

Dorinda has discovered that it is Medoro she has fallen in love with. Apparently he has passed Angelica as his relative in order not to disappoint her. Now he assures her that he will never forget her ( Se il cor mai ti dirà , No. 12). She knows that he is lying, and yet she is fooled by his words and looks ( O care parolette , no. 13).

Zoroastro accuses Angelica of her love for Medoro and warns her of the revenge of Orlando's, to which she is indebted. Angelica, waiting for Medoro, with whom she wants to leave, meets Orlando and is jealous of the princess he has saved. He protests that he only loves Angelica, whereupon she admonishes him to prove his loyalty ( Se fedel vuoi ch'io ti creda , no. 14). Orlando declares that he wants to fight monsters and giants to prove his love ( Fammi combattere , no.15 ).

Medoro wants to know who Angelica was talking to. She says it was Orlando and warns him not to mess with such a rival. As they embrace goodbye, Dorinda joins them and realizes their disappointment. She is comforted by Angelica and Medoro ( Consolati o bella , no. 16).

Second act

In a forest . Dorinda thinks that the nightingale's song is a suitable background for the pain of her love ( Quando spieghi i tuoi tormenti , no. 17). Orlando appears and asks her why she is telling people that Orlando loves Isabella. She replies that she spoke of Angelica, who has now left with her lover Medoro. Dorinda explains that she also loves Medoro and that she received a jewel from him (Angelica actually gave it to her). Orlando recognizes the bracelet he gave Angelica and concludes that Angelica has betrayed him. Dorinda tells him that Medoro is his rival, whom she sees in every flower and who is present for her in every natural phenomenon ( Se mi rivolgo al prato , no. 18). Orlando is angry: he wants to pursue Angelica down to the underworld and even kill himself for it ( Cielo! Se tu il consenti , no. 19).

An area with laurel trees on one side and a grotto on the other . Zoroastro warns Angelica and Medoro of Orlando's revenge. He promises to help them escape and explains that our minds wander around in fog when guided by a blind God and not by reason ( Tra caligini profonde , no. 20).

Angelica asks Medoro to saddle the horses while she waits. Medoro carves their names in a tree and leaves ( Verdi allori, semper unito , no. 21). Angelica realizes that she has shown herself ungrateful to Orlando, who saved her life. But she could not defend herself against Cupid's arrow ( Non potrà dirmi ingrata , no. 22).

Orlando is looking for the lovers and finds their names carved into the tree bark. He enters the grotto to look for her there.

Angelica says goodbye to the charms of nature ( Verdi piante, erbette liete , no. 23). Orlando reappears and she escapes. Medoro sees them both and follows them. When Angelica steps back on the scene, she is surrounded by a cloud and carried into the air by four geniuses. Orlando is now insane. As a shadow, he wants to go to the underworld to pursue Angelica. He hears the hellhound Cerberus yapping and sees Medoro in the arms of Proserpina ( Ah! Stigie larve!, No. 24). He wants to snatch it from her, but is initially touched by Proserpina's crying, but then flares up again in anger ( vaghe pupil ). He runs into the grotto, which is falling apart. Zoroastro drives off into the air in his car with Orlando in his arms.

Third act

A place with palm trees. Medoro has returned to Dorinda's house at Angelica's request. She offers him to hide there, but he lets her understand that he cannot love her ( Vorrei poterti amar , no. 26). Dorinda is glad he's telling the truth now.

Orlando meets Dorinda and declares his love for her ( Unisca amor in noi , no. 27). Dorinda would like to go into this, but is confused. Eventually it turns out that Orlando is still delusional: he sees in her Argalia, the brother of his lover, who was killed by Ferrauto. He fights himself with the imaginary Ferrauto ( Già lo stringo, già l'abbraccio , No. 28).

Angelica comes to Dorinda and learns that Orlando has gone mad. She feels sorry, but hopes that he will defeat himself ( Così giusta è questa speme , no. 29). Dorinda stays behind and describes love as a wind that, in addition to brief pleasure, brings long mourning ( Amor è qual vento , No. 30).

Zoroastro explains to Orlando as an example that the lover often goes insane. He turns the grove into a cave and wants to cure the hero from madness ( Sorge infausta una procella , no. 32).

Meanwhile, Dorinda Angelica reports that Orlando destroyed her home and buried Medoro under the rubble. She goes out and Orlando comes over. He thinks Angelica is Falerina and wants to kill her. Angelica can no longer mourn her own fate because she weeps over Medoro ( Finché prendi ancora il sangue , no.33 ). Orlando takes it and throws it - as he believes - into the abyss, actually into a cave that turns into a temple of Mars. He falls asleep ( Già l'ebro mio ciglio , No. 35).

Now Zoroastro's time has come: from heaven he asks for a drink to heal Orlando ( Tu, che del gran tonante , No. 36). An eagle brings a vase, which Zoroastro pours on Orlando's face. Orlando wakes up and is ashamed that he killed Angelica and Medoro. He wants to throw himself into the abyss ( Per far, mia diletta , No. 38), but is stopped by Angelica. Zoroastro saved her and Medoro. There is reconciliation, and Orlando is proud to have triumphed over himself and love ( Vinse in canti, battaglie , no. 39). The quintet forms the final chorus ( Trionfa oggi'l mio cor , No. 40).

Ariost's poetry as an operatic subject

|

Le donne, i cavallier, l'arme, gli amori, |

I sing to you of women, of knights and battles, of

noble custom, |

This is how Ludovico Ariosto begins his verse epic Orlando furioso . But the times when Charlemagne's Frankish empire was threatened by the Saracens and a pagan army was about to overrun the Christian Occident are only the starting point for much more confused and fantastic stories.

Orlando fights a completely different nature - he sharpens his saber on the battlefield of love. The paladin is in love with Angelica, the beautiful Chinese princess from the distant realm of the Great Khan of Cathay . She once came to the Frankish Empire to beguile the best knights in Paris and kidnap them to defend their home castle Albracca . Orlando followed her to Cathay, fought for her and granted all her wishes. Then she accompanied him back to the Franconian Empire. However, since she did not want to be a bargaining chip for love, she finally gave herself up to none of the famous Christian paladins, but to one of the pagan conquerors, the Saracen warrior Medoro.

This is just one of the innumerable storylines from Ariostos Orlando furioso . The poet has interwoven Arabia, Jerusalem, Paris, the moon and finally the sky as constantly changing scenes into a magical cosmos. Historical threads of action from antiquity to the Renaissance are connected with sagas and legends of many mythologies. Everything goes back to Hruodlandus, the margrave and paladin of Charlemagne, who, according to tradition, fell in the battle against the Moors in 778. Arab sources report that the Saracens took part in the fight at that time, from which Ariosto and his predecessors created the overpowering enemies of the Franks, who invaded the kingdom of the Franks as revenge for the death of their great king Trojan from Spain and Africa. Orlando, the fictional nephew of Charlemagne, appeared as the embodiment of warlike heroism in the early Middle Ages. Starting in France, where the oldest Roland epic Chanson de Roland had its origin, the heroic deeds of the brave paladin were soon sung all over Europe.

Not only Italy and Spain, but also England and Germany claimed Roland as national heroes and dedicated epics, romances, poems and dramas to him since the 13th century. With the change of literary taste, the character of this often-told saga experienced drastic changes over time. The once bloody heroic epic gradually turned into a colorful tale in which love affairs, depictions of errant knighthood and powerful magicians intertwine. Even before Ariosto, the Italian Renaissance poet Matteo Boiardo placed the erotic element in the foreground in his Orlando innamorato . The "amorous Roland" no longer goes to war against all sorts of magical things for the emperor and fatherland, but fights for the flirtatious Angelica, the "angelic" one. When the war against the pagans ordered him back home from afar in Albracca, he allowed himself to be distracted more and more from his knighthood by potential competitors in courting for Angelica's heart, until Charlemagne at some point saw the measure of the bearable and the lovely princess saw him promises who will do best in combat. At this point Boiardo's story breaks off and is only continued with Ariosto, who makes the title hero lose his mind because of the unfulfilled love for Angelica. Begun in 1504, published for the first time in 1516 and the final version appeared in 1532 after years of constant revision, Ariosto tells a fairy tale in the form of a motley pasticcios in which, in addition to magicians, fairies and monsters, above all the argumentative, adventurous and love-addicted people of his own time Play the main role. The poet himself reveals his recipe for success when he says that he does not want to cherish heroes or proclaim everlasting truths, but rather write for amusement and relaxation. His Orlando is anything but a true hero. Cupid's arrows care and bend the once brave paladin far more than the scimitar of the Saracens. The unfulfilled love for Angelica robs him of his mind, he is downright out of his mind:

|

Sì come quel ch'ha nel cuor tanto fuoco, First chant |

The love whose sweet compulsion Schiller |

Such a confusion about love, jealousy, intrigue and the arts of magic offered attractive subjects for the opera genre. So it is hardly surprising that this material was used in opera literature of the 18th century alongside the usual subjects that come from Greek or Roman antiquity.

music

For Handel, what was so appealing about the new version of the libretto was that it offered him the framework for music of far greater diversity and formal flexibility than could be accommodated in a conventionally structured opera seria . The first act begins with Zoroastro looking up at the sky and reading Orlando's Fate in the stars. He performs the first of many extensive Accompagnato recitatives that are a salient feature of this opera. A series of short songs without da capo repetition are also striking . The first, Angelica's Ritornava al suo bel viso (No. 10), is happily and unexpectedly continued by Medoro when he appears to greet her. In the third act, Orlando sings the unforgettable Già l'ebro mio ciglio (No. 35) after a burst of anger , before sinking into the healing sleep brought about by Zoroastro. The accompaniment here consists of two “Violette marine con Violoncelli pizzicati”, for the two Castrucci brothers, “per gli Signori Castrucci”, as Handel expressly notes in his manuscript.

Pietro Castrucci was the leading violinist in the opera orchestra. Because the instrument he invented has been forgotten, we can only infer its quality from its name and Handel's music. The small viola, called the violetta, was in use at the time and is also used by Handel, but never as a solo instrument such as the violin or the cello. The two “Violette marine”, on the other hand, only appear solo, in an independent two-part movement, which is only joined by a delicate violoncello bass when the singing begins. Whether Castrucci named his instrument after the old "Tromba marina" and what meaning he associated with the epithet "marina" will probably always remain unclear. But one thing is certain: his “violetta marina” was a small viola with additional sympathetic strings that gave the instrument's veiled sound more fullness. It was suitable for solo performance, perhaps only usable in this way because of its delicacy, and had the range of an ordinary viola. In Handel's sentence, the upper “violetta marina” reaches the double-slashed “es” in height, the lower one with the lower case “e”.

And finally, Per far, mia diletta (No. 38), which Orlando reads when he thinks of suicide. Pure unison of the strings in an impressively dotted rhythm dominates the accompaniment; but the most beautiful and simplest effect leaves us waiting until the end: the last cadenza, for figured bass alone, is continued by an ascending phrase Angelica in the parallel key when she begs Orlando to go on. Of course there are also several school-style arias, all of high quality, as well as some good ensemble numbers. In the beautiful, moving trio at the end of the first act, Angelica and Medoro try to calm Dorinda when she realizes that her love for Medoro must remain unfulfilled and is heartbroken about it. The music, which starts from a deceptively simple G major melody in three time, nevertheless expresses an unusual depth of feeling. There are two decidedly unconventional duets in the third act. In the first, the desperate Orlando begins to woo Dorinda with a delicate tune in a minor key; she initially replies with faster music in a straight beat, but soon turns exclusively into recitative. Orlando sees himself caused to rage, he wants to fight the warrior Ferraù (one of his rivals for Angelica's favor in Orlando furioso ). He does this with the short but unusual aria Già lo stringo, già l'abbraccio (No. 28), the main part of which is a parody of a gavotte and the middle section of which is a slow arioso passage that changes to the remote key of A flat minor . Finchè prendi ancora il sangue (No. 33), Orlando's duet with Angelica, is another remarkable piece that gives the impression that it has two alternating tempos, one for each performer, although the basic rhythm remains constant.

The scene that closes the second act shows the most astonishing musical course of this opera - if not of all baroque operas. Beside himself, because he finds the names Angelica and Medoro carved into the bark of the trees, Orlando succumbs to the delusion that he is on a journey to the underworld. The music begins as an Accompagnato recitative, first lively, then more slowly, with unclearly demarcated, changing harmonies, while Orlando describes himself as "my own, secluded spirit". There are short passages in 5/8 time, played in unison by the strings, when he imagines he is climbing Charon's boat and crossing the Styx . The conclusion is a rondo on an unadorned, but very touching melody in F major in the Gavotte rhythm, the execution of which is separated by two episodes each about three times as long. The first is a Passacaglia in 3/4 time and D minor in Larghetto tempo. It is based on a 4-bar, chromatically descending fourth in the bass, a passus duriusculus , which has been known since the Renaissance as an expression of pain and suffering. This tone sequence is repeated an octave lower, which underlines the downward movement. Then this 8-bar group is repeated three times as ostinato , on which Orlando varies his depiction of suffering, so that the Passacaglia emerges. The chromatic bass passage was certainly intended as an allusion to the traditional lamentations of opera in the 17th century (such as in Dido and Aeneas ). The other episode marks Orlando's transition to a vengeful mood and is dominated by fast, furious violin playing. Handel's achievement in this scene, as elsewhere in the opera, is to create a feeling of disorder and chaos, and to do so with music, which by its very nature must be strongly structured. He does it by juxtaposing ideas that are often different in tempo and rhythm (3/4 and 4/4 time alternate) but are held together by infallible control of the underlying harmonic progression.

The opera as a whole has a sense of disquiet that is not completely dispelled by the lively character of the final chorus (Dorinda's little solo remains in the minor key and is broken down by manically choppy rhythms). If Orlando had been a reason that Handel's singers decided to leave him and join a new opera company, since they felt that he was leading the opera into frightening, untapped waters, they probably did not go entirely wrong with their judgment.

Success and criticism

“Such as are not acquainted with the personal character of Handel, will wonder at his seeming temerity, in continuing so long an opposition which tended but to impoverish him; but he was a man of a firm and intrepid spirit, no way a slave to the passion of avarice, and would have gone greater lengths than he did, rather than submit to those whom he had ever looked on as his inferiors: but though his ill success for a series of years had not affected his spirit, there is reason to believe that his genius was in some degree damped by it; for whereas of his earlier operas, that is to say, those composed by him between the years 1710 and 1728, the merits are so great, that few are able to say which is to be preferred; those composed after that period have so little to recommend them, that few would take them for the work of the same author. In the former class are Radamistus, Otho, Tamerlane, Rodelinda, Alexander, and Admetus, in either of which scarcely an indifferent air occurs; whereas in Parthenope, Porus, Sosarmes, Orlando, Ætius, Ariadne, and the rest down to 1736, it is a matter of some difficulty to find a good one. "

“Anyone who does not know Handel's personality will be amazed at the apparent recklessness with which he waged such a persistent struggle that ultimately only threw him into ruin; but he was a man of imperturbable and fearless disposition, in no way succumbed to the vice of avarice, and would have taken upon himself even more than actually the case in order not to surrender to those whom he considered inferior to him: although his Years of failure did not burden him externally, there is reason to believe that his creative power was in some way impaired; because while his earlier operas, which means those he composed between 1710 and 1728, are so successful that hardly anyone can say which of them is preferable, little speaks in favor of the operas of the later years, so few would recognize in them the work of one and the same composer. The former include Radamistus, Otho, Tamerlane, Rodelinda, Alexander and Admetus; they all contain hardly a single uninteresting piece; on the other hand it is difficult to find a single good melody in Parthenope, Porus, Sosarmes, Orlando, Ætius, Ariadne and the remaining operas written up to 1736. "

Orlando was the last opera in which Handel composed songs expressly for Senesino; [...] but by a comparison of the songs intended for Senesino, after the opera of Porus , with those which Handel had composed for him previous to that period, there seems a manifest inferiority in design, invention, grace, elegance, and every captivating prop.

“ Orlando was the last opera in which Handel composed arias especially for Senesino; […] But when comparing the chants intended for Senesino one finds that after the opera Poros there is a noticeably lower quality of the concept, less ingenuity, grace, elegance and less interesting equipment. "

“The greatest peculiarity of this opera is, in any case, the aforementioned final scene of the second act, consisting of several recitative and arioso movements in which a joyful, significant melody asserts itself, which also breaks through victoriously towards the end. According to its form, that would be a completely modern opera finale without a choir, akin to a Weberian tone painting, and this scene could be performed as it stands now without the listeners even remotely suspecting a Handelian origin: so little does it fit into the terms that have been accepted as authoritative for Handel's art. "

"With right of Handel biographer Hugo Leichtentritt to Orlando , considered one of the strongest and richest Handel's operas'. Scenic variety, very dramatic treatment of the material and excellent character drawing are combined with an almost immeasurable wealth of wonderful melodies and valuable musical ideas. "

“It is disconcerting to find eighteenth-century opinion, particularly when it is expressed by two men who were acquainted with Handel, so different from our own. Perhaps it should be taken as fair warning against passing judgment on opera from the printed page, although Burney's description of Orlando shows that he at least consulted the manuscript, not merely the Walsh edition. The same opera, to modem eyes after the experience of twentieth-century revivals, is' one of Handel's richest and most rewarding operas' (Andrew Porter, The New Yorker , 14 March 1983) and to Winton Dean a 'masterpiece […] musically the richest of all his operas' ( Handel and the Opera Seria , p. 91), comparable on several counts with The Magic Flute . [...]

It was chiefly their concentration on set pieces that makes the commentaries of both Burney and Hawkins on Handel's later operas defective. Opera seria originated in the word-book, and a study of this reveals levels of the composer's creative intentions which escaped them: the 'Argument', the allocation of arioso and accompanied recitative in place of secco (for an increase in intensity that did not imply an obligatory exit for the character), the introduction of symphony and above all, the consistent development of a psychological thread and the exploitation (rather than simply the creation) of situations. "

“It is downright disturbing how much the eighteenth-century views were expressed by two men who were familiar with Handel [Burney and Hawkins, p. o.] differ from ours. We can perhaps learn from this fact that an opera cannot be judged on the basis of the print; however, Burney's description of the Orlando shows that he at least consulted the manuscript, not just the Walsh edition . After its revival in the twentieth century, the same opera is now considered to be 'one of Handel's most magnificent and worth seeing operas'. And for Winton Dean it is 'a masterpiece [...] musically the most splendid of all Handel operas,' in some ways comparable to the Magic Flute . [...]

What makes both Burney and Hawkins' comments so inadequate is the fact that both focused only on the pieces being set to music. The Opera seria was created on the basis of a text book; If you take a closer look at this, you can see many of the composer's creative moments that the two historians missed: the thematization, the use of arioso and accompanying recitative instead of secco (whereby an increase in intensity was achieved that does not necessarily mean that the respective Figure), the introduction of orchestral preludes, the coherent knotting of a psychological thread and the exploitation (not the simple invention) of situations. "

orchestra

Two recorders , two oboes , bassoon , two horns , two violets, strings, basso continuo (violoncello, lute, harpsichord).

Discography (selection)

- Oriel Music Society 085/3 M (1963): Guy Baker (Orlando), April Cantelo (Angelica), Pamela Bowden (Medoro), Heather Harper (Dorinda), Stanislav Pieczora (Zoroastro)

- Mondo Musica 10502 (1985): Marilyn Horne (Orlando), Lella Cuberli (Angelica), Jeffrey Gall (Medoro), Adelina Scarabelli (Dorinda), Giorgio Surjan (Zoroastro)

- Orchestra of the Teatro La Fenice ; Gov. Charles Mackerras

- L'Oiseau-Lyre 430 845-2 (1991): James Thomas Bowman (Orlando), Arleen Augér (Angelica), Catherine Robbin (Medoro), Emma Kirkby (Dorinda), David Thomas (Zoroastro)

- The Academy of Ancient Music ; Dir. Christopher Hogwood (158 min)

- Erato 0630-14363-2 (1996): Patricia Bardon (Orlando), Rosemary Joshua (Angelica), Hilary Summers (Medoro), Rosa Mannion (Dorinda), Harry van der Kamp (Zoroastro)

- Les Arts Florissants ; Dir. William Christie (169 min)

- Arthaus 101 309 (2007): Marijana Mijanović (Orlando), Martina Janková (Angelica), Katharina Peetz (Medoro), Christina Clark (Dorinda), Konstantin Wolff (Zoroastro)

- “ La Scintilla ” orchestra of the Zurich Opera House ; Dir. William Christie (DVD)

- K617 (2010): Christophe Dumaux (Orlando), Elena de la Merced (Angelica), Jean-Michel Fumas (Medoro), Rachel Nicholls (Dorinda), Alain Buet (Zoroastro)

literature

- Winton Dean : Handel's Operas, 1726-1741. Boydell & Brewer, London 2006. Reprint: The Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2009, ISBN 978-1-84383-268-3 (English).

- Silke Leopold : Handel. The operas. Bärenreiter-Verlag , Kassel 2009, ISBN 978-3-7618-1991-3 .

- Arnold Jacobshagen (ed.), Panja Mücke: The Handel Handbook in 6 volumes. Handel's operas. Volume 2. Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2009, ISBN 3-89007-686-6 .

- Bernd Baselt : Thematic-systematic directory. Stage works. In: Walter Eisen (Ed.): Handel Handbook: Volume 1. Deutscher Verlag für Musik , Leipzig 1978, ISBN 3-7618-0610-8 (Unchanged reprint, Kassel 2008, ISBN 978-3-7618-0610-4 ) .

- Christopher Hogwood : Georg Friedrich Handel. A biography (= Insel-Taschenbuch 2655). Translated from the English by Bettina Obrecht. Insel Verlag , Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 2000, ISBN 3-458-34355-5 .

- Paul Henry Lang : Georg Friedrich Handel. His life, his style and his position in English intellectual and cultural life. Bärenreiter-Verlag , Basel 1979, ISBN 3-7618-0567-5 .

- Albert Scheibler: All 53 stage works by Georg Friedrich Handel, opera guide. Edition Cologne, Lohmar / Rheinland 1995, ISBN 3-928010-05-0 .

- Friedrich Chrysander : GF Handel. Second volume. Breitkopf & Härtel , Leipzig 1860.

- Anthony Hicks: Trade. Orlando. L'Oiseau-Lyre 430 845-2, London 19911.

- Siegfried Flesch : Orlando. Preface to the Halle Handel Edition II / 28. German publishing house for music , Leipzig 1969.

- handelhouse.org

Web links

- Score by Orlando (Handel work edition, edited by Friedrich Chrysander , Leipzig 1881)

- Orlando : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Libretto (PDF; 337 kB) by Orlando

- Action by Orlando (Handel) on Opera-Guide landing page due to URL change currently not available

- Burney over Orlando

- Additional information on Orlando

- Action and background of Orlando (English)

- Video clip of the Semperoper , January 2013, Dresden

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Anthony Hicks: Handel. Orlando. L'Oiseau-Lyre 430 845-2, London 1991, p. 30 ff.

- ^ Victor Schœlcher: The Life of Handel. London 1857, p. 122.

- ^ A b c Siegfried Flesch: Orlando. Preface to the Halle Handel Edition II / 28. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1969, p. VI ff.

- ↑ a b Edition management of the Halle Handel Edition: Documents on life and work. In: Walter Eisen (Ed.): Handel Handbook: Volume 4. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1985, ISBN 3-7618-0717-1 , p. 208.

- ↑ Winton Dean: Handel's Operas, 1726-1741. Boydell & Brewer, London 2006, Reprint: The Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2009, ISBN 978-1-84383-268-3 , p. 252.

- ↑ a b Handel Reference Database . ichriss.ccarh.org. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ↑ a b Christopher Hogwood: Georg Friedrich Handel. A biography (= Insel-Taschenbuch 2655). Translated from the English by Bettina Obrecht. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 2000, ISBN 3-458-34355-5 , p. 186 ff.

- ↑ a b c Orlando. Handel House Museum . handelhouse.org. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ^ Editing management of the Halle Handel Edition: Documents on life and work. In: Walter Eisen (Ed.): Handel Handbook: Volume 4. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1985, ISBN 3-7618-0717-1 , p. 211.

- ↑ a b c d e f Nora Schmid: Orlando. On the battlefield of love. Program booklet, Sächsische Staatstheater - Semperoper, Dresden 2013, p. 7 ff.

- ^ Silke Leopold: Handel. The operas. Bärenreiter-Verlag, Kassel 2009, ISBN 978-3-7618-1991-3 , p. 143.

- ^ Silke Leopold: Handel. The operas. Bärenreiter-Verlag, Kassel 2009, ISBN 978-3-7618-1991-3 , pp. 259 f.

- ↑ a b Orlando_furioso / Canto 1 on Wikisource

- ↑ a b Friedrich Schiller : Ariosts raging Roland .

- ↑ a b c Friedrich Chrysander: GF Handel. Second volume. Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 1860, p. 253 ff.

- ↑ Sir John Hawkins: A General History of the Science and Practice of Music. London 1776, new edition 1963, Vol. II, p. 878.

- ↑ A General History of the Science and Practice of Music . archive.org. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ^ Charles Burney: A general history of music: ... Vol. 4. London 1789, p. 367.

- ^ Hans-Gerald Otto: Orlando. Program booklet Landestheater Halle, 1961.

- ^ Andrew Porter: Musical Events: Magical Opera. In: The New Yorker , March 14, 1983, pp. 136 f.

- ^ Winton Dean: Handel and the Opera Seria. Oxford University Press, 1970, ISBN 0-19-315217-7 , p. 91.

- ↑ Christopher Hogwood: Commerce. Thames and Hudson, London 1984, Paperback Edition 1988, ISBN 0-500-27498-3 , pp. 101 f.