The transformed Daphne

| Work data | |

|---|---|

| Original title: | The transformed Daphne |

|

|

| Shape: | early German baroque opera |

| Original language: | German Italian |

| Music: | georg Friedrich Handel |

| Libretto : | Hinrich Hinsch |

| Premiere: | January 1708 |

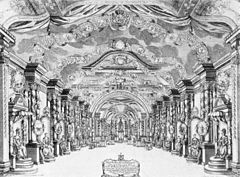

| Place of premiere: | Theater am Gänsemarkt , Hamburg |

| Place and time of the action: | mythical time and place ( Thessaly , 6th century BC) |

| people | |

|

|

The transformed Daphne ( HWV 4) is Georg Friedrich Handel's fourth opera and his last in German. After that he composed only one full-length work in his mother tongue: the Brockes Passion (1716). All of Handel's operas written later are in Italian and are of the type Opere serie . Daphne's score is lost. Individual sentences could be identified in collections of individual works.

Creation & libretto

The double opera Florindo and Daphne (in Hamburg the operas were always announced as a Singspiel ) was written in the spring of 1706, still on behalf of Reinhard Keiser . However, the work was not performed at this time. Political turbulence and the change of tenant at the Gänsemarkt-Theater meant that the operas were only included in the program in January 1708 under the direction of Johann Heinrich Sauerbrey, who had taken over the opera business together with the singer Johann Konrad Dreyer and the consul Reinhold Brockelmann . The old management, consisting of Keizer and the dramaturge Drüsicke, had to give up in September 1706. There are contradicting views as to whether the operas The happy Florindo and The Metamorphosed Daphne were originally intended for one evening and then split over two evenings because of excess length, or whether the system provided for two separate sections from the outset, i.e. two operas with three acts each . The preface to the libretto of Florindo (see below) suggests the first case, but there are some doubts about it: The Handel researcher Friedrich Chrysander interpreted the comment in the preface that the music "fell too long" in such a way that Handel worked out too much and wrote arias for too long. However, the libretto shows concentrated, often short arias and ensembles. The 55 musical numbers to be set by Handel in the Florindo are the normal measure of a German opera at this time. The then 100 music numbers together with Daphne would not have been expected of the audience by the young but by no means inexperienced in theater in one evening. It can be assumed that the work was conceived from the outset, or at least after the completion of the libretto, to be given over two evenings. Such a procedure was quite common on the Hamburg stage. In the years 1701 and 1702 alone, three double operas by Reinhard Keizer with subjects about Störtebecker , Odysseus and Orpheus were performed. All of them were full-length, three-act works.

For his German adaptation of the material, the poet Hinrich Hinsch apparently used an Italian opera text as a template, but it has not yet been identified. What remains are several arias that were sung in the original language in the Hamburg performances. Hinsch had come into play because Handel's first librettist Friedrich Christian Feustking , the author of the texts on Almira and Nero (both 1705), was suspected of having had several love affairs and had to leave Hamburg.

After composing the double opera, Handel devoted himself only to teaching in Hamburg, studying the works of his colleagues (including making a complete copy of Keiser's Octavia , which he took with him to Italy), and preparing for his departure to Italy. He probably left Hamburg in the summer of 1706 and never heard his double opera. The musical direction of the premieres was most likely in the hands of Christoph Graupner , who was harpsichordist and conductor at the Hamburg Opera House from 1705 to 1709.

The first performance of Daphne in January 1708 was supplemented by an intermezzo in the Low German dialect: The funny wedding, and Bauren Masquerade employed there (text by Mauritz Cuno, music probably by Graupner and Keizer). At that time, Handel had already premiered his first Italian opera, Rodrigo , in Italy .

Cast of the premiere

- Daphne - Anna-Margaretha Conradi, called "Conradine" ( soprano ) (?)

- Florindo - Johann Konrad Dreyer ( tenor ) (?)

- further line-up: unknown.

action

Historical and literary background

In the first book of Metamorphoses Ovid tells the story of the nymph Daphne , who evades the intrusiveness of Phoebus ( Apollon ) by having her father transform her into a laurel tree. These two characters and Cupid come from the myth, all other characters in the operas are fictitious.

“The water of the Deucalionic Flood would have already fallen and the ground, dried by the sun's rays, would already have started to bring back all kinds of animals / as well as many herbs and flowers / as in Thessaly a great and immense dragon / called python / the mud of the earth was created / which infected the countryside with its poisonous breath / and corrupted the surrounding fields; Phœbus made himself at the same monster with his bow and arrows / killed them too happily / and freed the oppressed country from the dreaded destruction; Which then called / ordered a feast to this her Savior for his due gratitude / by the slain dragon Pythia / and therein worshiped the Phœbus for his good deed / with all imaginative testimonies of joy. Phœbus now became arrogant over this happy victory / that he despised Cupid's bow and arrow / against his weapons / and drew far for his victory over the dragon / of power / of love that only overcame soft and womanly hearts: what a shame then vindictive Cupid went so much to heart / that he took two arrows / one with a golden point / which ignited the heart it struck to a fervent love / and one with a bullet / which filled the wounded breast with bitter hate / took; With the first arrow he struck Phœbus's chest / and inflamed it with a violent heat against Daphne, the very beautiful daughter of Pineus, the god of water, / and thereby aroused in her an insatiable desire / to connect with this lovable nymph; But the same was struck by Bley's arrow / and not only felt no inclination to the Phœbus because of this, but rather fled its presence / and could not be moved to some counter-attunement either by flattery / by promise /. But when Phœbus was tormented by the passionate desire / his ardent desires / daily tormented / he hurried after the fugitive Daphne in a forest / and tried to bring her to his palace by force / had also overtaken the same near / as the terrified / and in utter desperation the nymph / cried to her father Pineus for assistance and salvation / who did not deny her his help / specially transformed her into a laurel tree. How Phœbus saw his purpose as a result / and the beautiful booty / which he thought he had already caught / was suddenly stolen from his hands again; Nevertheless, love did not want to give up its tender heart / he returned it to the transformed tree / and since he was used to making a crantz from any foliage / he chose the laurel tree to add to this ornament / and crowned it himself and his devoted admirers with laurel branches. This didactic and meaning poems described by Ovidius in his first book of Metamorphoses / gave us the opportunity to present a singing game / to embellish it with poetry / that Daphne, before Phœbus in you through Cupid's vengeance fallen in love / already connected with Florindo, son of the water god Enipheus / and plowed an alternating love: Florindo, on the other hand, was secretly loved generously by the noble nymph Alfirena / but cunningly sought by Lycoris; Lycoris, on the other hand, was so loved by Damon / that he lost his mind for a while / but afterwards / as he was fed with false hope from Lycoris at the beginning / but was subsequently amused with true counter-love / got it completely again; Like then also the generous Alfirena, like the Daphnen transformed / and the Florindo freed from his love and marriage vows / received the reward of their noble loyalty / and been connected to her Florindo. But because the excellent music with which this opera adorns / pleases a little too long / and wants to make the audience angry / has been considered necessary to divide the whole work into two parts; The first of these presents the feast of Pythia, which was held in honor of Apollo, and Florindo's betrothal to Daphne on the same day; and thus got the name of the happy FLORINDO, from this most noble act; The other part will represent the stubbornness of the Daphnees against Phœbus love / as well as their perceived disgust for all love / and finally their transformation into a laurel tree / and receive the name of the transformed DAPHNE. "

first act

The temple of hymen (god of marriage) is lit with burning candles. The nymph Daphne in bridal jewelry and Florindo, son of the river god Enipheus, wreathed with flowers, go to the altar of the hymen to get married. While the priests are making offerings to the god, Cupid enters. He wounds Daphne with an arrow as intended. When the priest tries to put the bridal belt on her, Daphne pushes him back. She screams “Stop! From now on I don't want to indulge in love anymore. ” Alfirena and Florindo are horrified, even the reminder to reflect doesn't help. Florindo, the bridegroom, now alone, is stunned and feels like in a bad dream.

The nymph Lycoris, alone in the forest, is happy that heaven is now accommodating her wishes for a liaison with Florindo by confusing Daphne's senses. Now she thinks she will have an easy time with him. From a distance she sees Daphne and Phoebus (Apollo) running towards her. She hides quickly. And so she hears Daphne asking Phoebus to leave her alone.

Phoebus, who was left alone, philosophizes about the unfathomable nature of “women's hearts”. The Lycoris that joins him agrees. She tells Phoebus on the head that he loves Daphne and that you can read the same thing in her eyes. Finally, she advises him not to be put off by the resistance and offers her help.

The shepherd Damon and his trusted friend Tyrsis meet in the same place. Damon is extremely suspicious that something could happen between Lycoris and Phoebus. Tyrsis reassures him and assures that Lycoris is faithful.

Florindo longs for Daphne and insults the cruel forests that hide Daphne. He asks the wind and the leaves to tell him where they are. Alfirena, secretly in love with Florindo, sees how he runs after the discovered Daphne. She realizes that Florindo's powers are weakening. She ponders whether to help him, but hides behind a rock on which she scratches: “An eye you know; a heart unknown to you. ” Florindo approaches, he is disappointed that he cannot find anyone, but asks himself who left the soulful message from the rock. But he does not have the ability to interpret.

Cupid enters. He warns to despise love. He does not introduce himself and remains a handsome boy for those involved. Cupid explains what the inscription says and from whom it comes. So he believes he is luring Florindo away from Daphne in favor of Phoebus and towards Alfirena.

Second act

Florindo, who runs after Daphne and also reaches her, tries to bring her to reason. But she doesn't want to accept his love anymore. She destroys his hope because she wants to stay free and tells him that the goddess Diana has chosen her to enter her service. Now both are helpless and without a goal of thought or action. She wants to die with him, but not live with him.

The rural people and the priests of Pan prepare a forest service. Florindo pulls Daphne to the forest temple. At first she refuses, but then she follows. Cupid steps up and is - when he sees the two huddled together - shocked and angry about how powerless his love arrows were. His anger shatters Pan's house and furies rise from the earth. While they mingle with the dancers, Daphne and the others manage to escape. Florindo, however, is left alone. In the following encounter with Alfirena, he believes he will discover that she is the scribe of the rock script. Lycoris comes to Florindo when Alfirena has gone and woos him. Florindo is desperate because Daphne - who is desired by Phoebus - has been promised to him. Now there is also the fact that he is loved by Alfirena (now not so secretly). The chaos of the commercials increases even further because he realizes that the nymph Lycoris has also fallen in love with him. So one can understand Florindo's desperation when he mourns Daphne and at the same time thinks about the possibilities of his second choice.

Galathea sees from afar how Lycoris walks with the clothes of Daphne into the forest towards the mountains. She wonders with Phoebus what this is all about. Phoebus is hopeful of winning Daphne and wants to go find her right away.

Third act

Damon, alone in the thick forest, is desperate because he doesn't know what will become of his silent love for Lycoris. He goes deeper into the thicket.

Florindo also wanders around alone in the forest. He tries to find something but doesn't know exactly what. Lycoris, whom Damon saw in the thicket, appears in Daphne's clothes. Florindo says that Daphne wants to follow Damon and feels betrayed by her. Lycoris does everything to prevent him from seeing her face and wipes his sweat off with the Daphnes handkerchief. Florindo is bursting with anger, curiosity and ignorance. Damon, jumping out of the cave, wants to take the handkerchief, but Florindo snatches it from him. Lycoris escaped. Damon can report that Daphne ordered him to the cave, but none of them know for sure who the escaped is. A conversation with Lycoris doesn't help Florindo either. However, it indicates unfaithful behavior on the part of Daphne.

Lycoris tells Florindo that Daphne is unfaithful to him and incites him to take revenge. But he refuses, because all the guilt lies with Cupid. Alfirena, who joins them, complains to Florindo about his misfortune and brings about the news that Phoebus stole Daphne and disappeared with her in the forest. Florindo now wants to know the whole truth. He tells everyone to go with him to Phoebus' temple.

In Phoebus' temple Daphne tries to break away from Phoebus again. But he holds her tight and reminds her that she herself once wished to visit this place. Now that she is here, she doesn't want him anymore. He threatens her with death if she persists. But Daphne remains steadfast.

Florindo complains and asks whether the temple should now also become a murder pit. Phoebus disapproves of this serious accusation because he - so he believes - never damaged the bond of loyalty between him and Daphne. Therefore, Florindo now accuses Daphne of falsehood (which Damon also confirms) because she, too, made him hope for love. Phoebus calls now to condemn Daphne in the desert. Daphne feels (rightly) innocent and is appalled by it.

Galathea appears, asks skilful questions, and thus proves how misleading and twisted words have become lies. She can explain that Daphne's clothes were stolen. Florindo, even more Damon, even more Phoebus and most of all Lycoris look stupid and immoral. Daphne is proven innocent. Each now asks the other why he, as a supposed schemer, behaved so stupidly. The choir of shepherds and nymphs is looking for balance and does not blame the people involved, but Cupid.

The appearing Cupid warns not to further irritate Cupid's anger. Rather, one should, especially Daphne, use more strength to analyze the arrowheads of love better and to take one's own responsibility more seriously. Then Daphne would not have had this change of heart either. The sense leads to words, the words become deeds: This is how the person concerned determines the direction. Phoebus, glad that Cupid thinks so wisely and finds such conciliatory words, gives Florindo Alfirena, which is supposed to replace him for the loss of Daphne. Damon is assigned to Lycoris and Daphne is transformed into a laurel tree, which from now on is protected from all pests by the great Jupiter. Alfirena and Florindo on the one hand and Lycoris and Damon on the other hand congratulate each other on the good outcome.

music

The scores of both operas are lost. One can assume that Handel had left his autographs behind in Hamburg, as there was evidently the hope that they would still be performed there. But they were probably not in good hands there. Since his stay in Italy, Handel himself had an excellent reference library of his own works, so that these scores, had he ever taken a copy with him, would probably have been preserved in this way. However, the statement of the singer Johann Konrad Dreyer, who after Keiser's departure (September 1706) was co-lessor of the opera house and thus responsible for its continued operation, does not cast a good light on the difficulties of restarting work at the opera house:

“As the beginning of the opera performance should be made, all the scores were hidden. So I first took Solomon after Nebucadnezzar , and looked for the score of them from the individual parts. As soon as the owners of the complete scores saw this, some others gradually came to light. "

Only in the “ Newman Flower Collection” of the Manchester Central Library and in the Aylesford Collection of the British Library could remains of the two operas handed down by David RB Kimbell, Winton Dean and Bernd Baselt be found.

The five-movement instrumental pieces in the “Newman Flower Collection” reproduce neither vocal parts nor text beginnings. But they are marked “Florindo del Sigr. GF Trade ". However, it can no longer be determined with certainty which texts of the two librettos fit the traditional melodies. In terms of rhythm, text distribution and declamation, several aria texts can be considered.

The twelve instrumental movements (HWV 352–354) in the Aylesford Collection (which Charles Jennens had made) are probably also fragments of the two lost operas. They were introduced around 1728 by Handel's junior secretary, the harpsichordist Johann Christoph Schmidt jun. and copied to an anthology by an anonymous scribe. These dances form three simple, key-matching suites, each consisting of four movements. We know from the textbooks that have survived that the proportion of ballet movements in both operas was relatively large. So it is obvious that these suites are probably a combination of choir and ballet movements from both operas.

It is also likely that the Overture in B flat major (HWV 336) which Handel for Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno wanted to use and that of Arcangelo Corelli was rejected "too French" as originally the overture to The delighted Florindo was . Thus 18 musical numbers (even if not completely) from both operas would have been preserved.

Success & Criticism

Handel's friend, sponsor and rival in Hamburg, Johann Mattheson , singer, composer, impresario and music scholar, wrote about the double opera:

"In 1708 [1706!] He made both the Florindo and the Daphne, which, however, did not want to get to Almira."

literature

- Winton Dean , John Merrill Knapp : Handel's Operas 1704–1726. The Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2009, ISBN 978-1-84383-525-7 . (English)

- Bernd Baselt : Thematic-systematic directory. Instrumental music, pasticci and fragments. In: Walter Eisen (ed.): Handel manual. Volume 3. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1986, ISBN 3-7618-0716-3 .

- Bernd Baselt: Thematic-systematic directory. Stage works. In: Walter Eisen (ed.): Handel manual. Volume 1. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1978, ISBN 3-7618-0610-8 .

- Arnold Jacobshagen (ed.), Panja Mücke: The Handel Handbook in 6 volumes. Handel's operas. Volume 2. Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2009, ISBN 978-3-89007-686-7 .

- Albert Scheibler: All 53 stage works by Georg Friedrich Handel, opera guide. Edition Cologne, Lohmar / Rheinland 1995, ISBN 3-928010-05-0 .

Web links

- Libretto for The Transformed Daphne

- .html # HWV4 Further information on Die verandelte Daphne

- Daphne at Ovid (German)

Individual references & footnotes

- ↑ Störtebecker and Jödge Michaels First Part and Störtebecker and Jödge Michaels Zweyter Part (Libretto: Hotter)

- ↑ Circe, or Des Ulysses first part and Penelope and Ulysses other part (Libretto: Friedrich Christian Bressand )

- ↑ Die dying Eurydice, or Orpheus First Part and Orpheus Ander Theil (libretto also by Bressand)

- ^ Winton Dean, John Merrill Knapp: Handel's Operas 1704–1726. The Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2009, ISBN 978-1-84383-525-7 , p. 72.

- ↑ a b c Panja Mücke: Florindo / Daphne. In: Hans Joachim Marx (ed.): The Handel Handbook in 6 volumes: The Handel Lexicon , (Volume 6), Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2011, ISBN 978-3-89007-552-5 , p. 277.

- ^ Bernd Baselt: Thematic-systematic directory. Stage works. In: Walter Eisen (Hrsg.): Handel manual: Volume 1. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1978, ISBN 3-7618-0610-8 , p. 63.

- ↑ Preface to the libretto. , Hamburg 1708.

- ^ The whiteness triumphant over love, or Salomon Opera by Christian Friedrich Hunold [Menantes], music by Reinhard Keizer and Johann Caspar Schürmann (premier 1703)

- ↑ Nebucadnezzar, who was overthrown and raised again, was King of Babylon under the great prophet Daniel Opera by Christian Friedrich Hunold [Menantes], music by Reinhard Keizer (UA 1704)

- ^ Johann Mattheson: Basis of an honor gate. Hamburg 1740, p. 55. (Reproduction true to the original: Kommissionsverlag Leo Liepmannssohn , Berlin 1910)

- ^ Bernd Baselt: Thematic-systematic directory. Instrumental music, pasticci and fragments. In: Walter Eisen (Ed.): Handel manual: Volume 3. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1986, ISBN 3-7618-0716-3 , p. 125 f.

- ^ Winton Dean, John Merrill Knapp: Handel's Operas 1704–1726. The Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2009, ISBN 978-1-84383-525-7 , p. 76.

- ↑ Mattheson, Johann : Basis of an honor gate. Hamburg 1740, p. 95. (Reproduction true to the original: Kommissionsverlag Leo Liepmannssohn, Berlin 1910)